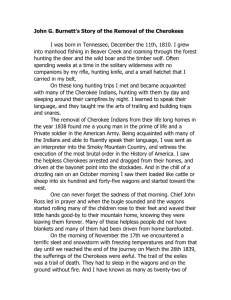

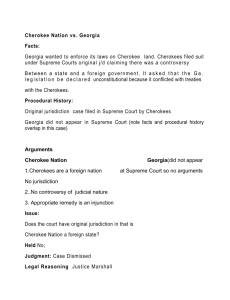

Cherokees, Arkansas, and Removal: 1794-1839 Historic Context

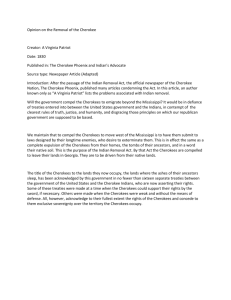

advertisement