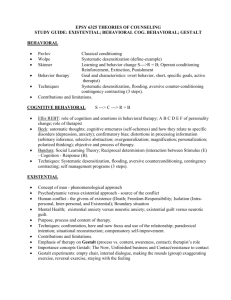

Existential Therapy Vos, Cooper et al. article Compared to other psychotherapies, little research is conducted on existential therapies and most of the available studies use a qualitative or phenomenological method and/or describe only one case o This may be explained by the underlying existential philosophy that “existence precedes essence” o That is: we should not speak in reductionist terms and scientific labels but focus on the client’s subjective lived experience and on what reveals itself as truth in the therapeutic relationship However, our practices are embedded in a world where health insurances and governments expect to see quantitative research as justification for financing mental health care o ET follows a ‘coherence theory of truth’ o This epistemology implies that all scientific methods are insufficient to describe the totality and subjectivity of a clients lived experience, as the client’s reality is not directly accessible by instruments, calculations and observations o Existential concepts are difficult to study and operationalize ET concepts emphasize that the validation, justification and improvement of therapies can and should only be developed in client-centered ways, for instance by focusing on the client’s selfreflection, the therapeutic relationship and the therapist’s own development Clinical Model o ET does not have one unified clinical model o Some therapists see the identification of clinical concepts as “labelling” and burdening clients with psychopathological diagnosis from which they need to be cured Opposes the existential assumption that the client’s subjectively lived experience is irreducible to any label or diagnosis and that the problems of the client often have to do with universal problems in living that need to be accepted and faced o Authors asked leading ET psychotherapist to discuss their implicit understands and definitions of ET. Although consensus was not achieved, several assumptions were frequently reported and developed into an existential model of clinical distress o Assumes that there are ‘givens of existence’ which define the phenomenological reality of clients, such as our human capacity for freedom and choice, being embedded in relationships with others and our world and inevitably facing limitations and challenges o Assumes that clients immediately understand these ‘givens of existence’ as they have a primary subjective phenomenological flow of experiencing their daily life world o o o o Only secondarily, they may give meaning/interpretation to these experiences and thus cover the primary experiences of these givens The primary experience of life’s givens has often been described in terms of existential moods, such as death anxiety, existential guilt, isolation, urgency, absurdity, boredom and vacuum o Existential moods differ from emotions and psychopathology, as they do not have a specific object or meaning but regard a primary unstructured experience of existence-as-such For instance, is there any sensible way to measure these constructs Assumes that individuals have the freedom to either authentically accept these existential moods and face these givens (“uncover reality”) or to inauthentically deny or avoid these (cover reality) Many individuals respond w/ existential defense mechanisms in confrontation with the bare givens of their existence such as mortality – through denial, avoidance, re-interpretations – shifting their attention to what is meaningful in their life Assumes that individuals are oriented to, driven or motivated by existential ‘ needs’ ; and they seem to function more effectively when these are fulfilled, for instance by actualizing their human potential and taking responsibility for their choices Meaning in life has often been described as crucial for optimal human functioning Assumes that individuals may differ in how they cope with the givens of existence, due to differences in existential skills and life experiences Such individual differences can be seen regarding the important skill of accepting our primary experiencing, life’s givens and life’s irresolvable tensions and paradoxes o The latter implies that clients have the capacity to develop a ‘dual attitude;: simultaneously accepting life’s possibilities/freedom/responsibility and its limitations Research from pilot studies suggests that only 70% of people have this skill At later age, it may be possible to develop a dual attitude, for instance in psychotherapy Intervention studies demonstrate the possibility of learning to tolerate existential moods, be flexible, and simultaneously commit to daily life and accept life’s givens Assumes that ineffectively coping with life’s givens may result in psychological distress and requesting psychotherapeutic intervention For instance, individual may ask questions about life leading to a crisis or demoralization, regarding meaning of life, spirituality/religion, identity and existence Existential concerns and not merely psychopathology may explain the request for psychotherapeutic help in individuals, especially in boundary situations in life – e.g. being diagnosed with a fatal health condition, after a divorce, entering retirement, etc. Therapeutic Model o Organized into three overarching domains, crossing the difference b/w particular existential schools: phenological practices, relational practices and practices informed by existential assumptions Phenomenological practices focus on the client’s subjective flow of experiencing, to do just to the totality of the client’s inner experiences and help them gain deeper self-awareness and insight This includes adopting of an “understanding stance towards the client” o Possibly associated with Roger’s person-centered practice of empathy Relational practices focus on establishing an in-depth, authentic therapeutic relationship with clients; along with reflection, on and analysis of the relational encounter Four main relation categories in ET 1. Adopting a relational stance (e.g. being present, caring, authentic) 2. Addressing what is happening in the therapeutic relationship (being aware of one’s reactions to the client, self-disclosure) 3. Relational skills (therapeutic listening) 4. Person-centered skills (equal power relationship, unconditional positive regard) Aside from ET, empirical research strongly supports the emphasis on the quality of the therapeutic relationship, with APA Task force concluding that “the therapy relationship makes substantial and consistent contributions to psychotherapy outcomes independent of the specific type of treatment Practices informed by existential assumptions involves explicitly addressing life’s givens, such as freedom, choice, responsibility, being-inthe-world, mortality, existential anxiety and uncertainty of being Explicitly exploring the client’s worldviews, their ways of relating to life and their authenticity ET can be effective for clients with a particular strong wish to speak explicitly about existential topics such as cancer patients and those in palliative care contexts This may be explained by the fact that negative life events, such as physical suffering often elicit explicit existential concerns Such events seem to shatter the fundamental positive illusions that many people have in daily life for instance that they are invulnerable, immortal and in control and that life is just and understandable Despite serious limitation such as small number of studies, some clients may significant benefit from certain types of ET Particularly clients in boundary situations in life may benefit from meaning-oriented group therapies ETs have similar or slightly larger effects than other nonexistential psychotherapeutic interventions for cancer patients such as cognitive-therapy and mindfulness Few studies about clients without physical diseases; the existing studies in physically health samples suggest small, non-significant effects Existential Therapy: 100 Concepts What is existentialism? o Ultimately existentialism concerns itself simply with what it is to exist as a human being. It is a philosophical approach to understanding our experiences, our world, our relationships and this thing we call our ‘self’. It doesn’t deny the validity of natural science, but makes the point that human beings cannot be fully understood in terms of it. Human existence can be understood only through a thorough examination of our experience of what it means to be (Heidegger, 1978) and through an understanding of the universal issues we face in being human, including freedom, responsibility, meaning, isolation, death and anxiety. Historical backgrounds, philosophical foundations o The roots of existential therapy lie in 3,000 years of philosophy and, in particular, in o o the human quest to understand life and overcome adversity (Deurzen, 2007). These roots encompass the wisdom of the Ancient Greeks, incorporating tenets of Eastern philosophies such as Buddhism and Taoism and taking inspiration from the work of an eclectic mix of philosophers, writers, artists and theologians. Existential philosophy -it was a philosophy that emphasised human individuality, freedom and responsibility, and encouraged resistance to systems of thought that sought to control, or to reduce the complexity of human existence to a set of laws, rules or statistics Often described as a study of things as they appear, phenomenology was originally developed by the German mathematician Edmund Husserl (1859– 1958). Husserl rejected the idea that truth was to be found solely in objective, natural science and instead proposed a method of studying human experience that acknowledged both the objective and the subjective. What phenomenology aims to do is reveal things as they actually are by studying them in a way that removes the assumptions and preconceptions that limit our understanding of the o Existential psychotherapies, including Daseinsanalysis, Logotherapy, and the therapies that make up the American and British schools of existential therapy, each bring their own particular blend of ideas from existential philosophy and phenomenology and present credible alternatives to therapies based on the dominant medical model of mental health. o The basis of an existential approach to therapy o Unlike other forms of psychotherapy, which take their inspiration primarily from psychology or medicine, existential therapy is philosophy-based. o The existential therapist recognises that we all face certain universal conditions and o o o o o that the differences between us come down to how we choose to respond to these conditions. Existential therapy focuses on this uniqueness – resisting the tendency to place people in boxes or typologies according, for example, to their personality, age, gender, educational background, behaviour, sexual preferences, political views or choice of lifestyle. It is therefore a ‘non-pathologising’ therapy, in which a very wide range of human thought, behaviour and emotion is considered normal, and where terms like ‘diagnosis’, ‘illness’ and ‘symptoms’ and the medical model of mental health are seen as largely unnecessary and potentially harmful, restricting both our understanding of their world and the sense of responsibility and freedom with which we approach our challenges. clarifying their worldview, their values and beliefs, and the attitude they take to their world, and to the people and events they encounter. Illuminating these stances leaves the client free to consider whether or not these ways of being, thinking, feeling and behaving will best help them live a life in line with their values, a life that is meaningful, a life in which they engage actively with the choices they make and strive to make them in light of their own needs and the needs of others. The existential therapist recognises that we are good at deceiving ourselves and that this ability to rationalise, ignore or underestimate the significance of evidence that contradicts what we want to believe can often make us strangers to ourselves, standing in the way of our ability to truly know our reality. As a result, we may refuse to see how we, or other people, are contributing to our unhappiness, distress or lack of fulfilment, perhaps because we are frightened of what we might lose, or how we might have to change if we were to open our eyes. Clients are invited to describe and examine their behaviours, relationships, thoughts and ideas and encouraged to be open to those alternative ways of thinking, behaving and being that they are not currently choosing. Existential therapy is not necessarily about major change (though for many clients it leads to new and profound ways of being). A client may decide to make some, or even many, changes in their life, or they may decide not to make any outward changes at all. Often the inward changes in emotions, attitudes and ideas are enough to allow them to move forward and deal with any challenges they are facing. Although existential ideas are relevant to everybody, existential therapy is not a flavour of therapy that everyone finds palatable (Tantam, 2002). It demands much of clients, who must be prepared to wrestle with, and ultimately come to accept, the dilemmas and paradoxes of human existence, to take responsibility for the choices they make (and the consequences that result from them) and to confront absurdity, meaninglessness and the finitude of their own existence with courage and tenacity. Existential Therapy Here and Now o Over the last ten years, the number of schools of existential therapy around the world together with the number of practicing existential therapists has grown rapidly o Reflects the continuing dominance of the British School of Existential Therapy in the development and promotion of existential theory and practice o Types of existential therapies and representation per region: o The Universals of Human Existence o The universals of human existence are the conditions that pertain to every human o o o o life, across all cultures, and across all époques. These conditions are often referred to as ‘givens’, or the ‘existentials’ Philosophers and practitioners focus their enquiries on different existential universals, making it difficult to establish a definitive list. However, almost all those that hold an existential perspective agree on these fundamental givens: freedom, temporality, facticity, which is also known as ‘throwness’ (Heidegger, 1972) (the specifics of our situation that are beyond our choice, e.g. the place of our birth, the fact of suffering and death), choice, death, uncertainty, isolation and relatedness, meaning and meaninglessness, guilt and anxiety. Each and any of these givens have implications for the others; it is difficult to even speak of one aspect without referring to the others. These dimensions of human existence are inescapable: they affect everyone, all the time. Although at particular times in our clients’ lives one concern may seem to be in the ‘foreground’, or the dominant aspect of their focus, in reality, all the other givens are in attendance. What is valuable about the existential therapist’s perspective on universals or givens is that they recognise that although these givens are inevitable, how any of us respond to these is a matter of choice. Existential therapists do not impose a value judgement on such responses. Instead they provide a space where their clients can explore their reaction to the different universals and consider a full range of alternative stances. Existence Precedes Essence o When Sartre coined the phrase ‘existence precedes essence’ he was reminding us o o Daseinanalyis – represents ET from Canada, Greece, Switzerland, Austria and Brazil In Europe, Daseinalysis and Logotherapy (meaning focused) dominate In the US, existential-humanistic therapy is preeminent, largely because of the popularity of the leading proponent Victor Yalom There are many challenges facing existential therapists today – including how to explain and teach an approach that has been inspired by such a diverse range of thought, and that takes an epistemological stance that resists systematisation, indeed considers it to be the antithesis of good practice. that just as there are an infinite number of ways of being a table, there is no predetermined pattern, set of ideal characteristics or ‘essence of human being’, that we need to fit into. For the existentialist, a human being is not a clearly defined object, or an essence that can be totalised, finalised or perfected. There is no ‘human nature’ that defines us. Therefore we cannot seek to understand another by slotting them into convenient typological boxes in the form of personality types, levels of intellect, groups of medical symptoms or astrological signs. In the therapeutic setting, these classifications serve only to hide the uniqueness of the individual by encouraging both parties to make assumptions about the client, thereby restricting that individual’s awareness of her freedom to change. When clients seek to categorise themselves – ‘I am a depressive’, ‘I have my father’s personality’ – the existential therapist will be curious as to how and why they have chosen to identify these things as part of the ‘essence’ of who they are and what the implications of these choices are for that individual. Four Worlds: Physical, Personal, Social and Spiritual o Many existential therapists use this model as a basis for thinking about and exploring their clients’ worldviews. Deurzen-Smith (1995, p9) suggests that when clients describe their experience of each of the worlds in detail they gain insights into how they see the world and their place within it and ‘become truthful with themselves again’. The Umwelt or physical dimension refers to embodiment and the physical environment. This is the most fundamental of the dimensions, as we cannot be human without having a physical presence, and without being affected by the elements in our environment, Key polarities within this dimension include birth versus death and expansion versus contraction of the physical world. The Mitwelt or social/public dimension comprises everyday social interactions; this would include our attitudes towards public constructs such as race, gender, class or family, for example. It would also include ways in which we relate to others, and contains polarities such as trust versus distrust, competition versus cooperation and conformity versus individualisation. The Eigenwelt or personal/private dimension is that which reflects our attitudes and assumptions about the intimate others in our lives, as well as the view that we hold of ourselves. This is the dimension we most commonly associate with counselling, as it involves the person’s relationship to his or her self and to family, close friends, etc. (Deurzen & Kenwood, 2005). In this context we may discern how the client values, or devalues, themselves, as well as the meaning and attitudes they hold with reference to their closest friends and family. Polarities in this dimension include self-acceptance versus selfdevelopment and authenticity versus inauthenticity. The fourth dimension is the Überwelt or spiritual dimension , which includes our assumptions and perspectives on the world, the universe and the cosmos. Here we find our philosophical and spiritual values and assumptions about life, and the sphere beyond. Polarities within this world include meaning versus meaninglessness, good versus evil and transcendence versus mundanity. These dimensions are inter-connected and crossreferential, in much the same way as the givens of existence: it is difficult to consider one without implicating the others. This model is a structure by which we can begin to understand our own and others’ worldview. It helps the therapist to stand back from the client’s day-to-day concerns and ensure that all the different aspects of their reality are explored (Cooper, 2003). Where there is an emphasis on one dimension in a person’s concerns, or when there is a paucity of reference to any particular category, these imbalances are suitable focal points for reflection and exploration o The Foundational Elements of an Existential Therapeutic Relationship o The initial meeting between client and therapist continues the process of ‘co-creating’ o o the therapeutic relationship that started as soon as initial contact was made. As Cohn (1997, p33) points out: The client you meet as the therapist is the client who meets you. There is no client as such. If two therapists meet the same client, it is not the same client. It is advisable to notice the quality of relationship that has already begun, even before the first meeting: what impressions linger, what assumptions are in play. The phenomenological method can provoke reflection and assist in clarifying and bracketing pre-judgements and suppositions. The client’s worldview begins to unfold at the first utterance: the narrative reveals the significant relationships and issues that are currently demanding their attention. Role of the therapist o The existential phenomenological stance regards each client as individual and each therapeutic encounter as unique. Unsurprisingly, therefore, existential therapists are concerned that articulating ‘a way of being a therapist’ will result in the application of an approach to working with clients that is rigid and manualised. o Some forms of existential therapy are more explicit about the role of the therapist, than others. Deurzen, for example, describes the therapist as a ‘mentor’ or ‘wise person’ who brings a special wisdom and experience to the client’s reflections (Cooper, 2003). In Logotherapy, therapists are expected to take charge of the therapeutic process, while therapists influenced by R.D. Laing (1960) will allow the client to structure the session. In Daseinsanalysis, the therapist may focus on the client’s maladaptations and dysfunctional ways of being, while therapists who share the philosophy of the anti-psychiatry movement might look for the intelligibility and purposefulness of the client’s symptoms (Cooper, 2012). o What is true in all forms of existential therapy is that the role of the therapist will reflect the aims of therapy and the therapist will start by facilitating an exploration of the client’s lived experience, that is, her ‘worlding’ as represented by her worldview. o In a joint enterprise, the therapist and client work to clarify the values and assumptions integral to the client’s worldview. o The emphasis is on ‘being with’ the client: this is in the service of establishing a relationship in which the client can more readily and freely describe their lived experiences. Existential practitioners do not aspire to cures, or even changes in behaviour: rather, they provide a relationship that offers the opportunity for the client to reflect on the nature of their own difficulties, and possible alternative ways of responding to their possibilities of being-in-the-world. o the practitioner must resist attempts to be drawn into suggesting particular changes or remedies to the client’s difficulties. Role of the client o Each client must come to find their own, personal way of being in the world and must choose for himself or herself how to face both the universal and the unique challenges their journey presents. o On those occasions when a significant understanding or shift in perception occurs, it is useful to reflect what has happened, and how it has been a consequence of the client’s willingness to reflect and explore, providing further demonstration as to how the participation of both therapist and client serves the aims of therapy. Additionally, when there are meetings in which the client does not feel inclined to participate, this too should be viewed by the therapist as an opportunity to discover with the client what is impeding their engagement; this, again, can illustrate to the client that the quality of the engagement, as well as that of the therapy, is, in part, a consequence of their own contribution. Finally, it is the role of the client to determine if the therapy is useful; in fact, it is their obligation. If there is an educative element to the therapy, it is in the appreciation of how reflection can clarify, to some extent, the basis on which the client chooses to live their life.