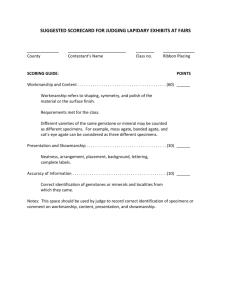

Workmanship From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to navigation Jump to search Rolls Royce are so renowned for their workmanship that the name is used for any work of the highest quality. Workmanship is a human attribute relating to knowledge and skill at performing a task. Workmanship is also a quality imparted to a product. The type of work may include the creation of handcrafts, art, writing, machinery and other products. Contents 1 Workmanship and craftsmanship 2 Workmanship in society 2.1 Electronics manufacturing 3 Workmanship and aversion to labor 4 See also 5 References 6 Further reading 7 External links Workmanship and craftsmanship Ruben's 1536 rendition of Vulcan, the Roman counterpart of Hephaestus, the Greek God of Craftsmen. Workmanship and Craftsmanship are sometimes considered synonyms, but many draw a distinction between the two terms, or at least consider craftsmanship to mean "workmanship of the better sort".[1] Among those who do consider workmanship and craftsmanship to be different, the word "workmanlike" is sometimes even used as a pejorative, to suggest for example that while an author might understand the basics of their craft, they lack flair. David Pye has written that no one can definitively state where workmanship ends and craftsmanship begins.[1] Sing clear-voiced Muse, of Hephaestus famed for skill. With bright-eyed Athena he taught me glorious crafts throughout the world - men who before used to dwell in caves in the mountains like wild beasts. But now that they have learned craftsmanship through Hephaestus famous for his art they live a peaceful life in own houses the whole year round. - an extract from a Homeric hymn celebrating craftsmanship.[2] During the Middle Ages, smiths and especially armor smiths developed unique symbols of workmanship[3] to distinguish the quality of their work. These became some of the most unusual signs of workmanship, comparable to the mon family crests of Japan.[4] Workmanship in society Workmanship is considered to have been a valued human attribute even in prehistoric times. In the opinion of the economist and sociologist Thorstein Veblen, the sense of workmanship is probably the single most important attribute governing the material well being of a people, with only the parental instinct coming a close second.[5] There have however been periods in history where workmanship was looked down on; for example in Classical Greece and Ancient Rome, where it had become associated with slavery. This was not always the case - back in the archaic period, Greeks had valued workmanship, celebrating it in Homeric hymns.[6] In the western world, a return to a more positive attitude towards work emerged with the rise of Christianity.[7] In Europe, Veblen considers that the social value of workmanship reached its peak with the "Era of handicraft". The era began as workmanship flourished with the relative peace and security of property rights that Europe had achieved by the Late middle ages. The era ended as machine driven processes began to displace the need for workmanship after the Industrial revolution. Workmanship was such a central concept during the handicraft era, that according to Veblen, even key theological questions about God's intentions for humanity were re-framed from "What has God ordained?" to "What has God wrought?".[8] The high value placed on workmanship could sometimes be an oppressive force for certain individuals - for example, one explanation for the origin of the English phrase sent to Coventry is that it was born from the practice where London guild members expelled due to poor workmanship were forced to move to Coventry, which used to be a guild free town. But workmanship was still widely appreciated by the common people themselves.[8] For example, when workers accustomed to practicing high standards of workmanship were first recruited to work on production lines in factories, it would be common for them to walk out, as the new roles were relatively monotonous, giving them little scope to use their skills. After Henry Ford introduced the first Assembly line in 1913, he could need to recruit about ten men to find one willing to stay in the job. Over time, and with Ford offering high rates of pay, the aversion of labor to the new ways of working was reduced.[9] Workmanship began to receive considerable attention from scholars once its place in society came under threat by the rise of industrialization. The Arts and Crafts movement arose in the late 19th and early 20th century, as workmanship began to be displaced by developments like greater emphases on process, machine work, and the separation of design and planning skills from the actual execution of work. Scholars involved in founding the movement, like William Morris, John Ruskin and Charles Eliot Norton, argued that the opportunity to engage in workmanship used to be a great source of fulfillment for the working class.[8] From a historical perspective however, the arts and crafts movement has been seen as a palliative, which unintentionally reduced resistance to the displacement of workmanship.[9][10] In a book written on the nature of workmanship, David Pye writes that the displacement of workmanship has continued into the late 20th century. He writes that since World War II especially, there has been "an enormous intensification of interest in design", at the expense of workmanship. The trend started in the 19th century has continued, with Industrial processes increasingly designed to minimize the skill needed for workers to produce quality products.[11] 21st century scholars such as Matthew Crawford have argued that office and other white collar work is now being displaced by similar technological developments to the ones that caused large numbers of manual workers to be made redundant from the late 19th to early 20th century. Even when the jobs remain, the cognitive aspects of the jobs taken away from the workers, due to knowledge being centralized. He calls for a revaluing of workmanship, saying that certain manual roles like mechanics, plumbers and carpenters have been resistant to further automation, and are among the most likely to continue offering the worker the chance for independent thought.[9] Writers like Alain de Botton and Jane McGonigal have argued that the world of work needs to be reformed to make it more fulfilling and less stressful. In particular, workers need to be able to make a deeply felt imaginative connection between their own efforts and the end product. McGonigal argues that computer games can be a source of ideas for doing this; she says the primary reason for World of Warcraft being so popular is the sense of "blissful productivity" that its players enjoy.[12][13] Electronics manufacturing The reliability of electronic devices is greatly affected by the quality of the workmanship. Therefore, the electronics manufacturing industry has developed several voluntary consensus standards to provide guidance on how products should be designed, built, inspected, and tested.[14] Workmanship and aversion to labor It has often been held in older economic writings that people are always adverse to labor and can only be motivated to work by threats or tangible rewards such as money. While Christianity has generally been positive about workmanship, certain Bible passages such as Genesis 3:17 ("...Cursed is the ground because of you; through painful toil you will eat food from it all the days of your life.") have contributed to the view that labor is a necessary evil, part of the punishment for original sin,[7] but work existed before original sin and the fall of man in Genesis 2:15 ("Yahweh God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to work it and keep it.") The view that work is a punishment takes Genesis 3:17 out of context. God's curse wasn't work, but that work would inherently be harder. Veblen and others agree with this view, saying that work can be inherently joyful and satisfying in its own right. Veblen acknowledges that humans have an innate tendency towards idleness, but asserts that they also have a countervailing tendency to value work for its own sake, as is demonstrated by the vast amount of work that is undertaken without obvious external pressure. As evidence for the widely shared instinct towards workmanship, Veblen also notes the near universal tendency for humans to approve of others' good work. Psychologist Pernille Rasmussen has written that the tendency to value work can become so strong that it stops being a positive source of motivation, contributing instead to some people losing balance and becoming workaholics.[15] [7] [10] See also software craftsmanship References Notes Citations Pye 1968, Chpt 2: The workmanship of risk and the workmanship of certainty quoted in Sennett (2009) p. 21 Ffoulkes, John. The Armourer and His Craft: From the XIth to the XVIth Century. Dover, 1988. Matsuya Piece-Goods Store. Japanese Design Motifs: 4,260 Illustrations of Japanese Crests. Dover, 1972. Veblen 1914, Chpt 1: Introduction Sennett 209, pp. 22-23 Rasmussen 2008, Chpt 2: Work Curse or Blessing Veblen 1914, Chpt 6: The era of handicraft Matthew B. Crawford (Summer 2006). "Shop Class as Soulcraft (for a fuller treatment, see the authors 2011 book of the same name)". The New Atlantis. Retrieved 2013-06-13. Jackson Lear 1994, Chpt 2: The figure of the artisan: arts and crafts ideology Pye 1968, Chpt 1: Design proposes: Workmanship disposes de Botton 2010 McGonigal 2011, Chpt 3: More satisfying work L-3 Communications, WS-000: Workmanship Standards Introduction Thorstein Veblen (1898). "The Instinct of Workmanship and the Irksomeness of Labor". American Journal of Sociology. 4. Retrieved 2013-08-26. Sources Veblen, Thorstein (1914), The Instinct of Workmanship and the State of the Industrial Arts, Transaction Pub, ISBN 9780887388071 Pye, David (1968), The Nature and Art of Workmanship, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521060165 Jackson Lears, T.J (1994), No Place of Grace, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 0226469700 Rasmussen, Pernille (2008), When Work Takes Control: The Psychology and Effects of Work Addiction, Karnack books, ISBN 1855755939 Sennett, Richard (2009), The Craftsman, Penguine, ISBN 9780141022093 de Botton, Alain (2010), The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, Penguin, ISBN 0141027916 McGonigal, Jane (2011), Reality is Broken, Random House, ISBN 9780099540281 Further reading Risatti, Howard (2009), "Design, Workmanship, and Craftsmanship", A Theory of Craft: Function and Aesthetic Expression, University of North Carolina Press, ISBN 9780807889077 Smith, Kate (2010), The Potter’s Skill : perceptions of workmanship in the English ceramic industries, 1760-1800 Smith, Kate (2012), "Sensing Design and Workmanship: The Haptic Skills of Shoppers in Eighteenth-Century London", Journal of Design History, 25 (1): 1–10, doi:10.1093/jdh/epr053 Van der Beek, Karine (2013), England's Eighteenth Century Demand for High-Quality Workmanship: Evidence from Apprenticeship, 1710-1770 Quiller-Couch, Arthur (2008), Shakespeare's Workmanship, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9780521736817 External links Wikiquote has quotations related to: Workmanship Authority control Edit this at Wikidata LCCN: sh85148181 Categories: Production and manufacturingQuality Navigation menu Not logged in Talk Contributions Create account Log in Article Talk Read Edit View history Search Main page Contents Current events Random article About Wikipedia Contact us Donate Contribute Help Community portal Recent changes Upload file Tools What links here Related changes Special pages Permanent link Page information Wikidata item Cite this page Languages العربية မန် ဘာသာ မမန်မာဘာသာ Portugu ês Edit links In other projects Wikiquote Print/export Download as PDF Printable version This page was last edited on 11 July 2019, at 17:05 (UTC). Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia® is a registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization. Privacy policy About Wikipedia Disclaimers Contact Wikipedia Developers Statistics Cookie statement Mobile view Wikimedia Foundation Powered by MediaWiki