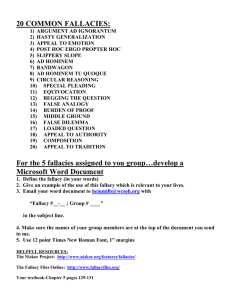

NOTES ON PROPAGANDA. Examples of Propaganda Propaganda is the spread of information or ideas with the purpose of influencing feelings or actions. Propaganda is always biased and can be negative or positive, but usually has a negative connotation. Common Examples of Propaganda Building a mental image - A politician will present an image of what the world would be like with immigration or crime so that the voters will think of that image and believe that voting for him will reduce that threat. Overstating participation - The concept of "Get on the Bandwagon" is appealing to a huge number of people by finding common threads, like religion, race, or vocation. The theme here is "everyone else is doing it, and so should you." Building false images - Presidents try to appear to be "common folks" but they really aren't. Examples are Bill Clinton eating at McDonald's or Ronald Reagan chopping wood. Generating fear - Fear is generated to change people's behavior. An ad will show a bloody accident then remind people to wear their seatbelts. Promising happiness - Selling happiness is a concept used in ads, such as a wellliked actor will explain why you need to buy a product in order to solve a problem. Creating a false dilemma - An example of false dilemma is where two choices are offered as if they are the only two options. For example, a president saying in order to reduce the deficit, we have to either tax the wealthy more or ask seniors to pay more for Medicare. Using slogans - If a slogan is repeated enough times, eventually the public will come to believe it. Appealing to tradition - Good feelings are generated by the thoughts of certain goods and actions, and are frequently included in advertisements such as: "Baseball, apple pie, and Chevrolet." Misquoting - By taking a quote out of context a false impression can be given to the reader or listener. For the film Live Free or Die Hard, Jack Mathews was quoted as saying, "Hysterically...entertaining.". The real quote is, "The action in this fast-paced, hysterically overproduced and surprisingly entertaining film is as realistic as a Road Runner cartoon." Name calling - An example of name calling in propaganda would be: "My opponent is an alcoholic" Assertion - This is presenting a fact without any proof, as in "This is the best cavityfighting toothpaste out there." Propaganda and Wars Propaganda is part of war, both in the past and in current times. Here are examples: In 2013, Iran showed pictures of their new stealth fighter flying over Mount Damavand in Northern Iran. It was soon discovered that it was photoshopped. During the McCarthy Era, mass media tried to convince everyone that Communists were taking over the United States. Alexander the Great intimidated an army by leaving armor and helmets that were very large when they retreated. This made them look like giants. In Vietnam, Americans took Vietnamese fishermen to an island and showed them a resistance group. When they returned, the fishermen told everyone and the Vietnamese spent a lot of time and effort trying to eliminate this fake group. The United States dropped leaflets over Iraq telling people that Saddam Hussein was responsible for their suffering. Generalities in Propaganda Glittering generalities are words that appeal to people on an emotional level and are commonly used in propaganda. Since propaganda is rampant in politics, here is a list of generalities that are used often by politicians: Actively Caring Challenge Change Citizen Commitment Common sense Confident Courage Crusade Dream Duty Family Freedom Hard working Humane Initiative Legacy Liberty Moral Opportunity Passionate Peace Principled Prosperity Protect Proud Reform Rights Share Strength Success Tough Truth Vision https://examples.yourdictionary.com/examples-of-propaganda.html Public Relations and Propaganda Techniques View all blog posts underArticles | View all blog posts underMaster's in Strategic Public Relations Online Propaganda has been an effective tool to shape public opinion and action for centuries. Since propaganda and public relations both share the goal of using mass communication to influence public perception, it can be easy to conflate the two. Propaganda, however, traffics in lies, misinformation, inflammatory language, and other negative communication to achieve an objective related to a cause, goal or political agenda. Though propaganda techniques can be employed by bad actors on the world stage, these same concepts can be utilized by individuals in their interpersonal relationships. Regardless of how propaganda is employed, these common techniques are used to manipulate others to act or respond in the way that the propagandist desires. Bandwagon The desire to fit in with peers has long been recognized as a powerful force in society. Propagandists can exploit this longing by using the bandwagon technique to appeal to the public. This common propaganda technique is used to convince the public to think, speak, or act in a particular way simply because others are. The public is invited to “jump on the bandwagon” and not be left behind or left out as the rest of society engages in what they perceive to be correct behavior. Snob Appeal In an attempt to appeal to the general public’s aspiration to belong to society’s high class, propagandists can use snob appeal as a selling technique. This technique involves convincing the public to behave in ways that are agreeable to the propagandists and serve their purposes. In order for this technique to be successful, propagandists have to first position themselves as having a product, idea or opinion that is worthy of elite status. Many publicists in charge of public relations for companies employ a similar technique as a way to maintain the perception that the business creates and sells highquality goods. Vague Terms Propagandists sometimes achieve their goal of swaying public opinion simply by using empty words. When employing this technique, propagandists will deliberately use vague terms meant to entice. Examination of the terms, however, can reveal that they offer no real definition or commitment to meaning. The goal of this type of propaganda can be to offer generalities that provoke audiences to expend their energy on interpretation rather than critiquing. Loaded Words Words have power when it comes to public relations, and it’s no surprise that many propagandists use a technique involving loaded words to sway public opinion. When attempting to convince the public to act, propagandists may use excessively positive words or those with agreeable associations. If the goal is to hinder action, propagandists can select words that are highly negative to communicate with the public such as those that inspire fear, anger, or doubt. A simple and effective means of loaded words usage is the act of name-calling, which many political groups have used to disparage opposition, quell dissent. and scapegoat groups of people. Transfer Propagandists may attempt to associate two unrelated concepts or items in an effort to push what they’re selling to the public. With the technique of transfer, propagandists conjure up either positive or negative images, connect them to an unrelated concept or item, and try to move the public to take action. Commonly, propagandists can associate the glory or virtue of a historical event with their product or the action that they want the public to take. Conversely, transfer can also be employed as a means to convince the public to not take an action, lest they suffer a disagreeable fate. Unreliable Testimonial Propaganda can hinge on the ability of an unrelated person to successfully sell an idea, opinion, product, or action. In modern day advertising, companies may enlist celebrities to help sell their products as part of their public relations efforts. Oftentimes, these celebrities don’t have any personal experience with the products or background with the science utilized to create them, but their testimonial can increase sales simply because they provide a recognizable and sometimes trustworthy face to the public. Viewers of this type of propaganda put their faith in the testimonial rather than judging the product, idea, or company on its own merits. Recommended Reading What is Public Relations? The Latest Trends in Public Relations Practice George Washington University Public Relations Program Sources How Propaganda Works Propaganda Examples With Videos Types of Propaganda (PDF) Propaganda Techniques (PDF) Fallacies and Propaganda False Reasoning and Propaganda Techniques (PDF) Devices Used in Propaganda Propaganda Throughout History College of DuPage’s List of Propaganda Techniques Spotting Propaganda (PDF) Advertising Techniques 5 Most Common Advertising Techniques Public Service Advertising and Propaganda Rhetoric in Advertising: Propaganda Plain Folks Examples of Bandwagon in Literary Works Propaganda Techniques in Modern Society and Animal Farm 12 Classic Propaganda Techniques Narcissists Use to Manipulate You German Propaganda Archive WWII Propaganda Soviet Propaganda Posters Master’s in Strategic Public Relations Online https://gspm.online.gwu.edu/blog/public-relations-and-propaganda-techniques/ FALLACIES and PROPAGANDA It is important to be able to evaluate what you read and hear. If you did not sort the credible from the incredible, the serious from the playful, the essential from the nonessential, the world would be full of conflicting and bewildering messages. Critical thinking enables you to distinguish between fact and opinion and distinguish sound from faulty reasoning. One kind of faulty reasoning is a fallacy, a breakdown of logic. A fallacious argument is one that tries to argue from A to B, but because it contains hidden assumptions or factual irrelevancies, reaches an invalid conclusion. Another kind of faulty reasoning results from substituting emotion for thought. Propaganda is an indirect message appealing primarily to emotion. It is aimed at forming opinions rather than increasing knowledge. Propaganda intends to persuade without offering a logical reason to adopt a particular view or take a particular action. While the word itself carries rather a negative connotation (implying intent to mislead or deceive) the techniques can be used in good causes as well—a Cancer Society fundraiser, for example. At least some propaganda techniques are used occasionally by non-profit organizations, advertisers, churches, news organizations, governments, and instructors. For good or ill, makers of propaganda typically select facts most appropriate to their purpose and omit facts that do not help them achieve that purpose. Because some propaganda uses facts (albeit selectively), it can look like a reasoned argument. But because it fails to make a logical case, propaganda is often fallacious as well as emotional. Fallacies and propaganda devices are slippery by nature; they overlap, are often used in combination, and do not always fit neatly into one category or another. Following are examples. Ad Hominem Fallacy An ad hominem fallacy redirects the discussion of an issue to a discussion of one of the subjects—to his or her personal failings, inconsistency, or bias. For example, in a discussion of the pros and cons of privatizing Social Security, it would be an ad hominem attack simply to declare your opponent a parasite feeding on the lifeblood of the working class. Similarly, you would be guilty of an ad hominem attack if you exclaimed, “How can you claim to be a born-again Christian?” (pointing out an inconsistency of position) or “Of course you would say that—you’re a Libertarian!” (pointing out personal bias). None of these response addresses the actual pros and cons of the proposal to privatize Social Security. A preemptive ad hominem attack, launched before the discussion fairly begins, is called “Poisoning the Well” (below). Ad Nauseum Fallacy Hitler’s Propaganda Minister, Joseph Goebbels, said that if only you repeat something often enough, people will come to believe it. Ad nauseum repetition is the stuff urban legends are made of. Less harmless than urban legends is the indoctrination (“brainwashing”) of cult groups, which aims to create belief by aiming sheer, ad nauseum repetition relentlessly at an exhausted subject. Fallacy Based on Appeal to Belief, Common Practice, or Expertise An appeal to belief suggests that, since most reasonable people (of your sort) believe something, you should believe it, too. “Educators fear that vouchers will undermine funding for public schools.” Educators in particular might be inclined to conclude that this fear is universal among educators, and identify with the belief because they identify with the group. Appeals to common practice suggest that most everyone does it, and furthermore that it is therefore okay; “Nobody in California comes to a full stop. That’s why they call it ‘the California Stop.’” An appeal to expertise dares you to pit your own ignorance against experts making a value claim (a Grammy award-winning country singer publicly endorses a political candidate, for example). Now, specialists agreeing on objective claims about matters within their field of expertise are reasonably to be believed, but specialists making value judgments outside their field might not. (For more, see the TIP Sheet “Objective and Subjective Claims.”) Phrases like the following might signal an appeal to belief, expertise, or common practice: “Ask anyone…” “Everyone knows…” “Any reasonable person would…” “It’s obvious that…” Fallacy Based on Appeal to Indignation or Anger The problem with the appeal to indignation or anger is that anger is a poor substitute for reasoning. On the contrary, anger clouds thinking. Certainly anger is sometimes justified, when it follows an argument that gives me grounds for anger, but anger is not the way to reach that conclusion. And anyway, sometimes we are angry for irrational reasons. For example: “The governor is cutting education funds!” may cause a reaction of anger, followed by the conclusion, “The governor is a dolt and a fascist!” (see “Name-Calling,” below). Anger short-circuits the reasoning process, whereby we might have examined the figures and learned (much to our surprise) that education funding is up from last year—just not up as much as originally hoped. Fallacy Based on Appeal to Pity Who has not seen the heartbreaking pictures of starving orphans with the request for donations to ease their plight? A valid appeal to pity has a direct link between the object of pity (starving children) and the desired action (the money that can help feed them). Appeal to pity becomes a fallacy when there is no logical link between the arousal of pity and the desired action: “Please give me a break, Professor. If I don’t pass this class I’ll lose my financial aid.” Whether this student is qualified to pass the class depends on the quality and quantity of work completed, not on financial need. There is no relevant connection between the student’s need on the one hand, and the quality of work she has (or has not) performed on the other. Fallacy Based on Appeal to Popularity or Bandwagon Appeal to popularity exploits the human desire to belong to a group. While there is nothing wrong with belonging to a group, some decisions are not group decisions, should be made without taking a head count, and should be held to even if they are unpopular. For example, my softball team’s consensus should probably not be the determining factor in my decision to take a cut in pay in return for more flexibility in my working hours. My softball team’s disapproval (they think I should go for the higher salary) should be irrelevant. “Jumping on the bandwagon” is supporting a cause or position merely because it appears to be popular or winning. Politicians who waver from one position to another are sometimes trying to protect their jobs by appealing to the greatest number of voters based on changing poll information. Of course, it is reasonable sometimes to change one’s mind; it is just usually preferable to base the change on reason. Fallacy Based on Appeal to Ridicule Sarcasm is always hostile. Ridicule, sarcasm, and the “horse laugh” are the persuasion techniques of bullies. Appeal to ridicule tries to convince you to accept an argument in order to avoid becoming the butt of the joke. The laugh might be at the person (see “Ad Hominem,” above) or at his position (see “Straw Man,” below). Whether it is blatant or subtle, ridicule essentially denies discussion. Apple Polishing Fallacy Apple polishing is connecting compliments to unrelated issues. It urges someone to accept a claim in the afterglow of pleasure at the compliment. “You are by far the best math teacher I’ve ever had. You made me love math! I think I may change my major to math. I want to be just like you. Oh—I haven’t finished that chapter review; you don’t mind if I hand it in late?” Fallacy Based on Begging the Question Begging the question is a type of circular reasoning that presents as a true premise an assertion that actually requires its own proof. This leads to a “conclusion” that has already been pre-supposed or implied. For example, a student complains bitterly that he failed the English composition exit exam. “The test is bogus! I’ve taken it twice now, and they won’t pass me!” The student concludes that the test is bogus. His implied premise is that his essay is, in fact, good enough to pass. But whether his essay is good enough to pass is, itself, the question. Asserting that it is (or implying that it is) is not sufficient to prove that it is. (Application of the test rubric, by trained test scorers—twice—would appear to conclude that it is not.) Distribution Fallacies: Composition and Division Distribution fallacies arise two ways: In the composition fallacy, I know the characteristics of the whole, and (wrongly) attribute those characteristics to each of its parts. Stereotyping of individuals may result from a composition fallacy. Suppose I have read statistics that attribute very strong business ambition to a certain demographic group. I then attribute business ambition to each person of that group, without respect for individual variations (See also “Hasty Generalization,” below). In its converse, the division fallacy, I know the characteristics of an individual or part, and (wrongly) attribute those characteristics to the whole. However, the parts are not necessarily representative of the whole. Broad stereotyping of a group may result from the division fallacy. Suppose I have become acquainted with a man from Taiwan who is an extremely talented electrical engineer. I mistakenly conclude that all Taiwanese, as a group, are amazing electrical engineers. False Dilemma Fallacy The false dilemma fallacy limits responses to those which serve the ends of its user (“Yes or no?”), implicitly denying the middle ground (“Maybe…”) or any qualified response (“Yes, but…”) . In a discussion on illegal immigration from Mexico to the U.S., for example, there is a vast middle ground of discussion between the extremes of building a very high fence on the one hand, and allowing uncontrolled immigration with its associated high social costs on the other. To suggest that a discussion on immigration is simply a choice between the two extremes is a false dilemma. Political surveys frequently pose questions positing false dilemmas, using loaded questions that are worded in such a way that the desired attitude is suggested in the question. The responder is thus “steered” toward the desired response. Guilt by Association Fallacy The guilt by association fallacy muddles the process of fairly evaluating an idea, person, or group by interjecting irrelevant and misleading negative material. Think of it as a kind of red herring (below). This fallacy tries to connect ideas or persons to something unsavory or untrustworthy in order to discredit them. Take, for example, this claim made by an individual running against the incumbent for the office of sheriff: “Our sheriff has breakfast every single week with the head of a white supremacist group.” The fact that this weekly breakfast is attended by thirty-five local businessmen, including the head of the white supremacist group, is selectively omitted here (See also “Stacking the Deck, below). Be on guard when you see phrases like these: “has ties to…” “connected with” “is the parent company/subsidiary of…” “was a member of…” Hasty Generalization Fallacy A hasty generalization draws an unwarranted conclusion from insufficient evidence (see also “Distribution fallacies,” above). It often happens when the sample is too small to support the conclusion. For example, data compiled from 1,000 households, all in Nebraska, would probably be insufficient to accurately predict the outcome of a national election. Hasty generalization occurs, as well, when the sample is too biased to support the conclusion: Ten million households, selected from all fifty states, but all of them Libertarian (or Democrat, or Republican), may also be insufficient to predict the result of a national election. Another kind of hasty generalization occurs as the result of misleading vividness. For example, a man in Tonga who watched many American daytime dramas (“soap operas”) might conclude that people in the U.S. were more materially prosperous, more well-dressed, more vicious, more self-centered, and more immodest than most of them are. Name Calling Name-calling is not so much a fallacy (see “Ad hominem,” above) as it is a propaganda technique, a crude attempt to make mud stick. It does not pretend to thoughtfully address issues or prove anything. “The femi-Nazis want to eliminate gender.” “We don’t need any more right-wing theocrats (or leftist, activist judges) on the bench.” “This administration is a bunch of lying, neo-Fascist colonialists (or liberal, atheistic social engineers).” “America is the Great Satan.” Negative Proof Fallacy or Argument from Ignorance The negative proof fallacy declares that, because no evidence has been produced, that therefore none exists. For example, a theist might declare, “You atheists cannot prove God does not exist, therefore God exists.” On the other hand, the atheist declares, “You deists cannot prove that God exists, therefore God does not exist.” First of all, the lack of proof one way or the other does nothing to prove or disprove God’s existence; the deist and the atheist may just as well make simple assertions: “God exists,” and “God does not exit.” Second, the general rule is that the person who asserts something has the burden of proof to provide evidence to support that something. It is not sufficient to make the assertion and then shift the burden of proof to the listener to prove you wrong. Poisoning the Well Fallacy Poisoning the well is an ad hominem attack (see “Ad hominem,” above) on a person’s integrity or intelligence that takes place before the merits of a case can be considered. It redirects a discussion to the faults of one of the parties. “Of course she will oppose the tort reform bill—she’s a lawyer, isn’t she?” The speaker suggests that something (greed? law school?) has corrupted the lawyer’s thinking to a degree that she cannot evaluate the tort reform bill on its own merits. Now the discussion is no longer about the merits of the tort reform bill at all, but about the personal qualities and motives of the other party. Questionable Cause Fallacy A questionable cause fallacy is the result of incorrectly identifying the causes of events either by oversimplifying or by mistaking a statistical correlation for a cause. Oversimplifying occurs when complex events with many contributing causes are attributed to a single cause: “School shootings happen because bullying makes students ‘snap.’” Since at least some bullied students do not shoot their classmates, this would appear to be oversimplified. Mistaking correlation for cause can happen when unrelated events occur together, either by chance or because they are actually both results of yet another cause. For example, does eating more ice cream in the summer cause an increase in crime rates? The rates for ice cream eating and violent crime both rise each summer. However, the statistical correlation notwithstanding, eating ice cream does not cause violent crime to increase. Rather, ice cream eating and crime may rise together as a result of a common cause—hot weather. There may be an evolutionary advantage to discerning cause and effect; we’re hard-wired to look for causes, even if wrongheadedly. The tendency for humans to “see” a pattern where none exists is called the clustering illusion, demonstrated by the Texas sharpshooter fallacy: The Texas sharpshooter fires a hundred shots randomly into the side of barn. He then paints a target around the thickest cluster of holes. He has taken statistically non-significant, random data and attributed to it a common cause. The perennial attempts to find meaningful, hidden codes in the works of Shakespeare or the Bible (or the works of Leonardo da Vinci) illustrate the clustering illusion. Fallacy Based on Scare Tactics or Appeal to Fear Scare tactics create appeal from emotion. For example, the following appeal to fear requires me to accept a certain standard of “businesslike” attitude and behavior on grounds of fear: This company expects a high level of commitment; be here in the office finishing the proposal through the weekend. Don’t forget your employee review is Monday. Whether we can agree on what an acceptably “high level of commitment” is will have to wait for another time, since my immediate problem is avoiding the implied threat of a poor employee review. A warning differs from scare tactics because a warning is relevant to the issue. For example, it would be foolish to ignore the following warning: No late research papers will be accepted; you cannot pass the class without a passing grade on this paper. Slippery Slope Fallacy Slippery slope arguments conclude that, if an eventual, logical result of an action or position is bad, then the original action or position must be bad. It is characteristic of a slippery slope argument that the final badness arrives in increments; thus, even though the badness could have been foreseen and may even have been inevitable, most of us are taken by surprise. Slippery slope arguments are common in social change issues. A slippery slope argument is not necessarily a fallacy. It becomes a fallacy when the chain of cause and effect breaks down. If I cannot show you the reason why a causes b, and b causes c, and c causes d, my argument is fallacious. Typically, the (fallacious) chain of “logical” intermediate events becomes improbably long and unlikely, exponentially increasing the unlikelihood of the final result. Often a historical precedent is cited as evidence that the chain of increasingly bad effects will occur. For example, there exist several historical precedents for the confiscation of guns by oppressive governments: in both Marxist and Nazi states, for example, the government confiscated the guns of citizens based on the registration records of those guns. Gun aficionados in the U.S. argue that gun registration anywhere will inevitably lead to confiscation of guns by the government. However, as a simple matter of logic, a historical precedent alone does not make those results necessary (or even probable) in every case. Gun registration opponents could avoid the slippery slope fallacy if they could show the reason why registration leads inevitably to confiscation. Or, if gun registration opponents could demonstrate that the principle that favors registration of guns is the same principle that would allow confiscation of guns, the fallacy may be avoided. Smokescreen or Red Herring Fallacy The smokescreen fallacy responds to a challenge by bringing up another topic. Smokescreen or red herring fallacies mislead with irrelevant (though possibly related) facts: “We know we need to make cuts in the state budget. But do you really think we should cut funds for elementary physical education programs?” “Well, we have to cut something. This governor has turned a million-dollar surplus into a billion-dollar shortfall. And what’s up with that shady software deal he made?” Why red herring? A herring (a salt-cured fish) has a very strong odor; drag one across the trail of an animal and tracking dogs will abandon the animal’s scent for the herring’s. (A satirical fictitious example is the “Chewbacca Defense,” first used on the television show South Park in 1998, in which a lawyer convinces a jury to convict (and later to acquit) by misleading them with irrelevant facts about Wookies; for more information, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chewbacca_Defense.) Stacking the Deck Fallacy Stacking the deck is a fallacy of omitting evidence that does not support your position. Like the card shark who “stacks” the cards before dealing to favor his own hand, a person who stacks the deck of an argument is cheating. All the cards favor him, because he has arranged them so. On the contrary, honest treatment of a discussable issue should evaluate evidence both for and against one’s own position. Stacking the deck can achieve short term wins against the unwary, but eventually a card stacker’s credibility will suffer. For example, look again at the claim made above (see “Guilt by Association”) by the person running against an incumbent for the office of sheriff: “Our sheriff has breakfast every single week with the head of a white supremacist group.” This assertion might win the challenger some votes; note that the incumbent cannot truthfully deny it and independent investigation would confirm it. However, the challenger has selectively omitted the fact that this weekly breakfast is attended by thirty-five local businessmen, including the head of the white supremacist group. Should someone effectively expose the cheat before the election, the challenger will appear in an unfavorable light. Straw Man Fallacy If I take a complex position and oversimplify it in order to more easily overcome it, I am guilty of the straw man fallacy. In a sense, a straw man fallacy is a type of red herring (above), in that it misleads by misrepresenting the opponent’s position. Complex ideas about family planning are misrepresented below: “The nuns taught us family planning was a sin. We would have to keep having babies because babies were a blessing, no matter how many of them already were in the house.” The speaker may go on to demonstrate how unnatural and medieval such ideas are, defeating the straw man he himself has created. Instead of defeating his opponent’s best argument, he takes a weak argument, falsifies it, and then “overcomes” it. Political parties often demonize each other, painting extreme caricatures of each other’s actual, more thoughtful, positions in order to argue more easily (in marketable sound-bites) against them. The straw man fallacy works best if the characterization closely resembles the real one; that is, if I choose to misrepresent your position, I should not be too obvious about it. Subjectivist or Relativist Fallacy The subjectivist or relativist fallacy turns all disagreements into matters of opinion by claiming that what is true and what is false are different for different people. In matters of fact, such a claim cannot be made without making nonsense. In matters of opinion, however, there exists no single standard to prove one or another claim conclusively true or false. The rightness or wrongness of either opinion might very well depend on where you stand. But even for matters of opinion, if there is no “truth,” then any opinion seems as good as any another and all opinions seem essentially groundless and equally meaningless. On the contrary, it is a virtue of a “good” opinion that it has a basis in evidence and logic. For more, see the TIP Sheets “Objective and Subjective Claims” and “Deductive, Inductive, and Abductive Reasoning.” A subjectivist fallacy on a factual matter puts an end to rational discussion: A: “The earth is roughly spherical, and goes once around the sun in about 365 days. B: “That may be true for you, but it’s not true for me. And I have a right to my opinion.” But a subjectivist claim even on a subjective matter (“It may be wrong for you, but it’s right for me!”) makes further discussion difficult by eliminating the common ground for discussion. Fallacy Based on Transfer Transfer is an emotional appeal that associates something or someone known (and therefore implied “good”) with a product, idea, or candidate. Celebrity endorsements are an example. Well-known objects and images can be used the same way, evoking an emotional response that sponsors hope will transfer to their cause. For example, images of Arlington National Cemetery might be used to help raise money for veterans’ groups. The image of Mount Everest is often used to help sell outdoor products (though relatively few of the products’ users will ever actually attempt to climb Everest). Wishful Thinking Fallacy Wishful thinking is choosing to believe something is true because we really, really want it to be true. We usually perpetrate wishful think on ourselves, but it also underlies many “positive thinking” philosophies: to believe in your dream is to make it come true. Though wishful (positive) thinking followed by action may help me achieve my goals, wishful thinking alone achieves nothing. Wishful thinking promotes comfort, but it does not promote reasoning. http://www.butte.edu/departments/cas/tipsheets/thinking/fallacies.html http://csmt.uchicago.edu/glossary2004/propaganda.htm