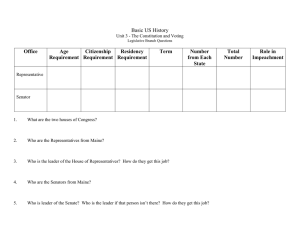

Objective: Students will be able to describe the structure of Congress and list the qualifications for congressional membership.. Do Now: Answer the questions based on the image below. Share your answer with a partner. Content Vocabulary bicameral legislature A two-chamber legislature session A period of time during which a legislature meets to conduct business census A population count reapportionment The process of reassigning representation based on population after every census redistrict To set up new district lines after reapportionment is complete gerrymander To draw a district’s boundaries to gain an advantage in elections at-large As a whole; for example, statewide censure A vote of formal disapproval of a member’s actions incumbent Candidate who is already in office Mini – Lesson: Close Reading – Congressional Membership The United States Congress is a bicameral legislature. It is made up of two houses, the Senate and the House of Representatives. Today Congress plays an important role in policy making by passing laws dealing with everything from health care to tax changes. Congressional Sessions Each term of Congress is divided into two sessions, or meetings. A session lasts one year and includes breaks for holidays and vacations. Congress remains in session until its members vote to adjourn. If Congress is adjourned, the president may call it back for a special session. 1. How long does a term of Congress last? Membership of the House The House of Representatives has 435 members. House seats are apportioned, or divided, among the states based on population. Each state has at least one seat, no matter how small its population. Qualifications The Constitution states that a representative must be at least 25 years of age, a citizen of the United States for at least seven years, and a legal resident of the state that elects him or her. Traditionally, a representative also lives in the district he or she represents. Term of Office Members of the House of Representatives are elected for two-year terms. Elections are held in November of even-numbered years—for example, 1998, 2000, and 2002. Representatives begin their term of office on January 3 following the November election. Representatives have to run for office every two years, but the House has continuity because 90 percent of all representatives are reelected. Representation and Reapportionment The Census Bureau takes a national census, or population count, every 10 years. The population count of each state determines how many of the 435 seats in the House each state gets—a process called reapportionment. Congressional Redistricting State legislatures set up districts to elect representatives. The process of drawing new district lines after reapportionment is called redistricting. In 2006, the Supreme Court decided a case that allows legislators to redraw districts in the middle of a decade rather than only after a census. This would likely occur only if one party dominated the legislature and governorship. State legislatures have sometimes abused the redistricting power by: A. creating congressional districts of very unequal populations, and B. gerrymandering—the dominant party in the legislature draws boundaries to gain an electoral advantage. They can try packing a district: drawing lines to include as many voters as possible in one district. Remaining districts will then be safe for their party. They can also try cracking: spreading opposition voters across districts to make it more likely majority party candidates will be elected. 2. How does the census affect members of the House of Representatives? Membership of the Senate The Senate consists of 100 members—2 from each of the 50 states. Qualifications The Constitution requires a senator to be at least 30 years old, a citizen of the United States for at least 9 years before the election, and a legal resident of the state he or she represents. All voters of each state elect senators at-large, or statewide, rather than by districts. Term of Office Elections for the Senate are held in November of even-numbered years, and senators begin their terms on January 3. The terms last six years, with one-third of the senators running for reelection every two years. Salary and Benefits The Senate and House set their own salaries. However, the Twenty-seventh Amendment specifies that any new congressional salary increase takes effect after the next election. Members of Congress also enjoy benefits such as free postage for official business, a medical clinic, and a gymnasium, as well as large allowances and annual retirement pensions. Privileges of Members The Constitution states that members of Congress are free from arrest “in all cases except treason, felony, and breach of the peace” when attending Congress or on their way to or from Congress. They cannot be sued for anything they say on the House or Senate floor. Each house may expel a member for a serious offense, such as treason or accepting bribes, and may censure members who are guilty of lesser crimes. Censure is a vote of formal disapproval. 3. When are members of Congress free from arrest? The Members of Congress Congress includes 535 representatives and senators. It also includes 4 delegates in the House—one each from the District of Columbia, Guam, American Samoa, and the Virgin Islands—and one resident commissioner from Puerto Rico. None of these five can vote, but they attend sessions, introduce bills, speak in debates, and vote in committees. Nearly half the members of Congress are lawyers. A large number come from business, banking, and education. Members of Congress are typically middle-aged white males. However, Congress is beginning to reflect the diversity of the general population. For example, one recent Congress included 51 women. In Congress, a large percentage of incumbents—those already in office—win reelection. Why? They find it easier to raise campaign funds. Often districts have been gerrymandered to favor the incumbents’ party. In addition, incumbents are well known to the voters and use their power to solve voters’ problems. Candidates running for Congress have begun using the Internet as a campaign tool. Nearly all candidates now have election websites that are used as electronic brochures, as voter recruitment tools, to raise campaign contributions, or to broadcast speeches. Some experts predict that candidates will make greater use of Web technologies in the future, to identify important issues, target voters, and improve communication within campaign organizations. 4. Describe a typical member of Congress. Medial Summary: Answer the following questions using but, because or so. 5. How can you compare the contrast the qualifications for senators and representatives? Activity: Working with a partner, read and annotate the paragraphs below. Then answer the questions that follow. Summary / Evaluation: Give a brief summary of article (main idea and key points. Review the answers to the questions Homework: Complete Section Quiz 5-1; Go to your school email and search for the email from the organization called the hirecause.com; register on the site. Prompts 1 and 2 are due next week Monday to be graded. Constitutional Connections: Sexual misconduct, abuse of power and congressional self-governance By JOHN GREABE, Sunday, November 26, 2017, www.concordmonitor.com Over the past year, a number of prominent politicians have been publicly accused of serious sexual misconduct and abuse of power. The question therefore has arisen: Can these politicians either be barred from taking office or removed from office on the basis of these accusations? Such charges have recently been made against Roy Moore (republican), Al Franken(democrat) and John Conyers (democrat). All three have been accused of sexual misconduct and, in Moore’s case, sexual assault against a child. Conyers also has been accused of misusing congressional funds to settle sexual harassment claims. 1. What is the problem that some politicians are facing? So what if anything can Congress do? Let’s start with the relevant provisions of the Constitution’s text. Article one, section five, clause one states: “Each House (of Congress) shall be the Judge of the … Qualifications of its own Members.” And article one, section five, clause two provides: “Each House may determine the Rules of its Proceedings, punish its members for disorderly Behaviour, and, with the Concurrence of two-thirds, expel a Member.” 2. According to the text, which branch of the government has the responsibility of dealing with the alleged wrongdoing of the Congressmen? What does the constitution specifically say? The first of these provisions might seem to invite the Senate to reject Moore as “unqualified,” should he be elected. But Powell v. McCormack, a 1969 Supreme Court decision that stands as one of the few cases imposing constitutional limits on congressional self-governance, does not permit this interpretation of the Constitution’s meaning. The case involved Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who in 1966 was elected to represent New York’s 18th congressional district in the 90th Congress. During the 89th Congress, a House special subcommittee investigated the expenditures of a committee that Powell then chaired and concluded that Powell and certain committee staff had deceived House authorities about their travel expenses. The subcommittee also found strong evidence that Powell had directed his committee to make illegal salary payments to his wife. But no action was taken against Powell during the 89th Congress. When the 90th Congress met to organize in January 1967, House leaders barred Powell from taking the oath of office. The House then voted to exclude Powell as “unqualified” and notified the governor of New York that Powell’s former seat was vacant. 3. According to the text, what exactly was Powell accused of doing? What actions were taken by Congress to deal with his behavior? Powell and several of his constituents sued House Speaker John McCormack and other House leaders, and the case went to the Supreme Court. The defendant House leaders argued, among other things, that the Constitution assigned to Congress sole responsibility for judging the qualifications of its members, and that the court should treat the issue as a “political question” not suitable for judicial resolution. But the Court disagreed. Relying on records of debates during the Constitutional Convention, commentary from the ratification period, and early congressional applications of its article one, section five powers, the court held that Congress may exclude a member-elect as “unqualified” only if it concludes that the member does not meet one of the standing qualifications specified in the Constitution: age (25 for the House; 30 for the Senate); citizenship (for seven years for the House; for nine years for the Senate); and that the member-elect be an inhabitant of the represented state. Expulsion is a different matter. As noted above, the Constitution expressly contemplates “punishment” for “disorderly Behaviour.” But it says nothing about the grounds for expulsion. Thus, if we are to be guided only by the Constitution’s text, Congress’s power to expel would seem to be unlimited. 4. What arguments did the members of Congress give to the Supreme Court to justify their actions? 5. Who did the Supreme Court rule in favor of? 6. How can a member of Congress become disqualified? 7. How can a member of Congress be expelled from Congress? Historically, however, Congress has exercised the expulsion power infrequently. There have been only 20 congressional expulsions, and most were for disloyalty during the Civil War. Because expulsion runs the risk of being seen as overriding the will of the voters, many members of Congress have expressed the view that expulsion should be based only on behavior that occurs after a member’s most recent election. But this view is not universally shared, and many others have opined that expulsion could be appropriate in circumstances where the misconduct was unknown to the voters at the time of election. That said, most agree that expulsion of a member for conduct that was known to the voters at the time of election would raise serious concerns. Such an expulsion would be seen by many as inconsistent with the idea that sovereignty in our system lies with “We the People,” and not those elected to represent us. (John Greabe teaches constitutional law and related subjects at the University of New Hampshire School of Law. He also serves on the board of trustees of the New Hampshire Institute for Civics Education.) 8. Why should members of Congress be careful how they use this power? 9. Based on the information in the text, what action can Congress take against Roy Moore who at the time of this article running for re-election? 10. Based on the information in the text, what action could Congress take against Al Franken and John Conyers who were currently in Congress at the time of the writing of this article?