International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD)

Volume 4 Issue 2, February 2020 Available Online: www.ijtsrd.com e-ISSN: 2456 – 6470

Organizational Justice and Academic Staff Performance

among Public and Private Tertiary Institutions in

South-South States of Nigeria

Musah Ishaq, Prof. Lilian O. Orogbu, Dr. Ndubuisi-Okolo Purity U.

Department of Business Administration, Faculty of Management Sciences,

Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, Nigeria

How to cite this paper: Musah Ishaq |

Prof. Lilian O. Orogbu | Dr. NdubuisiOkolo Purity U. "Organizational Justice

and Academic Staff Performance among

Public and Private Tertiary Institutions in

South-South States of Nigeria" Published

in

International

Journal of Trend in

Scientific Research

and Development

(ijtsrd), ISSN: 24566470, Volume-4 |

Issue-2, February

IJTSRD30205

2020, pp.1042-1055,

URL:

www.ijtsrd.com/papers/ijtsrd30205.pdf

ABSTRACT

The organizational conflicts among employers and employees in tertiary

institutions most especially public institutions has remained a recurring spike

in Nigeria that undermine the overall performance of lecturers and students

outcomes in the institutions. The specific objective of this research is to

investigate the extent of significant differences in organizational justice among

lecturers in public and private universities in relation to academic staff

commitment in tertiary institutions in South-South States in Nigeria which is

also in line with the research question and hypothesis. The research adopted a

descriptive survey research design, the population of the study is 400.

Factorial analysis of variance was used to test hypothesis with the aid of

Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 20. Cronbach alpha was

used to test the reliability of the instrument. The findings revealed that there

is level of significant differences in interactional justice in relations to lecturer

students relationship between academic staff in public and private

universities in South-South Nigeria, in conclusion equitable distribution of

resources, fair procedures for job decisions, with appropriate allocation of

resources and fair communication of decisions will result in high academic

staff performance towards higher academic excellence. The researcher

recommends among others that management of both public and private

universities should come out with supportive policies as a way of promoting

interactional justice toward maintaining lecturer-student relationship which

can be done through integrating the philosophy of target education

programme established in 1990 by Aumua and Drake (2002).

Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and

International Journal of Trend in Scientific

Research and Development Journal. This

is an Open Access

article

distributed

under the terms of

the Creative Commons Attribution

License

(CC

BY

4.0)

(http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by

/4.0)

KEYWORDS: Organizational Justice, Interactional Justice, Academic Staff

Performance and Public and Private Tertiary Institutions

1. INRODUCTION

Teaching is a very demanding professions such that the

success of the educational institutions depends on highly

committed and dedicated Lecturers. In Nigeria, the teaching

profession is encumbered with a lot of injustices that have

the capacity of lowering the level of commitment of lecturers

towards attainting quality academic delivery. These

injustices occur in terms of distributive justice, procedural

justice, informational justice and interactional justice which

determine the extent to which academic staff perceive

organizational justice in relation to their performance in the

institutions.

However, academic staff are not satisfied with the ways

rewards are being apportioned which is not proportional to

inputs based on the principle of equity. The evaluation of

academic staff performance and reward in terms of wages,

promotions, work roles and workloads are not fairly

distributed, which invariably affects their level of affective

commitment to performance. The universities managements

do not properly apply the principles of distributive justice to

allocation of rules based on equality, equity and needs of

academic staff.

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

Moreover, the procedure used to allocate rewards and

benefits to academic staff is not fair, which affects their

emotional and psychological impact on the courses they

handle. The decision criteria and control process at the

workplace are not fair, which makes it look biased,

inaccurate, lack relationship, lack representation of all

concerned and inconsistent with ethical norms and

indirectly affect the extent of input of academic staff in their

respective subject areas. It is clear that in private institutions

in Nigeria, the decision to allocate rewards and take

decisions rests solely on the owners of private institutions

without prior consultation of academic staff. Thus, the

question remains whether such experience is found in public

universities, and if found, to what degree compare with

experiences of lecturers in public universities in SouthSouth, Nigeria. Though, lack of adoption of appropriate and

generally acceptable procedures for rewards has affected the

level of cognitive, affective, behavioural reaction,

psychological wellbeing with feeling of reputation of life

satisfaction and subject knowledge among academic staff in

tertiary institutions in South-South, Nigeria.

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1042

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

The evaluation of employee performance in the Nigerian

tertiary institutions especially academic staff can be assessed

in terms of the degree of commitment to academic

performance, lecturers’ degree of subject knowledge of the

courses taken, level of communication skill and lecturerstudent relationship among academic staff in the tertiary

institutions in South-South, Nigeria. These variables

determine the level of academic staff performance in relation

to organizational justice in both the private and public

tertiary institutions in Nigeria; commitment is the relative

strength of lecture’s identification with and involvement in a

particular institution. Academic staff level of commitment

has three components, namely: a lecturer’s belief in and

acceptance of institution’s goals and values; his/her

willingness to work towards accomplishing the institution’s

goals; his/her strong desire to continue as institution’s

member.

Also, lecturer’s subject knowledge (competence) remains

one of the major determinants of students’ academic

achievements. Teaching is a collaborative process which

encompasses interaction by both learners and the lecturer.

Lecturer subject knowledge in teaching process is a

multidimensional concept that measures numerous

interrelated aspects of sharing knowledge with learners

which include communication skills, subject matter

expertise, lecturer attendance, teaching skills and lecturer

attitude which revolve around the extent academic staff

perceive organizational justice in the institutions. As

lecturers spend an incredible amount of time with their

students over the course of the year, it is the responsibility of

lecturers to foster an inclination for learning and this can be

done when they perceive procedural justice in relation to

their input as obtainable in other tertiary institutions in

Nigeria. Studies have revealed that the relationship between

lecturers and students is an important predictor of academic

engagement and achievement. In fact, the most powerful

weapon lecturers have when trying to foster a favorable

learning climate is positive relationships with their students.

Students who perceive their teachers as more supportive

have better achievement outcomes (Boynton & Boynton,

2005). Additionally, the learning environment plays a

significant role in maintaining student interest and

engagement. When students feel a sense of control and

security in the classroom, they are more engaged because

they approach learning with enthusiasm. Students become

active participants in their own education (Skinner & Green,

2008). Therefore, the first step to helping a student become

more motivated and engaged, and thus academically

successful, is building and maintaining positive lecturerstudent relationships which can justify a perception of

procedural justice(Maulana, Opdenakker, Stroet, & Bosker,

2013). The general objective of the study is to determine the

extent of significant difference in organisational justice in

relation to academic staff performance between public and

private universities in South-South Nigeria.

In the light of above scenario, and in order to fill the gap the

study intends to compare the extent of Significant difference

in organizational justice among lecturers in public and

private universities in relation to academic staff

performance in tertiary institutions in South-South states

Nigeria.

Objective of the Study

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

The general objective of the study is to determine the extent

of significant difference in organisational justice in relation

to academic staff performance between public and private

universities in South-South Nigeria. The specific objective is:

A. To investigate if there is variation in interactional justice

in relation to lecturer’s-students’ relationship between

academic staff in public and private universities in

South-South Nigeria.

2. Review of Related Literature

2.1. Interactional Justice

The third demission of organizational justice is interactional

justice. (Bies & Moag, 2008).Interactional justice exist when

decision makers treat people with respect and sensitivity

and explain the rationale for decisions thoroughly.

Therefore, interactional justice is the treatment that an

individual or employee receives as decision made (Colquitt,

2001).

It concerns the fairness of the interpersonal treatment

individuals are given during the implementation of

procedures. Cropanzano, Prehar and Chen (2007) simply

refer to interactional justice as “usually operationalized as

one-to-one transactions between individuals”. According to

Bies (2008), interactional justice focuses on employees'

perceptions of the interpersonal behaviour exercised during

the representation of decisions and procedures.

Interactional justice is related to the quality of relationships

between individuals within organizations (Folger &

Cropanzano, 2008). Although some scholars view

interactional justice as a single construct, others have

proposed two dimensions of interactional justice (Bies,

2008; Lind & Tyler, 2008). The two dimensions of

interactional justice proposed are interpersonal and

informational justice. These two dimensions of interactional

justice are related to each other. However, research

recommends that both concepts should be looked at

differently since they have differential consequence on

justice perceptions (Colquitt, 2001 ;).

In some respects, interactional justice falls under the

umbrella term of procedural justice, but is significant enough

to be considered in its own right. It refers to the quality of

the interpersonal treatment received by those working in

organization, particularly as part of formal decision making

procedures. Bies and moag (2008) identify some key aspects

of interactional justice, which can enhance people’s

perceptions of fair treatment,as follows:

Truthfulness: Information that is given must be

realistic and accurate, and presented in an open and

forthright manner.

Respect: Employees should be treated with dignity,

with no recourse to insults or discourteous behaviour.

Propriety: Questions and statements should never be

‘improper’ or involve prejudicial elements such as

racism or sexism.

Justification: When a perceived injustice has occurred,

giving a ‘social account’ such as an explanation or

apology can reduce or eliminate the sense of anger

generated.

Authority: Perceptions about a manager’s authority can

affect procedural justice judgement. Three aspects of

authority having a bearing on this judgement are trust,

neutrality and standing (Lind and Tyler, 2008).

Managers will be considered trustworthy if their

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1043

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

intentions are clear and fair and their behaviour

congruent with these intentions. Neutrality refers to the

use of facts to make an unbiased decision, while

standing implies a recognition accorded to managers

who treat others with dignity, politeness and respect for

their rights.

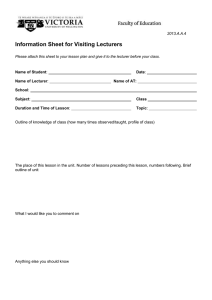

Figure 1: Organizational Justice Relationship with

Academic Staff Performance

Source: Cropanzano, R., Bowen, D. E. & Gilliland, S. W.

(2007). The Management of Organisational Justice.

Academy of Management Perspectives, 21, 34-48.

2.1.1. Academic Staff (Employee) Performance

Performance has been the most vital issue for every

organization, either profit or non-profit organisation. It is

expedient for mangers to know the factors that affect the

performance. However, it is quite difficult in actual sense to

measure performance, but in this context, performance is

taken to be the productivity that is, the relationship between

input and output (Ebhote, 2015).

Performance is defined as a degree of viability of achieving

predetermined Organizational objective (Chan & Baum,

2007). For instance, employee performance says a college

professor is evaluated on three functions: teaching, research

and community service. Therefore, the job outcome of a

Professor is a measure of his/her performance in a job.

Generally speaking, employees performance on the job is

equal to the sum of performance recorded on the major job

functions or activities (Bernardin, 2010). According to Chan

and Quarles (2012), performance encompasses both

quantitative and qualitative measurement of efforts and is

used to achieve the aim of an organization. Performance

encompasses processes such as; goal setting, measurement,

assessment, feedback, rewarding for excellent results, use of

corrective measures in situation of bad result (Kaplan, 2001;

Chang, 2006). Lawrie and Gobbold (2004) stated that

performance is an important guidance in respect to the

expectations of the employees and goals of the organization

in general. According to the authors, this guidance is used by

both public and private sector organizations to maintain

their competitiveness with respect to other firms. Aim of

performance measurement is focused on: increasing

employees job satisfaction, motivation, providing on time

and quick feedback, providing fairness in the structure of the

organization, providing equal employee opportunities, and

helping them improve themselves (Griffith, 2003).

Employee is a person who is hired for a wage, salary, fee or

payment to perform work for an employer (Balyan, 2012).

Both private and public sector organizations are established

to achieve corporate goals using resources such as men,

machines, materials and money. All these resources are

important, but most important among them are the

employees.

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

Nowadays, majority of firms are competing favorably with

one another in business environment to maintain large

market shares and firms who valued their employees always

take the lead in its market. The role of employees on the job

is vital for the growth of any organization. The performance

of employees on different jobs through mutual effort is

needed for the success of any unit/department. The nature

of relationships that employees have with their supervisors

or co-workers in the organization affects their commitment

towards work and organizational performance either

positively or negatively. Employees commitment towards

work and organizational performance affects negatively

management policy in deciding work assignments and

opportunities in the workplace without fairness among

employees (Griffeth & Gaertner, 2000; Ellen et al. 2001).

When some employees perceive that their boss uses

favoritism to please one party against the other in the

workplace, their morale towards work will be relatively low.

The top manager is the most important as the enabler of the

employee commitment to jobs and to the organization

(Corporate Leadership Council, 2004).

In spite of this, Levin and Rosse (2001) wrote that

developing an effective working relationship with employees

is considered one of the most effective ways that managers

can retain employees in the organization, and use of nonmonetary recognition in form of acknowledgment from coworkers and managers is very important.

According to Daniel (2010), employee performance can be

defined in terms of whether employees’ behaviors

contribute to organizational goals. Performance can be seen

as an individual, group, or organizational task performance.

However, an employees job consists of a number of

interrelated tasks, duties, and responsibilities which a job

holder needs to carry out, whereas performance is a

behavior or action that is relevant for the organization’s

goals and that can be measured in terms of the level of

proficiency or contribution to goals that is represented by a

particular or set of actions (Campbell, 2007). Employee

performance is normally looked at in terms of outcomes.

2.1.2. Lecturer-student Relationship

Many researchers assume lecturer–student relationships to

be determinants of students’ academic outcomes and, so,

measure the effects of these relationships on different

academic parameters. For instance, Hamre and Pianta

(2001) found evidences of lecturer–student relationship

conflict evaluated in the first grade on achievement seven

years later, controlling for relevant baseline child

characteristics. Connell and Wellborn (1991), Deci and Ryan

(2000), in their investigation found that the role of relations

with lecturers in students’ academic attainment variables

emanates extensively from the Self-Determination Theory

(SDT). This theory is used as a theoretical framework that

links teacher–student interactions with students’

engagement and, consequently, their achievement. Of special

importance for the purpose of this study is a mini-theory

within SDT called Basic Needs Theory (Rani, Garg, & Rastogi

2012) that assumes three basic psychological needs:

competence, autonomy and relatedness. The social context

can either support or thwart these needs, thereby positively

or negatively affecting students’ engagement. Based on this

theory, teachers’ participation is important for satisfying the

need for relatedness between organizational justice and

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1044

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

academic staff performance. This mean to the degree of

quality interpersonal relations with students and is

manifested through teachers having time for students, being

flexible to their needs and expressing positive feelings

toward them through perception of organizational justice.

Many researchers found that lecturers’ interpersonal

relationship with management and students seems to be the

strongest predictor of lecturers’ academic achievement

among all of the other presumably important dimensions of

lecturer’ behavior, attitude and action in perception of

organizational justice; the students of highly involved

lecturer perceive their teachers not only as involved but also

as giving more structure and support to students’ autonomy,

independently of the lecturer actual behavior in these two

dimensions (Furrer and Skinner 2003; Skinner and Belmont

1993). Meanwhile, the meta-analysis from Stroet,

Opdenakker and Minnaert (2013) actually support that

interactional justice positively relate to lecturer-student

relationship since students also assess organizational justice

through their lecturer’s interaction on daily academic

activities. Based on a systematic review of the evidence on

the effects of need supportive teaching on early adolescents’

academic motivation and engagement, the researchers

affirmed that, although results revealed positive relations of

each of the three dimensions of need supportive teaching

with students’ motivation and engagement, there search on

their unique importance is scarce and needs further

investigation.

Moreover, the relationship between students’ need for

relatedness and their academic outcomes is clearly

documented. The sense of relatedness tapped by the

measures of school climate and the quality of teacher–

student relations, as well as the feelings of belonging,

acceptance, importance, and interpersonal support, are

related to important academic outcomes, including positive

effect (Skinner and Belmont, 1993), effort and self-efficacy

(Sakiz et al., 2012), engagement (Furrer and Skinner, 2003;

Skinner and Belmont, 1993;Wu et al,. 2010),self-reported

academic initiative (Danielsen et al., 2010), interest in school

(Wentzel, 1998), self-regulated learning (Rani,Garg &

Rastogi2012), and grades (Furrer and Skinner, 2003;

Niehaus et al. 2012; Wuetal,.2010).Studies on effect of

academic achievement on lecturer–student relationship that

investigated the relation between lecturer–student

relationships and academic achievement usually test for the

reciprocal effect of achievement on lecturer–student

relationships. They found that a positive significant

relationship exists between teacher-student relationship

with interactional justice in the institution due to closeness

and exchange of ideas and knowledge the students derive

from their lecturers. However, some studies investigated the

role of students’ characteristics (including academic

achievement) in the formation of lecturers’ preference for

students. Lecturers prefer an institution where aspects of

organizational justice are implemented to the letter which

influence their intimate relationship with the students.

Lecturer acceptance or preference is defined as the extent to

which a lecturer likes a specific student (Mercer and

DeRosier, 2010) and is usually expressed in lecturers’

differential interactions with students, although lecturers

may not be aware of this unequal treatment. This reasoning

assumes a directionality of influence that is opposite to the

one mentioned as students’ achievement is considered as

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

predictor and lecturers’ perception is considered as

outcome.

This dependent variable (lecturer-student relationship) has

received some empirical support such as students’ academic

achievement which was found to contribute to lecturers’

perceptions of their students (Aluja-Fabregat, BallesteAlmacellas and Torrubia-Beltri, 1999) and lecturers prefer

students with higher achievements ( Davis, 2006; Kuklinski

and Weinstein, 2001).

The question of directionality of influence of lecturerstudent relationship in terms of lecturers’ expectations and

students’ achievement was addressed in the study of Crano

and Mellon (1978).

The findings suggest that lecturers’ expectations cause

students’ academic achievement positively where they

perceive higher level of full implementation of

organizational justice. This invariably is the mediating role of

student perceptions and assessment of lecturers by students.

The relation between lecturers’ acceptance expressed in

teachers’ differential behavior which is characterized by

interactional justice toward students and their academic

outcomes can operate directly without involving students’

interpretative processes. However, the contributions of

teachers’ perceptions to changes in students’ academic

outcomes are probably mediated through students’

perceptions of their lecturers’ support (Kuklinski and

Weinstein 2001; Skinner et al. 2008). This mediation

depends on two conditions: (1) the differences in lecturer

acceptance of students are expressed in the degree of

lecturers’ supportive behavior and (2) students have the

capacity to perceive the expressed level of teacher support.

With regard to the first condition, Babad (1993) reported a

discrepancy in students’ and lecturers’ perception of

lecturers’ emotional support for students regarding their

achievement: students perceived that the high achievers

receive more emotional support from their lecturers which

is an indication of fairly interactional justice perceived by

lecturers whereas lecturers reported being more supportive

toward low achievers. Although both perspectives can be

regarded as valid, this result could also imply the possibility

that lecturers are unaware of their differential behavior.

Also, Kuklinski and Weinstein (2001) reported that lecturers

differ in their propensities to treat high and low achievers

differently: in some classrooms, lecturers’ differential

behavior is more salient than in others. The second

condition, i.e. students’ capacity to perceive lecturers’

differential treatment, depends on students’ developmental

level. In SDT, the measures of self are predicted to be

mediators between lecturers behavior and students’

academic behavior and outcomes, thus assuming that it is

not lecturers’ behaviour per say that influences students’

motivation, but rather, how they perceive this behavior.

Results of a recent meta-analysis by Stroet et al. (2013)

indicated that students’ perceptions of need supportive

teaching are generally positively related to their motivation

and engagement. However, in the small body of studies that

used observations or lecturer perceptions as a measure of

need supportive teaching, much smaller associations or even

no associations were found. This finding reveals that student

perceptions of their relationship with their lecturer have a

larger impact on motivation and engagement than the actual

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1045

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

lecturers’ behavior. Lecturer–student relationship and its

relation to academic achievement in different grade levels.

The nature of the lecturer–student relationship and its

meaning for students change over the school years. In

transition to adolescence, there is a shift in students’

orientation from relations with lecturers to increased peer

orientation. Studies mostly report a decrease in the quality

of lecturer–student relationships (Chang et al. 2004; Moritz

Rudasill et al. 2010; O’Connor 2010) which may be

attributed in part to changes in school context (more

students in the class, higher school demands, and fewer

opportunities for individual contact with lecturers) and

partly to an increase in students’ need for autonomy (Chang

et al. 2004). But despite this decrease, students’ relations

with lecturers remain positively related to students’

academic outcomes (Danielsen et al. 2010; Davidson et al.

2010; Niehaus et al. 2012).

Another aspect of age dependency in lecturer–student

relationships is the development of students’ capacity to

perceive the differential lecturer behavior toward different

students.

Developmental changes in students’ social cognition also

imply an increased capacity to perceive the differential

lecturers treatment (Wentzel. 1998), thus assuming a

moderating effect of students’ age on the links between

lecturer acceptance, student-perceived lecturer support, and

achievement. However, research has mostly been focused on

students at a single age, ignoring the age-related differences

in the magnitude of the relation between lecturer

perceptions and achievement.

In tertiary institutions as it relates to organizational justice

and academic staff performance as baseline of interest, the

majority of studies mentioned implied that the lecturer–

student relationship was assumed to be a predictor and

academic variables were seen as an outcome, that academic

performance of students is influenced by relations with

lecturers. In this study, three alternative explanations of the

relation between lecturer–student relationships are

explained in three forms (1) lecturer acceptance of students

influences students’ academic outcomes which is determined

by the students’ perceived personal support from their

teachers. Mercer and DeRosier (2010) reported lecturer

acceptance to be a predictor of students’ perceptions of

lecturer-student relationship quality. Students’ ability to

recognize the quality of lecturers’ treatment is predicted to

be crucial for the differences in students’ academic

achievement. (2) Lecturer acceptance of students mostly

reflects actual student performance, which implies the

opposite causal direction, namely, the influence of students’

academic performance on lecturers’ acceptance. Research

shows that students with higher academic motivation,

achievement, and self-regulation and stronger identity as

student form better relations with their lecturers (Babad

1993; Davis 2006; Wentzel and Asher 1995). Thus, it is

possible that lecturers just prefer students who are easier to

work with and more rewarding for their effort. (3) The third

possible explanation is the reciprocal model which assumes

that, independently of the initial direction of causality, the

relation between lecturer acceptance and students’ academic

outcomes becomes reciprocal, i.e. lecturers form more

positive relations with students that achieve better, which

influences students’ perceived support from their teacher,

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

and this positive relation reinforces students’ academic

performance. This is the relation that Skinner et al. (2008)

described as “dynamics”: the internal and external causal

feedback loops that serve to promote or undermine the

quality of children’s performance in school over time.

Students who are engaged and perform better receive more

lecturer involvement than disaffected students, where

lecturers increasingly withdraw their support and/or

become more controlling in time. In that way, the initial

dynamics are amplified (Hughes et al. 2008; Skinner and

Belmont 1993). With regard to developmental changes in the

lecturer–student relationship (e.g., Chang et al,2004;

MoritzRudasilletal.2010), it is clear that organizational

justice in terms of interactional justice influences the degree

of lecturer-student relationship in the institution which

directly increases students’ commitment and academic

performance.

2.1.3.

Relationship between Interactional Justice and

Lecturer-student Relationship

Interactional justice involves considering interpersonal

communication that links with procedures as fair.

Interactional justice is a concept that concerns perceptions

of employees about the treatment they have received during

the application of organizational policies. According to

Folger and Bies (1989), indicators of the existence of

interactive justice are demonstrating due respect to

employees, introducing consistent criteria, giving feedback

on time and behaving appropriately and sincerely. Findings

from the study conducted by Wasti (2001), the perception of

positive interactive justice increases the positive teacherstudent relationship that lecturers feel towards their

institutions. With regards to interactive justice, Ajala (2000)

asserted that the way a person perceives his surroundings

influences that a person actually behaves and relates with

people in that environment. In fact, a sense of interactive

justice in the school workplace is dependent upon

administrative behaviours such as equity, sensitivity to the

plight of lecturers, respect, honesty and ethical interactions

(Hoy & Miskel, 2005). Fox (2008), in his study, found that a

positive interactive justice makes the school a good place to

be, a satisfying and meaningful situation in which lecturers

spend a substantial portion of their time relating and

discussing academic issues with their students. This implies

that lecturers from universities with better environment

characterized with interactional justice, do better in research

work, enjoy welfare scheme, have access to better teaching

facilities, perform better and feel fulfilled than those with

perceived negative interactive justice. Student perception

plays an important role in incentive. In fact, research

suggests that the most powerful predictor of a student

motivation is the student’s perception of control. Perceived

control is the belief that one can determine one’s behavior,

influence one’s environment, and bring about desired

outcomes. Because students already have a history of

experiences with whether lecturers are attuned to their

needs, lecturers build on these experiences (Skinner &

Greene, 2008). Therefore, a student’s perception of the

teacher’s behavior impacts the relationship. Students who

feel their teacher is not supportive and interactive towards

them as a result of unfair treatment by management have

less interest in learning and are less engaged in the

classroom (Rimm-Kaufman and Sandilos, 2012). Students

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1046

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

read and perceive facial expression of their lecturer as they

meet and interact daily in the classroom.

Employees seek justice when communicating with their

managers and other relevant authorities in the organization.

Interactional justice, based on peer to peer relationships, is

the perception of justice among employees that is concerned

with informing employees of the subjects of organizational

decisions, as well as about attitudes and behaviors to which

employees are exposed during the application of

organizational decisions (Cohen-Charash and Spector, 2009;

Liao and Tai, 2008). In other words, it expresses the quality

of attitude and behaviors to which employees are exposed

during the practice of (distributive and procedural)

operations by managers (Greenberg, 2008; Liao and Tai,

2008). It is stated that interactional justice is composed of

two sub-dimensions: interpersonal justice and informational

justice (Cropanzano, 2007). Interpersonal justice points at

the importance of kindness, respect and esteem in

interpersonal relations, particularly in the relationships

between employees and managers. Informational justice, on

the other hand, is about informing employees properly and

correctly in matters of organizational decision making.

According to Cojuharenco and Patient (2013), employees

focus on job results when they consider justice in the

workplace, and they are likely to focus on the methods of

communication and reciprocal relationships within the

organization when they consider injustice. If the interactions

of managers or manager representatives with employees

occur in a just way, employees will respond with higher job

performance (Settoon, 2008; Masterson, 2010; Cropanzano,

2007). Interactional justice can lead to strong interpersonal

interactions and communication over time (Lerner, 2008;

Cropanzano, 2007). According to social exchange theory, the

positive or negative effect of employee-administration

relationships on job performance stems from interactional

justice (Cohen-Charash and Spector, 2009; Settoon, 2008;

Wayne, 2010; Cropanzano 2007). According to this theory, if

employees are satisfied with their relationships with the

administration, apart from their formalized roles, they will

volunteer to acquire additional roles, which will increase

their contextual performance.

Interactional justice is a concept that emphasizes the quality

of the relationships among employees in an organization.

Interactional justice involves such behaviors as valuing

employees, being respectful, and announcing a decision

considered as a social value to employees (İçerli, 2010).

Interactional justice claims that individuals are not only

interested in the fairness of the process in assessing justice,

but they are also interested in the behavior of the people

authorized to manage this process (Çakmak, 2005). From

this perspective, interactive justice is defined as the

perceived justice of interpersonal behaviors during the

application of processes (Cohen-Charash & Spector, 2009).

The classification of organizational justice by Donovan et al.

(1998) approached it in two dimensions which are:

Interpersonal justice and Informational justice. The

relationship of employees to managers is inter-employee

relationships. This may also be considered within

interactional justice as the items included in this scale

overlap with the characteristics of interactional justice.

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Leader-Member Exchange (LMX)

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

This study is anchored on leader-member exchange theory

which describes organizational settings, aspects of the

exchange relationship between a supervisor and a

subordinate are considered to be fundamental to

understanding employee attitudes and behavior ( Napier &

Ferris, 1993). Traditional leadership theories seek to explain

leadership as a function of the personal characteristics of the

leader, the features of the situation, or an interaction

between the leader and the group (Gerstner & Day, 1997).

These theories have failed to recognize that the relationship

between a leader and a subordinate may have an impact

upon the attitudes and behavior of the subordinate.

Dansereau, Graen, and Haga (1975) proposed that leadermember relationships are heterogeneous, that is, that the

relationship between a leader and a member contained

within a work unit are different, and that each leadermember relationship is a unique interpersonal relationship

within an organizational structure. They coined the term

vertical dyad linkage (VDL) to describe the dyadic

relationship between a leader and a subordinate. VDL theory

focuses on reciprocal influence processes within dyads.

Graen(1976) also argued that research should focus on the

behavior of the leader and the subordinate within the

supervisor-subordinate dyad, rather than the supervisor and

his other workgroup. Graen (1976) developed the

theoretical base of the leader-member exchange model of

leadership by building on role theory.

The theoretical basis of leader-member exchange theory is

the concept of a developed or negotiated role. Dansereau,

Graen, and Haga (1975), and Graen and Ferris (1993)

initially conceptualized and tested the negotiating latitude

construct in an investigation designed to study the

assimilation of administrators into an organization.

Negotiating latitude was defined as the extent to which a

leader allows a member to identify his or her role

development. This negotiating latitude was hypothesized as

being central to the evolution of the quality of the leadermember exchange (Dansereau, Graen, and Haga, 1975).

Leader-member exchange theory is a subset of social

exchange theory, and describes how leaders develop

different exchange relationships over time with various

subordinates of the same group (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga,

1975; Graen & Ferris, 1993). Thus, leader-member exchange

refers to the exchanges between a subordinate and his or her

leader. The leader-member exchange model provides an

alternative approach to understanding the supervisorsubordinate relationship. The leader-member exchange

model is based on the concept that role development will

naturally result in differentiated role definitions and in

varied leader-member exchanges. During initial interactions,

supervisors and their subordinates engage in a role-making

process, whereby the supervisor delegates the resources and

responsibilities necessary to complete a task or duty.

Subordinates who perform well on their task or duty will be

perceived as more reliable by supervisors and, in turn, will

be asked to perform more demanding roles (Dienesch &

Linden, 1986). Leaders usually establish a special exchange

relationship with a small number of trusted subordinates

who function as assistants, lieutenants, or advisors. The

exchange relationship established with remaining

subordinates is substantially different (Yukl, 1994).

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1047

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

Much of the research on leader-member exchange divides

the subordinate's roles and the quality of the leader-member

exchange into two basic categories based on the leaders' and

members' perceptions of the negotiating latitude: the ingroup and the out-group (Dansereau, Graen & Haga, 1975;

Graen, Napier & Ferris, 1993; Linden & Graen, 1980;

Scandura & Graen, 1984; Vecchio, 1982). In-group or highquality leader-member exchange is associated with high

trust, interaction, support, and formal/informal rewards. Ingroup members are given more information by the

supervisor and report greater job latitude. These in-group

members make contributions that go beyond their formal

job duties and take on responsibility for the completion of

tasks that are most critical to the success of the unit (Linden

& Graen,1980). Conversely, out-group or low-quality leadermember exchange is characterized by low trust, interaction,

support, and rewards. Out-group relationships involve those

exchanges limited to the employment contract. In other

words, out-group members perform the more routine,

mundane tasks of the unit and experience a more formal

exchange with the supervisor (Linden & Graen, 1980). Graen

and Ferris (1993) and Linden and Graen (1980) provide

evidence that in-group and out-group memberships tend to

develop fairly quickly and remain stable.

Similarly, social exchange theory (Emerson, 1962)

recognizes how dyadic relations develop within a social

context. Social exchange theory describes how power and

influence among leaders and members are conditioned on

the availability of alternative exchange partners from whom

these leaders and members can obtain valued resources.

Blau (1964) also distinguished the differences between

social and economic exchange, noting that social exchange

tends to produce feelings of personal obligation, gratitude,

and trust, whereas economic exchange does not. This

distinction between social and economic exchange is

fundamental to the way in which out-group or low quality

exchanges and in-group or high quality exchanges have been

distinguished in leader-member exchange research (Linden

& Graen, 1980; Linden, Wayne, & Stilwell, 1993). Low quality

leader member relations have been characterized in terms of

economic exchanges that do not progress beyond the

employment contract, whereas high quality leader-member

relations have been characterized by social exchanges that

extend beyond the employment contract.

This relevance of the theory to the work is based on the

premise that it meditates the relationship of distributive

justice-employee performance in organization. Leadermember exchange theory and its relationship are embedded

in social exchange and, in return, it is an obligation for

subordinates that they have to reciprocate the high quality

relationship with their managers\leaders.

2.3. Empirical Review

Ogwuche and Apeiker (2016) conducted a study on influence

of interactional justice and organizational support on

organizational commitment among academic staff of Benue

State University, Makurdi, Nigeria. The aim of the study was

to examine the influence of interactional justice on

organizational support and commitment among academic

staff. The study adopted a cross sectional design. A total of

221 respondents were selected. Data were gathered through

a structured questionnaire and analyzed using regression

model. Findings revealed that organizational support has a

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

significant joint influence on organizational commitment

among lecturers. A significant joint influence exists between

organizational support and interactional justice among

lecturers and interactional justice positively influence

organizational commitment. The study concluded that

organizational support and interactional justice have

significant joint influence on organizational commitment.

This implies that organizational support and interactional

justice are co-determinants of organizational commitment

among lecturers. It therefore, means that high level of

university support with a corresponding appreciable level of

interactional justice can give rise to high organizational

commitment among lecturers, whereas, low level of

organizational support coupled with insignificant level of

interactional justice may lead to decline in level of

commitment among lecturers. The study recommended that

management of Nigerian universities should come out with

supportive policies as a way of motivating lecturers to be

committed to their academic work.

A study on organizational justice and job performance of

lecturers in federal universities in South South Zone of

Nigeria was conducted by Efanga, Aniedi and Identa (2015).

The objective of the study was to determine the relationship

between organizational justice and lecturers’ participation in

co-curricular activities, involvement in community service

and lecturers’ teaching behavior in the selected universities

in South South, Nigeria. The study adopted a descriptive

survey design. A sample size of 529 lecturers was selected

from a total population of 5664 lecturers as at 2013/2014

session. Data were gathered from questionnaire

administered and thus analyzed using simple regression

model. The results revealed that there is a significant and

positive relationship between organizational justice and

lecturers’ participation in co-curricular activities in the

selected universities in the South South zone of Nigeria. Also,

a significant relationship exist between organizational

justice and lecturers’ involvement in community service in

the selected universities in the South South zone of Nigeria.

Finally, lecturers’ teaching behaviour is significant and

positively related with organizational justice among

lecturers in the selected universities in the South South zone

of Nigeria. The study concluded that lecturers’ participation

in co-curricular activities, lecturers’ involvement in

community service and lecturers’ teaching behavior are

determinants of lecturers’ job performance which is

influenced by the degree of implementation of organizational

justice in the institutions. The study recommended that

university management should implement equitable reward

system in the universities in order to improve lecturers’

morale and productivity.

Usikalu, Ogunleye and Effiong (2015) conducted a study on

organizational justice, job satisfaction and employee

performance among Teachers in Ekiti State, Nigeria. The

study focused on examining the influence of the dimensions

of organizational justice on job satisfaction and job

performance among teachers in Ekiti State. The descriptive

survey design was employed and data were collected

through questionnaire. Two hundred and fifty eight (258)

teachers randomly drawn from Ekiti State public schools

participated in the study. Four hypotheses were tested using

the independent t-test and the two way Analysis of Variance.

Results showed that organizational justice significantly

influences job performance among teachers in Ekiti State.

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1048

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

Also, it was revealed that job satisfaction significantly

influenced job performance among teachers. However, no

significant interaction effect of job satisfaction and

organizational justice was found on employee performance.

Result of data analyses also showed that sex has no

significant influence on employee performance among

teachers in Ekiti State. The study recommended that

teachers should be given responsibilities and authority with

less supervision to boost their sense of belongingness,

respect and commitment which sustains justice in

organizations and enhance performance.

Baghini, Pourkiani, and Abbasi (2014) conducted a study on

the relationship between organizational justice and

Productive behaviour of staff in Refaah bank branches in

Kerman City. To analyze the collected data, the descriptive

statistics and Pearson’s correlational test were used. Results

show that there is a significant relationship between

components of organizational justice and productive

behavior of staff in Refaah bank branches in Kerman City.

Ajmi (1998) investigated the analysis of the relationship

between organizational loyalty and workers’ feelings with

organizational justice in banking sector in India. The

objective of the study was to examine the relationship

between organizational loyalty and employees’ perception of

procedural justice and distributive justice in banking sector

in India. The study employed survey research design with a

sample of 117 employees selected from 24 banks in India.

The data were collected through questionnaire and

Correlation and regression were used for the analysis. The

study found that there is a low feeling with procedural

justice, all the workers have a feeling of inequity in the

application of laws and administrative decisions, as well as

the low feeling in distributive justice which do not relate

with organizational loyalty. The study recommended that

managers should apply laws and administrative decisions as

they relate to organizational justice to avoid the feeling of

inequity among employees in the same job cadre in order to

enhance organizational loyalty in the banking sector.

3. Methods

This study employed survey research design to collect

primary data through administration of instrument of

questionnaires to respondents drawn from selected

universities from south-south of Nigeria. Information was

gathered from a cross-section of 400 respondents from

fourteen universities which comprised seven each of public

and private in the region. Data were analysed using factorial

analysis of variance technique with the aid of statistical

package for social sciences (SPSS) version 20 to determine

the relationship between distributive justice and academic

staff performance among the universities in the south-south

of Nigeria.

4. Data Presentation and Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as frequencies and percentages will be used in answering the research question. This hypothesis is

tested using the factorial analysis of variance to find the level of differences between interactional justice and academic staff

performance among the universities in the south-south of Nigeria. All the 400 copies of questionnaire distributed were

properly completed and returned. Thus, the return rate is 100%. Therefore 400 respondents that participated in the study

were used in the analyses.

Table 1: Respondent Biodata

Responses Response rate Frequency

Male

289

Female

111

Total

400

Age

26-35yrs

97

36-45yrs

110

46-55yrs

87

Above 55yrs

106

Marital Status

Single

45

Married

330

Divorced

25

Total

400

Educational Qualification

B.Sc/HND

10

MBA/M.Sc

40

Ph.D

310

Total

400

Working Experience

Below 1yr

11

2-6yrs

107

7-11yrs

96

12-16yrs

95

Above 16yrs

91

Total

400

Source: Field Survey, (2020).

Category

Gender

Percentage

72.3

27.7

100

24.3

27.5

21.7

26.5

11.3

82.5

6.3

100

2.5

10.0

77.5

100

2.7

26.7

24.0

23.7

22.7

100

In all, respondents from government institutions accounted for 54.3% of the entire respondents.

Table 1 presents a summary of the responses on the distribution of respondents into their various categories of gender, age

bracket, marital status, educational qualification and working experience,.

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1049

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

Gender Distribution: Table 1 indicates that 289 respondents (72.3%) are males, while 111 respondents (27.7%) are females.

This indicates that there are more male lecturers in the selected tertiary institutions examined than there are female lecturers.

Age Bracket Distribution: Table 1 indicates that 97 respondents (24.3%) are within the age bracket of 26-35 years of age;110

respondents (27.5%) are within the age bracket of 36-45 years of age, 87 respondents (21.7%) fall within the age bracket of

46-55 years, the remaining 106 respondents (26.5%) is above 55 years of age. This indicates that greater portion of academic

staff is within the age bracket of 36-45 years.

Marital Status Distribution: Table 1 indicates that 45 respondents (11.3%) are singles, 330 respondents (82.5%) are married

while 25 respondents (6.3%) are divorced. This implies that there are more married academic staff than there are academic

staff that are still single and divorcees.

Educational Qualification: Table 1 shows that the number of respondents with B.Sc/HND is 10 constituting 2.5%, MBA/M.Sc

is 40 (10.0%). PhD has 310 (77.5%). From the Table, the respondents that has PhD has the highest percentage. It is

understandable because of the necessity of PhD in the University teaching profession.

Working Experience: Table 1 shows the number of years that the respondents have put in the industry. Experience is

important to the study because people that are new in the industry may likely not provide the right answers to questions posed

in the questionnaire. The Table shows that respondents that have spent between 7-11 years in the industry are highest in

number with 96 respondents constituting 24.0% of the entire respondents followed by people that have spent between 2-6

years 107 (26.7%). Respondents that have spent below 1 year are 11(1.8%), respondents that have spent between 12-16 years

are 95, constituting 23.7%, while those that have spent above 16 years are 91 (22.7%). The Table shows that most of the

respondents have spent reasonable number of years in the Universities to adequately evaluate and appropriately rate their

experiences in the Universities.

Scale Items

When decisions are made

about my job, the head always

considers my interest

When decisions are made

about my job, the head

considers my personal needs

with the greatest care.

My head explains clearly any

decisions if it is related to my

job.

I receive cordial working

relationship from my HOD and

colleagues

I can confidently say that my

institution keeps my interest in

mind when making decisions.

Valid N (listwise)

Table 2: Interactional Justice Descriptive Statistics

Federal

State

Std.

Std.

N

Mean

N Mean

Deviation

Deviation

Private

N

Mean

Std.

Deviation

263

3.83

1.06

76

3.72

1.09

285

3.64

1.10

263

3.77

1.09

76

3.71

1.11

285

3.72

1.12

263

3.83

1.10

76

3.80

1.05

285

3.62

1.11

263

3.82

1.08

76

3.76

1.07

285

3.69

1.13

263

3.84

1.11

76

3.64

1.03

285

3.66

1.11

263

76

Source: Field computation, (2020).

285

Table 2 shows the mean and standard deviation responses on the difference level of application of interactional justice applied

by management in dealing with academic staff. On the issue of whether academic staff believe that when decisions are made

about my job, the head always considers their interest, the federal university has a mean score of 3.83 while the standard

deviation is 1.06; states university has a mean score of 3.72 and standard deviation is 1.09 while the private university has a

mean score of 3.64 and standard deviation of 1.10 which is accepted. Also the idea whether the academic staff in their

respective Universities believe that when decisions are made about their jobs, the heads consider their personal needs with the

greatest care the federal university has a mean score of 3.77 and the standard deviation of 1.09; states university has a mean

score of 3.71 and standard deviation is 1.11 while the private university has a mean score of 3.72 and standard deviation of

1.12 which is accepted. On the assertation whether the academic staff feel that their heads explain clearly any decisions if it is

related to their jobs, the federal university has a mean score of 3.83 and the standard deviation of 1.10; states university has a

mean score of 3.80 and standard deviation is 1.05 while the private university has a mean score of 3.62 and standard deviation

of 1.11 which is accepted. On the idea to ascertain whether academic staff feel that they receive cordial working relationship

from their HODs and colleagues, the federal university has a mean score of 3.82 and the standard deviation of 1.08; states

university has a mean score of 3.76 and standard deviation is 1.07 while the private university has a mean score of 3.69 and

standard deviation of 1.13 which is accepted. Finally, on the idea to ascertain whether academic staff believed that they can

confidently say that their institution keeps their interest in mind when making decisions the federal university has a mean

score of 3.84 and the standard deviation of 1.11; states university has a mean score of 3.64 and standard deviation is 1.03 while

the private university has a mean score of 3.66 and standard deviation of 1.11 which is accepted. The mean scores show that

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1050

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

academic staff from both universities perceived the level of informational justice to be high in their universities, with a mean

score above 3.5 in 5 points scale.

Table 3: Lecturer Student Relationship Descriptive Statistics

Federal

State

Private

Scale Items

Std.

Std.

Std.

N

Mean

N Mean

N

Mean

Deviation

Deviation

Deviation

I feel i am close to my

263

3.69

1.07

76 3.81

1.09

285

4.10

.96

students and i can trust them

I get along with my students

263

3.70

1.09

76 3.85

1.01

285

4.12

.89

to a large extent

What i teach at school is really

263

3.60

1.13

76 3.81

1.11

285

4.14

.89

interesting to my students

I am willing to invest more

time for all the courses due to

263

3.65

1.10

76 3.85

.99

285

4.13

.95

the favourable feedback i get

from my students

I am satisfied with the

263

3.66

1.15

76 3.78

.97

285

4.19

.90

performance of my students

Valid N (listwise)

263

76

285

Source: Field Computation, (2020).

Table 3 shows the responses of that sought to assess the level of lecturer-students’ relationship in the studied Universities. On

the issue on whether academic staff feel they are close to the students and can trust them, the federal university has a mean

score of 3.69 while the standard deviation is 1.07; states university has a mean score of 3.81 and standard deviation is 1.09

while the private university has a mean score of 4.10 and standard deviation of 0.96 which is accepted. Also the idea whether

the academic staff believe that they get along with my students to a large extent, the federal university has a mean score of 3.70

and the standard deviation of 1.09; states university has a mean score of 3.85 and standard deviation is 1.01 while the private

university has a mean score of 4.12 and standard deviation of 0.89 which is accepted. On the assertation whether the academic

staff feel that what they teach at school is really interesting to their students, the federal university has a mean score of 3.60

and the standard deviation of 1.13; states university has a mean score of 3.81 and standard deviation is 1.11 while the private

university has a mean score of 4.14 and standard deviation of 0.89 which is accepted. On the idea to ascertain whether

academic staff believe that they are willing to invest more time for all the courses due to the favourable feedback they get from

the students, the federal university has a mean score of 3.65 and the standard deviation of 1.10; states university has a mean

score of 3.85 and standard deviation is 0.99 while the private university has a mean score of 4.13 and standard deviation of

0.95 which is accepted. Finally, on the idea to ascertain whether academic staff believe that they are satisfied with the

performance of their students, the federal university has a mean score of 3.66 and the standard deviation of 1.15; states

university has a mean score of 3.78 and standard deviation is 0.97 while the private university has a mean score of 4.19 and

standard deviation of 0.90 which is accepted. The mean scores show that academic staff from both universities perceived high

level of lecturer-student relationship in their universities, with a mean score above 3.5 in 5 points scale. Interestingly, private

university has the highest mean score (4.00). It therefore seems that academic staff working in private universities have more

cordial relationship with their students more than those in both Federal and State Universities.

4.1. Test of Hypothesis

Test of Hypothesis One

HO4 : There is no level of variation in interactional justice in relation to lecturers-students’ relationship between academic staff

in public and private universities in South-south Nigeria.

HA4 : There is level of variation in interactional justice in relation to lecturers-students’ relationship between academic staff in

public and private universities in South-south Nigeria.

Table 4: Tests of Difference between Interactional Justice and Lecturer-Students’ Relationships

Dependent Variable: Lectstudent Relations

Type III Sum

Mean

Partial Eta

Source

Df

F

Sig.

of Squares

Square

Squared

a

Corrected Model

137.690

33

4.172

6.062

.000

.253

Intercept

2151.350

1

2151.350

3125.503

.000

.841

Students’ Relationship

39.844

2

19.922

28.943

.000

.089

Interactional Justice

Public/Private universities

*Interactional Justice

Error

Total

Corrected Total

@ IJTSRD

|

4.170

11

.379

.551

.868

.010

13.258

20

.663

.963

.506

.032

406.110

9104.870

590

624

.688

543.800

623

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1051

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

a. R Squared = .253 (Adjusted R Squared = .211)

a. R Squared = .253 (Adjusted R Squared = .211)

(I) Public/private

university

Federal

State

Private

(J) Public/private

university

Mean Difference (I-J)

Std. Error

Sig.

State

Private

Federal

Private

Federal

-.6203*

-.9306*

.6203*

-.3104*

.9306*

.10805

.07094

.10805

.10711

.07094

.000

.000

.000

.001

.000

State

.3104*

.10711

.001

Hypothesis four was also tested using factorial analysis of variance. The variables understudy in the universities (Federal, State

and Private) were interactional justice as the independent variable and lecturer-students’ relationships as dependent variable.

The result is presented in table 4, the model fit was established (F = 28.943, P < 0.000). The result shows a significant

association between the universities and lecturer-students’ relationship ( F = 0.551, P < 0.868). In other words, the level of

lecturers’ students’ relationship depends on whether the university is public or private. Interactional justice is significantly

associated with lecturer students’ relationships. Similarly, the interaction between university status and interactional justice

produced a significant effect on lecturers’ students’ relationship among the universities in the South South, Nigeria (F = 0.963, P

< 0.506).

The examination of partial Eta square shows that the proportion of variance due to between group are 0.089, 0.010, and 0.032

for private/public universities, interactional justice, interaction between private/public universities and interactional justice

respectively. Thus, the effect is small and corroborated by R2 (R-Square = 0.117 or 11.7%).

The evaluation of pair wise mean differences shows a significant difference mean score of lecturer students’ relationship in

public universities and private universities (Federal and private P < 0.001, State and Private P < 0.021). From the result

presented in table 4, we accept the alternate hypothesis which states that there is level of variation in interactional justice in

relation to lecturers-students’ relationship between academic staff in public and private universities in South-south Nigeria.

4.2. Results

The result of the test revealed that the mean scores of

interactional justice are also close. It shows that Federal has

3.82 mean score, 3.73 for state and 3.67 for private

universities while the mean scores on the level of lecturerstudent relationship in the federal, state and private

universities are 3.66; 3.82 and 4.13. These showed that the

level of lecturer student relationship is at its best since the

results seem to cut across both public and private

universities as the differences among the mean scores seems

negligible. In the hypothesis the result shows that there is a

level of variation in interactional justice in relation to

lecturers-students’ relationship between academic staff in

public and private universities in South-south Nigeria, (F =

28.943, P < 0.000). Interactional justice is significantly

associated with lecturer students’ relationships (F =0.551, P

< 0.868). Similarly, the variation of academic staff on

interactional justice produced a significant effect on

lecturers’ students’ relationship among the universities in

the South South, Nigeria (F =0.963, P < 0.506).

The examination of partial Eta square shows that the

proportion of variance due to (between) group are 0.089,

0.010, and 0.032 for university management interactional

justice, lecturer-student relationship and interactional

justice perception by lecturers respectively. Thus, the effect

is small and corroborated by R2 (R-Square = 0.117 or

11.7%). The evaluation of pairwise mean differences shows

a significant difference mean score of lecturer students’

relationship in public universities and private universities

(Federal and private P < 0.001, State and Private P < 0.021).

From the result, we accept the alternate hypothesis which

states that there is a level of variation in interactional justice

@ IJTSRD

|

Unique Paper ID – IJTSRD30205

|

in relation to lecturers-students’ relationship between

academic staff in public and private universities in Southsouth Nigeria.

This finding implies that there is a significant variation in

interactional justice in relation to lecturer students’ between

academic staff in public and private universities in South

South, Nigeria. In congruence with the results of this

hypothesis as supported by Hoy and Miskel, (2005); Fox

(2008) found that a positive interactive justice makes the

school a good place to be, a satisfying and meaningful

situation in which lecturers spend a substantial portion of

their time relating and discussing academic issues with their

students.

5. Conclusion and Recommendation

5.1. Conclusion

This study explores academic staff perceptions toward

organizational justice and how it varies between academic

staff in public and private universities in South-South,

Nigeria in terms of commitment, subject knowledge,

communication skills and lecturer-student relationship. In

the course of this study, theories and empirical literature

were reviewed, data were collected and tested. From the

research it is ascertained that organisational justice led to

different variation of academic staff performance between

public and private universities in South-South, Nigeria.

These results build on the work of previous researchers who

demonstrated that organizational justice influences

academic staff performance through different behaviours.

This clearly shows that when perceived organisational

justice exist in the university environment, there is the

generation of strong feeling of obligation towards their

respective institutions and academic staff become more

Volume – 4 | Issue – 2

|

January-February 2020

Page 1052

International Journal of Trend in Scientific Research and Development (IJTSRD) @ www.ijtsrd.com eISSN: 2456-6470

committed to their job. Therefore, it can be deduced that

equitable distribution of resources, fair procedures for job

decisions, with appropriate allocation of resources and fair

communication of decisions will result in high academic staff

performance toward higher academic excellence.

5.2. Recommendation

On the basis of the findings and conclusion drawn from the

study, the following recommendation is made.

1. Management of Nigerian universities should come out

with supportive policies as a way of promoting

interactional justice toward maintaining lecturerstudent relationship which can be done through

integrating the philosophy of target education

programme established in 1990 by Aumua and Drake

(2002) and the French Intervention programme

(Chouinard, 2004-2005, CLASSE) which will both give

practical tools to favour respective and harmonious

Lecturer-Student Relationship as well as to enhance

achievement of academic staff performance through

organizational justice.

References

[1] Ajala, S. T. A. (2000). A study of factors affecting

academic performance of students in selected federal

and state secondary schools in lagos state. Unpublished

M. Ed. Thesis, University of Lagos.

[2] Ajmi, Mensah (1998) ‘‘Vigilante homicides in

contemporary ghana,’’ Journal of Criminal Justice, 3(3),

413–427.

[3] Aluja-Fabregat, A., Balleste-Almacellas, J., & TorrubiaBeltri, R. (1999). Self-reported personality and school

achievement as predictors of teachers perceptions of

their students. Personality and Individual Differences,

27, 743–753.

[4] Auma, S. & Drake J. (2002). Management information

system; A global perspective: Makurdi: Oracle Press.

[5] Babad, E. (1993). Measuring and changing

teachers’differential behavior as perceived by students

and teachers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82,

683–690

[6] Baghini, S.P, Pourkiani .S & Abbasi, J. (2014). A new

look at psychological climate and its relationship to job

involvement, effort and performance. Journal of Applied

Psychology, 81, 358-368.

[7] Balyen, H.S. (2012). Note on the concept of

commitment. American Journal of Sociology. 4(66), 3240.

[8] Bernardin, H.J. (2010). Human resource management:

An experimental approach, 5th Ed. New York: McGrawHill.

[9] Bies, R. J. & Moag, J. S. (2008), “Interactional justice:

communication criteria of fairness”. In Lewicki, J. J.,

Sheppard, B. H. & Bazerman, M. H. (Eds) Research on

Negotiation in Organisations 1 (2) 43-55. JAI,

Greenwich, CT.

[10] Bies, R. J. (2008). Identifying principles of interactional

justice: The case of corporate recruiting. In Bies, R. J

(Chair), Moving beyond equity theory: New directions in

research on justice in organisations. Symposium

@ IJTSRD

|