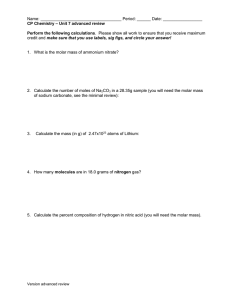

Australian Dental Journal The official journal of the Australian Dental Association Australian Dental Journal 2019; 0: 1–10 doi: 10.1111/adj.12716 The extraction of first, second or third permanent molar teeth and its effect on the dentofacial complex A Hatami, C Dreyer Department of Orthodontics, School of Dentistry, The University of Adelaide, Adelaide, South Australia, Australia. ABSTRACT The extraction of permanent molar teeth was first introduced in 1976 as a substitution for premolar extraction in cases with mild crowding. Since then, a number of studies have investigated the effect of permanent molar extraction on dentofacial harmony. Undertaking the procedure of molar extraction is most commonly recommended in response to factors such as: gross caries, large restorations and root-filled teeth, along with its application in the management of anterior open bite and reduction in crowding in facial regions. It has been indicated, however, that before undertaking the extraction of molar teeth it is important to investigate the potential influence of the procedure on other molars, with particular consideration of their eruption path. This is due to the doubt as to the effect of the exact molar teeth extraction and their consequences. In light of this, This review was undertaken to investigate and compare the effect of first, second and the third molar teeth extraction and their subsequent dentofacial complex changes. Keywords: dentofacial complex, extraction, first permanent molar, second permanent molar, third permanent molar. Abbreviations and acronyms: CAI = condylar asymmetry index; TMD = temporal mandibular disorder; TMJ = temporomandibular joint. (Accepted for publication 12 August 2019.) INTRODUCTION Tooth extraction is an important issue related to the management of the dentofacial complex and its symmetry, with the extraction rate in orthodontic patients found to be about 25–80%.1–5 The loss of permanent teeth most often occurs due to caries or for the treatment and management of periodontal disease6–9 with molar teeth playing an important role in normal occlusion.10,11 The first molar extraction in 1976 was mentioned in an article by Williams, however, the technique of extraction of permanent molar teeth as the substitution for premolar extraction was first introduced for the second molar by Richardson in 1996.12,13 Numerous studies have indicated various approaches for molar teeth extraction in recent years, however, the use of extraction is still controversial, as there are no clear indications for the use of this approach. The purpose of this article is to investigate and compare the dentofacial complex changes which © 2019 Australian Dental Association arise from the undertaking of the first, second and third molar extraction. FIRST MOLAR EXTRACTION Chronology and dimensions The movement of a tooth from its development site in alveolar bone to the occlusal plane is termed a tooth eruption.14 This path of eruption is not reliant on pressure from the tooth itself and is instead considered a genetic phenomena. The timing of the eruption of permanent teeth is specifically dependent on the loss of antecedent teeth.15–17 There are numerous factors which might affect permanent teeth eruption and their chronology such as hyperdontia, trauma and cysts, all of which are pathologic conditions affecting eruption by commanding space. Additionally, the presence of general factors could be important in eruption including genetic influences, gender, social and economic conditions, the geographic region and the consumption of fluoride.18–23 1 A Hatami and C Dreyer First evidence of calcification Enamel completed Eruption Root completed Overall length Crown length Root length Crown width Mesio-Distal Crown width Bucco-Lingual Root to crown ratio At birth 3–4 years 6 years 9–10 years Mandibular first molar (mm) 20.9 7.7 14.0 M root 13.0 D 11.4 10.2 1.83 Maxillary first molar (mm) 20.1 7.5 12.9 MB root 12.2 DB 13.7 L 10.4 11.5 1.72 were based on endodontic and restorative treatment need.45 Practitioners prefer extraction of this tooth to premolars because of its high rate of caries, root-fillings and its effect on relieving crowding.32,46 Bayram and colleagues showed that the extraction of the first molar could be useful as the space for third molar eruption is increased, the effects of which are more favourable for upper third molars in comparison with the lower.47 Disadvantages and contraindications of first molar extraction Additional studies have investigated the disadvantages of the first molar extraction26,48. These include: Advantages and indications of first molar extraction Losing the first molar for any reason can be a challenge for the developing occlusion especially in the mixed dentition stage24 as the first molar is an important tooth in the development of normal occlusion of both arches.10 It has been indicated that the first molar tooth is more often exposed to caries which can lead to early extraction of the tooth25–28, however, overall the development of caries in children and adolescents has decreased since 1980.29–31 The most common indications for the extraction of this tooth are caries, endodontic problems, and cases of hypomineralization.32 First molar extraction advantages and indications: (a) Management of impaction. It has been indicated that due to the lack of space the third molar could become impacted and that this tooth shows the highest impaction rate of all teeth. In a study carried out by Ay et al., it was suggested that mandibular third molar eruption could be facilitated by mandibular first molar extraction.33 (b) Management of molar incisor hypomineralization. This condition which is estimated to involve about 25% of European children and 3.6–19% in other populations34–38 is defined as inadequate mineralization in molar teeth34 resulting in a painful sensation when brushing or breathing cold air in which can require complex treatment.38,39 Jalevik et al. evaluated 27 children with hypomineralized teeth, and found that extraction of the first permanent molar could be beneficial. The study also found that the patient’s permanent dentition positioning and the reduction of the space did not cause particular concerns.40 Regardless of other conditions restorative treatment of hypomineralized molars caused practitioners a variety of management problems.41–44 (c) First molar extraction as part of orthodontic treatment. In 2010, Ong et al. suggested first molar extraction and its advantages and disadvantages 2 (a) Tipping of adjacent teeth towards the extraction site; (b) Shifting of the dental midline towards the site of the extraction; (c) Change in chewing habits; (d) Periodontal and temporomandibular joint problems. Of particular concern is the potential of the first molar extraction to negatively impact on dentofacial symmetry. This is defined as the similarity in shape and volume of both sides of the face, however, the exact equilibrium is theoretical.49–51 Caglaroglu and colleagues demonstrated, by using postero-anterior radiographs in 25 patients with maxillary permanent first molar extraction, 26 mandibular permanent first molar extraction and 30 controls, that patients who had early molar extraction could be faced with dental and skeletal asymmetry. This finding was also supported by Farkas and Hewitt amongst others.52,53 Halicioglu investigated bilateral mandibular first molar extraction and its effect on asymmetry in adult patients. In this study, the Condylar asymmetry index (CAI), ramal asymmetry index and condylar plus ramal asymmetry index were measured. The study found that the CAI was increased in both cases and control groups, however that there was no significant difference between the groups.54,55 By considering these studies, it can be suggested that the extraction of the first molar at mixed dentition stage could be important in dentofacial asymmetry but when this extraction happens in the adult there is no evidence of asymmetry. Furthermore, asymmetrical extractions when considered have to be evaluated carefully to prevent the side effect of asymmetry such as midline shift, temporal mandibular disorder (TMD) and cross bite. Timing for first molar extraction The differences in mandibular and maxillary first molar eruption could play an important role in © 2019 Australian Dental Association Molar extractions extraction timing.56 There are limited studies on this subject. Conway et al. in an evaluation of three cases showed that maxillary Molar extraction results were favourable in two children who were aged more than 11 years in comparison with one child at 8 years.57 Additionally, Jalvek’s study showed that the result of the maxillary first molar extraction in patients older than 8 years could be more promising in comparison with those under 8 years.40 The mandibular first molar extraction was also investigated in studies by Conway and Jalevik. In the Conway study, a mandibular first molar extraction was performed in two patients aged 11 and 12 years, however, the results of the extractions were inconclusive. However, in Jalevik’s study the mandibular extraction in 12 patients showed favourable results despite the differences in their age.40,57 Considering the limited number of studies there is not enough evidence to determine a definite conclusion, however, based on current literature, it is suggested that the extraction of the first molar is favourable in orthodontic treatment of patients older than 8 years old. Ay et al. noted that the early extraction of the first molar could cause dentofacial asymmetry, premature contacts and uncontrolled tipping.58 Other molar position changes after first molar extraction The loss of a permanent maxillary first molar is commonly followed by a mesial drift of the second (a) (b) Fig. 1 In this patient the first molar extraction effect on the third molar development is illustrated. This panoramic radiograph shows third molar development acceleration in the maxillary (a) and mandibular (b) where extraction of the first molar has occurred.61 © 2019 Australian Dental Association molar, which along with the extraction of the first molar can provide a favouable space for third molar eruption into the second molar site.47 Additionally, the extraction of the second molar might trigger this shift by better positioning the third molar at the time of its eruption.59,60 Halicioglu et al. investigated permanent first molar extraction effects on the third molar development and showed that the extraction of the first molar can have beneficial effect on developmental acceleration of the third molar on the mandibular and maxillary extracted side (Fig. 1).61 In addition, first molar extraction can also provide a greater vertical angulation of third molar (Table 1).33,47 Angle’s classification in first molar extraction Angle’s classification is a common method for the evaluation of malocclusion of teeth.62 Teo et al. investigated the Angle’s classification in patients with first molar extraction and the position of the second molar after 5 years. They could not show any significant association between Angle’s classes and space closure. Even by considering any significant relationship most of the cases with upper first molar extraction led to adequate space closure.59 SECOND MOLAR EXTRACTION A permanent second molar is the tooth located distally from the first molars and mesial from the third molars.63 The first molar tooth might be sacrificed during orthodontic extraction26 however, the special anatomical position of the second molar and the outcome of extraction modalities has been the focus of attention for some time in the Western world.63,64 Recently, second molar extraction has become a topic of interest and controversy among dental professionals.65 There is discordance in the scientific literature on the conditions of the adjacent second molar associated with the extraction of neighbouring molars. Retrospective studies have reported relatively high residual periodontal defects at the distal aspect of the second molar after third molar extraction.66–69 However, some prospective studies have shown different clinical outcomes with relative periodontal improvements.67,70,71 Studies have shown different results of improvement, unchanged or even deterioration of periodontal status.67 Orthodontic treatment involving the extraction of the second molar comparably takes significantly shorter time for periodontal ligament to heal than with non-extraction methods of treatment.72 3 A Hatami and C Dreyer Table 1. Important studies in this field and their Intended conclusion Author Year Conclusion Yavoz 2006 Ay 2006 Jalevik 2007 Caglaroglu 2008 Bayram 2009 Teo 2013 Halicioglu 2013 Halicioglu 2014 The extraction of the first permanent molar can induce third molar eruption in early ages First molar extraction increases the third molar space, aids in better development, eruption and better movement into the space. Also increase in vertically angulated third molars Extraction of first molar is an appropriate alternative in patients with hypomineralization.The permanent dentition positioning and dental development in these patients was suitable without any intervention Early unilateral first molar extraction can lead to dental and skeletal asymmetries First molar extraction increases the third molar eruption space and increases the maxillary third molar angulation more than the mandibular There was no statistically significant association between Angle’s classes and space closure Condylar asymmetry index were increased but there were no statistical significant difference in asymmetry between these groups The first molar extraction caused increased third molar eruption acceleration in both maxilla and mandible 3.1 Chronology and dimensions73–75 First evidence of calcification Enamel completed Eruption Root completed Overall length Crown length Root length Crown width MD Crown width BL Root to crown ratio Mandibular second molar (mm) 20.6 7.7 13.9 M root 13.0 D 10.8 9.9 1.82 2.5–3 years 7–8 years 11–13 years 14–15 years Maxillary second molar (mm) 20.0 7.6 12.9 MB root 12.1 DB 13.5 L 9.8 11.4 1.70 Advantages and indications of second molar extraction Second molar extraction has been recommended as an orthodontic treatment option.77 The indications for the extraction of the second molars include: (a) Presence of severe caries. (b) Ectopically erupted or severely rotated molars.76–79 (c) Existence of mild-to-moderate arch length deficiencies with concurrent good facial profiles. (d) Crowding in the tuberosity area with a need to facilitate first molar distal movement.57 (e) Relief of malocclusions developed from the eruption forces of permanent molars.80 (f) Facilitate the eruption of the third molars, thus avoiding the need for surgical extraction. Other advantages and considerations of second molar extraction include: 4 Patients number Mean age Ref 165 15.35 2.53 122 107 patients with unilateral mandibular first-molar extractions 27 25.69 33 8.2 40 25 maxillary/26 mandibular/30 control 41 18.25 49 16.6 47 63 8.9 59 30 and 25 control 18.24 1.17 54 2925 panoramic radiographs 13–20 years 61 (a) The minimal impact on the anterior profile of the face due to the lack of visiblity.73,81,82 (b) Significantly shorter time to heal compared to the non-extraction approach of orthodontic treatment.72 (c) Facilitation of treatment using removable appliances. (d) Disimpaction and faster eruption of third molars. (e) Prevention of ‘late’ incisor imbrication, fewer ‘residual’ spaces at the end of orthodontic treatment. (f) Less likelihood of relapse. (g) Favourable functional occlusion and mandibular arch formation.72,83 Disadvantages and contraindications of second molar extraction Various authors have reported some drawbacks regarding extraction of the second molar tooth, including the 84 (a) Tipping and drifting of the adjacent teeth, usually followed by missing mandibular second molars. (b) Supraeruption of unopposed teeth. (c) Poor gingival contours. (d) Poor interproximal contacts. (e) Reduced inter-radicular bone and pseudopockets.85 (f) Late lower arch crowding when extracted in the presence of a developing third molar with insufficient space.86 (g) The development of cervicofacial subcutaneous infections which might follow incomplete second molar extraction.64,87 © 2019 Australian Dental Association Molar extractions Other disadvantages of second molar removal as reported by several authors include: (a) Frequent undesirable positions of erupted third molars resulting in a second late stage of fixed appliance therapy. (b) That the extraction site is located far from the area of concern in moderate-to-severe anterior crowding.11,60,65,72,81 Timing for second molar extraction It is believed by many orthodontists that the optimum age for second molar extraction as a therapeutic method is between 12 and 14 years, with the importance of the position of the third molar is equally highlighted allowing the fill-in of space left by the second molar.80,88 The consensus of several reports is that the optimal time of extraction of the second molar is as early as it erupts, provided that the third molar crown is complete but before any reliable evidence of root formation. The axial alignment and angulation of the third molar bud plays an essential role in the extraction decision, especially if indicated at a later age.79,83,89,90 Changes in other molar position after second molar extraction It is noted that the loss of permanent molars is closely followed by drift of the neighbouring teeth.91 This shift also could be triggered by the extraction of the second molar which might provide the third molar a better position and hasten the time of the eruption.59,60 In relation to the drift following extraction, Wieslander reported that the third molars usually assume a downward and forward orientation,80 with Richardson et al reporting slight distal movement of the first molars and a decrease in crowding.88 It is a common belief among dental professionals that in the long-term perspective, unopposed molars tend to over erupt following the extraction of the molars. Livas et al found insignificant changes in the eruptive movement of unopposed mandibular second molars.92 However, according to Breakspear: (a) Path of eruption of the third molar could be affected by the over eruption of the opposing second molar. (b) Distal migration of the first molar when there is missing second molar and premolar crowding could also effect path of eruption of the third molar. (c) Following the second molar extraction a residual space is created which is usually spontaneously closed by distal movement of the first molars and to some extent by spontaneous migration of the third molars.63,80,83,93 © 2019 Australian Dental Association A comparative study by Staggers et al., demonstrated that the maxillary and mandibular first molars were protracted a greater amount in the second molar compared to pre-molar extraction group. There appeared no change in facial profile after extraction of second-molars.83 In another study, the maxillary first molars were found to have moved distally an average of 1.2 mm following the maxillary second molar extraction.72,80,94,95 THIRD MOLAR EXTRACTION The third molar tooth (M3) is the last to appear and is the most variable tooth affected by morphology, eruption period and oligodontia/hypodontia.96 The M3 is of interest to scientists when estimating the chronological age of youngsters, to assess development, to select treatment, to establish diagnosis and to resolve legal issues and immigration.97 Wisdom teeth are the most likely to undergo impaction (incomplete eruption in the presence of a fully grown root), which occurs when there is inadequate space in the mouth, if there is an impediment by another tooth or if the tooth has developed in an abnormal position. The impacted tooth is generally trouble free and covered totally or partially by soft tissue, bone or a combination of the two.98 The development of the M3 is not without risks, however, with Mortazavi et al.99 finding with their systematic review an association between an impacted third molar and 10 different types of cysts and tumours. Chronology and dimensions The chronology of M3 varies widely across races but generally it is found that females experience M3 development earlier than their male counterpart. The earliest chronology of human dentition by Schour and Massler, that is modified from Kronfeld’s table, provides an estimate of M3 chronology with maxillary dentition in the lead. The M3 is similar to second molar being heartshaped but has a smaller crown and shorter root compared to the second molar tooth.100 First evidence of calcification Enamel completed Eruption Root completed Overall length Crown length Root length Crown width MD Crown width BL Root to crown ratio Mandibular third molar (mm) 18.2 7.5 11.8 M root 10.8 D 11.3 10.1 1.57 7–9 years 12–16 years 17–21 years 18–25 years Maxillary third molar (mm) 17.5 7.2 10.8 MB root 10.1 DB 11.2 L 9.2 10.4 1.49 5 A Hatami and C Dreyer The development and eruption of the third molar is enigmatic in orthodontics, especially the mandibular third molar.101 It’s been indicated that the early eruption of the M3 is associated with the angulation of the developing third molar, mandibular growth and the extraction of other teeth in the erupting area.101,102 The eruption of M3, like other permanent teeth, is dependent on a number of factors, including: (a) Genetic diseases such as Amelogenesis Imperfecta, Down syndrome, Neurofibromatosis etc. (b) Gender. (c) Socioeconomic status (conflicting data on higher vs. lower socioeconomic status).103 (d) Nutrition (malnutrition extending into early adulthood delayed dental eruption). (e) Systemic diseases (renal failure, anaemia and vitamin D-resistant rickets104). Advantages and indications of third molar extraction Despite its common use, the surgical removal, and the timing of the surgical removal, of asymptomatic M3 as prophylaxis to prevent related health complications is a controversial topic among health practitioners as well as public and health insurance companies103,105. As concluded by Costa et al. in their systematic review the notion of M3 extraction as a prophylaxis is null and void due to lack of sufficient evidence.106 However, a number of benefits exist for M3 extraction and studies have unanimously pointed to an earlier age of extraction to correlate favourably with lesser morbidity.107 The circumstances remaining in which extraction of the M3 is indicated, include: (a) Impaction associated with dental caries (intractable carious lesion). (b) Periodontal defects close to the preceding molar.108 (c) Pericoronitis. (d) Odontogenic cyst.109 (e) Dental tumours.105 (f) Prophylactic removal of impacted M3 is also indicated for root resorption, crowding of lower incisors and damage to the adjacent tooth.98 The M3 also plays a role as a method for evaluating a young adult age. Chronological evidence from all other bony tissues has been completed by the mid-adolescence, with the M3 having the benefit of its phase of crown-root mineralization able to be easily surveyed in a non-invasive manner from a dental radiograph. This technique is also useful in determining age in forensic science96 as well as in the evaluation of dental age to provide a vital way of monitoring whether adolescents are developing sequentially.97 Dental surgeons use an appraisal of M3 mineralization to plan autologous transplant in replacing undesirable first or second molars.109 Disadvantages of third molar extraction A number of changes post third molar extraction have been observed. (a) Increase in probing depth on the distobuccal aspect of the second molars and a reduction in attachment level after surgical removal of impacted mandibular third molar.110 (b) No appreciable gain in alveolar bone height after removal of the impacted M3 of second molars with distal bone loss due to M3 impaction.111 The extraction of M3 is a topic of ongoing controversy.112 One of ten patients after surgical removal experience associated complications that include; intense pain, swelling, haemorrhage, infection, alveolar osteitis, haematoma, lockjaw105, alveolar nerve injury113, oroantral communication, incomplete root removal, delayed healing, infected subperiosteal hematoma and bony spicule.114 Although rare, 5 in 1000 patients over 25 years of age experience mandibular angle fracture after M3 extraction.108 Patients commonly experience anxiety with the removal of M3, which has a significant impact on the outcome of the surgery due to the disturbed emotional state of the patient.115 Kim and colleagues have Table 2. Indications, disadvantages and proposed timing for extraction of molar teeth Tooth/condition Indications Disadvantages Changes in other molar position 6 First molar Second molar Third molar Caries, endodontic problems, hypomineralization Shifting of the dental midline, change in chewing habits, periodontal problems, temporomandibular joint problems Help in mandibular third molar eruption Caries, ectopically eruption, severely rotated, orthodontic treatment Drifting of the adjacent teeth, supraeruption of unopposed teeth, poor gingival contours, poor interproximal contacts, reduced inter-radicular bone, pseudopockets Caries, periodontal defects, pericoronitis, odontogenic cyst, dental tumours One of 10 patients faced with intense pain, swelling, haemorrhage, alveolar osteitis, haematoma, lockjaw, alveolar nerve injury Relieve malocclusions, facilitate eruption of the third molars, faster eruption of third molars, maxillary first molars could have move distally Relieve crowding of lower incisors © 2019 Australian Dental Association Molar extractions demonstrated a significant reduction in intraoperative anxiety of the patients in presence of their music of choice.116 Patients appreciated having a separate consultation prior to surgical visit for M3 extraction but it has no corralation to overal anxiety outcome.117 Timing for a third molar extraction There is a paucity of literature on the timing for the M3 extraction. In general, dental professionals agree that third molars should be removed whenever there is evidence that predicts: (a) Cavities that cannot be restored (b) Severe periodontal disease (c) Infections (d) Tumours (e) Cysts, and/or (f) Damage to neighbouring teeth. In terms of tooth survival to extraction among wisdom teeth in the maxillary or mandibular arch, the difference is insignificant but upper M3 survival time to extraction carries the least prognosis.118 The prophylactic M3 extraction at younger age has a more positive prognosis.107 Changes in other molar position after third molar extraction In patients with second molar extraction, usually the lower third molar erupts in an acceptable position.86 Richardson et al. recommended that the presence of the third molar could be a cause of crowding in lower arch during the post-adolescent period.119 However, there is no conclusive evidence to show the role of M3 on anterior teeth crowding. Previous studies have pointed out that molar distalization and rotation is unaffected by wisdom teeth eruption. After second molar extraction, M3 usually assumes a downward and forward orientation.80 Bayram and co-workers stated that prophylactic extraction of the first molar provides adequate space for M3 eruption and results in better angulation of maxillary M3 compared to the mandibular. This also decreases the chance of impaction of M3s.120 In another study, it was concluded that first molar extraction helps M3 occupy an optimal position but suggested if the extraction was carried out too early, this could lead to uncontrolled tipping of neighbouring teeth into the extraction space.121,122 CONCLUSION This study was carried out to evaluate dentofacial complex changes in first, second and third molar teeth extraction. A number of studies were included as part © 2019 Australian Dental Association of this review, most of which indicate that undertaking the extraction of the first, second and third molars must involve a number of considerations. These considerations include and are not limited to; (a) management of impaction (b) molar pathologies such as gross caries, dentigerous cyst etc (c) severe hypomineralization (d) age of patient (e) asymmetry and malocclusion (f) molar teeth crowding (g) Periodontal and TMJ problems There are some circumstances in which the indications for molar extraction are clear, such as when there is the presence of caries affecting the teeth. However, the studies regarding timing of planned extractions are limited and conclusions drawn require further investigation. When planning for extractions the known disadvantages do need to be considered, such as alvelolar nerve injury, intense pain, swelling and infection, unfavourable shifting of adjacent teeth, change in occlusion, TMJ problems. When extraction is planned for first, second or third molars, the patients’ age and the optimum timing for the extraction needs to be carefully considered. This study suggests that the approach to dental molar extraction must include the careful consideration of the effects of the extracted molar on other molars, the faciodental complex and its symmetry (Table 2). CONFLICTS OF INTEREST The authors disclose no conflicts of interest. This research has not received any funding. All authors have viewed and agreed to the submission. REFERENCES 1. Proffit WR. Forty-year review of extraction frequencies at a university orthodontic clinic. Angle Orthod 1994;64:407–414. 2. Janson G, Maria FRT, Bombonatti R. Frequency evaluation of different extraction protocols in orthodontic treatment during 35 years. Prog Orthod 2014;15:51. 3. O’Connor BM. Contemporary trends in orthodontic practice: a national survey. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1993;103:163–170. 4. Peck S, Peck H. Frequency of tooth extraction in orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod 1979;76:491–496. 5. Weintraub JA, Vig PS, Brown C, Kowalski CJ. The prevalence of orthodontic extractions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1989;96:462–466. 6. McCaul L, Jenkins W, Kay E. The reasons for the extraction of various tooth types in Scotland: a 15-year follow up. J Dent 2001;29:401–407. 7. Sayegh A, Hilow H, Bedi R. Pattern of tooth loss in recipients of free dental treatment at the University Hospital of Amman, Jordan. J Oral Rehabil 2004;31:124–130. 7 A Hatami and C Dreyer 8. Dixit L, Gurung C, Gurung N, Joshi N. Reasons underlying the extraction of permanent teeth in patients attending Peoples Dental College and Hospital. Nepal Med Coll J 2010;12:203– 206. 30. Tomar SL, Reeves AF. Changes in the oral health of US children and adolescents and dental public health infrastructure since the release of the Healthy People 2010 Objectives. Acad Pediatr 2009;9:388–395. 9. Barbato PR, Peres MA. Tooth loss and associated factors in adolescents: a Brazilian population-based oral health survey. Rev Saude Publica 2009;43:13–25. 31. Beltran-Aguilar ED, Barker LK, Canto MT, et al. Surveillance for dental caries, dental sealants, tooth retentions, edentulism, and enamel fluorosis – United States, 1988–1994 and 1999– 2002. MMWR Surveill Summ 2005;54:1–43. 10. Andrews LF. The six keys to normal occlusion. Am J Orthod 1972;62:296–309. 11. Liddle DW. Second molar extraction in orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod 1977;72:599–616. 32. Sandler PJ, Atkinson R, Murray AM. For four sixes. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2000;117:418–434. 12. Richardson ME. Second permanent molar extraction and late lower arch crowding: a ten-year longitudinal study. Aust Orthod J 1996;14:163. 33. Ay S, Agar U, Bıcßakcßı AA, K€ oßs ger HH. Changes in mandibular third molar angle and position after unilateral mandibular first molar extraction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:36–41. 13. Williams R, Hosila FJ. The effect of different extraction sites upon incisor retraction. Am J Orthod 1976;69:388–410. 34. Weerheijm K, J€alevik B, Alaluusua S. Molar–incisor hypomineralisation. Caries Res 2001;35:390–391. 14. Proffit W, Fields H. Contemporary orthodontics. St Louis: Ed Mosby Inc, 2000. 35. William V, Messer LB, Burrow MF. Molar incisor hypomineralization: review and recommendations for clinical management. Paediatr Dent 2006;28:224–232. 15. R€ onnerman A. The effect of early loss of primary molars on tooth eruption and space conditions a longitudinal study. Acta Odontol Scand 1977;35:229–239. 16. Kerr W. The effect of the premature loss of deciduous canines and molars on the eruption of their successors. Eur J Orthod 1980;2:123–128. 17. Kochhar R, Richardson A. The chronology and sequence of eruption of human permanent teeth in Northern Ireland. Int J Paediatr Dent 1998;8:243–252. 18. Elizabeth Hatton M. A measure of the effects of heredity and environment on eruption of the deciduous teeth. J Dent Res 1955;34:397–401. 19. Clements E, Davies-Thomas E, Pickett KG. Time of eruption of permanent teeth in British children at independent, rural, and urban schools. Br Med J 1957;1:1511. 20. Eveleth PB. Eruption of permanent dentition and menarche of American children living in the tropics. Hum Biol 1966;38:60–70. 21. Nonaka K, Ichiki A, Miura T. Changes in the eruption order of the first permanent tooth and their relation to season of birth in Japan. Am J Phys Anthropol 1990;82:191–198. 22. Carlos JP, Gittelsohn AM. Longitudinal studies of the natural history of caries. I. Eruption patterns of the permanent teeth. J Dent Res 1965;44:509–516. 23. Ash MM, Wheeler RC. Dental anatomy, physiology and occlusion. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1984. 24. Seale NS. The conundrum of the ‘tween’ tooth. Pediatr Den. 2013;35:490–491. 25. Todd JE, Dodd T. Children’s dental health in the United Kingdom, 1983: a survey carried out by the Social Survey Division of OPCS, on Behalf of the United Kingdom Health Departments, in Collaboration with the Dental Schools of the Universities of Birmingham and Newcastl. Great Britain, UK: Office of Population Censuses and Surveys, 1985. 26. Telli A, Aytan S. Changes in the dental arch due to obligatory early extraction of first permanent molars. Turk J Orthod 1989;2:138–143. 27. G€ ung€ orm€ ußs M, G€ ung€ orm€ ußs Z, Tozoglu S, Yavuz M. C ß ekilen disßlerdeki mevcut patolojik durumların istatistiksel olarak de gerlendirilmesi. T€ urkiye Klinik Derg 2001;3:86–90. 28. Morita M, Kimura T, Kanegae M, Ishikawa A, Watanabe T. Reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Japan. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1994;22:303–306. 29. Li S-H, Kingman A, Forthofer R, Swango P. Comparison of tooth surface-specific dental caries attack patterns in US schoolchildren from two national surveys. J Dent Res 1993;72:1398–1405. 8 36. Koch G, Hallonsten AL, Ludvigsson N, Hansson BO, Hoist A, Ullbro C. Epidemiologic study of idiopathic enamel hypomineralization in permanent teeth of Swedish children. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1987;15:279–285. 37. J€alevik B, Klingberg G, Barreg ard L, Noren JG. The prevalence of demarcated opacities in permanent first molars in a group of Swedish children. Acta Odontol Scand 2001;59:255– 260. 38. Leppaniemi A, Lukinmaa P-L, Alaluusua S. Nonfluoride hypomineralizations in the permanent first molars and their impact on the treatment need. Caries Res 2001;35:36–40. 39. Alaluusua S, B€ackman B, Brook AH, Lukinmaa P-L. Developmental defects of dental hard tissue and their treatment.In: Koch G, Poulsen S, eds. Pediatric dentistry: a clinical approach 2nd edn. Copenahgen, Denmark: Munksgaard. 2001;273–299. 40. J€alevik B, M€ oller M. Evaluation of spontaneous space closure and development of permanent dentition after extraction of hypomineralized permanent first molars. Int J Paediatr Dent 2007;17:328–335. 41. Burke F, Wilson N, Cheung S, Mj€ or I. Influence of patient factors on age of restorations at failure and reasons for their placement and replacement. J Dent 2001;29:317–324. 42. Bernardo M, Luis H, Martin MD, et al. Survival and reasons for failure of amalgam versus composite posterior restorations placed in a randomized clinical trial. J Am Dent Assoc 2007;138:775–783. 43. Opdam N, Bronkhorst E, Loomans B, Huysmans M-C. 12year survival of composite vs. amalgam restorations. J Dent Res 2010;89:1063–1067. 44. Hunter B. Survival of dental restorations in young patients. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol 1985;13:285–287. 45. Ong DV, Bleakley J. Compromised first permanent molars: an orthodontic perspective. Aust Dent J 2010;55:2–14. 46. Seddon J. Extraction of four first molars: a case for a general practitioner? J. Orthod 2004;31:80–85. € 47. Bayram M, Ozer M, Arici S. Effects of first molar extraction on third molar angulation and eruption space. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2009;107:14–20. 48. Rebellato J. Asymmetric extractions used in the t reatment of patients with asymmetries. Semin Orthod 1998;4:180–188. 49. C ß aglaroglu M, Kilic N, Erdem A. Effects of early unilateral first molar extraction on skeletal asymmetry. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2008;134:270–275. 50. Bishara SE, Burkey PS, Kharouf JG. Dental and facial asymmetries: a review. Angle Orthod 1994;64:89–98. 51. Chebib F, Chamma A. Indices of craniofacial asymmetry. Angle Orthod 1981;51:214–226. © 2019 Australian Dental Association Molar extractions 52. Vig PS, Hewitt AB. Asymmetry of the human facial skeleton. Angle Orthod 1975;45:125–129. patients with Class II malocclusions. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;120:608–613. 53. Farkas LG, Cheung G. Facial asymmetry in healthy North American Caucasians: an anthropometrical study. Angle Orthod 1981;51:70–77. 73. Novackova S, Marek I, Kamınek M. Orthodontic tooth movement: bone formation and its stability over time. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2011;139:37–43. 54. Halicioglu K, Celikoglu M, Caglaroglu M, Buyuk SK, Akkas I, Sekerci AE. Effects of early bilateral mandibular first molar extraction on condylar and ramal vertical asymmetry. Clin Oral Investig 2013;17:1557–1561. 74. Merrifield LL. Dimensions of the denture: back to basics. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1994;106:535–542. 55. Halicioglu K, Celikoglu M, Buyuk SK, Sekerci AE, Candirli C. Effects of early unilateral mandibular first molar extraction on condylar and ramal vertical asymmetry. Eur J Dent 2014;8:178. 75. de la Hoz Chois A, Yepes EO, Villarreal PV, Bustillo JM. Evaluation of dimensions of the distal alveolar bone of the second molar by cone beam after extraction of third molars. Rev Mex Ortod 2016;4:232–237. 56. Crabb J, Rock W. Treatment planning in relation to the first permanent molar. Br Dent J 1971;131:396. 76. McArdle LW, Renton TF. Distal cervical caries in the mandibular second molar: an indication for the prophylactic removal of the third molar? Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;44:42–45. 57. Conway M, Petrucci D. Three cases of first permanent molar extractions where extraction of the adjacent second deciduous molar is also indicated. Dent Update 2005;32:338–342. 77. J€ager A, El-Kabarity A, Singelmann C. Evaluation of orthodontic treatment with early extraction of four second molars. J Orofac Orthop 1997;58:30–43. 58. Shah SM, Joshi M. An assessment of asymmetry in the normal craniofacial complex. Angle Orthod 1978;48:141–148. 78. Falci SGM, de Castro CR, Santos RC, et al. Association between the presence of a partially erupted mandibular third molar and the existence of caries in the distal of the second molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012;41:1270–1274. 59. Teo T, Ashley P, Parekh S, Noar J. The evaluation of spontaneous space closure after the extraction of first permanent molars. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2013;14:207–212. 60. Moffitt AH. Eruption and function of maxillary third molars after extraction of second molars. Angle Orthod 1998;68:147–152. 61. Halicioglu K, Toptas O, Akkas I, Celikoglu M. Permanent first molar extraction in adolescents and young adults and its effect on the development of third molar. Clin Oral Investig 2014;18:1489–1494. 62. Angel E. Treatment of malocclusion of the teeth and fractures of the maxillae: Angle’s system. Philadelphia: SS White Dental Manufacturing Company, 1900. 63. Gaumond G. Second molar germectomy and third molar eruption: 11 cases of lower second molar enucleation. Angle Orthod 1985;55:77–88. 64. Monaco G, Cecchini S, Gatto MR, Pelliccioni GA. Delayed onset infections after lower third molar germectomy could be related to the space distal to the second molar. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2017;46:373–378. 65. Quinn GW. Extraction of four second molars. Angle Orthod 1985;55:58–69. 66. Peng KY, Tseng YC, Shen EC, Chiu SC, Fu E, Huang YW. Mandibular second molar periodontal status after third molar extraction. J. Periodontol 2001;72:1647–1651. 67. Coleman M, McCormick A, Laskin DM. The incidence of periodontal defects distal to the maxillary second molar after impacted third molar extraction. J Oral Maxillofac Sur 2011;69:319–321. 68. Chou YH, Ho PS, Ho KY, Wang WC, Hu KF. Association between the eruption of the third molar and caries and periodontitis distal to the second molars in elderly patients. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2017;33:246–251. 69. Stella PEM, Falci SGM, Oliveira de Medeiros LE, et al. Impact of mandibular third molar extraction in the second molar periodontal status: a prospective study. J Indian Soc Periodontol 2017;21:285–290. 70. Kugelberg CF, Ahlstr€ om U, Ericson S, Hugoson A, Kvint S. Periodontal healing after impacted lower third molar surgery in adolescents and adults: a prospective study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1991;20:18–24. 79. Toedtling V, Coulthard P, Thackray G. Distal caries of the second molar in the presence of a mandibular third molar–a prevention protocol. Br Dent J 2016;221:297–302. 80. Bishara SE, Ortho D, Burkey PS. Second molar extractions: a review. Am J Orthod 1986;89:415–424. 81. Wieslander L, Tandl€akare L. The effect of orthodontic treatment on the concurrent development of the craniofacial complex. Am J Orthod 1963;49:15–27. 82. Staggers JA. A comparison of results of second molar and first premolar extraction treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990;98:430–436. 83. Orton-Gibbs S, Orton S, Orton H. Eruption of third permanent molars after the extraction of second permanent molars. Part 2: functional occlusion and periodontal status. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2001;119:239–244. 84. Chipman MR. Second and third molars: their role in orthodontic therapy. Am J Orthod 1961;47:498–520. 85. Chhibber A, Upadhyay M. Anchorage reinforcement with a fixed functional appliance during protraction of the mandibular second molars into the first molar extraction sites. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2015;148:165–173. 86. Richardson ME, Richardson A. Lower third molar development subsequent to second molar extraction. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1993;104:566–574. da Silva GN. Subcuta87. Sim~ oes AF, Rodrigues JB, Marques SU, neous emphysema and pneumomediastinum during a tooth extraction. Acta Med Port 2018;31:435–439. 88. Salem K, Ezaani P. Radiographic evaluation of the developmental stages of second and third molars in 7 to 11-year-old children and its implicationin the treatment of first molars with poor prognosis. J Res Dent Orthod Maxillofac Sci 2016;1:1–8. 89. Faria AI, Gallas-Torreira M, L opez-Rat on M. Mandibular second molar periodontal healing after impacted third molar extraction in young adults. J Oral Maxillofac Sur 2012;70:2732–2741. 90. Nunn M, Fish M, Garcia R, et al. Retained asymptomatic third molars and risk for second molar pathology. J Dent Res 2013;92:1095–1099. 71. Montero J, Mazzaglia G. Effect of removing an impacted mandibular third molar on the periodontal status of the mandibular second molar. J Oral Maxillofac Sur 2011;69:2691–2697. 91. Livas C, Pandis N, Booij JW, Halazonetis DJ, Katsaros C, Ren YJTAO. Influence of unilateral maxillary first molar extraction treatment on second and third molar inclination in class II subdivision patients. Angle Orthod 2015;86:94–100. 72. Waters D, Harris EF. Cephalometric comparison of maxillary second molar extraction and nonextraction treatments in 92. Livas C, Halazonetis DJ, Booij JW, Katsaros C, Ren Y. Does fixed retention prevent overeruption of unopposed mandibular © 2019 Australian Dental Association 9 A Hatami and C Dreyer second molars in maxillary first molar extraction cases? Prog Orthod 2016;17:6. chronological age: a panoramic radiographic study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015;19:183–189. 93. De-la-Rosa-Gay C, Valmaseda-Castell on E, Gay-Escoda C. Spontaneous third-molar eruption after second-molar extraction in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;129:337–344. 110. Tabrizi R, Arabion H, Gholami M. How will mandibular third molar surgery affect mandibular second molar periodontal parameters? Dent Res J 2013;10:523–526. 94. Huggins DG, McBride LJ. The eruption of lower third molars following the loss of lower second molars: a longitudinal cephalometric study. Br J Orthod 1978;5:13–20. 111. Krausz AA, Machtei EE, Peled M. Effects of lower third molar extraction on attachment level and alveolar bone height of the adjacent second molar. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2005;34:756–760. 95. Gooris CGM, Joondeph DR. Eruption of mandibular third molars after second-molar extractions: a radiographic study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 1990;98:161–167. 112. Lindner RT. The third molar controversy: Framing the controversy as a public health policy issue. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999;57:445. 96. Blankenship JA, Mincer HH, Anderson KM, Woods MA, Burton EL. Third molar development in the estimation of chronologic age in American blacks as compared with whites. J Forensic Sci 2007;52:428–433. 113. Mahon N, Stassen LF. Post-extraction inferior alveolar nerve neurosensory disturbances–a guide to their evaluation and practical management. J Ir Dent Assoc 2014;60:241–250. 97. De Luca S, Pacifici A, Pacifici L, et al. Third molar development by measurements of open apices in an Italian sample of living subjects. J Forensic Leg Med 2016;38:36–42. 98. Mettes TG, Nienhuijs ME, van der Sanden WJ, Verdonschot E, Plasschaert AJ. Interventions for treating asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth in adolescents and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;2:CD003879. 99. Mortazavi H, Baharvand M. Jaw lesions associated with impacted tooth: a radiographic diagnostic guide. Imaging Sci Dent 2016;46:147–157. 100. Nelson SJ, Ash MM, Ash MM. Wheeler’s dental anatomy, physiology, and occlusion. St. Louis, Mo: Saunders/Elsevier, 2010. 114. Bui CH, Seldin EB, Dodson TB. Types, frequencies, and risk factors for complications after third molar extraction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003;61:1379–1389. € Garip Y. Anxiety 115. Garip H, Abalı O, G€ oker K, G€ okt€ urk U, and extraction of third molars in Turkish patients. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2004;42:551–554. 116. Kim Y-K, Kim S-M, Myoung H. Musical intervention reduces patients’ anxiety in surgical extraction of an impacted mandibular third molar. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2011;69:1036–1045. 117. van Wijk A, Lindeboom J. The effect of a separate consultation on anxiety levels before third molar surgery. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2008;105:303–307. 101. Richardson ME. Some aspects of lower third molar eruption. Angle Orthod 1974;44:141–145. 118. Lee KL, Corbet EF, Leung WK. Survival of molar teeth after resective periodontal therapy–a retrospective study. J Clin Periodontol 2012;39:850–860. 102. Swift JQ, Nelson WJ. The nature of third molars: are third molars different than other teeth? Atlas Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin 2012;20:159. 119. Richardson ME, Orth D. The role of the third molar in the cause of late lower arch crowding: a review. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 1989;95:79–83. 103. Steed MB. The indications for third-molar extractions. J Am Dent Assoc 2014;145:570–573. 120. Bayram M, Ozer M, Arici S. Effects of first molar extraction on third molar angulation and eruption space. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2009;107:e14–e20. 104. Almonaitiene R, Balciuniene I, Tutkuviene J. Factors influencing permanent teeth eruption. Part one–general factors. Stomatologija 2010;12:67–72. 105. Normando D. Third molars: to extract or not to extract? Dental Press J Orthod 2015;20:17–18. 106. Costa MGd, Pazzini CA, Pantuzo MCG, Jorge MLR, Marques LS. Is there justification for prophylactic extraction of third molars? A systematic review. Braz Oral Res 2013;27:183–188. 107. Mercier P, Precious D. Risks and benefits of removal of impacted third molars. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1992;21:17–27. 108. Cutilli T, Bourelaki T, Scarsella S, et al. Pathological (late) fractures of the mandibular angle after lower third molar removal: a case series. J Med Case Rep 2013; 7:121. 109. Zandi M, Shokri A, Malekzadeh H, Amini P, Shafiey P. Evaluation of third molar development and its relation to 10 121. Ay S, Agar U, Bicakci AA, Kosger HH. Changes in mandibular third molar angle and position after unilateral mandibular first molar extraction. Am J Orthod Dentofac Orthop 2006;129:36–41. _ _ _ Effects 122. Ib Yavuz, Baydasß B, Ikbal A, Dagsuyu IM, Ceylan I. of early loss of permanent first molars on the development of third molars. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop 2006;130:634–638. Address for correspondence: Amir Hatami 38 James Street Mount Gambier SA 5290 Australia Email: amh2005@gmail.com © 2019 Australian Dental Association