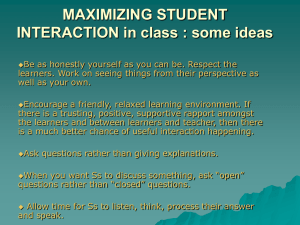

Freie Universität Berlin Zentrum für Lehrerbildung Institut für Englische Philologie Masterarbeit Teacher talk and student talk: Is there a right balance? And how much do teachers really speak? A study on teacher and student talk in an EFL classroom. 29th February 2016 Jakob Hetzelein nasenatmer@posteo.de Contents List of Figures iii List of Tables iv 1. Introduction 1 2. Theoretical framework 2.1. Communication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.2. Communication in the language classroom . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2.3. Types of questions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2 2 3 5 3. Empirical findings on classroom communication 3.1. Teacher and student talking times . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.2. DESI video study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3.3. Kampa’s case study at a Berlin secondary school . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6 6 9 10 4. Teacher talk and student talk: Is there a right balance? 4.1. Pro teacher talk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.1.1. Grammar-Translation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.1.2. Total Physical Response . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.1.3. The Natural Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.2. Pro student talk . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.2.1. Audio-Lingualism . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.2.2. The Silent Way . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.2.3. Communicative Language Teaching . . . . . . . 4.3. Other sources . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3.1. Recommendations by educational authorities . . 4.3.2. Haß: Fachdidaktik Englisch . . . . . . . . . . . . 4.3.3. Grimm, Meyer and Volkmann: Teaching English 4.4. Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12 12 12 13 13 14 14 15 16 17 17 18 18 20 5. Design of the case study 5.1. Aims . . . . . . . . . . . 5.2. Anonymisation . . . . . 5.3. The sample . . . . . . . . 5.3.1. The school . . . . 5.3.2. The students . . . 5.3.3. The teacher . . . 5.3.4. The lessons . . . 5.4. Instruments . . . . . . . 5.4.1. Audio recordings 5.4.2. Questionnaire . . 5.5. Analysis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 21 21 22 22 22 23 23 24 24 26 27 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5.6. Quality criteria . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6. Results 6.1. Talking times . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.2. Question types . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.3. Turns . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6.4. Questionnaire results on teacher talking time 6.5. Questionnaire results on student talking time 6.6. Questionnaire results on overall contentment 7. Discussion 7.1. Teacher talking time . 7.2. Student talking time . 7.3. Silence . . . . . . . . 7.4. Question types . . . . 7.5. Turns . . . . . . . . . 7.6. Contentment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28 28 30 30 31 32 33 . . . . . . 33 33 35 36 37 37 38 8. Conclusion A. Appendix A.1. Questionnaires . . . . . . . . A.2. Additional results . . . . . . A.2.1. Talking times . . . . A.2.2. Question types . . . A.2.3. Turns . . . . . . . . A.2.4. Questionnaire results 27 39 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bibliography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 41 43 43 44 45 45 50 ii List of Figures 1. 2. Seating plan of the class. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Coding example from lesson four. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Appendix 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 23 25 41 Student questionnaire. . . . . . . . . . . Teacher questionnaire. . . . . . . . . . . The teacher’s perceived and desired TTT. The students’ perceived and desired TTT. The teacher’s perceived and desired STT. The students’ perceived and desired STT. iii . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 41 42 46 46 47 47 List of Tables 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Results from empirical studies quoted in Chaudron (1988). . . . . . . . . . . Results from Schönwälder (1988), Hasan (2006), Inamullah et al. (2008), Hitotuzi (2006) and Tsui Bik-May (1985). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Results from Hasan (2006) on question types. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Results from DESI video study (Helmke et al. 2008). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Results from Kampa (2012). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Teacher and student talking times. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Question types asked by the teacher and student initiatives. . . . . . . . . . Allocation of turns. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Perception and desire for TTT and its difference. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Perception and desire for STT and its difference. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Contentment with the lessons. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Appendix 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 7 7 8 9 10 29 30 31 31 32 33 41 Overall student talking times and teacher ranking. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Teacher and student talking times without silence. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Share of active and silent students per lesson. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Question types asked by the teacher, without student initiatives. . . . . . . . Individual turns per lesson and average turn length. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Correlation coefficient between perceived and actually measured talking time. Difference of perception and desire for TTT; grouped values. . . . . . . . . . The students’ perceived and desired TTT; individual values per lesson. . . . Difference of perception and desire for STT; grouped values. . . . . . . . . . The students’ actual, perceived, and desired talking times per lesson. . . . . iv 43 44 44 44 45 45 48 48 49 49 1. Introduction Language learning may be seen as a process which grows out of the interaction between learners, teachers, texts and activities. —Breen and Candlin (2001: 14) The importance of speaking in English language teaching (ELT) methodologies is no longer a point of contention. Audio-Lingualism and Communicative Language Teaching emphasised the centrality of speaking to learning and using languages. Accordingly, teacher training programmes and modern curricula have been shifting the focus from teacher-centred methods towards learner-centredness. As part of this process, teacher talking time is reduced in favour of student talking time. However, the time that is granted for pupils’ speech production in class has been shown to be alarmingly low repeatedly. This is not to say that all educationists and scholars agree upon the necessity to reduce TTT to an absolute minimum, but there is a tendency to acknowledge the importance of learner activation and student talk in the language classroom. In addition, there is no general consensus on an ideal balance that would best serve language learning. How much should teachers talk in class? Is it enough to simply maximise STT to promote language learning? Do students actually want to speak more? And can teachers really reduce their talk? Can learners and teachers correctly assess how much they talk in class? In the following thesis, I am going to answer these questions both theoretically and empirically. In the theoretical part, which is based on an analysis of research findings as well as various teaching approaches and learning theories, I will attempt to answer the title question „Is there a right balance between teacher talk and student talk?”. In the empirical part I will describe a case study I carried out in a Teaching English as a Foreign Language (TEFL) classroom in a Gymnasium in Berlin. Having taped and analysed several English lessons, I have data that allows for a quantitative analysis of classroom talk. I also used a questionnaire to ask the learners and teacher their estimations for talking time and compared these responses to the actual findings. My primary research question is “How much do teachers talk in German EFL classrooms?” but I am of course limited to answer it only with regards to the one teacher studied in this case. Apart from that, I will evaluate and analyse her style of teaching by including the numbers of turns given to students, the types of question asked as well as the methods used. In the course of this paper, I will move from the general to the specific by first defining some important general concepts and describing communication in and outside of the classroom (Section 2). Secondly, I will present previous empirical findings regarding the balance of TTT 1 and STT in the classroom in Section 3. After this, I will answer the title question in Section 4 after consulting the most important language teaching methodologies and approaches, as well as recommendations by educational authorities and TEFL textbooks for their stances on teacher and student talk. In the empirical part of my dissertation, I will first describe the research design, the sample and the instruments in Section 5. In Section 6, I will present the findings and discuss them in Section 7. After summarising what I have done and providing an outlook on future research desiderata I will finish this thesis with a conclusion in Section 8. Before delving into the subject, I need to point out that this study is a replication of a master’s thesis that was submitted to the Zentrum für Lehrerbildung of Freie Universität Berlin by Kampa (2012). The purpose of my study is to compare his findings to a different Berlin classroom at a different type of school and draw conclusions from this comparison. In this project I used the same research method as Kampa did — audio taping the classroom and questionnaires — to allow for better comparability. Yet, due to theoretical differences, my conceptual framework is based on my own research and might therefore differ substantially from his. Therefore, I will only contrast the empirical results of his study with mine. 2. Theoretical framework In order to be clear about the concepts used and the extent of this study, I will define the most important terms first. I will do this by moving from a general concept of communication to its instantiation in the classroom. I will also define the different types of questions used by teachers in the classroom. 2.1. Communication I base my understanding of communication on the model of Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson (1968). In their pragmatic concept, virtually every behaviour qualifies as communication: Thus, from this perspective of pragmatics, all behavior, not only speech, is communication, and all communication—even the communicational clues in an impersonal context—affects behavior. (ibid.: 22) This view is operationalised in the first of their five Axioms of Communication which claims that “one cannot not communicate” (ibid.: 49, original emphasis). This means that any action — be it a bodily gesture or a conversation between two people — is perceived as communication. 2 In axiom two, they classify each message as having two levels, namely “content and relationship” (Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson 1968: 51): content refers to the information that is transferred while relationship defines the relation between the two interactants and could also be termed metacommunication. Crucially, they assume that relationship governs content in that it classifies it, which holds true for classroom communication as well because the relationship level often implies a command such as “Answer this question”. (ibid.: 51-54) The third axiom asserts that communication is “interpunctuated” (ibid.: 59), i.e. that there is a causal relationship between the actions or messages that follow each other. This also applies to classroom communication where the responses from students are caused by the teacher’s questions. In axiom four they distinguish between verbal, in their words “digital” (ibid.: 62) and nonverbal or “analogic” (ibid.: 62) communication. While obviously both kinds of communication play an important role in classroom interaction, teaching methodologies and educationists are mainly concerned with verbal forms of communication. The fifth axiom postulates that there are two different relationships between the communicants: “symmetrical interaction” (ibid.: 68) which signifies an equality of power, and “complementary interaction” (ibid.: 68) which signifies an imbalance of power and dominance between communication partners. Similarly, Edwards and Westgate (1994: 45) differentiate between “talk which has to be organized” because conversation partners share equal rights, and “talk which is organized largely through unequal rights”. They suppose that “instructional conversation” (ibid.: 46), as it is dominant in classroom settings, is always unequal. Therefore, when we look at teacher talk, we only encounter complementary communication, while student talk in small groups can be characterised as symmetrical interaction. 2.2. Communication in the language classroom There are two types of talk that will be investigated in this study: teacher talk and student talk, and they can be aligned with three basic directions of communication in the classroom: teacher-student, student-teacher and student-student communication. In this section, I am going to define these processes and describe how they benefit or inhibit language learning. The first direction, teacher-student communication, refers to teacher talk, describing language output by the teacher which serves as language input for pupils to model their foreign language skills upon. It happens while everybody else in class is supposed to be silent and is measured and presented under the label TTT. 3 The second direction, student-teacher communication denotes one form of student talk, which in turn is important input for the teacher in order to diagnose their1 pupils’ level of language knowledge and competence. Student-teacher communication happens when one learner speaks while the others listen, and is comprised under STT in my study. These two types of discourse were described and analysed in detail by Sinclair and Coulthard in their 1975 book Towards an Analysis of Discourse. According to their study, the most frequently used discourse structure in the classroom was the so called IRF exchange. This exchange consists of three separate elements, the first one being the “Initiation (I)” move, the second one the “Response (R)” move, and the third one the “Feedback (F)” move (Sinclair and Coulthard 1975: 50). It goes without saying, that most of the IRF exchanges are initiated by the teacher. In their typology, nine kinds of exchanges are teacher-initiated while only two types are initiated by pupils, the so called Student Elicit and Student Inform. The most frequent exchanges are Teacher Elicit and Teacher Direct. (ibid.: 50-56) One consequence of these relations is the amount of talking time afforded the teacher and students: if in the vast majority of classroom exchanges the first and the third move are by the teacher, about two thirds of the turns in a lesson are taken by the teacher. While we need to keep in mind that turns have varying lengths, e.g. the feedback move is typically rather short, this basic type of exchange can be seen as a part of the reason why teachers usually talk so much more than their pupils. Additionally, the competence of turn-taking cannot be trained when the teacher controls the interaction, which is why this pattern is criticised for its teacher-centredness (Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann 2015: 238-240). Still, the model provides a useful tool for the analysis of classroom discourse. Finally, the third direction of interaction, student-student communication (henceforth SSC) is the second form of student talk and is highly important in language classrooms, as it is the only form of discourse where pupils talk in a symmetrical setting and do not await constant error correction by their teacher. SSC most frequently happens during pair or group work phases when several pupils are talking simultaneously in their respective groups and are immersed in meaningful interaction. For that reason, I will continue to strictly differentiate between SSC and STT in this study. Classroom communication is also characterised by silence: every lesson has periods of silence, for instance when teachers wait for answers, or students are solving tasks on their 1 Although it is considered to be grammatically wrong by some, I deliberately use the singular they in order to avoid binary gender pronouns. I do not want to reproduce heteronormative gender roles by using gendered language and therefore use this neutral way to refer to a singular person by using a plural pronoun. 4 own. Not all of those silences are essential for language learning and I will include only those that belong to the lesson (as described in Section 5.4.1). At last, I define a turn as an act of speech by a participant who either starts talking by themselves or is nominated by another one. I will use it interchangeably with the word utterance. Due to the nature of SSC phases, it is not possible to ascribe turns to individual students, which is why SSC is only measured for the whole group. 2.3. Types of questions Teachers ask a lot of questions or direct their pupils to do tasks. Therefore it is necessary to differentiate between and define the most frequently asked kinds of questions, namely display questions, referential questions, and reasoning questions. Display questions are usually closed questions for which the teacher knows the answers and which allow the learners to display their knowledge. They are the most frequent kind of question asked not only in language classrooms (Thornbury 1996: 281). Notably, display questions elicit rather short answers and inhibit sustained interaction (Hasan 2006: 8). The prevalence of display questions in the classroom marks an important difference to everyday discourse, where the majority of questions asked are of a different kind: referential questions. Referential questions are those to which the asking person does not know the answer yet, which is why Thornbury (1996: 281) refers to them as “genuine questions”. Several researchers agree that they require a higher cognitive effort not only on the side of the responder, but especially the person who asks (ibid.: 281-282). This might be the reason why they are so infrequent in the classroom. The third kind are reasoning questions, i.e. those questions that ask pupils for their personal opinion so that there is no right or wrong answer (Hasan 2006: 10). They are extraordinarily rare although again they demand quite some effort from students and can be assumed to promote higher cognitive processes (ibid.: 10). Based on the above considerations, I am now able to narrow down my study: it will only focus on quantitative aspects of digital communication in symmetrical and complementary relationships in classroom settings, leaving aside the content and relationship levels of messages as well as their interpunctuation. I will also evaluate the distribution of questions and exchanges between the teacher and the students. 5 3. Empirical findings on classroom communication In this section, I am going to present findings from various studies on the relation between TTT and STT. While there are copious amounts of studies on classroom discourse, very few actually cover talking times quantitatively. In order to gain a broader understanding, I will look at studies that took place in the past 30 years up until the present day. I will start with an overview of several studies to provide a general tendency of typical values of teacher and student talking times. After this, I will present a few select studies in more detail because each of them focused on interesting single factors: besides TTT, Hasan (2006) also researched the types of questions asked by the teachers, Hitotuzi (2005) studied two classes of different competence levels, as did Tsui Bik-May (1985), with the additional fact that one of her classes was English-medium while the other one was Chinese-medium. Those three studies were conducted in cultural contexts that are rather different from Germany, hence it is possible that there are external factors which influence TTT which would limit comparability. Therefore, I will also present the results from the DESI-Videostudie (Helmke et al. 2008) which was carried out in Germany as well as the study from Kampa (2012) which was carried out in Berlin. An extensive, though rather outdated, overview of descriptive sociolinguistic studies of classroom discourse can be found in Cazden (1986) and Chaudron (1988: 50-52). Klinzing and Klinzing-Eurich (1988), Seliger (1977), and Walsh (2002) conducted studies with a rather qualitative focus and can therefore complement the ones I am going to present here. Schwab (2009) carried out an extensive qualitative study in a German Hauptschule. 3.1. Teacher and student talking times Most research found TTT to be clearly dominating classroom time: Chaudron (1988: 51) quotes three studies where about 60 %2 of all moves are the teachers’, and two studies that found 70 % of moves were carried out by teachers. Only one of the six studies that he presents demonstrated instances where student talk amounted to such high numbers as 42-84 %, the median being 64 % (ibid.: 51). He therefore concludes that about two thirds of classroom time are attributable to teacher talk (ibid.: 52). All of the studies he references are represented in Table 1. 2 Whenever studies on teacher and student talk account for the time of silence, I will present those numbers here, too. Otherwise, percentages of teacher talk and student talk refer to total talking time and not to total lesson time. 6 study Bellack et al. 1966 Dunkin and Biddle 1974 Legarreta 1977 Enright 1984 Bialystok et al. 1978 Ramirez et al. 1986 TTT STT % median TTT median STT 70-89 15,1-57,1 61,3-68,8 60-80 11-30 42,9-84,9 31,2-38,7 20-40 61,7 60 77 35,6 70 38,2 40 23 64,4 30 Table 1: Results from empirical studies quoted in Chaudron (1988: 50-51). This result is confirmed by Hasan (2006: 13), Inamullah, Hussain, and Din (2008: 42), as well as Schönwälder (1988: 116), who found TTT to be between 44 % and 80 % in their studies (cf. Table 2 for their results). TTT % STT silence Schönwälder 1988 Hasan 2006 Inamullah et al. 2008 50-80 73 >44 20-50 27 <22 >33 elementary intermediate English Tsui-Bik-May 1985 Chinese 31,25 13,34 81,7 84,2 35,84 75,76 18,3 15,8 32,91 10,9 - study Hitotuzi 2005 Table 2: Results from Schönwälder (1988: 116), Hasan (2006: 13), Inamullah, Hussain, and Din (2008: 42), Hitotuzi (2005: 103), and Tsui Bik-May (1985: 17). Highlighted values are based on my calculations. Going into more detail, Inamullah, Hussain, and Din (2008: 41) present what they call the “two-thirds rule”, which states that two thirds of classroom time are spent talking, about two thirds of this time the teacher is the person talking and two thirds of this talking time is devoted to direct instruction. This confirms that teachers “verbally dominate the classroom” (ibid.: 41). However, these results are not unanimous. One study quoted by Chaudron (1988: 51) found very low values for TTT, ranging from 15,1 % to 57,1 % at a median of 35,5 %. The elementary group of Hitotuzi (2005: 103) had a TTT of 31,25 % and the intermediate group only 13,34 %. On the other extreme, Tsui Bik-May (1985: 17) found values between 81,7 % and 84,2 % for TTT (both studies are also included in Table 2). There are, however, a few more specific studies that I want to present because they provide interesting insights into the factors that substantially influence TTT and STT. 7 In his study on six EFL classrooms in Syria, Hasan (2006) concentrates on the relation between initiations and total words spoken. Hasan (ibid.: 13) found that 176 of 186 exchanges were initiated by the teachers and only ten by the students. The teachers said 4865 words while the students only held a share of 1784 words (ibid.: 13). Unfortunately, he did not provide an exact measurement of talking time. However, the numbers of words spoken by teachers and pupils provide a good analogue: teachers said 73 % of the words and students 27 % (my own calculation). If we assume that the average length of words is the same in student as well as teacher utterances we can use these numbers as if they represent TTT and STT, respectively. Hasan’s results confirm the older research findings reported in the preceding paragraphs. Notably, he also focused on the kinds of questions asked by the teachers. He found that out of 235 questions, 227 were display questions, eight reasoning questions and that there were no referential questions (cf. Table 3). He argues that display questions put significant constraints on student answers and promote one-word answers rather than full sentences. (ibid.: 11) class 4 type of question 1 2 3 display referential reasoning 70 0 2 35 0 1 12 0 0 16 0 3 5 6 total average 45 0 2 49 0 0 227 0 8 37,38 0 1,33 Table 3: Results from Hasan (2006: 11) on question types used by the teacher. Hitotuzi (2005) studied two of his own EFL classes in Brazil which had different learner competence levels, one elementary and one intermediate group, for two double lessons each. His findings are especially interesting as he tried to implement a learner-centred approach similar to the teacher in my study (ibid.: 98). This teaching approach is the reason why TTT was as low as 13 % in the intermediate group while STT amounted to 76 %. This exceptional result is also due to the fact that the first double-lesson consisted of small-group, task-based work and instructions had been given in the previous, un-recorded lesson. In the elementary group, TTT equalled 31 %, while STT was 36 %. (ibid.: 103) These astonishing findings are in stark contrast to most other research outcomes where TTT is much higher. There are almost no studies where TTT is below 50 %. The results point to the fact that teaching methods and activities implemented in class are key factors influencing TTT and STT. Another study was conducted by Tsui Bik-May (1985) in Hong Kong which is interesting because it compares two classes with a different language of tuition (cf. Table 2). She 8 analysed TTT and STT in a Chinese-medium class with a low level of English proficiency and an English-medium class with better English skills (Tsui Bik-May 1985: 16). Despite these substantial differences and the teacher of the stronger group being a native speaker while the teacher of the other group was a non-native speaker, she found striking similarities: TTT was at 81,7 % in the stronger, English-medium group and 84,2 % in the weaker, Chinese-medium group (ibid.: 17). The language of classroom discourse seems to play a decisive role here: if it is Chinese, especially weak students will be able to contribute more and longer utterances to the class than if they had to speak English all the time. This suggestion is confirmed by Tsui-Bik-May’s (ibid.: 24-25) finding that there were almost no features of typical native speaker non-native speaker conversation, not even in the classroom of the native speaker teacher. 3.2. DESI video study The study Deutsch Englisch Schülerleistungen International (DESI) was carried out in 220 schools throughout Germany in a proportional sample of school types and schools per Bundesland (Beck, Bundt, and Gomolka 2008: 13-14). The results of the study have strong implications for my own research project for several reasons: firstly, it is one of the very few large scale studies of TTT and STT; secondly, it was conducted in 2003 and 2004 and is therefore very recent (ibid.: 18); and thirdly, it was conducted in Germany and hence we can assume that the teachers share a certain understanding on student activation and classroom discourse with the teacher in my study. Among the methods used in the DESI study were surveys, tests, as well as video tapes of two lessons of the 105 classes that took part (Helmke et al. 2008: 346). As the authors also used questionnaires to ask teachers and pupils to self-evaluate their talking time, those results will also be presented here (ibid.: 351-352). The talking times are reproduced in Table 4. school type TTT % STT silence Hauptschule Realschule Integrierte Gesamtschule Gymnasium 65 73 75 63 35 27 25 37 - average 51 68 23 32 26 - Table 4: Results from DESI video study (Helmke et al. 2008: 350-351). 9 TTT came to 51 % on average and STT to 23 %, which leaves 26 % of time silent (Helmke et al. 2008: 350). Unfortunately, the values of the different school types are not provided including silences, but only without. STT was highest (37 %) at the Gymnasium, second highest at the Hauptschule (35 %) and as low as 27 % and 25 % at the Realschule and the Integrierte Gesamtschule, respectively (ibid.: 351). These findings are rather puzzling as they do not allow any clear cut conclusions to be drawn. When comparing school types to the amount of student talk, there was no positive or negative correlation between student competence and STT, as was found in the Hitotuzi (2005) study. For the most part, teachers under-estimated their own talking time considerably: the selfestimate was at 51 % while TTT averaged at 68 % (Helmke et al. 2008: 351-352). More than 30 % of teachers even thought their talking time was lower than 40 %, although this value was never reached in any of the videotaped lessons (ibid.: 351-352). 3.3. Kampa’s case study at a Berlin secondary school The Kampa (2012) study is much closer to my study not only in geographical terms, but also in temporal proximity, as it was conducted in 2012. He recorded three single (45 minutes), and two double (90 minutes) lessons in a Berlin EFL classroom at an Integrierte Sekundarschule (ISS) (ibid.: 33). He also used questionnaires to ask for students’ and the teacher’s assessment with regards to their individual speaking time and compared the self-evaluation with the actual measurements (ibid.: 21-22). His overall results are represented in Table 5. lesson 1 2 3 4 5 total % lesson time 39:50 1:26:30 42:04 1:28:05 41:44 4:58:13 100 silence 3:08 7:01 7:00 24:14 3:12 44:35 14,9 TTT 10:37 15:17 9:25 23:50 10:11 1:09:20 23,2 theoretical STT 26:05 64:12 25:39 40:01 28:21 3:24:18 61,8 theoretical SSC 5:58 53:18 12:55 2:14 6:45 1:21:10 27,2 effective STT 20:07 10:54 12:44 37:47 21:36 1:43:08 34,6 Table 5: Results from Kampa (2012: 33) in h:mm:ss. Theoretical STT is calculated by adding theoretical SSC and effective STT. Highlighted values are based on my calculations. In contrast to most other studies presented above, TTT was between 18 % and 27 % (Kampa 2012: 34) with an average of 23 % (my calculation). STT, on the other hand was at values between 45 % and 74 % (ibid.: 34) with an overall average of around 62 % (again my calculation). Silence accounted for approximately 15 % of the lessons. 10 These numbers are in stark contrast to the results of Hasan (2006), Tsui Bik-May (1985), as well as DESI (Helmke et al. 2008). Since, however, Kampa does not describe how the teacher in his study designed the lessons, we can only speculate about the teaching methods employed. But it stands to reason that they tried to implement a learner-centred approach as much as possible and succeeded in doing so very much. The results of the questionnaire are also of interest here. Students marked their individual perceived talking time after each lesson on a scale of zero to 18. The values were between 7,9 and 10,6 with an average of 9,7, which was slightly above the middle of the scale (Kampa 2012: 35). Kampa (ibid.: 41) concludes that students’ perception of their own talking time was close to their actual participation in class as he measured it in individual oral contributions. Notably, the desired STT is always higher than perceived talking time. Values range from 14,0 to 14,7 on the same scale (ibid.: 35). This is especially interesting when we think of the relative high level of STT found in the study’s lessons. But it seems that the pupils were not content with that much talking time and wanted even more. In every lesson, there were 19 learners (86 %) or more who wished to have talked more than they actually did.3 Between seven and 11 (30-47 %) even wished to have talked much more than they did, which is expressed by a difference greater than four between perceived and desired STT. (ibid.: 37) With regard to TTT, the pupils were much more content with what they experienced in class; although they estimated their teacher’s talking time at the upper end of the scale at values between 14,3 and 15,6, they somewhat surprisingly wished it to have been even higher in three out of of five lessons with a difference of 0,5 to 1,1 between perceived and desired TTT (ibid.: 38). These numbers suggest only a small wish on the side of the learners for their teacher to talk more. Yet, the overall high estimate of their teacher’s talking time is all the more surprising if we consider that TTT as exceptionally low in this class compared to other studies. Overall, Kampa’s study shows that the students in his sample were able to adequately estimate their individual talking time. Furthermore, they actually wanted to participate orally in the language classroom and also expressed this wish, although their talking time was already much higher than in other classrooms studied. 3 It needs to be noted here, that there are errors in the first two columns of Table 4 on p. 37 (Kampa 2012): the numbers of pupils add up to 35 and 30 in the first and second column while there were 23 and 22 students present, respectively (ibid.: 37). However, the correct numbers can be derived from Table 11 in the appendix (ibid.: 56-57). 11 4. Teacher talk and student talk: Is there a right balance? In this section, I am going to answer the title question “Is there a right balance between TTT and STT?”. In order to do this, I am going to compare important teaching methodologies with a special focus on their stance towards teacher and student talk. I will divide the methodologies into two camps: pro teacher talk and pro student talk. As almost none of the approaches are strictly one-sided, this is a simplified representation, but the tendencies are there and will become clear in my presentation. As a counter-point, I include three other sources as well: guidelines from the Berlin education authority as well as two EFL textbooks. After a short introduction to each position I will summarise the role they intend for teacher and student talk in order to answer the title question. 4.1. Pro teacher talk In this section I am going to present three methodologies that favour teacher talk over student talk, or, to be more precise, that do not ascribe any value to learner utterances with regards to language learning. These are Grammar-Translation, Total Physical Response, and the Natural Approach. 4.1.1. Grammar-Translation Grammar-Translation was the dominant methodology in the 19th century, mainly used to teach Greek and Latin. It is based on working with original texts and seeks to enable access to classic literature. According to this idea, students can achieve this best by “consciously memorising the grammatical rules and lexical items of the target language” (Knight 2001: 148). Besides pure learning by heart, the approach is also focused on the sentence as a central unit and students have to translate sentence by sentence from and into the target language. (ibid.: 148) Although Grammar-Translation had declined in popularity by the end of the 19th century, it is still used today as a method for learning the ancient languages (personal correspondence with a Latin trainee teacher). It was mostly the Reform Movement that criticised Grammar-Translation, shifted the focus to the primacy of speech and suggested various different methodologies that are more widespread now in modern language teaching. (ibid.: 148-149) It follows from these principles that student talk does not play an important role in language learning; the role of oral speech or communication in the target language is only of 12 secondary importance. Student talk is only a means in which to respond to the teacher’s requests but not an end in itself. 4.1.2. Total Physical Response During the 1960s and 1970s, several methodologies were developed that could be described as Humanist because they consider the learner as a whole human being. One of them is Total Physical Response (TPR), which links the process of language learning to physical activities. The teacher gives verbal instructions, to which the pupils only respond physically. As soon as they feel that they are ready to, they are also encouraged to respond verbally. As this kind of interaction is limited to very concrete and immediate concepts, TPR is mainly used at the beginner level. (Knight 2001: 154) TPR limits student talk to an absolute minimum by asking pupils to speak only if they want to. Teacher talk is central, but is not assigned a more significant role than that of simple instruction. Yet, teacher talk is the only kind of talk planned to happen in this approach and therefore its categorisation lies in the pro teacher talk camp. 4.1.3. The Natural Approach Although it is in principle a learning theory, and a language teaching methodology by extension of such principles, I include the Second Language Acquisition Theory (SLA) by Krashen and Terrell (1983) in this section, because it takes quite an extreme stance on the question of TTT and STT. SLA, also referred to as the Natural Approach, has the same goals as communicative language teaching, but differs significantly in its view on the learning process (Knight 2001: 159). According to the theory of SLA, there is a crucial difference between acquisition and learning. Acquisition is defined as the natural, sub-conscious process of picking up a language by mere exposure, like children do with their first language. Learning, on the other hand, describes the process of consciously studying the rules and developing explicit knowledge about a language’s grammar. According to the theory, every utterance is initiated by the acquired system and the learned competence is only used to check for grammatical correctness, which is called the monitor. (Krashen and Terrell 1983: 18, 30) The central part of the learning theory is the Input Hypothesis: This hypothesis states simply that we acquire (not learn) a language by understanding input that is a little beyond our current level of (acquired) competence. (ibid.: 32, original parentheses) 13 Therefore, listening and reading comprehension are of primary importance for this concept. The input need not be finely tuned to the learner’s level of competence, as they derive the meaning of an utterance from the context in which it is embedded. Extra-linguistic information, as is often given by caregivers to their children, and also teachers to their pupils, simplifies this task. (Krashen and Terrell 1983: 32) This idea bears a striking resemblance to a concept by Soviet psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1978): the zone of proximal development. In his theory of mental development, learning (here used in the more general sense) takes place during social interaction whenever an individual is confronted with challenges that just exceed their current level of competence. According to this view, tasks and language input need to be provided in this zone of proximal development in order to activate cognitive processes that lead to an increased understanding. (ibid.: 24, 86) Because teacher talk can never be adjusted to the competence of every individual student, Krashen and Terrell (1983: 35) describe it as “roughly tuned” and argue that this is the best input that can be provided; firstly, it is in the zone of proximal development of more than one pupil at a time, and secondly, it is more similar to other non-pedagogical communicative situations, if the teacher revises and reviews the language, as opposed to minutely preparing instructions that accurately fit the anticipated level of the learners. (ibid.: 35) Krashen and Terrell (ibid.: 32) conclude therefore, that both learning and acquisition can take place in the language classroom and that teacher talk plays a central role in this process. Although subsequent research overturned claims from SLA such as the acquisition-learning distinction, comprehensible input remains as one — though certainly not the most — important factor in language learning (Knight 2001: 159). For this reason, SLA provides a strong argument for the value of teacher talk, as long as it provides comprehensible input. This is even at the expense of learner talk, since SLA prefers correct teacher talk over faulty student talk. 4.2. Pro student talk In the pro student talk camp are Audio-Lingualism, The Silent Way and currently the most dominant methodology, Communicative Language Teaching. 4.2.1. Audio-Lingualism During the Second World War, language training became an important part of military strategies and so, teaching programmes were developed in the United Kingdom and the United States of America. According to Knight (ibid.: 149), the US-American programme was 14 an important influence on the so-called audio-lingual method, which is based on a structural linguistic view of language as well as on behaviourist psychology. Consequently, in this method language was and is perceived as primarily an oral system that is governed by rules, and structures. Learning therefore takes place in the form of drills, in which learners receive a stimulus to which they have to respond. (Knight 2001: 149) The idea of the student is somewhere between passive and active: while on the one hand they are seen as “empty vessels” (ibid.: 151), they still need to be active in the repetitive tasks so that the target language can become their “habit” (ibid.: 152). Although Audio-Lingualism aims at communication, language learning does not happen by employing meaningful conversation, but through self-monitored repetitive tasks in the language laboratory (ibid.: 151152). The approach is very teacher-centred although their autonomy is rather limited; correct application of the materials from the rigid syllabus is paramount. This is, however, eased by the fact that the teacher also has to serve as a language model, judge student output and manage classroom activities (ibid.: 152). Audio-Lingualism embodies the historical shift from a purely grammar-based view of language to one that understands communication as behaviour in Watzlawick’s sense. Teacher and student talk play a more important role in the process of language learning, although both are strongly educationalised and do not resemble real-life communication at all. Teacher talk serves as language input for learners, and student talk is essential only as a repetitive means in which to learn a new habit. It needs to be pointed out that it is mainly in a quantitative sense that student talk is to be extended in language teaching. 4.2.2. The Silent Way Similar to TPR, The Silent Way is a Humanist approach and was developed in the 1970s by Gattegno (1972). It aims at learner independence and at the development of the ability to assess linguistic accuracy. However, the way to achieve this is very particular. The teacher has to be silent most of the time and instead works with coloured wooden sticks (so-called Cuisenaire Rods), coloured pronunciation cards (Fidel Charts) and vocabulary charts. The pupils are responsible for their own learning, self-assessment and peer control is encouraged. (Knight 2001: 152-153) Although this does not necessarily lead to a simple shift of talking time towards the learners’ side, The Silent Way tries to limit teacher talk to an absolute minimum. Instructions, error corrections and feedback still need to be given, albeit not verbally, but silently. This may take even longer when using the tools explained above, as opposed to verbal clues. Student talk, on the other hand, takes a more emphasised role as it is not only needed for 15 diagnostic means and error correction by the teacher and fellow pupils, but also serves as language output for the whole class. The Silent Way is a rather marginal concept in modern language teaching but is included here due to its extreme position with regards to teacher talk. 4.2.3. Communicative Language Teaching Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) is the currently dominant methodology of teaching modern foreign languages (Knight 2001: 155). It aims to enable learners to “communicate successfully in the target language in real situations” (ibid.: 155). This means that the conscious understanding of rules is not as important as in some of the other approaches. Language is perceived as a system in use rather than an abstract concept made of rules and structures (ibid.: 155). CLT puts communicative competence at the centre of language teaching and there are three principles that form the core of it: a) the communication principle, b) the task principle, and c) the meaningfulness principle (ibid.: 155). According to those principles, language learning is promoted by a) real communication, b) the usage of language for the completion of purposeful tasks, and c) if the language used is meaningful to the learner (Richards and Rodgers (1986: 72) quoted in Knight (2001: 155)). In the sense of the dictum preceding this dissertation, learners are expected to become more independent and actively work with the material as well as the other learners (Knight 2001: 158; Breen and Candlin 2001: 14). The pupils need to negotiate among themselves, as learning is understood to take place in a social context, and monitor each other (Breen and Candlin 2001: 18). The importance of symmetrical communication and its benefits for language learning are emphasised by van Lier (2001: 100-104). The teacher, on the other side, takes a less dominant role and becomes a facilitator, participant, guide, organiser and “researcher-learner” (Knight 2001: 155) in the communication and learning process as well as someone who analyses the language needs of the learners and decides upon the next steps to take (Breen and Candlin 2001: 17-18). Therefore, CLT takes a balanced position towards teacher talk, as it is both valued as important language input and as a means of communication from the teacher’s side, but it is also limited by the strong bias for learner-learner interaction. With regards to student talk, CLT is unambiguous: student talk is not only necessary for the roles that learners play in the communicative language classroom, but it is also the central ingredient in the process of language learning itself; teachers must provide many opportunities for pupils to talk among themselves in symmetrical relationships. 16 4.3. Other sources As a counter-point to the strong positions of the preceding theories, I am going to present three other sources in this section: first, the guidelines from the Berlin educational authority, the Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Wissenschaft, because they unfold a certain normative power in the discourse. Following this, I will describe the stances taken by two EFL textbooks, Haß (2006) and Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann (2015). This is due to the fact that textbooks review the most up to date teaching methodologies and combine them in a collection of didactic guidelines. This means that they are usually less biased than the works of authors of learning theories themselves and therefore help teachers in planning and creating adequate, modern language lessons. 4.3.1. Recommendations by educational authorities The Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Wissenschaft (henceforth SenBJW ) is the top educational authority in Berlin and was formerly known as Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung, (SenBWF) as well as Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Sport (SenBJS). Neither the current nor the future core curriculum have any recommendations on the amount or practice of teacher and student talk. However, functional communicative competence (funktionale kommunikative Kompetenz) is the central goal of EFL in Berlin and this includes speaking as a competence (SenBJS 2006: 10-12; SenBJW 2015: 10, 25-26). The publications for English language teachers — the so called Englisch-Fachbriefe also do not give any guideline as to an optimal balance of TTT and STT. However, there is one document in the series for language teaching and German as a Second Language (Deutsch als Zweitsprache) that actually refers to teacher and student talk: Damit die Schülerinnen und Schüler inhaltliche und sprachliche Lernprozesse integrieren können, brauchen sie Lernsituationen, in denen sie aktiv über die Fachinhalte sprechen und sich austauschen können. Für die Unterrichtsplanung heißt dies, dass Zeit für solche Interaktionen vorzusehen ist und der Redeanteil der Schülerinnen und Schüler generell mindestens (!) so groß zu halten ist wie der der Lehrkraft. (SenBWF 2008: 5) It is important to note that this recommendation refers to the language used in content subjects such as mathematics, history, or music and are taught in German. It aims at enabling students with a first language that is not German to further their German skills and acquire the German terminology used in these fields. If, however, student talk is supposed to be evenly balanced with teacher talk in content subjects where language plays the role mainly as medium and not as the sole purpose of 17 the lesson itself, language teachers are by all means supposed to allow their learners to talk at least as much as they themselves speak in class. Therefore, it is sound to apply these guidelines to TEFL classes and take them as orientation value. 4.3.2. Haß: Fachdidaktik Englisch In the section on oral skills, Haß (2006: 92) criticises the traditional focus on written language and suggests that it be reduced in favour of speaking. He defines speaking not as students repeating items to rehearse pronunciation and/or reading out text passages. Speaking requires real speech acts of intentional speaking with a message and a communicative aim in mind (ibid.: 92). He argues that it cannot be accepted that up to 30 % of pupils do not say anything in some lessons — an aspect which will be analysed in my study, too — and demands that students speak more in two ways: firstly, everyone has their say, literally, in every lesson, and secondly, students individually get to say more in each lesson (ibid.: 96). From a qualitative point of view, he demands that the language used in the classroom be authentic and be situated in genuine scenarios of the lesson (ibid.: 97). In order to increase individual STT, he suggests a few methods for dialogues, among them flow-chart strategy, surveys, interviews, and pro & con debates (ibid.: 98-99). But there are also a few techniques and principles that can be employed to achieve the desired goals: • directing questions and impulses to all students and giving enough time to respond • encouraging more student-student interaction • using English as classroom language with only rare exceptions • employing less lecture-style instruction and more partner and group work methods • supplying more classroom activities • exercising less teacher control and offering more creative tasks (ibid.: 99) Clearly, Haß is in line with the basic tenets of CLT and is trying to promote this teaching methodology among the readers of his book. 4.3.3. Grimm, Meyer and Volkmann: Teaching English Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann (2015: 30) situate the question of a right balance between TTT and STT not only in actual teaching practice but also argue that teachers need to have a “sound knowledge of pedagogy” which they should use to reflect on their interactional classroom patterns from a pedagogical perspective. According to them, teachers need to 18 know that pupils learn languages best if classroom communication is authentic and true to real-life communication. Additionally to the reflection of teaching practice, they suggest that teachers monitor their own lessons themselves or ask colleagues to sit in on their lessons and give feedback with regards to classroom communication. (Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann 2015: 235) They criticise classroom communication as inauthentic and deficient because of its strong asymmetry, too little STT, too much TTT, and the problematic structure imposed by the IRF exchange (ibid.: 236). Quoting Müller-Hartmann and Ditfurth (2004: 29), they argue that the IRF exchange impedes the quality of language input […] and restricts learners’ opportunities for language production and conversational interaction which again play an important part for second language acquisition. (quoted in Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann 2015: 239) In order to solve the problem of IRF, they suggest that teachers generally speak less, give learners more time to answer questions, and reduce monologues (ibid.: 240). Additionally, the questions teachers ask should become more varied and display questions should be reduced. Additionally, they propose the increased use of “verbal stimuli” (ibid.: 240) that encourage student input which is more similar to self-initiated contributions than mere answers to questions. (ibid.: 240) Interestingly, and contrary to Haß (2006: 98), they state: In spite of aiming at overall more student talk time, teacher talk should not be seen as inherently detrimental to good communication and good learning. (Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann 2015: 241) They justify this by arguing that well-tuned teacher talk is highly valuable language input for students and quote Hattie (2009: 22), who argues that “what teachers do matters” (quoted in Grimm, Meyer, and Volkmann 2015: 241, original emphasis). The authors of the second textbook state that teachers should try to improve on the quality of their talk and of communication in the language classroom in general by making it more authentic to real-life conversation, while Haß advocates an increase of STT. Although these recommendations are only gradually different from each other, they still emphasise independent aspects and may lead to different results, if followed through. 19 4.4. Conclusion I will now conclude this section by discussing the various approaches presented and try to answer the title question. The approaches in favour of teacher talk emphasise its importance for students as language input. Interestingly, pro student talk approaches — except The Silent Way — agree with this and argue that students need language role models upon which to orientate. The main difference between the two camps is the way they conceptualise and position student talk in the process of language learning: teacher talk supporters perceive learner talk as a mere means that is deficient and something that does not benefit language learning. The other camp refutes this, pointing to the importance of active language use in order to get learners experienced in communicating in a foreign language. In their conception, pupil talk is not only a means for better learning, but is an end in itself; making students talk among each other in a foreign language is the highest goal of language teaching because communication with others is what language is all about. There is no one-size-fits-all ratio that can be applied to every language lesson. Instead, a right balance can only be given with regards to the goal of a specific lesson at hand and can only very roughly be claimed for language teaching in general. Yet, the recommendations from SenBWF can be used as a sensible minimum value: at least 50 % student talk per lesson. Especially when looking at the opportunities provided by SSC, we can overcome the “seesaw relationship” (Dellar 2004) of STT being positioned against TTT, which sees the one increased at the cost of the other. SSC, on the other hand, provides the opportunity to have as many students speaking at the same time in groups or pairs. By using this advantage, teachers are able to increase the individual talking time of students by using cooperative methods in class. While they only need to give away say ten minutes of TTT, they gain at least ten times five — if there are five groups working on a task in a given phase — minutes of SSC. The drawback is of course that the teacher cannot monitor — and if necessary, correct — all that is being said during SSC phases. To conclude this chapter, I propose a guide value of at least 50 % combined STT which would be split up between STT and SSC so that learners can practice language in symmetrical communication and also be monitored by their teacher. If the rest of the lesson is spent with teacher talk and not too much silence, there will be enough language input for the learners to process. 20 5. Design of the case study First and foremost, I would like to state that this is a descriptive study in an actual classroom that does not rely on experimental design and therefore requires no pre- or post-tests (Williams 2012: 542). My study combines direct observation via audio recordings, interaction analysis with regards to the collected data, and introspective methods due to the information gained by the questionnaires (ibid.: 543). In this section I am going to describe the case study that I carried out. I reproduce the same methodology that Kampa (2012) used in his study, and my empiricism is based on the works of Albert and Marx (2010), Swann (2001), and Williams (2012). In the following, I will explain the aims and the way in which I anonymised the data. I will continue with a description of the sample, the instruments, and how I analysed the data. I will finish with an assessment of the quality criteria. 5.1. Aims The scope of my study is limited. Most importantly, I want to answer the research question “How much do teachers talk in German EFL classrooms?” for one single case: this teacher in this class in these five lessons. In order to do this, I will supply quantitative results on the distribution of TTT, STT, SSC and silence for each individual lesson and each individual participant. I will also provide a detailed account of the numbers of turns and the types of questions asked by the teacher as well as the students per lesson and in total. On the qualitative side, I hope to find out how satisfied the teacher and the students were with the lessons through a questionnaire analysis. On a more abstract level, that this study raises awareness for talking times among all participants. It would follow, that more studies lead to more teachers focusing actively on talking times. Having such precise data enables teachers to change their teaching behaviour when necessary (Klinzing and Klinzing-Eurich 1988: 213). 5.2. Anonymisation As a precondition to permit my case study, Mr. E. from SenBJW demanded that the names of the pupils and the teacher not be retrieved or used at all. Therefore, I assigned a number to each learner and asked them to remember it so they they used the same number throughout the whole time. 21 At the beginning of each lesson I placed a slip of paper with their number in front of each student and created a seating plan for the lesson. Thus, I was able to identify and refer to pupils consistently over the whole course of my study. They also used their code in the questionnaire so their names were not noted down anywhere. 5.3. The sample In this section, I am going to describe the school, the learning group, the teacher, and the lessons that I studied. 5.3.1. The school Kampa (2012) obtained his results from an ISS in Berlin. Because I want to contrast his findings with a different type of school, I chose a Gymnasium since student competence is expected to be at a higher level. The school in which I conducted my study is located on the outskirts of the city and has English as first foreign language, but otherwise no peculiarities that are relevant to the focus of my study. It is attended by over 700 pupils from all social backgrounds. Permission to conduct the study was given by SenBJW on the 21st of December 2015. 5.3.2. The students The group I studied consisted of 21 learners in an 11th grade elementary course (Grundkurs). I taped their lessons in the second semester of their final two-year-period (Oberstufe). This also means that the composition of learners in this group was still rather new to everyone, although most of them probably knew each other from the class phase in the secondary level. Although I am not necessarily interested in the effects of gender, I am going to use names that match the gender of the students as I understood them. The names are taken from the television series South Park. According to my reading, the class has 12 female and 9 male learners. The seating plan is reproduced in Figure 1 and shows the seating position of the learners, the teacher’s desk, my place, as well as the location of the microphones. The competences of the students are mostly elementary. There are a few pupils with outstanding knowledge and skills, but this is mostly limited to a certain area such as a very wide vocabulary or ability to express themselves. 22 windows 14 16 windows whiteboard smartboard door computer 10 18 researcher teacher 15 17 19 m2 1 2 12 11 13 6 5 3 8 9 4 21 m1 20 7 Legend: numbers 1-21 refer to students; m1 = Trekstor device; m2 = iPhone Figure 1: Seating plan of the class. 5.3.3. The teacher The teacher conducting the lessons was a young trainee teacher in the second semester of her Vorbereitungsdienst. She finished her university studies in 2015 and began teacher training directly after. Apart from this class, she was also teaching a secondary-level class in German at the same school and attended courses at two practical seminars (Fachseminare) for each of her subjects as well as one seminar on pedagogy in general (Allgemeines Seminar). In an interview prior to my recordings, she told me that their instructors advised them to implement learner-centred methods and cooperative tasks as much as possible. She stated that these methods were fully in line with her own preferences for good language teaching and that she would try to activate learners as much as possible in the lessons that I was going to tape. Therefore, the results from my study have to be scrutinised carefully and may not reflect her average style of teaching. More interestingly, however, they can be taken as a measure of what is possible in terms of reducing TTT and increasing STT and SSC by employing up to date approaches. 5.3.4. The lessons I recorded five lessons in January and February 2016. Lessons two, four, and five were double lessons, i.e. about 90 minutes long; one and three lasted approximately 45 minutes. All in all, this makes up eight single lessons. In order to reduce the “observer’s paradox” (Swann 2001: 23 324) or Hawthorne effect, which changes the subjects’ behaviour due to their being recorded, I taped one more lesson prior to lesson one and discarded the results. The double lessons usually had a break of 5-10 minutes which was removed from the data because no teaching was happening in this time. Lesson one was a single lesson, which was focused on correcting the homework and finishing up group work from the lesson before. Lesson two was a double lesson with an eight-minute break which was deleted. It started with a 14-minute vocabulary test — which was also removed from the data — and was very teacher-centred for the rest of the class. Lesson three was a single lesson where two or three of the absentees from the lesson before had to do the vocabulary test in the first nine minutes. The rest of the group had to do a work sheet individually, which was therefore coded as silence. The remainder of the lesson was rather teacher-centred but had a short fish bowl phase at the end. Lesson four was a double lesson with a six-minute break which was deleted. Two students, who had missed the two lessons before, had to do the vocabulary test while the rest of the group was instructed to do partner or group work, which therefore was coded as SSC. Then, the six thinking hats method was used and the learners turned an individual task into a phase of group work by themselves. Lesson five started with the finishing of posters that were started in the lesson before. Then there was a gallery walk. After this, there was a five-minute break and a vocabulary test was held, which were both deleted from the data. Then, a teacher-centred episode followed and finally, the think-tank method was used to make the learners discuss two hypotheses. 5.4. Instruments In the following, I am going to describe how I made the recordings and the questionnaire. 5.4.1. Audio recordings I did not intervene in classroom interaction and I clearly told the students that I was not interested in what they were saying but only how much they and their teacher were talking. This was to minimise the impact of my study on the pupils’ behaviour. To tape the lessons I used a portable TrekStor music player with a recording function, which was placed in the middle of the room, as well as an iPhone that had Voice Record 24 Pro4 installed, which was located on the teacher’s desk (cf. Figure 1). After the analysis of the first two lessons, it emerged that the recordings made with the music player fulfilled the requirements by far. I decided to dispense with the iPhone, since Swann (2001: 327) recommends to keep technology simple and unobtrusive and also because the rules of the school forbid mobile phones on desks during lessons. Due to the quantitative nature of my study, it was enough to create field notes in order to ascribe utterances to the pupils producing them; a transcript was not necessary (ibid.: 328). During the lessons, I jotted down the number of the pupil saying something as well as one or two keywords that would later allow me to attribute the utterance to the learner who produced it. This method proved to be feasible also during periods of fast exchanges between teacher and students. In order to code the audio file, I used InqScribe5 , a programme that provides an easy way to create time stamps in a text file that correspond to a specific audio file. An example from lesson four is reprinted in Figure 2. [00:45:58] [00:46:07] [00:46:32] [00:46:45] [00:46:50] [00:46:56] [00:47:16] [00:47:36] [00:47:45] [00:47:53] [00:48:13] [00:48:35] [00:49:13] Teacher,reasoning Student 2 Student 6 Silence Teacher Student 15 Student 18 Silence Student 12 Student 18 Student 6 Student 15 Student 18 [00:49:40] [00:50:02] [00:50:08] [00:50:11] [00:50:27] [00:50:41] [00:50:48] [00:51:19] [00:51:38] [00:52:17] [00:52:26] [00:52:28] [00:52:36] Student Student Student Student Student Silence Student Student Student Student Student Silence Teacher 12 15 12 15 12 10,sinitiate 6 1 12 1 Figure 2: Coding example from lesson four. The time stamps refer to the beginning of the respective phase or turn. Each phase or turn is ended by the beginning of the next. I coded silence when there was a pause of two seconds or longer, for instance when the teacher was waiting for a response or the students were doing individual tasks. This is because individual work belongs to the lesson and pupils often started communicating with others during their individual tasks after a few minutes, which was then coded as SSC. I re4 This is a free software that can do high quality audio recordings and can be downloaded in the Apple App Store for free: https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/voice-record-pro/id546983235?mt=8. 5 The free trial version is available at www.inqscribe.com and is sufficient for my needs. 25 moved long silent episodes when the pupils had to do vocabulary tests because absolutely nobody was supposed to speak, and therefore no chance was missed to increase STT. Additionally to the participant identifier, I included a second code to denote the turn type, if applicable: there are display, reference and reasoning to refer to teacher questions as defined in Section 2.3, and s-initiate and s-question on the students’ side. An s-initiate is coded when a pupil initiates a turn by themselves, such as a suggestion or a correction to another student or the teacher. An s-question is coded when a learner asks a question, for instance for the meaning of a word or regarding a task that is to be done. 5.4.2. Questionnaire There are several design criteria for the questionnaire: brevity, clarity, and anonymity, which will be explained prior to the actual structure. The teacher and student questionnaires are reproduced in Figures 3 and 4 in the Appendix (pp. 41-42). As the questionnaire is handed out after every lesson, it should not take long to complete. This is achieved by two means. For one thing, the questions are very easy and the first two are repeated. For another, the participants only need to put a cross on a position on the scale that fits their estimate; they need not use numbers or elaborate on anything. In order to get plausible results, it needs to be clear what the questionnaire asks for. This may not be a problem in an 11th grade class, but should nevertheless be considered. To help with this, the questionnaire is in German. Anonymity has to be ensured. For this, the top right corner has a box labelled Nummer where the pupils enter the number assigned to them in the first lesson. Thus, it is possible to link the utterances from the field notes to the answers in the questionnaires without using their names. I based the design of the questionnaire on Kampa’s (2012: 21-24) and modified it slightly. My questionnaire includes a fifth question that is, like the four before, to be answered by a mark set on a scale. It ranges from gar nicht (not at all) to sehr viel (a lot) at questions one to four and from gar nicht to sehr gut (very good) at question five. In contrast to Kampa, I added seven vertical lines on the scales, creating six boxes so that the subjects have a better orientation of where their mark is located at. After a short description of the questionnaire, the first question asks the student or teacher to estimate how much they themselves talked in the lesson that just finished, i.e. their perceived talking time. The second question asks whether they would have liked to talk more or less, i.e. their desired talking time. Questions three and four enquire about the same information just with regards to the other group: students have to answer it with regards to 26 their teacher’s talk and vice versa. The fifth question asks for an evaluation of the lesson. During the introduction of the questionnaire, I explained that this question was meant as an estimate with special consideration of TTT and STT. Finally, I added a voluntary comment field, where the participants could explain or add any information they thought important, but this was rarely made use of and will therefore not be used in the final presentation of the results. I tested both brevity and clarity in the Hawthorne session and it emerged that the learners had no problems with understanding what was being asked and could fill it in quickly. Therefore, no changes were necessary after this pre-test. 5.5. Analysis The analysis of the audio recordings is straightforward; the way in which I coded the data means that they can easily be evaluated with a spreadsheet programme like Microsoft Excel, which counts the length and number of turns of each participant, and calculates the overall lengths of TTT, STT, SSC and silence, as well as their means and medians. The same applies to the questionnaire. The participants’ answers were ascribed a value between 1 and 6 according to the box in which they put their marks. Subtracting the desired talking time (the value given in questions 2 and 4) from the perceived talking time (the value given in questions 1 and 3) yields the difference of perception and desire (DPD). Because all participants were asked for the talking times of both speaker groups, DPD can be calculated for TTT and STT from both perspectives, students and teacher. If DPD is a negative value, the participant thinks the talking time is too low and they would have desired more. If DPD is zero, talking time is exactly as the participant desires it to be. If it is above zero, it is too high and should be reduced. The minimum and maximum values for DPD are -5 and 5, respectively. The fifth question asks the participants about their general contentment with the lesson. The line contains six boxes ranging from not at all (value of 1) to very good (value of 6). Hence, there are no negative values possible but only values between 1 and 6. 5.6. Quality criteria Finally, the quality criteria for empirical research have to be met as well: first, reliability asks whether a measure can exactly evaluate the construct. As in this case the speech events can be determined precisely as to their length in seconds and their number and type, reliability is fulfilled. (Albert and Marx 2010: 29-30) 27 Secondly, objectivity demands that a measure is independent of the person taking it. By recording the lessons, I make sure that the results can be controlled by a second person and that things I might have missed during the session can be examined from the tape. I have no personal relations to any of the students or the teacher nor any interest in shaping the results in any given direction. An unbiased researcher is one of the main requirements for objectivity, as is given in this case. (Albert and Marx 2010: 30) Finally, validity asks whether the method really measures what it supposes to measure (ibid.: 31-32). Due to the very immediate subject of investigation, the constructs which I am trying to measure are operationalised qua definition of the concepts in Section 2. This means that when I claim to measure the length and number of utterances given by students in a classroom setting while everybody else is listening, it is safe to argue that this construct can be measured by analysing the audio tapes and therefore, construct validity is given (ibid.: 33). Yet, there are qualifications to be made with regards to validity: since the teacher informed me about her intention to focus on learner activation as much as possible (cf. Section 5.3.3), my results can only be seen as internally valid and cannot be generalised, neither to her general style of teaching, nor to that of other teachers (ibid.: 31). 6. Results In this section, I will present the results. I will start with the findings on talking times, continue with the kinds of questions asked and then come to the allocation of turns. After that, I will present the findings from the questionnaire’s evaluation. I will structure this according to the question groups in it: first, the difference between perception and desire (DPD) with regards to TTT, then referring to STT, and finally the general contentment with the lessons. 6.1. Talking times Table 6 shows the values measured for teacher and student talking times and silences. To enable better comparability, Table 13 in the Appendix shows the same lessons, but with silences removed, and the percentages refer to talking time, not lesson time. Although I think this is methodically wrong, since most forms of silence (for exceptions cf. Section 5.4.1) belong to teaching, this additional representation is necessary because many studies provide their results without values for silence. Therefore, I am going to use the values from Table 6 if not noted otherwise. In the last column I added the values of STT and SSC in order visualise 28 the total time the pupils were allowed to talk. I will refer to this value as combined student talk(ing time). There are three more tables relating to talking times in the Appendix: Table 12 presents the overall talking times of all students together with a ranking of the teacher according to her estimate of their talking times. Table 14 shows the numbers of active and silent learners per lesson. Table 21 provides an individual breakdown of talking times per student and lesson. lesson lesson time silence TTT STT SSC STT+SSC 1 % 45:16 100 2:24 5,3 15:17 33,8 8:19 18,4 19:16 42,5 27:35 60,9 2 % 1:13:52 100 18:45 25,4 29:29 39,9 23:33 31,9 2:05 2,8 25:38 34,7 3 % 44:59 100 13:10 29,3 15:23 34,2 15:23 34,2 1:03 2,3 16:26 36,5 4 % 1:28:23 100 8:38 9,8 19:52 22,5 34:00 38,4 25:53 29,3 59:53 67,7 5 % 1:18:04 100 4:58 6,4 15:04 19,3 10:31 13,5 47:31 60,8 58:02 74,3 total % 5:30:34 100 47:55 14,5 1:35:05 28,7 1:31:46 27,8 1:35:48 29 3:07:34 56,8 Table 6: Teacher and student talking times in h:mm:ss. STT+SSC are referred to as combined student talking time. TTT ranges from 19,3 %6 in lesson five to 39,9 % in lesson two. Since time is measured in seconds — an interval scale — it is possible to calculate a mean value for all five lessons, which is 28,7 % (Albert and Marx 2010: 110, 116). STT comes to a mean of 27,8 % over the whole course of lessons which is only one percent less than TTT. However, its range is wider, spanning from 13,5 % in lesson five to 38,4 % in lesson four. The mean value of SSC is 29 %, which even tops TTT. It has the widest range, going from 2,3 % in lesson three to 60,8 % in lesson five. As mean values can be distorted by outliers, the median is often a good way to check for the plausibility of the measure of central tendency (ibid.: 117). In this case, the median is 29,3 %, which confirms the validity of the mean. Together, STT and SSC add up to 56,7 % and make up more than half of the lesson time. Silence ranges from 5,3 % in lesson one to 29,3 % in lesson three and its mean is 14,5 %. 6 Because I monitored lessons of various lengths, I will refer to the values in percent rather than absolute times. Percent are independent of lesson time whereas the use of absolute values would always need the clarification whether they refer to a single or double lesson. 29 6.2. Question types The number and types of questions used by the teacher and the students are represented in Table 7. To allow for an easier comparison, Table 15 in the Appendix shows the values for teacher questions only. lesson display teacher questions referential reasoning student question initiate total 1 % 5 14,7 10 29,4 5 14,7 14 41,2 0 0 34 100 2 % 39 47,6 9 11 24 29,3 10 12,2 4 4,9 86 100 3 % 13 33,3 8 20,5 15 38,5 3 7,7 3 7,7 42 100 4 % 5 10 18 36 12 24 15 30 3 6 53 100 5 % 12 57,1 3 14,3 5 23,8 1 4,8 0 0 21 100 total % 74 31,4 48 20,3 61 25,9 43 18,2 10 4,2 236 100 Table 7: Question types asked by the teacher and student initiatives. Display questions are most frequent with 31,4 % and a total of 74. Their range spans from 10 % to 57 %. Referential questions were used 48 times which equals 20,3 % of all questions asked. Spanning from 11 % to 29,4 %, their range is more limited than that of display questions. Reasoning question are very common with 25,9 % and a total of 61. Their lowest share was 14,7 % and their highest 38,5 %. Student questions are only slightly less frequent than referential questions: they total 43 or 18,2 % when included in the calculation with teacher questions. Student initiatives are very rare; there are 10 in total which equals 4,2 %. 6.3. Turns The numbers of turns per lesson are represented in Table 8. Teacher turns range from 49 % to 61,6 % and their mean is 55 %. Student turns have an equally small range spanning from 38,4 % to 51,8 % with a mean of 45 %. An individual breakdown of the number of turns per student and lesson and their average length is represented in Table 16 in the Appendix. 30 lesson teacher students total 1 % 68 58,6 48 41,4 116 100 2 % 197 61,6 123 38,4 320 100 3 % 107 48,2 115 51,8 222 100 4 % 128 49 133 51 261 100 5 % 61 60,4 40 39,6 101 100 total % 561 55 459 45 1020 100 Table 8: Allocation of turns. 6.4. Questionnaire results on teacher talking time The answers from the questionnaires with regards to TTT are represented in Table 9. The percentage shares of TTT in the lessons are included in the last column to enable the comparison between perceived, desired, and measured TTT. There are five more visualisations on TTT results in the Appendix: first and second, Figures 5 and 6 are bar charts on DPD per lesson from the teacher’s and the students’ perspectives. Although the bare number of data is very low, Table 17 provides the correlation coefficients between perceived and actually measured talking times. Table 18 has a grouped overview of how many students expressed a strong wish for the teacher to talk less and how many were rather content. Lastly, Table 19 provides a detailed individual breakdown of the students’ assessment of TTT. lesson p teacher d DPD p students d DPD % TTT 1 2 3 4 5 4 5 5 4 3 2 2 2 2 3 2 3 3 2 0 4,7 4,8 4,2 4,6 4,5 4 4,2 4 4,1 4 0,7 0,6 0,2 0,5 0,5 33,8 39,9 34,2 22,5 19,3 total 4,2 2,2 2 4,6 4,1 0,5 28,7 Table 9: Perception (p) and desire (d) for TTT and its difference (DPD). Value range: 1-6. Positive DPD denotes wish for less, negative value for more TTT. Zero: perception meets desire. 31 From the teacher’s point of view, perceived TTT is almost always in the upper half of the scale, ranging from 3 to 5. Her desired TTT is 2 in the first four lessons and 3 in the last one. The students, on the other side, perceived TTT to be between 4,2 and 4,8. They desired it to be in a range from 4 to 4,2. The values of DPD for TTT were almost always positive, i.e. the participants felt it was too high. From the teacher’s perspective, DPD ranges between 0 and 3. The mean is 2. Overall, the teacher was perfectly content with her own talking time in lesson five while she wished to have talked less in all other lessons. From the students’ point of view, DPD per lesson ranges from 0,2 to 0,7 with a mean of 0,5. 6.5. Questionnaire results on student talking time The answers from the questionnaires relating to STT are represented in Table 10. Here too, there are four more visual representations on STT in the Appendix: Figures 7 and 8 are bar charts with a per lesson overview of the teacher’s and the students’ DPD. Table 20 provides a grouped overview of how many students were rather content with their own talking times or would have liked to talk more. Finally, a detailed personalised breakdown of the students’ perceived and desired values for their own talking times is included in Table 21. Perceived STT is mostly around the middle of the scale. From the teacher’s perspective, it spans from 3 in lesson two to 5 in the last three lessons. Desired STT is 6 in all five lessons. The pupils themselves perceived their talking time to be lower, values spread from 2,8 to 3,8. Their desired STT ranges from 4,5 to 4,9 with a mean of 4,6. lesson p teacher d DPD p students d DPD % STT+SSC 1 2 3 4 5 4 3 5 5 5 6 6 6 6 6 -2 -3 -1 -1 -1 2,8 3,7 3,8 3,8 3,7 4,5 4,7 4,9 4,5 4,6 -1,7 -1 -1,1 -0,7 -0,9 60,9 34,7 36,5 67,7 74,3 total 4,4 6 -1,6 3,6 4,6 -1 56,8 Table 10: Perception (p) and desire (d) for STT and its difference (DPD). Value range: 1-6. Positive DPD denotes wish for less, negative value for more STT. Zero: perception meets desire. The values of DPD for STT are the opposite of TTT, they are all negative, i.e. both groups wished that the students had spoken more. The teacher’s values have a rather wide spread 32 ranging from -3 to -1. The mean is -1,6. From the students’ point of view, the average values per lesson have a narrower range spanning from -1,7 to -0,7. The total mean is -1. 6.6. Questionnaire results on overall contentment The answers from the questionnaires on overall satisfaction are represented in Table 11. The DPDs of TTT and STT are provided in the table for reference. lesson contentment teacher students DPD TTT teacher students DPD STT teacher students 1 2 3 4 5 3 2 3 4 4 2,1 3 3,2 3,3 3,2 2 3 3 2 0 0,7 0,6 0,2 0,5 0,5 -2 -3 -1 -1 -1 -1,7 -1 -1,1 -0,7 -0,9 total 3,2 2,9 2 0,5 -1,6 -1 Table 11: Contentment with the lessons. Value range: 1-6. The teacher’s contentment spans from 2 to 4. The average is 3,2. The students’ satisfaction has a narrower range going from 2,1 to 3,3 with a mean of 2,9. 7. Discussion In the following, I am going to discuss the results of my case study. I will focus on particularly interesting aspects that are worth to be scrutinised. In contrast to the previous section, I will discuss the results from the questionnaire on talking times in the first two sections on TTT and STT to compare them with my measures. After this, I am going to consider silence, the question types, the turns and finally the overall contentment with the lessons. 7.1. Teacher talking time First, it seems appropriate to set the results in context. Generally, TTT is very low compared to almost all the other studies I quoted earlier on. Only the study by Enright (1984) as well as Hitotuzi (2005) and Kampa (2012) yielded similar or even lower results on TTT than my study. TTT was 5 % higher on the Gymnasium than it was on Kampa’s ISS. Since silences are almost the same in both studies, it is no surprise that combined student talk is 5 % higher in Kampa’s study. Based on the findings of Hitotuzi (2005) and the DESI study (Helmke et al. 33 2008), I expected TTT to be lower in a class with a higher competence. But this expectation was not confirmed. The importance of the methods used by the teacher will be discussed in the section on student talk. One of the questions asked in the introduction was whether teachers are able to correctly assess their own talking time. All of the teachers in the DESI study underestimated their own talking time (Helmke et al. 2008: 351-352). The comparison between perceived and actually measured TTT shows that this does not apply to the teacher in my study. She assessed her own talking time with 5 in the lessons with the highest values and with lower numbers down until 2 in those lessons where she spoke least. Her expertise to correctly estimate her own talking time seems to be fine-grained. This is also confirmed by a medium correlation coefficient of 0,52 between TTT and her perceived values (cf. Table 17 on p. 45). Asking the same question for the students, the answer has to be different, however: perceived TTT is very high in all lessons, with a very narrow range. If we sorted the lessons from highest to lowest TTT, the students’ ranking would not match the actual order: in lesson five, the actual value is lowest at 19 %, while the learners marked it as 4,5, whereas lesson three had 34 % and the students marked it with 4,2. Generally, the pupils’ ability to assess TTT seems to be rather undeveloped and they tend to exaggerate their teacher’s talk. Yet, this might also be due to other reasons, such as using their power to grade the teacher in an anonymous questionnaire. Table 19 (p. 48) shows that only a few students like Sharon, Shelly, Linda, and to a lesser degree, Timmy, are able to accurately assess their teacher’s talk. There is almost no correlation between their estimated and actual TTT, the overall correlation coefficient is 0,09 for the students. With regards to desired TTT, the most obvious result is that the DPD is positive for the students’ and the teacher’s values for all lessons except one. This means that both the teacher and the learners think that TTT is too high and want to see it reduced. Except for lesson five, the teacher always marked her desired talking time with a 2. Lesson five had the lowest TTT, which is probably why she was content with her own talking time, giving it a 3 for both perceived and desired teacher talk. The students’ values on desired TTT are much higher than the teacher’s. As their values of perceived TTT are higher, too, their DPD is lower than the teacher’s and averages close to zero. Although this could be understood as a general vote of satisfaction with TTT, a closer look at the grouped values in Table 18 (p. 48) shows that consensus is rare: if we take lesson one as example, we find that five students — which equals 30 % of the attendees — had a DPD below zero, expressing the wish that the teacher should talk more. On the other side of the scale, seven students, more than 40 %, had DPDs above zero, two even at values four 34 and five, indicating that they felt the teacher talked way too much. Patterns like this can be found for most lessons. In general, however, zero is always the most frequently chosen DPD value, which hints at a general satisfaction with TTT. 7.2. Student talking time If we only considered STT as student talk, the requirements by SenBWF (2008) for an equal share between teacher and student talk were fulfilled already. However, by adding SSC to it, combined student talk comes to about 57 % which is a significantly better value because the teacher can use the advantages of both: she is able to monitor and diagnose the students’ language competences during 28 % of lesson time when only one pupil at a time speaks. And she leaves 29 % of time for the learners to talk among themselves, try out new structures and experiment with the language in symmetrical communication which has to be organised by themselves. Most visibly, both the teachers and learners agree that student talk is too low and should be higher. Similar to the situation with TTT, the students’ DPD is closer to zero than the teachers’, i.e. they are more content with their actual talking time than the teacher. A look at Table 20 (p. 49) indicates more uniformity with regards to the learners’ desired talking times: there are only between one and three students per lesson who wish to have talked less. The overwhelming majority — between nine and 15 — had a DPD partly far below zero, which denotes a strong wish to have talked more in the given lesson. In contrast to TTT, the most selected value is not zero but -1 or -2 through all the lessons. This result is surprising given the adolescence of the learners and their average English competence. The teacher is not as skilful in correctly estimating the students’ talking time as she is with TTT: although she assigned the lessons with the highest and the lowest STT with the highest and lowest values in the questionnaire, her ranking for the other lessons does not fit to the measures. The correlation coefficient between STT and her perceived value is 0,47 (cf. Table 17 on p. 45). This also applies to her overall ranking of the students’ total talking time during all the five lessons. As can be seen in Table 12 (p. 43), she has a clear idea on who speaks how much, but some of her guesses are quite far off. The students’ values are even more far off. Strictly speaking, the students’ estimate for their own talking time is an individual value and can therefore not be used as an assessment of the group’s overall talking time. But as an accumulated and averaged value it should provide an idea of student talking time. Yet it does not, and there are two reasons for this. For one thing, one half of combined STT is usually spent with SSC, which cannot be considered in my evaluation of talking times. There is the possibility that otherwise shy students 35 speak a lot during SSC phases and mark their talking time as high in the questionnaire. However, my observations suggest the opposite: strong and talkative learners speak more than shy students. For another, the learners are no experts in determining their own talking time. Table 21 (p. 49) shows that Eric, Craig and Kyle marked boxes 3, 4, and 6, although they had not said anything at all in the respective lessons. Only very few students, such as Annie and Wendy, are able to estimate their own talking times correctly, at least in relation to the previous and the following lessons. The students’ overall correlation coefficient between STT and their perceived values is 0,08 which means there is basically no correlation. The most interesting lessons are four and five. They had the highest amount of combined student talk, 68 % and 74 %, respectively. This is due to the methods that were used. Lesson four is especially high on STT with a share of over 38 %; this is due to the six thinking hats method, which enabled a long streak of complex student utterances that were also much longer than average learner turns. Lesson five, on the other hand, has the highest share of SSC with over 61 %, which is also due to the methods used. First, the preparation and carrying out of the gallery walk, which took about 40 minutes. And secondly, because the students started to solve a task in groups, although it was given to them individually — which was then coded as SSC and not silence any more — and the teacher encouraged this behaviour. 7.3. Silence Another interesting aspect is silence: it comes to 15 % in my study, has the same value in Kampa’s (2012) study and is slightly lower in the intermediate group of Hitotuzi (2005). However, the elementary group of Hitotuzi (ibid.), Inamullah, Hussain, and Din (2008), and Helmke et al. (2008) had double this value which raises the question why this is the case. One answer could be that the waiting times of those teachers were much longer. Another, more likely possibility are different teaching methods, e.g. when a lot of time is spent with writing down notes on the blackboard which are then copied by the students. This happened a lot in lesson two, when the teacher corrected the homework which many of the learners had not done at home: because she wanted them to write down their ideas on the blackboard themselves, there were almost 19 minutes of silence in this lesson. This teacher-centred approach also accounts for the highest amount of TTT observed in all five lessons, almost 40 %. 36 7.4. Question types With regards to question types, the results are rather different from those by Hasan (2006). While he found about 97 % display and 3 % reasoning questions asked by the teachers, the relations were quite different in this study. Although display questions hold the biggest share with over 40 %, this is in no way comparable to his values. The share of the other to types of questions is more evenly balanced with 26 % and 33 %. The high amount of referential and reasoning questions in lessons two and three is due to their topics: the class was dealing with a novel and the teacher often asked questions concerning the learner’s understanding and interpretation of the novel’s characters. The number of student questions and initiatives was higher than in Hasan’s (ibid.: 13) study. Student questions were requests for a clarification with regard to a task or a vocabulary item to be used. There were only ten student initiatives for instance when a learner contributed something to class without a preceding question from the teacher. This shows that the learners felt that the discourse was lacking this information and that they did not hesitate to take control of the discourse in at least a few rare instances. The even spread of all three kinds of questions suggests a high proportion of authentic communication, as the teacher is not only asking for things to which she knows the answers already, but gives the learners the possibility to reference information known only to them or to give an account of their personal opinion. Although one would suspect that student turns are longer in lessons with more reasoning question, this does not hold true: the average length of student turns in lessons two and three is 11,7 and 8 seconds, respectively, which is considerably lower than the average values for lessons four and five which is 15 seconds. This leads to the conclusion that teacher questions, although an important marker for classroom communication, need not necessarily be the most important factor influencing the length of learner contributions, but methods and self-governed phases of student talk might be more important as we shall see in the next section. 7.5. Turns Although TTT is only taking up a third of total talking time in the classroom, the teacher still holds a majority of turns with 55 %. This is an indicator for two things: on the one hand, that the teacher is dominating the discourse; and on the other, that her turns are shorter on average than the learners’ (cf. Table 16 on p. 45 for a detailed overview of average turn length). 37 Although I did not count and categorise the types of exchanges in my study, my impression is that the IRF exchange was a re-occurring, dominating pattern. Yet, the teacher often used the feedback turn as a new initiation turn so that the classic three-step pattern was not too visible. Lessons three and four are especially interesting: here, it was not the teacher, but the students who held the majority of turns at about 51 % per lesson. Usually, one turn by the teacher is followed by a student turn, then the teacher again, and so forth. Deviating from this pattern, the teacher let the students discuss among themselves in a fish bowl in lesson three. In lesson four, the pupils discussed their results from the six thinking hats method undisturbed by the teacher in the whole class. These episodes of discussions were sometimes as long as 17 turns, student after student, without any interruptions by the teacher. One such sequence is reprinted in Figure 2. However, it also needs to be noted, that the strong and talkative students were the most active in these phases. Another interesting result is the share of active and silent pupils per lesson. Haß (2006: 96) quotes studies that found up to 30 % of learners to be silent for a whole lesson. This cannot be confirmed in this class, as the findings in Table 14 (p. 44) show. Although there were up to three learners silent in three lessons, there were two lessons when every pupil took at least one turn in whole-class activities; SSC phases were not considered in this calculation. On average, 91 % of learners spoke every lesson. 7.6. Contentment The values on overall satisfaction are in a very narrow range. While the teacher’s contentment was just above the middle of the scale, the students’ was just below. Interestingly, the teacher’s was highest in those lessons where combined student talk was highest. This can be explained with the teacher’s wish to activate the learners as much as possible. Because we cannot simply assume that TTT or STT were evenly important for the students in their assessment of overall contentment, interpretation of their results is harder. However, their satisfaction was highest for lesson four, where DPD for STT was closest to zero, i.e. the students were most content with their own talking time. Other than that, the results from the student questionnaires do not allow any straightforward conclusion from their satisfaction with a lesson to talking times, but were most likely influenced by the methods used and other external factors that cannot be discussed here. 38 8. Conclusion In the course of this paper I have tried to answer several questions with regards to teacher and student talk in the English classroom. An investigation of previous studies on talking times in language classrooms uncovered that TTT has mostly been found to be higher than 60 %, although there are recent results that point into a different direction with values between 15 % and 44 %. By looking at various different teaching approaches, I approached the question on the right balance of teacher and student talk from various sides: pro teacher talk methodologies aim for teacher talk mainly and do not conceptualise student talk as more than a simple means to answer teacher questions. They agree with pro student talk approaches that teacher talk is an important source of language input for students which should not be banned from language lessons. Pro student talk approaches on the other side emphasise the importance of learner talk for the active construction of linguistic competence. There can be no uniform answer to the right balance of teacher and student talk, but it strongly depends on the skill to be trained in the specific lesson and the learners’ competence. After evaluating the benefits and drawbacks of teacher and student talk, I suggested a guide value of at least 50 % of student talk as orientation to grant learners enough time to try out and use English in the classroom. It is not enough to simply maximise STT, there should always be a significant part of symmetrical communication in SSC phases, too. I answered my primary research question How much do teachers talk in German EFL classrooms? by doing a case study with a young trainee teacher and found promising results: her talking time was as low as 29 % while the learners had 28 % of individual talking time and 29 % of SSC at their disposal. Somewhat surprisingly, TTT is higher in this Gymnasium than in the ISS case study of Kampa (2012). Another unexpected result was that almost all of the pupils in this class wanted to speak more and wanted their teacher to talk less. Another focus was the participants’ ability to estimate the amount of talk. While the teacher is very good at assessing her own talking time, she is less able to do so with the students’ talking time. She only has a rough overview of the learners’ individual oral contributions. The students overestimate their teacher’s talking time and underestimate their own talking time as a group. On an individual basis, their assessments are mostly erratic. An analysis of question types used by the teacher shows that she is using more reasoning and referential questions than teachers in other studies. Also, student questions and initiatives are more frequent than in other studies, though still rather rare. 39 In my theoretical and empirical investigations I came across a few shortcomings in the field that I want to mention briefly. First, it is surprising, that the importance of student talk in combination with meaningful and authentic communication took so long to be introduced to teacher training. Language teaching has been a profession for quite some time before communicative language teaching introduced its principles into the practice of language teachers. Secondly, many empirical studies present their results in idiosyncratic and particular ways, for instance by removing all silences from their data. This creates unnecessary difficulties when it comes to comparability with other studies. Finally, there are no recent large-scale studies on classroom communication — except for DESI. However, my study shows that having a researcher in the classroom actually makes teachers aware of talking time as an important aspect of language teaching. It is safe to assume that more research and publications on teacher and student talking time would keep the discourse going and eventually get more teachers to try to reduce their own and maximise their students’ talking time. I hope that this thesis provides a small contribution to this discourse and influences not only the teacher whom I studied, but also my own teaching in the future. 40 A. Appendix A.1. Questionnaires Schüler*innen-Fragebogen Nummer: Liebe Schüler*in, in diesem Fragebogen dürfen Sie anonym Ihre Meinung äußern. Bitte geben Sie an, wieviel Sie selbst in der soeben vergangenen Stunde gesprochen haben, und ob Sie gerne mehr oder weniger gesprochen hätten. Im zweiten Teil kreuzen Sie bitte an, wieviel nach Ihrem Gefühl Ihre Lehrerin in der letzten Stunde gesprochen hat, und ob Sie gerne hätten, dass sie mehr oder weniger spricht. Bitte denken Sie daran, dass es nur um die soeben vergangene Stunde geht! Vielen Dank für Ihre Mitarbeit! 1. Wie viel Englisch haben Sie in dieser Stunde gesprochen? gar nicht sehr viel 2. Wie viel Englisch hätten Sie in dieser Stunde gerne gesprochen? gar nicht sehr viel 3. Wie viel Englisch hat die Lehrerin in dieser Stunde gesprochen? gar nicht sehr viel 4. Wie viel Englisch hätte die Lehrerin in dieser Stunde sprechen sollen? gar nicht sehr viel 5. Wie hat Ihnen diese Englischstunde gefallen? gar nicht sehr gut 6. Kommentar zu: meinem Redeanteil dem Redeanteil der Lehrerin: Figure 3: Student questionnaire. 41 Lehrer*innen-Fragebogen Liebe Kollegin, in diesem Fragebogen dürfen Sie anonym Ihre Meinung äußern. Bitte geben Sie an, wieviel Sie selbst in der soeben vergangenen Stunde gesprochen haben, und ob Sie gerne mehr oder weniger gesprochen hätten. Im zweiten Teil kreuzen Sie bitte an, wieviel nach Ihrem Gefühl die Schüler*innen in der letzten Stunde gesprochen haben, und ob Sie gerne hätten, dass sie mehr oder weniger sprechen. Bitte denken Sie daran, dass es nur um die soeben vergangene Stunde geht! Vielen Dank für Ihre Mitarbeit! 1. Wie viel Englisch haben Sie in dieser Stunde gesprochen? gar nicht sehr viel 2. Wie viel Englisch hätten Sie in dieser Stunde gerne gesprochen? gar nicht sehr viel 3. Wie viel Englisch haben die Schüler*innen in dieser Stunde gesprochen? gar nicht sehr viel 4. Wie viel Englisch hätten die Schüler*innen in dieser Stunde sprechen sollen? gar nicht sehr viel 5. Wie hat Ihnen diese Englischstunde gefallen? gar nicht sehr gut 6. Kommentar zu: meinem Redeanteil den Redeanteilen der Schüler*innen: Figure 4: Teacher questionnaire. 42 A.2. Additional results A.2.1. Talking times student talking time actual ranking teacher ranking Shelly Annie Timmy Linda Stan Sharon Bertha Sheila Wendy Marcy Randolph Victoria Bebe Eric Craig Kyle Carol Clyde Bradley Kenny Liane 11:21 09:01 08:04 06:28 06:09 06:00 05:11 04:14 03:55 03:43 03:16 03:04 02:58 02:23 01:44 01:33 00:44 00:43 00:22 00:13 00:09 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 5 2 4 3 7 14 13 11 19 8 9 18 12 16 6 10 20 21 17 15 Table 12: Overall student talking times and teacher ranking. Values in bold match the actual ranking, or are very close to actual position. All names are pseudonyms. 43 lesson talking time TTT STT SSC 1 2 3 4 5 42:52 55:07 31:49 1:19:45 1:13:06 15:17 29:29 15:23 19:52 15:04 8:19 23:33 15:23 34:00 10:31 19:16 2:05 1:03 25:53 47:31 total % 4:42:39 100 1:35:05 33,6 1:31:46 32,5 1:35:48 33,9 STT+SSC 27:35 25:38 16:26 59:53 58:02 3:07:34 66,4 Table 13: Teacher and student talking times in h:mm:ss without silence. lesson attending active % silent % 1 2 3 4 5 17 16 18 18 17 14 16 16 18 14 82,4 100 88,9 100 82,4 3 0 2 0 3 17,6 0 11,1 0 17,6 Ø 17,2 15,6 90,7 1,6 9,3 Table 14: Share of active and silent students per lesson. Active means at least one turn during whole-class work. SSC phases are not considered. Ø = mean. A.2.2. Question types lesson display referential reasoning 1 2 3 4 5 5 39 13 5 12 10 9 8 18 3 5 24 15 12 5 total % 74 40,4 48 26,2 61 33,3 total 20 72 36 35 20 183 100 Table 15: Question types asked by the teacher, without student initiatives. 44 A.2.3. Turns participant lesson 1 STT t lesson 2 STT t lesson 3 STT t lesson 4 STT t lesson 5 STT t turns total Ø Shelly Annie Timmy Sharon Victoria Stan Bertha Linda Randolph Marcy Sheila Wendy Craig Bebe Kyle Eric Clyde Carol Bradley Kenny Liane 0:51 0:58 0:17 0:15 0:23 1:13 0:00 1:34 0:08 1:43 0:00 0:06 0:10 0:25 0:04 0:00 0:12 - 11 6 1 2 3 1 0 6 1 5 0 3 2 2 2 0 3 - 5:28 3:43 1:14 2:45 0:47 1:28 1:58 2:09 0:35 1:49 0:12 0:20 0:20 0:03 0:32 0:10 - 20 19 10 13 6 6 10 9 4 9 2 5 4 1 3 2 - 1:54 0:54 1:49 0:38 1:42 2:00 1:18 0:35 0:44 0:50 0:02 0:28 0:43 0:00 1:21 0:12 0:00 0:13 - 20 9 7 5 13 11 10 4 8 8 1 7 3 0 5 2 0 2 - 3:08 3:26 4:44 2:37 0:20 2:18 0:42 3:44 0:58 2:18 2:17 2:10 1:04 1:49 1:03 0:34 0:39 0:09 13 11 17 13 2 7 5 11 9 5 6 10 7 3 6 2 5 1 1:47 1:25 0:47 0:20 1:37 1:05 0:32 0:41 0:32 0:32 0:00 0:40 0:00 0:02 0:12 0:19 0:00 - 6 5 3 1 7 2 3 3 3 2 0 2 0 1 1 1 0 - 70 50 38 32 30 29 29 27 26 19 16 16 16 14 14 10 8 6 6 2 1 0:11 0:13 0:14 0:12 0:09 0:15 0:12 0:16 0:09 0:13 0:16 0:15 0:07 0:13 0:09 0:14 0:06 0:09 0:07 0:07 0:09 total 8:19 48 23:33 123 15:23 115 34:00 133 10:31 40 459 0:12 teacher 15:17 68 29:29 197 15:23 107 19:52 128 15:04 61 561 0:10 Table 16: Individual turns per lesson and average turn length (Ø). t = turns. Dash denotes absent student. All names are pseudonyms. A.2.4. Questionnaire results lesson STT students teacher TTT students teacher 1 2 3 4 5 0,175 -0,008 0,278 -0,238 0,135 - <0,001 <0,001 <0,001 <0,001 <0,001 - overall 0,079 0,470 0,093 0,521 Table 17: Correlation coefficient (Pearson’s r) between perceived and actually measured talking time. 45 Figure 5: The teacher’s perceived and desired TTT. Figure 6: The students’ perceived and desired TTT. 46 Figure 7: The teacher’s perceived and desired STT. Figure 8: The students’ perceived and desired STT. 47 lesson 1 2 3 4 5 4/5 2/3 1 2 0 0 1 1 3 3 2 1 3 2 4 4 3 0 DPD 0 -1 5 8 8 12 11 -2/-3 -4/-5 Ø % TTT 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0,7 0,6 0,2 0,5 0,5 33,8 39,9 34,2 22,5 19,3 4 1 4 1 2 Table 18: Difference of perception and desire for TTT; grouped values. Positive DPD denotes wish for less, negative value for more TTT. Ø = mean. student lesson 1 p d lesson 2 p d lesson 3 p d lesson 4 p d lesson 5 p d Stan Kyle Wendy Bebe Sharon Shelly Eric Kenny Randolph Sheila Liane Timmy Carol Bradley Linda Victoria Bertha Annie Clyde Craig Marcy 6 6 6 5 2 6 5 2 3 3 6 3 5 6 6 6 4 - 6 6 5 4 4 6 3 5 4 6 4 5 6 5 2 6 5 6 3 6 3 3 6 6 5 4 4 4 3 3 3 4 2 6 6 6 5 6 3 2 6 5 4 5 4 3 3 4 5 6 4 6 6 6 2 3 6 6 5 3 4 6 2 3 5 5 5 4 6 TTT 33,8 % 6 6 3 5 3 6 4 4 4 4 4 4 5 4 2 1 3 - 6 6 5 3 3 6 3 3 4 4 3 5 5 2 3 6 39,9 % 5 6 2 6 2 3 6 5 6 4 4 2 2 4 4 2 3 6 34,2 % 6 6 4 6 3 2 6 5 4 5 4 2 4 4 2 1 3 6 22,5 % 6 6 2 3 6 6 6 3 4 4 2 4 3 2 1 4 6 19,3 % Table 19: The students’ perceived and desired TTT; individually and per lesson. p = perceived TTT, d = desired TTT. Dash denotes absent student. All names are pseudonyms. 48 lesson 1 2 3 4 5 4/5 2/3 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 2 1 3 1 2 DPD 0 -1 0 5 4 2 6 -2/-3 -4/-5 Ø % STT 7 3 4 5 6 2 1 2 0 0 -1,7 -1 -1,1 -0,7 -0,9 18,4 31,9 34,2 38,4 13,5 6 6 5 8 3 Table 20: Difference of perception and desire for STT; grouped values. Positive DPD denotes wish for less, negative value for more STT. Ø = mean. student lesson 1 STT p d lesson 2 STT p d lesson 3 STT p d lesson 4 STT p d lesson 5 STT p d total Shelly Annie Timmy Linda Stan Sharon Bertha Sheila Wendy Marcy Randolph Victoria Bebe Eric Craig Kyle Carol Clyde Bradley Kenny Liane 0:51 0:58 0:17 0:00 0:23 1:13 0:08 1:43 1:34 0:15 0:06 0:25 0:00 0:10 0:00 0:04 0:12 - 5:28 3:43 1:14 2:09 1:28 2:45 1:58 1:49 0:35 0:47 0:20 0:03 0:12 0:20 0:32 0:10 - 1:54 0:54 1:49 0:35 2:00 0:38 1:18 0:02 0:50 0:44 1:42 0:43 1:21 0:28 0:00 0:12 0:00 0:13 - 3:08 3:26 4:44 3:44 2:18 2:37 0:42 2:17 2:10 2:18 0:58 0:20 1:49 0:34 1:04 1:03 0:39 0:09 1:47 1:25 0:47 0:41 1:05 0:20 0:32 0:32 0:32 1:37 0:00 0:00 0:40 0:12 0:02 0:19 0:00 - 11:21 9:01 8:04 6:28 6:09 6:00 5:11 4:14 3:55 3:43 3:16 3:04 2:58 2:23 1:44 1:33 0:44 0:43 0:22 0:13 0:09 STT 15:17 3 2 4 2 5 2 0 3 4 3 2 5 3 5 2 1 2 - 5 5 5 5 6 1 4 5 5 5 4 6 2 6 3 6 4 - 29:29 3 5 2 5 5 3 3 3 5 4 4 5 3 6 2 1 - 5 6 6 5 6 5 2 3 6 4 5 6 3 6 3 4 - 15:23 4 2 4 5 6 3 4 1 5 5 5 2 3 3 6 5 1 5 - 5 4 6 5 6 5 5 5 6 4 5 3 6 2 6 6 5 4 - 19:52 3 5 4 3 5 2 5 1 3 3 6 2 4 4 3 6 6 4 5 6 5 5 6 5 3 2 4 6 5 3 5 6 4 6 1 4 15:04 5 2 4 3 5 2 2 3 5 4 4 3 5 4 3 4 5 - 5 5 6 5 6 4 2 6 4 4 4 2 5 4 5 5 6 - 1:35:05 Table 21: The students’ actual, perceived, and desired talking times per lesson. p = perceived individual STT, d = desired individual STT. Dash denotes absent student. All names are pseudonyms. 49 Bibliography Albert, Ruth and Nicole Marx (2010): Empirisches Arbeiten in Linguistik und Sprachlehrforschung. Anleitung zu quantitativen Studien von der Planungsphase bis zum Forschungsbericht. Tübingen: Narr. Beck, Bärbel, Svenja Bundt, and Jens Gomolka (2008): “Ziele und Anlage der DESI-Studie”. In: Unterricht und Kompetenzerwerb in Deutsch und Englisch: Ergebnisse der DESI-Studie. Ed. by Eckhard Klieme. Weinheim & Basel: Beltz, pp. 11–25. Bellack, Arno A., Herbert M. Kliebard, Ronald T. Hyman, and Frank L. Smith (1966): The language of the classroom. New York: Teachers College Press. Bialystok, Ellen, Maria Fröhlich, and Joan Howard (1978): The teaching and learning of French as a second language in two distinct learning settings. Project report. Toronto: Modern Language Centre, Ontario Institute for Studies in Education. Breen, Michael P. and Christopher N. Candlin (2001): “The essentials of a communicative curriculum in language teaching.” In: Innovation in English Language Teaching. A reader. Ed. by David R. Hall and Ann Hewings. London: Routledge, pp. 9–26. Candlin, Christopher N. and Neil Mercer, eds. (2001): English Language Teaching in its social context. A reader. London: Routledge. Cazden, Courtney B. (1986): “Classroom discourse”. In: Handbook of Research on Teaching. Ed. by Merlin C. Wittrock. 3rd ed. New York: Macmillan, pp. 432–463. Chaudron, Craig (1988): Second Language Classrooms. Research on teaching and learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dellar, Hugh (2004): Putting our words to work: Rethinking Teacher Talking Time. url: http://web.archive.org/web/20110123064614/http://www.tesolspain.org/newsletter/hughdellar.html (visited on Oct. 21, 2015). Dunkin, Michael J. and Bruce J. Biddle (1974): The study of teaching. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. 50 Edwards, A.D. and D.P.G. Westgate (1994): Investigating Classroom Talk. 2nd ed. London: The Falmer Press. Enright, Scott D. (1984): “The organization of interaction in elementary classrooms”. In: On TESOL ’83: the question of control. Ed. by Jean Handscombe, Richard A. Orem, and Barry P. Taylor. Washington D.C.: TESOL, pp. 23–38. Gattegno, Caleb (1972): Teaching foreign languages in schools the Silent Way. New York: Educational Solutions. Grimm, Nancy, Michael Meyer, and Laurenz Volkmann (2015): Teaching English. Tübingen: Narr Francke Attempto. Hasan, Ali (2006): “Analysing Bilingual Classroom Discourse”. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 9 (1), pp. 7–18. Haß, Frank (2006): Fachdidaktik Englisch. Stuttgart: Klett. Hattie, John (2009): Visible Learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. London: Routledge. Helmke, Tuyet, Andreas Helmke, Friedrich-Wilhelm Schrader, Wolfgang Wagner, Günter Nold, and Konrad Schröder (2008): “Die Videostudie des Englischunterrichts”. In: Unterricht und Kompetenzerwerb in Deutsch und Englisch: Ergebnisse der DESI-Studie. Ed. by Eckhard Klieme. Weinheim & Basel: Beltz, pp. 345–363. Hitotuzi, Nilton (2005): “Teacher Talking Time in the EFL Classroom”. Profile: Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development 6, pp. 97–106. Inamullah, Hafiz Muhammad, Ishtiaq Hussain, and M. Nasseer Ud Din (2008): “Teacher-Students Verbal Interaction at the Secondary Level”. Journal of College Teaching & Learning 5 (9), pp. 41–44. Kampa, S. (2012): “Speaking for Contentment. Student and Teacher Talking Time in the EFL Classroom: A Case Study”. Unpublished master’s thesis. Freie Universität Berlin. Zentrum für Lehrerbildung. 51 Klieme, Eckhard, ed. (2008): Unterricht und Kompetenzerwerb in Deutsch und Englisch: Ergebnisse der DESI-Studie. Weinheim & Basel: Beltz. Klinzing, Hans Gerhard and Gisela Klinzing-Eurich (1988): “Questions, Responses, and Reactions”. In: Questioning and discussion: a multidisciplinary study. Ed. by J. T. Dillon. Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex, pp. 212–239. Knight, Paul (2001): “The development of EFL methodology”. In: English Language Teaching in its social context. A reader. Ed. by Christopher N. Candlin and Neil Mercer. London: Routledge, pp. 147–166. Krashen, Stephen D. and Tracy D. Terrell (1983): The Natural Approach. Language Acquisition in the Classroom. Oxford: Pergamon. Legarreta, Dorothy (1977): “Language Choice in Bilingual Classrooms”. TESOL Quarterly 11 (1), pp. 9–16. Müller-Hartmann, Andreas and Marita Schocker-von Ditfurth (2004): Introduction to English Language Teaching. Stuttgart: Klett. Ramirez, J. David, Sandra D. Yuen, Dena R. Ramey, and Barbara Merino (1986): First year report: longitudinal study of immersion programs for language minority children. Arlington, Va: SRA Technologies. Richards, Jack C. and Theodore S. Rodgers (1986): Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Schönwälder, Hans-Georg (1988): “Die Arbeitssituation der Lehrer als Bestimmungsfaktor der Arbeitssituation der Schüler”. In: Schulstreß Schülerstreß Elternstreß. Ed. by Jörg Berndt, Dirk Busch, and Hans-Georg Schönwälder. Bremen: Publikations-Service der Universität Bremen, pp. 97–130. Schwab, Götz (2009): Gesprächsanalyse und Fremdsprachenunterricht. Landau: Empirische Pädagogik. Seliger, Herbert (1977): “Does practice make perfect? A study of interaction pattern and L2 competence”. Language Learning 27 (2), pp. 263–278. 52 SenBJS – Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Sport Berlin (2006): Rahmenlehrplan für die Grundschule und die Sekundarstufe I Englisch. url: http://www.berlin.de/imperia/md/content/senbildung/unterricht/lehrplaene/sek1_englisch.pdf (visited on Feb. 14, 2016). SenBJW – Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Jugend und Wissenschaft (2015): Rahmenlehrplan Teil C. Moderne Fremdsprachen. Jahrgangsstufen 1-10. Berlin. url: http://bildungsserver.berlin-brandenburg.de/fileadmin/bbb/unterricht/ rahmenlehrplaene/Rahmenlehrplanprojekt/amtliche_Fassung/Teil_C_Mod_ Fremdsprachen_2015_11_16_web.pdf (visited on Feb. 14, 2016). SenBWF – Senatsverwaltung für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Forschung and Landesinstitut für Schule und Medien Brandenburg (2008): Fachbrief Nr. 1 Sprachförderung / Deutsch als Zweitsprache. Berlin: SenBWF and LISUM. url: http://bildungsserver.berlin-brandenburg.de/fileadmin/bbb/unterricht/ fachbriefe_berlin/sprachfoerderung/fachbrief_sprachfoerderung_daz_01.pdf (visited on Jan. 25, 2016). Sinclair, John McH. and R. Malcolm Coulthard (1975): Towards an Analysis of Discourse. The English used by teachers and pupils. London: Oxford University Press. Swann, Joann (2001): “Recording and transcribing talk in educational settings”. In: English Language Teaching in its social context. A reader. Ed. by Christopher N. Candlin and Neil Mercer. London: Routledge, pp. 323–344. Thornbury, Scott (1996): “Teachers research teacher talk”. ELT Journal 50 (4), pp. 279–289. Tsui Bik-May, Amy (1985): “Analyzing Input and Interaction in Second Language Classrooms”. RELC 16 (1) (June), pp. 8–30. van Lier, Leo (2001): “Constraints and resources in classroom talk: issues of equality and symmetry”. In: English Language Teaching in its social context. A reader. Ed. by Christopher N. Candlin and Neil Mercer. London: Routledge, pp. 90–107. Vygotsky, Lev Semenovich (1978): Mind in Society: the Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Ed. by Michael Cole, Vera John-Steiner, Sylvia Scribner, and Ellen Souberman. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 53 Walsh, Steve (2002): “Construction or obstruction: teacher talk and learner involvement in the EFL classroom”. Language Teaching Research 6 (1), pp. 3–23. Watzlawick, Paul, Janet Helmick Beavin, and Don D. Jackson (1968): Pragmatics of Human Communication. A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies, and Paradoxes. London: Faber and Faber. Williams, Jessica (2012): “Classroom research”. In: The handbook of second language acquisition. Ed. by Susan M. Gass and Alison Mackey. London: Routledge, pp. 541–554. 54