Are protectionist policies harmful for developing countries?

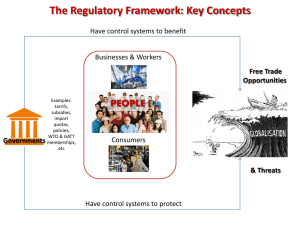

advertisement

School of Oriental and African Studies International Foundation Courses and English Language Studies FOUNDATION DIPLOMA FOR POSTGRADUATE STUDIES Issues in International Development Studies Term 3 Assignment, May 2019 Critically analyse the claim of neoliberals that protectionist trade policies are harmful for developing countries. Submitted by Michael Koenig FDPS No. 666027 Word count: 2172 2 The statesman who should attempt to direct private people in what manner they ought to employ their capitals, would not only load himself with a most unnecessary attention, but assume an authority which could safely be trusted, not only to no single person, but to no council or senate whatever, and which would nowhere be so dangerous as in the hands of a man who had folly and presumption enough to fancy himself fit to exercise it. Adam Smith, 1776 (Smith, 2012, p. 446) Protectionist trade policies have been the topic of fervent debates since the 18th century. With a relentless trade war currently raging between the United States and China (BBC, 2019) and one with Mexico lingering in the air (Casselman, 2019), the question whether a state should protect domestic industries by imposing tariffs and quotas on imports is more relevant than ever. Not only has WTO Director-General Roberto Azevedo talked about the ‘worst crisis in global trade since 1947’ referring to the tit for tat of U.S. import tariffs and Chinese retaliations (cited in Gallas, 2018), but analysts have also warned of potentially massive economic damage on a worldwide scale (BBC, 2019). Whilst the Trump Administration continuously emphasises its determination to restore the “greatness” of the Reagan years, a time indeed characterised by neo-liberal trade policies, President Trump is actually promoting protectionism in favour of special-interest groups at a large scale (Stiglitz, 2017). It was, however, not long before Ronald Reagan took office when the classic neo-liberal critique of protectionism originated at the University of Chicago’s Department of Economics, paving the way for Reaganomics, of which Nobel-laureate economist Milton Friedman became the most prominent and popularised advocate (Emmett, 2010). Neo-liberals to this day claim that protectionism damages the economy and causes superfluous customer spending; they dismiss protectionism as having been unsuccessful and disruptive in the past, and they highlight that corruption and bias are the inevitable outcomes whenever states are tampering with the market. Using examples from developing countries, I will discuss these aspects in turn, arguing that even though the neo-liberal objections against protectionism are 3 striking and convincing, both neo-liberalism, as well as protectionism, suffer from the same moral defects. Thus, defects undermine the validity of both systems and, inevitably, lead to the wish for an alternative and less corrupt economic system. But what is the theoretical underpinning of protectionism, why has it been adopted by developing economies and how has it been criticised by neo-liberals? Any development theory until the end of the 20th century believed in industrialisation as a prerequisite for economic growth, since manufactured goods, having the highest price elasticity, usually allow for the highest gains and, thus, for an increase in investment (Desai and Potter, 2002; Parkin, 2014). At the same time, however, some countries can produce the same good or prime commodity cheaper than others. Countries with better capability of production are said to have comparative advantage, and it is an economic rule that an import from a country with comparative advantage is more profitable than manufacturing the same good domestically due to a decrease of the price, as Figure 1 shows. Figure 1, The effects of comparative advantage (Source: Parkin, 2014, p. 153) In the case of many developing countries, however, comparative advantage usually exists only for prime commodities or cheap manufactured goods with little price elasticity. As a 4 consequence, a country can either accept export dependency on those products until it reaches the so-called ‘take-off stage’ of industrial development (Rostow, 1979), or it can be protectionist and counteract the ‘invisible hand of the market’ (Adam Smith) by imposing tariffs and quota in order to prevent customers from purchasing imported goods (Dutt, 2009) and, thus, achieving ‘manufactured commodity self-sufficiency through import substitution’ (Todaro and Smith, 2011, p. 595). However, drawing heavily on ideas already expressed by Adam Smith in his seminal 1776 publication The Wealth of Nations (Smith, 2012), neo-liberals argue that protectionism has a damaging effect on the economy. They say that it not only causes an increase in consumer price, but it also reduces the quantity of products sold. Moreover, it generates a deadweight loss, resulting in less private capital being available for further investment (see Figure 2). Figure 2, Free trade and trade with tariffs (Source: Parkin, 2014, p. 154) In order to support their criticism, neo-liberals use empiric evidence from unsuccessful import-substitution industrialisation (ISI), notably referring to examples from Latin America (Clarke, 2002; Desai and Potter, 2002; Clark, 2007; Silva, 2007; Todaro and Smith, 2011). On one hand, they point out that in most instances, states financed ISI through massive loans from foreign banks, ultimately leading to devastating debt crises such as in Mexico and Brazil 5 in the early 1980s (Thirlwall, 2007); on the other hand, they stress that protectionist policies, no matter how admirable their cause, inevitably nurtures corruption and the influence of special-interest groups, since no politician or government official is immune from being led by self-interest (Friedman, 2002). They warn that ‘one of the great mistakes is to judge policies and programs by their intentions rather than their results’ (Friedman cited in Heffner, 1975). Besides these economic reasons, neo-liberals also see their rejection of protectionism as an almost sacred obligation for reasons deeply rooted in history and politics (Friedman, 2002). Based on Hayek’s 1944 polemic The Road to Serfdom (Hayek, 2005), they believe that in order to control the economy, a state would have to curtail individual freedom; they say that no agreement can ever be achieved in a state regarding the direction of economic planning; out of frustration over division and disruption, calls will be heard for a powerful, strong man to pave the way into an allegedly more orderly and prosperous future, at the price of a complete surrender of freedom. As a moral deterrent to this scenario, Hayek (1994, p. 49) cites Mussolini: ‘The more complicated the forms assumed by civilisation, the more restricted the freedom of the individual must become.’ Thus, neo-liberals implicitly link the prevention of totalitarianism with the fight for free-market capitalism. And this indeed happened not only with immense military power in the Second World War but also, through the soft power of Structural Adjustment Programmes (SAPs), in the 1980s and 1990s: the World Bank and IMF demanded from their aid receivers the introduction of free markets and democratic government as conditionalities for development aid (Mason and Asher, 1973; Rist, 2002). Despite all the neo-liberal criticism of protectionist trade policies, there seems to be little choice for LDCs than to adopt ISI in order to stimulate their development. Due to limited price elasticity of their most common source of income, prime commodities, investment is generally limited to resource exploitation, often even under the control of foreign 6 corporations, which causes an additional outflow of money (World Bank, 1998; Khan, 2007; Dutt, 2009). Moreover, prices for primary products tend to fall gradually over the years, a phenomenon first described as the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis (Todaro and Smith, 2011) and subsequently proven by a number of empirical studies, such as Harvey et al. (2010), data of which is shown in Figure 3. The result of this downward trend is a deterioration of commodity terms of trade and an impediment of growth, factors that might justify the adoption of ISI despite its weaknesses. Figure 3, Empirical data in support of the Prebisch-Singer hypothesis (Source: Harvey et al., 2010) When ISI is adopted, however, it appears to have equally positive effects on growth than a neo-liberal development strategy. Figure 4 juxtaposes two extremes: Hong Kong, Friedman’s prime example for a successful Smithian free-market economy (Monnery, 2017), and Chile, a famously unsuccessful example of ISI (Silva, 2007). Note that the comparison is only valid 7 until the early 1980s, the time when the Latin American debt crisis struck Chile and the economy went into recess. Subsequently, both countries were using a neo-liberal model, the effects of which are also visible in the graph. A similar trend can be seen in Figure 5, which compares the GDP per capita of several regions of the globe. Figure 4: GDP Hong Kong, Chile and Zambia Figure 5: GDP per capita of world regions (Source: https://data.worldbank.org, accessed 26 May 2019) (Source: https://data.worldbank.org, accessed 26 May 2019) Unfortunately, the neo-liberal objection against protectionism regarding bias and corruption has to be sustained, as the following examples clearly demonstrate. Firstly, a number of studies show serious corruption in developing countries (World Bank, 1998; Khan, 2007; Dutt, 2009), affirming that self-interest all too often the driver for political decisions and economic bearings. Moyo (2009), for instance, mentions Mobutu Sese Seko, who alone illegitimately acquired over US$5 billion between 1965 and 1997. Secondly, in copper-rich Zambia, ISI has been applied heavily since the country’s independence in 1964, but the GDP did not rise until the mid-2000 (see Figure 4); however, Seidman (1974) shows that in fact the planning of ISI was largely shaped in favour of special-interest groups and a wealthy elite. An assembly plant of Italian car manufacturer FIAT, for instance, was highly subsidised by the government, but this investment was only geared towards high-end consumers, whilst the goods most needed, such as tools for agricultural production, were neglected. 8 In recent years, attempts have been made (Chang, 2007, 2010; Klein, 2007) to dismiss neoliberal reservations against protectionism with an ad hominem (Weston, 2009) argumentation, attempting to discredit neo-liberal economists by showing fallacies in their claims or bad intentions behind their good-looking recommendations. This is to say that Chang speaks of neo-liberal intentions to make the public belief that AIEs rose through free-market capitalism, whilst in fact all these countries had adopted protectionism. He then concludes that through SAPs, neo-liberals decline LDCs the kind of development AIEs had experienced in the past. Not only, though, do neo-liberals frequently point towards protectionism as the main driver of U.S. development over decades (Friedman, 2002), but they also complain about an overregulation of the U.S. economy and an explosion of the U.S. administration (Heffner, 1975). Furthermore, Pennington (2011) points out that Chang not only lacks historical accuracy and thorough use of source material to support his claims, but he also tends to create ‘caricatures’ of his opponents. Similarly, Klein (2007) evokes the malevolent use of economic shocks to implement policies and regulations for the benefit of a selected few, whilst Norberg (2008) is eager to reject most of Klein’s accusations by proving the inaccuracy of historical data presented by her. There seems to be, however, one serious argument that indeed needs to be taken into account against the impression that protectionism is always coercive, as well as ‘oppressive and tyrannical’ (Smith cited in Stewart, 1829, p. 324), whilst neo-liberalism, due to its noble support of freedom and democracy, claims to represent moral authority. Nevertheless, several authors have suggested that neo-liberal SAPs have been simply coerced upon LDCs by connecting them with aid (Chambers, 2005; Acemoglu and Robinson, 2013; Pilger, 2016). Furthermore, Moyo (2009) points out that foreign aid, usually connected with a neo-liberal agenda, is the main fuel for corruption in Africa. Finally, it has been said that through globalisation, being a long-term effect of the neo-liberal policies of the 1980s, world 9 dominance has shifted to big corporations (Korten, 2001; Stiglitz, 2017), thus subverting the original ideas of little corporate influence in neo-liberalism (Friedman, 2002). In the words of Foster (2006, p. 40), this means: ‘Now we are told that this invisible hand has been globalized to such an extent that the sovereign power of nation states over their territorial domains themselves has been vastly diminished.’ Finally, it can be concluded that both protectionism, as well as neo-liberalism, suffer from a disparity between theory and practice (Todaro and Smith, 2011). Both approaches have clear values, although the neo-liberal criticism of protectionist trade policies is undermined by its own shortcomings. Not only does the situation facilitate the wish for an alternative economic system, as Korten (2001), Chambers (2005) and Stiglitz (2017) have suggested, but the fact that the main shortcomings of both neo-liberalism and protectionism are located in the area of self-interest and greed raises the question whether or not a more moral strain in the economy could be conceived, as Taylor (2014) hopes. Such approach would not only require further research, but it would also be in full alignment with Adam Smith, the patriarch of neoliberalism, who saw great value in a refined, elevated and compassionate attitude towards society: ‘to restrain our selfish, and to indulge our benevolent affections, constitutes the perfection of human nature’ (Smith, 1982, p. 25). 10 Bibliography Acemoglu, D. and Robinson, J. A. (2013) Why nations fail: the origins of power, prosperity, and poverty. London: Profile Books. BBC (2019) ‘US-China trade war in 300 words’, 14 May. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-45899310 (Accessed: 27 May 2019). Casselman, B. (2019) ‘As Trade War Spreads to Mexico, Companies Lose a Safe Harbor’, The New York Times, 2 June. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/01/business/economy/trump-trade-tariffs-mexico-cost.html (Accessed: 2 June 2019). Chambers, R. (2005) Ideas for development. London; Sterling, VA: Earthscan. Chang, H. (2007) Kicking away the ladder: development strategy in historical perspective. Reprinted. London: Anthem (Anthem world economics). Chang, H.-J. (2010) 23 things they don’t tell you about capitalism. London: New York : Allen Lane. Clark, D. (ed.) (2007) The Elgar companion to development studies. Cheltenham: Elgar. Clarke, C. (2002) ‘The Latin American structuralists’, in Desai, V. and Potter, R. B. (eds) The companion to development studies. London : New York: Arnold ; Oxford University Press, pp. 92–96. Desai, V. and Potter, R. B. (eds) (2002) The companion to development studies. London : New York: Arnold ; Oxford University Press. Dutt, P. (2009) ‘Trade Protection and Bureaucratic Corruption: An Empirical Investigation’, The Canadian Journal of Economics / Revue canadienne d’Economique, 42(1), pp. 155–183. Emmett, R. B. (ed.) (2010) The Elgar companion to the Chicago school of economics. Cheltenham, Glos, UK ; Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar. Foster, J. B. (2006) Naked imperialism: the U.S. pursuit of global dominance. Place of publication not identified: Aakar Books. Friedman, M. (2002) Capitalism and freedom. 40th anniversary ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Gallas, D. (2018) WTO chief warns of worst crisis in global trade since 1947 - BBC News. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-46395379 (Accessed: 27 May 2019). Harvey, D. I., Kellard, N. M., Madsen, J. B. and Wohar, M. E. (2010) ‘The Prebisch-Singer Hypothesis: Four Centuries of Evidence’, Review of Economics and Statistics, 92(2), pp. 367– 377. doi: 10.1162/rest.2010.12184. Hayek, F. A. (2005) The road to serfdom: with The intellectuals and socialism. London: Institute of Economic Affairs. Hayek, F. A. von (1994) The road to serfdom. 50th anniversary ed. / with a new introd. by Milton Friedman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Heffner, R. (1975) Living Within Our Means. (Richard Heffner’s Open Mind). Available at: https://www.thirteen.org/openmind-archive/public-affairs/living-within-our-means/ (Accessed: 2 June 2019). Hira, A. (2007) ‘Did ISI fail and is neoliberalism the answer for Latin America? Re-assessing common wisdom regarding economic policies in the region’, Revista de Economia Política, 27(3), pp. 345–356. doi: 10.1590/S0101-31572007000300002. Khan, M. (2007) ‘Rent seeking and corruption’, in Clark, D. (ed.) The Elgar companion to development studies. Cheltenham: Elgar. Klein, N. (2007) The shock doctrine: the rise of disaster capitalism. London: Allen Lane. 11 Korten, D. C. (2001) When corporations rule the world. 2nd ed. San Francisco, Calif. : Bloomfield, Conn: Berrett-Koehler Publishers ; Kumarian Press. Mason, E. S. and Asher, R. E. (1973) The World Bank since Bretton Woods: the origins, policies, operations, and impact of the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the other members of the World Bank group: the International Finance Corporation, the International Development Association [and] the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes. Washington: Brookings Institution. Monnery, N. (2017) Architect of prosperity: Sir John Cowperthwaite and the making of Hong Kong. London: London Publishing Partnership. Moyo, D. (2009) Dead aid: why aid is not working and how there is another way for Africa. London: Allen Lane. Norberg, J. (2008) Defaming Milton Friedman, Cato Institute. Available at: https://www.cato.org/publications/commentary/defaming-milton-friedman (Accessed: 2 June 2019). Parkin, M. (2014) Economics. 2nd Custom Edition for Suffolk University. Boston: Pearson. Pennington, M. (2011) What Ha Joon Chang doesn’t tell you about ‘free market economics’, Institute of Economic Affairs. Available at: https://iea.org.uk/blog/what-ha-joon-changdoesn%E2%80%99t-tell-you-about-%E2%80%98free-market-economics%E2%80%99 (Accessed: 2 June 2019). Pilger, J. (2016) The new rulers of the world. New edition. London ; New York: Verso. Rist, G. (2002) The history of development: from western origins to global faith. New ed., rev. and expanded. London ; New York: Zed Books. Rostow, W. W. (1979) The stages on economic growth: a non-communist manifesto. 2. ed., reprinted. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. Seidman, A. (1974) ‘The Distorted Growth of Import-Substitution Industry: the Zambian Case’, The Journal of Modern African Studies, 12(04), p. 601. doi: 10.1017/S0022278X00014282. Silva, E. (2007) ‘The Import-Substitution Model: Chile in Comparative Perspective’, Latin American Perspectives, 34(3), pp. 67–90. Smith, A. (1982) The theory of moral sentiments. Indianapolis: Liberty Classics (The Glasgow edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith, 1). Smith, A. (2012) The wealth of nations: an inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Ware, Hertfordshire: Wordsworth (Wordsworth classics of world literature). Stewart, D. (1829) The philosophy of the active and moral powers of men. Cambridge: Hilliard and Brown (The Works of Dugald Stewart in seven volumes). Stiglitz, J. E. (2017) Globalization and its discontents revisited: anti-globalization in the era of Trump. Revised edition. London: Penguin Books. Taylor, T. (2014) ‘Economists may prefer to be value neutral, but many critics find fault in the relationship between economics and virtue’, Finance & Development, 51(2), p. 5. Thirlwall, A. P. (2007) ‘Debt crisis’, in Clark, D. (ed.) The Elgar companion to development studies. Cheltenham: Elgar, pp. 102–105. Todaro, M. P. and Smith, S. C. (2011) Economic development. 11. ed. Harlow: Pearson (The Pearson series in economics). Weston, A. (2009) A rulebook for arguments. 4th edition. Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. World Bank (1998) ‘Corruption and development’, Prem Notes, (4). Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/11545/multi_page.pdf?sequ (Accessed: 26 May 2019).