University of Iowa

Iowa Research Online

Theses and Dissertations

2011

Darius Milhaud's La Création du Monde: the

conductor's guide to performance

Robert Ward Miller

University of Iowa

Copyright 2011 Robert Ward Miller

This dissertation is available at Iowa Research Online: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/2746

Recommended Citation

Miller, Robert Ward. "Darius Milhaud's La Création du Monde: the conductor's guide to performance." DMA (Doctor of Musical

Arts) thesis, University of Iowa, 2011.

http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/2746.

Follow this and additional works at: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd

Part of the Music Commons

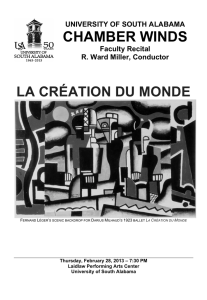

1 DARIUS MILHAUD’S LA CRÉATION DU MONDE: THE CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO PERFORMANCE by Robert Ward Miller, Jr. An Abstract Of a thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the Graduate College of The University of Iowa December 2011 Thesis Supervisor: Professor Emeritus Myron D. Welch

1 ABSTRACT Darius Milhaud’s 1923 ballet La création du monde (The Creation of the World) was and is a fascinating work for chamber ensemble. The French composer’s inventive blending of jazz harmony and compositional technique, Harlem musical instrumentation, and the discipline of cutting-­‐edge European art music remains a milestone in the cross-­‐Atlantic pollination that America’s original art form engendered in the early 20th century. All of this was accomplished before Gershwin’s ultimately better known Rhapsody in Blue. Milhaud’s progressive percussion writing in the work, as well as his combination of jazz harmonies with his own particular polytonal voice, makes the work even more stunning. However, all of these features also make the work challenging to prepare and perform. Prior to this thesis, the extant literature on La création du monde examined the work either theoretically (specifically in terms of polytonality), or historically (in terms of its relationship to the cross-­‐pollination of jazz and western art music). These publications do not provide the necessary information for a conductor and ensemble to effectively interpret and perform this work. The present study synthesizes the historical and biographical events that led to the composition of the work with the musical considerations of form and theme compounded by a foreign language score with period terminology, notation, and indications with the wind conductor as the intended audience. The purpose of this study was to collect, categorize, interpret, and synthesize the necessary information to enable a conductor to undertake this work, while simultaneously encouraging more modern conductors and performers 2 to do just that. Using historical documentation from primary sources and careful study, translation, and interpretation of available editions, this study provides the wind conductor with all of the tools and information required to prepare and conduct this work. Through this thesis, it is hoped that a new generation of conductors will be encouraged to approach, study, interpret, and program this wonderful piece of music. Abstract Approved: _______________________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor _______________________________________________________ Title and Department _______________________________________________________ Date DARIUS MILHAUD’S LA CRÉATION DU MONDE: THE CONDUCTOR’S GUIDE TO PERFORMANCE by Robert Ward Miller, Jr. A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree in the Graduate College of The University of Iowa December 2011 Thesis Supervisor: Professor Emeritus Myron D. Welch Copyright by ROBERT WARD MILLER, JR. 2011 All Rights Reserved Graduate College The University of Iowa Iowa City, Iowa CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL _________________________ D.M.A. THESIS ____________ This is to certify that the D.M.A. thesis of Robert Ward Miller, Jr. has been approved by the Examining Committee for the thesis requirement for the Doctor of Musical Arts degree at the December 2011 graduation. Thesis Committee: ________________________________________________________ Myron D. Welch, Thesis Supervisor ________________________________________________________ William L. Jones ________________________________________________________ L. Kevin Kastens ________________________________________________________ R. Mark Heidel ________________________________________________________ Robert C. Cook To Cortney Mosley, Robert Miller, Kathy Miller, Drew Miller, Joe Gibson, and Myron Welch ii …new instrumental techniques, the piano with the dryness and the precision of a drum and a banjo, the rebirth of the saxophone, the trombone glissandos that became a most common means of expression entrusted with the sweetest melodies, and the trumpet, ... the mute, … vibrato of the slide or piston, "flutter tongue"; the clarinet in the extreme upper range, with violence in the attack, a force in the sound, a technique of slipping and trilling of the note disconcerted our best instrumentalists…The strength of jazz comes from the novelty of his technique in all areas… In terms of orchestration, the use of the various instruments listed above and the development of their specialized technique have a variety of extraordinary expression. Darius Milhaud, speaking on his early impressions of jazz, in “L'évolution du jazz-­‐

band et la musique des nègres d'Amérique du nord” iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author’s thanks go to Professor Gail Wilson of Arizona State University for introducing him to La création du monde, and to the faculty and staff of The University of Iowa School of Music for their guidance and instruction in the craft of music research. Heartfelt gratitude and appreciation go to Dr. Myron Welch for his patience, wisdom, kindness, and mentorship, and for pointing out the right direction for this project. The percussion writing in this paper would not have been the same without the aid of Dr. Michael Sammons of the University of South Alabama. Thanks also to Universal Music Group for permission to utilize the score and to create a modern edition of the percussion score. Most of all, the deepest thanks go to my wife and my family for their patience and support through many years of study. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 – AN INTRODUCTION TO LA CRÉATION DU MONDE ...................................... 1 La Crèation du Monde .................................................................................................... 3 Review of Selected Literature ........................................................................................ 8 Purpose of the Study and Methodology ...................................................................... 10 Organization of the Study ............................................................................................ 11 CHAPTER 2 – BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH AND GENESIS OF THE WORK ............................... 13 Early Life and Musical Studies ...................................................................................... 13 Exposure to Jazz Abroad .............................................................................................. 15 Composition and Premiere of La création du monde ................................................. 20 Flight from War and Its Consequences for the Manuscript ........................................ 23 CHAPTER 3 – JAZZ ELEMENTS IN LA CRÉATION DU MONDE ........................................... 25 Manuscript ................................................................................................................... 25 Jazz Elements in La création du monde ........................................................................ 27 Instrumentation ........................................................................................................... 27 Rhythm ......................................................................................................................... 30 Melody ......................................................................................................................... 32 Harmony ...................................................................................................................... 34 Performance Indications .............................................................................................. 34 Form ............................................................................................................................. 36 CHAPTER 4 – INTERPRETING SCORE INDICATIONS .......................................................... 39 Instrumentation ........................................................................................................... 39 Performance Indications .............................................................................................. 45 Movements .................................................................................................................. 47 CHAPTER 5 -­‐ FORMAL AND THEORETICAL ANALYSIS ....................................................... 51 Blues Harmony ............................................................................................................. 51 Tonal Structure ............................................................................................................ 52 Form ............................................................................................................................. 53 Key Topography and Modulatory Technique ............................................................... 56 Thematic Persistence and Juxtaposition ...................................................................... 60 CHAPTER 6 – CONCLUSION .............................................................................................. 63 Recommendations for Further Study ........................................................................... 64 APPENDIX A – THEMATIC CATALOGUE ............................................................................ 66 APPENDIX B – TONAL STRUCTURE ANALYSIS ................................................................... 72 APPENDIX C – TRANSLATIONS AND INTERPRETATIONS OF SCORE INDICATIONS ............ 75 APPENDIX D – CORRECTED AND MODERN PERCUSSION EDITION ................................... 77 BIBLIOGRAPHY AND DISCOGRAPHY ................................................................................. 99 v 1 CHAPTER 1 – AN INTRODUCTION TO LA CRÉATION DU MONDE In 2004, I was studying at Arizona State University in pursuit of a Masters of Music in trombone performance. It was a continually eye-­‐opening experience for me, as my previous knowledge of repertoire for the instrument had been quite limited. One of the most interesting and intellectually stimulating classes in my course of study was the trombone repertoire convocation, in which the studio members sat listening to, and also playing, great works in the orchestral repertoire. However, it was one particular fall day that changed my life. Professor Gail Wilson, our trombone teacher, handed us a score to a work of which I had never heard: Darius Milhaud’s La création du monde (The Creation of the World). My interest was immediately piqued. Not only was this a work, unknown to me, that included trombone, but it was a French composition. Having studied French for years, I was suddenly engaged in translating the different markings and indications on the score I had been handed. The title itself was intriguing, evoking images of the primordial dark, as well as possible exploration of the Judeo-­‐Christian Eden. I became even more excited when Professor Wilson informed us that Leonard Bernstein was the conductor of the recording. Now I was really intrigued, in a way that makes me look back and laugh. “Why was I ignorant of an important work that included trombone, important enough for Leonard Bernstein to conduct it?” So went my thinking at the time, though it was certainly flawed. I was no expert on the trombone’s oeuvre, and Bernstein’s involvement, though notable, was not a magic stamp of importance on La création du monde. However, all of my intellectual 2 curiosity was as nothing compared to my emotional reaction upon hearing the recording. The immediateness, the plaintive silkiness of the opening theme in the alto saxophone, coupled with a strangely compelling counter line of parallel thirds in the strings – it was so fresh, surprising, and exotic yet familiar, all at the same time. What followed was a work that evoked memories of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, but had been written and premiered before that well-­‐known work. The jazz underpinnings to La création du monde were clear, and its adherence to a jazz ideal of raucous “shout” was obvious to me on the first hearing. The ensemble itself even evoked jazz, with a particularly sparse but varied instrumentation of playing soloistically, especially the saxophone. The addition of the strings made the piece even more novel, as the rest of the ensemble was clearly inspired by early jazz bands. A variety of trumpet mutes, glissandi, improvisatory ostinati, and “blue note” harmonies placed this firmly in the category of an early classical work in the jazz idiom. I was completely entranced, immediately grabbing a copy of the recording for myself. Since that time I have discovered the reasons why the work should have been so intriguing to me. Not only is it a brilliant chamber music composition, but it is also well-­‐

constructed, with inventive themes that use jazz in a refined and revolutionary way rather than as mere novelty. It manages to be all of these things while remaining relatively unknown to many modern conductors. Over the years, I have repeatedly mentioned the work to students, colleagues, and friends, and by and large the uniform answer has been the same – “Who? What?” I play the recordings for them, and they 3 are stunned that they have never heard of, much less heard, the composition. The vast majority of them agree that it is a masterful work, made more interesting by their previous ignorance of it. The fact that that it was written as a chamber ballet for an ensemble in which winds predominate makes it of special note, since this dance collaboration pushes the work’s sphere of influence into the adjoining Parisian arts of dance, painting, and theatre. My journey to uncover the reasons behind this obscurity, and to eventually help a new generation of conductors to discover the work, became a quest in earnest in 2007. When I presented the work in wind repertoire class at The University of Iowa, no other student in the class knew of the work. My conducting teacher, Dr. Myron Welch, looked at me and suggested then and there that I make this project my thesis. I was amazed that I had never thought of the idea myself: to narrowly study a work for which I had a genuine love, and that had very little scholarly discourse attached to it. Add the fact that my French language skills would aid in the research process, and it was a perfect match. La Crèation du Monde Before undertaking a historical and analytical study of this work, one must know the generalities and circumstances about La création du monde. The facts outlined in this introduction are expanded upon deeply and completely in the following chapters. On October 25, 1923, the Ballets Suédois debuted their new production, La création du monde, at the Théâtre des Champs Elysées. The theatre, situated on the Avenue Montaigne near the Pont de l’Alma over the Seine, had a history of famous premieres. 4 Just ten years earlier Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps had opened in the Champs Elysées to an audience that, becoming divided and agitated by their reception of the composition, broke out into fistfights and a riot that spilled into the streets. La création du monde would not have such a tumultuous premiere. With the exciting and exotic new sounds of jazz sweeping Europe, the French tastes of the season were for the usual exoticism, only now couched in the form of African primitivism. The Swiss author Blaise Cendrars, a naturalized French citizen, had published his L’Anthologie Nègre (translated by Margery Bianco as The African Saga) in 1921. In his introduction to this work, Arthur Spingarn, states that “it was not until the publication of L’Anthologie Nègre” that the true value and significance of these cultural artifacts became apparent.1 A compilation of African legends translated and edited by Cendrars, it was this very text, specifically the first chapter “Cosmic Legends,” that would be the inspiration for the ballet La création du monde. These opening pages conveyed several African creation myth tales: “The Story of Creation,” “The Story of the Beginning of Things,” “The Story of the Separation,” and “The Story of Bingo.” The first two stories were the only sources utilized in the creation of the new ballet, with the ideas of three deities creating all life from darkness and chaos forming the germ of the work’s inspiration. Beyond this connection, Milhaud’s score remained quite independent of the text premise. This was immediately apparent to early reviewers. Music critic Boris de Schloezer wrote in the 1923 Revue Pleyel: ________________________________________________________________________ 1 Spingarn, A. in The African Saga, Margery Bianco, 6 5 “The composer obviously did not think for a moment that he should ‘show’ or ‘comment’ upon this legend by having his music following a detailed text step by step.”2 What the audience heard instead was a world’s-­‐first blend of American jazz harmonies, rhythms, and conventions combined with the compositional forms and restraint of classical Western music to an extent hitherto unseen. Glissandi, “blue note” melodic and harmonic structures, and jazz rhythms were used not as mere novelties, but as a unified basis for a work that used limited motivic materials and vivid textures. La création du monde is immediately “jazzy,” with a leading alto sax voice stating the first motive in D-­‐minor over a D-­‐major ostinato, creating a blue note effect. Rhythms, while never swung, are syncopated and often repeated in hemiola patterns as “riffs.” A shout chorus forms the climax of the work, with fragments of several motives forming layers of exuberant counterpoint found in the era’s best jazz band performances. At the same time, Milhaud showed classical restraint in the number of motives used in the work. He even managed a jazz fugue in the center of the work, and the form of the entire ballet forms a symmetrical arc opening and closing with the same motivic materials. Truly this was disciplined construction of art, not a smattering of jazz riffs pasted into a ballet. The décor and costumes for the ballet must have certainly been a draw to Parisian fans seeking spectacles in African primitivism. Painter Ferdinand Léger had created as wild and frightening a landscape as he could possibly muster. Even the curtain was repeatedly changed leading up to the debut because Léger evidently could ________________________________________________________________________ 2 Schloëzer 1923, translation my own 6 not make it “frightening enough.” Jagged, boxy, and blocky lines dominated the imagery, with a focus on the earth tones of brown, green, yellow, and orange. The painter’s study of African ritual masks was interpreted through the prism of post-­‐Picasso Cubism, creating boxy alien bodies that used Africanesque symbols to imply character rather than literal realism. These costumes were bulky of course, and hindered the dancers in their movements. The dance troupe was Paris’ Swedish response to the Ballets Russes of Diaghilev -­‐ the Ballets Suédois (Swedish Ballet). The Ballets Suédois was in its third year of operation, with artistic direction by founder Rolf de Maré and choreography by Jean Börlin. Börlin himself would dance the leading role of the first Man. The remaining dancers played the role of the animals and plants created in the beginning of the world. Critical reaction was negative in the main, at least for a year. The choreography was encumbered by the costumes. The musical germ was clearly from the dance hall, not the concert hall, and Milhaud’s craft and restraint in implementing it was not immediately apparent to critical listeners. However, just as the composer would predict to his friends and colleagues, the critical reaction turned to acceptance within a year, and to praise and recognition within a decade. La création du monde would become increasingly important as its place became clearer within the history of jazz pollination of Western art music. The popular archetype in this vein, Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, did not premiere until three months later in February of 1924. Milhaud’s ballet score was a collaboration that included African imagery, dance, and mythos with its progeny jazz, and it did this all with 7 counterpoint and motivic development unmatched by Gershwin’s worthy work. While Milhaud had certainly been experimenting with jazz in such works as his 1920 shimmy for piano, Caramel Mou, the fact that he was not a studied jazz writer or commercial composer in this area makes La création du monde even more remarkable. Gershwin had been working in the fertile jazz and popular New York music scene since the age of fifteen. None of this diminishes the value or quality of Gershwin’s work, but it certainly places it in some much-­‐needed perspective. Approaching performance of La création du monde can be challenging at best, intimidating at worst. The parts are heavy in errata, though not to a crippling degree. The parts themselves are rental in today’s market, but that is not a major impediment for the serious concert programmer. While the work is in French, some simple research can uncover what instruments Milhaud intends and what his marking indicate, a task accomplished for the would-­‐be performer and conductor in this study. The wind and string instrumentation is thrifty, allowing the assembly of a small but necessarily facile ensemble. It is the percussion that can inhibit one’s decision to perform the work. Not only does it call for a large range of instruments, some of which are specialized French instruments or contemporary jazz devices no longer manufactured, but they are to be played by a single percussionist, often simultaneously. Add to this problem that Milhaud scored each drum, tambourine, wood block, and more into its own staff, to be read by one performer, and this barrier to performance becomes even stronger. Performance is rewarding in the extreme. A great chamber work, one pairing strings with the ensemble as Dvořák did in his Serenade, featuring an alto saxophone 8 soloist, jazz forms and harmonies, counterpoint and melodic construction of the highest caliber, innovative percussion writing, and a historical backdrop of Parisian exoticism and cultural hegemony at its height: all of this in one chamber masterpiece is well worth the programming, preparation, and performance, if one can understand and execute the work. That is the aim of this thesis: to allow modern conductors and performers to do just that. Review of Selected Literature All musical examples and analysis are taken from the 1929 full score edition from Editions Max Eschig. An earlier score, also published by Eschig in 1923, is included in the bibliography as a useful reference. However, it is a score reduced to four-­‐hand piano and therefore not suitable for clearly studying the percussion notation issues and instrumentation. A primary source in Milhaud’s or a copyist’s hand was not available for this study, nor was it used for any other study in the current literature. Details on the author’s exhaustive search for this primary source will be provided in Chapter 3. No complete formal analysis, thematic catalogue, or total examination of the work is available anywhere, though there are snippets and excerpt studies throughout the literature. There is a small handful of academic studies focused on La création du monde. Christine Amos wrote a 2007 PhD thesis at the University of Texas at Austin entitled “An Examination of 1920s Parisian Polytonality: Milhaud's Ballet La création du monde.” Julio Moreno Gonzalez-­‐Appling wrote a Masters Thesis at Bowling Green State University in 2007 called “The Ox in the Concert Hall: Jazz Identity and La création du monde.” While both of these papers focused exclusively on La création du monde, 9 neither of them examined the ballet in the conductor’s context, nor did they provide support for the very necessary instruction in performance practice and score interpretation. La création du monde was discussed in some lesser depth in Alyssa Gretchen Smith’s 2005 PhD thesis at The Ohio State University, “An Examination of Notation in Selected Repertoire for Multiple Percussion,” as well as in Norman Wika’s “Jazz Attributes in Twentieth-­‐Century Western Art Music: A Study of Four Selected Compositions,” written at the University of Connecticut in 2007. Milhaud’s work garnered a two-­‐page mention in Liesa Karen Norman’s 2002 University of British Columbus PhD thesis “The Respective Influence of Jazz and Classical Music on Each Other, the Evolution of Third Stream and Fusion and the Effects Thereof into the 21st Century.” La création du monde is mentioned in many more published books and articles focusing on the influence of jazz on western classical music, though not in any depth or detail. All of the aforementioned studies are admirable in their synthesis and research. However, none of them provide the necessary depth of knowledge and examination that a conductor would require to effectively study, interpret, prepare, rehearse, and perform La création du monde. The composer’s autobiography and correspondence provide some useful information in a study of La création du monde, though it rarely bears directly on this specific composition. There are several compendiums of Milhaud’s correspondence with a variety of friends and colleagues. However, these letters and notes provide very little insight into the composition, interpretation, or premiere of La création du monde. Instead, this correspondence provides clues to the timeline of the genesis of the work. 10 Even the composer’s 1953 autobiography Notes sans Musique (Notes without Music) sheds very little light on the work, though it provides useful anecdotes of the composer’s association with jazz. Purpose of the Study and Methodology As stated, the present literature on La création du monde examines the work either theoretically (specifically in terms of polytonality), or historically (in terms of its relationship to the cross-­‐pollination of jazz and western art music). These publications do not provide the necessary information for a conductor and ensemble to effectively interpret and perform this work. The present study synthesizes the historical and biographical events that led to the composition of the work with the musical considerations of form and theme compounded by a foreign language score with period terminology, notation, and indications with the conductor as the intended audience. The purpose of this study is to collect, categorize, interpret, and synthesize the necessary information to enable a conductor to undertake this work, while simultaneously encouraging more modern conductors and performers to do just that. Using historical documentation from primary sources and careful study, translation, and interpretation of available editions, this study provides the conductor with all of the tools and information required to prepare and conduct this work. Through this thesis, it is hoped that a new generation of conductors will be encouraged to approach, study, interpret, and program this wonderful piece of music. 11 Organization of the Study Chapter 1 includes an introduction and overview of the topic, review of selected literature related to the study, purpose of the study and methodology, and the organization of the thesis. Chapter 2 is a biographical sketch of the composer, Darius Milhaud, with an emphasis on the formative events that led to his composition of La création du monde. In particular, it details how Milhaud’s early exposure to jazz and his visits to Harlem jazz performances are critical to not only the form and genesis of the composition, but also its instrumentation and orchestration. This historical information is important to absorb and comprehend before undertaking the ideas found in Chapters III and IV. Chapter III builds upon Chapter 2 in its discussion of the jazz elements of La création du monde. The composition utilized contemporary jazz band forces and instrument pairing, orchestration and voicing evocative of that same genre, and compositional and formal constructions that clearly demonstrate that Milhaud used these models when constructing this work. A clear understanding of these ideas is critical to interpretation and performance of the work. Chapter 4 delves into actual foreign language concerns in the score’s instrumentation and performance indications. Many translations from French language sources, as well as research in percussion journals were used to synthesize this information. Chapter 5 provides a formal and theoretical analysis of the work. Such a study is required when determining prevalence of line in this often multi-­‐layered composition. It 12 is also necessary to understand the genesis and balance of harmonies and sonorities generated by the oft-­‐polytonal compositional techniques employed. Chapter 6 presents conclusions drawn from the above research and suggestions for future study. Appendix A contains a thematic catalogue of the work, with incipits of each theme. Appendix B displays an analysis of tonal structure throughout the entire composition. The appendix also notes the location (measure and voice) of the theme’s first appearance, as well as all other appearances of said theme. Appendix C provides a list of translations of score and instrumentation indications from the French language published score. Appendix D is a modern and corrected edition of the percussion parts. 13 CHAPTER 2 – BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH AND GENESIS OF THE WORK In studying La création du monde, it is unnecessary to recreate the complete biography of Milhaud’s long, varied, and distinguished career. The French composer’s September 4, 1892 birth to a Jewish family in Marseilles, his early career that distinguished him as a member of Les Six, his flight to America to escape the Nazi menace – all are documented in a variety of sources. Milhaud actually wrote two autobiographies. His Notes Sans Musique (“Notes Without Music”) was published in 1953, while Ma Vie Heureuse (“My Happy Life”) provided a revised and more expansive version of that earlier book in 1972, just two years before his death. Milhaud’s wife Madeleine provided additional reminiscences with interviewer Roger Nichols in his 1996 book Conversations with Madeleine Milhaud. Jean Roy wrote the 1968 reference Darius Milhaud, and Georges Beck provided the composer’s thematic catalogue in two volumes. Milhaud himself published several articles and studies, and he left a wealth of correspondence with his fellow composers, artists, and friends. All of these items are detailed in this study’s bibliography. Therefore, a detailed retelling of his life, career, and death are superfluous. However, it is important to focus on the events in the composer’s life that relate directly to the genesis of La création du monde, its provenance, and its history. Early Life and Musical Studies Milhaud began learning the violin at age seven while growing up in Aix-­‐en-­‐

Provence, taking lessons from local teacher Léo Bruguier. Darius’ father Gabriel, though 14 an export trader by profession, was an amateur musician at the family piano, and he encouraged his son’s early playing and tune making. His mother Sophie had been classically trained as a vocalist in Paris. As Milhaud noted in Ma Vie Heureuse, “…music was already a familiar friend” in his home.3 Milhaud continued his musical development on the violin throughout his school years, and before his Bar Mitzvah at the age of 13, he had already traveled to Paris several times with his cousins to take lessons with Alfred Brun at the Conservatoire du Paris. At age 13, Bruiguier directed him to study harmony, and Milhaud turned to Lieutenant Hambourg, the conductor of the local 61st Regiment band. His lessons would provide him with a solid foundation in harmony, though he found the compositional exercises the lieutenant assigned to be completely at odds with his own creative impulse and direction.4 After completing his baccalaureate in 1909, Milhaud went on to study at the Paris Conservatory. He continued his violin lessons, now with Berthelier, but found his attention increasingly drawn to concert attendance and composition. He sent many of his compositions to Paul Dukas, then the orchestra director at the Conservatory, who treated Milhaud to detailed letters of compositional criticism. Milhaud also attended composition classes with Xavier Leroux, though he once again found his own compositional inclinations and ideas were at odds with the systematic forms and processes assigned. A breaking point occurred when Leroux finally allowed Milhaud to play one of his own sonatas in class. According to Milhaud, the professor’s face “lighted ________________________________________________________________________ 3

Milhaud, Darius. Ma Vie Heureuse. 29-­‐31. 4

Ibid., 32. 15 up” as he declared, “What are you doing here? You are trying to learn a conventional musical language, when you already have one of your own. Leave the class! Resign!” Though Milhaud was understandably shaken by such bold advice, he overcame his temerity and went to study with André Gédalge at Leroux’s direction. Gédalge, who had studied composition at the Paris Conservatory with great success, was teaching privately in Paris. Upon hearing Milhaud’s work, Gédalge took the aspiring young composer into his studio, focusing his compositional creativity with a study of counterpoint, harmony, melody-­‐craft, orchestration, and composition. By 1912, Milhaud was completely devoted to composition, and discontinued his violin studies.5 This left him with no further classes or studies at the Paris Conservatory, and he settled into an apartment in rue Gaillard. From there, he would compose and travel throughout Europe with his friends and fellow artists through the years of World War I (Milhaud took refuge from the conflict in Provence with his family). It was during his retreat to Provence that Milhaud said he undertook a detailed study of polytonality, noting its presence in certain works of J. S. Bach, as well as its use by his contemporaries, such as Stravinsky. Exposure to Jazz Abroad If Milhaud’s freedom to travel and collaborate with fellow European artists were a source of joy and creativity to the young composer, then his next career move would afford him even wider and more exotic destinations. In the fall of 1915, Milhaud enlisted in the French Army Photographic Services. By December, his director had assigned him ________________________________________________________________________ 5

Milhaud, Darius. Ma Vie Heureuse, 41-­‐43. 16 as secretary to Paul Claudel, a poet and writer6 who was serving as the French Ambassador to Brazil.7 The diplomatic entourage would spend 1917 through 1918 in Brazil, where the composer witnessed the revelry and musical traditions of Carnaval. From there, the ambassadorship traveled on a diplomatic mission to New York City and Washington, D.C. Curiously, in his memoires Milhaud made no mention of listening to any American jazz while in New York in 1918, though he did listen to several symphonic and chamber performances during the visit. It was only after returning to Paris for three years that his travels would bring him the sounds of American jazz. In June of 1920, Milhaud accompanied Claudel (now the French Ambassador to Denmark) on a visit to London. Claudel had official business in Britain, and Milhaud was conducting a two-­‐week showing of his Le Bouef sur le toit. It was in London, of all places, that Milhaud would first turn his ear to jazz. In their free evenings both he and Claudel would visit the Palais de Danse in Hammersmith, where the American jazz piano act “Billy Arnold’s American Novelty Jazz Band” was giving regular performances.8 Milhaud’s memoires are strikingly colorful in his description of this new musical experience. “The new music was extremely subtle in its use of timbre: the saxophone breaking in, squeezing out the juice of dreams, or the trumpet, dramatic or languorous by turns, the clarinet, frequently played in its upper register, the lyrical use of the trombone, glancing with its slide over quarter-­‐tones in crescendos of volume and pitch, thus intensifying the feeling; and the whole, so various yet not disparate, held together by the piano and subtly punctuated by the complex rhythms of the percussion, a kind of inner beat, the vital pulse of the rhythmic life of the music. The ________________________________________________________________________ 6

Milhaud composed incidental music to some of Claudel’s plays, while the writer provided libretti for several of the composer’s operas. 7

Milhaud, Darius. Ma Vie Heureuse, 63-­‐65. 8

Francois and Contijuch. http://www.redhotjazz.com/banb.html (Accessed February 27, 2011) 17 constant use of syncopation in the melody was of such contrapuntal freedom that it gave the impression of unregulated improvisation, whereas in actual fact it was elaborately rehearsed daily, down to the last detail.”9 Milhaud’s description is so striking not because it is an accurate description of the early jazz he heard, but because it could literally describe his own ballet La création du monde. One might argue that this description could describe any “hot jazz” of that period, but Milhaud utilized those same effects in exactly the ways he described in My Happy Life. While it will be discussed in detail later in this study, in La création du monde the clarinet is utilized in the extreme upper range, the trombone’s very first entrance is a series of glissandi, and the alto saxophone is not only the leading voice but it is always breaking in from the “…whole, so various yet not disparate, held together by the piano and subtly punctuated by the complex rhythms of the percussion.” The cleverest graduate student could hardly write a better program note for La création du monde. Granted, Milhaud had the benefit of framing both experiences, the early jazz hearing and his own later composition, through the lenses of hindsight and the autobiographer’s ability to paint oneself in a most forward-­‐looking and positive light. Also, the astute reader and critic (and many critics would make this claim, as will be discussed later), might note that simply aping the tropes and “riffs” of jazz certainly would lead to such similarities. However, as examined in Chapter 3, Milhaud would create more than a caricature of jazz in La création du monde. Nearly all summarizations of Milhaud’s early jazz experiences speak of his listening to Billy Arnold in London, and then of his travels to New York jazz clubs. ________________________________________________________________________ 9

Milhaud, Darius, Ma Vie Heureuse, 98 18 However, he had a more personal connection to jazz while in London, one that was certainly just as formative as those oft-­‐mentioned hearings. While in London, he reconnected with old Conservatoire classmate and composer Jean Wiéner, who was working as a pianist in the Bar Gaya. Wiéner performed copious volumes of popular jazz music alongside Vance Lowry, a black man who played saxophone and banjo.10 Milhaud spent much of his time in the evenings listening to this music. Such a study in syncopated jazz rhythm and styling, especially performed by his old friend and classmate, must surely have been as important as being just another face in the crowd at a night club or show. Milhaud’s first venture in composing with these new sounds was his Caramel Mou for piano, a “shimmy” he composed for a 1921 Parisian avant-­‐garde concert. Caramel Mou remains available as a published piano solo, but Jean Cocteau had also written lyrics for this premiere, and its performance was accompanied by a dance by “the negro Graton.”11 However, the work is primarily a study in jazz form and rhythm, not the harmonies or melodic tropes of the genre. Milhaud himself had noted that his contemporaries had made essays of the same type, constraining themselves to “what were more or less interpretations of dance music.”12 Just as a Baroque dance suite coopted folk dance conventions and forms without forsaking standard practice harmony and counterpoint, Caramel Mou was a tentative and constrained exploration of an ________________________________________________________________________ 10

Jean Wiéner, Allegro Appassionato, 43 11

Darius Milhaud, Ma Vie Heureuse, 98-­‐99. 12

Ibid., 98. 19 exotic genre. Milhaud’s absorption of jazz in America would guide him to a more complete synthesis in La création du monde. In 1922, Milhaud parlayed another former Conservatoire connection into a travel and performance opportunity. Robert Schmitz, a Conservatoire-­‐trained French pianist living in New York City, connected Milhaud to a series of performance engagements in the city. Amidst a whirlwind of solo performances, compositional premieres, and guest conducting throughout Philadelphia, Boston, and New York City, Milhaud repeatedly made time to hear live jazz music performances. He heard Paul Whiteman’s jazz orchestra in New York City. His Boston guide, Harvard Glee Club Director Dr. Archibald T. Davison13, took Milhaud to the Hotel Brunswick specifically because he knew the French composer would want to hear the excellent jazz orchestra housed there. Milhaud met and spoke with Henry Burleigh, the African-­‐American classical composer who was making “negro spirituals” available to the art music community through his arrangements.14 However it was Yvonne George, the Belgian vocalist performing on Broadway and connected to Milhaud by their mutual author friend Jean Cocteau, who took Milhaud to Harlem to hear true jazz performed by black musicians.15 According to both Milhaud’s autobiography and Lunel’s biography, the “white snobs” had not yet discovered Harlem, and Milhaud and his colleagues often found themselves the only whites in sight on multiple outings to hear jazz performed in the black neighborhood. As often as he could, Milhaud went to bars, dance halls, and ________________________________________________________________________ 13

The Harvard Glee Club – History, http://www.harvardgleeclub.org/info/history (Accessed February 27, 2011) 14

Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans: A History, 284. 15

Darius Milhaud, Ma Vie Heureuse, 109. 20 theaters, noting that in “some of their shows, the singers were accompanied by a flute, a clarinet, two trumpets, a trombone, a complicated percussion section played by one man, a piano, and a string quintet.” An alto saxophone replaced the viola in the string quartet, and a string bass was added.16 The show to which he referred was Maceo Pinkard’s17 musical comedy Liza, and that instrumentation would be nearly duplicated in La création du monde. The inclusion of these jazz orchestrations in the ballet is discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. Composition and Premiere of La création du monde His experiences with authentic jazz in New York left Milhaud “more than ever…resolved to use jazz for a chamber-­‐music work.”18 Upon returning to France in April of 1923, Milhaud moved into an apartment at 10 Boulevard de Clichy, near the Pigalle Plaza. There, he immediately began collaborating with the artist Fernand Léger and the author Blaise Cendrars on a new ballet that Rolf de Maré had commissioned for his Ballets Suédois.19 The Paris art world of the early 1920s was in the grip of Primitivism, and African art and legend provided the perfect font of exoticism from which to sip. Just one year earlier in 1921, Cendrars had published Anthologie Nègre, a collection of African myths, some regarding the creation of the world. Thus, the three artists decided to create a ballet based on these myths. Cendrars could utilize his African ________________________________________________________________________ 16

Darius Milhaud, “L’evolution du jazz-­‐band….,” Le Courrier Musical, May 1923, 101. 17

Three years later, in 1925, Pinkard would compose the hit that would live on as a basketball meme -­‐ Sweet Georgia Brown 18

Darius Milhaud, Ma Vie Heurese, 110. 19

Ibid., 116-­‐117. 21 myths, Lèger could design African-­‐inspired primitive scenery and costumes, and Milhaud could utilize the instrumentation and styling of jazz, Africa’s musical voice in Western music. With audiences seeking “African” spectacle, it was clearly a smart business move as well as artistic decision. Milhaud’s new apartment was located less than two miles from the Théâtre des Champs-­‐Élysées where the ballet would premiere. That premiere came on October 25, 1923, and the results were mixed. Milhaud consistently stated in his memoires and other interviews that the very critics who dismissed the score of La création du monde as vulgar dance-­‐hall music were praising that same work a decade later for its skillful incorporation of jazz elements. However, the value of Milhaud’s score was immediately apparent to some reviewers. The German expatriate composer Boris de Schloezer was present for the opening run of La création du monde, and wrote his initial reactions in a 1923 edition of La Revue Pleyel: The Creation of the World! – At this title, I confess, I was somewhat frightened. It seemed to me heavy and pretentious. And reading the program only deepened my fears. I was expecting a music clearly tending to be descriptive and saturated with this Negro exotic of which we are already tired. It is not so, happily. We heard an orchestral work, a poem very well built, a perfect symmetry and it delighted me... One could say that between the poem by Milhaud and the legend of Blaise Cendrars, there is no point of contact ... as if we care! We're not going to the Champs-­‐Élysées to attend the realization of the sound of the creation of the world, but to hear a musical. It has its own charm: it acts directly. It is composed of various elements -­‐ classic polyphony, melodies and sentimental Negro rhythms -­‐ but it bears the mark of the personality of its author. This style, which is based upon so many heterogeneous 22 elements, also seems to me EXTREMELY characteristic to our epoch…The decors of Leger were very pleasant.20 While Milhaud certainly had the possibly sympathetic ear of a fellow composer and musician in this review, it is important to note that the review was certainly positive. The opening run of La création du monde was by no means a failure or unsuccessful. There are hints, though, that it was the dance choreography and performance that may have limited its popularity. Milhaud himself wrote that “[d]espite all the praiseworthy efforts by the Ballets Suédois, and all the esteem in which they were held, the Ballets Russes achieved a greater technical perfection.”21 De Schloezer, though clearly a musician focused on the score, took time to mention the quality of Léger’s décor and the influence of Cendrars text; he failed to mention a single word regarding the actual dance, its choreography and execution, or the costumes that Léger had designed. Milhaud similarly neglects any mention of the choreography or costumes in Ma Vie Heureuse, while praising Léger’s scenery. In his book Ballets Suédois, Pascale De Groote states: The weaknesses of the Ballets Suédois, that were the main reason for their brief existence, are mentioned in numerous press articles. The location that de Maré had chosen for their performance, the exclusive Théâtre des Champs-­‐Elysées, automatically attracted followers of the Ballets Russes. After all, it was in the same theatre that Diaghilev had caused a commotion with Le Sacre du Printemps and other innovating creations…One of the most striking weaknesses was the low quality of the dancers.”22 ________________________________________________________________________ 20

Boris de Schloezer, “Au Théâtre des Champs-­‐Élysées : { La Création du monde } de Darius Milhaud [Analogie avec la légende de Blaise Cendrars],” Revue Pleyel. 1923, 21-­‐

22. (Translation my own) 21

Darius Milhaud, Ma Vie Heureuse, 121. 22

Pascale de Groote in Ballets Suédois, 87. 23 Gilson MacCormack, a reviewer for the London-­‐based Dancing Times, wrote of the Swedish troupe in 1924 that “every star dancer’s performance was of a lower level than that of any corps de ballet-­‐dancers with the Ballet Russes.”23 Beyond some revival performances and novelty recreations of the ballet in the following decades, the musical score of La création du monde would prove to be the only lasting portion of the production. Flight from War and Its Consequences for the Manuscript Two years later, in 1925, Darius Milhaud would marry his cousin Madeleine Milhaud. Madeleine was ten years his junior and a budding actress. The couple would have a life-­‐long and happy marriage, augmented by the birth of their only child Daniel in 1930. Daniel would go on to be a successful painter and sculptor. The 10 Boulevard de Clichy apartments would be their family home until the threat of war and German Fascism forced the Milhauds to flee. Darius Milhaud’s Jewish heritage would prove central in both the history of the manuscript source for La création du monde, and in his and Madeleine’s choice to leave France and finally settle in America. The encroaching threat of Nazi Germany forced the couple to flee with their son in 1939, arriving in America in 1940. In the ensuing Nazi occupation, the German agents made it very clear that they knew of the composer’s Jewish heritage and of his public repudiation of the fascist agenda. Armand Lunel wrote in his 1992 biography Mon Ami Darius Milhaud: ________________________________________________________________________ 23

MacCormack, Gilson in Dancing Times, 12, 1924. 24 “But Milhaud didn’t know just how much he was at the forefront of those artists who perpetuated the condemnation of Hitler. During the occupation of Paris, his apartment was, to employ a euphemism, visited by the Nazis, emptied of all his music and charming collections by burning them in the fireplace, and between his photo and that of his wife, a score of Parsifal was placed!“24 It is important to note that this anecdote of Wagnerian admonishment only appears in Lunel’s writing. Neither Milhaud nor Madeliene mentioned it in their interviews or memoires. And Milhaud himself called his friend Armand Lunel a writer of “vague, excessively lyrical and slightly extravagant prose poems” in Ma Vie Heureuse (though this was a description of a very young and immature Lunel).25 One certainly does not wish to cast aspersions on Lunel’s credibility, but simply note that the story is given singularly and secondarily. If it was true, Milhaud’s Jewish lineage, as well as his outspoken protest of German wartime policy, did not go unnoticed in the Nazi ranks; the invading forces made sure to leave a very clear message in his former abode. The great tragedy of this event however, was the burning of the composer’s manuscripts and collections. It was in that chimney that the primary source of La création du monde most likely met its end. “Most likely” is the closest this author has come to a definitive location for Milhaud’s manuscript for this ballet score. The issue of a primary source, or lack thereof, is discussed in Chapter 3. ________________________________________________________________________ 24

Lunel, Armand in Mon Ami Darius Milhaud, 96. (translation my own) 25

Milhaud, Darius, Ma Vie Heureuse, 36. 25 CHAPTER 3 – JAZZ ELEMENTS IN LA CRÉATION DU MONDE Manuscript Before beginning discussion and analysis of the score, it is important to note the source. In no thesis, report, biography, catalogue, article, or book has this author found mention of Milhaud’s original score for La création du monde. While it is understandable that no prior researcher has found this primary source, it is a definite “blind spot” in the literature that no detailed account of its possible provenance has been sought and/or published. Neither Milhaud nor his wife mentioned the location of the ballet manuscript in any interview or published correspondence. The Ballets Suédois’ founder Rolf de Maré used his folded troupe’s library and files to found les Archives Internationales de la Danse, a collection within the Bibliothèque nationale de France that still tours and exhibits today; the score is not in its holdings. The score does not reside in the National Library of Sweden, the British Library, the Bibliothèque nationale de France, nor any other collection indexed by the union catalogue WorldCat. The Répertoire International des Sources Musicales catalogue holds no references to any manuscript of La création du monde. Milhaud’s private collections at Mills College do not include the score. Universal Music Group -­‐ the conglomerate who appropriated Ricordi, who annexed Editions Durand, which bought Editions Max Eschig, the Parisian editor and publisher of the printed score – does not hold the manuscript in its archives. All of this is stated with the author’s fervent hope that no other researcher will follow these same dead ends in seeking out a primary source in the composer’s hand. While it cannot be certain that the 26 original score was burned in that Parisian fireplace, it appears to be the most likely resting place of the manuscript. Though a primary source was not available for this or any other study, the firm of Editions Max Eschig served as musical editor of the original production and parts, and his Parisian publishing house provided the first printed and published editions of the score. The score’s first publication was a four-­‐part Eschig reduction for four-­‐hand piano. While this score is not effective for study of the instrumentation, especially the percussion, it is notable in that it was made available in 1923, the very year that La création du monde premiered. Eschig’s full score, complete with the percussion parts, was published in 1929. The fact that the editor of the original production also served as the publisher of these first editions lends a strong level of credibility as to these scores’ accuracy and fidelity to Milhaud’s manuscripts. Therefore, the 1929 score published by Editions Max Eschig serves as the source in all analysis and discussion throughout this study. Indeed, the only published errata from the score are in the percussion parts26, an understandable error given that Milhaud, like his contemporaries, wrote every percussion instrument into its own staff, be it a wood block or a snare drum. Such a bewildering wash of notes, sometimes connected by stems and beams across staves, would easily lead to such a copyist’s error, and the obstacle of reading this kind of notation is discussed and eliminated in Chapter 4 and the appended modern percussion ________________________________________________________________________ 26

See Girsberger “The Problem With the Parts.” Percussive Notes 38 (2000): 55-­‐59. 27 edition. With source firmly established, one is free to explore the jazz elements within La création du monde. Jazz Elements in La création du monde As discussed in Chapter 2, Milhaud was inspired by the American black comedy Liza and its jazz pit orchestra. While modeling the instrumentation on this jazz ensemble was important for recreation of jazz timbres and voicings, it was also important that the instruments used be readily available by accomplished French performers. The only characteristic “jazz” instruments called for were the alto saxophone, the string bass, and the bass drum with pedal and attached cymbal crasher. Also, the pit at Théâtre des Champs-­‐Élysées is only large enough for a small orchestra. Finally, there can be no doubt that economic considerations were important as always, and a reduced ensemble, including one percussionist performing a multitude of instruments, could only have helped to improve “the bottom line.” Like the ballet’s thematic selection, the performing forces were yet another sensible confluence of artistic endeavor and practicality. Milhaud manipulated the compositional elements of instrumentation, rhythms, melodies, harmonies, performance technique indications, and form to provide the jazz in this ballet. Instrumentation When discussing the instrumentation of La création du monde, it is important to begin with the “note d l’auteur” (“note from the composer”) published in the opening of the score: “This work should be performed, in regards to the instrumentation, as indicated in the score, without doubling the strings.” Milhaud, like any composer, would 28 have expected (at least hoped for) future performances of his work in a variety of locations and settings, many of them unbound by the space requirements of the Théâtre des Champs-­‐Élysées. However, he had stated that he intended to incorporate jazz into a “chamber work.”27 Multiples of strings, perhaps employed by a future overzealous musical director, would certainly begin to press the ensemble beyond the limits of a “chamber” group. This was important in that authentic jazz, as Milhaud had determined, was itself a genre limited to the chamber ensemble. It was small combos of two or more in a bar, or at most the azz bands he heard in Harlem theatres and dance halls. Milhaud respected the musicianship and craft of the Paul Whiteman orchestras of the jazz world, but that was not authentic in the Frenchman’s eyes. But listen seriously to a jazz band like that of Mr. Billy Arnold or Mr. Paul Whiteman. Nothing is left to chance, everything is applied with perfect tact, and the measure and balance are those of a musician who knows the wonderful possibilities of each instrument.28 To Milhaud, true jazz featured the individual voices of the instrumentalists performing a raucous, spontaneous outpouring of emotion within a sound musical framework. La création du monde would not feature any chord changes open to improvised solos, but Milhaud’s desired effect was this bona fide restrained cacophony, not the clock-­‐work precision of white jazz. All of these elements were important in Milhaud’s admonition about multiplying the strings employed, but there was another concern. Milhaud clearly intended the winds to be the foremost voice in La création du monde. ________________________________________________________________________ 27

Milhaud, Darius. Ma Vie Heureuse, 110. 28

Milhaud, Darius. "L'évolution du jazz-­‐band et la musique des nègres d'Amérique du nord." Le Courrier Musical. (May 1929), 163. 29 Increasing the number of strings would unbalance the ensemble and shift the ear to the strings, a section that does not play its usual ensemble-­‐leading orchestral role in La création du monde. The viola has been replaced by the alto saxophone, which plays the leading role in the work. The cello has been augmented by the string bass, a staple of the jazz rhythm section. The piano never introduces any new thematic material, and instead plays the role of rhythmic and percussive support more familiar to the “comp” or rhythm pianist in a jazz band.29 The violins only introduce a new theme once, the opening of Movement III; the rest of the work they are relegated to the same role as the piano. The same can be said for the cello, which introduces Theme 4 in the opening of the first movement. This is not to say that the strings and piano never carry important melodic materials, only that they are mostly middle and background voices throughout the score’s textures. Increasing the numbers of strings would focus the audience’s ear on instruments that are not the leading voices in this ballet. This sort of scoring had been firmly established by some of the greatest compositional names in Western music. Mozart’s Serenade No. 10 “Gran Partita” was a wind dectet with the addition of a string bass. Dvořák’s Serenade in D Minor, Opus 44, was a wind nonet with a bass line enhanced by the inclusion of a cello and string bass. Milhaud’s La création du monde provided yet another entry worthy in this genre.

The instrumentation of Milhaud’s ballet is further connected to jazz through the percussion writing. He recreated the “complicated percussion section played by one ________________________________________________________________________ 29

Gonzalez-­‐Appling, Julio Moreno. The Ox in the Concert Hall: Jazz Identity and La Création du Monde, 48. 30 man”30 he had seen in Harlem with a multitude of percussive sounds scored for one performer: tambour de basque, metal block, wood block, crash cymbals, snare drum, medium/tenor tom, tambourine, pedaled bass drum with a detachable cymbal, and five timpani. Such vast sonic resources at the hand of a single percussionist are evocative of the jazz set drummer, who conjures color from rim shots, brush strokes, cowbell clangs, and a host of overtones on cymbals struck anywhere from the crown to the edge. In total, Milhaud’s prescribed ensemble was, on multiple levels, a kindred spirit to the jazz bands of Harlem. Its economy of size, focus on the wind voices, assignment of the piano and strings to rhythmic roles, and plethora of percussion timbres – all of these orchestration choices would have been instantly familiar to any authentic American jazz performer or listener. The actual performance practice concerns arising from the prescribed instrumentation, as well as other questions regarding score indications and translations, is discussed in detail in Chapter 4. Rhythm Characteristic rhythm being such a fundamental and unique facet of jazz music, Milhaud utilized this element to recall the genre’s sounds. However, it should be noted that actual “swing,” with a compound triplet feel serving as the subdivision in lieu of “straight” eighth notes, does not occur in La création du monde at any point. Instead, syncopation and motive fragments in hemiola are used to punctuate the work’s jazz underpinnings. Throughout this and other chapters in the study, refer to the Thematic Catalogue in Appendix A for a listing of themes and their incipits. ________________________________________________________________________ 30

Milhaud, Darius. Ma Vie Heureuse, 110. 31 The opening theme (Theme 1) presented in the overture by the alto saxophone, demonstrates no jazz elements. It is the trumpets at Rehearsal 2 who present syncopation for the first time with Theme 2, with the characteristic syncopated style reinforced by tonic accent. Theme 2 appears multiple times in the overture, including a pure rhythmic form repeated in multiple pitched and unpitched percussion instruments. Also, Milhaud altered Theme 2 to create the rising line of Theme 8, introduced and employed repeatedly in Movement III. Theme 4, which is the subject of a fugue in Movement I, contains numerous consecutive pitches off of the downbeat, especially in the theme’s closing section. The fugue’s countersubject, Theme 5, features multiple repeated figures that open on the second half of the downbeat. Like Theme 1, the syncopation is emphasized by tonic accent; like the Theme 4 fugue subject, the theme’s closing figure includes consecutive notes placed in off beats. Syncopation is used in every measure of Theme 10, introduced by the violins in the opening of Movement III. Syncopation are employed in the lengthy Theme 12 introduced by the clarinet to open Movement IV, the ballet’s closing movement. The use of syncopated rhythm was a jazz facet being explored by multiple Parisian composers. Erik Satie’s Rag-­‐time du paquebot (1917) and Stravinksy’s Octet and Concerto for Piano (both in 1923) were just a tiny but representative portion of the new compositions utilizing the new jazz and dance rhythms that had arrived in Europe. Milhaud’s use of hemiola also creates a jazz feel. For example, Theme 4a is utilized as a closing section to fugue subject statements and as its own motive throughout the work. It is labeled in this study as such, because it is derived from the 32 figure in measures three and four of Theme 4. It is also transformed by the use of repetition in a hemiola pattern. The dual result is a syncopation caused by tonic accent, and the effect of a jazz improvisational soloist’s “riff.” Theme 4a is found in multiple forms throughout the work, often in augmentation. Percussion and percussive effects sometimes highlight these hemiola, as in four bars before Rehearsal 31. Melody Milhaud, going beyond jazz rhythm, employed the “blues” mode in his scoring for La création du monde. Not all of the melodies in La création du monde incorporate jazz rhythms or modes. While a melodic construction’s underlying harmony might imply jazz, only the creation of a tuneful line incorporating syncopation and/or “blue” notes could lead to a jazz melody. The “blues,” beyond the harmonic form employed in the genre, is an artificial scale employing a root ascending to a minor third, perfect fourth, augmented fourth, perfect fifth, and minor seventh. Mixing the “blue notes” of the minor third, augmented fourth, and minor seventh with the traditional major scale generates the characteristic harmonic and melodic features of jazz. In his article “L'évolution du jazz-­‐band et la musique des nègres d'Amérique du nord,” Milhaud cited the blues as an important element in jazz melody. Since jazz was first heard here, its evolution has been considerable. An outpouring of sound was followed up by a remarkable enhancement of melodic elements: the period of the ‘blues.’ The bare melody, supported 33 by very crisp and simple rhythmic, percussion barely discernible, more and more interior.31 The blues appears in multiple motives throughout La création du monde. Theme 4 marks the first appearance of the blues mode in the ballet’s melodies. Anchored in a D-­‐major tonality, Theme 4 mixes both F# and F natural (once spelled as E#), borrowing from the major and blues modes. The minor seventh, C, is also employed. The countersubject, Theme 5, is similarly based in the blues mode. Centered on E major, G naturals (sometimes spelled as Fx) and D naturals abound, freely mixing with the G#’s and D#’s of the major mode. Theme 7, introduced by the oboe in the second movement, is centered on the key of F major, but features tonically accented Eb’s – the flat seven. Theme 11, centered in F# major and again introduced by the oboe, presents multiple flat sevenths (E naturals) and minor thirds (A naturals). Theme 12, presented by the clarinet, is also in F# major32, and it contains multiple minor third and seventh scale tones. The fifth measure of Theme 13, the work’s final theme, features mixing of the sub-­‐tonic and supertonic in the key of F#, with both E natural and E# being used to lead into the tonic. All of these blue notes imbue the melodic material in La création du monde with a thoroughly “jazzy” character. The use of these altered chord tones also generated characteristic jazz harmonies. This harmony was further enriched through the related technique of polytonality. ________________________________________________________________________ 31

Milhaud, Darius. “L'évolution du jazz-­‐band et la musique des nègres d'Amérique du nord,” Le Courrier Musicale, 164. (Translation my own) 32

The clarinet part presents this theme in Ab (Gb concert pitch), but the rest of the score and parts present this section in F# major 34 Harmony It is important to note that the use of blue notes is a form of polytonality. Specifically, it is a mixture and juxtaposition of a major mode with its natural minor mode. When a “blue note” is employed over the major mode, then the result is the extended tertiary harmonies that constitute jazz sonorities. For example, a D major chord in the harmony, paired with a “blue” F-­‐natural and C-­‐natural, creates a (sometimes misspelled) D dominant 7 sharp 9 sonority. These techniques can create multiple sonorities, including dominant seven chords utilized as a stable tonic cadential resting point. Milhaud composed La création du monde using this blues polytonality, as well as his own particular polytonal voice and technique. Milhaud’s skill with and employ of polytonality has been well documented. The composer wrote articles in which he described his self-­‐perceived position in the spectrum of “Latin” (polytonality) and “Teutonic” (atonality) schools of thought that had arisen from 19th century chromaticism; the most representative of these articles are “Polytonalité et Atonalité” in Revue Musicale (Volume IV, number 4, 1923) and “L’Évolution de la musique modern à Paris et à Vienne” in North American Review (April, 1923). A detailed analysis of harmony and polytonality in La création du monde is provided in Chapter 5 and supplemented in Appendices A and B. Performance Indications Jazz sounds were novel to the traditional Western ear, and not only because of the new melodic and harmonic extensions or the syncopated rhythms. Jazz featured extended timbres and playing techniques that created new colors and sounds. Milhaud 35 himself noted this important feature in the jazz music being heard in Europe when he composed La création du monde. In “L'évolution du jazz-­‐band et la musique des nègres d'Amérique du nord,” Milhaud stated: …new instrumental techniques, the piano with the dryness and the precision of a drum and a banjo, the rebirth of the saxophone, the trombone glissandos that became a most common means of expression entrusted with the sweetest melodies, and the trumpet, ... the mute, … vibrato of the slide or piston, "flutter tongue"; the clarinet in the extreme upper range, with violence in the attack, a force in the sound, a technique of slipping and trilling of the note disconcerted our best instrumentalists…The strength of jazz comes from the novelty of his technique in all areas… In terms of orchestration, the use of the various instruments listed above and the development of their specialized technique have a variety of extraordinary expression.33 None of these techniques were entirely new. Flutter tonguing had certainly been used before. The clarinet had been scored in its extreme upper range well before jazz. Mutes and glissandos were not a jazz invention. However, the continuous and frequent use of these elements for expressive purposes, not just for the use of effect or novelty, was a touchstone of jazz writing and performance. Milhaud clearly understood this and incorporated these techniques into his score for La création du monde. The glissandi appear in the trombone during its very first entrance early in the overture, and they continue to appear in that voice throughout the work. This technique is complimented by that “slipping and trilling of the note” of which Milhaud wrote – ascending grace notes lilting into short pitches in the piano and saxophone, and ornamented upper neighbor tone grace notes in the flute, oboe, and trumpet. Milhaud indicated flutter tonguing in the flute, clarinet, and trumpet parts. It should be noted, ________________________________________________________________________ 33

Milhaud, Darius. “L'évolution du jazz-­‐band et la musique des nègres d'Amérique du nord,” Le Courrier Musicale, 163. 36 however, that these effects always occur at soft dynamics and legato passages. This effect is never a raucous, forte “growl.” The jazz penchant for multiple timbres through the use of mutes was carried throughout La création du monde, though not to the degree that was possible. Only the violins and trumpets have indications of either “Sourd.” (sourdine, “mute” for the strings and trumpet), and the horn part calls for “bouché” (“corked,” that is, “stopped”). The trombone part does not contain mute instructions. Milhaud did not call for cup mutes, hat mutes, harmon mutes, or any other timbre-­‐altering devices common in jazz performance. Milhaud certainly applied the upper range and forceful attack to the clarinet parts, as well as the flute parts. Both instruments are used percussively in the upper register in the fourth movement (in the “shout” section discussed below). Using repeated pitches in the upper register, all four voices continuously strike the same dissonant sonority in accented time with the percussive rhythm. Form The form of La création du monde places it firmly in the court of contemporary jazz music. Milhaud created this connection through the use of cyclic composition and the jazz convention known as a “shout” chorus. The composer created intricate relationships between many of his themes, often through the use of fragmentation and derivation. Themes appear in multiple movements, and often in juxtaposition to one another. As stated above, this lends itself to the jazz “riff” model. According to the New Grove Dictionary of Music, a riff is defined as: 37 In jazz, blues and popular music, a short melodic ostinato which may be repeated either intact or varied to accommodate an underlying harmonic pattern. The riff is thought to derive from the repetitive call-­‐and-­‐

response patterns of West African music, and appeared prominently in black American music from the earliest times. It was an important element in New Orleans marching band music (where the word ‘riff’ apparently originated), and from there entered jazz, where by the mid-­‐

1920s it was firmly established in background ensemble playing and as the basis for solo improvisation. Riffs also appeared in the accompaniments of many early blues, being particularly suited to their repeating structure. The conflict between an unvaried riff pattern and the changing harmonies of the blues progression became one of the most distinctive features of the blues and its derivatives.34 Milhaud’s cyclic composition technique, with themes continually returning in whole and/or fragment to be layered with other themes and changing harmonies, creates the effect of riff-­‐based jazz composition and improvisation. For example, the climax of the work, beginning at Rehearsal 46, layers Themes 4, 4a, 5, and 12 simultaneously and throughout multiple trading voices. All of the themes were introduced earlier in the ballet, with Themes 4, 4a, and 5 introduced in the jazz fugue of Movement I. As stated earlier, many of the work’s themes are simply riff-­‐like fragments derived or transformed from the other themes. It is also this same section at 46 that utilizes another jazz convention – the “shout chorus.” A “shout chorus” is a loud, spirited, climactic chorus in a performance by a big band, in which the brass section leads the whole ensemble.35 ________________________________________________________________________ 34

J. Bradford Robinson. "Riff." In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music

/23453 (accessed February 13, 2011). 35

"Shout." In The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, 2nd ed., edited by Barry Kernfeld. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.proxy.lib.uiowa.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music

/J408400 (accessed February 13, 2011). 38 One could not write a better description of the climax at 46 in La création du monde. Through the raucous layering of multiple riffs (themes) across changing harmonies, and through simplified phrasing structure reduced to ostinato, Milhaud created the perfect analog to a jazz climax. All of these voices, playing with soloistic abandon, are masterfully combined to create the effect of an improvisational New Orleans jazz shout chorus. Taken as a whole, the jazz effects Milhaud employed in La création du monde took the work far beyond a mere dalliance in jazz rhythm or form. The work became a clear fusion of traditional Western art music and authentic African-­‐

American jazz. Milhaud noted in his memoires that upon his first hearing of jazz, he noticed that the music “was of such contrapuntal freedom that it gave the impression of unregulated improvisation, whereas in actual fact it was elaborately rehearsed daily, down to the last detail.”36 The likes of Paul Whiteman and company sought to apply jazz harmony, rhythm, melody, and novel technique to a large orchestral model while retaining the traditional restraint and control found in those ensembles. Milhaud, on the other hand, created the illusion of freedom, of riff and improvisation, of spontaneity to the audience’s ear while still adhering to rigid form and internally established harmonic principles. In attaining this goal, Milhaud placed himself in the very realm of jazz he sought to inhabit. ________________________________________________________________________ 36