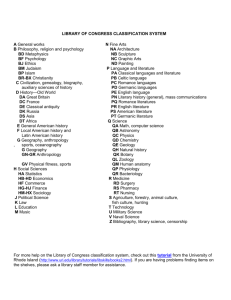

Germanic Languages: History, Characteristics, and Classification

advertisement