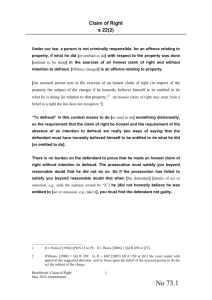

Criminal Law

Why do we criminalise certain conducts?

Devlin principle – criminal law should enforce morality vs Harm principle – behaviour don’t have to be

immoral before it is criminalised.

Legal elements of an offence:

Actus Reus =

physical element of an offence, e.g. killing, stealing, raping…

Mens Rea =

state of mind e.g. intention, recklessness…

AR + MR + ABSENCE OF A DEFENCE = CRIMINAL LIABILITY

(not all offences require MR =strict liability offences)

Burden of proof: on the prosecution

Standard of proof: beyond reasonable doubt.

ACTUS REAUS

The framework for criminal liability:

CAPACITY

CONDUCT

(AGE- MENTHAL

CAPACITY)

FAULT

(ACTUS REUS)

(MENS REA)

DEFENCES

(E.G. SELF

DEFENCE)

AR: is the conduct element of an offence, it must always be present and voluntary (includes failing to

act: OMISSIONS). There are conduct crimes and result crimes.

A conduct crime is where the conduct used is the offence, and there is no required result

element, e.g. theft: the conduct of taking someone else’s possession is the theft, there is no

required result such as the person realising etc.

A result crime is a crime which has a result element and is where a required result must happen

for the offence to be committed. An example is murder, if you attempt to murder but the

person does not die then you cannot be liable for murder, of course you would be liable for

other offences but since the other person did not die (the required result) there is no murder.

Result crimes need causation = CONDUCT + CONSEQUENCE

Omissions: there is no general duty to act for the benefit of someone else in England and Wales, R v

Miller [1983] 1 All ER 978, however there are situations which may give rise to a duty to act under

the common law

1. Special relationship

(doctor patient, parent child) R v Evans [2009] 1

WLR 1999 per Lord Judge “in some cases, such as those arising from a doctor/patient

relationship where the existence of the duty is not in dispute, the judge may well direct the

jury that a duty of care exists”. E.g. in R v Downes (1875) the parent didn’t call the doctor

letting the child die. No duty when a child reaches 18 Sheppard (1862), the age at that time

was 21.

2. Assumption of responsibility

R v Stone (1977) assumed responsibility for girl

suffering from anorexia when they took her into their home

3. Responsibility under contract: R v Pittwood (1902) a man may incur criminal liability from a

duty arising out of a contract

4. Responsibility under statute: a duty might arise under statute where Parliament has

included an omission to act within the definition of an offence e.g. failure to stop a RTA,

Health and Safety violations, wilfully neglecting child or spouse

5. Where the defendant creates a dangerous situation: R v Miller [1983] he creates a

dangerous situation and then he goes to sleep; R v Evans [2009] drug supply created a

dangerous situation and a duty to take reasonable steps to ensure safety.

6. If someone owns a piece of property and another person in his or her presence commits a

crime using that property, the owner is under the duty to seek to prevent the crime so far

as it is reasonable. See Rubie v Faulkner [1940] where the driving instructor was convicted

as an accessory after failing to prevent his pupil driving dangerously.

CAUSATION

Where the definition of the AR requires that certain consequences happen, the prosecution must prove

that it was the D’s conduct (by act or omission) that caused those things to happen.

Actus Reus = conduct + consequences

Some examples of offences where causation is required:

murder, manslaughter, “causing” or “inflicting” GBH, assault “occasioning” ABH (i.e. these are

consequences of the conduct). The prosecution must proof factual and legal causation.

Factual causation

defendant action must be the “but for” cause of result R v White

[1910] the act failed so no “but for” test. The defendant put poison in the victim’s drink, but she

died unrelatedly by heart attack, medical evidence suggested that she would have died at the same

way and time without drinking the poison

Legal causation

It is a principle established by judges that requires the defendant

act to be “operative and substantial” (in R v Smith [1959] the wound inflicted to the victim was

operating and substantial to the death of the victim) or “contribute significantly” to the result in R v

Pagett (1983) the deceased was held hostage

in front of the defendant; the act of the

policeman in firing back resulting in the

victim’s death was held reasonably

foreseeable considering the circumstances,

involuntary self defence did not break the

chain of causation.

Breaking the chain of causation: consider

causation as a chain: is there any intervening act

(novus actus interveniens: act or event that takes

over as the new “operative” cause) that breaks

the chain so as to remove D from responsibility?

Potential ways to break a chain of causation:

1. Voluntary interventions of third parties, R v Rafferty [2007] the defendant and his friends hit

the victim and then he run away while the others drawn the victim. It was held that his action

was not an operating and substantial cause to the death of the victim.

a. Does negligent medical treatment break the chain of causation? In R v Smith [1959] is

was held no as “but for the wound” the victim wouldn’t have needed medical care.

Consider R v Cheshire (1991). R v Jordan (1956) the original wound had been healed and

the doctor had administered an antibiotic to which the victim was allergic.

2. Acts of the victim themselves

in R v Kennedy (n.2) [2007] it was held that

the act of the victim of administering the drug voluntary was considered to break the chain of

causation.

i. “thin skull rule” = in R v Blue (1976) it was held that those who use violence on other

people must take their victims as they find them. The whole man not just the physical

man: with disease religion and whatsoever. in R v Hayward (1908) the defendant

shouted and assaulted her wife, which had a disease causing her to die, the court held

the defendant guilty even if an ordinary person wouldn’t have died under those

circumstances.

ii. In R v Roberts (1972) it was established that it should be considered if the actions of the

victim were a natural result of what the alleged assailant said or did, or if it was

something that could be reasonable foreseen as the consequence of what he said or did.

3. Natural events

in R v Gowans [2003] the defendant attacked a

delivery man who end up in coma, during the coma the victim suffered a serious infection which

lead to his death, it was held that even though the infection was not caused by the victim attack,

there was evidence showing that patient in coma were more likely to suffer the infection

therefor “but for” the coma the victim would have not suffer the infection so his conviction for

murder was sustained.

MENS REA

Mens Rea =

state of mind e.g. intention, recklessness negligence.

In criminal law a conduct alone should not be enough to criminalise a person, the blameworthiness of

the person should also be considered (not valid for strict liability offences).

To be able to criminalise a conduct the AR and MR must coincide, but the general principle has become

more flexible Fagan v MPC (1968). Once the defendant is aware of the danger but fails to mitigate it the

AR and MR coincide. Consider Miller [1983].

Transferred fault = if a person has a malicious intent towards one person, and in carrying that intent he

injures another man, the MR can be transferred R v Latimer (1886).

LEVELS OF CULPABILITY

INTENTION = sometimes intent is the essence of an offence and is a question for the jury to

answer applying the subjective test. Criminal Justice Act 1967 s.8

Direct Intention = the consequence was the aim of the Defendant if he acts with the

purpose of producing that consequence.

Oblique Intention = a virtually certain consequence of which the defendant was aware it

was virtually certain to occur. R v Hyam [1975]. In deciding whether the D had an oblique intention 2

questions must be answered by the jury R v Moloney [1985]:

1. Was the consequence a natural consequence of the defendant voluntary act?

2. Did the defendant foresee that consequence as being a natural consequence of his

act?

If the answer to both questions is yes, then the victim intended that consequence. In this case

the D killed his father while he was intoxicated, his defence was not the intoxication but the fact

that he lacked MR; his intoxication was evidence from which the jury concluded that he lacked

intent.

In R v Bunch [2013] the defendant, a very drunk man killed his wife, the nature of attack and the

level of force used in the stabbing pointed to an intention to kill, his drunkenness was not

relevant as at the time he acted with the intention to kill. “a drunken intent is still an intent”.

See R v Woollin [1998] for oblique intention.

RECKLESSNESS =

Subjective test R v Cunningham [1957]. a person acts recklessly with regard to result

when he is aware of a risk that it will occur, and it is in the circumstances known to him

unreasonable to take the risk. Whether the risk was a reasonable one to take is to be

decided by the standard of the ordinary and reasonable person. Irrelevant whether the D

thought it was reasonable or not.

The objective test MPC v Caldwell [1982] recklessness has been abolished since 2003 by

the HL. It was a test of reasonable person with no exception to children or state of mind,

or a person who realises that there is a risk but is convinced that no harm will occur.

In R v G and another [2003] the HL said that the previous test was capable of leading to

obvious unfairness, it is neither moral or just to convict a defendant (least of all a child)

on the strength of what someone else would have apprehended.

NEGLIGENCE = a person could be convicted under negligence if he behaves in a way contrary to

what a reasonable person with the skills and knowledge that he was supposed to have would

have done. If he is guilty of negligence, then he is liable R v Adomako [1995]

MURDER

The crime is committed where a person of sound mind unlawfully kills any human being (from the

moment a person is born till he is no longer a living person) under the Queen’s peace with malice

afterthought. If D rely on self -defence, then no offence has been committed. Attorney General

Reference [1998] if the child is injured in the womb and dies shortly after being born is still murder.

Murder is a result crime = D has to kill somebody, and the person must be dead. The prosecution must

prove over reasonable doubt that the defendant through his conduct caused the death of the V. ACTUS

REUS (D must do an act or omission) CONSEQUENCE (victim death)

Factual causation

defendant action must be the “but for” cause of

result R v White [1910] the act failed so no “but for” test. The defendant put poison in

the victim’s drink, but she died unrelatedly by heart attack, medical evidence suggested

that she would have died at the same way and time without drinking the poison

Legal causation

It is a principle established by judges that requires

the defendant act to be “operative and substantial” (in R v Smith [1959] the wound

inflicted to the victim was operating and substantial to the death of the victim) or

“contribute significantly” to the result (in R v Pagett (1983) the deceased was held

hostage in front of the defendant; the act of the policeman in firing back resulting in the

victim’s death was held reasonably foreseeable considering the circumstances),

involuntary self defence did not break the chain of causation.

MENS REAS = “with malice afterthought” an intention to kill or cause grievous bodily harm R v

Cunningham [1982].

What is grievous bodily harm? An intention to cause permanent injuries, multiple cuts wounds that

need hospitalizing. Grievous bodily harm could lead to attempted murder or GBH if the person does not

die. In this case the defendant attacked the victim in a pub believing (wrongly) that the victim had had

sexual relations with his fiancé. The defendant knocked him to the ground and repeatedly struck him on

the head with a bar stool. The victim suffered a fractured skull and a subdural haemorrhage from which

he died 7 days later. The jury convicted the defendant of murder having found that he intended really

serious harm at the time of the attack. The defendant appealed contending that the law of murder

should be confined to those who intend to kill and thus the decision in R v Vickers was wrongly decided.

The defendant relied upon dissenting judgment of Lord Diplock in Hyam.

Direct Intention = the death of the victim was the aim of the Defendant if he acts with

the purpose of producing that consequence.

Oblique Intention = a virtually certain consequence that the victim will die of which the

defendant was aware it was virtually certain to occur. R v Hyam [1975]. In deciding whether the D

had an oblique intention 2 questions must be answered by the jury R v Moloney [1985]:

3. Was the consequence a natural consequence of the defendant voluntary act?

4. Did the defendant foresee that consequence as being a natural consequence of his

voluntary act?

Oblique intention has to be distinguished by recklessness, in the former case the likeliness that death

would have been the consequence is higher than recklessness.

SENTENCE

The sentence for adults is mandatory life imprisonment (depriving the person’s liberty)

MANDATORY LIFE SENTENCE =

1. MINIMUM TERM set by the judge, although it could be:

life imprisonment for “exceptionally high seriousness” cases e.g. terrorist or multiple

murder, premeditated multiple murders, repeat offenders. Must be 21 yrs old

30 years for cases which are of “particularly high seriousness” including murder of police

officers, murders for gain e.g. rubbery murders involving guns explosives. Must be 18 yrs

15 years if neither of the two apply. Must be 18 years old

If over 10 years old but less than 18 starting point is 12 years.

2. IMPRISONMENT UNTIL RELEASE IS AUTHORISED the Parole Board decide whether a prisoner is

safe to release +

3. RELEASE ON LIFE SENTENCE if the licence condition is breached the offender can be returned to

custody.

ASSISTED SUICIDE is illegal under s2 of the SUICIDE ACT 1961 DPP v Pretty [2002]

VOLUNTARY MANSLAUGHTER

Voluntary manslaughter is when the defendant intended to kill or cause grievous bodily harm but there

are some circumstances that mitigate the offence of murder into manslaughter:

LOSS OF CONTROL (Coroners Act 2009 s.54) since October 2010 = it is a partial defence

only for murder, and that reduces the offence of murder into manslaughter.

Before there was the provocation defence and two questions were meant to be answered:

1. Did the provocation cause the defendant to lose his self-control?

2. Was the provocation such that a reasonable person would have acted similarly?

This was not fair to cases of sexual abuse as with this defence it was required that the defendant

acted in the heat of the moment whilst sexually abused people usually do not act suddenly. R v

Duffy 1949.

3 conditions must be satisfied now:

1. D loss of self-control = subjective test

S.54 (2) no requirement of suddenness, different from R v Duffy [1949] where the loss of

control had to be sudden and temporary;

S.54 (4) does not apply if D acted in revenge

S.55(6) defence is not available if D said or did something as to provide an excuse for the

violence and sexual infidelity is not valid anymore… see R v Clinton [2013] although

infidelity case there are other factor to be considered, the D wanted to commit suicide

and the V aggravated the circumstances by mocking him. See also R v Dawes [2013] the

D wanted to rely on the fact that the victim caused him to lose control by defending

himself, but the appeal was dismissed as he initiated the violence.

2. The loss of self-control had a qualifying trigger under s.55 of the CA 2009

Fear of serious violence from V against D or another identified person s.55 (3)

The loss of control was attributable to a thing said or done or both which was extremely

provocative

3. A person of D’s sex and age with a normal degree of tolerance and self-restrain and in

the circumstances of D might have reacted in the same or in similar way to D

S.54 is an objective test. DPP V Camplin [1978] added same age of the accused as it is

not fair to consider what a person of a different age would have apprehended (old head

on young shoulders). Although we do not consider what a drunken person would have

done Attorney general for Jersey v Holley [2005] or a person with mental illness. This is

a question for the jury

SENTENCE

DIMINISHED RESPONSIBILITY (Homicide Act 1957 s.2) is a partial defence to murder

only and there are 4 requirements that must be meet.

(1) A person (“D”) who kills or is a party to the killing of another is not to be convicted of murder

if D was suffering from an abnormality of mental functioning which…

Under the old law it was only necessary to prove an abnormality of mind R v Byrne [1960],

something that was not normal, with the new law the abnormality of mental functioning needs

to result from a recognised medical condition to protect the sanctity of life e.g. depression

consider R v Dowds [2012] he was an heavy drinker but not an alcoholic so he was not qualified

for the partial defense.

See R v Brennan [2014] The defence has to proof that DIMINISHED RESPONSIBILITY existed to

the balance of probabilities and the jury must consider this if it is not contested by the

prosecution.

Causation requirement

D’s conduct must be caused significantly by the mental impairment s(1B).

INVOLUNTARY MANSLAUGHTER

Involuntary manslaughter is when the defendant did not intend to kill the victim or cause GBH:

CONSTRUCTIVE/UNLAWFUL ACT MANSLAUGHTER

This type of manslaughter has been labelled as ‘constructive’ because the law constructs liability out of

the lesser crime that the defendant committed. E.g. pushing the victim with the intention of hurting

him, then V hits his head and dies; the defendant will not only be liable for doing the unlawful act, but

also for the consequence of the unlawful act.

It consists of the following elements:

1. An unlawful act = the unlawful act has to be a criminal act with corresponding Mens Rea

only for the unlawful act not the consequence of the V dying. R v Newbury [1977]. E.g.

MR only for the intention of frightening the victim

It has to be an unlawful act not a tort or a breach of contract. A failure to act or call for

help is not a crime R v Lowe [1973] except when the law requires to do so e.g. R v Stone

(1977)

2. Which is dangerous = the jury will decide the dangerousness of the act R v Church

[1966]. It is an objective test (no age or sex considered), if a reasonable person would

inevitable recognise the risk of serious harm

3. Which causes the death of the victim = R v Kennedy (n.2) [2007] the act of the

defendant must cause the death of the victim (legal + factual causation); in this case

there is a break in the chain of causation which means that the defendant is not liable

GROSS NEGLIGENCE MANSLAUGHTHER

Gross negligence manslaughter when the D fails to do something when the law requires him to do

something. See R v Adomako [1995] confirmed in R v Misra [2005]:

1. Was there a duty to care for the deceased?

2. Was that duty breached?

3. Did the breach of the duty caused the death of the victim?

REMEMBER FACTUAL AND LEGAL CAUSATION is there a break in the chain of causation?

4. Was the breach so grossly negligent to justify a criminal conviction? The jury would

decide if the breach was so grossly negligent.

NON-FATAL OFFENCES AGAINST THE PERSON

There are many different non-fatal offences against the person, many of which overlap with each other.

They cover sexual offences, assault, occasioning actual bodily harm, causing grievous bodily harm, racially

aggravated assaults, administering noxious substances, harassment and the list goes on. They involve

protecting the right to bodily integrity.

COMMON ASSAULT AND BATTERRY

These are two different offences.

Section 39 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 provides that:

“Common assault and battery shall be summary offences, triable in magistrate courts, and a

person guilty of either of them shall be liable to a fine not exceeding level 5 on the standard scale,

to imprisonment not exceeding six months or to both.”

1. COMMON ASSAULT = Causing the victim to apprehend immediate unlawful force; there

is no need of an actual action, just the V thinks that there is going to be a force against

him; the V does not need to be afraid.

AR = Causing the V to apprehend imminent unlawful force. Words can also amount to

assault, so does silence, see R v Ireland [1997], the defendant made silent calls to his

victims which made them apprehend immediate infliction of force. REMEMBER FACTUAL

AND LEGAL CAUSATION.

MR = Intention or recklessness (Cunningham subjective recklessness)

what is considered immediate or imminent? Must be a fear of imminent harm not an

imminent fear of a harm in the future. See R v Costanza [1997], the D sent over 800

messages, on 4 and 12 June the V received two letters which she perceived as threatening,

she feared that the D might harm her at some time not excluding the immediate future.

(could be in two minutes but also in a week)

2. BATTERY = inflicting unlawful force upon the body of another

AR = Any unlawful physical contact by D with the body of V. see R v Thomas [1985]

unwanted touching of the bottom of a girl’s skirt amounted to battery. Does not have to

be painful.

MR = Intention or recklessness (Cunningham subjective recklessness)

CPS Guidelines:

a) scratches and grazes

b) minor bruising and swellings

c) superficial cuts

d) a black eye

e) invasion of personal space

DPP V K (1990) no requirement of direct force, in this case the victim pored the acid into

the hand dryer. An act, to be unlawful, must fall outside of the category of ordinary

everyday contact Collins v Wilcock [1984]

ACTUAL BODILY HARM

s.47 Offences Against the Person Act 1861

“Whosoever shall be convicted upon an indictment of any assault occasioning actual bodily harm

shall be liable…term not exceeding five years...”Max. penalty is 5 years; triable either way (both

indictment and summarily by virtue of s. 19 Magistrates’ Court Act 1952).

AR - the D must commit an assault (broad sense) or a battery which causes the victim to suffer

actual bodily harm. REMEMBER FACTUAL AND LEGAL CAUSATION.

MR - intention or Cunningham recklessness. To be noted the D must only have the MR of the assault

or battery that leads to ABH no need to prove intent or recklessness with regard to causing ABH see

R v Savage [1992].

It must be shown that there was an assault (broad sense = common assault/battery), the D intended

or reckless about the assault, the V suffered ABH, the ABH was procured by the D assault. See R v

Roberts [1972], the D made indecent proposals to the woman in the car, the V frightened jumped out

of the car. The D assaulted the V, which caused her to jump and sustain ABH

WHAT DOES ACTUAL BODILY HARM MEAN? Not necessary permanent injuries, any injury calculated

to interfere the health and comfort of the victim, psychological injuries are also considered R v Ireland

[1997] CPS Charging Standards:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

temporary loss of sensory functions

extensive or multiple bruising

minor fractures

minor cuts requiring stitching

psychiatric treatment that is more than mere distress or panic R v Ireland [1997]

E.g. Alf sends bertha threatening text messages, following which Bertha suffers depression. Alf will be

charged with assault occasioning to actual bodily harm. The prosecution will rely on R v Ireland [1997]

to show that words can amount to assault and that depression can be regarded as actual bodily harm.

Although they may have to prove that:

1. Bertha apprehended an immediate use of force (not just afraid) R v Costanza 1997

2. Alf intended or foresaw that Bertha would apprehend imminent use of force

3. Bertha suffered the depression because of the apprehension of the use of force (ASSAULT)

GREVIOUS BODILY HARM

S.20 Offences Against the Person Act

“Whosoever shall unlawfully (LAWFUL = SELF DEFENCE/DURESS) and maliciously wound or inflict

any grievous bodily harm upon any other person, either with or without any weapon or

instrument, shall be guilty of a misdemeanour, and being convicted thereof shall be liable...to a

term not exceeding five years”

AR =WOUNDING – INFLICTING GREVIOUS BODILY HARM, requires a break in the continuity of

the skin (stubbing or cutting), no more or less than really serious harm (R v Smith [1961])

MR = “maliciously” intention or Cunningham recklessness but to what extent? Doesn’t matter if

the D doesn’t foresee that the unlawful act might cause physical harm, or the gravity described

in S.20 R v Mowatt [1967]

CPS Charging Standards:

a) injury amounting in permanent disability or permanent loss of sensory function

b) broken or displaced limbs such as fractured skull, compound fractures, broken

cheeks, jaws, ribs etc.

c) injuries which result in more than minor permanent disfigurement

d) injuries that cause a substantial loss of blood, usually necessitating a transfusion

e) injuries resulting in lengthy treatment or incapacity

f) psychiatric injury can amount to GBH R v Burstow [1997]

R v Bollom [2003] in accessing the seriousness of the injury, the jury should take into account the

impact of them on the particular victim.

S.18 OAPA

Wound/Cause GBH ‘with intent’

“Whosoever shall unlawfully and maliciously by any means whatsoever wound or cause any

grievous bodily harm to any person...with intent… to imprisonment for life”

AR =WOUNDING, requires a break in the continuity of the skin (stubbing or cutting) no more or

less than really serious harm (R v Smith [1961])

MR = “maliciously” intention to cause GBH not wound

Can consent be a valid defence to GBH?

Consent is valid only if it is informed, voluntary and given by someone who is competent.

Consent would not normally be a defence to ABH or GBH, but court has recognised exceptions

where the ABH or GBH is sustained during the course of the following accepted categories:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Sporting activities (implied consent to anything below a reckless foul)

Dangerous exhibitions and bravado

Rough and undisciplined horseplay

Surgery

Tattooing and body piercing R v Wilson (1996) the appeal was allowed as the GBH was caused

through tattooing and comes under the exceptions.

6. Religious flagellation

7. Infectious intimate relations R v Dica [2004] if the V agrees to have sexual relationship knowing

that the other person is infectious and therefore there is a risk of the disease to be transmitted

These exceptions were discussed in Brown [1994]. See also Emmett [1999] they were convicted

even though it was a heterosexual relationship. The injuries did not fell under the exceptions

and the danger involved was very high.

Should the transmission of HIV be criminalised?

R v Clarence (1888) he gave his wife the disease but because they were married he was not

convicted

R v Dica [2004] if the D gives the V a transferrable decease he could be criminally liable if he

intended or was reckless. If the V consent to the risk, it is a defence under S.20 of the Offences

Against the Person Act 1861

INCHOATE OFFENCES

Inchoate Offences only operate with the Principal offence which can also be referred as the

“substantive offence” or “full offence”, it doesn’t matter if the principal offence ever actually comes

about.

There is a PRINCIPAL OFFENCE which D is trying to:

1. ATTEMPT taking steps that are more than merely preparatory to the commission of the offence,

while intending to commit it.

CRIMINAL ATTEMPTS ACT 1981 S1(1) If, with intent to commit an offence to which this section

applies, a person does an act which is more than merely preparatory to the commission of the

offence, he is guilty of attempting to commit the offence. S4 the sentencing can be the same as the

principal offence, e.g. for manslaughter is 25 years, attempted manslaughter is 25 as well.

Only indictable offences are considered in this case (triable in the crown court with a jury).

Unlawful act manslaughter cannot be considered as D did not foresee death when committing the

unlawful act so cannot attempt to kill through unlawful act.

You cannot attempt to aid and abet or conspire, you have to do the offence, but it could be an

attempt under the Serious Crime Act 2007.

Legal impossibility You cannot attempt to commit an offence that is not a crime e.g. adultery. In

Taaffe [1983] the defendant thought that importing foreign currencies was an offence, but it was

not, so he could not be convicted.

Factual impossibility A person may be guilty of attempting to commit an offence even though the

facts are such that the commission of the offence is impossible e.g. you point an unloaded gun to

somebody, intending to kill, but you do not know that it is not loaded. You are still charged of

attempted murder because you would have killed the V if you had the chance. See Shivpuri [1987]

he confessed he was transporting illegal drugs even though they were harmless vegetables.

On the contrary if you knew that it was not loaded, in that case you cannot be charged of attempted

murder because you knew that you were not going to kill the V.

AR = Carrying out an act which is more than mere preparatory to the commission of an offence.

can you attempt by omission? Law Commission, Conspiracy and Attempt 2009 says yes.

If parent fails to feed a child (special relationship) with intent to kill but somebody feeds the child and

does not die, then parent is liable for attempted murder. REMEMBER FACTUAL AND LEGAL

CAUSATION.

What is more than preparatory? it was held in Jones [1990] that it should be given its natural

meaning. Useful tools to identify when the act is more than preparatory is “on the job” or “embarks

on the crime proper”. It is a question for the jury to answer if the judge is satisfied with the

evidence.

In Jones the D got in the back of a car where the V was in and pointed a gun at him, following a

struggle V escaped. D was charged with attempted murder even if he didn’t remove the safety

catch, put the finger on the trigger and pull it his acts were mere than preparatory.

In Gullefer [1990] the D placed a bet on a dog, and as he was losing he jumped on track to try and

stop the race and get his money back, he was charged with attempted theft, but the CA held that he

did not take steps that were more than merely preparatory, he still had to go to the bookies and

demand his money back (although at this stage it will not be attempted theft but theft).

In Campbell [1991] D was arrested outside the post office while intending to rob, carrying imitation

firearm and threatening note, he also confessed to planning the robbery, he was charged with

attempted robbery, but the CA held that he did not take steps that were more than merely

preparatory as he had not entered into the post office yet.

In Tosty [1997] the D was examining the lock of a barn and he had a car nearby containing metal

cutting equipment, he was charged with attempted burglary and the CA upheld his conviction

MR = intention (direct and indirect) to commit the principal offence e.g. for murder intention to kill

only not to cause grievous bodily harm, see Whybrow (1951). It has to be intention to commit the

crime not recklessness e.g. intention to cause GBH or ABH not recklessness even though is enough

for the full offence.

Conditional intention is also consider e.g. looking at somebody handbag with intention to steal if

there is something valuable, but the wording of the criminal charge needs to be considered

carefully. In Husseyn (1978) the defendant was charged with attempting to steal sub-aqua

equipment from a van, but the CA held that because it could not be said that he had intended to

take the equipment he could not be found guilty of attempting to steal it; the correct charge could

have been attempting to steal “some or all of the contents of the van” or “attempting to steal from

a van”.

Possible attempt Khan [1990] D and others attempted to rape the V. 2 elements to the MR:

Intention to penetrate the vigina with recklessness as to the consent of the victim could be

sufficient to convict.

Impossible attempt Pace and Rogers [2014] undercover police sold scrap metal to D intimating that

the metal was stolen (factual impossibility as the metal was not in fact stolen).

D charged with attempting to convert criminal property the CA held that he could not be convicted

because he only had the suspicion of the metal being stolen and suspicion was not enough, he had

to had intent for the metal to be stolen and moreover he could not be convicted because the metal

was not in fact stolen.

2. ASSIST/ENCOURAGE another to commit an offence (even if they do not do so)

3. CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY two or more people agreeing to pursue a course of conduct which

involves committing an offence

COMPLICITY

Complicity is sometimes referred as the “accomplice liability”, “parties in crime”, “secondary

parties” and is regulated by the Accessories and Abettors Act 1861, s.8 which states that:

Whoever shall aid, abet, counsel, or procure (AR) the commission of any offence indictable shall be

liable to be tried, indicted and punished as the principal offender. For this act to be valid there must

be a principal offence.

Accomplice, does not complete the AR of the offence, but aids, abet, counsel procures P to do it,

which he commits the act with intended MR. He is liable for the same crime as the principal

offender and he must intend the principal offender to commit the offence.

You can be an accomplice by Joint Enterprise during which the principal commits a further offence

Principal offence this is the offence that the D is aiding, abetting, counselling, procuring somebody

else to commit. It is also referred as the “full offence” or “substantive offence”.

Principal offender is the party who commits the AR of the offence with required MR. There could

also be Joint principals which are multiple Ds that complete the AR with required MS e.g. Val and

Ruby stab Ian.

Principal via innocent agency where the AR is committed by an uninformed party, in this case D

remains liable as the Principal offender, the innocent party, did not have the required MR or was

insane or under the age of criminal responsibility. See Michael (1840) a parent wanted to kill her

child and put poison in the baby’s drink and told the nurse it was medicine, the nurse did not know

it was poison, but she did not administer the substance, later a child took the substance and

administered it, leading to the baby’s death. The mother was the principal offender via innocent

agency.

AR whoever shall aid, abet, counsel or procure. What does it mean? Attorney General Reference

(1975) says it should be given it ordinary meaning. D’s assistance must contribute in some way to

P’s offence and the encouragement must be communicated to P.

Factual difficulties: principal offender or an accomplice?

D’s role in the principal offence is unclear. In Gianetto [1997] as long as D2 either killed the V

himself or encouraged D1 to kill the V he could be held as an accomplice and be convicted of

murder as the principal offender.

If the evidence places the D at the scene but it cannot be proven that he committed the

offence, or he was an accomplice then he must be acquitted. If they were all involved then

they can be convicted as principal or accomplice, if we are not sure of their participation

they must all be acquitted (innocent until proven guilty).

1. Aiding offering help e.g. giving information, or a piece of equipment or driving P to the

scene Nedrick-Smith [2006] not necessary to show “but for” test. The act must aid P, so if

you give a knife and P decide to use a gun you did not aid but might be counselling.

2. Abetting encouraging, mere presence cannot be considered as abetting. In Clarkson [1971]

Two soldiers (the defendants) had entered a room following the noise from a disturbance

therein. They found some other soldiers raping a woman and remained on the scene to

watch what was happening. They were convicted of abetting the rapes and successfully

appealed on the basis that their mere presence alone could not have been sufficient for

liability. It was held that the jury should have been directed that there could only be a

conviction if (a) the presence of the defendant at the scene of the crime actually encouraged

its commission, and (b) the accused had intended their presence to offer such

encouragement.

If the person presence encourages the principal, then he is an Accessory but only if the

accomplice is aware that the principal is encouraged by his presence. See Tait [1993].

3. Counselling same meaning as abetting, encouraging. Could be nodding Gianetto [1997]

Could you counsel by omission? See Russell [1933] D does nothing while wife drowns the

child (omission) it was held yes because under special relationship.

4. Procure A G Ref (1975) D adds alcohol to P’s drink knowing P would drive home, P was then

charged with driving exceeding the alcohol level, D was liable as an accessory as he procured

P’s offence by endeavour.

5. Party to a joint enterprise arises where two or more people together embark on the

commission of a criminal offence (crime A), during which one of them goes on to commit a

further offence (crime B). Crime B must be committed during crime A.

In Gnango [2011] two men had a common intention to commit a crime, as an incident in

committing crime A the other defendant commits crime B, the other defendant is regarded

as an accomplice as he had foreseen the possibility that he might do so, there is no need to

show that the accomplice aided or abetted or procured or counselled.

In Gnango [2011] The gun fire was guilty of murder by virtue of transferred fault Latimer

[1886], but was the other man an accomplice? The court held that he was an accomplice.

MR In Jogee [2016] it was held that complicity liability requires the D to intend (not reckless) to assist

or encourage P to commit the offence; foresight of P committing the offence is not enough. Could be

direct and indirect intention.

The assistance must also be voluntary see Bryce [2004].

D must intend P to commit the offence with whatever MR is required for the act

D must know what the principal offence is but not necessary to know the details, he can be

convicted if a less serious crime come about but not if a more serious crime than what he

intended come about.

Can be constructive manslaughter as no foresight is required by P or D.

Defences

Withdrawal of assistance, encouragement. See O’ Flaherty [2004] court will measure the

assistance vs the action taken to withdraw. The withdrawal must take place before the principal

commits the offence.

The victim rule V cannot be an accomplice against themselves Tyrell [1984]

SEXUAL OFFENCES

There are around 50 offences considered as sexual offences. The harm caused to the victim can be

physical (vaginal/anal tearing, bruising, STI, unwanted pregnancy etc.) and psychological

(depression, trauma, vulnerability, anger, self-blame, guilt etc.).

People have the right to decide with whom they have sexual relations (Munro 2014), so even if you

have sex with an unconscious person and s/he does not suffer any physical or psychological harm it

is still considered as rape see Ciccarelli [2011].

Stranger rape: stranger to the V, violence and resistance form V

Acquaintance rape: someone know to the V (90% of victims knew their perpetrator 2012-2013

stats)

A person can be an accomplice to these three offences. In rape case a woman can be an accomplice

The Sexual Offences Act 2003 deals with all the sexual offences.

RAPE s.1

AR

1. Penile penetration of vagina, anus, or mouth and

2. Victim does not consent to penetration. {is this a case where it is presumed that the

victim did not consent? Is there an evidential presumption? Did the victim consented

under the basic meaning of s.74?

The act can only be done by a man (only a man has a penis), before 2003 it was only vagina

so only women were Victims, after 2003 anus and mouth were added to consider men as

well.

MR intention to penetrate vagina, anus, mouth (not recklessness) and no reasonable belief

in V’s consent (consider evidential presumption s.76 and 75). If the defendant believed that

the victim consented than he cannot be guilty of rape.

CONSIDERING NO REASONABLE BELIEF

See Morgan v DPP [1975] a man told three friends to go and have sex with his wife in a hotel

room, telling them to ignore her if she resists as she is “kinky”. At the time it was a subjective

test and no requirement of reasonable belief of SOA 2003, so the men were not guilty as

they genuinely believed in consent. Now S.1(2) says that whether a belief is reasonable is to

be determined having regard to all the circumstances, including any steps that A has taken

to ascertain whether B consent see Ciccarelli [2011]. In B (2013) D suffered from delusion

beliefs and believed he had sexual healing powers, he was still charged as a delusional belief

is still unreasonable under S1(2).

SENTENCE

Maximum life imprisonment

ASSAULT BY PENETRATION s.2

AR

1. penetration of the vagina or anus of another person with a part of their body or anything else

(finger, sex toys).

2. The penetration is sexual (not considered an assault in cases of surgery etc).

3. V does not consent to the penetration

MR intention to penetrate, and no reasonable belief in V’s consent.

SENTENCE

Maximum life imprisonment

SEXUAL ASSAULT s.3

AR

1. touching of another person s.79(9)

2. The touching is sexual. Meaning of sexual s.78

D’s conduct is sexual by nature, in Hill [2006] the defendant forcefully inserted his

fingers into his partner’s vagina during a violent argument, even though the conduct

was violent the nature of the act was sexual regardless.

D’s conduct may be sexual + it’s made sexual by circumstance or D’s purpose

In the case of practiti oners their purpose of touching and penetrating is different e.g.

doctors (medical reasons)

What if D removes V ‘s shoes for sexual gratification? The conduct is not sexual, but

it’s made sexual by the circumstances and D’s purpose, see George [1956] at the

time there was no offence as sexual assault, so the D was acquitted but today it could

be considered as an offence.

3. V does not consent to the touching

MR intention to touch and no reasonable belief in V’s consent

SENTENCE

Maximum 10 years imprisonment

CONSIDERING CONSENT OF THE ACTUS REUS

Consent is not a defence but rather a defence strategy, different from a defence like withdrawal in

complicity or self-defence where the act done is still a crime. In this circumstance the defence of

consent transform the offence into a non-offence. If the victim consented the AR is not complete and so

is the MR so no criminal liability.

Considering the AR – consent is an objective test considering the circumstances, and body language the

prosecution must follow. S.76 then S.75 and the S.74 to ascertain the V did not consented. Did the V

has the capacity to consent (must be careful if she is drunk but a drunken consent is still a consent).

1. S.76

D intentionally deceived V as to the nature or purpose of the act see Williams [1923] The

defendant was a singing coach. He told one of his pupils that he was performing an act to

open her air passages to improve her singing. In fact, he was having sexual intercourse

with her. It was held that her consent was vitiated by fraud as to the nature and quality

of the act.

See R v Jheeta [2007] the prosecution wanted to rely on this section but the court held that the

defendant was not deceived as to the nature of the act but rather the circumstances in which

the act came about so it was proper to rely on S.74 consider Assange v Swedish Prosecution

Authority [2011] the V did not wanted sex without condom, during the penetration the D

removed the condom the court held that the nature of the act (the penetration) was not

deceptive so the prosecution could not rely on S.76 but rather S.74. in contrast if V consent to

penile penetration and V uses prosthetic device then it comes under S.76 Also consider if D

deceives the V by not disclosing his gender.

Or D intentionally induces V to consent by impersonating a person known to V e.g.

boyfriend. See Elbekkay [1995] where the victim thought the D was his boyfriend by the

D did not said anything to induce such a thing so no s.76 but s.74. If neither if this apply

s.75

2. S.75 If D is aware of any evidential presumptions about consent then he is guilty unless he has

other evidence and then the prosecution may have to rebut this evidence beyond reasonable

doubt:

Causing C to fear immediate violence (like Costanza 1997) against themselves or another person

(goods or property are not considered).

C was unlawfully detained at the time or asleep or unconscious

Supplying a substance to overpower C (if it has no effect then it is rebuttable)

C has a physical disability that prevent her/ him to communicate non-consent. If neither if this

apply s.74

3. S.74 a person consents if they agree (active response) by choice and have the freedom (consider

abusive relationship) and capacity to make that choice consider Tyrell (1984) the V consented

but she was under the legal age (16) to have sex so the D was convicted.

Consent involves submission but not every submission involves consent Oluboja [1982].

Failure to disclose HIV status does not make it a sexual offence EB [2006] may be an offence

under S.20 OPA 1861.

MEANING OF PENETRATION S.79

S.79(2) Penetration is a continuous act, from entry to withdrawal, someone can consent at the

beginning and not after, if she wants the penetration to stop it must be within reasonable amount

of time (instantly) otherwise you commit an offence. Gender reassignment is considered s.79(3)

MEANING OF TOUCHING S.79(9)

Touching includes touching:

Any part of the body

With anything else

Through anything

Includes touching amounting to penetration. Touching through clothes is sufficient see R v H [2005] the

defendant grabbed her clothes.

THEFT

Is theft bad? Yes consider the harm to the victim: financial, sentimental loss. Illegitimate means of

acquisition. Harm to society (social order).

Free gains = taking things that are free e.g. from a bin. See Thomas [2010]. What is being protected? A

property

Theft Act 1968 A person is guilty of theft if he dishonestly appropriates property belonging to another

with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it…

AR:

Appropriates

There is appropriation if the defendant has assumed any of the rights of the owner, e.g. touch,

sell or destroy the property; if you take someone’s property and then sell it back to them it can

still be considered as theft as you assumed a right that only the owner could have assumed

If you buy a property and later realize it was stolen it cannot be theft.

theft occurs earlier, when the defendant picks the object in the store but if you want to better

prove the crime (dishonesty) you wait till D walks out from the shop so they know you

intentionally want to deprive the store.

Property

Real property: exceptions to land and improvement to lands which is difficult to steal or can be

steal by limited people e.g. trustee or tenants. Things on the land e.g. trees cannot be stolen but

things like gardening equipment yes. A tenant won’t commit an offence if he removes anything

that is part of the land except for “fixtures and structures” e.g. a wall or staircase but not a

plant.

Anything that is growing wild cannot be stolen except if you are selling it to make profit.

Confidential info cannot be steeled see Oxford v Moss [1979], people and body parts cannot be

steeled unless the latter has been improved see Kelly [1999] (skill added).

Personal property: movable properties and cash (physical notes and coins)

Things in action: stocks, shares and cheques

Belonging to another

somebody is in possess or control (not necessary to own), trust, rights, property received under

obligation e.g. giving £5 to pay a bill but using it to do something else see Wain [1995] where he

was meant to put the money in a trust found but transfer it into his personal account without

putting nothing in the trust.

When there is a case of multiple interest the court will consider the property to belong to the

person who was the greater interest.

You can be charged if you still your own property when someone has added value to it, see

Turner [1971], if no value added then no Meredith [1973]

Abandoned property can still be theft see Ricketts v Basildon Magistrate Court [2010] also if is

on somebody else property or the owner does not know about it, in this case the defendant

took clothes that were left outside the pavement of a charity shop.

MR:

Dishonestly question for the jury applying the objective test, see Ivey v Genting Casino [2017].

Was what the defendant did classified as dishonest applying the reasonable test?

Would the defendant realize that reasonable and honest people would classify his conduct

as dishonest?

not appropriation if the D believes s/he has right to it as a matter of law (not morality) or

believes in consent, believes the owner is undiscoverable (reasonable steps to ascertain

themselves) e.g. Copy of a newspaper in a tube

Intention of permanently deprive

borrowing temporary is not enough. It does not need to be shown that the defendant wanted

to acquire the property. If I appropriate a bag and throw it away is theft.

Intention to return the property may be difficult to prove the dishonestly of the defendant. It is

theft only if the value is gone see Lloyd [1985] requires all the goodness, virtue and practical

value to be taken from the goods, in this case the films were just borrowed piracy.

If you are in a store and move a can of coke to a shelf close to the door with intention to take it

when you get to the door this is theft.

If you appropriate a ticket and return it after the concert is still theft as it is useless after the

concert see Beecham [1851]

ROBBERY = THEFT + FORCE or THREATENED FORCE AGAINST A PERSON just a minimal kind of force

and the use of force must be on the victim body see Dawson [1976] the defendant nudged, and it was

considered as a force. Sentence imprisonment for life

CRIMINAL DAMAGE

The new law of criminal damage covers: Criminal Damage, Aggravated Criminal Damage, Arson and

Aggravated Arson.

This offence distinguishes itself from Theft by the use of force/violence on the property e.g. arson

removing the value of the property.

CRIMINAL DAMAGE ACT 1971 s.1

A person who without lawful excuse destroys or damages any property belonging to another intending

to destroy or damage any such property or being reckless as to whether any such property would be

destroyed or damaged shall be guilty of an offence.

CRIMINAL DAMAGE

AR

Destroys or damages Is a question for the jury to answer and the meaning is broad e.g.

temporarily affecting the land even if the property is still ok e.g. dumping rubbish into somebody

property; not intention to permanently deprive, which is theft. See Hardman v CC of Avon

[1986] even if there was no actual damage the council had to spend money and time to rectify

the damage. Graffiti on a wall can constitute damage see Roe v Kingerlee [1986]

No need for severity see Gayford v Chouler [2005] the grass was going to grow back but it was

still considered damage as they were told not to walk on it.

Damage even if there is no physical effect e.g. removing a programme from a hard disk.

MR

Any property s.10 similar to theft; tangible items (real property, personal property, not things in

action/intangible things or things that are not in property see Gayford v Chouler [2005])

Belonging to another s.10 in custody or control of another person, the person who has more

interest in the property is the owner. It cannot be the Defender

Intent or recklessness as to the damage direct and indirect intention considered and

Cunningham reckless since R v G and others [2003] (boys who didn’t realise the risk of their

action) subjective test where the D foresaw the risk of criminal damage by his act, and in the

circumstances known to him it was unreasonable to take the risk.

the man who tripped in the Cambridge museum could not be charged as he lacked intention or

recklessness as to the damage of the property BBC News Online 2006d.

The fact that you do not realize that what you have done is damage in the eyes of the law does

not constitute a valid defence because you still had the intention to damage the property see

Seray Wurie v DPP [2012].

Intent or recklessness as to the ownership direct and indirect intention as to belonging to

another (deliberate intention or hope of property belonging to another) and subjective

recklessness (foresee that it could be someone’s) or also if D has not though about it. See Smith

[1974] he fixes a stereo wiring panel damaging the landlord’s property with intention to damage

the property but no intention or recklessness to the belief of property belonging to another as

he thought it was his.

SENTENCE 10 yrs imprisonment

Problem question

David puts up a poster on university property is he liable for criminal damage?

Destroys or damage = no actual damage of the property. Unless it is significant

Property = says that it is a property in the problem question probably a wall

Belonging to another = says that is the university property

Intention/ recklessness as to damage = probably didn’t even recognised he was damaging

anything so not even recklessness

Intention/recklessness as to belonging = he knows that it is the property of the university

Conclusion = there will hardly be an offence here, as there is no actual damage and there in no

intention to damage the property.

AGGRAVATED DAMAGE

AR

Destroys or damages s. 1(2)

Any property

Belonging to another or himself considers also the D’s property see Merrick [1995]

Intention/ recklessness as to the damage/destruction

Intention or recklessness as to the endangering of life by conduct, is the damage to the

property that has to endanger the V’s life not e.g. the weapon used see Steer [1988] the bullets

were clearly meant to endanger life but the bullet hit the glass and the glass endangered life so

he was acquitted as he did not intend the glass to endanger life but rather the bullet itself;

MR

it does not need to be shown that the property that endangers the life of others is the one that

the D damaged.

No requirement of the act to actually happen just MR not AR see Webster [1995]. Subjective

recklessness.

This offence overlaps with the Offences Against the Person Act and if you intend a harm but does not

actually happen it could be an attempt.

Sentence = life imprisonment

ARSON

S. 1(3) JUST ADD FIRE

ARSON = CRIMINAL DAMAGE + FIRE

AGGRAVATED ARSON = AGGRAVATED CRIMINAL DAMAGE + FIRE

STATUTORY DEFENCES

Lawful excuse S.5 + duress

1. S. 5(2)a CONSENT by the owner or person who he believed he was in control of the property

consented or would have consented. See Blake v DPP [1993] God cannot give consent but in

contrast Denton [1981] the employer gave him consent.

2. S. 5(2)b immediate need to protect the property through his criminal act; objective question on

facts as D believed them to be see Hill and Hall [1989] the threat was not in the immediate

future. You are protected even if the threat was not immediate, but you believed it to be

immediate although the more outrageous the D alleged belief the less likely the court is to

believe they genuinely held that belief.

BURGLARY

Burglary is different from Robbery as in the latter one the D is trying to steal while adding force to the

crime; the former instead, is related to buildings and trespass.

The offence of burglary is annotated in the THEFT ACT 1968 s.9 & s.10 and it has been reformed from

the previous common law offence which was Burglary & House Breaking.

As the sexual assault offence burglary can cause negative impacts on victims for instance sleeping

difficulties, cost involved, sentimental losses, invasion of privacy and so on.

How to prevent? Neighbourhood watch, private policing, surveillance and so on.

FRAMEWORK FOR BURGLARY

Burglary at entry s.9(1)a

Building – pre-entry intent

Aggravated burglary s.10(2)

Burglary + weapon

Domestic Burglary s.9(3)

Burglary + dwelling

Burglary while inside s.9(1)b

Building – without pre-entry intent

These are not separate offences, you chose either burglary at entrance or while inside, then you add

the other two if they apply to the case

BURGLARY AT ENTRY s.9(1)(a)

AR

1. The D enters is a question for the jury to answer. The entry must be effective not

necessary substantial in the Brown [1985] case only his upper body was trespassing but

the court held it was effective. It is also irrelevant if D is not in the position to commit the

offence anymore, see Ryan [1996] his arms got stuck in the window.

It can also be burglary if you train a dog to enter to other people’s house and steal see

Wheelhouse [1994] also guilty if you use an object to enter into people’s house.

2. As a trespasser is a civil law question unauthorised & unjustified. See Collins [1973] the

D was a trespasser because the daughter of the owner had made a fundamental mistake

over his identity,

Excludes liability when the D had legal authorisation e.g. licence or search warranty but D

must stay within the authorisation e.g. if you invite a friend and then you ask them to

leave but they don’t leave then they are a trespasser. Also see Jones and Smith [1976],

the father has given his son the authorisation to live in the house but not to steal things,

so he went over his authorisation and could be convicted (exceeded the permission

given). Is not an offence if D had the owner’s consent. Burglary at entry needs trespass at

entry.

3. Any building or part of a building things that cannot be lifted easily see s.9(4) inhabited

vehicle or vessels. Not necessary that you are inside the building when the offence

happens. But a pure vehicle which is not inhabited is not included see Norfolk v Seeking

[1986] (large container that formed part of a lorry was not considered). You are also a

trespasser if you have the permission to enter into parts of the building e.g. a student

may have the authorisation to enter into communal area of the university but not staff

only areas.

MR

1. Intention or recklessness as to the trespass you need intention or recklessness that you

are not allowed to enter into the building or part of the building; so intent or reckless as

to exceeding the terms of authorisation. The D has to know that he is a trespasser or be

reckless (e.g. they entered into a building without permission of the owner); see Collins

[1973] the D was a trespasser because the daughter of the owner had made a

fundamental mistake over his identity, but he honestly believed he was invited in, so he

did not know he was a trespasser and could not be convicted (he lacked the MR of being

a trespasser).

2. Intent to commit: for s.9(a) intention to commit these offences must be present at the

time of entry. This is a MR requirement so there is no need for the actual offence to be

committed and if he entered the building with no intention to steal but after he steals is

not s.9(a) anymore.

THEFT AR appropriation, property, belonging to another, MR dishonesty, intention to

permanently deprive

GBH AR wounding or GBH, MR intention or recklessness as to wound

UNLAWFUL DAMAGE AR damage, property, belonging to another, MR intent or

recklessness as to damage, intent or recklessness as to the ownership

Patricia the Postwoman is using her well recognised uniform to go onto people’s land and wander

around looking for things to steal.

Issue:

She enters yes but what? Building part of a building?

As a trespasser yes her licence evaporates as she has the intention to steal not to give letters

Any building or part of a building we do not know that from the information given

Intention or reckless as to the trespass yes probably

Intention to commit theft yes as she wander around looking for things to steal.

BURGLARY WHILE INSIDE s.9(1)(b)

The D decides to commit the Theft, GBH while inside not when he still have to enter into the property;

so at the point of entry;

AR

4. The D enters is a question for the jury to answer. The entry must be effective not

necessary substantial in the Brown [1985] case only his upper body was trespassing but

the court held it was substantial. It is also irrelevant if D is not in the position to commit

the offence anymore, see Ryan [1996] his arms got stuck in the window.

It can also be burglary if you train a dog to enter to other people’s house and steal see

Wheelhouse [1994] also guilty if you use an object to enter into people’s house.

5. As a trespasser is a civil law question unauthorised & unjustified. See Collins [1973] the

D was a trespasser because the daughter of the owner had made a fundamental mistake

over his identity, but he honestly believed he was invited in, so he did not know he was a

trespasser and could not be convicted (he lacked the MR of being a trespasser).

Excludes liability when the D had legal authorisation e.g. licence or search warranty but D

must stay within the authorisation e.g. if you invite a friend and then you ask them to

leave but they don’t leave then they are a trespasser. Also see Jones and Smith [1976],

the father has given his son the authorisation to live in the house but not to steal things,

so he went over his authorisation and could be convicted (exceeded the permission

given). Is not an offence if D had the owner’s consent. Burglary at entry needs trespass at

entry.

6. Any building or part of a building things that cannot be lifted easily see s.9(4) inhabited

vehicle or vessels. Not necessary that you are inside the building when the offence

happens. But a pure vehicle which is not inhabited is not included see Norfolk v Seeking

[1986] (large container that formed part of a lorry was not considered). You are also a

trespasser if you have the permission to enter into parts of the building e.g. a student

may have the authorisation to enter into communal area of the university but not staff

only areas.

MR

3. Intention or recklessness as to the trespass you need intention or recklessness that you

are not allowed to enter into the building or part of the building; so intent or reckless as

to exceeding the terms of authorisation. The D has to know that he is a trespasser or be

reckless (e.g. they entered into a building without permission of the owner); see Collins

[1973] the D was a trespasser because the daughter of the owner had made a

fundamental mistake over his identity, but he honestly believed he was invited in, so he

did not know he was a trespasser and could not be convicted (he lacked the MR of being

a trespasser).

AFTER THE DEFENDANT IS INSIDE THE PROPERTY

4. Intent to commit: This is a MR requirement so there is no need for the actual offence to

be committed but in the case of s.9(b) the D must do something that is mere that

preparatory or commit the full offence.

THEFT or ATTEMPTED THEFT e.g. reaching or touching the object

GBH or ATTEMPTED GBH e.g. missing the person you want to stab

AGGRAVATED BURGLARY s.10 THEFT ACT

BURGLARY +:

FIRARM includes imitations, no need to be fire able

WEAPON anything that is made/adapted/intended for causing injuries e.g. if a throw a chair or a

boiled kettle or a screw driver. The D must be aware that he has the weapon with him at the

time of the burglary.

The weapon does not have to be used, the defendant only needs to carry it with him at the time

that he was committing the offence; but it must be shown that he intends to use it to injure

someone see Kelly [1993] So if a burglary is charged under s.9(1)(a) it must be shown that the

weapon was carried at the moment of entry into the building, on the other hand under s.9(1)(b)

it must be shown that the D had the weapon when he was committing the further offence or

Theft or GBH see Francis [1982].

SENTENCE

INDICTABLE OFFENCE dwelling + violence, also 3rd time domestic burglary, and if you commit

GBH. S.9(3) for dwelling up to 14 years, others up to 10 years. AGG BURG life imprisonment.

SUMMARY OFFENCES up to 26 weeks custody and or unlimited fine

What is a Dwelling?

May be a house, flat or a garage linked to the dwelling by a connected door see Rodmell [] it includes

sheds.

PRIVATE DEFENCE

DEFENCE FRAMEWORK:

AR + MR – DEFENCE = CRIMINAL LIABILITY

Defences prevent liability where the conduct is excusable or justifiable; they also explain why the

defendant acted in that particular way.

When is it justifiable (is OK) to harm or kill a person? Is a very high threshold

Threat to your life? Yes

Burglary? Sometimes. The defence must balance the offence e.g. if someone is trying to kill you,

you kill them but if they are just robbing is not a balance to kill them

Terrorists? Yes

This should be distinguished from excuses when you are excused from liability based on the facts

surrounding the case and the Defendant characteristics even if what you did was not ok e.g. insanity.

An example is the De Menezes killing, he was mistaken for a terrorist and was shot 7 times in the head

by the police force, the court held that it was excusable as the police was trying to protect the public

interest.

TYPES OF DEFENCES

Loss of control partial defence for murder (based on the defendant state of mind)

Insanity (based on the defendant state of mind)

Diminished responsibility partial defence for murder (based on the defendant state of mind)

Statutory defences e.g. Criminal Damage consent or Theft etc.

(private defence) Self Defence to any crime (based on the finding that D acted in a permissible

way)

Self-defence was a common law doctrine, but now it has been augmented by the Criminal Law

Act 1967 s.3 prevention of crime and the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 s.76 which

gives a definition or reasonable force.

Threat, to D, or another person or to a property by physical force also threat to

autonomy and freedom or protection e.g. if you are detained or locked in a room

The threat needs to be imminent (broad interpretation), pre-emptive response to threat

see Kelly [] the soldiers shot the driver of the car believing he was a terrorist. So a man

about to be attacked does not have to wait till he is attacked. Is not necessary to show

that the treat is imminent or immediate so if your kidnapper is asleep you can use force

against him even if he is asleep and not causing any treat.

unjustified, the threat has to be unjustified not necessarily a criminal threat, if it’s

criminal you rely on the Criminal Law act otherwise you rely on common law e.g. if a

child bites a carer he can’t be criminal liable because he lacks capacity but you can

prosecute under common law.

D does not have to provoke the threat e.g. insulting V so that V hits him and he can hit

him back see Robinson [1985] or Mason.

But if you provoke V and he responds disproportionately the tables can turn e.g. d insults

V and V pull a gun then D can defend himself against V see Keane [2010]

In Jones [2006] a crime committed in an attempt to stop the Iraq war was not regarded

as justifiable because the act of going to war in Iraq was not an offence under English

Law

reasonable to use force, what type of force? violence + smashing a window + breaking

down a door it excludes for example writing with a pen as the amount of force used is

very limited see Blake []

Was it necessary to use force in that particular circumstances? E.g. to prevent entry just

lock the door no need to shoot.

When there is violence there is a duty to retreat under common law but not under the

Criminal Law act e.g. if you are in a bar and there is violence. No duty to retreat if you are

in a public place and you are not initiating any violence even if you are in place where

you are hated. Under s.76(6a) there is no duty to retreat so still qualify for the defence

under criminal law.

Necessity has t be considered e.g. in common law allowed to damage or steal property to

save a person or a property or for the public interest. Where d has to take action for the

benefit of someone else because he is unable to consent; where the police direct to

break traffic regulations if necessary to protect life or property. Sometimes it is allowed

to kill see conjoined twins [2001] case where doctors separated the twins and one died

for the benefit of both of them but the act must be essential to avoid the evil, and no

more than a reasonable action should be taken and the evil inflicted must not be

disproportionate to the evil avoided.

reasonable amount of force used, s. 76(9) question for the jury

Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 s.76(6) not disproportionate

The force used as a defence must match the force used in relation to the treat so if V

insult the D he can’t shoot him or stab him to death. So the force used must

proportionate in the circumstance s. 76(6) not necessarily precisely proportionate as it

must be considered that D is acting in the heat of the moment see Keane [2010]

If you use a disproportionate force then you do not qualify for the defence, but it can still

impact the sentencing because you were being provoked except for murder as

mandatory life imprisonment see Yaman [2012]

the degree of force is an objective test. The facts to be taken into consideration are the

ones as D believed them to be and then the jury will evaluate based on those facts if the

force used was reasonable. So if D honestly believed that the man in the other room was

a big man holding a gun and he shoot him first and find out it was a nanny the jury must

take into consideration if it was reasonable to have used a gun to face the presumed

man with a gun in this case it is likely that the jury will find that it was reasonable to have

used that degree of force. But the s.76(6) says D must be honest as to the facts that he

believed them to be.

Was it reasonable to

have used that

degree of force ?

facts know to the D

s.76(6) was D honest

and instinctive?

in defence of himself another or property.

A. Common law

D believes she was facing a threat from the victim and the force used in the

circumstances as D believed them to be was reasonable. Doesn’t have to be accurate

B. Criminal Law Act 1967 s.3

“A person may use such force as is reasonable in the circumstances in the prevention of

crime, or in effecting or assisting in the lawful arrest of offenders or suspected offenders

or of persons unlawfully at large”.

Whilst in common law you can use force to prevent any threat, in the criminal act you

can use force only to prevent a criminal threat e.g. somebody jumping in front can be a

threat but also an assault.

On Defence of Property it needs to fit with s.3 of the Criminal Law Act, so there is a need of a crime that

D is trying to prevent see Ayliffe [] the protesters were protesting on the military base but the crime

was actually in Iraq, so they were not following s.3 of the Criminal Law Act

HOUSEHOLDER CASES

Householder cases are treated differently Crime and Courts Act 2013 amendment of the Criminal

Justice and Immigration Act 2008 s.76. what counts as a household s.76(8a.b.c.f) if V. was believed to

be a trespasser by the D

It is applicable to self-defence and defence to others not included for defence of property. In this case

the degree of force to be used is up to “grossly disproportionate” force s.76(5a) it is Ok in a

householder case to use a force that its disproportionate but if you are grossly disproportionate then

you do not qualify for the defence.

see Tony Martin [2002] case the threat was running away and he used a force that was grossly

disproportionate. It would have been different if he would have been used that same force if the

burglar was still inside the house or was fighting with him.

In normal cases the question to answer is: was the force reasonable?

In householder case the question to answer is: was the force grossly disproportionate?

INTOXICATION

For Basic Intent

Crimes

Dangerous drug

Non-dangerous drug

Liable unless would

not have foreseen

even if sober

Liable if reckless as to

becoming

dangerous/aggressive

Voluntary

Yes - liability possible

For Specific Intent

Crimes

Is there Mens Rea

even with presence of

intoxication?

No - acquittal.

But note possibility of

liability for lesser

(especially basic

intent) crimes

Intoxication

Yes - Liability possible

Involuntary

Is there Mens Rea

even with presence of

intoxication?

NO - Acquittal

Involuntary = broadly excusatory

We excuse the defendant because it was not his fault. Unaware of the spike not necessary of all

the alcohol only the huge spiking. If nobody spikes you and you drink beer but it is stronger than

beer it is your fault. After the intoxication the court will ask if you were able to form the guilty

mind see Kingston [] he was drugged but then committed child sexual offence. did he have the

MR?

What counts as intoxication? Alcohol and drugs see Lipman [], prescription drugs.

Problem question

Barnabus is on a sport social and his teammates add extra vodka to every drink that he has without his