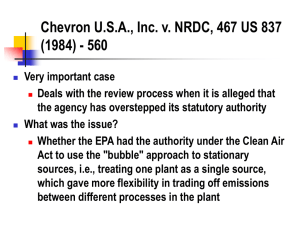

Legislation & Regulation: Statutory Interpretation & Agency Law

advertisement