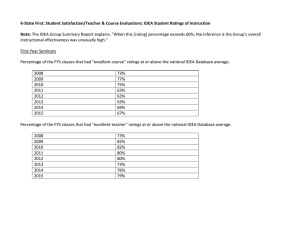

A Study of the Relationship of Socioeconomic Status & Student Per

advertisement