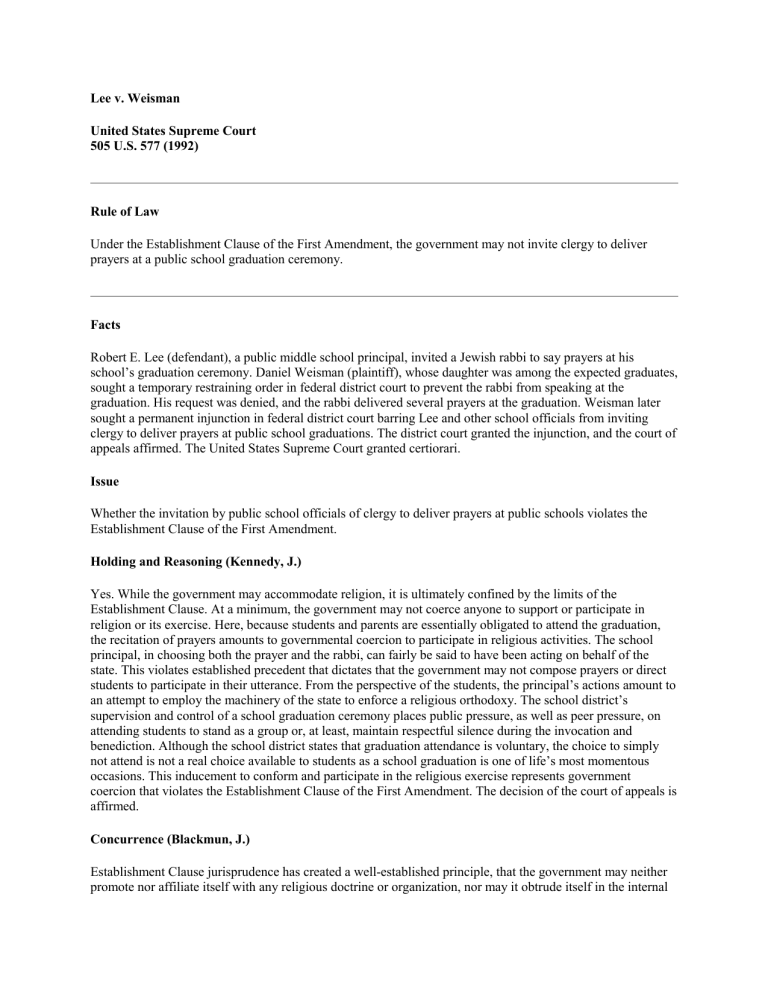

Lee v. Weisman United States Supreme Court 505 U.S. 577 (1992) Rule of Law Under the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment, the government may not invite clergy to deliver prayers at a public school graduation ceremony. Facts Robert E. Lee (defendant), a public middle school principal, invited a Jewish rabbi to say prayers at his school’s graduation ceremony. Daniel Weisman (plaintiff), whose daughter was among the expected graduates, sought a temporary restraining order in federal district court to prevent the rabbi from speaking at the graduation. His request was denied, and the rabbi delivered several prayers at the graduation. Weisman later sought a permanent injunction in federal district court barring Lee and other school officials from inviting clergy to deliver prayers at public school graduations. The district court granted the injunction, and the court of appeals affirmed. The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari. Issue Whether the invitation by public school officials of clergy to deliver prayers at public schools violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. Holding and Reasoning (Kennedy, J.) Yes. While the government may accommodate religion, it is ultimately confined by the limits of the Establishment Clause. At a minimum, the government may not coerce anyone to support or participate in religion or its exercise. Here, because students and parents are essentially obligated to attend the graduation, the recitation of prayers amounts to governmental coercion to participate in religious activities. The school principal, in choosing both the prayer and the rabbi, can fairly be said to have been acting on behalf of the state. This violates established precedent that dictates that the government may not compose prayers or direct students to participate in their utterance. From the perspective of the students, the principal’s actions amount to an attempt to employ the machinery of the state to enforce a religious orthodoxy. The school district’s supervision and control of a school graduation ceremony places public pressure, as well as peer pressure, on attending students to stand as a group or, at least, maintain respectful silence during the invocation and benediction. Although the school district states that graduation attendance is voluntary, the choice to simply not attend is not a real choice available to students as a school graduation is one of life’s most momentous occasions. This inducement to conform and participate in the religious exercise represents government coercion that violates the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The decision of the court of appeals is affirmed. Concurrence (Blackmun, J.) Establishment Clause jurisprudence has created a well-established principle, that the government may neither promote nor affiliate itself with any religious doctrine or organization, nor may it obtrude itself in the internal affairs of any religious institution. Here, the school district’s action is exactly the type of activity this principle condemns. The government must not only refrain from compelling religious practices, but must also refrain from endorsement, sponsorship, or active involvement in religion. The principal’s action in inviting a rabbi to pray at his school’s graduation is a religious practice prohibited by the Establishment Clause. Dissent (Scalia, J.) The Establishment Clause must always be construed in light of the government policies of accommodation, acknowledgement, and support for religion accepted as part of the United States’ political and cultural heritage. Throughout America’s history, many public ceremonies featuring prayers of thanksgiving and petition have occurred. Prayer has always been a part of governmental ceremonies and proclamations. There is no reason to hold public school graduation invocations and benedictions unconstitutional while recognizing that prayer in other governmental ceremonies is a vibrant, permissible aspect of American society. The majority is wrong to hold that students are obligated through “psychological coercion” to participate in the graduation prayers. Students are free to remain seated while others stand as a passive show of their lack of assent to the prayer. The majority’s opinion is unsupported by evidence of any actual psychological coercion. Additionally, it does not give equal deference to the population of students who favor a prayer at graduation. Nothing in the First Amendment prevents prayer in this solemn occasion. Lynch v. Donnelly United States Supreme Court 465 U.S. 668 (1984) Rule of Law A public display erected in conjunction with a religious holiday does not violate the First Amendment Establishment Clause if it only indirectly or incidentally advances religion. Facts Every year during the Christmas holiday season, the City of Pawtucket, Rhode Island (City) builds a large, public Christmas display. The display includes traditional “secular” Christmas images such as Santa Claus and reindeer figures, as well as a religious crèche. The City originally spent public funds to acquire the display, but currently spends nominal costs erecting and maintaining it each year. Donnelly (plaintiff) brought suit against Lynch (defendant), the mayor and the City in federal district court on the ground that the display violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment. The district court agreed and held the display unconstitutional, and the court of appeals affirmed. The United States Supreme Court granted certiorari. Issue Whether a public display erected in conjunction with a religious holiday violates the First Amendment Establishment Clause. Holding and Reasoning (Burger, C.J.) No. The City’s Christmas display does not violate the First Amendment Establishment Clause simply because it is erected in conjunction with a religious holiday. A public display erected in conjunction with a religious holiday does not violate the First Amendment Establishment Clause if it only indirectly or incidentally advances religion. Whether a public display impermissibly advances religion depends on a case-by-case analysis of the government action involved, rather that application of a strict test or criterion by the courts. The United States has a long and unbroken history of official acknowledgement by all three branches of government of the role of religion in American life. Additionally, the Supreme Court has not rigidly interpreted the First Amendment Establishment Clause as a prohibition on all government advancement of religion or religious holidays. The Court has always analyzed each instance of government action associated with religion on a case-by-case basis. Although it is helpful to consider factors such as whether the government action is motivated by a secular purpose, whether its principal or primary effect is to advance or inhibit religion, and whether it creates an excessive entanglement of government with religion, there is no firm criteria used by the Court to evaluate the constitutionality of government action when connected to religious holidays. The City’s religious display both celebrates Christmas and acknowledges the origins of the holiday. Both of these are valid secular purposes for the display. To completely forbid the display because it is associated with a religious holiday would be an overreaction, as government action that either indirectly or incidentally advances religion has historically been permitted. The advancement of religion by the City is indirect and incidental and best, and thus the display does not violate the Establishment Clause. The decision of the lower courts is reversed. Concurrence (O’Connor, J.) Establishment Clause jurisprudence should be clarified. The current treatment of the Establishment Clause completely ignores the fact that political parties and factions are often defined along religious lines. Additionally, difficulties arise when the government both endorses and disapproves of a particular religion. To examine whether the City of Pawtucket impermissibly endorsed religion by its display of the crèche, it is most useful to determine the message the City hoped to communicate, and the actual message that was communicated. It is unlikely that the City intended to communicate a message of endorsing Christianity by placing a crèche in a display with other Christmas imagery. Additionally, it is unlikely that the endorsement of Christianity was actually conveyed because the crèche was placed near other secular images associated with Christmas. Thus, the “purpose” and “effect” of the display do not constitute an endorsement of religion by the City. Future Establishment Clause cases should be analyzed with this same “purpose” and “effect” inquiry. Dissent (Brennan, J.) The City’s use of public money to maintain and display the religious crèche cannot be interpreted as based on a “clearly secular purpose.” The primary effect of the crèche is to endorse one particular religion, Christianity. It does not matter that the crèche was displayed in the overall “context” of the Christmas holiday, as there is no secular way to view a crèche. It does not matter that the government has previously recognized Christmas as a public holiday containing secular elements. The recognition of Christmas as a “public holiday” does give the City a free pass to include religious imagery in its holiday celebration. Based on Establishment Clause jurisprudence, the government may take reasonable steps to accommodate the ability of individuals to practice religion. It has already done this by designating Christmas as a public holiday. The government may continue celebrating the religious holiday, but must focus on the sectarian basis for the holiday. The government successfully accomplishes this in its recognition and celebration of Thanksgiving; a holiday that began as a religious celebration but is now celebrated for purely secular reasons. In the same way, if the government is to successfully continue the public recognition of Christmas, it must remove the religious element from public celebrations of the holiday or risk violating the Establishment Clause. The crèche is a purely religious symbol, and cannot constitutionally be included in any public celebration of Christmas. Dissent (Blackmun, J.) The majority’s opinion that the crèche is not “religious” enough to preclude its use in secular Christmas displays reduces the Christian significance of the symbol. This is offensive to non-Christians because it permits the continued use of a religious symbol in public displays. However, it also offends Christians by devaluing one of their most sacred religious symbols.