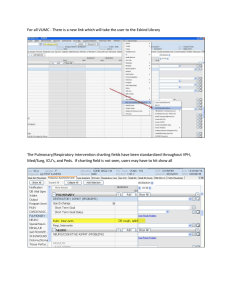

MEDICAL NOTE WRITING TIPS Overview • Effective written communication covers areas such as explanations for referrals, interpreting lab results, and clear and contemporaneous documentation of patient visits. o Your charts must explain the reasoning behind treatment decisions. o If the physician’s diagnosis is questioned at some point in the future, and the documentation reflects a thoughtful and systemic approach to arriving at a diagnosis, then the doctor is more likely to be seen as being reasonable in their approach rather than negligent for missing a diagnosis • Documentation is not merely “record keeping”; the documentation that comprises a patient’s medical record is also a legal document. Documentation is therefore a means for others to assess whether the care that a patient received met professional standards for safe and effective medical care, or not. • “If it wasn’t documented, it wasn’t done.” o From a professional (and legal) standpoint, this is entirely true. In this sense, documentation is how we “prove” what we did (or didn’t) do in the course of caring for our patients. For this reason, documentation isn’t peripheral to your job as a provider, it’s central to it. • Document clearly and accurately. o Avoid abbreviations, acronyms, and medical jargon. Keep in mind that documentation may be read by patients and other individuals without clinical training. Not everyone may know that “HTN” means “hypertension,” that “WNL” means “within normal limits,” and that VSS means “vital signs stable.” Even other clinicians may disagree about the meaning of various terms and acronyms. Avoid confusion by spelling things out. o Dr. Singer does use abbreviations, but I prefer that we as a practice steer clear of them as much as possible. • Avoid vague terms and generalizations. When you document, be as clear and specific as possible. o For example, don’t use vague terms like “small” to describe a pressure ulcer (decubitous ulcer); instead, write something like, “stage II decubitous ulcer in sacral area, 1.5 cm width x 1 cm breadth x 0.5 cm deep; no drainage or tunneling present.” If you’re noting how much a patient ate, don’t write, “patient ate some of her meal.” Instead, write something like, “patient ate approximately 50% of food on lunch tray.” TBPI – 07/10/2020 1 If you’re unclear, others either won’t understand what you meant, or worse, may assume that for some reason you’ve deliberately omitted clinical information. • Document what you did or observed, not your opinion (this is different from the assessment portion of the note, where you are expected to include your professional opinion). One of the big no-no’s in medical documentation is to shade your charting with opinion, rather than stick to the facts. o For instance, you should never chart something like, “Patient uncooperative, will not take medications.” Instead, simply write, “Patient refuses medications.” The patient’s refusal of treatment should be documented, including the patient’s stated reason for refusal, if provided, and any action taken by the provider, as well as patient education and notifying the patient and their family. Patients who refuse to accept treatment recommendations might bear partial responsibility for a subsequent injury, which is known as “contributory negligence.” o If a patient is rude, inappropriate or even hostile, do not record those subjective judgments in your notes; instead write, “Patient made verbal threats toward myself and other staff members; per hospital’s safety protocol, security personnel called to patient’s room.” Whatever the circumstances, you should record observations, actions and events, not judge them. • Document care, not conflicts. o Just as you should avoid recording judgments about patients, you should avoid documenting disputes or conflicts between yourself and other medical professionals. For instance, if you were unable to give a medication because it was unavailable from the pharmacy, don’t write “medication not given because pharmacy could not provide it on time despite 3 follow-up phone calls.” Instead, write something like, “medication not given because it is currently unavailable from pharmacy.” (Better yet, note the facts of the challenge and what you did to overcome it; i.e., “medication not given because it is currently unavailable from pharmacy; discussed with Dr. Singer, and I will order alternate medication with equivalent therapeutic effects.”) We all face stress and sometimes conflicts at work; vent to your friends, not in your documentation. TBPI – 07/10/2020 2 • Only document care that you performed. o This may sound obvious, but it bears repeating nonetheless: never document observations you didn’t make, medications you didn’t give yourself, or care you didn’t actually perform. o Documenting care that you either didn’t perform, or care performed by someone else, is not only foolish and unethical, it’s fraudulent. Some oversights, and even errors, are inevitable in medicine, but dishonest documentation is unforgiveable and totally avoidable; develop good habits early in your career and avoid this unethical and illegal behavior at all costs. • Document in a timely manner. o In the course of a busy day, it’s not always possible to document right after you see the patient. Nonetheless, make an effort to document as soon after your examination of the patient as possible. Not only will your documentation tend to be more accurate, you’ll also avoid the time-management trap of leaving all of your documentation until the end of the day, when you’re usually tired and short on time (and often short on energy and patience as well). o Remember, documentation isn’t peripheral to your job as a medical provider, it’s central to it – and a legal requirement too. Get into the habit of documenting as early and as often as you’re able throughout your day. • Avoid spelling and grammatical errors. o While this isn’t the most important guideline to follow, correct spelling and grammar nonetheless matters. Not only are spelling and grammatical errors distracting, they also make your charting appear sloppy, unprofessional and possibly unreliable, especially if they are numerous. After all, if you can’t even be bothered to spell correctly, why should someone trust your ability to accurately and reliably deliver care? Remember that documentation is not for your eyes only; your charting is a part of a patient’s permanent medical record, which is also a legal document. Some typos and mistakes are inevitable, especially when things are moving fast, but do your best to minimize them. • Write or type legibly and professionally. o This piece of advice is along the same lines as using correct spelling and grammar in your documentation. After all, if someone can’t read your charting, it’s useless to you and to him or her. If you do computer charting (which is increasingly common), write in complete sentences, using a standard font, color and size. (Typing your notes in TBPI – 07/10/2020 3 purple, 16-point font is unprofessional and distracting). Don’t type in all caps, as this makes your writing more difficult to read and is analogous to ‘shouting’ with your writing. If you’re charting on paper, use only black or very dark blue ink, as other shades can be difficult to read and don’t photocopy well. Never use pencil, as this can smudge and is more difficult to read. • Correct mistakes appropriately. o It’s almost inevitable that you’ll make some mistakes as you document; that’s not a problem as long as you know the right way to correct those mistakes. If you’re doing paper charting and you make a mistake, simply draw a line through your writing and initial beside it; don’t attempt to scribble over your writing, as this creates the appearance that you’ve attempted to hide or falsify your documentation. If you need to indicate that you’ve made a change, simply write “mistaken entry” and avoid using words like “error,” which can suggest that you made a medical error that jeopardized patient safety. Depending on the system your institution uses, if you’re doing computerized charting you’ll probably have both “save” and “sign” functions. The “save” function usually allows you to return to your charting or notes and make changes without any indication that you’ve done so; if you make a change after you’ve digitally “signed” your documentation, however, a notation that you’ve made a change will probably be indicated. That isn’t necessarily a problem, but do be aware of this; and again, if you’re prompted to provide a reason or indication for the change, use a phrase such as “mistaken entry,” rather than “error.” • Documentation is the most important at the most challenging times. o When things are going smoothly, there’s usually plenty of time to document in an accurate, detailed, and timely manner; when things aren’t going smoothly, there can hardly be enough time to document at all. But it’s precisely when things aren’t going well – for instance, after a code, or after a complex patient admission, discharge or transfer – that it is most important to document well. After all, what are the chances that someone will examine your charting if your patient faces no complications? Probably low. This predicament isn’t necessarily problem, but it is worth bearing in mind. Even if you’re exhausted or have to stay late to document after a challenging clinical encounter, it’s worth it because during these times clear, accurate and timely documentation is especially important. Even if things don’t go TBPI – 07/10/2020 4 well for your patient, if you’ve documented well you can protect yourself and the medical license you worked so hard to obtain. • Develop good habits. o Documenting well is sort of like brushing your teeth; it can be timeconsuming (and sometimes annoying), but if you’ve gotten into the habit of doing it – if it’s an almost automatic part of your day – then it’s much more likely you’ll do it consistently and well. As you gain experience and confidence, it can be tempting to let the quality of your documentation slip. If no one’s ever questioned or audited your charting (at least to your knowledge), you may even mistakenly convince yourself that documentation isn’t important after all. Don’t fall into that trap. When you let your documentation slip, you jeopardize yourself and your license, and beyond this, you make it much more likely that you’ll forget to document (or fail to document well) after a challenging clinical encounter when it is vital to prove that the care you provided was professional and safe. • Documentation lasts forever; liability doesn’t. o Even though your documentation will become a part of your patients’ permanent medical records, you don’t have to worry about if or how that documentation could come back to haunt you forever, at least from a legal point of view. The statute of limitations for most medical malpractice cases is two to four years. This means that, no matter what happened to a patient you cared for (or how shoddy your documentation of those events may be), a patient and his or her lawyer would have a very difficult time holding you or other healthcare professionals liable for any oversights or wrongdoing after that time. Hopefully you’ll never face a lawsuit or sanction on your license, but this is important information to possess nonetheless. TBPI – 07/10/2020 5 Format of Notes • Use SOAP format: o Subjective, Objective, Assessment, and Plan (SOAP) note documentation format is the most common method of clinical notetaking. o Subjective: Received from the patient, the initial subjective portion includes history of illnesses, surgical history, current medications and allergies. Use direct patient quotes to demonstrate your attention to patients, highlight main areas of concern, build credibility into the record and accurately document a patient's competency, affect and attitude. Not unexpectedly, a patient's self-portrayal may markedly change between the time of your encounter and the time of an appearance before an attorney or jury. For example, if during an initial visit a patient says, “I've been to 20 doctors, and no one can help me,” documenting such a remark communicates his or her attitude. Patients' abusive or threatening words will sufficiently demonstrate their level of cooperation and credibility, while removing any biases in your interpretations. Complete the review of systems with an inquiry such as, “Do you have any other concerns?” Documenting all concerns addressed demonstrates your thoroughness in obtaining the patient's history and avoids later charges that the patient brought an important symptom to your attention that you ignored or neglected. o Objective: the objective portion should include vital signs and measurements, abnormalities in any, and results of physical examinations and previous laboratory and diagnostic tests. This is where the measurable, reproducible data should be included. Include supportive, reproducible observations. If a child appears “nontoxic,” list the reasons that justify this description, such as “Child climbing on exam table” or “Child irritable but consolable within 10 seconds.” Document the accuracy of specific measures. For example, record serial weights on a dehydrated infant with “12-ounce weight loss, same scales.” If you don't take them yourself, confirm vital signs and note that you've done so. Normal adult respiratory rates are 12 to 16 breaths per minute, but the TBPI – 07/10/2020 6 seemingly universal 20 breaths per minute listed on nursing charts and “neglected” by you on a progress note may represent overlooked respiratory distress to a reviewer. Because patients sometimes present with apparently abnormal vital signs that correct during their visit, when appropriate, recheck their vital signs at the end of the visit and document corrected measures. Perform sensitive examinations, such as breast or genital exams, with a qualified assistant present. Credit your caution and sensitivity by beginning your documentation with “Chaperoned exam of … ” and “Exam assisted by … .” Include the assistant's initials to confirm who witnessed your care. Careful documentation in this area is especially important because allegations of improper touching are criminal charges not covered under medical malpractice insurance policies. Avoid judgmental or potentially anger-provoking descriptors. If commenting on a patient's hygiene is necessary, replace pejorative entries such as “Needs a bath” with factual statements such as “Hair oily. Scent of body sweat present.” Include descriptions of non-medical findings that lend insight, but exclude your interpretation of their broader meanings. For example, use “Two-inch black swastika tattoo present on left biceps.” Leave it to reviewers to draw their own conclusions as to the meaning of such findings. Avoid embarrassing or easily misunderstood descriptors. SOB may accurately apply to a patient. However, the patient may respond to such a label with anger. Remember, the medical record belongs to the patient. It's easier to avoid using potentially confusing descriptors than to disabuse patients of solidified misunderstandings later. o Assessment: includes the diagnosis of the patient’s condition based on the medical history and objective data. Discuss the differential diagnosis and provide a reasoning for why you have reached the diagnosis you have. This is the section wherein you should include your opinion. Your documentation in this section should preclude absolutism and provide an impressive record of your comprehensive care. Avoid false certainties in diagnoses and reduce the burden of unmet expectations by accurately aligning patient hopes with likely outcomes, and document that you've done so. For TBPI – 07/10/2020 7 example, the statement “likely gastroenteritis, appendicitis possible” preserves your open-minded approach during an initial visit with the parents of a child experiencing abdominal pain. To patients, their families and jurors, unmet expectations are the emotional equivalent of broken promises. Disappointment provokes anger. Anger precipitates malpractice claims. Understand that while patients may desire and appreciate immediate and firm diagnoses for their ailments, a diagnosis cannot always be given with certainty. Many people with diseases lack the “classic” features of their specific disease, and many people unfettered by a specific disease may have “classic” findings. Physical examinations, laboratory evaluations and imaging studies are better at ruling diagnoses out than ruling them in. Because of this and the revealing effects of time on treatment response, view diagnoses as works in progress and document accordingly. Clearly explain to your patient that the assessment is an opinion, new findings may develop, different explanations may be found and additional treatments may be necessary. Document that you've talked about this. o Plan: What will you do to treat the patient’s concerns and goal of the therapy? This section includes lab orders, radiological work, referrals, procedures performed, medications given, and education provided. It will also include a note of what was discussed or advised as well as timings for further patient review or follow-up. Think of this section as the “options” section of the chart. • Throughout the care process, discuss the alternatives, risks and benefits of evaluations and treatments, including a review of likely outcomes if a treatment or medication is withheld or refused, and document the discussion. You will also include any advice you provide to the patient in this section. • Eliminate festering misunderstandings by confronting unreasonable expectations. For example, you could document “Futility of antibiotics in this situation reviewed” in a case in which you did not write a prescription that a patient thought was necessary for treatment. This approach may also prevent an adverse TBPI – 07/10/2020 8 response to an inappropriate treatment and uncover a patient-physician relationship in need of attention. Open disagreement need not damage the patient-physician relationship, but neglected discontent spoils the engagement necessary to achieve successful outcomes. • Document your encouragement of health maintenance and wellness. “Urged smoking cessation and offered assistance” or “Encouraged safety-belt use” are types of incidental advice we repeatedly include in patient encounters, but sometimes forget to add to our notes. Credit your thoroughness and avoid allegations of “You never told me … .” • Protect people who are not your patients through proxy advice. “Advised to notify sexual contacts,” “Advised that household contacts need prophylaxis” or “Contagious nature of conjunctivitis reviewed” are a few examples that apply. Don’t forget to include your plan: • Document goals or expected outcomes and specify a time frame for reaching them. Include interval instructions in case of changes in the patient's condition. For example, “Recheck if not better in five days, sooner if worse.” • Complement a concise statement of the agreed plan with a statement such as “Patient understands and agrees,” which seals the patient's accepted responsibility into his medical record. • Anticipate possible serious adverse outcomes, teach your patients to notify you if they occur and document that you've done so. Inform patients of your practice's 24hour, 365-day access policy, and advertise it in your notes. “Patient knows to call any time if an emergency arises” reminds reviewers of the tremendous efforts you expend on the patient's behalf. • When medications (including alternative therapies) are prescribed, review their known common and severe side effects. Encapsulate lengthy medication risk reviews in the notation by stating “… with warnings.” For example, “Prescribed lisinopril 10 mg with warnings, #30, 5 refills.” TBPI – 07/10/2020 9 • Without necessarily discouraging their use, address patient-prescribed treatments with “Communicated that risks and benefits of self-selected treatments not wholly known.” • Document follow-up arrangements with “Patient agrees to follow up” or “Patient states he'll keep appointment.” If a patient breaches an agree-appointment, boldly note this and your progressive attempts to re-establish patient care. TBPI – 07/10/2020 10 Good Note Writing • Do’s and Don’ts of good note writing: o Be concise, tell a story but avoid extraneous details that do not add to the narrative your note should convey. For example, include the severity of a car accident that lead to the patient’s presentation to our office, you may even include details of injuries sustained by other passengers in the vehicle, but the fact they were driving home after eating a pepperoni pizza would be irrelevant. o Include adequate details. Do not exclude information critical to explaining treatment decisions. Describe the symptoms the patient is reporting and the signs you see—or do not see. Describe the events leading up to the current patient visit in chronological order as much as possible. • For example, past medical history should precede the current medical complaints. (i.e. “Patient suffered injuries from an oil rig explosion and also has multiple sclerosis.” While both may be relevant to the patient’s presentation to the provider, they should be separated in the narrative so that the reader of the note understands the patient is presenting for the acute injuries from the accident. Such as “Patient has a history of multiple sclerosis. Patient presents to our office to today with complaints of pain arising from injuries sustained in an oil rig accident on June 12, 2020.”) o When evaluating and describing the patient’s pain your notes must contain clear, well-reasoned explanations. As much as possible, ask and record the patient’s exact response. Patient says “I hurt in the morning” should be replaced with: Patient says “when I get up in the morning, I can hardly move until after I have taken some pain medications.” Continue to ask further questions until you have a complete picture of patient’s complaints. If the patient simply says “I am in pain” continue to ask them to describe the pain until you have all the details. o Remember that other clinicians will view the chart to make decisions about your patient’s care. Especially in the pain management field, your work may be read and critiqued by primary care physicians, worker’s compensation case workers, and attorneys, as well as the other TBPI – 07/10/2020 11 • • • • • • providers in the practice. Your notes much be self-explanatory and not leave out important details. If you feel that you would need to say something else to Dr. Singer when he reads the note in order to explain your thought process, include that information in the note. o Write legibly. Illegible or illogical notes are not a defense against legal action. Incomplete and inconsistent notes annoy and frustrate the people who cannot understand them and inspire a lack of trust and confidence in the doctor who wrote them. (And they are not likely to fool a jury.) Your progress note may be your best—and only—defense against a malpractice claim. Your progress note must include everything you saw/did for the patient. If you do not chart it – you did not think it, or do it. The note must be selfcontained and fully explanatory. The medical record should never be erased or altered. o Never add any details that the patient has not provided to you. If necessary add the patient’s statement in quotes. o Do not embellish the narrative. Detail is important, but you are not writing a novel. (No one wants to see “it was a dark and stormy night” in the note unless it is directly relevant to the diagnosis or care of the patient.) Take care when describing the patient’s physique or attitude. While descriptions of both can be relevant to the care provided to the patient, remember the patient has the right to read and review their note at any time. Do not use derogatory language to describe a patient. For example “fat” should be replaced with “overweight” and “nasty and rude” should be replaced with “patient uncooperative.” Notes from various specialties, including nursing records, should be documented in the patient chart. If any of these include discussions held outside of normal working hours, those entry notes should clearly state the time and location of the discussions and state that the entry is made retrospectively. Remember the clinical content of a progress note should state in full a legible and understandable history. This should include a full assessment, including the positive and negative findings, interventions, and outcomes, as well as initial and ongoing assessments by each provider. Legible instructions should be included for all treatment therapies and medications. These records should be factual, consistent, and accurate. TBPI – 07/10/2020 12 • Peer-review processes should be noted; however, do not indicate in the chart that an incident report has been filed or an event report has been completed. This can serve as a red flag and could give the plaintiff’s attorney the right to access the record. TBPI – 07/10/2020 13