Advanced Thermodynamics

Course Administration

1

Advanced Thermodynamics

Unit Structure

The Virial Equation of States

Introduction

1

basic thermodynamic relations; phase

behaviour and phase diagrams

Cubic Equation of States

5

Advanced Equation of States

Process Thermodynamic

2

3

4

Applications of basic concepts to: Gas

compression; Refrigeration; Gas

liquefaction and Power generation cycles

Assignment: hydrogen liquefaction

Corresponding States and

Activity Coefficient Models

Phase Equilibrium,

and Flash Calculations

6

Models for Flow Assurance:

Solids and Hydrates

Thermodynamic Models:

7

Models for Transport Properties

8

Review and Mock Exam

Introduction: Statistical mechanics; the

partition function; the perfect molecular gas

and the intermolecular pair potential

2

Other information

Unit Delivery:

2hrs * 11 lectures + 2hrs

* 10 practical sessions

•

•

•

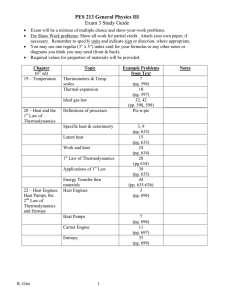

Unit Assessment:

2 hour final exam: 60 %

1 assignment (group): 20 %

1 in-class test: 20 %

Advanced Thermodynamics

Tools:

Multiflash, Refprop

Excel Sheets and

Aspen Hysys

In-class test: Mixture of Multiple Choice and Calculation Qs

Assignment: process design of hydrogen liquefaction

Lecture recordings

• Lectures will be recorded

• Recording of practical sessions is not possible in the

computer lab

• 2013 Lectures available on LMS

Lecturer & Co-ordinator; Dr Saif Al Ghafri; office 2.08; saif.alghafri@uwa.edu.au

consultation by appointment: arrange via email

3

Text books

Advanced Thermodynamics

Recommended texts (short-hand author reference in bold)

1) Assael, Trusler & Tsolakis. "Thermophysical Properties of Fluids: An Introduction

to their Prediction"

2) Prausnitz, Lichtenthaler, de Azevedo. "Molecular Thermodynamics of Fluid-Phase

Equilibria"

4

Advanced Thermodynamics

Do Accurate Property Models Actually Matter?

Relevance of property models is controversially discussed in

scientific literature

Example: Booster compressor, LNG-like mixture

m1 = 10 kg/s

T1 = 280 K

p1 = 20 MPa

SRK

r1 = 181.7 kg/m3

EOS-LNG

r1 = 191.4 kg/m3 Dr1 = 5.1%

P12

P12 = 2.346 MW

P12 = 2.334 MW

h s = 0.88

p2 = 70 MPa

Methane

Ethane

Propane

Nitrogen

0.90

0.06

0.02

0.02

c2

u2

DV = -5.1%

Blade

c1

r2

u1

r1

slides courtesy of professor Roland Span

DP12 = -0.5%

w

5

Advanced Thermodynamics

Do Accurate Property Models Actually Matter?

Relevance of property models is controversially discussed in

scientific literature

Example: Pre-cooling of a LNG-like mixture

mLNG = 10 kg/s

pLNG = 10 MPa

T1,LNG = 306 K

T2,LNG = 236 K

T2,Cool = 200 K

pCool = 1 MPa

Methane

Ethane

Propane

Nitrogen

0.90

0.06

0.02

0.02

Ethane

0.70

n-Butane

0.30

T1,Cool = 280 K

SRK

mCool = 5.11 kg/s

EOS-LNG

mCool = 5.28 kg/s Dm = 3.1%

The more detailed process simulations are,

the more relevant accurate property models become!

slides courtesy of professor Roland Span

6

Advanced Thermodynamics

The Laws of Thermodynamics

Some slides courtesy of professor Martin Trusler-ICL

7

Advanced Thermodynamics

What is Thermodynamics

An experimentally-based science that, without reference to

the microscopic nature of matter, establishes the

relationships among the variables describing systems at

equilibrium.

Laws of Thermodynamics are observed facts, not theories

based on models. The science of Thermodynamics is the

logical framework based on the application of these laws.

According to Einstein, Thermodynamics is:

“the only physical theory…that will never be overthrown…”

8

Advanced Thermodynamics

Compression Work: Closed System

• Gas contained within pistoncylinder assembly

pext

dx

pext +

dpext

• Massless and frictionless piston

• External pressure pext keeps

piston stationary: force is pextA

V

W -

V-dV

V2

V1

pext dV

• Increase pext by dpext and piston

moves down by dx.

• Volume changes by dV = -Adx.

• Work done is dW - pext dV

9

Advanced Thermodynamics

Reversible Compression

m

pa

pext

• If the piston is frictionless and the

compression is carried out slowly

then:

• p = pext throughout process and

• Work is:

V2

W -

p

p

(a)

(b)

V1

p dV

• Process said to be reversible

• In (b) pext = mg/A + pa and have basis

for primary pressure measurement

10

Advanced Thermodynamics

First Law of Thermodynamics

• Energy may be transferred to a closed system from

the surroundings as heat Q and/or work W

• Conservation of total energy requires that the system

energy increases by the total amount of energy

transferred from the surroundings no matter how it is

transferred

• It follows that there exists a state function U such

that:

DU Q W

First Law

dU dQ dW

11

Advanced Thermodynamics

Enthalpy

Constant

pressure p

Freely-sliding

piston

• For a process in an isobaric

system resulting in volume

change DV, work is: W = -pDV

• First law gives: DU = Q - pDV

• Define enthalpy H = U + pV

Isobaric

closed

system

Q

• DH = DU + D(pV), so:

• DH = Q for the isobaric process

• DU = Q for an isochoric process

If no non-pV work

12

Advanced Thermodynamics

Shaft Work: Steady-Open System

Shaft work Ws

Stationary Open system

1

2

p1

Heat Q

-

W p1V1 - p2V2 Ws -

⇒ Ws - p1V1 p2V2

p2

Flow Device

V2

V1

V2

V1

Moving Closed system

p dV

p dV

Ws

p2

p1

V dp

13

Advanced Thermodynamics

First Law for a Steady-Open System

Shaft work Ws

1

p1

Stationary Open system

2

Flow Device

Heat Q

p2

Moving Closed system

DU Q W

Q Ws p1V1 - p2V2

Q Ws - D( pV )

hence

DH Q Ws

14

Advanced Thermodynamics

Reversible and Irreversible Processes

• Reversible Process: one that can be

made to retrace its path exactly leaving

both system and surroundings

indistinguishable (or at most infinitesimally

different).

• Irreversible Process: one that is not

reversible.

15

Advanced Thermodynamics

Example: An Irreversible Cycle

m

m

A

m

A

A

m

B

m

B

p1

V1

m

B

p2

V2

p1

V1

16

Advanced Thermodynamics

Work for Irreversible Compression

W -

V2

V1

pext dV

Compressions with Tfinal = Tinitial

(a)

pext,2

(c)

(b)

pext,2

pext,2

pext

pext

pext

pext,1

pext,1

V2

V1

V

pext,1

V2

V1

V

V2

V1

V

17

Advanced Thermodynamics

Work for Irreversible Compression

Conclude that:

•

If the piston-cylinder assembly is part of a

compressor, the mechanical power requirement

will be lowest if the process operates reversibly;

and

•

If the piston-cylinder assembly is part of an

engine, we will get more useful work from the

engine if we can operate it reversibly.

18

Advanced Thermodynamics

Reversible Compression

What are the criteria for a compression/expansion

to be reversible?

•

External pressure pext = p throughout the

process

•

No friction

•

Process slow compared with time to re-establish

full thermodynamic equilibrium

19

Advanced Thermodynamics

The Second Law

It is observed that all heat engines have efficiency less than

unity and that all refrigerators require work input. These

observations (and others) are consistent with the second law:

“It is impossible to construct a machine operating in a cyclic

manner whose sole effect is to absorb heat from its

surroundings and convert it into an equivalent amount of

work.” (Kelvin/Planck)

“It is impossible to construct a machine operating in a cyclic

manner which can convey heat from one reservoir at a lower

temperature to one at a higher temperature and produce no

effect on any other part of the surroundings.” (Clausius).

20

Advanced Thermodynamics

The Second Law

The second law can be summarised mathematically by

means of the fundamental equation:

dU = TdS – pdV

and the fundamental inequality:

DSad 0.

(adiabatic process)

Together these are equivalent to the statements of the

second law attributed to Kelvin, Planck and Clausius. Thus

they may be used to show that:

d Qrev

DS

T

h

Thigh - Tlow

Thigh

21

Advanced Thermodynamics

Work of Compression/Expansion

General:

Dh q w s

Reversible:

w s vdp

Isentropic:

w s vdp and Ds 0

Isentropic perfect gas:

and hence

pv C

ws { p2v 2 - p1v1} /( - 1)

cp (T2 - T1)

And various

other forms

Isothermal perfect gas: ws RT ln(p2 / p1)

and

q T (s2 - s1) -RT ln(p2 / p1)

22

Advanced Thermodynamics

Non-Simple Thermodynamic Paths

•

Often we illustrate thermodynamic theory by consideration of

simple thermodynamic paths such as isothermal, isobaric,

isentropic etc.

•

Real processes follow more complicated paths and we need

to model these somehow.

•

Two approaches are commonly used:

For reversible processes assume an approximate

analytical formula which fits the initial and final conditions

– this is called a “polytropic path”.

For irreversible processes start with either adiabatic or

isothermal reversible ideals and apply “efficiency factors”.

23

Advanced Thermodynamics

Thermodynamic Efficiency

•

Irreversible processes cannot be represented by a path

because state variables are not known during the process.

•

In this case, start with an ideal isentropic or isothermal

process connecting p1, T1 and, say, p2.

•

Then define an efficiency factor which relates the actual

work to the work for the ideal reversible adiabatic or

isothermal process as follows.

Adiabatic compressor:

hs = (reversible work)/(actual work)

Adiabatic turbine:

hs = (actual work)/(reversible work)

Isothermal compressor:

hT = (reversible work)/(actual work)

24

Advanced Thermodynamics

Irreversible Adiabatic Paths

Expansion

Compression

h2

h2s

T

p2

p1

p1

h2

h1

p2

T h

2s

h1

S

S

25

Advanced Thermodynamics

Availability (Exergy)

•

•

•

•

In the preliminary design stage of a process, often want to know:

• What is the least work required to bring about a specified

outcome?

• What is the most work that can be extracted from a process

fluid?

Both questions amount to: what is the minimum W.

For some cyclic processes, comparison with Carnot’s cycle is

helpful: e.g. h for a power cycle

In other cases, the concept of availability or, for steady-open

systems, stream availability is more helpful.

26

Advanced Thermodynamics

Availability in a Steady-Open System

•

First law gives: H0 – H1 = Q + Ws

•

Second law gives: S0 – S1 Q/T0

•

Hence: Ws (H0 – T0S0) - (H1 – T0S1)

•

Define stream availability B as

B = (H1 – T0S1) - (H0 – T0S0)

•

Hence Ws -B

or ws -b.

•

Ws = -B if the process is

reversible.

p0, T0

p1, T1

27

Advanced Thermodynamics

Example

What is the maximum work obtainable from N2 in a steady

flow process starting at 200 K and 50 bar, with ambient

conditions at 300 K and 1 bar?

Use thermodynamic tables for the properties of nitrogen:

h1 = 182.38 kJkg-1

h0 = 311.20 kJkg-1

s1 = 5.169 kJK-1kg-1

s0 = 6.846 kJK-1kg-1

b (h1 - h0 ) - T0 (s1 - s0 ) 374.28 kJ kg-1

Hence gas can deliver up to 374.28 kJkg-1 work output.

28

Advanced Thermodynamics

Key Results

Reversible Work

(closed system)

Reversible Work

v2

w - pdv

v1

p2

(steady-open system)

ws vdp

First Law

Du q w

p1

(closed system)

First Law

(steady-open system)

Second Law

Stream availability

Dh q w s

du = Tds – pdv

Dsad 0

b = (h1 – T0s1) - (h0 – T0s0)

29

Advanced Thermodynamics

The Fundamental Equation

CLOSED system, surrounded by reservoir at

(Tres, Pres). Combine 1st & 2nd Laws:

DU Q W

Q Tres DS

DU Tres DS - Pres DV

Restrict to

PDV work

For system undergoing infinitesimal change:

dU TdS - PdV

For system undergoing reversible process:

dU TdS - PdV

30

Advanced Thermodynamics

The Thermodynamic Potentials

Four functions that each contain all the

thermodynamic information about a system:

Internal Energy

Enthalpy

Helmholtz Energy

(symbol F sometimes used)

Gibbs Energy

U

H U PV

A U - TS

G H - TS

Also known as

“free energies” or

“work functions”

Each contains same information, but in different

forms – choose the one that’s convenient

31

Advanced Thermodynamics

Independent Variables

Consider the form of the Fundamental Equation

U

U

dU

dS

dV

dU TdS - PdV

S V

V S

This implies that: (1) S & V are the independent variables

for U and (2) T & P are the first partial derivatives of U

U U ( S ,V )

U

T

S V

U

P -

V S

We can consider U for a system at equilibrium as a surface and

its thermodynamic properties as the slopes, curvatures, etc. of

that surface; analogous results for H, A, G

33

Potentials & Equilibrium

Advanced Thermodynamics

Fundamental eqn, keeping 2nd law inequality: dU TdS - PdV

For a process at constant S & V:

dU S ,V 0

At Equilibrium

dU S ,V 0

Similarly:

dH S , P 0

dAT ,V 0

dGT ,P 0

dH S , P 0

dAT ,V 0

dGT ,P 0

An equilibrium

state is a local

minimum of the

potential along

a specified path

These equations characterise what equilibrium is!

They establish requirements for phase equilibria & stability

35

Advanced Thermodynamics

Equilibrium Requirements

Consider 2 parts, & , of an isolated system

At equilibrium:

dU S ,V 0

dU T

dS

( )

( )

dS

( )

dS

( )

- P dV

( )

0

isolated system No heat

transfer

const. S

const. V

No work

done

( )

T

( )

dV

dS

( )

( )

( )

- P dV

dV

( )

( )

0

0

Eliminating dS() & dV():

dU (T

( )

-T

( )

)dS

( )

- ( P ( ) - P ( ) )dV ( ) 0

T ( ) T ( )

Eqbm

requires: P ( ) P ( )

36

Advanced Thermodynamics

The Chemical Potential

From Calculus, the total differential becomes

N

U

U

U

dU

dS

dV

S V ,ni

V S ,ni

i 1 ni

U

U

U

T

P -

i

S V ,ni

V S ,ni

ni

dni

S ,V ,n j

S ,V ,n j

Extensive properties

N

dU TdS - PdV i dni

i 1

Fundamental Eqn

for Open Systems

Intensive properties

38

Advanced Thermodynamics

Phase Equilibrium Requirements

1 component, 2 phase system:

Eqbm requires:

T

( )

T

( )

P

( )

P

( )

( ) ( )

N component, vapour-liquid system:

vapour

(open system)

N component

isolated system

(V )

i( L) i(V )

…

liquid

(open system)

The extra N

equations needed to

solve the standard

flash problem

T T

P( L ) P(V )

1( L ) 1(V )

( L)

…

mass transfer

Eqbm requires:

N( L) N(V )

Eqns for an N component, -phase system?

41

Advanced Thermodynamics

Phase Behaviour and Phase Diagrams

Some slides courtesy of professor Andrew Haslam and

professor Martin Trusler-ICL

42

Advanced Thermodynamics

What is a “Phase”?

A phase is a homogenous region in space where the

intensive properties are the same. i.e. uniform properties.

A heterogeneous system is made up of two or more phases

(homogenous systems).

Gibbs phase rule links the number of independent

properties (e.g. T, p, composition, …) required to completely

specify a mixture at phase equilibrium

F C 2-

Number of independent

properties specified

(degrees of freedom)

Number of phases at

equilibrium

Number of components in

mixture (pure substance = 1)

43

Advanced Thermodynamics

p-T Projection of Phase Diagram

1000

1000

100

S+L

100

Solid-Liquid (Melting) Curve

Critical Point

10

Critical Point

L

S

1

p /MPa

p /MPa

10

Vapour-Liquid (Boiling) Curve

0.1

Triple Point

0.01

L

1

S

0.1

G

G

L+G

Three-Phase Line

0.01

S+G

Vapour-Solid (Sublimation) Curve

0.001

50

100

150

200

T /K

250

300

0.001

0.01

0.1

1

10

100

v /(dm3/mol)

Point to note: Methane used as example; Lines separate phases; p-T

projection of phase boundaries; semi-log scale1 MPa = 10 bar; Triplepoint tie line; Contracts on freezing; log-log scale for p-v diagram

44

Advanced Thermodynamics

p-T Projection with Isochores and Isotherms

185 K

3

3

L

G

1 mol/dm3

2

4

p /MPa

p /MPa

5

2 mol/dm

S

190.564 K

300 K

200 K

5 mol/dm3

4

3

6

15 10

150 K

3

G

L+G

S+L

5

20 mol/dm

25 mol/dm

3

6

L

2

1

1

0

0

0

75

100 125 150 175 200 225 250 275 300

T /K

5

10

15

20

25

30

3

r/(mol/dm )

• Points to note: Can read off p, r, T values; Methane again on linear

axes; Isochores nearly linear; Sublimation curve too low in pressure

to see on this scaleTie lines; Critical point

45

T-r Projection with Isobars

200

10

4.4992 MPa

10 MPa

3 MPa

180

Advanced Thermodynamics

Two-phase mixture, quality x :

v = (1-x )v l + xv g

Saturated liquid:

v = vl

100 MPa

G

Saturated vapour:

v = vg

p /MPa

T /K

160

1 MPa

1

140

L+G

L

L

S+L

120

0.01

0.1 MPa

S

0.1

0.01

100

0

5

10

L+G

15

20

3

r/(mol/dm )

25

30

35

G

0.1

0.1

0.5

0.9

1

10

3

v /(dm /mol)

Points to note: Can read off p, r, T values; Methane again on

linear axes; Two-phase L+G region; Tie lines; Critical point

46

Advanced Thermodynamics

T-s and p-h Charts

300

4

0.1 MPa

S

L

L+G

G

200 K

p /MPa

T /K

4.4992 MPa

200

190.564 K

300 K

250

1 MPa

185 K

5

10 MPa

120 K

100 MPa

150 K

6

3

2

S

L

L+G

G

150

1

100

-120

0

-100

-80

-60

-1

-40

-1

s /(J K mol )

-20

0

-18

-16

-14

-12

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

h /(kJ mol-1)

Points to note: Very useful for analysis of cycles; Isobars shown;

Typically also plot lines for constant h, v and quality; Methane

used here as example; Reference state: T = 298.15 K, p =

1.01325 bar;

47

T- S diagram for water

100

50

20

5

10

2

0.5

1

0.1

0.2

0.05

4000

200

700

500

Reference state:

s /(kJ·K-1·kg-1) = 0 and u /(kJ·kg-1) = 0

for saturated liquid at the triple point

0.02

T -s Diagram for Water

0.01

1000

800

Advanced Thermodynamics

0.01

0.02

0.05

0.

0.

0.

1

2

5

10

20

50

600

3800

100

p /bar

h /(kJ·kg-1)

v /(m3·kg-1)

Quality

3600

2400

500

T /C

2200

3400

2000

1800

400

1600

3200

1400

300

1200

3000

1000

200

800

2800

600

0.2

100

0.4

0.6

0.8

400

2600

200

0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0

12.0

s /(kJK kg )

-1

-1

48

Advanced Thermodynamics

1.66

1.62

1.58

1.54

1.50

1.46

1.42

1.38

1.34

1.30

1.26

1.22

1.18

1.14

1.10

1.06

1.02

0.98

0.94

0.86

0.90

0.82

0.74

100

0.78

P-h Diagram for R134a

120

p -h Diagram for R134a

0.002

1.70

1.74

1.78

110

Reference state:

h /(kJ·kg-1) = 200 and s /(kJ·K-1·kg-1) = 1.00

for saturated liquid at T = 0°C.

0.005

1.82

100

1.86

90

80

0.01

1.90

70

10

T /°C

-1

-1

s /(kJ·K ·kg )

3

-1

v /(m ·kg )

Quality

1.94

60

50

0.02

1.98

40

30

2.02

20

2.06 0.05

10

p /bar

2.10

0

0.1

2.14

-10

2.18 0.2

-20

-30

1

2.22

-40

2.26

-50

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

2.30

0.9

0.5

1

0.1

100

200

300

150

130

140

120

110

100

90

70

80

60

40

50

30

20

0

400

10

-50

-40

-30

-20

-10

2.34

500

-1

h /(kJ·kg )

49

Advanced Thermodynamics

The p-T phase diagram of a pure substance

• For C = 1 and P = 1: F = 2

– At most 2 intensive variables need to

be specified in a pure-component

(unary) system to define fully its

thermodynamic properties and state

• For C = 1 and P = 2: F = 1

– The two-phase boundaries are fully

specified with one variable

• (recall Clausius-Clapeyron)

• For C = 1 and P = 3: F = 0

t

– At most three phases can be found at

coexistence in a pure-component

(unary) system

• (note, this is not the same as saying

that there can only be one triple point)

50

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

critical curve

(locus of V-L

critical points)

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

51

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

critical curve

(locus of V-L

critical points)

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

xC2 = xC2,1 (say);

(low xC2, high xC1)

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

52

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

critical curve

(locus of V-L

critical points)

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

xC2,2 > xC2,1

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

53

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

critical curve

(locus of V-L

critical points)

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

NB: the V-L critical point does not

(in general) lie at the maximum of a

constant-composition p-T curve.

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

54

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

xC2,3 > xC2,2

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

55

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

xC2,4 > xC2,3

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

56

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

xC2,5 > xC2,4

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

57

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

xC2,6 > xC2,5;

(high xC2, low xC1)

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

58

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Start with p-T projection

The location of the V-L critical point

on a constant-composition p-T

curve “rotates” in clockwise fashion

with increasing composition of the

heavier component.

59

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Increasing xC2, from left to right

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C1

vapour-pressure

curve of pure C2

60

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Phase envelopes are bounded

by the pure-component

vapour-pressure curve for

component A (here C1) on the

left, and that for B (here C2)

on the right.

• One component dominant

relatively “narrow-boiling” systems

narrow boiling

narrow boiling

wide boiling

• Both components present in

comparable amounts “wide-boiling” systems.

61

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

• Range of temperature of the

critical-point locus is bounded

by the critical temperatures of

the pure components.

– no binary mixture has a critical

temperature either below the lightest

component’s critical temperature or

above the heaviest component’s

critical temperature.

• NB: this is not true for critical

pressures.

– A mixture’s critical pressure can be higher than the critical pressures of both

pure components

• e.g., the concave shape for the critical locus.

62

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-composition p-T isopleths

dew

• NB: there are no tie lines on

constant-composition p-T

diagrams

– two points in coexistence share

the same p and the same T but

not the same composition

– constant-x diagrams are not the

most helpful for judging points

in coexistence

bubble

dew

bubble

two (superimposed)

points at coexistence

– intersection of bubble curve at one composition with dew curve at another

composition represents two points at coexistence

• perpendicular to the plane of the diagram

63

Advanced Thermodynamics

Binary mixture: critical locus

• In general, the more dissimilar

the two substances, the

farther the upward reach of the

critical locus.

– When the substances making up the

mixture are similar in molecular

complexity, the shape of the critical

locus flattens down.

from: J.W. Amyx, D.M. Bass, R.L. Whiting,

Petroleum Reservoir Engineering, McGraw Hill, 1960

64

Advanced Thermodynamics

Types of fluid phase behaviour in binary mixtures

• Classification of van Konynenburg and Scott

– Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London A 298 (1980) 495–540

Type I

Type II

Type III

p

U

A

B

A

U

B

Type IV

U

L

B

Type V

U

A

A

Type VI

U

B

A

L

B

U

A

L

B

T

65

Advanced Thermodynamics

Types of fluid phase behaviour in binary mixtures

• Classification of van Konynenburg and Scott

– Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London A 298 (1980) 495–540

Type I

Type II

Type III

p

U

A

B

A

U

V

Type IV

U

L

B

Type V

U

A

A

Type VI

U

B

A

L

B

U

A

L

B

T

66

Advanced Thermodynamics

Types of fluid phase behaviour in binary mixtures

• Classification of van Konynenburg and Scott

– Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London A 298 (1980) 495–540

Type I

Type I

p

• Two substances of similar chemical type

U

- e.g., CH4 + N2; CO2 + O2; alkane + “similarsized” alkane

A U ◦ CH4 + up to n-C

A 5H12 is type I; CH4 + n-C6H14

B

B

is typeV V

◦ C2H6Type

+ up Vto n-C18H38 is typeType

I; C2VI

H6 + up to

Type IV

n-C19H40 is type V

U

U

A

A

II discussed so farType III

• What we’veType

mostly

U

L

B

A

L

B

U

A

L

B

T

67

Advanced Thermodynamics

Types of fluid phase behaviour in binary mixtures

• Classification of van Konynenburg and Scott

– Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London A 298 (1980) 495–540

Type I

Type II

Type III

p

U

A

Type II

B

Type IV

A

U

V

Type V

A

B

Type VI

• L-L immiscibility

at T < Tc of the more-volatile

component

U

U

- e.g., CO2 + alkanes up to n-C12H26

• Type I can be thought of as “Type II, but where L-L immiscibility

is

U

A masked

L by the

A L

A

B solid phase”

B

B

U

L

◦ i.e., the L-L boundary lies at lower temperature than the

T

freezing temperature

68

Advanced Thermodynamics

Types of fluid phase behaviour in binary mixtures

• Classification of van Konynenburg and Scott

– Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. London A 298 (1980) 495–540

Type I

Type II

Type III

p

U

A

Type III

B

Type IV

A

U

V

Type V

A

B

Type VI

U

U is large enough, L-L region persists to

• If mutual immiscibility

of two substances

higher T, and Type II Type III

- locus of L-L critical points merges with V-L critical curve

U

L

A n-C

L 13H28; methane

- Ae.g.,

from

+Asqualane; many

B

B

B alkane +

U CO2 + alkanes

L

polar-molecule mixtures; many hydrocarbon + water mixtures (including,

T

low-MW alkane + water)

69

Advanced Thermodynamics

Types of fluid phase Type

behaviour

in binary mixtures

V

•

• Instead of ending at the V-L critical point of the

more-volatile

component (as and

in TypeScott

I), the critical

Classification of van

Konynenburg

at the V-L critical point of the less– Phil. Trans. Royal Soc. Londoncurve

A 298beginning

(1980) 495–540

volatile component ends at a lower-critical end point

(LCEP) connected

Type I

Type II to a L-L-V three-phase

Type IIIline.

- e.g., some alkane + alkane mixtures

p

U

◦ CH4 + n-C6H14; CH4 + 2-methylpentane;

CH4

+ 3-methylpentane; CH4 + 2,3dimethylbutane; …

A

A U ◦ C H + up to n-C

A H

B

2 6 V

19 40

B

Type IV

Type V

U

A

U

L

Type VI

U

B

A

L

B

U

A

L

B

T

70

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-x p-T slices and retrograde behaviour

• Constant-temperature path: retrograde behaviour

– liquid evaporates to vapour upon an increase in pressure

• (or vapour condenses to liquid upon a decrease in pressure)

V L+V V L

V L+V V L

V L L+V L

L

L

L+V

L

L+V

L+V

V

V

V

• The evaporation of liquid by an increase in pressure ((a) and (b) here) was termed

retrograde condensation by J. P. Kuenen in 1892

− retrograde: “the order of something reversed”

71

Advanced Thermodynamics

Constant-x p-T slices and retrograde behaviour

• Constant-pressure path: retrograde behaviour

– vapour condenses to liquid upon an increase in temperature

• (or liquid evaporates to vapour upon a decrease in temperature)

L V L+V V

L L+V L V

L L+V L V

L

L

L+V

L

L+V

L+V

V

V

V

A: cricondendbar (or maxcondendbar); B: cricondendtherm (or maxcondendtherm)

72

Advanced Thermodynamics

Phase Envelopes for Reservoir Fluids

Production

pathway

Reservoir

depletion

Phase envelope

completely determined by

(Tsep, Psep)

composition. Why?

Dry gas

Wet gas

GOR, [m3/m3]

no liquid

> 2500

C7+, [mol%]

< 0.7

0.7-4

Retrograde

Volatile oil

Black oil

600 to 2500

300 to 600

< 300

4-12.5

12.5 to 20

> 20

condensate

73

Advanced Thermodynamics

Issues for Engineers

•

•

•

•

•

•

Evaluate reserves & production strategy

Facilities Sizing

Gas-Oil Ratio – GOR & CGR

Condensate drop-out and Gas Recycling

Pipeline specifications: – HC dew point

Location of dew point curve VERY

sensitive to (small) amounts of heavy HCs

– Dew points key parameter for measurement

74