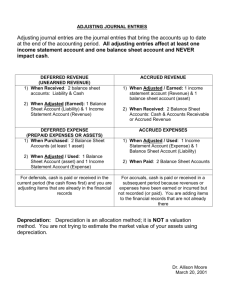

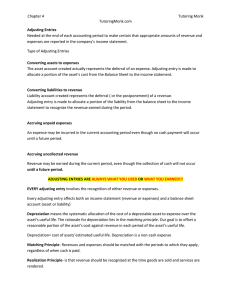

Chapter 4 The Accounting Cycle: Accruals and Deferrals Copyright © 2018 McGraw-Hill Education. All rights reserved. No reproduction or distribution without the prior written consent of McGraw-Hill Education. 4-1 Introduction In Chapter 3, you learned that we record revenue when it is earned. For example, when a hairdresser cuts a customer’s hair, revenue is earned when the hair is cut and the fee is collected. Suppose the same passenger boards a Carnival Corporation cruise ship to the Bahamas using a ticket that was purchased six months in advance. At what point should the cruise line recognize that ticket revenue has been earned? 4-2 Introduction: Carnival Corporation In its balance sheet, Carnival Corporation reports a $3.3 billion liability account called Customer Deposits. As passengers purchase tickets in advance, Carnival Corporation credits the Customer Deposits account for an amount equal to the cash it receives. It is not until passengers actually use their tickets that the company reduces this liability account and records Passenger Ticket Revenue in its income statement. 4-3 Timing Differences For most companies, revenue is not always earned as cash is received, nor is an expense necessarily incurred as cash is disbursed. Timing differences between cash flows and the recognition of revenue and expenses are referred to as accruals and deferrals. In this chapter, we examine how accounting information must be adjusted for accruals and deferrals prior to the preparation of financial statements. 4-4 Step 4 in the Accounting Cycle We covered the first three steps of the accounting cycle in Chapter 3: ◦ Recording transactions ◦ Posting transactions ◦ Preparing a trial balance KEY POINT In this chapter, we focus solely upon the fourth step of the accounting cycle—performing the end-of-period adjustments required to measure business income. 4-5 The Need for Adjusting Entries Certain transactions affect the revenue or expenses of two or more accounting periods. Adjusting entries are needed at the end of each accounting period to make certain that appropriate amounts or revenue and expense are reported in the company’s income statement. 4-6 Categories of Adjusting Entries Most adjusting entries fall into one of four general categories: 1. Converting assets to expenses. 2. Converting liabilities to revenue. 3. Accruing unpaid expenses. 4. Accruing uncollected revenue. 4-7 Introduction: Converting Assets to Expenses A cash expenditure (or cost) that will benefit more than one accounting period usually is recorded by debiting an asset account (for example, Supplies, Unexpired Insurance, and so on) and by crediting Cash. The asset account created actually represents the deferral (or the postponement) of an expense. In each future period that benefits from the use of this asset, an adjusting entry is made to allocate a portion of the asset’s cost from the balance sheet to the income statement as an expense. This adjusting entry is recorded by debiting the appropriate expense account (for example, Supplies Expense or Insurance Expense) and crediting the related asset account (for example, Supplies or Unexpired Insurance). 4-8 Introduction: Converting Liabilities to Revenue A business may collect cash in advance for services to be rendered in future accounting periods. Transactions of this nature are usually recorded by debiting Cash and by crediting a liability account (typically called Unearned Revenue or Customer Deposits). Here, the liability account created represents the deferral (or the postponement) of a revenue. In the period that services are actually rendered (or that goods are sold), an adjusting entry is made to allocate a portion of the liability from the balance sheet to the income statement to recognize the revenue earned during the period. The adjusting entry is recorded by debiting the liability (Unearned Revenue or Customer Deposits) and by crediting Revenue Earned (or a similar account) for the value of the services. 4-9 Introduction: Accruing Unpaid Expenses An expense may be incurred in the current accounting period even though no cash payment will occur until a future period. These accrued expenses are recorded by an adjusting entry made at the end of each accounting period. The adjusting entry is recorded by debiting the appropriate expense account (for example, Interest Expense or Salary Expense) and by crediting the related liability (for example, Interest Payable or Salaries Payable). 4-10 Introduction: Accruing Uncollected Revenue Revenue may be earned (or accrued) during the current period, even though the collection of cash will not occur until a future period. Unrecorded earned revenue, for which no cash has been received, requires an adjusting entry at the end of the accounting period. The adjusting entry is recorded by debiting the appropriate asset (for example, Accounts Receivable or Interest Receivable) and by crediting the appropriate revenue account (for example, Service Revenue Earned or Interest Earned). 4-11 Adjusting Entries and Timing Differences In an accrual accounting system, there are often timing differences between cash flows and the recognition of expenses or revenue. A company can pay cash in advance of incurring certain expenses or receive cash before revenue has been earned. Likewise, it can incur certain expenses before paying any cash or it can earn revenue before any cash is received. 4-12 Adjusting Entries and Timing Differences (cont.) These timing differences, and the adjusting entries that result from them, are summarized as follows. ◦ Adjusting entries to convert assets to expenses result from cash being paid prior to an expense being incurred. ◦ Adjusting entries to convert liabilities to revenue result from cash being received prior to revenue being earned. ◦ Adjusting entries to accrue unpaid expenses result from expenses being incurred before cash is paid. ◦ Adjusting entries to accrue uncollected revenue result from revenue being earned before cash is received. 4-13 Adjusting Entries Adjusting entries are needed whenever revenue or expenses affect more than one accounting period. Every adjusting entry involves a change in either a revenue or expense and an asset or liability. 4-14 Converting Assets to Expenses End of Current Period Prior Periods Transaction Pay cash in advance of incurring expense (creates an asset) Current Period Future Periods Adjusting Entry Recognizes portion of asset consumed as expenses, and Reduces balance of asset account 4-15 Example: Insurance Policy $18,000 Insurance Policy Coverage for 12 Months $1,500 Monthly Insurance Expense Mar. 1 Feb.28 On March 1, Overnight Auto Service purchased a one-year insurance policy for $18,000. 4-16 Insurance Policy: Initial Entry Initially, costs that benefit more than one accounting period are recorded as assets. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Mar. Account Titles and Explanation 1 Unexpired Insurance Cash P R Debit Credit 18,000 18,000 Purchased a one-year insurance policy. 4-17 Insurance: Adjusting Entry The costs are expensed as they are used to generate revenue. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation Debit Credit Monthly Adjusting Entry for Insurance Mar. 31 Insurance Expense 1,500 Unexpired Insurance 1,500 Adjusting entry to record insurance expense for March. 4-18 Insurance: Financial Statement Impact Balance Sheet Cost of assets that benefit future periods. Income Statement Cost of assets used this period to generate revenue. Unexpired Insurance 3/1 18,000 3/31 1,500 Bal. 16,500 Insurance Expense 3/31 1,500 4-19 Your Turn: Insurance You as a Car Owner Car owners typically pay insurance premiums six months in advance. Assume that you recently paid your six-month premium of $600 on February 1 (for coverage through July 31). On March 31, you decide to switch insurance companies.You call your existing agent and ask that your policy be canceled. Are you entitled to a refund? If so, why, and how much will it be? 4-20 The Concept of Depreciation Depreciation is the systematic allocation of the cost of a depreciable asset to expense. Fixed Asset (debit) On date when initial payment is made . . . Cash (credit) The asset’s usefulness is partially consumed during the period. Depreciation Expense (debit) At the end of the period . . . Accumulated Depreciation (credit) 4-21 Depreciation Is Only an Estimate On Jan. 22, 2018, Overnight Auto Service purchased a building with a useful life of 240 months for $36,000. Using the straight-line method, calculate the monthly depreciation expense. Depreciation Cost of the asset expense (per = Estimated useful life period) $36,000 = $150/month 240 4-22 Case in Point How long does a building last? For purposes of computing depreciation expense, most companies estimate about 30 or 40 years.Yet the Empire State Building was built in 1931, and it’s not likely to be torn down anytime soon. As you might guess, it often is difficult to estimate in advance just how long depreciable assets may remain in use. 4-23 Example: Depreciation Expense Overnight Auto Service would make the following adjusting entry. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation Feb. 28 Depreciation Expense: Building Accumulated Depreciation: Building P R Debit Credit 150 150 To record one month's depreciation. Contra-asset 4-24 Example 2: Depreciation Expense Overnight depreciates its $12,000 of tools and equipment over 60 months. Calculate monthly depreciation and make the journal entry. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation P R Debit Feb. 28 Depreciation Expense: Tools and Equipment Credit 200 Accumulated Depreciation: Tools and Equipment 200 To record one month's depreciation. $12,00060 months = $200 per month 4-25 Computing Book Value for Assets We will assume that Overnight did not record any depreciation expense in January because it operated for only a small part of the month. December 31, 2018 Balance Sheet Presentation Building $ 36,000 Less: Accum. depr. 1,650 Tool and Equipment $ 18,000 Less: Accum. depr. 2,200 34,350 15,800 Cost − Accumulated Depreciation = Book Value 4-26 Converting Liabilities to Revenue End of Current Period Prior Periods Transaction Collect cash in advance of earning revenue (creates a liability) Current Period Future Periods Adjusting Entry Recognizes portion earned as revenue, and Reduces balance of liability account 4-27 Example: Rental Revenue $3,000 Rental Contract Coverage for 3 Months $1,000 Monthly Rental Revenue Dec. 1 Feb. 28 On December 1, Overnight received $3,000 in advance for a three-month rental contract. 4-28 Rental Revenue: Initial Entry Initially, revenues that benefit more than one accounting period are recorded as liabilities. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation Dec. 1 Cash Unearned Rent Revenue Debit Credit 3,000 3,000 Collected $3,000 in advance for rent. 4-29 Rental Revenue: Adjusting Entry Over time, the revenue is recognized as it is earned. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation P R Debit Credit Monthly Adjusting Entry for Rent Revenue Dec. 31 Unearned Rent Revenue 1,000 Rental Revenue 1,000 Adjusting entry to record rental revenue for December. 4-30 Rental Revenue: Financial Statement Impact Balance Sheet Liability for future periods. Unearned Rental Revenue 12/31 1,000 12/1 3,000 Bal. 2,000 Income Statement Revenue earned this period. Rental Revenue 12/31 1,000 4-31 Accruing Unpaid Expenses End of Current Period Prior Periods Current Period Adjusting Entry Recognizes expenses incurred, and Records liability for future payment Future Periods Transaction Pay cash in settlement of liability. 4-32 Example: Wages Owed $1,950 Wages Expense Monday, Dec. 30 Friday, Jan. 3 Tuesday, Dec. 31 On Dec. 31, Overnight owes wages of $1,950. Payday is Friday, Jan. 3. 4-33 Wages Owed: Initial Entry Initially, an expense and a liability are recorded. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation Dec. 31 Wages Expense P R Debit Credit 1,950 Wages Payable 1,950 Adjusting entry to accrue wages owed to employees. 4-34 Wages Owed: Financial Statement Impact Balance Sheet Liability to be paid in a future period. Wages Payable 12/31 3,000 Income Statement Cost incurred this period to generate revenue. Wages Expense 12/31 1,950 4-35 Wage Expense Calculation $2,397 Weekly Wages $1,950 Wages Expense Monday, Dec. 30 Tuesday, Dec. 31 $447 Wages Expense Friday, Jan. 3 Let’s look at the entry for Jan. 3. 4-36 Wages Owed: Payment Entry The liability is extinguished when the debt is paid. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation Jan. 3 Wages Expense (for Jan.) Wages Payable (accrued in Dec.) Cash P R Debit Credit 447 1,950 2,397 Weekly payroll for Dec. 30–Jan. 3. 4-37 Accruing Uncollected Revenue End of Current Period Prior Periods Current Period Adjusting Entry Recognizes revenue earned but not yet recorded, and Records receivable Future Periods Transaction Collect cash in settlement of receivable 4-38 Example: Service Revenue $750 Repair Service Revenue Dec. 15 Dec. 31 Jan. 15 On Dec. 31, Airport Shuttle Service owes Overnight half of its maintenance agreement. The one-month fee of $1,500 is to be paid on the 15th day of January. 4-39 Accrued Service Revenue Entry Initially, the revenue is recognized and a receivable is created. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation P R Debit Dec. 31 Accounts Receivable Repair Service Revenue Credit 750 750 Adjusting entry to record accrued service revenue. 4-40 Accrued Revenue: Financial Statement Impact Balance Sheet Receivable to be collected in a future period. Accounts Receivable 12/31 750 Income Statement Revenue earned this period. Repair Service Revenue 12/31 750 4-41 Accrued Revenue Calculation $1,500 Total Revenue $750 Service Revenue Dec. 15 $750 Service Revenue Dec. 31 Jan. 15 Let’s look at the entry for January 15. 4-42 Accrued Revenue: Collection Entry The receivable is collected in a future period. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation P R Debit Jan. 15 Cash Credit 1,500 Repair Service Revenue (for Jan.) 750 Accounts Receivable (accrued Dec. 31) 750 To record cash collected for monthly maintenance fee. 4-43 Accruing Income Taxes Expense: The Final Adjusting Entry As a corporation earns taxable income, it incurs income taxes expense, and also a liability to governmental tax authorities. GENERAL JOURNAL Date Account Titles and Explanation Dec. 31 Income Taxes Expense Income Taxes Payable Debit Credit 4,020 4,020 Adjusting entry to record income taxes accrued in December. 4-44 International Case in Point Corporate income tax rates vary around the world. A recent survey shows that rates range from 9 percent in Montenegro to 55 percent in the United Arab Emirates. Worldwide, the average tax rate is 24 percent. The average rate in the United States is 40 percent, which is the highest rate among OECD countries.* In addition to corporate income taxes, some countries also (1) withhold taxes on dividends, interest, and royalties, (2) charge valueadded taxes at specified production and distribution points, and (3) impose border taxes such as customs and import duties. A few countries, including the Bahamas, have no corporate taxes. *KPMG Corporate Tax Rate Survey (2015). 4-45 Supporting the Matching Principle The matching principle underlies such accounting practices as: ◦ Depreciating plant assets. ◦ Measuring the cost of supplies used. ◦ Amortizing the cost of unexpired insurance policies. All end-of-the-period adjusting entries involving expense recognition are applications of the matching principle. 4-46 Matching Costs Costs are matched with revenue in one of two ways. 1. Direct association of costs with specific revenue transactions. The ideal method of matching revenue with expenses is to determine the actual amount of expense associated with specific revenue transactions. However, this approach works only for those costs and expenses that can be directly associated with specific revenue transactions. Commissions paid to salespeople are an example of costs that can be directly associated with the revenue of a specific accounting period. 4-47 Matching Costs (cont.) 2. Systematic allocation of costs over the useful life of the expenditure. Many expenditures contribute to the earning of revenue for a number of accounting periods but cannot be directly associated with specific revenue transactions. Examples include the costs of insurance policies and depreciable assets. In these cases, accountants attempt to match revenue and expenses by systematically allocating the cost to expense over its useful life. Straight-line depreciation is an example of a systematic technique used to match the cost of an asset with the related revenue that it helps to earn over its useful life. 4-48 Materiality Concept Materiality refers to the relative importance of an item or an event. An item is considered material if knowledge of the item might reasonably influence the decisions of users of financial statements. Accountants must be sure that all material items are properly reported in financial statements. 4-49 Materiality Concept (cont.) Immaterial items are those of little or no consequence to decision makers. ◦ The financial reporting process should be cost-effective—that is, the value of the information should exceed the cost of its preparation. ◦ Immaterial items may be handled in the easiest and most convenient manner. 4-50 Materiality and Adjusting Entries The concept of materiality enables accountants to shorten and simplify the process of making adjusting entries in several ways. For example: 1. Businesses purchase many assets that have a very low cost or that will be consumed quickly in business operations. Examples include wastebaskets, lightbulbs, and janitorial supplies. The materiality concept permits charging such purchases directly to expense accounts, rather than to asset accounts. This treatment conveniently eliminates the need to prepare adjusting entries to depreciate these items. 4-51 Materiality and Adjusting Entries (cont.) 2. 3. Some expenses, such as telephone bills and utility bills, may be charged to expenses as the bills are paid, rather than as the services are used. Technically this treatment violates the matching principle. However, accounting for utility bills on a cash basis is very convenient, as the monthly cost of utility service is not even known until the utility bill is received. Under this cash basis approach, the amount of utility expense recorded each month is actually based on the prior month’s bill. Adjusting entries to accrue unrecorded expenses or unrecorded revenue may actually be ignored if the dollar amounts are immaterial. 4-52 Materiality and Professional Judgment Whether a specific item or event is material is a matter of professional judgment. In making these judgments, accountants consider several factors: 1. The size of the organization. 2. The cumulative effect of numerous immaterial events. 3. Nature of the item. 4. Dollar amount of the item. 4-53 Your Turn: Materiality You as Overnight Auto’s Service Department Manager You just found out that Betty, one of the best mechanics that you supervise for Overnight Auto, has taken home small items from the company’s supplies, such as a screwdriver and a couple of cans of oil. When you talk to Betty, she suggests that these items are immaterial to Overnight Auto because they are not recorded in the inventory and they are expensed when they are purchased. How should you respond to Betty? 4-54 Effects of the Adjusting Entries Income Statement Adjustment Type I Converting Assets to Expenses Type II Converting Liabilities to Revenue Type III Accruing Unpaid Expenses Type IV Accruing Uncollected Revenue Revenue Expenses No effect Increase Increase Assets Liabilities Decrease Decrease No effect No effect Increase No effect Increase Increase Net Income Balance Sheet No effect Decrease Decrease No effect Increase No effect Increase Increase No effect Owners' Equity Decrease Increase Decrease Increase 4-55 Overnight’s Adjusted Trial Balance After these adjustments are posted to the ledger, Overnight’s ledger accounts will be up-to-date (except for the balance in the Retained Earnings account). 4-56 Ethics, Fraud, & Corporate Governance Improper accounting for operating costs has often resulted in the SEC bringing action against companies for fraudulent financial reporting. Expenditures that are expected only to benefit the year in which they are made should be expensed (deducted from revenue in the determination of net income for the current period). Companies that engage in fraud will often defer these expenditures by capitalizing them (they debit an asset account reported in the balance sheet instead of an expense account reported in the income statement). 4-57 Ethics, Fraud, & Corporate Governance (cont. 1) Prior to Enron and WorldCom, one of the largest financial scandals in U.S. history occurred at Waste Management. Waste Management was the world’s largest waste services company. The improper accounting at Waste Management lasted for approximately five years and resulted in an overstatement of earnings during this time period of $1.7 billion. Investors lost over $6 billion when Waste Management’s improper accounting was revealed. 4-58 Ethics, Fraud, & Corporate Governance (cont. 2) Waste Management’s scheme for overstating earnings was simple. The company deferred recognizing normal operating expenditures as expenses until future periods. These improper deferrals were accomplished in a number of different ways, many of which involved improper accounting for long-term assets. For example, Waste Management incurred costs in buying and developing land to be used as landfills (i.e., garbage dumps). 4-59 Ethics, Fraud, & Corporate Governance (cont. 3) Capitalizing these costs—treating them as long-term assets—was proper accounting. However, in certain cases, the company was not able to secure the necessary governmental permits and approvals to use the purchased land as intended. In these cases, the costs that had been capitalized and reported as landfills in the balance sheet should have been expensed immediately, thereby reducing net income for the year in which the company’s failure to obtain government permits and approvals occurred. 4-60 Learning Objective Summary LO4-1 LO4-1: Explain the purpose of adjusting entries. The purpose of adjusting entries is to allocate revenue and expenses among accounting periods in accordance with the realization and matching principles. These end-of-period entries are necessary because revenue may be earned and expenses may be incurred in periods other than the period in which related cash flows are recorded. 4-61 Learning Objective Summary LO4-2 LO4-2: Describe and prepare the four basic types of adjusting entries. The four basic types of adjusting entries are made to (1) convert assets to expenses, (2) convert liabilities to revenue, (3) accrue unpaid expenses, and (4) accrue uncollected revenue. Often a transaction affects the revenue or expenses of two or more accounting periods. The related cash inflow or outflow does not always coincide with the period in which these revenue or expense items are recorded. Thus, the need for adjusting entries results from timing differences between the receipt or disbursement of cash and the recording of revenue or expenses. 4-62 Learning Objective Summary LO4-3 LO4-3: Prepare adjusting entries to convert assets to expenses. When an expenditure is made that will benefit more than one accounting period, an asset account is debited and cash is credited. The asset account is used to defer (or postpone) expense recognition until a later date. At the end of each period benefiting from this expenditure, an adjusting entry is made to transfer an appropriate amount from the asset account to an expense account. This adjustment reflects the fact that part of the asset’s cost has been matched against revenue in the measurement of income for the current period. 4-63 Learning Objective Summary LO4-4 LO4-4: Prepare adjusting entries to convert liabilities to revenue. Customers sometimes pay in advance for services to be rendered in later accounting periods. For accounting purposes, the cash received does not represent revenue until it has been earned. Thus, the recognition of revenue must be deferred until it is earned. Advance collections from customers are recorded by debiting Cash and by crediting a liability account for unearned revenue. This liability is sometimes called Customer Deposits, Advance Sales, or Deferred Revenue. As unearned revenue becomes earned, an adjusting entry is made at the end of each period to transfer an appropriate amount from the liability account to a revenue account. This adjustment reflects the fact that all or part of the company’s obligation to its customers has been fulfilled and that revenue has been realized. 4-64 Learning Objective Summary LO4-5 LO4-5: Prepare adjusting entries to accrue unpaid expenses. Some expenses accumulate (or accrue) in the current period but are not paid until a future period. These accrued expenses are recorded as part of the adjusting process at the end of each period by debiting the appropriate expense (e.g., Salary Expense, Interest Expense, or Income Taxes Expense), and by crediting a liability account (e.g., Salaries Payable, Interest Payable, or Income Taxes Payable). In future periods, as cash is disbursed in settlement of these liabilities, the appropriate liability account is debited and Cash is credited. 4-65 Learning Objective Summary LO4-6 LO4-6: Prepare adjusting entries to accrue uncollected revenue. Some revenues are earned (or accrued) in the current period but are not collected until a future period. These revenues are normally recorded as part of the adjusting process at the end of each period by debiting an asset account called Accounts Receivable, and by crediting the appropriate revenue account. In future periods, as cash is collected in settlement of outstanding receivables, Cash is debited and Accounts Receivable is credited. 4-66 Learning Objective Summary LO4-7 LO4-7: Explain how the principles of realization and matching relate to adjusting entries. Adjusting entries are the tools by which accountants apply the realization and matching principles. Through these entries, revenues are recognized as they are earned, and expenses are recognized as resources are used or consumed in producing the related revenue. 4-67 Learning Objective Summary LO4-8 LO4-8: Explain the concept of materiality. The concept of materiality allows accountants to use estimated amounts and to ignore certain accounting principles if these actions will not have a material effect on the financial statements. A material effect is one that might reasonably be expected to influence the decisions made by the users of financial statements. Thus, accountants may account for immaterial items and events in the easiest and most convenient manner. 4-68 Learning Objective Summary LO4-9 LO4-9: Prepare an adjusted trial balance and describe its purpose. The adjusted trial balance reports all of the balances in the general ledger after the end-of-period adjusting entries have been made and posted. Generally, all of a company’s balance sheet accounts are listed, followed by the statement of retained earnings accounts and, finally, the income statement accounts. The amounts shown in the adjusted trial balance are carried forward directly to the financial statements. 4-69 End of Chapter 4 4-70