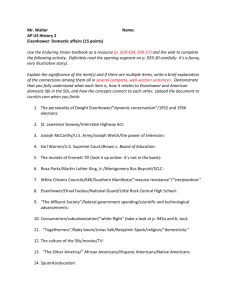

y t i v i t c u d o r P The Manifesto g More in m o c e B o T e id u G y g Your Strate Effective And Efficient made with Introduction “People are frugal in guarding their personal property; but as soon as it comes to squandering time they are most wasteful of the one thing in which it is right to be stingy.” --- Seneca, On The Shortness Of Life Time is our most precious resource. It's something that we can never get back if we were to squander it. It makes sense that we maximise our #1 resource if this is the case. If you are reading this, you probably understand that already. In the next few chapters, I'll be sharing some of my ideas and strategies on how we can best manage our time. These are techniques that have stood the test of time and have been used by the greatest minds in the past century. Some of them you will find useful, others useless. Take what is of benefit to you and leave the rest - that is the best way you can use this resource. The Two Principles Of Productivity Sometime in the late 1800s—nobody is quite sure exactly when—a man named Vilfredo Pareto was fussing about in his garden when he made a small but interesting discovery. He noticed that a tiny number of pea pods in his garden produced the majority of the peas. He was intrigued. As an economist, he was studying wealth in various nations. A thought crossed him: what if this inequality was present in the distribution of wealth as well? To his surprise, Pareto discovered that approximately 80 percent of the land in Italy was owned by just 20 percent of the people. Similar to the pea pods in his garden, most of the resources were controlled by a minority of the players. Pouring through the income records in Britain, he also noticed that approximately 30 percent of the population earned about 70 percent of the total income. As he continued researching, Pareto found that the numbers were never quite the same, but the trend was remarkably consistent. The majority of rewards always seemed to accrue to a small percentage of people. This idea that a small number of things account for the majority of the results became known as the Pareto Principle. It is also more commonly known today as the 80/20 rule. In modern times, it has come to mean that 80% of our results come from 20% of our effort. This is the first principle: that certain actions are more effective than others. In fact, they are disproportionately more effective. Find the few actions that help you accomplish your task quickly. Focus on what gives you 80% and ignore the other 20% - everything else will fall into place once you get the 80 per cent down. Pareto’s principle is the reason why prioritisation is so important. The second principle can be traced to Cyril Parkinson, was a British naval historian who had spent a large amount of his time with the British Civil Service. As a British staff officer in World War II, he observed the numerous inefficiencies caused by a large bureaucracy. Indeed, he noted that the British Colonial Office increased year after year even though the British Empire was in decline. In a satirical article for the Economist in 1955, he discussed how organisations had uncontrolled growth due to their self-serving nature — each department creates work for another. After all, an official wants to multiply subordinates, not rivals. The punchline for his humorous essay was the following: “Work expands to fill the time available for its completion.” In essence, he was saying that we use up the entirety of the allowance we give ourselves. Working without constraints disincentivises you from making optimal decisions. After all, why fret over the small stuff when you don’t have to? Consequently, we spend a good portion of our lives with wasted time. We realise how this adds up only when it’s too late. You may have noticed the following: Doing work at the last minute makes you more productive; you get far more done in that hour than you usually do No matter how much space you have, your belongings will find a way to occupy it — you subconsciously acquire more belongings to fill up that unused space in Satiety comes when you finish whatever that is on your plate; how much there is doesn’t make that much of a difference The solution is to set limits and constraints into your life. The human mind and body adapt quickly. Leave yourself without buffer and you’ll find yourself performing at a higher level. The Psychology Of Productivity There are many strategies out there that help you to work better. In fact, the internet is filled with ideas on you can save more money, lose weight and save time. Most of them are sound and well-intentioned. The question is, why doesn’t it work? The thing is that most strategies and advice centre around you using willpower. If you could just wake up two hours earlier every morning, you would have two more hours of undisturbed time. If you could just save $5 on a cup of latte every day, you’ll have over $1800 at the end of the year. If you could just… Willpower doesn’t work. It’s overrated. Science has shown that our willpower depletes over time, and can be swayed by environmental factors. At its best, it’s a muscle that works at the start of the day when you are fresh and alert. At its worst, it’s something that keeps coming up short, leading you into a downward spiral. What can you do then? The answer is to build systems that work. Have you ever noticed that there are some things you do automatically? You don’t need any prompting or reason to do that something - for instance, you may make your coffee the moment you wake up. The main reason you can do that on autopilot is that it’s easy. B.J. Fogg, head of the Stanford University Persuasive Tech Lab, has an idea he calls “Minimum Viable Effort ”. Here’s what he has to say about building habits: Make it tiny. To create a new habit, you must first simplify the behaviour. Make it tiny, even ridiculous. A good tiny behaviour is easy to do — and fast. Productivity can be a habit. To get there, the only strategies that work are small tweaks that help you work more effectively and efficiently. Working smart is easier to nail down than working hard; once you get to a certain stage you’ll be intrinsically motivated to put in the effort yourself. The other aspect of psychology is understanding what motivates you. For instance, the best productivity systems don’t provide incentives - in fact, they focus on the very opposite. Most strategies involve pain and disincentives, because of this phenomenon known as loss aversion. Pain is a powerful motivator; nothing works better than a perceived threat to get yourself working harder and faster. With this in mind, I’ll share some strategies you can implement easily into your life. The only catch? You need to use them one at a time. Get started on too many of them at once, and you’ll quickly be overwhelmed. r o F s ie g e t a r t S id p a R Productvitity 1. The Eisenhower Matrix 2. Eat That Frog 3. Minimum Effective Dose 4. The Pomodoro Technique 5. Put A Gun To Your Head 6. The Default Answer You Should Have To Invitations The Eisenhower Matrix Dwight Eisenhower has had one of the largest impacts on the world in the past 100 years. His achievements in his lifetime across many fields are nothing but spectacular. In many ways, he lived an extremely productive life. Eisenhower was the 34th President of the United States, serving two terms from 1953 to 1961. Before becoming president, Eisenhower was a five-star general in the United States Army, served as the Supreme Commander of the Allied Forces in Europe during World War II, and was responsible for planning and executing invasions of North Africa, France, and Germany. At other points along the way, he served as President of Columbia University, became the first Supreme Commander of NATO, and somehow found time to pursue hobbies like golfing and oil painting. He accomplished this by understanding the difference between the important and the urgent. In fact, he had a saying he held dear to: What is urgent is seldom important and what is important seldom urgent. Evidence of this can found in the system he used to classify his tasks. We know this today as the Eisenhower Matrix. The beauty of the system is that it can be continually used for making decisions over and over again. And like anything in life, consistency is the hard part. This quadrant forces you to make conscious decisions on how you are going to spend your time. You have to confront the brutal truth on how you waste your time. I now know that mindlessly reading articles and binge watching TV shows are what’s costing me my time. Ownership of my time usage allows me to improve and become more productive. What's worth noting is how we often neglect activities in the top right quadrant - things that are important but not urgent. These are activities that create a great deal of value over time, and hence we must be mindful of them. They will quietly make or break you. When Eisenhower said, “What is important is seldom urgent and what is urgent is seldom important”, he was warning us not to be caught in the thick of thin things. In today’s age where we have so many venues of entertainment and information, it is worth bearing his advice in mind. Eat That Frog “If the first thing you do when you wake up in the morning is to eat a live frog, then nothing worse can happen for the rest of the day.” This is one of the key messages of Brian Tracy’s book, Eat That Frog , which discusses how we can accomplish more things done through prioritisation and behavioural psychology. His question is this: what’s the one thing you can do that will make the rest of the day better? Guiding the ‘Eat That Frog’ strategy is Pareto’s Principle: that there’s one thing that will dramatically affect your results. The beauty of Brian Tracy’s strategy is that it’s surprisingly easy to implement. All it takes is a rearrangement of priorities to ensure that all work done is effective and not just a farce. To paraphrase Jim Rohn’s words, this prevents you from majoring in minor things. You can look at this as a micro-application of the Eisenhower matrix - it teaches you to focus on the big wins. In other words, it tells you to focus on important tasks, whether they are urgent or not. It allows you to be proactive instead of reactive to events and deadlines. The other tenet of this strategy is Tracy’s insistence that the primary task cannot be abandoned until it’s complete. The urgency will generate action and inspire more progress instead of procrastination. Minimum Effective Dose There seems to be a preoccupation with being busy. Somewhere down the line, busy became synonymous for productive work. As a result, we spend most of our time today busy, hoping that we’re doing more. But is that necessarily true? Doing more things does not necessarily mean that you are becoming more effective. Oftentimes it’s a classic case of less being more: the time you invested in a particular task could be better used elsewhere. In his book, The 4 Hour Body , Tim Ferris popularised the concept of the minimum effective dose. Put simply, it means the smallest dose that will produce a specific outcome. To illustrate his example, he writes: “To boil water, the minimum effective dose is 212 degrees Fahrenheit (100 degrees Celsius) at standard air pressure. Boiled is boiled. Higher temperatures will not make it “more boiled.” Higher temperatures just consume more resources that could be used for something else more productive.” It’s a simple idea and one that most of us have definitely encountered in school. How many of us have turned in assignments or work that we know will definitely get us a certain grade? We know that 70% might be an ‘A’ grade, 60% a ‘B’ grade and anything less a ‘C’ grade. Consequently, we do only as much as we need to: one does not need to put in more effort to move from 60% to 69% if the only desire is a ‘B’ grade. This is guided by the law of diminishing returns, where past a certain point additional input is simply not warranted. Ideally, we should be doing work in the green zone. In reality, it is difficult to identify that we’ve passed the point of diminishing returns; much better to put in more effort and be safely in the orange zone. But there should be no reason why we should be working closer to the green than the red zone most of the time. At the heart of the minimum effective dose is the understanding that every action comes with an opportunity cost. One cannot possibly be the best at everything - better to focus immensely on what truly matters to you and give just the necessary amount of effort in other aspects of life. In this regard, the minimum effective dose is a good principle for deciding how much energy you should devote to a task. The Pomodoro Technique In fitness, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) has caught on because of its immense benefits. Because of the intensity of the workout, your body makes tremendous adaptations which does not typically happen in traditional endurance training. The Pomodoro Technique? Think HIIT for time management. The Pomodoro Technique was invented in the early 90s by developer, entrepreneur, and author Francesco Cirillo. Cirillo named the system "Pomodoro" after the tomatoshaped timer he used to track his work as a university student. The methodology is simple: When faced with any large task or series of tasks, break the work down into short, timed intervals (called "Pomodoros") that are spaced out by short breaks. This trains your brain to focus for short periods and helps you stay on top of deadlines or constantly-refilling inboxes. With time it can even help improve your attention span and concentration. These short intervals can be broken down into 25-45 minutes. During this time, you cannot allow any interruptions. If this happens, you have to stop work immediately and take a break. Instead of a 3 hour study period, 4 Pomodoros of 45 minutes each might be more beneficial. The rest periods between each interval also help in the consolidation of information and has been associated with spurts of creativity. No matter what field you work in, this method can be applied in your daily work. How do you prevent yourself from getting distracted? Cirillo suggests postponing the distraction where possible. In fact, he offers a framework for doing so: 1. Inform the other distracting party that you're working on something right now. An autoresponder might be of use here if your job allows for it. 2. Negotiate a time when you can get back to them about the distracting issue in a timely manner. 1. Schedule that follow-up immediately. 2. Call back the other party when your Pomodoro is complete and you're ready to tackle their issue. Of course, not every distraction is that simple, and some things demand immediate attention—but not every distraction does. Recognising this not only allows you to stay in a state of Flow and be more productive, ut also gives you control over your day. Put A Gun To Your Head In the northeast of Kyoto, there lies a mountain known as Mount Hiei. On that mountain resides the Tendai Buddhist monks, more commonly known as the marathon monks. They believe that enlightenment can be achieved during one’s lifetime, but only through extreme self-denial. The most famous of their practices is the kaihōgyō, which translates to ‘circling the mountain’. During this seven year period, there is a 1,000-day challenge where the monk must run a marathon daily. It is from this uncommon practice from which the marathon monks derive their name. The 1,000-day challenge is broken down into ten smaller challenges of 100 days each. On their first 100 days, they must run 30 km daily. This distance goes up incrementally as the monk goes further into this endeavour — up to 84 km daily in the 7th year. The distance they have to cover is astounding. It is rare that a monk embarks on the kaihōgyō, and even rarer that one completes it. And yet, the sheer distance is not the craziest part of the challenge. There’s another component that makes kaihōgyō different from any other ultra-marathon or physical feat. During the first 100 days, the monk attempting the challenge can withdraw at any time. Past that, there is no such opportunity. He must either complete thekaihōgyō or take his own life.There is no alternative. It is literally a do or die situation. This is the story behind every single impossible feat that has been done. It’s a simple philosophy: raise the stakes and increase the pain of failure or inaction. We are hardwired to pursue pleasure and escape pain. This is the reason why we avoid challenges and unpleasant tasks, even though we binge on unproductive and detrimental activities. It’s something everyone can do. For example: Want to get over your fear of public speaking? Sign up for the next speaking competition at your local Toastmasters club. Never have time for exercise? Register for the next half-marathon. Have writer’s block? Announce to the entire world when your next piece of work is coming out before you begin. At its core, this strategy capitalises directly on Parkinson’s law. It recognises that constraints push us to do things we never would. Apply this to small facets of your life, and you just might have extraordinarily big changes that positively impact your entire life. The Default Answer You Should Have To Invitations No. I’m convinced that’s the answer you need to give when asked for your time. Because most of the time, the question results in a large time sink. That is time that you will never get back. ‘No’ is the answer when asked to join weekend dinners, late night parties and water cooler gossip. It’s the answer to creating more time. It’s the only way you can create more time. It's part ironic and part crazy that we are a stage where engagements are killing us. It used to be that people asked for your time only when they either really needed your help or wanted to connect with you. These days, everyone wants a piece of you. If you want to do things that matter to you, you have to say no to things that don’t matter. At first glance, it's a scary thought. But look at it another way: Saying ‘no’ to one thing allows you to say ‘yes’ to another. ‘ 'No’ is the first step to taking back control of your own time. 'No' is the only way to have enough time to work on things that matter to you. 'No' is how you can say 'Yes' to your dreams. What's Next? You've come to the end of the report. So what's next? If this has been of any use to you, please go ahead and share this report with your friends and family. There is no higher compliment you can pay me by spreading the work that I've produced. Here's the link you can use to share this report: subscribe.constantrenewal.com/connect If it's been lousy? Drop me a line. Simply write to 'louis@constantrenewal.com'. I read every response I get and will be happy to talk about how I can improve The Productivity Manifesto. Either way, you can head down to my blog, Constant Renewal , where I share ideas on how we can live more purposefully and productively. I promise you'll learn something new and useful. made with