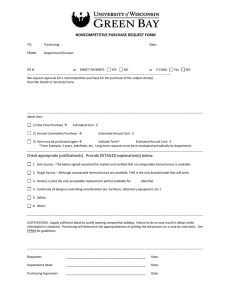

Mohamad G. Alkadry Leslie E. Tower West Virginia University Essays on Equity, Gender, and Diversity Unequal Pay: The Role of Gender Mohamad G. Alkadry is an associate professor and director of the master of public administration program at West Virginia University. His teaching and research interests include organization theory and behavior, social justice issues, and citizen participation. E-mail: malkadry@mail.wvu.edu. Pay disparities between men and women persist in the U.S. workforce despite comparable pay legislation, advocacy, and social change. This article discusses theories of gender pay disparities, such as the glass ceiling, position segregation, agency segregation, and human capital. Using an online national survey, 1,600 responses were collected for four groups of public procurement professionals. The gender wage gap ranged from $5,035 to $9,577. Multiple regression of the data show that gender continues to play a major role in predicting the salaries of public officials in similar positions. Gender and human capital variables predicted between 36.5 percent and 53.9 percent of the variance in pay. Leslie E. Tower is an assistant professor in the Division of Social Work and Division of Public Administration at West Virginia University. Her research interests include domestic violence, health care administration, and women’s issues. E-mail: LETower@mail.wvu.edu M ore than 40 years after the passage of the Equal Pay Act of 1963, pay disparities between men and women persist in the U.S. workforce (Gibelman 2003). A 2003 study by the General Accounting Office (now the Government Accountability Office) found that women earned 79.7 percent of what men earned, even after controlling for occupation, industry, years of work experience, job tenure, number of work hours, time off for childbearing, race, marital status, and education. By comparison, women’s earnings in 1983 equaled 80.3 percent of men’s earnings, an indication that the wage gap is not shrinking (GAO 2003b; see also Schiller 1989). Pay disparities are often attributed to an upward mobility glass ceiling or to the segregation of women in certain “female-dominated” occupations, positions, or agencies. Pay disparities may also be driven by disparities in such human capital variables as professional skills, education, and experience. Attempts to rectify gender pay disparities have been fought largely through legislation, regulation, and litigation. Federal laws include the Equal Pay Act of 1963, which guarantees equal work for equal pay, and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which prohibits sex-based employment discrimination (e.g., hiring, firing, training, promotion, and wages). The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission 888 Public Administration Review • November | December 2006 (EEOC) enforces these two laws. Lawsuits filed by the EEOC may have a greater impact on employment practices than the law itself or lawsuits filed by private law firms. However, the number of EEOC lawsuits is declining, while the number of private lawsuits is rising (Blau, Ferber, and Winkler 2002). This article reviews the existing literature on the major drivers of pay disparities among men and women. This literature includes studies of the glass ceiling and position segregation, agency segregation, and human capital as drivers of pay disparities between men and women, as well as policy options to decrease these barriers to pay equity. The current study analyzes data from a survey of 1,600 public employees to test the effect of gender (among a number of other variables) on the pay of individuals who hold comparable positions in comparable agencies. This article examines the persistence of pay inequity even when men and women have comparable human capital characteristics and have attained similar positions in similar fields. The Glass Ceiling and Position Segregation Pay differences between women and men have traditionally been attributed to the limited number of women in the higher-paying upper levels of organizations. Women are concentrated in lower-echelon positions because of initial hiring at the entry level and a lack of upward mobility within organizations (Guy 1993; Naff 1994; Newman 1994). This traditional conception of pay inequity begs three questions: Are women truly concentrated in the lower levels or positions of organizations? Why are they entering into these lower levels or positions and not elsewhere? And, why do women who enter lower-level positions not advance to higher positions within their organizations? Despite years of equal opportunity and affirmative action efforts, women remain concentrated in certain lower-level positions. In a study of the federal senior service, Mani (1997) noted that women occupied 85 percent of all clerical positions but only 13 percent of the Senior Executive Service positions in the federal public service. Groshen (1991) argued that position or occupational status could account for one-half to two-thirds of the pay gap between men and women. Orazem and Mattila studied occupational segregation within state governments and found that “much of the wage differential between men and women is tied to the different employers and occupational labor markets that men and women inhabit and not to disparate treatment within given employers” (1998, 96). In their study of data from all 18,365 employees in the West Virginia state government, Alkadry, Nolf, and Condo (2002) reported that women accounted for 85.7 percent of “administrative support” jobs and 30 percent of “officials and administrators.” This corroborates the findings of previous studies on the segregation of women in lower-level positions. And, concentration in lower-level positions often means segregation in lower-paying positions. For instance, Alkadry, Nolf, and Condo (2002) reported that only 6 percent of all West Virginia state government employees earning more than $50,000 were women. Historically, women’s have gained access to the public sector through the lower ranks (Guy 1993; Naff 1994; Newman 1994). Guy has noted that “social pushes and pulls result in women gaining entrance to administrative positions while [the] wage gap continues to reveal the relationship between gender and salary” (1993, 285). Most of the sociocultural barriers faced by women entering the public service are centered on the gender typing of employees. Heilman et al. (2004), for example, found that women who broke from traditionally female jobs and succeeded in traditionally male jobs were liked less and personally derogated more often than their male counterparts. Furthermore, they reported, these negative feelings often affected the women’s salaries. Stivers (1993) has argued that women are viewed in society as caring and sensible individuals, whereas images of leaders in the public sector are associated with characteristics that are mostly masculine. Therefore, gender typing and socialization tend to result in the segregation of women in certain agencies, occupations, and positions. Upward mobility within organizations may combat gender segregation, resulting in the progress of women into upper-level and better-paying positions. However, many organizational and sociocultural factors deny women the benefits of upward mobility. Newman (1993) found that a greater proportion of women than men were handicapped in their career advancement by domestic constraints and received lower wages than their male counterparts. Lennon and Rosenfield (1994) studied 13,017 households and found that although married women performed twice the housework as their husbands, both men and women viewed their workloads as fair. In another study, Noonan (2001) found that women performed one and a half times more housework than men and spent more time on female tasks than men spent on male tasks. Noonan also found that the women she studied had less full-time experience, more part-time experience, took more employment breaks, and were less likely to travel extensively for work. In her sample of 10,008 households, women earned an average of $11.55 per hour and men earned an average of $17.56 per hour. For every one-hour increase in the amount of housework performed by women, their hourly wage decreased by 0.3 percent. On the other hand, housework did not have a significant effect on men’s salaries (Noonan 2001). Organizational barriers such as career-development patterns, workplace policies, and mentoring directly affect women’s ability to progress in organizations (Guy 1993). Stroh, Brett, and Reilly (1992) examined the career progression of 1,029 male and female managers employed by 20 Fortune 500 companies. They found that despite similar education and work background, there was a disparity in men and women’s salary increases. Kelly et al. (1991) found that mobility into elite positions occurs at a higher rate for men than women. Guy (1993) also suggested that men seem better able to climb the ladder, whereas women seem less adept. Men are advantaged, after controlling for other variables, in both pay levels and wage growth in all jobs, regardless of gender composition (Kelly et al. 1991). Newman (1993) studied career advancement in the Florida Civil Service and found differences between men’s and women’s barriers to career advancement. Budig (2002) studied female-dominated, genderbalanced, and male-dominated positions and found that men are more likely than women “to be promoted into rewarding male and female jobs, regardless of the gender composition of the job held prior to promotion” (Budig 2002, 274). Stroh, Brett, and Reilly (1992) have suggested that women may have done all they can to break barriers to pay equity and that corporations may need to break some of the barriers to the promotion of women. Not all studies concur that women in organizations are not advancing into higher positions because of organizational barriers. Lewis and Park (1989) examined the effects of age, length of service, education, salary, and gender on differences in turnover rates for men and women. Studying a sample of 1 percent of the entire federal civil service, they concluded that gender is a minor factor in explaining turnover, whereas age, experience, and salary are all more likely to affect turnover. These variables are mostly human capital barriers that some have used to explain the gender pay disparity. Unequal Pay 889 It is obvious from previous studies that women remain concentrated in lower-echelon positions for cultural, organizational, and human capital reasons. They face barriers to advancement, and when they do advance, they generally proceed at a slower pace than men. These barriers form what is labeled the “glass ceiling,” a metaphoric barrier that keeps women in lower-level positions. The segregation of women in lower-level positions causes the pay gap between men and women to widen. This gap may be corrected by strengthening the enforcement of existing equal opportunity laws (Rose and Hartmann 2003). Affirmative action strategies that encourage the placement of women in upperlevel and better-paying positions may help shatter the glass ceiling and reduce position segregation. Organizations can also encourage the hiring, retention, and advancement of women by adopting policies that are friendly to women in the workplace. Such policies may include “making work places more ‘family friendly’ through more flexible hours, providing more job-guaranteed and paid leaves of absence for sickness and family care, encouraging men to use family leave more, increasing subsidies for childcare and early education, encouraging the development of more part-time jobs that pay well and also have good benefits, and improving outcomes for mothers and children after divorce” (Rose and Hartmann 2003, v). Nonstandard work schedules, job sharing, and homebased employment may offer additional flexibility to workers with family responsibilities (Blau, Ferber, and Winkler 2002). Agency Segregation The gender typing of women not only affects the types of occupations they pursue but also the types of agencies they work for. The image of “caring” women results in women working in agencies that provide services such as education and social services (Newman 1994; see also Stivers 1993). “Agency segregation” is the term used to refer to the segregation of women in traditionally female agencies. Newman (1994) has argued that women are more likely to be employed in redistributive agencies than in regulatory or distributive agencies. Newman’s taxonomy of agencies is based on Lowi’s (1985) framework of administrative structures. According to Lowi, redistributive agencies are those concerned with health, welfare, or education and primarily concern themselves with the reallocation of money and provision of services to certain segments of society. Regulatory agencies include environmental agencies, law enforcement agencies, or taxing authorities, which primarily focus on implementing control and regulatory policies. Distributive agencies, such as transportation and parks and recreation agencies, focus on service to the general population. In their study of West Virginia state agencies, Alkadry, Nolf, and 890 Public Administration Review • November | December 2006 Condo (2002) found that 65.7 percent of employees in West Virginia redistributive agencies were women, compared to 23.2 percent of employees in distributive agencies and 33 percent in regulatory agencies. Cornwell and Kellough (1994) looked at clerical, blue-collar, technical, administrative, and professional jobs but found that the nature and number of clerical and technical jobs had a positive effect on the percentage of women in these agencies. They concluded in their study of women and minorities in federal agencies that the female employment share was higher in agencies with a larger proportion of clerical jobs. Agency size, the number of new hires, and union strength did not significantly affect the percentage of women employed in a federal agency. Departments with primarily female-dominated occupations are likely to pay lower wages than agencies with primarily male-dominated positions (Orazem and Mattila 1998). Kelly et al. (1991) examined six states (California, Alabama, Arizona, Texas, Wisconsin, and Utah) and found that female-dominated jobs had lower average wages than male-dominated jobs. Budig’s (2002) findings reaffirm position segregation arguments but also introduce the idea that the integration of women into male-dominated fields and men into female-dominated fields would not close the gap in pay. Men’s economic advantage may persist even after position integration. Research has also shown a considerable gap in pay between men and women even in female-dominated fields such as social work (Becker 1961; Gibelman 2003; Koeske and Krowinski 2004; Gibelman and Whiting 1997). Becker interviewed members of the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) in 1960 and found that women earned 86 percent of the salaries of men. Almost 20 years later, the NASW found that men earned 30.5 percent more than women. More recently, Koeske and Krowinski reported an average pay gap of $3,665 between male and female social workers, even when controlling for years of experience, job role (i.e., administrative or direct practice), age, and years with a master’s degree. Miller, Kerr, and Reid (1999) used the metaphor of a “glass wall” to describe the segregation of women in certain agencies. Based on data from the EEOC, they studied administrative and professional positions in U.S. cities between 1985 and 1993. The authors found that women were severely underrepresented in distributive and regulatory agencies. This finding is consistent with the findings of Newman (1994) and Orazem and Mattila (1998). These researchers also found that salaries in redistributive agencies were lower, on average, than those in distributive and regulatory agencies. Policies to rectify agency segregacomparable worth policies have Policies to rectify agency segre- the potential of reducing gender– tion aim to increase access to education or training in highpay disparities even with the gation aim to increase access paying fields in which women persistence of agency and occupato education or training in are underrepresented and to tional segregation. Women in high-paying fields in which develop new legal remedies to female-dominated agencies or women are underrepresented establish comparable worth occupations will have the potenand to develop new legal remedies tial to earn comparable salaries to (Rose and Hartmann 2003). to establish comparable worth. men or women in comparable Comparable worth extends the concept of equal pay for equal male-dominated agencies or work, codified in the Equal Pay occupations. Act, to include equal pay for comparable work. Comparable worth is determined by conducting detailed Human Capital evaluations of job descriptions and calculating the The barriers to pay equity and equal employment composite effort, skill, responsibility, and work enviopportunity for women and men are far too complironment and then adjusting the pay for different but cated and interconnected to permit the construction comparable jobs (Blau, Ferber, and Winkler 2002; of a useful typology. Organizational barriers are interKillingsworth 2002). Achieving comparable worth at connected with sociocultural and human capital barrithe federal level is unlikely, as federal courts have ruled ers. A discussion of pay equity may attribute the pay that existing antidiscrimination laws do not require gap to women’s tenure in the workforce compared to comparable worth. In addition, federal comparable men’s. Other explanations might attribute it to educaworth bills, such as the Fair Pay Act and the Paycheck tional differences or differences in work experience. Fairness Act, which contain provisions for the develHuman capital theories suggest that investments in opment of guidelines to help employers who volunone’s human capital, such as education, responsibility, tarily engage in comparable worth practices, continue experience, age, and leadership abilities, explain differto receive little attention. ences in success (Kelly 1991). Therefore, it is important to review the literature on human capital drivers Comparable worth at the state level, however, may and their effect on salaries. have more promise. The National Committee on Pay Equity has identified more than 20 states that have The type and quality of education seem to play a implemented some comparable worth pay adjustrole in salary gaps (Rumberger and Thomas 1993; ments. However, Killingsworth (2002) has argued Solomon and Wachtel 1975). Amirault (1994) and that many programs have had a limited and unclear Nieva and Gutek (1981) linked pay inequity to educaimpact, even among the six states with the most ambi- tional disparities. Although education may influence tious initiatives. State comparable worth efforts are pay (Morgan 1997), there is no foundation for arguing likely to continue to encounter cost barriers of implethat women are less educated than their male colmentation, exacerbated by state deficits, as well as leagues. Education is a very important variable that opposition from labor unions and others. Comparable needs to be controlled for whenever studying pay worth, however, would have no impact on workers disparities between men and women. However, educawho attain the same positions across different organition is relevant to pay disparities only if men and zations. Examining such a scenario is what makes our women can be shown to have different levels of current study distinct. education. On a related front, the Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP 2004), which enforces Executive Order 11246, related federal affirmative action, has proposed standards for interpreting systemic compensation discrimination. The OFCCP defines compensation discrimination as “dissimilar treatment of individuals who are similarly situated, based on similarity in work performed, skills, and qualification involved in the job and responsibility level” (OFCCP 2004, 67249; emphasis added). Although comparable worth has clearly been rejected by federal courts and law makers, compensation analysis of similar jobs may become more rigorous, relying on multiple pooled regression analysis. If adopted, these regulations may build capacity for future administrations that are interested in pay equity. In general, Company size has an effect not only on pay disparities but also on pay itself (Langer 2000). Bertrand and Hallock (2001) found that 75 percent of the wage gap in pay between male and female executives of larger companies was explained by company size and by the fact that women were less likely to be chief executive officer, chair, vice chair, or president of these companies. They found no evidence that industry segregation had any effect on the wage gap. Once women executives’ age and seniority were controlled for, the gap in pay fell to less than 5 percent. The level of responsibility an individual bears is likely to affect compensation. Sales volume and organizational size influence an employee’s workload and, consequently, the compensation of that employee Unequal Pay 891 (Langer 2000; Ogden, Zsidisin, and Hendrick 2002). Supervisory responsibilities also influence the compensation of employees (Langer 2000; Ogden, Zsidisin, and Hendrick 2002). People with more responsibility, be it supervisory or financial, would reasonably be compensated at higher levels than those with fewer responsibilities. Years of experience in one’s field and current job tenure also play a role in determining the salaries of individuals (Holzer 1990). Studying purchasing professionals primarily in the private sector, Fitzgerald (1998) found that the gap between the average salary paid to women and men was $17,600. He found that the women in purchasing occupations whom he studied were younger and less experienced than men, had fewer supervisory responsibilities, were in charge of lower purchasing volumes, were less educated, and did not hold as many senior positions as men. However, even when these factors were taken into account, the average compensation of women remained lower than that of men in the purchasing field. Other human capital barriers include leadership abilities (Powell 1988; Rosener 1990) and managerial aptitude (Kelly et al. 1991). Groshen has even argued that “in the human capital model, the wage gap is associated with occupation and with the individual, unless establishments or job cells are sorted by quality” (2001, 468). Conceptual Model The foregoing literature review suggests several directions. First, position segregation is responsible for part of the disparities in pay between men and women. However, this form of segregation plays only a minor role when comparing pay within specified positions or levels. Second, agency segregation plays an important role in widening the gap between male pay and female pay. This role is also more relevant when comparing people in different agency types. Finally, the human capital characteristics of employees, their skills, and their experiences play a major role in establishing the pay of most employees. The literature on human capital drivers of pay and pay disparities does not rule out the potential for these drivers to influence the salaries of men and women. However, it is important to isolate the effect of these drivers from the effect of gender on salaries. This article focuses on human capital and its effect on wage disparities between men and women. The human capital variables include experience, supervisory responsibilities, financial responsibilities, education, organization size, age, and certification. Because respondents were drawn from different labor markets, the labor market competitiveness of respondents and the cost of living in the respondents’ counties must be controlled for (Agron 1996). 892 Public Administration Review • November | December 2006 However, any study of human capital drivers of pay inequity needs to control for position and agency segregation. Controlling for both position and agency segregation may be accomplished by studying pay disparities within the same position levels and the same agency types. Therefore, this study focuses on public procurement officials in different positions. Although the sample used in this study includes procurement officials at all levels of the procurement organization, the results are analyzed separately for each position level. Because the study sample consists of public employees in the purchasing field, three major issues that are unique to public sector wage determination and wage disparities must be noted. First, employees in the public sector are likely to earn less money than those in the private sector (Leenders and Fearon 1997; Muller 1991; Ogden, Zsidisin, and Hendrick 2002). Because the sample used in the present study was drawn exclusively from the public sector, this difference is not likely to have an impact on the internal validity of the findings. Second, there is an expectation that public sector practices will be more sensitive to issues of representation and fairness than those of the private sector (Frederickson 1997; Riggs 1970; Wise 1990). Third, the federal government and several states have historically taken more steps to reduce pay gaps than private sector companies (Killingsworth 2002). The latter two issues mean, if anything, that the pay disparities reflected in public sector samples may be more severe in the private sector. Population and Methodology To gather the data, an online survey instrument consisting of 36 questions was used. The National Institute for Government Procurement (NIGP) is the major professional association for public procurement officials. It was established in 1944 to provide education, professional certification, and technical assistance for public organizations (Thai 2001). An e-mail message with a hyperlink to the online survey was sent to all individuals who work in NIGP member organizations and whose e-mail addresses were available to the NIGP. The e-mail message was sent to 6,747 members; a total of 1,673 individuals responded to the survey, resulting in a response rate of 25 percent. After adjusting for invalid addresses, this response rate increased to 28 percent. As recommended by Lindner, Murphy, and Briers (2001), steps were taken to account for possible nonresponse bias, given the low response rate. The gender, geographic, and agency distributions of respondents were compared to the distribution of the original sample, and there were no apparent signs of nonresponse bias. Furthermore, the average salary of respondents within each of the job classifications was compared to the average salary of the original sample, and again the lack of substantial discrepancies revealed no nonresponse bias (Alkadry and Beach 2003). The total number of respondents represents 28 percent of the entire population, not 28% of a sample drawn from that population. This percentage is considered very reasonable given historical response rates for online surveys (Andrews, Nonnecke, and Preece 2003). The data analyzed included 374 responses from heads of procurement offices, 333 responses from purchasing supervisors and materials managers, 462 responses from buyers, and 160 responses from specialists, technicians, and assistant buyers. To control for the effect of position segregation, the data were analyzed for each of these position classifications and not across positions. Among the respondents, 25 percent worked in state procurement agencies, 22 percent worked in county and regional agencies, and 29 percent worked in municipal agencies. Forty-nine percent of all respondents were female and 51 percent were male. The mean age of respondents was 47 years, and the median was 48 years. The average salary for all respondents was $42,896. On average, respondents had 15.19 years of education and 15 years of purchasing experience. The average tenure with the current employer was 10.77 years. Results As a prelude to the study, it is important to highlight any pay differentials among the different positions in the sample. Analysis of variance was used to analyze the variance of mean salaries among men and women in different positions. As table 1 reports, the pay gap, which consistently favored male employees, was statistically significant for all positions except senior buyers. Depending on the position, this gap ranged from $5,788 to $9,577. Female executives earned 86.5 percent of their male counterparts, female managers earned 87.3 percent of their male counterparts, female buyers earned 87.2 percent of their male counterparts, and female technicians earned 86.6 percent of their male counterparts. Such results are extremely useful in establishing the prevalence of pay inequity in this population. Differences in human capital are the cornerstone of arguments that pay disparities between men and women are driven by factors other than gender. Therefore, this study analyzed mean variances of the key human capital variables. In table 2, the difference for many of these variables is not reported because of its lack of statistical significance. For the variables that were significant, the difference was not always in favor of men. For the heads of purchasing units, the only difference that was significant was years of experience and years of education. Men in this position had more experience and slightly more years of education. For managers and supervisors, men had less experience with current employer, more experience in purchasing, more subordinates, more education, and were older on average. Male senior buyers and associate buyers had more purchasing experience, more education, and were older. Male technicians had slightly higher levels of education than their female counterparts. Like the disparities in pay, human capital disparities also corroborate some previous findings. However, how much of the pay disparities are driven by disparities in human capital characteristics remains unclear. To study this effect, multiple regression analysis was used to predict salary using several human capital variables but also using gender and controlling for labor market competitiveness and cost of living. The regression model was built using 2002 salary (including bonuses) as the dependent variable. Gender and certification were entered as dummy independent variables. Certification captured whether employees held any special purchasing-related expertise. Total years with current employer and total years of experience in purchasing were entered to capture the effect of experience in predicting salaries. To capture the effect of the amount of responsibility attached to respondents, this study used the number of subordinates, annual procurement volume, and number of levels between the respondent and the chief executive officer of the agency. The size of the organization was captured through the number of staff in purchasing units. Age and the number of years of education were also entered. Because the respondents came from different parts of the country, there was a need to Table 1 Pay Disparities in Procurement Positions Heads of purchasing units Managers and supervisors Senior buyers Buyers Technicians, specialists, and assistant buyers All classifications Average Male Salary (including bonuses) Average Female Salary (including bonuses) Female Salary as a Percentage of Male Salary Pay Gap (Sig.) $70,741 $58,809 $48,030 $45,262 $49,318 $61,164 $51,323 $45,812 $39,474 $42,689 86.5 87.3 95.4 87.2 86.6 $9,577 (< 0.0005) $7,486 (< 0.0005) $2,218 (not sig.) $5,788 (< 0.0005) $6,629 (< 0.011) $58,106 $47,712 82.1 $10,394 (< 0.0005) Unequal Pay 893 Table 2 Human Capital Disparities Gender Years with current employer Years of purchasing experience Number of subordinates Years of education Hierarchy Annual procurement volume Number of staff in purchasing unit Number of staff in jurisdiction Age Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Male Female Heads of Purchasing Units Managers and Supervisors 18.93 12.64 16.44 15.08 Senior Buyers Buyers 10.03 13.77 17.84 15.49 9.68 6.26 15.76 14.71 18.14 14.30 14.56 11.04 15.50 14.84 15.04 14.11 48.86 46.09 50.35 45.37 48.35 44.69 Technicians, Specialists, and Assistant Buyers 15.58 14.39 Note: All reported means are statistically significant at the 0.05 level or better. Nonreported means are not statistically significant (or have a statistical significance greater than 0.05). control for cost of living and labor market competitiveness and their effect on salary variance. The median housing value and the median household income were used to measure cost of living and labor market competitiveness, respectively. run for these two populations. The remaining three populations included the heads of purchasing units, supervisors and managers, and buyers. Table 3 lists the results of the multiple regression model for these three populations. All assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity are met for the three models. The result is a multiple regression model with one dependent variable and 12 independent variables. Using the standard of a minimum of 10 responses per predictor, the minimum sample size for each regression model is 120 valid cases. Sample sizes for the senior buyer and technician populations were smaller than 120 cases (89 and 94 valid cases, respectively). Therefore, multiple regression models could not be Gender had a statistically significant effect (a standardized beta of –0.146, –0.165, and –0.135, respectively) on the variance of salaries of heads of purchasing, supervisors and managers, and buyers. For heads of purchasing units, the significant betas were the number of subordinates (0.226), median Table 3 Standardized Beta Values for Predicting Variance in Salaries Heads of Purchasing Units R2: Adj. R2: Iteration Valid N 0.415 0.396 8 251 Female (yes/no) Total years with current employer Total years of experience in purchasing Number of subordinates Number of years of education Hierarchy Annual procurement volume Number of staff in purchasing unit Age Certified (yes/no) Median household income Median housing value Significant beta totals Beta –0.146 0.161 0.117 0.226 0.192 Not sig. Not sig. 0.198 Not sig. Not sig. 0.224 0.145 1.117 0.396 0.375 7 209 % 10 11 8 16 14 0 0 14 0 0 16 10 100 Note: Reported betas are statistically significant at the 0.05 level or better. 894 Public Administration Review • November | December 2006 Supervisors and Managers Beta –0.165 0.166 0.167 0.216 0.249 Not sig. Not sig. Not sig. Not sig. Not sig. 0.304 0.161 1.098 Buyers 0.539 0.52 7 179 % 12% 12% 12 15 17 0 0 0 0 0 21 11 100 Beta –0.135 0.273 0.279 0.193 0.197 –0.153 Not sig. Not sig. Not sig. Not sig. Not sig. 0.461 1.115 % 10 20 20 14 14 –11 0 0 0 0 0 33 100 household income (0.224), number of years of education (0.192), number of staff in the purchasing unit (0.198), total years with current employer (0.161), gender (–0.146), median housing value (0.145), and total years of experience in purchasing (0.117). For purchasing supervisors and materials managers, the significant betas were median household income (0.304), number of years of education (0.249), number of subordinates (0.216), gender (–0.165), total years with current employer (0.166), total years of experience in purchasing (0.167), and median housing value (0.161). For buyers, the significant betas were median housing value (0.461), total years of experience in purchasing (0.279), total years with current employer (0.273), number of years of education (0.197), number of subordinates (0.193), hierarchy (–0.153), and gender (–0.135). Discussion This research is unique in two ways. First, it studies pay inequities within the same occupation and within similar positions. Although respondents were not all working for the same agency, they were all involved in the purchasing occupation in purchasing departments. Furthermore, the analysis was conducted within position level or rank, and it controlled for the human capital characteristics that are often associated with gender pay disparity. Female salaries were consistently lower than male salaries for the position categories covered in this study. However, the challenge that this research undertook was not to confirm that a disparity existed. In previous studies, the wage gap has been as low as $3,665 in a sample of social workers (Koeske and Krowinski 2004) and as high as $17,600 in a sample of private sector purchasing professionals (Fitzgerald 1998). Instead, the challenge was to isolate the effect of gender on pay disparity from the effects of other human capital and cost of living variables. Seniority, experience in field, supervisory responsibilities, education, hierarchy, size of organization, cost of living, labor market competitiveness, and gender were used as predictors of variance in pay. This study found that women and men in similar positions in the same field of work made different salaries for several reasons—one of which is gender. The regression results across positions were similar, with gender significantly contributing to salary for the three populations covered by the regression analysis. In some cases, it was as important as human capital predictors such as experience and job responsibilities. The regression analysis also confirmed that other human capital variables contribute to these disparities. In other words, disparities are driven by human capital and cost of living variables, but they are also driven by the gender of the employee. The predictors included in the three regression models explained 40 percent to 55 percent of the variance in the dependent variable. This means that some of the variance in compensation is driven by factors other than those explored in the literature and used in this article. Human capital variables such as education, years with the current employer, years of experience in purchasing, and the number of subordinates all contributed to the variance in compensation in our sample. Previous studies have inconsistently documented the impact of these differences on men’s and women’s salaries. Some scholars have reported an association between education and salary (e.g., Amirault 1994; Nieva and Gutek 1981), whereas others have not found any significant association (GAO 2003; Stroh, Brett, and Reilly 1992). Holzer (1990) found that years of experience in one’s field plays a role in determining the salaries of individuals, but Koeske and Krowinski (2004) found that experience does not play such a role. In this study, age, certification, hierarchy, annual procurement volume, and number of staff in the unit did not explain the variance in the salaries of individuals. Researchers have reported that age does not significantly affect the wage gap (Bertrand and Hallock 2001; Koeske and Krowinski 2004). Of men and women in purchasing, Fitzgerald (1998) noted that women tend to be younger, less experienced, have fewer supervisory responsibilities, have responsibility for fewer purchasing dollars, are less educated, and hold less senior positions than men. Even when these factors are taken into account, average compensation of women remains lower than that of men. Although the literature inconsistently reports the significance of human capital variables on the wage gap, the wage gap persists. The results of the current study should be interpreted in light of sampling limitations. The first limitation concerns sampling coverage. Individuals not belonging to the National Institute for Governmental Purchasing did not have an opportunity to respond to the survey. However, this is the most comprehensive sampling frame for this population. The NIGP is the largest and only national purchasing organization that has individual members. Individuals automatically become members when their agencies join the NIGP. The survey was sent to the entire sampling frame. The second limitation concerns the response rate. To control for this limitation, we compared key characteristics of the respondents to those of the full sampling frame. There was no indication of any nonresponse bias. Coverage error and nonresponse error should be addressed in all survey research, but scholars recommend that more attention be paid to these two errors in the case of online data collection (Granello and Unequal Pay 895 Wheaton 2004; Bachmann, Elfrink, and Vazzana 1996; Crawford, Couper, and Lamias 2001). As discussed previously, this study took several steps to uncover the existence of sampling bias, and none was discovered. Conclusion Barriers to pay equity are complicated because organizational barriers are interconnected with sociocultural and human capital barriers. Reporting the direct contribution of gender to pay disparity does not relieve policy makers from minimizing these barriers. Although this study held constant the impact of position and agency segregation on pay disparities, forms of segregation remain a serious problem in organizations. Gibelman (2003) has suggested that a multipronged response is needed that would include (1) education and advocacy activities (e.g., to broaden professional and public awareness of the wage gap); (2) group activity (e.g., women working together within and with employers, government, women’s organizations, and unions); (3) professional activity (e.g., collaboration among professional groups to addresses the wage gap); and (4) policy activity (e.g., comparable worth, which seeks to influence position and agency segregation). they may not have an important impact on the labor market. We do not want to shift the debate away from the important policies cited here; rather, we wish to start another front in the “war on wage sexism.” This front must take into consideration that even when women overcome barriers to accessing upper-echelon jobs or traditionally male-dominated occupations, pay disparities are likely to persist. The research in this study did not focus on one government level or one type of government. Instead, it studied purchasing professionals at the state, local, and regional levels. This makes the potential for corrective policy action even more complicated. If the problem were concentrated in one agency, the solution could come from within that agency. However, expecting change to occur from within all of these agencies at once is unrealistic, as many of these agencies may be oblivious to the inequities that exist. In this case, change is needed from outside these organizations. Federal standards must be adopted to specifically address pay inequity at all levels of government and even in the private sector. As we advocate a larger role for federal employment regulation, the federal government seems to be movBetter enforcement of existing laws (e.g., the Equal ing in the opposite direction. There is evidence of a Pay Act and Title VII) and regulations (i.e., affirmabelief that gender-conscious policies are discriminative action), as well as stronger laws (i.e., the Paycheck tory, as signaled in recent executive, judicial, and Fairness Act and Fair Pay Act) are needed to address legislative actions, as well as public opinion. The fedthis issue. Such reforms, however, are unlikely in the eral government appears to be retreating from its role current political climate (Killingsworth 2002). Addiin protecting equal rights. For example, the National tionally, state comparable worth efforts are likely to Council for Research on Women (2004) has continue to encounter barriers. Comparable worth, documented a change in the mission of the U.S. although very important and sorely needed, is not Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau, from a enough to contend with the issues raised in the cur“responsibility to advocate and inform women dirent study. This study has shown that even for people rectly, and the public as well, of women’s rights and who have attained the same positions, although in employment issues” to a “responsibility to promote different organizations, gender continues to play a role profitable employment opportunities for women, to in salary determinations. empower them by enhancing their skills and improving their working conditions, and to provide employResorting to legal action may be ers with more alternatives to effective in dealing with compameet their labor needs.” Absent Resorting to legal action may rable worth within the same from the new mission and vision be effective in dealing with organization or jurisdiction, but is the intention to conduct reit may prove ineffective and search about workplace rights, comparable worth within the impractical because the disparisame organization or jurisdiction, disseminate those findings, and ties revealed in this article can be propose policies that benefit but it may prove ineffective found across different organizaworking women. As a result, and impractical because the tions and jurisdictions. In this more than 25 publications and disparities revealed in this article fact sheets about women’s rights case, class-action lawsuits, which can be found across different tend to have more impact than and employment equity are individual lawsuits, may not be organizations and jurisdictions. no longer distributed by the feasible. Class-action lawsuits are Women’s Bureau. usually based on many employees and one employer (or a few employers). Individual Finally, this study has left some very important wage discrimination cases are very expensive to pursue research questions unanswered. We found that women and difficult to argue. When private cases are won, working in comparable occupations in comparable 896 Public Administration Review • November | December 2006 positions continue to receive lower pay than men. Some of the variables that drive that difference are related to individual skills and cost of living, but gender itself continues to affect salaries. This is an important finding, but unfortunately, it falls short of recommending ways to eliminate the effect of gender on employees’ salaries. Why do men make more money than women even when women break the glass ceiling and many glass walls? This is a compelling research question that needs to be explored. Without some clear answers to this question, these disparities may not be remedied. Frederickson, H. George. 1997. The Spirit of Public Administration. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Gibelman, Margaret. 2003. So How Far Have We Come? Pestilent and Persistent Gender Gap in Pay. Social Work 48(1): 22–32. Gibelman, M., and L. Whiting. 1997. Social Work Salaries and What to Do about Them: A Report to the National Association of Social Workers on Research Gathering and Analysis. Unpublished manuscript, National Association of Social Workers. Granello, Darcy H., and Joe E. Wheaton. 2004. Online Data Collection: Strategies for Research. Journal of Counseling and Development 82(4): References Agron, Joe. 1996. American School and University Compensation Survey. American School and University 68(1): 14–21. Alkadry, Mohamad G., and Beach, Donna T. 2003. Compensation Survey Report. Herndon, VA: National Institute of Governmental Purchasing. Alkadry, Mohamad G., Kimberly Nolf, and Erin Condo. 2002. Pay Equity in West Virginia State Government. Public Affairs Reporter 19(2): 1–6. Amirault, Thomas A. 1994. Job Market Profile of College Graduates in 1992: A Focus on Earnings and Jobs. Occupational Outlook Quarterly 38(1): 2–28. Andrews, Dorine, Blair Nonnecke, and Jennifer Preece. 2003. Electronic Survey Methodology: A Case Study in Reaching Hard-to-Involve Internet Users. Journal of Human-Computer Interaction 16(2): 185–210. Bachmann, Dorine, John Elfrink, and Gary Vazzana. 1996. Tracking the Progress of E-Mail versus Snail Mail. Marketing Research 8(1): 31–35. Becker, Roy. 1961. Study of Salaries of NASW Members. New York: National Association of Social 387–93. Groshen, Erica L. 1991. The Structure of the Female/ Male Wage Differential. Journal of Human Resources 26(3): 457–72. ———. 2001. The Structure of the Female/Male Wage Differential: Is It Who You Are, What You Do, or Where You Work? Journal of Human Resources 26(3): 457–72. Guy, Mary E. 1993. Three Steps Forward, Two Steps Backward: The Status of Women’s Integration into Public Management. Public Administration Review 53(4): 285–92. Heilman, Madeline E., Aaron S. Wallen, Daniella Fuchs, and Melinda M. Tamkins. 2004. Penalties for Success: Reactions to Women Who Succeed at Gender-Typed Tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology 89(3): 416–27. Holzer, Harry J. 1990. The Determinants of Employee Productivity and Earnings. Industrial Relations 29(3): 403–22. Kelly, Rita Mae. 1991. The Gendered Economy: Work, Careers, and Success. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Kelly, Rita Mae, Mary E. Guy, Jayne Bayes, Georgia Workers. Bertrand, Marianne, and Kevin F. Hallock. 2001. The Duerst-Lahti, Lois L. Duke, Mary M. Hale, Cathy Gender Gap in Top Corporate Jobs. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 55(1): 3–21. Blau, Francine D., Marianne A. Ferber, and Anne E. Public Managers in States: A Comparison of Winkler. 2002. The Economics of Women, Men, and Work. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. Budig, Michelle J. 2002. Male Advantage and the Gender Composition of Jobs: Who Rides the Glass Escalator? Social Problems 49(2): 258–77. Cornwell, Christopher, and J. Edward Kellough. 1994. Women and Minorities in Federal Government Agencies: Examining New Evidence from Panel Data. Public Administration Review 54(3): 265–69. Crawford, Scott D., Mick P. Couper, and Mark J. Lamias. 2001. Web Surveys: Perception of Burden. Social Science Computer Review 19(2): 146–62. Fitzgerald, Kevin R. 1998. Top Pay Levels Keep Going Up. Purchasing 25(12): 42–52. Johnson, Amal Kawar, and Jeanie R. Stanley. 1991. Career Advancement by Sex. Public Administration Review 51(5): 402–12. Killingsworth, Mark R. 2002. Comparable Worth and Pay Equity: Recent Developments in the United States. Canadian Public Policy 28: S171–86. Koeske, Gary F., and William J. Krowinski. 2004. Gender-Based Salary Inequity in Social Work: Mediators of Gender’s Effect on Salary. Social Work 49(2): 309–18. Langer, Steven. 2000. Factors Affecting CFO Compensation. Strategic Finance Magazine 81(9): 38–44. Leenders, Michiel R., and Harold E. Fearon. 1997. Purchasing and Supply Management. 11th ed. Boston: McGraw-Hill. Lennon, Mary Clare, and Sarah Rosenfield. 1994. Relative Fairness and the Division of Housework: The Importance of Options. American Journal of Sociology 100(2): 506–31. Unequal Pay 897 898 Lewis, Gregory Burr, and Kyungho Park. 1989. Turnover Rates in Federal White-Collar Employment: Are Women More Likely to Quit Than Men? American Review of Public Administration 18(1): 13–28. Lindner, James R., Tim H. Murphy, and Gary E. Briers. 2001. Handling Nonresponse Error in Social Science Research. Journal of Agricultural Education 42(4): 43–53. Lowi, Theodore J. 1985. The State in Politics: The Relation between Policy and Administration. In Regulatory Policy and the Social Sciences, edited by R. G. Noll, 67–105. Berkeley: University of California Press Mani, Bonnie G. 1997. Gender and the Federal Senior Executive Service: Where Is the Glass Ceiling? Public Personnel Management 26(4): 545–59. Miller, Will, Brinck Kerr, and Margaret Reid. 1999. A National Study of Gender-Based Occupational Orazem, Peter F., and J. Peter Mattila. 1998. MaleFemale Supply to State Government Jobs and Comparable Worth. Journal of Labor Economics 16(1): 95–121. Powell, Gary N. 1988. Women and Men in Management. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Riggs, Fred. 1970. Administrative Reform and Political Responsiveness: A Theory of Dynamic Balancing. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications. Rose, Stephen J., and Heidi I. Hartmann. 2003. Still a Man’s Labor Market: The Long-Term Earnings Gap. Washington, DC: Institute for Women’s Policy Research. www.iwpr.org/pdf/C355.pdf [accessed August 8, 2006]. Rosener, Judy B. 1990. Ways Women Lead. Harvard Business Review 68(6): 119–25. Rumberger, Russell W., and Scott L. Thomas. 1993. The Economic Returns to College Major, Quality and Performance: A Multilevel Analysis of Recent Segregation in Municipal Bureaucracies: Persistence of Glass Walls? Public Administration Review 59(3): 218–30. Morgan, James. 1997. 1997 Salary Survey: From Checkers to Chess. Purchasing 24(12): 36–43. Muller, Eugene W. 1991. An Analysis of the Purchasing Manager’s Position in Private, Public and Nonprofit Settings. International Journal of Purchasing and Materials Management 27(4): 16–23. Naff, Katherine C. 1994. Through the Glass Ceiling: Prospects for the Advancement of Women in the Federal Civil Service. Public Administration Review 54(3): 507–14. National Council for Research on Women. 2004. Missing Information about Women’s Lives. www. ncrw.org/misinfo/index.htm [accessed August 8, 2006]. Newman, Meredith A. 1993. Career Advancement: Does Gender Make a Difference? American Review of Public Administration 23(4): 361–84. ———. 1994. Gender and Lowi’s Thesis: Implications for Career Advancement. Public Administration Review 54(3): 277–84. Nieva, Veronica F., and Barbara A. Gutek. 1981. Women and Work: A Psychological Perspective. New York: Praeger. Noonan, Mary C. 2001. The Impact of Domestic Work on Men’s and Women’s Wages. Journal of Marriage and Family 63(4): 1134–45. Ogden, Jeffrey A., George A. Zsidisin, and Thomas E. Hendrick. 2002. Factors That Influence Chief Purchasing Officer Compensation. Journal of Supply Chain Management 38(3): 30–38. Graduates. Economic of Educational Review 12(1): 1–19. Schiller, Britt Marie 1989. Female–Male Earnings Gap Narrows. Washington Post, August 27. Solomon, Lewis, and Paul Wachtel. 1975. The Effects of Income on Type of College Attended. Sociology of Education 48: 75–90. Stivers, Camilla. 1993. Gender Images and Public Administration: Legitimacy and the Administrative State. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Stroh, Linda, Jeanne Brett, and Ann H. Reilly. 1992. All the Right Stuff: A Comparison of Female and Male Managers’ Career Progression. Journal of Applied Psychology 77(3): 251–60. Thai, Khi V. 2001. Public Procurement Reexamined. Journal of Public Procurement 1(1): 9–50. U.S. Department of Labor, Employment Standards Administration, Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs (OFCCP). 2004. Interpreting Nondiscrimination Requirements of Executive Order 11246 with Respect to Systemic Compensation Discrimination, Notice. Federal Registry 69(220): 67246–52. U.S. General Accounting Office (GAO). 2003. Women Earnings: Work Patterns Partially Explain Difference between Men’s and Women’s Earnings. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. GAO-04-35. www.gao.gov/new.items/ d0435.pdf [accessed August 8, 2006]. Wise, Lois R. 1990. Social Equity in Civil Service Systems. Public Administration Review 50(5): 567–75. Public Administration Review • November | December 2006