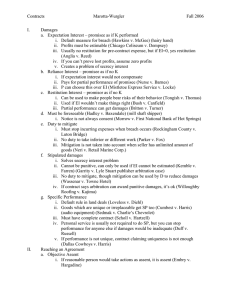

CONTRACT LAW - SWAINE 2019 TABLE OF CONTENT 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. What Law governs? Is there an Agreement? a. Offer 1. Specific offeree 2. Reasonably certainty & definite terms 3. Intent to be bound o Termination of an offer b. Acceptance 1. Bilateral 2. Unilateral 3. Silence c. Consideration 1. Benefit/Detrimental Test 2. Bargained-for Exchange o Invalid Consideration o Consideration Substituted Theories i. Promissory Estoppel ii. Promissory Restitution iii. Non-Promissory Restitution Defenses to Contract Formation a. Statute of Fraud b. Capacity and Fairness 1) Duress 2) Undue Influence 3) Misrepresentation ▪ Fraud in inducement ▪ Fraud in execution ▪ Nondisclosure / Fraud in concealment 4) Unconscionability c. Mistake 1) Unilateral 2) Bilateral d. Charged circumstances 1) Impossibility 2) Impracticability 3) Frustration of Purpose 4) Modification Terms a. Express Terms o Gap Filler o Parol Evidence b. Implied Terms i. Agreement to Agree ii. Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing iii. Different/additional terms Is there a Breach? a. Express Condition b. Construction Condition Damages a. Expectation Damages b. Reliance Damages c. Restitution d. Specific performance 2 2 2 4 8 9 11 13 15 16 18 23 25 28 28 31 35 38 2 CONTRACT LAW 1. WHAT LAW GOVERNS? - Contract is an agreement that is legally enforceable between two or more person • Basis: common law (relying on precedent made by judges, which may be rely on, reverse or differentiate) ▪ Ex: services, employment, construction • Statutes (UCC) applies to sales of goods (movable items), except for Louisiana ▪ Ex: buying/selling chickens, any form of commercial goods ▪ There are also mixed contracts • International plane (ICSG) when businesses involved are by different countries 2. IS THERE AN AGREEMENT? - Is there a contract? Yes, skip to 4. Terms. a. OFFER - Create a power of acceptance in the offeree (Rest. 24) ▪ If the offeror did not intend to conclude the bargain, it is only preliminary negotiations (Rest. 26) 1. Specific offeree - Ads is typically not an offer - only invitation to deal (Rest. 26 - comment b) (Lonergan v. Scolnick finding that communications using “form letter” and delay in response when time is of essence is only preliminary negotiations, and hence did not qualify as a contract) Form Letter - Do not address clearly to the offeree alone using general language - Posted on newspaper ▪ Exception: offer of a reward (Sateriele v. R.J. Reynolds - finding that RJR’s reward offer is not invitation to offer but a unilateral contract that consumers can accept by saving C-Notes and redeeming for rewards without any further negotiation because it 1) repeated use of the word “offer,” 2) absence of the disclaim intention to bound, 3) it has full control over the number of acceptances to the controlled quantity of C-Notes it offered) 2. Reasonably certain & definite terms (Rest. 33) ▪ Price ▪ Quantity - Requirement Contract: a buyer promises to buy from a certain seller all of the goods the buyer requires - Output Contract: a seller promises to sell to a certain buyer all of the goods the seller produces ▪ Basis for breach and remedy 3 → Court must be able to ascertain what party’s obligations are and to determine whether those obligations have been performed or breached. 3. Manifest an intent to be bound - Must be distinguished from invitations to begin negotiations - Objective approach (Lucy v. Zehmer - holding that there is an intention to be bound through manifestation of conduct as an objective person standard) (Rest. 19) ▪ Based on manifestation of intention (Rest. 21) ▪ In case of misunderstanding: (Rest. 20) i. No contract when: (neither party is at fault or both parties are equally at fault) 1) Parallel ignorance 2) Parallel awareness ii. Contract operative by one party’s meaning: 1) One party doesn’t know nor has reason to know / one knows or has reason to know - Exception: when two parties mean the same thing, that meaning prevails (regardless of what an observant think - Rest. 201) Letter of Intent - A document outlining an agreement between two parties before the agreement is finalized. ▪ If unambiguous: follow the plain meaning rule ▪ If ambiguous on intention to be bound (Quake v. AA - finding that the letter that Jones sent to Quake is ambiguous - both showing intention to be bound by authorizing work and intention not to be bound by cancellation clause - so must remand to allow the parties to present other evidence of their intent) a) Could be interpreted as binding if it closely resembles a formal contract, of if it infers that the parties intended it to be regarded as such (Rest. 27) (UCC 2-204(3)) b) Factors to determine whether Letter of Intent is enforceable is based on whether the parties intended to be bound when they agreed in principle (Quake v. AA) (Rest. 27 - comment c) 1. Whether the type of agreement involved is one usually put in writing 2. Whether the agreement contains many or few details 3. Whether the agreement involves large or small amount of money 4. Requires formal writing for the full expression of the covenants 5. Whether the negotiations indicate that a formal written document was contemplated at the completion of the negotiations 6. If the negotiation is abandoned, what are the reasons? 7. Extent of assurance previously given by the party which now disclaim any contract 4 8. Other party’s reliance upon the anticipated completed transaction c) Possible interpretation: 1. Intention to be bound when they signed letter of intent 2. No intention to be bound when they signed letter of intent 3. Minority: Bound themselves to negotiate in good faith to attempt to reach agreement on a contract, while also reserving the right to terminate their negotiations if they should be unable to reach agreement. ▪ Afford an opportunity for experts to add to the total agreement protections against various risks as they think necessary ▪ Still morally free to withdraw when it appears that the experts have raised a substantial issue on which they are unable to agree. Termination an offer (any time before acceptance) 1. Lapse of time - When would the duration of the offer run out? a. When time for acceptance is fixed in the offer: start running from the time the offer was received b. When no time of acceptance is fixed: run out after a reasonable time 2. Revocation a. Can he revoke? - Yes unless: i. Option contract (Rest. 63b) - Exception: when there is an option contract, the power of acceptance is not terminated by rejection, or counter-offer, revocation, or death/incapacity (power of acceptance will be held open during the term of the option) (Rest. 37) - To terminate the option contract, the parties would need to make another binding agreement, with new consideration on both sides. ▪ Bilateral o Offer + consideration a. Majority approach: consideration value must be received, not mere recital (Berryman v. Kmoch) - finding that the realtor was not bound to find buyers + since the option contract was not paid, he did not provide consideration to keep an option contract, therefore the offer is revocable at any time. 5 • Nominal consideration: acceptable because this only mini-consideration to keep option open, the actual value of the exchange is not discussed yet b. Minority approach: Rest 87(1)(a) - Formality: mere recital of consideration, in writing and signed is sufficient o Offer + Pre-acceptance substantial reliance a. Based on existence of an offer (Rest. 87(2)) (Drennan) * finding that the General contractor justifiably relied on the bid that the Sub-contractor bid to them to compile their general bid when there is silent on revocation term, unlike James Baird Co. v. Gimbel Bros., and there was no reason to know that SubContractor has made a mistake because there are variation between the bids, therefore PE is an irrevocable contract) MOSTLY FOR CONSTRUCTION-BIDDING CONTRACT → Make an offer irrevocable by creating an option contract ▪ Exception: 1. When Sub-contractor bid had “expressly stated or clearly implied that it was revocable at any time before acceptance” (James Baird v. Gimbel) 2. When General contractor involves in “bid shopping” - trying to find another subcontractor while continuing claiming that the original bidder is bound / “bid shopping” b. Clear assurance that results in a foreseeable negative change in offeree’s position - more than an offer but less than a clear promise (Pop’s Cones) - finding that the Resort’s multiple assurance by saying that it is 95% done, should pack the old location, letter of intent, etc. (Harvey v. Dow) (Rest. 90) ▪ Analyze 4 elements of Promissory Estoppel: 1) Promise ▪ Manifest objective assurance 2) Reasonable Expected Reliance 3) Actual Reliance 6 4) Injustice → Create a Contract ▪ Unilateral: a. Beginning performance makes offer irrevocable by creating option but does not bound the offeree to complete performance (Cook v. Coldwell Banker) (Rest. 45) b. Beginning performance makes offer irrevocable and bound offeree to complete the performance to collect what was promised (Rest. 62) ▪ Protect the offeror in justifiable reliance on the offeree’s implied promise - Preparation is not sufficient, must tendering ▪ Exception: If the preparation constitutes substantial reliance ii. Offer irrevocable by seal (statute) - discussed in Normile. b. Did he revoke? ▪ Offeror acted inconsistent with his intent to make an offer (Rest. 42) ▪ Offeree learned about offeror’s doing through a reliable source (Rest. 43) ▪ Normile v. Miller - buyer offered and seller counter-offer. Buyer did not react to the counter-offer until he heard that the seller had revoked her counter-offer by entering into a contract with another buyer Segal. Court finding that Segal transaction was valid and the Normile was not because a) seller did not enter into an option contract with buyer, b) revoked her counter-offer before buyer can accept c. Did he revoke in time? Mailbox Rule: Acceptance letter is effective upon dispatch. Others are effective when they are received (rejection, revocation) (Rest. 63a) • Exception: - Stated otherwise in contract - Subsequent acceptance letter will be effective when received - Does not apply to option contract: an option contract is accepted when the acceptance letter is received (Rest. 63b) 3. Rejection - Terminate the offer even when the time expiration has not lapsed (Rest. 36) 4. Counter-offer - Does the term vary from offer to acceptance? 7 - An offer by the offeree concerning the same subject matter but different terms than the original offer will terminate the power of acceptance and will create a new offer (Rest. 39) (Rest. 59 - a conditional acceptance based on assent to the additional terms is also a counter-offer) ▪ UNLESS the offeror intended a contrary intention (Rest. 39b) ▪ Normile v. Miller (finding that seller made a counteroffer by returning the original offer with multiple corrections and added new terms) • Inquiry will not terminate the offer (“would you consider lowering your price?”) 5. Death/incapacity (Rest. 48) 8 b. ACCEPTANCE - Revocation, rejection, or acceptance is received when the writing comes into the possession of the person addressed (Rest. 68) - When offer does not specify, can either accept as a returned promise or return performance (Rest. 32) i. Bilateral - Returned promise Different term - Do the terms vary? (from offer to acceptance) - Is contract for sale of goods? ▪ Yes. UCC 2-207 (Battle of the Forms) ▪ No. Mirror Image Rule → offer rejected + power of acceptance terminated ▪ Exception: when there is an option contract (power of acceptance will be held open during the term of the option) ii. Unilateral (Common Law ≠ Restatement) a. Majority approach: Beginning performance makes offer irrevocable by creating option but does not bound the offeree to complete performance (no mutuality of obligation) ▪ Cook v. Coldwell Banker - finding that the employee has made substantial performance in reliance to the offeror’s bonus, which is a substitute for both consideration and acceptance, is an option contract than the employer cannot revoke. (Rest. 45 - does not require substantial performance - simply beginning performing) ▪ Offeree’s performance is both consideration and acceptance of the offer ▪ Rest. 45 - comment e: Only offeror is bound, the offeree is not bound to complete performance a) If there is explicit reservation of power to revoke based on conditions outside of offeror’s control, then Court may not find a breach (Storti v. UWash) b) If it is a condition within offeror’s control, then it is illusory promise (Sateriele v. RJR - finding that if the termination clause applies to ALL catalogs instead of certain (but not all), then the promise is illusory because it gives the offeror an unrestricted power) b. Minority approach: Beginning performance makes offer irrevocable and bound the offeree to complete performance to receive the promise (Rest. 62) iii. Silence (Rest. 69) 9 - General rule: do not constitute acceptance but in some limited circumstances silence may result in the formation of a contract o Exception: 1) If the offeree gives the offeror the impression that silence will be considered an acceptance (previous dealings) 2) When the offeror has told the offeree that silence will constitute acceptance 3) Offeree takes the benefits of offered services when they have reasonable opportunity to reject Electronic and “Layered” Contract 1. Shrinkwrap terms: The purchaser orders a product over telephone, Internet, or store. After removing the wrapping, the purchaser has an opportunity to inspect the product and review the contract terms. There are two scenarios: ▪ If purchaser is dissatisfied with the product/terms: return within a certain number of days. ▪ If does not return within that period, the purchaser agrees to the terms. A. Easterbrook / Rolling approach (UCC 2-204) - there is only one contract from the beginning - Buyers are not bound contractually until they received both the product and the seller’s term of sale, and then decide within reasonable time. - When a buyer places an order, it is NOT YET an offer. The seller, as master of the offer, may invite acceptance by conduct when shipping the product. A buyer may accept by performing the conduct the seller proposes to treat as acceptance. ▪ DeFontes v. Dell, Inc. - finding that although the consumer has three chances to review the T&C: i) hyperlink on website, ii) reading T&C in the invoice, iii) reviewing copy of terms sent along with the packaging - none was conspicuous enough to give rise to a contractual obligation. ▪ Dye v. Tamko Building Products - Tamko invited purchasers to accept its contract terms by opening and retaining the shingles through clear display on exterior wrapping of the package, a reasonable means of acceptance-by-conduct. The home-owners, through their roofer agents, validly accepted those terms. B. Klocek Approach (UCC 2-207) - contract with proposal for additional terms that was not binding unless expressly agreed to by the buyer - The buyer is the offeror, the contract is formed when the seller accepted the payment and promised to ship. - An agreement affixed to the packaging is a proposal for additional terms that was not binding unless expressly agreed to by the buyer. - Any terms proposed by the seller that materially altered the contract would not automatically become part of the contract, even between merchants. 10 → Both parties are bound when the seller accepts payment. Buyer may lose the right to cancel the sale within the time. ▪ Step-Saver Data Systems v. Wyse Technology 2. Clickwrap terms: before completing the purchase of the product, the buyer must click a button labeled “I agree,” “submit” or some equivalent phrase. ▪ Often must scroll through the seller’s term of sale before clicking the agreement button ▪ Cannot complete sale if the buyer refuses to accept 3. Browsewrap terms: transactions involve information made available by Internet providers on their websites. The term on the website states that by using the site the user agrees to the provider’s term of use. ▪ User is not required to scroll through the terms or click any agreement ▪ The user’s agreement to the term is implied from browsing the site → User does not need to clearly assent → Leads to conspicuous issue of whether assent is given or not ▪ Long v. Provide Commerce, Inc. - The hyperlinks and the overall design of the ProFlowers.com web would not have put a reasonably prudent Internet user on notice of Provide’s Term of Use. Plaintiff therefore did not unambiguously assent to the subject arbitration provision simply by placing an order on the website. It is the responsibility of the website owner to put users on notice of the terms they wish to bind consumer. ▪ - Bright Line Rule Because of the nature of the browsewrap term, no affirmative action is required. ▪ The validity of a browsewrap agreement turns on whether the website puts a reasonably prudent user on inquiry notice of the terms of the contract. ▪ Depend on two federal cases (Specht and Nguyen) i. Specht: a consumer’s clicking on a download button does not communicate assent to contractual term IF the offer did not make clear to the consumer that clicking download button would signify assent (based on a reasonably prudent buyer) ii. Nguyen: It is not enough to rely on proximity of the hyperlink to enforce a browsewrap agreement, but must include something to capture the user’s attention and secure her assent (ex: explicit textual notice that using the website is agreeing to the terms) 11 c. CONSIDERATION (Rest. 71 - 90) 1) Benefit/Detrimental (Hammer v. Sidway) - finding that since the nephew refrained from his rights to drink, use tobacco, swearing and playing cards until 21, he suffered from a legal forbearance and therefore constitute consideration. i. Benefit to promisor ii. Detriment to promisee (preferred) - Legal forbearance: the promisee does something he is under no legal obligation to do or refrains from doing something that he has a legal right to do. - Gifts generally are not consideration ▪ Gifts with condition: consider BOTH benefit AND detriment 2) Bargained-for Exchange (Pennsy Supply v. American Ash) (Rest. 71) - finding that Pennsy and American Ash did not need to bargain for the disposal cost as terms of the agreement to be qualified as bargained-for exchange under consideration. - Whether there is mutual inducement: return promise/performance was sought for ▪ o Does not require bargaining (negotiation process) Consideration as Inducing Cause (Rest. 81) ▪ Having mixed motives does not prevent it from being valid consideration ▪ When the promise from promisor does not induce a return performance/promise, the returned performance/promise can still be consideration on its own (creating a unilateral contract) o Modification (Common Law ≠ UCC) a. Common Law: a contract modification is unenforceable if there is no new consideration (modifying extra tasks) b. UCC 2-209: contracts modifications sought in good faith are binding without consideration Invalid consideration a. Sham consideration (Dougherty v. Salt) - finding that the aunt writing down “value received” for a conditional gift to the 8-year-old boy is still not consideration. b. Past performance / Preexisting Legal Duty (Rest. 73) (Plowman v. Indian Refining Co finding that the payment made to laid off employees was conditional gifts from gratuity because there was no consideration for past performance. Travelling to pick up the check is not consideration because it was a condition to obtain the gift) ▪ Exception: A similar performance is consideration IF modified (differs from what was required) ▪ Travelling to receive the gift is only condition to a gift/conditional gift (Tramp example) 12 c. Inadequacy (Dorhmann v. Swaney) - finding that the exchange of a middle name to obtain the properties of $4 million is grossly inadequate. ▪ General rule: if the requirement of consideration is met, there is no additional requirement for: (Rest. 79) 1) Benefit/Detrimental test 2) Equivalence in value exchanged ▪ Exception: unless the amount is so grossly inadequate that it shocks the conscience (comment (e)) ▪ Gross inadequacy + other factors (duress, undue influence, etc.) is an indicator that it is a sham consideration 3) Mutual obligation Distinguish: Nominal consideration (Common law ≠ Restatement) a. Common law Majority approach: will make an option contract if the option is in writing and proposes fair terms (Berryman v. Kmoch) and must be paid. b. Restatement Minority approach: recital is sufficient whether the nominal consideration is in fact paid is irrelevant (Rest. 87(1)). d. Illusory promise (Marshall Durbin v. Baker) (Rest. 77) ▪ The presence of an illusory promise does not destroy the possibility of a contract. Instead, it may create the illusory promise that can be accepted by performance to form a unilateral contract. ▪ No consideration if promisor has an alternative choice (entirely optional) ▪ Exception: 1) Requirements and Output Contract 2) Conditional Promises: if the condition is no entirely within the promisor’s control 3) Right to cancel/withdraw 4) Every alternative choice involves legal detrimental or not within promisor’s control 13 CONSIDERATION SUBSTITUTE A. Promissory Estoppel / Detrimental Reliance (Rest. 90) - Create a contract. - Q: Whether D made a promise to P on which P acted to his detriment? 1. Promise - A promise can be based on express promise as well as conduct. ▪ General promise can be supported by conduct to “gap filler” definite terms (time, location) (Harvey v. Dow) - finding that there is sufficient evidence for a promise because her brother voluntarily helped her build the house and get the permit for her house and father told her he would execute a deed to her for the property even though there is no express promise because he has objective manifested his intent to confirm his general promise to convey land to Teresa. - A promise must happen before the change in position was announced/take place (the promise needs to induce the detrimental reliance) (Hayes v. Plantations Steel) 2. Reasonable Expected Reliance ▪ “Going above and beyond” duty may disqualify expected reliance (King v. BU) finding that indexing is extreme for the scrupulous care that King required for the bailor - bailee relationship, and thus maybe beyond reasonable expected reliance. ▪ Ex: Promise/Assurance may induce expected reliance (Aceves v. US Bank) - finding that the Bank’s assurance to “work with her on a mortgage reinstatement and loan modification” induced her to forego the ability to switch from a Chapter 7 bankruptcy to a chapter 13, which may allow her to keep her estate. It is also reasonably relied on because US Bank reasonably expected her to so rely and it was foreseeable that she would do so. 3. Actual Reliance - Does the reliance need to be detriment? - Detriment scale: i. Promisee worse off than if promise was not made ii. Any change if initially detrimental (seem like sacrifice) iii. Any change if that action would not have been made but for the promise (Katz v. Danny Dare) (Aceves v. US Bank) iv. Any change in position is enough 4. Injustice - The presumptive remedy is to give P what they gave up - Who gains what? Is it unfair? 14 Is it a charitable subscription or marriage settlement? (Common Law ≠ Restatement) a. Majority approach (Common Law: King v. BU): D still need to supply consideration, either under Contract or Reliance theory b. Minority approach (Rest. 90b): do not need to supply consideration B. Restitution I. Promissory Restitution - General rule: A promise based on moral obligation without legal consideration is only valid to cases where at some time or other valid consideration existed. ▪ (Mills v. Wyman) - finding that since the promise of reimbursing for the medication that P bought to take care of his son is invalid because the father does not earn benefit from it. - Exceptions: A promise is made enforceable when: 1) Action is on a renewed promise when Statute of Limitations run out (Rest. 82) 2) Promise to perform a voidable obligation (Rest. 85) 3) Promise to pay a debt discharged by bankruptcy (Rest. 83) 4) Material benefit rule: (Webb v. McGowin) - finding that when P diverted the block and saved D from serious bodily harm, even without D’s request, he has conferred a material benefit (receiving safety in exchange for monthly payment for the P, who was seriously injured and could not work as consideration). (Rest. 86) 1. Material benefit conceived by Promisee ▪ Example: Emergency services and necessaries (comment d) 2. A promise is made in recognition of the benefit received • In Emergency case, essentially back-date promise to just before the act • Is the promise invalid? (comment f) i. Act was a gift ii. Act was a preexisting duty iii. Promisor himself has not been enriched iv. Given back value is disproportionate to the benefit 3. Binding to the extent necessary to prevent injustice II. Non-Promissory Restitution a. Is there unjust benefit? 1. Benefit received 15 2. D has knowledge of that benefit 3. D has accepted or retained the benefit 4. It would be inequitable for D to retain the benefit without paying fair value for it based on circumstances ▪ Has there been exhaustion of remedies? (Commerce Partnership 8098 v. Equity) - finding that the Subcontractor can only recover restitution from the owner when the Sub has exhausted remedies against the general contractor + the owner has not paid the general contractor for the work performed. ▪ - Yes: Go to b) Did P acted officiously? - No: NPR inapplicable. Pursue alternative remedy Has the restitution been paid? b. Did P act officiously? ▪ Yes: Go to c) Is it an Emergency? ▪ No: Can claim recovery for unjustly enrichment under restitution (Rest. 1,2 of Restitution) c. Is it an Emergency? (Section 116 of Restatement of Restitution) • P acted officiously with an intent to charge (Professional competent service) Section 20 of Restatement of Restitution: limit restitution recovery to protect the health of others to providers of “professional services” - unless Emergency • The service was necessary to prevent bodily harm • P has no reason to know the other would not consent to receiving them, if mentally competent • D cannot give consent (mental impairment/extreme youth) (Credit Bureau Enterprise v. Pelo) - finding that charging for the medical service provided to a bipolar patient is justified because the patient cannot give out valid dissent, therefore can claim recovery for unjustly enrichment) • Yes: NPR inapplicable • No: P can claim NPR 16 3. DEFENSES A. STATUTE OF FRAUD (Rest. 129 - 139) Severability (Crabtree v. Elizabeth Arden Sales Corp) - finding that the signed portion contained parties, position that the employee will take place, salary, the duration of employment is validly supplied by an unsigned memo that said, “two years to make good.” - Multiple documents taken together through oral testimony may constitute a signed writing sufficient to fulfill the statute of frauds if all documents refer to the same subject matter or transaction, and at least one is signed by the party to the charged with the contractual obligations. (Rest. 132) ▪ CAUTION: Memo can be submitted even if it is not directly related to the contract, or if it repudiates or cancels the contract, or assert that it is not binding because it was not in writing (Rest. 133) - Two elements: 1) A contractual relationship between the parties 2) The unsigned writing must “refer to the same transaction as that set forth in the one that was signed” ▪ Both Restatement and UCC take a lenient view of what may constitute a “signature” (may be a symbol made or adopted with an intention, actual or apparent, to authenticate the writing) (Rest. 134) CONTRACTS “WITHIN” STATUTE OF FRAUDS - These contracts are unenforceable unless there is a written memorandum or an applicable exception: 1. Marriage contracts ▪ Provide consideration by marrying the other party 2. Over one-Year contract: A contract that must be performed longer than one year (the one-year provision) (Rest. 130) ▪ Refers to performance fully within one year, NOT termination within one year ▪ Contracts of no duration are not within the statute of frauds ▪ A contract that states it cannot be performed in less than one year is within the statute if it is by express term - As between Statute of Frauds and Promissory Estoppel, PE would prevail (Rest. 139) ▪ Alaska Dem Party v. Rice ▪ Factors to determine whether enforcement of the promise is valid for injustice to be avoided: (Rest. 139(2)) 1. The availability and adequacy of other remedies (cancellation or restitution) ▪ When P has rendered partial performance to an unenforceable contract because of Statute of Fraud, Court will ordinarily grant P a 17 remedy in restitution for the reasonable value of that partial performance. 2. The definite and substantial character of the action or forbearance in relation to the remedy sought 3. The extent to which the action or forbearance corroborates evidence of making and terms of the promise, or the making and terms are otherwise established by clear and convincing evidence 4. The reasonableness of the action or forbearance 5. The extent to which the action or forbearance was foreseeable by the promisor 3. Land Contract: A contract for the sale of an interest in land (Common law ≠ Restatement) ▪ Other interest, not necessarily sale, such as easement, mortgage, leases ▪ Beaver v. Brumlow (finding that when D has substantially performed on the oral agreement to improve the land, cashed in 401-K retirement plans, and total of $85K investment into the land, which objectively manifest the reliance that an outsider reasonably conclude that the contract exists, even though Land contract should be in writing, is sufficient to grant specific performance. ▪ Common law: Unequivocal referable test - Two factors that Court looked for: 1) taking possession of the land 2) making valuable, permanent, and substantial improvements to the property ▪ Doctrine of specific performance (Rest. 129): the promisee is in reasonably reliance on promisor’s continuing assent and has changed position so that injustice can be avoided only by specific performance. 4. Executor – administrator contracts: A contract of an executor or administrator to answer for a duty of his decedent 5. Sale of Goods contracts $500+. Exceptions: i. Contracts for the sale of specially manufactured goods for $500+ (when performance begun) ii. Non-injured party admits that contract was made iii. Payment has been accepted goods have already been received 6. Suretyship: A contract to answer for the duty of another ▪ Narrowed down by common law to only between the creditor and debtor ▪ Exception: the promisor’s main purpose is to further the promisor’s own economic advantage (main purpose rule) ▪ Inapplicable when the promisor who has guaranteed payment of another’s debt did so for his economic advantage, rather than out of solicitude for the debtor’s well-being. 18 B. CAPACITY AND FAIRNESS (Rest. 161 - 177) - What is the contract at hand? - What is the relationship? - What is one party trying to get out from? - What is the effect on the contract? 1. Duress (Rest. 175(1)): voidable contract (will be binding unless disaffirmed and may be expressly or implicitly ratified by the victim) - (Totem Marine Tug v. Alyeska Pipeline) - finding that Alyeska committed duress because they intentionally forced Totem to accept $97K instead of the total of $260K invoice AND sign the release as Totem’s only option to avoid bankruptcy. 1) Improper wrongful/coercive acts/threat by the other party (Rest. 167) ▪ Crime, tort ▪ Breach of duty of good faith and fair dealing ▪ Resulting in unfair terms / would harm the recipient ▪ Use of people for illegitimate ends ▪ Example: refusing to honor the existing contract / a threat to breach the contract or to withhold payment of an admitted debt (Alaska Packers Association v. Domenico) 2) Inducing involuntary assent - Whether the threat induces the assent. 3) Circumstances permitting no alternative (Rest. 175 - comment b) ▪ Example of alternatives: availability of legal action, alternative sources of goods, services, or funds, or toleration if the threat is minor. ▪ Economic duress a) Majority: if the duress is not caused by defendant party but because of the injured party’s own economic trouble, then court is sometimes reluctant to review the contract (there must be a causal link between coercive acts and circumstances of economic duress) b) Minority: It is enough that one party takes advantage of the other side’s dire circumstances without having caused the financial hardship. ▪ An available alternative or remedy may not be adequate where the delay involved in pursuing that remedy would cause immediate and irreparable loss to one’s economic or business interest 19 2. Undue Influence (Rest. 177) (Odorizzi v. Bloomfield School District) - finding that there is undue influences because the discussion happened at his apartment, right after he was released from arrest, refusing for him to meet with lawyers, under threat of publication that will bring him humiliation, while he was under such severe mental and emotional strain. 1) Unfair persuasion [“excessive pressure”] - Changes the way the person would ordinarily decide (vulnerable state of mind) ▪ Discussion at unusual or inappropriate time ▪ Consummation in unusual place ▪ Demand that business be finished at once ▪ Extreme emphasis on consequences of delay ▪ Use of multiple persuaders by dominant side against single servient party ▪ Absence of third-party advisers to servient party ▪ Statement that no time to consult financial advisers or attorneys 2) Domination; OR 3) Confidential/special relationship ▪ Is the party vulnerable? (contextually or in relation to the other party) ▪ Victim depending on the idea that the other party is looking for their best interest 3. Misrepresentation / Fraud in Inducement (Rest. 164) (Syester v. Banta) - finding that the invitation to buy dance lesson was a misrepresentation because the dance studio intentionally made wrong statements and promised that she could be a professional dancer and awarded Gold Star course + the victim justifiable relies on this because the studio possesses skills and judgment in dancing. - Contract integration through disclaimer or merger clause does not bar the buyer’s action to rescind the contract on the basis of fraud 1) Fraudulent OR material in character (Rest. 162) a. Fraudulent: consciously/intentionally made falsely b. Material in character: if the assertation will probably induce a reasonable person to agree 2) Justifiable reliance i. State of opinion - Usually opinions that concerns quality, value, authenticity are not misrepresentation when it expresses a belief, without certainty, as to the existence of the facts. (Rest. 168) o Exceptions (Rest. 169) ▪ Opinioner does not honestly believe it 20 ▪ The Opinioner knew of facts that contradict his statements ▪ When relying is justified because of confidential relationship ▪ Reasonable belief in special skills or judgment ▪ Opinee is particular susceptible to a misrepresentation of that type 3) That induces recipient’s assent ▪ Counter-argument: showing that the victim was not induced or that she is not susceptible to the misrepresentation - Result: Contract voidable Fraud in inducement v. Fraud in execution a. Fraud in inducement - Occurs when the victim intended to make the contract but was told a false statement regarding the terms or obligations of the transaction - The party knows what he is signing but does so as the result of misrepresentation - Make a contract voidable b. Fraud in execution (Rest. 163) - Occurs when the victim was tricked into signing a contract under circumstances in which the nature of the writing could not be understood - The party is deceived as to the nature of the writing - Make a contract void 4. Fraud in execution (Park 100 Investors v. Kartes) (Rest. 163) - finding that there is fraud in execution because Park 100 induced the Kartes to sign a personal guaranty of lease, which they did not want to, by concealing it as “Lease Agreement” and did not correct the Kartes when he had a chance to. Although parties have a duty to read, but this is alleviated when the other party commits fraud. 1) Fraud or Material misrepresentation i. Fraud: actively/intentionally make statements not in accord with facts or has reason to know the basis to induce assent ii. Material misrepresentation: failure to disclose a material fact that a reasonable person would want to know to induce assent 2) Justifiable Reliance ▪ Special relationship ▪ Duty to disclose even when there is no special relationship: i. When necessary to correct a prior assertation 21 ii. Correct an effect of a writing 3) That induces recipient’s assent - Can introduce Parol evidence to show an “excusable ignorance of the written terms which may be proven by presenting evidence that someone secretly changed an important term of the contract before the ignorant party signed it, and that the ignorant party lacked a reasonable opportunity to learn of the change before signing.” - Results: Contract voided 5. Nondisclosure / Fraudulent concealment (Rest. 161) (Hill v. Jones) - finding that even when there is an integration/ “as-is” clause, parol evidence is always allowed to show fraud. Here, the seller failed to disclose a material fact of termite history that could change the buyer’s decision. Although the buyer has a duty to ask, this duty is alleviated when the seller knows/should have known because they have more information) 1) Is there a nondisclosure? 2) Is the nondisclosure of material fact or fraudulent in nature? a. Fraud: actively/intentionally conceal to induce assent b. Material misrepresentation: failure to disclose a material fact that a reasonable person would want to know ▪ Exception: when the information is too expensive to acquire, then there is less duty to know and inform ▪ There is obligation to disclose non-material facts if the buyer asks ▪ Failure to use reasonable care (duty to read, duty to ask) may be bad for injured party 3) Justifiable Reliance ▪ Fiduciary or trust/confidence relationship: the term of the contract must be fair and must be fully explained to the other party. If the terms are not fair, beneficiaries can void the contract (Rest. 173) (Rest. 161(d)) ▪ In the absence of relationship, where a material fact is known to one party by virtue of his special position and could not be readily determined by the other, the know party must disclose ▪ ▪ Example: seller v. buyer of a house Nondisclosure or concealment would amount to a breach of good faith (Rest. 161(b)) 1) Difference in intelligences of the parties / relationship 2) Manner in which information was acquired 3) Fact was not readily discoverable or not 22 4) Is the buyer or seller fail to disclose? 5) Type of contract 6) Importance of the fact not disclosed 7) Active concealment 4) That induces recipient’s assent - Results: Contract voidable because there was no manifestation of assent (Rest. 163) 6. Unconscionability (Rest. 208) (Williams v. Walker-Thomas Furniture - finding that the store was 1) using adhesion contract to force the consumer to buy (who has less bargaining power) while aware of their financial position, into signing for an unfair contract that 2) unreasonably favor the store, such as the ability to repossess all items) (Higgins v. Superior Court) - finding that the Agreement and Release drafted by the television defendants, 1) having 24 single spaced pages that has even small font for Release page and no clear signal of Arbitration clause, with complex legal terms, with the instruction of flipping through the pages and sign the initials within 10 minutes, 2) that bounds only the Higgins to arbitration clause is unconscionable.) - Evaluate at the time the contract is made - Court can either: a. Void the contract b. Enforce the remainder of the contract without the unconscionable term c. Limit the application of the unconscionable term to avoid any unconscionable result ➢ Two-prong test - Sliding scale: the more substantively oppressive in the contract term, the less evidence of procedural unconscionability is required to come to the conclusion that the term is unenforceable, and vice versa i. Procedural unconscionability (absence of meaningful choice) - quasi-fraud or duress - Focuses on factors of surprise and oppression, with surprise being a function of the disappointed reasonable expectations of the weaker party a) Party’s knowledge b) Reasonable opportunity to understand the terms of the contract ▪ Are the terms inconspicuous or incomprehensible? ▪ “Take it or leave it” in nature? c) Were important terms hidden? d) Bargaining power ▪ Even if given consent (meaningful choice), it is immaterial (ex: financial status, educational background, work experience) 23 ▪ Some court will conclude that adhesion contract satisfies procedural unconscionability, but not in Higgins court (only an indication of procedural unconscionability) ii. Substantive unconscionability (terms unreasonably favor one party) ▪ Overly harsh or one-sided results ▪ Lack of “bilateral” application ▪ Legal question to be resolved by the Court C. MISTAKE 1. Unilateral (Rest. 153, 154) (BMW Financial Services. V. Deloach) - finding that BMW should bear the mistake because although it is not “neglection of a legal duty,” it was reasonably concluded that but for its failure to flag that the case is in litigation to the agency + waited nearly a month to inform Deloach of the mistake, there would have been no mistake. This change in amount also upsets the expectation of the parties, breaching the promise to act in good faith and fair dealing. The amount that BMW got back was not unconscionable or overly harsh outcome to BMW. - An error concerning a basic assumption on which the contract was made, that is made by only one of the parties to a contract. - Factors: 1) A unilateral mistake 2) About “basic assumption” of contract ▪ Is the mistaken fact the primary reason that the parties entered into the agreement in the first place? ▪ Basic assumption: affecting the core and material terms → Rescission available ▪ Collateral mistake: affecting the peripheral → cannot rescind 3) “Material adverse effect” on mistaken party? ▪ Make it more valuable for one party and less on the other 4) The mistaken party does not bear the risk (Rest. 154). a) Risk allocated by agreement; b) Party was aware of limited knowledge, but went ahead; c) Court assign risk to that party 5) Enforcement would be unconscionable OR non-mistaken party had reason to know of other’s mistake (palpability - the mistake is so obvious that the non-mistaken party should have realized) a. Nature of P’s mistake 24 ▪ Is it a mechanical error (mistakes in calculation) or mistakes in judgment as to the value of an object? ▪ Is it a failure to act in good faith? fraud, cheating, OR disappointing the expectation of other party (Rest. 157) ▪ If unconscionability: analyze procedural and substantive b. The delay in discovering the mistake c. D’s reasonable reliance on the mistake ▪ Did the non-mistaken party suffer any loss? d. Forfeiture of the mistaken party ▪ What is the impact of the mistake on the mistaken party? → If yes to 5): Grant rescission → If no to 5): Deny rescission and enforce contract as is. 2. Mutual mistake (Rest. 152, 154) (Lenawee County Board of Health v. Messerly) - finding that when both parties are unaware of the septic tank, that made the whole house inhabitable, and there is an As-Is Merger Clause (“Purchaser has examined this property and agrees to accept same in its present condition. There are no other or additional written or oral understanding”), then the burden to bear this risk is assumed by the buyer when they signed for the house. 1) A mutual mistake? - Both parties erroneously assume about a fact that turn out not to be true 2) About “basic assumption” of contract? ▪ Basic assumption: affecting the core and material terms → Rescission available ▪ Collateral mistake: affecting the peripheral → cannot rescind 3) “Material effect” on exchange of performance? ▪ Make it more valuable for one party and less on the other → Voidable by the adversely affected party UNLESS he bears the risk of the mistake ▪ Clerical errors: When the mutual mistake consists of the failure of the written contract to state accurately the actual agreement of the parties, reformation of the contract to express the parties’ mutual intent is the normal remedy. ▪ Mutual mistake: The court can act on discretion to determine which blameless party should assume the loss resulting from the mistake they share (Res. 154(a)) 4) The adversely affected party does not bear the risk - Party might bear risk because: 25 a. Risk allocated by agreement; ▪ Example: As-is Merger clause b. Party was aware of limited knowledge, but went ahead; ▪ Seller’s knowledge ▪ Conscious ignorance: if seller realize that something is off but rather not know and do not want to further the problem (Hill v. Jones) c. Court assign risk to that party ▪ A party failing to perform its legal duty ▪ The mistake was the result of his failure to act in good faith and in accordance with reasonable standards of fair dealing D. CHANGED CIRCUMSTANCES 1. Impossibility (Rest. 162 - 164) - Require for “objective impossibility” - the thing promised could not be performed at all ▪ Rest. 262. Death or incapacity of person necessary for performance ▪ Rest. 263. Destruction, deterioration or failure to come into existence of things necessary for performance. 2. Impracticability (ability to carry out the performance) (Rest. 261) - Extreme increase in the cost of extraction justified D’s nonperformance (it is very difficult to convince Court to excuse contract based on significant increase in cost of performance) - Make it sufficiently different from what the parties had both contemplated at the time of the contract as to be “impracticable” ▪ (Hemlock v. Solarworld) - finding that there is NO impracticability because market changes, regardless of whether the actual reason is illegal or not, is an anticipated reason for the set price in the beginning. Release / “Force majeure” clause: provide for excuse where performance is prevented or delayed by circumstances “beyond the control” of the party seeking excuse. Superior Risk Bearer (Economic Theory - Posner): in the absence of a contractual provision, the risk should be assigned to the party who is in the best position to prevent the event from occurring, to minimizes its consequences at the lowest cost. 3. Frustration of Purpose (value of the performance) (Res. 265) - The value of the OTHER’s performance is now meaningless because of a supervening change in extrinsic circumstances. ➢ ROADMAP 1. Unexpected (foreseeability) and important event (upsetting “basic assumption”)? 26 ▪ Mutual profitability/economic distress/continuation of existing market condition is not a basic assumption ▪ ▪ Unless the change is too drastic that would drive a company to bankruptcy Drastic changes in the market nor illegality of the intervening cause is basic assumption ▪ 2. Yes: proceed to (2) Was event fault of party seeking relief? (Rest. 266) ▪ No, proceed (3) 3. The party seeking relief bears the risk of that event’s occurrence (in contract or circumstances)? ▪ 4. No, proceed (4) Then: a. Did event make that party’s performance impracticable -- substantially more difficult or expensive? (If yes, performance excused for impracticability.) b. Did event substantially destroy value of other party’s performance? (If yes, performance excused for frustration.) (Mel Frank Tool v. Di-Chem Co.) - finding that there is no frustration of purpose because Di-Chem can still use the storage for storing non-hazardous chemicals even when the City ordinances forbid the storage of hazardous chemicals at this site. ▪ Need to completely destroy the value of performance to be excused E. MODIFICATION - For a new contract to be enforceable, there must be new consideration 1) Is there any change (small or modest addition to/alternation of performance is enough) to the original bargained-for exchange consideration? o Yes: There is new consideration o No: Invalid consideration. Go to 2) Exception. ▪ Go to Invalid Consideration ▪ A contract that obligates a party to perform what he or she has a prior existing duty to perform under an earlier agreement is not enforceable for lack of consideration (Alaska Packers Association v. Domenico - finding that modification to the contract to pay the fishermen $100 instead of $60 as agreed lacks new consideration because the fishermen did not have to do anything more than what they were supposed to do under the original contract where they should be doing whatever the captain requires) (Rest. 73. Performance of Legal Duty) 2) Is there any exception to the modification without new consideration? 27 ▪ Exception for Modification: 1. Unforeseen circumstances (Rest. 89(a)) - a promise of modification is binding if “fair and equitable in view of circumstances not anticipated by the parties when the contract was made.” ▪ May be applicable even if the unforeseen circumstances would not fully qualify for excuse based on the impracticability doctrine (just more expensive, taking longer) 2. Reliance (Rest. 89(c)) on a promised modification as basis for enforcing a modifying agreement despite the absence of fresh consideration ▪ Simply performing its duties as promised under the original agreement 3. Mutual release ▪ A rationale is “fictitious” when the “rescission” and new contract are simultaneous. ▪ If both destroys the preexisting duty, and then can be liberated to do contract 2 ▪ If there is duress then not enforceable 28 4. TERM a. EXPRESS 1) Do the parties attach the same meaning to the terms? • Yes - These are the terms governing (Rest. 201(1)) • No - Go to (2) 2) If parties disagreeing on meaning of an express term: 1. No contract when: i. Parallel ignorance (Rest. 201(3)) ➢ Unless Court chooses to fill in the gap. Go to Gap Filler. (Frigaliment v. BNS) (Joyner v. Adams) - finding that both sides did not have the same understanding of the phrase “completed development.” Both sides have equal bargaining power, and both participated in the drafting so the interpretation against the drafter did not apply. Need to know what the parties intended through Gap Filler. The court did not consider parallel ignorance situation and grant no contract option. ii. Parallel awareness 2. Contract operative by one party’s meaning • One party doesn’t know nor has reason to know > one knows or has reason to know (Rest. 201(2)) • Determine who has reason to know: Go to Gap Filler. GAP FILLER (Four-corner < Plain Meaning Rule (patent ambiguity) - only look to evidence when the meaning of the word is ambiguous < Latent Ambiguity - will look at all evidence before deciding whether there is ambiguity). - Should only turn to extrinsic evidence when there is no clear meaning in the text because Courts don’t like and is skeptical of extrinsic evidence (Common Law ≠ Restatement) I. Plain Meaning Rule a. Common Law: Patent (intrinsic) Ambiguity: only look to extrinsic evidence when there is ambiguity on the face of the term i. Is there ambiguous on the face of the contract? (Frigaliment v. BNS) ▪ Yes: Use Gap Filler tools (Interpretation of the Contract) b. Restatement/Corbin (Modern Approach): Latent (extrinsic) Ambiguity → Analyze all evidence admissible unless Parol Evidence prevents (i.e. when contract terms contradict the interpretation) and THEN decide whether the term is ambiguous or not (Rest. 210(3)) o Parol Evidence (Rest. 213) 29 1. What is the level of integration? a. Completed integration: complete and exclusive final version of all the terms (Rest. 209) (Rest. 210) ▪ Indication of completed integration i. Legal obligation, material terms and items ii. Merger Clause iii. Parties expressly deem it is a contract (not memo / letter of intent) b. Partial integration: an integrated agreement other than a completely integrated agreement that includes final statement of some of the terms 2. Use + Permissibility of evidence a. Completed integration ▪ Explain only ▪ Cannot add or contradict terms (Thompson v. Libby) (Rest. 215) b. Partial integration ▪ Add or explain only ▪ Cannot contradict terms 3. Exception (Rest. 214) 1) Explain ambiguity a. Common Law: Plain meaning rule (Gap Filler only when there is ambiguity within the four-corners of the contract) b. Restatement’s view: can admit evidence for interpretation but must stop short of contradiction. Two steps: i. Considers evidence that is alleged to determine the extent of integration ii. “Finalizing” the court’s understanding by using the parol evidence rules to filter out extrinsic evidence that would vary or contradict the meaning of the contract. c. Gap Filler (Taylor v. State Farm Mutual Insurance Co.) 2) Subsequent agreements made AFTER the finalized agreement (modification) 3) Oral conditions (Rest. 217) - The whole agreement’s effectiveness is based on an oral condition 4) Illegality (Rest. 214(d)) - Evidence to show that the agreement is invalid for any reason, such as fraud, duress, undue influence, mistake, illegality 30 ▪ Go to Defense i. Fraud a. Fraud in Execution always accepted b. Fraud in Inducement 1) Majority: parol evidence is excused in cases of fraudulent inducement even when the writing is completely integrated or contains a merger clause 2) Minority: Sherrodd v. Morrison-Knudsen Co. - The allegation of fraud must not directly contradict the express terms of the contract ▪ Ex: Merger Clause, Signed Agreement, when party has taken steps to preclude the fraud claim 5) Equitable remedy / restitution - Court only allow reformation of contract when party can show a “clear and convincing evidence: that the parties really did intend their written agreement to contain the term in Question. 6) Collateral Agreement (Rest. 216) - Do not expect this kind of evidence to be within the integrated contract ▪ Not separate and independent in character ▪ Warranty is not a collateral evidence because it is directly related, and a reasonable person would expect it to be within the agreement (Thompson v. Libby) INTERPRETATION TOOLS (Rest. 202 - 203) A. Text-oriented 1) Use ordinary and technical meanings, as appropriate 2) Words are known by the company they keep 3) Expressing one excludes the others 4) If you use specific terms, then general terms are the type that specific terms indicate B. Intent-oriented 1) Purpose of the parties ▪ Parties have conflicting interests, so it is difficult to determine the common purpose 2) Interpret contract as a whole ▪ Try to make it reconcilable so don’t make things out of context to make it consistent 3) Interpret contract to make it valid ▪ Reasonable, lawful, and effective in nature 4) Specific governs over general 31 ▪ Where there is conflict between two provisions, then you choose the ones that focus on the details in question over the general provision 5) Handwritten trumps the printed ▪ If parties have negotiated, then presentation gives more deliberation C. Extrinsic evidence of intent 1) Course of performance ▪ Interaction between the parties with respect to the same contract at issue ▪ Like Course of dealing, but particular to this contract only ▪ Restatement 202(4), UCC 2-208 2) Course of dealing ▪ Concerns evidence between the particular parties to the transaction (Rest. 223) 3) Trade usage ▪ Regularity within a place, could be regional but conventionally is general for a trade so that you can justify the expectation in every given context (Rest. 222) D. Principles not related to intent 1) Interpret ambiguities against the drafter (Rest. 206) - To repair for the harm that the drafter may have worked to their benefits ▪ Exception: Cases that do not reveal any disparity of bargaining power between the parties (Joyner v. Adams) 2) Interpret contract to favor the public interest ▪ Grants of public franchise ▪ Covenants for property in which there are discriminations ▪ If you encounter this problem, then you may interpret this as a way to avoid the problem b. IMPLIED - Implied Term: a term that court does not find in the parties’ agreement, but that the court holds should be “implied by law” - made a part of that agreement by operation of the rules of law rather than by agreement of the parties. ▪ Supply terms that parties would probably have agreed to ▪ Rely on public policy and fairness Missing terms - Agreement to agree (Common law ≠ Rest/UCC) i. Common law 32 a. Majority approach: If courts can supply reasonable terms (“gap filler”) for those that are missing, these terms will be supplied only where they are consistent with the parties’ intent (Rest. 204) (Rest. 27) • Go to Gap Filler. b. Minority approach: contract not enforceable until ALL essential terms are included ▪ Terms must have future ascertainment (formula, method) ▪ Courts do not decide ambiguity between parties ▪ If an essential term is missing for future agreement, there is no legal obligation until such future agreement. ▪ Walker v. Keith - finding that the renewal lease for a small lot was not enforceable for uncertainty because the rental price was based upon future agreement as the date of the renewal, and they did not agree to a new price) ▪ Renewal options in lease is not an exception ii. Restatement - Letter of intent - Prior negotiations before a formal agreement can be contract through mutual assent (Quake Construction, Inc. v. American Airlines) (Rest. 27) ▪ Unless indicate that it is only preliminary negotiation by parties through a clear intent not to be bound ▪ Go to Parol Evidence to find out parties’ intentions iii. UCC a. 2-204(3). Formation in General: can be a contract even when missing terms as long as: ▪ Parties intend to make contract ▪ Basis for remedy b. UCC 2-305. Open Term Price: The parties can conclude a contract for sale even when the price is not settled yet (“price to be set by seller at time of delivery”) as long as there is good faith in dealing and intention to be bound. Implied covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing a. Covenant of Good Faith and Fair Dealing - Both UCC 1-304 and common law Rest. 205 imposes a duty of good faith and fair dealing on each party to a contract with respect to performance and enforcement ▪ Protect the “reasonable expectations” of the contracting parties considered in light of background contexts ▪ Avoid putting one party at the mercy of the other 33 ▪ Usually no contradiction with Parol Evidence Rule because the implied covenant does not seek to alter or override an express term ▪ Implied good faith seeks to 1) consider parties’ expectation of parties, and 2) purpose for which the contract was made o Bad Faith a. UCC - Two-step analysis and merchants must abide by both of the standard b. Common Law / Restatement - Bad faith: it is an unreasonable behavior if it allows interference in the intent to deprive the other party of the “fruits of the contract” as to violate their expectation o Circumstances that can introduce parol evidence: 1) When a term, not expressly set forth in contract, must be added to reveal parties’ expectation (implied obligation to use reasonable effort) (UCC 2-306(2)) i. Reasonable Effort - A promise to use reasonable effort requires more from context (Wood v. Lucy, Lady Duff) - finding that the contract was NOT illusory and have valid consideration because although P did not bind himself to anything, his action implied that there is consideration by fulfilling his “exclusive” obligation such as 1) account on monthly payments for fees, secure IP protection, split profit 50/50 ▪ Include: good faith, reasonable based on abilities of the party, the means available to it, and the expectation of other party, or diligence ▪ An implied obligation to use reasonable efforts will prevent a somewhat indefinite promise from being illusory. 2) When there is concern that a party may have used a contract term in bad faith that needs compensation ▪ Seidenberg v. Summit Bank - finding that D was acting in bad faith when D frustrated P’s expectation of being allowed to work until retirement age and D used insufficient energy to create leads, and deprived P of expected profits despite the express contractual terms. → Implied good faith requires that parties do not intentionally frustrate the purpose of entering into the agreement. 34 ▪ Bargaining power is an important factor though not determinative (Sons of Thunder - finding that although the contract expressly stated that contract’s term is 1 year and was terminable on 90’s day notice, D was breaching good faith when it prayed on P’s lack of sophistication and desperate financial straits). → Go to Parol Evidence to find the true intentions/expectation of parties when entering the agreement. 3) When there is concern about a party’s discretion expressly granted in a contract’s term i. Satisfaction Clause a. Majority Approach (Objective Approach) (Rest. 228): satisfaction is judged by a reasonable person standard when the contract involves commercial quality, operative fitness, or mechanical utility (Morin Building Products Co. v. Baystone Construction, Inc.) - finding that an aluminum wall for a factor, despite the contract reserve the right to reject the work to D, should be judged using an objective standard of a reasonable person, even when it involves personal aesthetics, especially when the new wall is subject to the same flaw. b. Minority Approach (Subjective Approach): when it comes to “personal aesthetic,” satisfaction depends on the owner’s good faith judgment ▪ The performing party must recognize this is subjective ▪ Hard to show evidence that it is acting in bad faith ▪ Does not need the contract to be MADE in bad faith; only require the subsequent in the execution to be in bad faith ➢ Go to Parol Evidence (Locke v. Warner Bros) finding that even when the contract is based on personal aesthetic, D should not have bad faith in deciding to upset P’s expectation but should be “honest” dissatisfaction. Evidence of explicitly telling Locke that her work would not be made into films is evidence of bad faith allowed by Parol Evidence. 35 5. WAS THERE A BREACH? 1) Is there an express condition to a party’s performance in the contract? (Rest. 224) Is the express condition stated in unambiguous language (such as “if,” “unless,” and “until”)? i) ▪ Yes: requires strict compliance ▪ ▪ If condition fails, the obligor is discharged from further obligations If in doubt, Restatement prefers an interpretation that a term or event is not an express condition in order to reduce the risk of forfeiture (Rest. 227) → only a promise unless its occurrence was a material party of the agreed exchange (Rest. 229). ▪ Look to parties’ intent. ii) Is it a promise/constructive condition? ▪ Yes: require only “substantial performance” ▪ If condition fails, the breach does not necessarily discharge the obligor’s performance and may only give rise to damages. 2) Has the condition been excused by: a. Contract Defense ▪ Go back to Defense ▪ EnXCo Development Corp v. Northern States Power Co. - finding that impracticability is not an excuse to nonperformance of getting an EPCA license before the “Long-Stop Date” because EnXCo had had 29 months and EnXCo was assigned the risk in the contract. b. Disproportionate Forfeiture (Rest. 229) ▪ Severe loss: what is the overall effect on both parties of allowing this condition not to occur? ▪ Was there risk assigned to the injured party? ▪ EnXCo Development Corp v. Northern States Power Co. - finding that there is no disproportionate forfeiture because EnXCo still get to keep all the invested equipment, and the contract is between equal parties, and based on an express termination clause in the contract. Simply Northern States got a windfall because of EnXCo’s failure to act is not enough to justify disproportionate forfeiture. c. Waiver (Rest. 84) ▪ Obligor waives the condition that obligee must do before obligor’s performance ▪ Obligor may be under a duty to perform despite the nonoccurrence of that condition ▪ Material conditions are not waivable, unless other party (obligee) has given consideration for waiver or obligee’s reliance (based on obligor’s expression of intention not to insist on it, followed by the obligee’s reliance on that manifestation of intention) 36 ▪ If both parties’ obligations are conditioned this thing occur, then either one of them can invoke the non-occurrence as a ground to invoke. Both have to waive that in order for them to clear the contract over. If only one side waives, and the other insists, then have to examine who is at issue here d. Prevention (Rest. 245) ▪ The obligor/promisor wrongfully hinders or prevents the condition from occurring ▪ When the condition is somewhat within the obligor’s control, the obligor is likely to have the obligation to attempt to cause the condition to occur (good faith) ▪ Example: inaction or wrongfully preventing the obligee from fulfilling his performance. 3) BREACH i. Is the breach of an express condition or constructive condition implied by rules of contract? a) Express condition: Strict compliance → the other party can stop performing. • Some courts only apply strict compliance for material terms • Some courts hold that under strict compliance, materiality is not a factor b) Constructive condition: Analyze the nature of the breach. Go to ii) ii. Is it a material breach? - Analyze Rest. 241. (a) the extent to which injured party will be deprived of benefit which he reasonably expected; (b) the extent to which the injured party can be adequately compensated for the part of that benefit of which he will be deprived; (c) the extent to which the party failing to perform or to offer to perform will suffer forfeiture; (d) the likelihood that the party failing to perform or to offer to perform will cure his failure, taking account of all the circumstances including any reasonable assurances; (e) the extent to which the behavior of the party failing to perform or to offer to perform comports with standards of good faith and fair dealing. ▪ Yes: Material Breach - Go to iii. ▪ No: Partial Breach (Rest. 235) → Still must perform - but can get damages (Jacobs & Young v. Kent) iii. Is it a total breach? Ask three question: 1) Would the delay prevent the making of substitute arrangements by the non-breaching party? 2) Does the contract emphasize the importance of performing without delay? ▪ If there is a “time is of essence” clause that requires performance before a certain date, then treat as express condition 37 3) Is the breacher's conduct unreasonable? ▪ No: Material Breach (Rest. 241) → Other side may suspend performance (Rest. 237) ▪ Yes: Total Breach (Rest. 242) → Other side may terminate (Rest. 243) ▪ Sackett v. Spindler - finding that even though the buyer never expressly repudiated the purchasing contract and even often expressed willingness to perform, his delay in making payment justified the conclusion that it was unlikely that buyer would commit to the contract. Therefore, the seller could terminate the contract when the seller has committed a total breach. Anticipatory Repudiation (Truman L. Flatt & Sons v. Schupf) - When the time for performance has not yet arrived, but the likelihood of nonperformance appears substantial. a) By notice: Requires a clear manifestation of an intent not to perform the contract on the date of performance - must be a definite and unequivocal. (Rest. 250) b) By conduct: must indicate that performance is a practical impossibility (ex: insolvency/bankruptcy) → Treat as though it is a breach - One may rescind anticipatory if the other party has neither: (Rest. 256) (UCC 2-611) a. Materially relied upon it; nor (changed his position in reliance on the repudiation) b. Provided notice that it considers the contract repudiated as final. 38 6. DAMAGES a. Expectation Damages - A non-breaching party is entitled to damages that put the non-breaching party in the position it would have been had the contract been fully performed. i) Can he prove the loss with certainty? ▪ Yes: Expectation damages ▪ No: Reliance / Restitution Damages General Damage + Special Damages Incidental loss Expense saved from breach 𝐺𝑒𝑛𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑙 𝑚𝑒𝑎𝑠𝑢𝑟𝑒 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑏𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑐ℎ = 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑖𝑛 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 + 𝑜𝑡ℎ𝑒𝑟 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠 − 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑎𝑣𝑜𝑖𝑑𝑒𝑑 − 𝑙𝑜𝑠𝑠 𝑎𝑣𝑜𝑖𝑑𝑒𝑑 (contract price - cost of replacement/completion) + consequential loss OR (value of what party expected - the value she received) + consequential loss Loss saved by mitigation effort Duty to mitigate a. General Damages - Cover contractual loss (difference between market price and contract price) o Loss in value / General Damages calculation - If the loss in value to the injured party is not proved with sufficient certainty, damages may be measured by: (Rest. 348(2)) 1. Cost-to-complete damages - General rule - (contract price - cost of replacement/completion) ▪ Especially for cases of defective or unfinished construction work ▪ If there is any windfall gain by the nonbreaching party made in reasonable effort, the breaching party must also bear this cost. ▪ Handicapped Children’s Education Board v. Lukaszewski - finding that the employee must also bear the windfall gain that the employer had in hiring a more qualified teacher as a replacement to the employee’s termination of the contract) i) Would applying this led to “unreasonable economic waste” or disproportionate gain to the nonbreaching party? o ▪ Yes: use Diminution-in-market value test ▪ No: Analyze Cost-to-complete damages Why Cost-to-complete approach? 39 1) The non-breaching party can expend the damages to receive the bargained-for performance (giving the injured party the benefits of the bargain) 2) Actual injury to P may not be reflected in the market value (personal use), which may ultimately uncompensated the plaintiff. 2. Diminution-in-market value damages - Should only applied where the breacher’s action was unintentional and constituted substantial performance in good faith. i) When there is economic waste or disproportion gain to nonbreaching party ▪ Yes, go to ii) ii) Was the breaching party acting in good faith? ▪ Yes: step ii) (Jacobs & Young v. Kent - finding that the contractor was acting in good faith and only accidentally installed a different pipe instead of the Reading pipe, and the tearing down of the mansion would lead to economic waste, they are allowed to use Diminution-in-market value standard) ▪ No: Use cost-to-complete damages (American Standard v. Schectman finding that since the contractor Schectman breached the contract in bad faith by explicitly not following the contract’s specification by leaving the subsurface foundations undone when the contract wants its removal, they should be liable for the cost of completion instead of the diminution-in-value of the property because of the breach, which is $3,000) o Why Diminution-in-market value damages? - Efficiency ground (Posner): Award of cost-to-restore damages overcompensates the owner ▪ Counter-argument: Even when there is overcompensation or economic waste, if the D acted in bad faith OR if P chose to use the recovery money for other purposes, it is still justified. (American Standard) b. Special Damages (consequential loss) - Example: Loss of profits, loss of product, collateral contracts, business reputation, loss of operating revenue o Limitation on availability of damages 1. Causation 40 - Damages that flow directly from a given type of breach are always recoverable 2. Foreseeability - Hadley Test: D is only liable for foreseeable damages that the breaching party could have contemplated at the time of contract formation (Rest. 351)(UCC 2- 715(2)) ▪ Hadley v. Baxendale (finding that the carrier is not liable for damages that is unforeseeable to him, such as the closure of the mills due to the delay shipment of a broken crank shaft because there may be other possibilities, when the millers did not clearly communicate this consequence at contract formation). ▪ In delivery case: if there is a delay, the damage is the rental cost of replacing the delivering product during the time the goods have not yet arrived (loss of use value of having the goods) ▪ Contract law encourages parties to disclose all possibilities (both parties should take into consideration what possibilities might happen before entering the contract) 3. Certainty (the amount of damages cannot be speculative) (ex: lost profits situation) (Rest. 352) - If not naturally foreseeable, the consequence must be reasonable certainty ▪ Disclosure doctrine: the nonbreaching party must establish their damages with reasonable certainty (ex: using past profits, expert) but don’t need the actual amount ▪ Minority approach: Tactic agreement test - the nonbreaching party must show that not only the special circumstance was brought to the attention of the other party, but also that the other party “assumed consciously” the liability in question ▪ New business rule: courts have become more laxed to allow new business to recover lost profits that they can prove with reasonable certainty, o Collateral contract - An injured party can recover lost profits from a third-party, collateral contract ▪ Floralfax International, Inc. v. GTE Market Resource - finding that loss of profit was foreseeable and although GTE knew about Bellarose’ potential of losing profits, it entered into the contract with Floralfax and assumed the responsibility to pay Floralfax consequential damages and lost profits if Bellarose breached. 4. When justice so requires (Rest. 351(3)) - If there is a big difference between consequential damages and contract price, court will limit the damages to a specific ratio. 5. Contract - Contract itself may establish the limit of damages by providing value or saying that there are no consequential damages recovery 41 Duty to mitigate i) Can the nonbreaching mitigate the loss? ▪ The nonbreaching party has an obligation to take reasonable steps to reasonably minimize their loss arising from the breach ▪ If unclear, the nonbreaching party must ask for reassurance if it suspects that the breaching party lacks authority Once party receives the other party's breach The nonbreaching party must stop immediately to avoid more loss Why should stop performing contract The nonbreaching party can sue for damages incurred up to the time of the breach Why should complete contract - Stopping performance even when the contract is breached might lead to spiral breaching on the nonbreaching party with sub- - Accruing more damages would lead to waste without compensation contracts (employees/sub-contractors) - Earn some profits to make it salable later as mitigation - Even if the remedy is not profitable, if the nonbreaching party makes a reasonable but unsuccessful attempt at mitigation, they can still count this as [Other Loss] (Rest. 350(2)) ▪ Rockingham County v. Luten Bridge Co. (finding that Luten Bridge Co. could not recover for the full amount of the bridge that it has completed AFTER the notice for breach is received) ii) Does the mitigation fall into any of these exceptions? 1) Without undue risk or humiliation (Rest. 350(1)) 2) Same mitigation opportunity available to both breaching and nonbreaching party ▪ Majority: the nonbreaching party still have an obligation to perform the reasonable effort ▪ Minority: If neither party did, the default party cannot assert that the nonbreaching party failed to mitigate loss (Wartzman v. Hightower) - finding that Hightower did not have a duty to mitigate the loss from the failure of their business when Wartzman can also invited the financial expert but did not. ▪ Exception to exception: Even if the remedy is not profitable, if the nonbreaching party makes a reasonable but unsuccessful attempt at mitigation, they can still count into recovery as [Other Loss] (Rest. 350(2)) iii) Example of duty to mitigate 42 a. Construction contract - The injured contractor must stop working once the contract is breached b. Employment contract - In a wrongful firing of an employee, the employee can choose to mitigate by looking for a comparable job. ▪ Majority approach: burden of proof is on the employer (as wrongdoer) to prove that there is a replacement that the employee did not find. ▪ Minority approach: it is the employee’s burden to show that there is no comparable replacement c. Sale of Goods - Buyer is required to attempt to find substitute goods when a breach of contract occurs. b. Reliance Damages (Rest. 349) - Put nonbreaching party in the position he would have been had the contract never been made (make victim whole again) - Apply when the expectation damages cannot be proved with certainty: measure out-of-pocket expenditures that P had to spend, and maybe forgone opportunities/gain P would have made had she not relied on the promise of the Defendant. 𝑅𝑒𝑙𝑖𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒 𝐼𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑡 = 𝐸𝑥𝑝𝑒𝑛𝑑𝑖𝑡𝑢𝑟𝑒𝑠 𝑚𝑎𝑑𝑒 𝑓𝑜𝑟 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑚𝑎𝑛𝑐𝑒 − | 𝒍𝒐𝒔𝒔 ℎ𝑎𝑑 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑛𝑡𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑡 𝑏𝑒𝑒𝑛 𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑓𝑜𝑟𝑚𝑒𝑑 | Breacher has the burden of proof ▪ | Contract price - market price | Wartzman v. Hightower Productions, Ltd. - finding that the law firm was in breach because it failed to sell stocks to fund the promotion where it could foresee that the full performance is required for success of the venture. The damages based on reliance of the law firm’s action to invest, acquire shareholders, employees) ▪ Walser v. Toyota Motor Sales - finding that Court has the discretion to limit the recovery to only out-ofpocket reliance in thinking that the letter of intent was an assurance that they would be granted the Toyota dealership when there are still some finalization and requirements to be done + Toyota promptly revokes the assurance within 2 days. Therefore, the recovery should be limited to the difference between the actual value and the amount paid for the property. Limitations on recovery for reliance damages (Rest. 352(a)) 1. Causation 2. Foreseeability 43 3. Certainty 4. When justice so requires - At Court’s discretion: a. Allow expectation damages, no matter what the promise is (reliance is enough to seal the deal) ▪ General - Subcontractor case: Drennan - usually award expectation because this is on the verge of a contract, but Court stops short at PE instead. ▪ Awarding general contractor injured by the breach of subcontractor’s bid even when there is no formal contract. Calculated: “breacher’s bid - cost of finding a replacement” ▪ Minority: Some courts do not allow a party to recover for reliance costs incurred before the contract was made. b. Limit to reliance damages (to prevent putting the nonbreaching to be in a better position they were in/overcompensate) ▪ The promisee was partially responsible for his failure to bind the promisor to a legally sufficient contract o Reliance evaluation: 1) Uncertainty 2) Disproportionate of expectation damages to amount reliance damages ▪ The contract price should limit the recovery only of essential reliance damages (cost of performance the contract) ▪ Should not limit the amount for collateral transactions (“incidental reliance”) 5. Equal opportunity to mitigate the damages 6. Losing Contract (Rest. 349) - Recovery should be offset by “any loss that the party in breach can prove with reasonable certainty the injured party would have suffered had the contract been performed” - Burden is on the Defendant to show that contract would have been a losing one. 44 c. Restitution Interest (Rest. 371) (based on the gain of the defendant) - Targeting the value that it has conferred to prevent the breaching party from gaining the benefits. - The unjust enrichment by the breaching party must be made with reasonably certainty 𝑅𝑒𝑠𝑡𝑖𝑡𝑢𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 𝐼𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑡 = 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑏𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑐ℎ𝑖𝑛𝑔 𝑝𝑎𝑟𝑡𝑦 𝑟𝑒𝑐𝑒𝑖𝑣𝑒𝑑 𝑶𝑹 𝑖𝑛𝑐𝑟𝑒𝑎𝑠𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑝𝑒𝑟𝑡𝑦 ′ 𝑠 𝑣𝑎𝑙𝑢𝑒 what it would have costed for a replacement / Contract price Why Restitution > Reliance (Market value restitution) - Restitution aware may result in a higher payoff to the plaintiff than would reliance/expectation because the damages does not take in loss from a losing contract - For losing contract, while reliance may be easier to show because of clear expenses, the loss had contract been performed may drive recovery to 0. ▪ US ex rel. Coastal Steel v. Algernon Blair - finding that the subcontractor was justified in terminating the performance when the Defendant - General contractor refused to pay for the crane rental because it was a material/total breach. Even when the contract will turn out to be a losing one, the recovery on restitution ground is to prevent unjust enrichment, so the subcontractor should be able to recover for its labor and use of equipment. o Full performance Exception (Rest. 373(2)): Under market price, when one party has performed 100% and the only thing left for the other party is to pay, the market price is limited to the price of the contract. → The party must recover on Expectation damages rather than restitution ground. Mutual discharge - If the performance obligations imposed by the contract has been “discharged” by Rest 375 (Statute of Frauds), 376 (Restitution when contract is voidable because of lack of capacity, mistake, misrepresentation, duress, undue influence, breach of fiduciary duty), 377 (restitution when contract is discharged due to impracticability, frustration of purpose, or failure of condition) → Either or both of the parties may be entitled to restitutionary relief o Restitution for Breaching Party (Rest. 374) Restitution Interest = value of performance - loss caused by the breach a) Majority: permitting the breacher to recover on restitution ground minus the damages from any loss that the breacher did to the contract. - Example: Breaching party made a deposit and later on decided that they don’t want to perform ▪ They should be able to get back what they invested ▪ Will be whichever is less: 45 i. Value of benefit conferred ii. Defendant’s increase in wealth iii. Cannot recover more than contract portion where it can be determined b) Minority: full rendition of the entire performance contracted for was a condition precedent to the right to recover any of the promised compensation, either “on the contract or on restitution basis” (Stark v. Parker) d. Specific performance - Alternative to expectation damages ▪ Most common with unique goods, difficult-to-replace items, and land ▪ City Stores Co. v. Ammerman - finding that City Stores is entitled to specific performance, i.e. making Ammerman make a space for it at the department store when Ammerman breached the contract with City Stores to rent to Sears on the ground that it would be more profitable. ▪ Sometimes used when expectation damages wouldn’t be fully compensated • Expectation damages fail to account for subjective evaluation of unique goods • Even if rare, if something is traded regularly, objective value can be ascertained • However, market value can only say how much next bidder would pay, which would not fully reflect the value for unique goods - An option contract may be enforced through specific performance if its terms are sufficiently definite 1) Are there definite terms? ▪ Special relief will not be denied merely because the parties have left some matters out of their agreement, particularly when parties have agreed on all material terms. 2) Would the injured party be remediless? 3) Difficult of supervising the performance > importance of the remedy? Land or Goods - Factors for Specific performance: 1) Adequacy of remedy at law 2) Lack suitable substitute (uniqueness) (Rest. 360) ▪ Difficulty of procuring a suitably equivalent substitute performance 3) Collectability ▪ Unlikelihood that a damage award would be collectible 4) Definiteness ▪ Cannot prove the damages with certainty 46 5) Hardship in supervision ▪ Building contracts are unlikely to be specifically enforced, both because of the difficulties of supervision and because construction services can readily be purchased on the market with a money award in damages. Personal Services - Court is very reluctant in giving out specific performance 1) How fungible is the service? ▪ Yes: if can be easily replaced, then can hire a replacement ▪ No: Specific performance resemblances indentured servitude