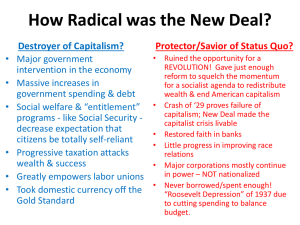

<$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 1 The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development Moisés Balestro (University of Brasilia) and Andreas Nölke (Goethe Universität in Frankfurt) Abstract The rise of large emerging markets such as China and India has made the debate about the role of the state in development very lively again. Several scholars argue that the role of the state in emerging market capitalist dynamics can be better grasped under the umbrella of state capitalism. This mirrors – and threatens to repeat – debates about the role of the state during the East Asian miracle in the 1980s and 1990s. Debates on an active role of the state in economic development need to avoid the danger of reinventing the wheel. More importantly, the dominance of the modern Anglo-American debate leads to a neglect of important older contributions from other national traditions. Our excavation of classical Japanese, German and Latin American contributions demonstrate the rich contribution of these alternative traditions. In contrast to the somewhat economistic, micro-economic and often supply-side focused contributions of the dominant Anglo-American debate, the forgotten traditions much more strongly highlight the importance of a common national vision for catch-up industrialization, a macro-economic and a demand-side perspective. Introduction The rise of large emerging markets, and particularly the case of China, has made the debate about the role of the state in development very lively again. A broad debate on emerging markets‘ state capitalism has been ongoing for a couple of years in Western media such as Time PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 2 Magazine (Schuman 2011), Businessweek (Kurlantzick 2012), the Economist (2012), Reuters (Bremmer 2012), or the Wall Street Journal (Sharma 2013). Usually, the term ―state capitalism‖ takes on a pejorative meaning in public debate, but this is often inappropriate (Rodrik 2013). The subsequent academic debate on state capitalism (Grugel and Riggirozzi 2012, Lin and Mulhaupt 2013, McNally 2013, Xing and Shaw 2013, Carney 2014, Schweinberger 2014, Nölke 2014, Hsueh 2011, 2015, Kalinowski 2015, Nölke et al. 2015, Kurlantzick 2016) came to a much more nuanced assessment. Our concern, however, is that the current wave of engagement with state capitalism tends to neglect the contributions made in previous scholarship and policy, thereby not only threatening to reinvent the wheel but also missing relevant insights. After all, this is already the third wave of engagement with state capitalism (ten Brink and Nölke 2013, Nölke 2014). The first wave of state capitalism happened during the mid- to late 19th century and had the trade protectionism as a critical issue. It included countries such as the US, Germany, parts of Scandinavia, and later Japan. Inspired by authors such as Hamilton (1791/2001) and List (1841/2014), the target was the development of the domestic industry, in order to avoid colonization by a superior economy (mainly the United Kingdom). Tariffs were a particularly important device for state capitalism during this period, supplemented by the creation of central banks and other new economic institutions. Later, state capitalism became less fashionable, especially during the 1920s, with its rather liberal outlook. The second wave of state capitalism refers to the highly important role of the state in the economies of the US, Europe, and the Soviet Union after the Great Depression. It also comprises the emergence of the East Asian developmental states after the end of the Second World War. This wave of state capitalism differed considerably from the first one, as it was much less based PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 3 on tariffs, but rather on the idea of a centrally planned modernization of the economy. The latter came in different guises, from the US New Deal, the Swedish model, Fascism, and Stalinism to the 1950s/1960s economic success stories of Japan and South Korea. The second wave of state capitalism stemmed from a comprehensive state intervention into the economy. In contrast to the first one, it was more developmental than protectionist. Central agencies such as the Japanese MITI set priorities for business and other economic actors. Domestic interventionism becomes coupled with multilateral trade with incremental trade liberalization as described by the concept of ―embedded liberalism‖ (Ruggie, 1982). After decades of dominance on industrial policy, the developmental state model (Johnson 1982, Wade 1990, Evans 1995; see also Chang 2002, 2010, Fine 2005, Edigheji 2010, Evans 2010, Sasada 2013) lost its predominance during the 1980s and 1990s and gave way to neoliberalism, as symbolized by the rise of the Reagan and Thatcher governments. The third wave of state capitalism in large emerging markets such as China, India, or Brazil again has a different focus, since it neither departs from prohibitive tariffs nor is it based on a centralized economic command. While it also includes protectionist measures as well as a certain degree of economic coordination, the strategic and selective use of both inward and outward foreign direct investment (FDI) for national economic development is the core pillar of this third wave. In current literature, state capitalism is nearly wholly associated with the rise of stateowned or at least state-supported companies from emerging markets (Baccini et al. 2017, Nem Singh and Chen 2017, Chaisse 2018, Cooke et al. 2018, Feng et al. 2018, Li et al. 2018, Yang and Lee 2018; Lim 2018, Arnold et al. 2019, Dolfsma and Grosman 2019, Hu et al. 2019). State capitalism thus is equivocated with the importance of state ownership, the support of national champions by public development banks and selective PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 4 industrial policies, often based on the influential work by Musacchio and Lazzarini (2014, Musacchio et al. 2015). Upon closer inspection, however, Hamilton (1791/2001), Japanese Meiji reformers, and the German Historical School (e.g., List 1841/2014) already have articulated many of the ideas forwarded during the most recent debates more than a century before. More importantly, the dominance of the modern Anglo-American (and, interestingly, often also Chinese) debate leads to a neglect of significant older contributions from other national traditions. Our excavation of classical Japanese, German, and Latin American publications demonstrate the rich contribution of the latter. In contrast to the somewhat economistic, micro-economic, and supply-side contributions of the current Anglo-American debate, the forgotten traditions much more strongly highlight the importance of a shared national vision for catch-up industrialization, a macroeconomic, structural and demand-side perspective. One could even claim that the topic of state capitalism recently has been appropriated by an implicitly liberal perspective. Correspondingly, we need to appreciate its less liberal origins, in order to make full value of the concept. In order to support this argument, the first section of our review essay highlights the common historical roots on catch-up industrialization from proposals put forward by Hamilton and the Meiji Restoration but mainly based on the more elaborate conceptualization of the German Historical School (List, Schmoller). The second section presents the theoretical contributions of the much-neglected ―organized capitalism‖ approach (Hilferding, Naphtali, Polanyi, Sombart) developed during the first half of the 20th century. Latin American authors have developed their approaches, first on ―structuralism‖ (Furtado), later on, ―new developmentalism,‖ with much attention given to macroeconomic issues (Bresser-Pereira, Fonseca) covered in section three. The PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 5 concluding section highlights the commonalities between the Japanese, German, and Latin American schools and their contribution to contemporary debates that still are strongly influenced by Anglo-American authors. 1 Hamilton, the Meiji reforms and the German Historical School: The importance of a sense of community Alexander Hamilton appears as one of the earliest thinkers and politicians that have propagated state-led catch-up industrialization. The importance of the state for economic development already had been highlighted by the earlier mercantilists. However, Hamilton was the first to highlight the specific role of public policies in order to temporarily shelter an emerging economy against the superior competition by the leading power on global markets, in this case, Britain. Concerning Britain, the US was considered a latecomer at that time. Hamilton presented four central policies to the American Congress, which later were incorporated by List and other reformers. These were 1) tariffs on imports; 2) direct subsidies, or "bounties," for domestic manufacturers; 3) a partially public-owned national bank and 4) significant public investments in infrastructure, or "internal improvements," like roads, canals, and ports (Parenti, 2014). In his famous "Report on Manufactures" from December 5, 1791, Hamilton (1791/2001) mentions the importance of the government for the late industrializing countries. In particular, he highlights the role of government to overcome the obstacles posed by the superiority of nations that developed earlier their manufacturing. According to Hamilton, the first US Secretary to the Treasury, to maintain upon equal terms the modern manufacturing from one country with the older from another in terms of quality and price, the interference and aid of government are indispensable. Thus, Hamilton opposed the universal laissez-faire ideas of Adam Smith, David PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 6 Ricardo, and others, at least for countries in a situation of the emerging United States vis-à-vis established Britain. As Cohen and DeLong (2016) remind us, it was the British approach that guided Germany's rapid industrialization, but the approach from Hamilton as presented from List. After that, this approach became spread in East Asia through Japan, then Korea, and now China. Hamilton's ideas were later carefully studied and followed by representatives of the Japanese Meiji Restauration (Austin, 2011). As in the case for Hamilton and the newly established United States of America, the main aim of the Meiji Restoration (1868-1885) was to establish an independent nation based on industrialization (and a strong army). As in the case of the late 18th century USA, industrialization was a response against the competition by superior economic powers with the forced opening up of Japan, e.g., by the interventions of the US Commodore Perry in 1853/4. As we shall see, however, the Japanese reformers added their particular twist to the ideas developed by Hamilton and others in the US. According to Crawford (2008), rather than the belief in the laissez-faire philosophy of the free enterprise, business activity became rationalized as service to the community and the state. The communitarian worldview is an enduring feature of the Japanese economic ideology. It also provided legitimacy to Japanese governments to put more faith in manipulation than in free competition. The most comprehensive elaboration of 19th-century ideas about state-led development, however, stems from Friedrich List and Gustav von Schmoller. List is considered the founder of the German Historical School (Historische Schule). While in the United States, he got in touch with the contributions from Alexander Hamilton as one of the founding fathers who first claimed the need to foster manufacturing. List (1841/2014) emphasized what he called productive power. For him, the powers to create wealth are much more important than wealth itself. The concept of PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 7 productive powers as the powers to create wealth includes industriousness, thrift, morality, and the intelligence of individuals, social, political, and civil institutions and laws, as well as the guarantee of continuance (Harada, 2000). About the role of the state, List (1841/2014) claims that the state should intervene when private business causes harm or when community interests become ruled out. At the same time, due to the role of actors and institutions, it does not result from the deliberate, intelligent design but is more experimentalist and, therefore, cannot be ascribed to the concept of a general model. As of List (1841/2014), the primary condition for the unity of the nation and long-standing national welfare occurs when private interests are subject to national interests. When establishing the common roots from the concepts of the developmental state, one must trace back to both macro and micro levels of analysis. At a macro-level, akin to List, Schmoller has put forward a general notion of institutional development. For Schmoller, values in the form of law, morality, and custom are embedded in institutions and play a leading role as the determinants of evolving institutions and consequent economic performance (Shionoya, 2005). Mostly, latecomers depend more on institutional endowments than laissez-faire to catch up with advanced countries (Shionoya, 2006). At a micro-level, institutional development is explained not so much by the free choice of autonomous individuals in markets, as by the sense of community and by coordinated actions based on shared values; both ideas and cultural values play a role in the economic rationality. Similar to Gao (1997), who highlights the role of ideology and shared beliefs in the economic catch-up process from Japan, Schmoller stresses this sense of community and coordinated action beyond market mechanisms. It is essential to remind that community here has a more general sense as shared interests, beliefs, and values than the standard concept of community from sociology. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 8 The original idea of social policy in Germany as a latecomer is related to German idealism. In the Kantian, as well as the Hegelian philosophical tradition, society, politics, and the state are examined from an organic, historical, and cultural understanding perspective, in opposition to utilitarianism (Schmoller, 1998; Blümle, 2006). Delving into Schmoller's arguments on social policy, Prisching (1997) points out two considerations that deserve attention when linking the historical school to contemporary discussions about the developmental state. First, Schmoller saw the economic value of the social policy. In this sense, improvements in morals and the expansion of education may promote the economic organization. Critical of methodological individualism, Schmoller (1895) claims that economic life is not a process mainly dependent on individual action, but instead on the collective organization with the rules for production and trade intercourse. For Schmoller, education and justice are collective factors of production. Second, industrialization yields social costs, and the social costs of industrial society need compensation. The compensation of these costs entails political regulation and constraint over the process of accumulation that goes beyond the sole profit-making rationale from capital. To conclude, the first generations of thinking on state capitalism were unified by the vision of national independence based on industrialization, implicitly directed against superior economic powers such as the United Kingdom (and later the United States). A core principle was that private (individual) profit interests have to overlap with common national interests. In order to organize this subjugation, reformers highlighted the importance of shared values and a sense of (national) community. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 9 2 German thinking on organized capitalism in the early 20th century: The importance of overriding collective goals A frequently overlooked stream of thinking about the role of the state in catch-up industrialization stems from German and Austrian scholars such as Hilferding, Naphtali, Polanyi, Sombart and Pollock in the early 20th century, around the notion of "organized capitalism" (Kocka 1974, Puhle 1984, Könke 1987, Höpner 2007, Callaghan and Höpner 2012, Nölke 2012, Nölke 2017, Nölke and May 2019). In contrast to the ideas developed by Hamilton, List, Schmoller, and the Meijis, the emphasis is less on the early stages of catch-up industrialization, but rather on its stabilization in times of economic crisis. Moreover, theories on organized capitalism do not focus exclusively on the state and public policies, but rather on the broader organization of business, particularly on cartels and the role of financial capital. With hindsight, it is possible to set out two different streams concerning the idea of 'organized capitalism' with further implications to the current heuristic use of this approach to understanding the capitalist dynamics of latecomers. One stream has to do with the state's role in the economy after the capitalist crises from the eighties in the nineteenth century. Fundamentally, organizing implies more collective action to develop productive forces, both at the organizational and technological levels, and more incentives and guided by the state. Growing influence from technicians and specialists in the public services introduced new behavioral standards and mentalities in the public services (Torstendahl 1985). One may claim that this type of organization is already in place in the state-led industrialization and further upgrading from latecomers, as discussed in section one above. Another stream relates to the social-democratic experience from the Weimar Republic in the twenties, but not entirely restricted to Germany, given that organized capitalism can also PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 10 contribute to explaining the New Deal experience in the USA. In contrast to the emphasis laid upon the state's role in economic growth, this second stream associates' organizing' to stabilizing and the establishment of social objectives for the large business, especially conglomerates and trusts, and the interlocking between the bank and industrial capital. Between 1873 and 1913, Germany went through rapid economic growth with four-fold GDP growth. It was not only growth but also a structural economic shift with a higher share from more technologically advanced branches (Kocka, 1975). Since the 1890s, there was steady cooperation between banks and industrial firms. The banks were concerned with the financing with long-term credit for the industrial firms. The representatives from banks were involved with the necessary management changes in the firms to improve the accounting methods and management as a whole, aiming at higher efficiency and profitability. The long-term support from banks protected firms from shortterm market fluctuations (Puhle 1984). In his famous essay "Probleme der Zeit," Hilferding (1924/1982) considers the organization of capitalism as an attempt to regulating and organizing productive social forces. In this sense, economic concentration, from the perspective of social-democracy, as opposed to the earlier principle of economic liberalism characterized by the anarchic competition principle. For such a reason, economic concentration as an ordering trend was positively rated (Könke, 1987). The instability of the capitalist production diminishes so that the crisis and its effects on workers become dwindled. Sound credit regulation by large banks taking part in the board of large industrial corporations, adequate monetary policy, and investment coordination by large firms in times of economic boom are some of the means to reduce the effects of market fluctuations. As Winkler (1974) reminds us, the concept of organized capitalism developed by Hilferding does not stem from state help in the course of the industrialization process, but from interventions to PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 11 stabilize an established capitalist system characterized by social and economic crises. The approach from organized capitalism assumes that the possibility of stabilizing capitalism is more realistic than its collapse (Winkler, 1974). Industrial relations also change due to this hierarchically organized capitalism. Unemployment is not so threatening on behalf of unemployment insurance, as once and there is more demand for higher labour skills with the further mechanization process and science applied to management (Hilferding, 1924/1982). The organization of great masses of workers under the control of few large companies opens the opportunity, according to Hilferding (1982), of democratizing the economy or, in other words, the option of broadening social control over the firms' objectives. Such objectives are under the scrutiny of collectively organized workers and the state. Furthermore, individual capitalist profit-seeking becomes subjected to the collective goals and a scientific organization of the overall economy (Könke, 1987). The primary underlying argument is that economic and political power concentration facilitates economic democratization, in contrast to liberal capitalism. One crucial aspect for the economic democracy (Wirtschaftsdemokratie) put forward by Hilferding (1924/1982), and Naphtali (1928) as a possibility brought about by organized capitalism is the ability to sway on the very content of the firms' policies. Such a thread of reasoning is very much in line with the German tradition of codetermination (Mitbestimmung). It means that the workers have a say in the way labour gets organized within the company. The concept of economic democracy is also akin to the Fabian model of industrial democracy (Könke, 1987). To wrap up, even as the situation now is not catch-up industrialization, but stabilization in times of economic crisis, Austrian and German thinking on organized capitalism during the early 20th century shares with the earlier generation of thinking on state capitalism the emphasis on the PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 12 importance of overriding collective goals. Hilferding, Naphtali, Polanyi, Sombart, and Pollock also favour social control over the objectives of individual firms. However, in contrast to the first wave of state capitalism, not only the state exercise this control, but it also financial capital or cartels. Economic concentration from this perspective can yield outcomes for social development, for example concerning economic democracy. 3 Structuralism, New Developmentalism and the Latin American debate: The importance of the demand side and of a macroeconomic perspective Theories about the advantages of state capitalism, however, are not a prerogative of the Northern hemisphere. On the contrary, the idea of an infant industry protection from List, as well as his other contributions, had support in Latin American intellectuals in the second half of the 19th century in Argentina, Chile, and Brazil (Helleiner, 2017). In this sense, the development of Latin American structuralism was not the inception of development economics in this region. Latin American Structuralism is an original theoretical contribution coming from Latin American economists that have shed light on the structural limits in economic development, with a particular focus on the role of the state. There are three building blocks for this approach (Cimoli and Porcile, 2016). One is the slow and irregular diffusion of technology from the centre to the periphery. Technology diffusion is particularly relevant when considering the role of the state in promoting initiatives to overcome technological backwardness. Science and technology interweave with the accumulation process. Only by incorporating science and technology in the accumulation of capital, it is possible to speed up the catching up process (Furtado, 2013). More recently, the structuralist approach (CEPAL, 2008) encompassed contributions from institutional literature coming from innovation systems and authors of the Schumpeterian stream. As put by Cimoli and Porcile (2016), the accumulation of technological and PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 13 organizational capabilities does not take place in a vacuum but within the limits and stimuli provided by institutions. A second block refers to specialization patterns, specialization in the export of agricultural products constrained Latin American countries to a static comparative advantage. Furtado (2013) was particularly critical of the Ricardian law of comparative advantages, which served as the primary rationale to justify specialization. For him, Ricardian law was unable to cope with the extreme inequality in the diffusion of technical progress in the production processes. Another weakness of comparative advantage was the fact that surpluses stemming from the export of agricultural products financed the diffusion of new consumption patterns rather than the formation of gross capital to invest in catching up process. The third block has to do with the persistent informal labour market in Latin America as well as the enormous unequal income distribution. Differently, from the East Asian developmental experiences, Latin American countries never managed to create an inclusive labour market for their abundant labour force. A large share of total employment is in low-productivity activities or self-employed subsistence sectors. A smaller share of skilled workers in firms hampers income distribution as low-skilled workers usually earn subsistence wages. The highly unequal income distribution also has severe negative repercussions over domestic demand, given the much lower propensity to consume of the affluent strata of society. The importance of the demand side with macroeconomic issues laid the foundation to cope with the developmental challenges concerning structural heterogeneity, abundant labour force, and lower levels of productivity (Furtado 1970; Prebisch, 1986, and Cimoli et al., 2005) Following Latin American structuralism, there is a new school of developmentalism with a greater emphasis on macroeconomics. The context of the development of the new school is the different global economic situation that has developed since the 1980s. The process of financialization has increased the PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 14 volatility of global financial flows, and a catch-up industrialization strategy has to put up with these speculative financial flows. The concept of "new developmentalism" was firstly coined by Luiz Bresser-Pereira, an important Brazilian scholar who was minister of planning and treasury in the eighties and the nineties. For new developmentalism, the key institution is a national development strategy. As of Bresser-Pereira (2010), "such a national development or competition strategy materializes into laws, policies, common understandings, and shared beliefs that orient innovation and stimulate investment; it is not formal or written, but it can easily be intuited by the observer" (p. 59). Similarly to the developmental state, new developmentalism is also normative in the sense of presenting the various elements for a catch-up strategy. Also, it draws on classical political economy authors such as Smith, Marx, and List, and partially on Polanyi (1944/2001). Following a classical political economy approach, new developmentalism stresses that "institutions are fundamental, and reforming them is a constant task insofar as, in the complex and dynamic societies in which we live, economic activities must be constantly reregulated" (Bresser-Pereira, 2010; p. 102). Far from being economicist, it takes into account not only the development of technological capabilities and production factors endowment in general but also ideational and political aspects. The nation is considered a collective actor and the state its primary nucleus of collective action. Moreover, new developmentalism requires an informal cross-class political coalition where cooperation supersedes domestic conflicts for the benefit of a national developmental strategy. The dynamics of social struggles is the outcome from cross-class coalitions, from political pacts and agreements carried out by these coalitions. The cross-class coalition from new developmentalism includes industrialists, bureaucrats, progressive intellectuals, and workers that stand for a coordinating role of the state in the economic system together with market governance (Bresser-Pereira, 2014b). There are two crucial elements for PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 15 this cross-class coalition. One is the role of the state to lead, through incentives and sanctions, the longterm industrialization strategy, and another is not to rely upon the agrarian elite's capacity to play an active role in the development strategy. The persistent substantial political power of the agrarian elites was undoubtedly a significant shortcoming in Latin American industrialization. The national development strategy, as a key and encompassing institution, "guides the main political and economic actors in their decision-making processes – politicians on how to define new public policies or reform existing ones, businesspeople on when and where to invest" (pp. 59-60). One aspect that highlighted by Bresser-Pereira (2010) is that new developmentalism must emerge from an internal consensus in order to become a real national development strategy. In contrast to the discussions covered in the previous sections, new developmentalism has a sharper focus on macroeconomic issues such as exchange rates and capital controls. This focus mirrors the global economic conditions since the 1980s, with strongly increased financial flows, but also the strong potential of an over-valued currency based on strong agricultural exports. As exchange rate appreciation through foreign savings is a significant cause of the Dutch disease, capital inflow controls are necessary for the sense that they avoid deindustrialization related to an overvalued currency. Also, capital inflows related to financial speculation and rentism become more constrained by this specific state action. An industrializing ideology is also a fundamental issue in the new developmentalism agenda in Latin America. The new, as well as the old developmentalism, are an ideology in the sense that a national development strategy requires an ideology and the very idea that economic development is a government enterprise and economic development itself is the ultimate goal from state action (Bresser-Pereira, 2007; Fonseca, 2012). By explicitly incorporating a social dimension in the new developmentalism, BresserPereira (2014) argues that: PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 16 "In the framework of a new developmentalism, each country now has the possibility of adopting effectively national development strategies – strategies that widen the role of the state in regulating markets, that create profit opportunities stimulating private investment and innovation, and that increase the country's international competitiveness while protecting labor, the poor and the environment" (Bresser-Pereira, 2014, p. 128) Beyond a normative approach for developmentalism and stemming from a historical analysis from 29 different governments in various Latin American countries, Fonseca (2014) was able to find three commonalities within those governments that could be labelled developmentalist. The first commonality is that developmentalist governments have a national project to overcome backwardness and present themselves as key actors in the building of a desirable future for the country. A shared common project is essential to build a developmental cross-class coalition (Bresser-Pereira, 2019). Bresser-Pereira stresses the role of ideas organized around an encompassing narrative. The second commonality is that these governments make clear that economic growth is set as a priority so that all policy measures are subject to this priority. Finally, the third commonality is that industrial upgrading is set as a priority to achieve economic growth so that measures in economic policies and institutional development lead to this direction. In sum, the third forgotten tradition of state capitalism departed from the previous two ones by highlighting the importance of the demand side of macroeconomic perspectives more general and cross-class coalitions. It not only demonstrated that the integration into global capitalism based on Ricardian economic advantages leads to economic stagnation (as today still can be seen in Russia and the Gulf economies) but also incorporated a new global economic situation and the related need to protect against speculative financial flows. Somewhat similar to the previous two PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 17 traditions, it underlines the importance of a unified national effort, now, however, based on cross-class coalitions (and against the agrarian elites). 4 Conclusion and implications for contemporary developmental state discussions Tracing the intellectual roots of the state-driven development thinking allowed us to rediscover classical thoughts about the institutional organizing of capitalism as the core pillar for economic and social catching-up. Common elements shared by these traditions include the need for catchup development against superior external economic forces in order to prevent economic or political colonization, the focus on the nation-state as a collective actor, a strong preference for industrialization (not only on agriculture and the exploitation of resources) and a central role for the state (tariffs, planning, macroeconomic stabilization) as support for the private sector. This survey highlights that none of the various schools of non-liberal development thinking can monopolize the various valuable insights for economic and social catch-up. However, the most valuable intellectual achievements of earlier lines of thinking are scantily present in more recent debates on state capitalism. Adding ideas, and providing more salience to political and social dimensions beams overseen nuances from catching-up strategies. From our perspective, mobilizing the intellectual tradition of non-liberal development thinking more diligently allows us further knowledge of the interplay between the economy and society. Current references to state capitalism as a development strategy for large emerging markets such as China contain a brief reference to Hamilton, Friedrich List, or the East Asian developmental state, if at all. A more detailed study of, e.g., the German Historical School or theories of organized capitalism, usually is absent, even if Breslin (2011) and Nölke (2012, 2017, Nölke and May 2019) recently re-engaged with some of these old writings. Still, even these recent writings PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 18 tend to neglect some of the lessons learned by earlier lines of scholarship, such as the role of mobilizing ideas and of an ideology of industrialization more specifically. A shared vision was a systematic component from the earliest latecomers onwards. The promise of industrialization links personal economic fates to pride regarding the fast development of the country, often mediated by national brands, foreign policy, mega-events (such as Olympic Games), or grandiose construction projects. Another essential advice for current discussions about a return of state would be to avoid a too technocratic view of these developmental strategies. By grasping the Wahlverwandschaft between the German Historical School, organized capitalism, and later Latin American schools of statist thinking, we can bring the political economy back into the economic development in latecomers-debate. Especially the constraining role of the state over firms' objectives, as propagated by thinkers of organized capitalism, gives us a crucial instruction for the general set-up of these strategies. An overarching national development strategy is a sine qua non condition for developmental state capitalism. We can draw more lessons from these frequently forgotten classical theoretical approaches for policymaking regarding catch-up processes in emerging market economies. The complex political nature of the state cannot be reduced to the support of the expansion of multinational corporations, as implicitly argued in the approaches that currently dominate the debate on state capitalism. A successful state-capitalist role implies the mobilization of cross-class coalitions, the mediation of conflicts, as well as a wide array of ideas encompassing an agenda beyond pure economic efficiency. Finally, the development of successful state-capitalist strategies today also has to take potentially adverse global economic conditions into account. In particular, the process of financialization PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 19 and the related volatility of financial flows, as well as currency relations, can constitute a significant hindrance to the successful organization of contemporary state-capitalist strategies. State capitalist projects, therefore, have to keep the domestic financial sector under strict control and, in particular, have to avoid a long-term currency overvaluation due to the deindustrializing effects of the latter. Most of these insights are absent in the contemporary debate that equates state capitalism with state-owned or state-backed companies, mostly from China. The earlier debate on the developmental state, however, still remembered most of these debates. A famous lineage between the German Historical School and more recent thinking about developmental state were the references to Friedrich List's concept of "kicking away the ladder" by early industrializers, as popularized by writers such as Ha-Joon Chang (2002) and Robert Wade (2003). In his seminal work on the developmental state, Johnson (1982) already places the Japanese experience in the ideational tradition from the German Historical School. He states that "the most striking structural characteristic of the capitalist developmental state is an implicit political division of labor between the tasks of ruling and the tasks of reigning—the politicians reign and the bureaucrats rule" (Johnson, 1982; p. 154). Unfortunately, the role of politicians and their leadership and inspiration has been underrated in the later literature on state capitalism. For Robert Wade (1990), the design and legitimation of a developmental strategy as well as of a national project is the first and most crucial element of a developmental state. In a more comprehensive review concerning the evolution of the developmental state in Japan, Sasada (2013) highlights the importance of ideational guidance. The ideational theory claims that once actors adopt a given set of ideas as their ideational guidance, they become committed to certain types of policies that comply with that guidance and reject policies that contradict it. In a similar PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 20 vein, Gao (1997) works out the idea of policy paradigms and hinges it on ideology when analyzing the role of economic ideology in Japanese industrial policy. However, the original developmental state literature did not reflect all insights developed by the traditions excavated by this contribution. Later contributions to the developmental state debate, however, very often did. The major disadvantage of the East Asian developmental state (debate) was its rather technocratic and often state-centric approach. This approach neglects the importance of the mobilization of broad social coalitions for developmental strategies in democratic states. In East Asia, the institutions of the developmental state, as well as the national development strategy itself, were the outcome of a compromise and resulted from the formation of a stable socio-political bloc (Amable, 2003). Discussions about the need to mobilize crossclass coalitions for a "democratic developmental state" have become particularly prominent in post-Apartheid South Africa (Edigheji 2010). Two traits have been highlighted in particular (Chang, 2010): First, developmental states must derive legitimacy from successful economic development. Second, developmental state action implies favouring specific sectors over others. At a policy level, this translates into selective industrial policies. In other words, state intervention entails a political preference for a particular cross-class coalition (usually industrial sectors, urban middle classes, and, sometimes, parts of working classes), leading to distributive conflicts. Given looming bottom-up pressures from society, also in the context of democratic transitions, this calls for a broadening of the sustaining cross-class coalition beyond industrial elites and the state, in particular by incorporating deliberative institutions as critical contributors to development (Evans, 2010). Fine (2005), finally, brings forth a political economy approach towards the late developmental state debate. In particular, it contains analytical variables to grasp PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 21 the interaction of national systems of accumulation with global, pervasive factors such as financialization and global value chains. The current company-centered debate on state capitalism has forgotten nearly all of these insights. Still, there is hope. Recently, some scattered empirical contributions have featured a number of the themes highlighted in our intellectual archaeology. Beeson (2017) puts the high degree of state control, the ability to reconcile competing interests, an extremely prudential engagement with global financial markets and an undervalued exchange rate as core implications of China's rise for the developmental state paradigm, reflecting the importance of the latter in Steinberg's broad survey of recent developmental state strategies (2016). Similarly, Yeung's (2017a,b) surveys of the more recent fate of the East Asian developmental state not only highlight the challenge of global financial integration (and, increasingly, crossborder production networks) but also of the need to develop much broader societal coalitions than the traditional focus on state support for business only. Finally, Wylde's (2018) study on Argentine development under the Kirchner's strongly underlines the need for "the creation and maintenance of a hegemonic ideology consistent with rapid, catch-up development" (p. 13). We hope that our review essay assists in putting the findings of these and other ongoing studies into a more comprehensive framework and – better still – seeking renewed inspirations with the classical authors, particularly those outside of the dominant Anglo-American debate. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 22 References Amable, Bruno (2003) The diversity of modern capitalism, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Arnold, Jakob, Anders Ryom Villadsen, Xin Chen and Chaohong Na (2019) Multi-Level state Capitalism: Chines State-Owned Business Groups, in: Management and Organization Review Vol. 15 No. 1, pp. 55-79. Austin, Ian (2011) Alexander Hamilton and Asian Capitalism, Perth, Edith Cowley University. Baccini, Leonardo, Giammario Impullitti and Edmund J. Malesky (2017), Globalization and State Capitalism: Assessing Vietnam‘s Accession to the WTO, CESifo Working Paper No. 6618, München, CESifo. Beeson, Mark (2017) What Does China‘s Rise Mean for the Developmental State Paradigm? In: Toby Carrol and Darryl S. L. Jarvis (ed.) Asia after the Developmental State: Disembedding Autonomy, pp. 174-198. Blümle, Gerold and Goldschmidt (2006) Gustav Schmoller, his heirs and the foundation of today's social policy in Schmollers Jahrbuch 126, pp. 177 - 195. Bremmer, Ian (2012) Are State-led Economies Better? Reuters Magazine July 3. Breslin, Shaun (2011) The ‗China model‘ and the global crisis: from Friedrich List to a Chinese mode of governance? In: International Affairs 87:6, 1323-1343. Bresser-Pereira, Luiz C. (2007) Macroeconomia da Estagnação: crítica da ortodoxiaconvencional no Brasil pós-1994, São Paulo, Editora 34. Bresser-Pereira, Luiz C. (2010) Globalization and competition: Why some emergent countries succeed while others fall behind, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 23 Bresser-Pereira, Luiz C. (2014) From old to new developmentalism in Latin America in Ocampo, José A. and Ros, Jaime (edit.) The Oxford Handbook of Latin American Economics, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Bresser-Pereira, Luiz C. (2014b) A construção política do Brasil: sociedade, economia e Estado desde a independência, São Paulo, Editora 34. Bresser-Pereira, Luiz C. (2019) Em busca do desenvolvimento perdido: um projeto novodesenvolvimentista para o Brasil, São Paulo, FGV Editora. Callaghan, Helen and Höpner, Martin (2012) Changing Ideas: Organized Capitalism and the German Left, in: West European Politics, Vol. 35, Issue 3. Carney, Richard W. (2014) The stabilizing state: State capitalism as a response to financial globalization in one-party regimes, Review of International Political Economy, advance online publication 23 September. CEPAL (2008), La transformación productive 20 años después: viejos problemas, nuevas oportunidades, Santiago de Chile, Naciones Unidades – CEPAL. Chaisse, Julien (2018) State capitalism on the Ascent: Stress, Shock, and Adaptation of the International Law on Foreign Investment, Minnesota Journal of International Law Vol. 27. Chang, Ha Joon (2002) Kicking away the ladder: Development strategy in historical perspective, London, Anthem Press. Chang, Ha Joon (2010) How to do a developmental state: political, organisational and human resource requirements for the developmental state, in Edigheji, Omano (edit.) Constructing a developmental state in South Africa, Cape Town, HSCR. Cimoli, Mario and Porcile, Gabriel (2016) Latin American structuralism: the co- evolution of technology, structural change and economic growth in Reinert, E., Ghosh, J., & Kattel, R. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 24 (2016). Handbook of Alternative Theories of Economic Development, Cheltenham, Edward Elgar. Cohen, Stephen and DeLong, Bradford (2016) Concrete Economics: The Hamilton Approach to Economic Growth and Policy, Boston, Harvard University Press. Cooke, Fang Lee, Wang, Dan and Jue Wang (2018) State capitalism in construction: Staffing practices and labour relations of Chinese construction firms in Africa, in: Journal of Industrial Relations Vol. 60, No. 1, pp. 77-100. Dolfsma, Wilfred and Grosman, Anna (2019) State Capitalism Revisited: a Review of Emergent Forms and Developments, in: Journal of Economic Issues Vol. 53, No. 2, pp. 579-586. Economist (2012) The Rise of State Capitalism: The Emerging World‗s New Model (Special Report), January 21st-27th. Edigheji, Omano (edit.) (2010) Constructing a democratic developmental state in South Africa, Cape Town, HSCR. Evans, Peter B. (1995) Embedded autonomy: states and industrial transformation, New Jersey, Princeton University Press. Evans, Peter B. (2010) Constructing the 21st century developmental state: potentialities and pitfalls in Edigheji, Omano (edit.) Constructing a democratic developmental state in South Africa, Cape Town, HSCR. Feng, Xunan, Anders C. Johansson and Ying Wang (2018) Strengthened State Capitalism: Nationalized Firms in China. Stockholm School of Economics Asia Working Paper No. 51. Stockholm, Stockholm School of Economics. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 25 Fine, Ben (2005) Beyond the developmental state: towards a political economy of development in Lapavitsas, Costa and Noguchi, Makoto (edit.) Beyond Market-driven Development: drawing on the experience of Asia and Latin America, London, Routledge. Fonseca, Pedro C. D. (2012) Do progressoaodesenvolvimento: Vargas na Primeira República in Bastos, Pedro P. Z. and Fonseca, Pedro P. D. A era Vargas: desenvolvimentismo, economia e sociedade, São Paulo, EditoraUnesp. Fonseca, Pedro D. (2014) Desenvolvimentismo: a construção do conceito in Calixtre, André Bojikian; Biancarelli, André Martins and Cintra, Marcos Presente e futuro do desenvolvimento brasileiro, Brasília, IPEA. Furtado, Celso (2013) Essencial Celso Furtado, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras. Gao, Bai (1997) Economic Ideology and Japanese Industrial Policy, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. Grugel, Jean and Pia Riggirozzi (2012) Post-neoliberalism in Latin America: Rebuilding and reclaiming the state after crisis, in: Development and Change Vol. 43, No. 1, 1-21 Hamilton, Alexander (1791/2001) Report on Manufactures December 5, 1791. Available at http://www.constitution.org/ah/rpt_manufactures.pdf. Access on July 31, 2019. Harada, Tetsushi (2000) Two developments of the concept of anschaulicheTheorie (concrete theory) in Germany and Japan in Koslowski, Peter (edit.) Methodology of the Social Sciences, Ethics and Economics in the Newer Historical School: from Max Weber and Rickert to Sombart and Rothacker, Heidelberg, Springer. Hilferding, Rudolf (1924/1982) Probleme der Zeit in Stephan, Cora (ed.) Zwischen den Stühlen oder über die Unvereinbarkeit von Theorie und Praxis - Schriften Rudolf Hilferdings 1904 bis 1940, Berlin, Verlag JHW Dietz. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 26 Höpner, Martin (2007) Coordination and Organization: the Two Dimensions of Nonliberal Capitalism, MPIfG Discussion Paper 07/12, Max-Planck-InstitutfürGesellschaftsforschung, Köln. Hsueh, Roselyn (2011) China‘s Regulatory State: A New Strategy for Globalization, Ithaca, Cornell University Press. Hsueh, Roselyn (2015) State Capitalism, Chinese Style: Strategic Value of Sectors, Sectoral Characteristics, and Globalization, Governance early view, 12 March. Hu, Helen Wei, Lin cui and Preet S. Aulakh (2019) State capitalism and performance persistence of business group-affiliated firms: A comparative study of China and India, in: Journal of International Business Studies Vo. 50, No. , pp. 193-222. Johnson, Chalmers A. (1982) MITI and the Japanese Miracle: The Growth of Industrial Policy, 1925-1975, Stanford, Stanford University Press. Kalinowski, Thomas (2015) Crisis management and the diversity of capitalism: fiscal stimulus packages and the East Asian (neo-) developmental state, in: Economy and Society, online publication 24 April. Kocka, Jürgen (1974) Organisierter Kapitalismus oder Staatsmonopolistischer Kapitalismus? Begriffliche Vorbemerkungen in Winkler, Heinrich August (ed.) Organisierter Kapitalismus Voraussetzungen und Anfänge, Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Kocka, Jürgen (1975) Unternehmer in der deutschen Industrialisierung, Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. Könke, Günter (1987) Organisierter Kapitalismus, Sozialdemokratie und Staat, Stuttgart, Franz Steiner Verlag. Kurlantzick, Joshua (2013) The Rise of Innovative State Capitalism, in: Businessweek, June 28. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 27 Kurlantzick, Joshua (2016) State Capitalism: How the Return of Statism is Transforming the World, Oxford, Oxford University Press. Li, Larry, Adela McMurray and Jinjun Xue (2018), in: Journal of Policy Modeling, Vo. 40, No. 4, pp. 747-766. Lim, Kean Fan (2018) Strategic coupling, state capitalism, and the shifting dynamics of global production networks, in: Geography Compass Vol 12, No. 11 Lin, Li-Wen and Curtis J. Milhaupt (2013) We are the (national) champions: Understanding the mechanisms of state capitalism in China, in Stanford Law Review Vol. 65, pp. 697-760. List, Friedrich (1841/2014) Das nationale System der politischen Ökonomie, Berlin, Heptagon Verlag. McNally, Christopher (2013) The challenge of refurbished state capitalism: Implications for the global political order, in: dms – der modern staat, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 33-48. Musaccio, Aldo and Sergio G. Lazzarini (2014) Reinventing State Capitalism: Leviathan in Business, Brazil and Beyond, Cambridge, Harvard University Press. Musacchio, Aldo, Sergio G. Lazzarini and Ruth v. Aguilera (2015) New Varieties of State Capitalism: Strategic and Governance Implications, in: The Academy of Management Perspectives Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 115-131. Naphtali, Fritz (1928) Wirtschaftsdemokratie: Ihr Wesen, Weg und Ziel, Berlin, Verlagsgesellschaft des Allgemeinen Deutschen Gewerkschaftsbundes. Nem Singh, Jewellord and Geoffrey C. Chen (2017) State-owned enterprises and the political economy of state-state relations in the developing world, in: Third World Quaterly PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 28 Nölke, Andreas (2012) The Rise of the ‚B(R)IC Variety of Capitalism‘ – Towards a New Phase of Organized Capitalism?‖, in Overbeek, Henk und Bastiaan van Apeldoorn (eds.), Neoliberalism in Crisis, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 117-137. Nölke, Andreas (2014) Introduction: Towards State Capitalism 3.0, in: Nölke, Andreas (ed.), Multinational corporations from Emerging Markets: State Capitalism 3.0, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan. Nölke, Andreas (2017) Brexit: Toward a New Global Phase of Organized Capitalism? In: Competition & Change Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 230-241. Nölke, Andreas and May, Christian (2019): Liberal versus Organised Capitalism: A Historical Perspective, in: Tamás Gerőcs/Miklós Szanyi (ed.) Market Liberalism and Economic Patriotism in the Capitalist World-System. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 21-42. Nölke, Andreas, ten Brink, Tobias, Claar, Simone, and Christian May (2015) Domestic structures, foreign economic policies and global economic order: Implications from the rise of large emerging economies, in: European Journal of International Relations Vol. 21, No.3, pp. 538–67. Parenti, Christian (2014) Reading Hamilton from the Left, in: Jacobin online. Available at: https://www.jacobinmag.com/2014/08/reading-hamilton-from-the-left/ Access on April 8. Polanyi, Karl (1944/2001) The Great Transformation: the political and economic origins of our time, Boston, Beacon Press. Prisching, Manfred (1997) Schmoller's Theory of Social Policy in Backhaus, Jürgen (edit.) Essays on social security and taxation: Gustav Schmoller and Adolph Wagner resonsidered, Marburg, Metropolis Verlag. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 29 Puhle, Hans-Jürgen (1984) Historische Konzepte des entwickelten Industriekapitalismus. "Organisierter Kapitalismus" und "Korporatismus" in Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Vol. 10., No. 2.pp. 165-184. Rodrik, Dani (2013) The New Mercantilist Challenge, January 9, Project Syndicate. Sasada, Hirinori (2013) The evolution of the Japanese Developmental State: institutions locked in by ideas, London, Routledge. Ruggie, John G. (1982) International Regimes, Transactions, and Change: Embedded Liberalism in the PostwarEconomic Order in International Organization, Vol. 36, No. 2, International Regimes. Schmoller, G. (1895). The Mercantile System and Its Historical Significance, London, Macmillan and Co. Schmoller, Gustav (1998) Historisch-ethische Nationalökonomie als Kulturwissenschaft: ausgewählte methodologischen Schriften, Hrsg. von Heino Heinrich Nau, Marburg, Metropolis Verlag. Schuman, Michael (2011) State Capitalism vs. the Free Market: Which Performs Better? in: Time Magazine, September 30. Sharma, Ruchir (2013) How Emerging Markets Lost Their Mojo, Wall Street Journal, June 26, p. A 17. Shionoya, Yuichi (2005) The Soul of the German Historical School, Wiesbaden, Springer. Shionoya, Yuichi (2006) Schmoller and Modern Economic Sociology in SchmollersJahrbuch 126, pp. 177 - 195. Schweinberger, Albert (2014) State Capitalism, Entrepreneurship and Networks: China‘s Rise to a Superpower, Journal of Economic Issues,Vol. 48, No. 1, pp. 169-180. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 30 Steinberg, David A. (2016) Developmental states and undervalued exchange rates in the developing world, in: Review of International Political Economy Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 418-449. ten Brink, Tobias and Nölke, Andreas (2013) Staatskapitalismus 3.0, in: dms – der modern staat, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 21-32. The Economist (2012) Who‘s Afraid of Huawei?, August 4th. Torstendahl, Rolf and Frevert, Ute (1985) Das Konzept des Organisierten Kapitalismus und seine Anwendung auf Schweden in Geschichte und Gesellschaft, Vol. 11. No. 1, pp. 90-98. Wade, Robert (1990) Governing the market: economic theory and the role of the government in East Asian industrialization. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Winkler, Heinrich A. (1974) Vorläufige Schlußbemerkungen in Winkler, Heinrich August (ed.) Organisierter Kapitalismus: Voraussetzungen und Anfänge, Göttingen, Vandenhoeck& Ruprecht. Wylde, Christopher (2018) Twenty-first century developmental states? Argentina under the Kirchers, in: Third World Quaterly Vol. 39 No. 6, pp. 1115-1132. Xing, Li and Tim Shaw (2013) The Political Economy of Chinese State Capitalism, in: Journal of China and International Relations Vol 1, No. 1, 88-113. Yang, Yueh-Ping and Pin-Hsien Lee (2018) State capitalism, state-owned banks, and WTO‘s subsidy regime: proposing an institution theory, in: Stanford Journal of International Law Vol. 54. Yeung, Henry Wai-chung (2017) State-led development reconsidered: the political economy of state transformation in East Asia since the 1990s, in: Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 83-98. PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS <$surname> / The Importance of a Common Vision: Forgotten Traditions of Thinking about the Importance of State Capitalism for Socio-Economic Development / 31 Yeung, Wai.chung Yeung (2017) Rethinking the East Asian developmental state in ist historical context: finance, geopolitics and bureaucracy, in: Area Development and Policy Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 1-23. ### PROOF COPY – DISTRIBUTED FOR SUGGESTIONS