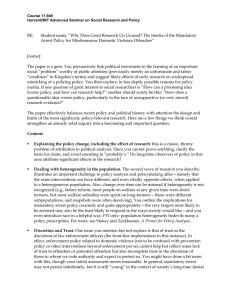

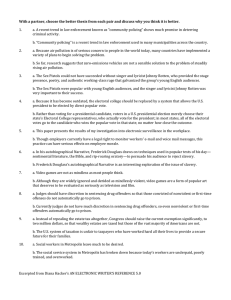

Eric Holder’s Recent Curtailment of Mandatory Minimum Sentencing, Its Implications, and Prospects for Effective Reform I. I n t r o d u c t io n On August 12, 2013, United States Attorney General Eric Hold­ er announced that it was time to “refine our charging policy regard­ ing mandatory minimums for certain nonviolent, low-level drug of­ fenders.”1 This announcement was prompted, in part,2 by the recent Supreme Court decision of Alleyne v. United States, which made clear that “any fact that increases the statutory mandatory minimum sen­ tence is an element of the crime that must be submitted to the jury and found beyond a reasonable doubt.”3Thus, “for a defendant to be subject to a mandatory minimum sentence, prosecutors must ensure that the charging document includes those elements of the crime that trigger the statutory mandatory minimum penalty.”4 While in the past a prosecutor could charge an offender with a mandatory mini­ mum without having to prove to a jury the elements triggering that mandatory minimum, now federal prosecutors’ charging decisions play a heightened role in “whether a defendant is subject to a manda­ tory minimum sentence.”5 In light of this information, Elolder has made a prime goal of “ensurfing] that our most severe mandatory minimum penalties are reserved for serious, high-level, or violent drug traffickers.”6 In order to accomplish this goal, Holder has directed federal prosecutors to 1. Att’y Gen. Memorandum from Eric Holder to the United States Attorneys and As­ sistant Attorney General for the Criminal Division 1 (Aug. 12, 2013) [hereinafter HOLDER M e m o r a n d u m ], 2. Eric Holder’s reference to Alleyne may serve as the pretense for changing charging policy, but, in reality, there has always been prosecutorial discretion to seek or not seek a man­ datory minimum sentence. See id. 3. Id. (citing Alleyne v. United States, 133 S.Ct. 2151, 2158 (2013)). 4. Id. 5. Id. 6. Id. 271 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw \V ol 29 conduct an individualized assessment of each offender, considering, in particular, (1) whether his or her offense involved the use or threatened use of violence, (2) whether the offender is a leader in a criminal organization or has significant ties to a criminal organiza­ tion, and (3) whether the offender has a significant criminal history, which “may be evidenced by three or more criminal history points but may involve fewer or greater depending on the nature of any pri­ or convictions.”7 This comment will address the motives behind Eric Holder’s an­ nouncement and its potential to resolve the problems associated with mandatory minimums. While, on the whole, the change seems likely to resolve many of the current criticisms of mandatory minimum sen­ tences, continued reliance on prosecutorial discretion will perpetuate disparity in sentencing and will also undermine Congress’ goal in creating the U.S. Sentencing Commission. Certainly Holder’s deci­ sion is a step in the right direction but, ultimately, the problems cre­ ated by mandatory minimum sentencing would best be resolved by Congress, rather than the Attorney General. II. W hy D oes E r ic H o l d e r ’s Announcem ent C ome N ow ? When all-American basketball player Len Bias was pronounced dead on June 19, 1986, the nation was left in shock.8 Only the day be­ fore, Bias was made the number two NBA draft pick by the Boston Celtics.9 At age 22, Bias was in top physical condition and yet, in the pre-dawn hours of June 19, he collapsed in his dormitory suite and within two hours had passed away.10 The culprit? A cocaine over­ dose.*11 During the mid-1980s the crack cocaine epidemic plagued the nation. First imported from the Bahamas around 1983,12 crack is a 7. Id. at 2. 8. Keith Harriston & Sally Jenkins, Maryland Basketball Star Len Bias is Dead at 22, WASH. P o s t , June 20, 1986, at Al, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp- srv/sports/longterm/memories/bias/launch/biasl.html. 9. Id. 10. Id. 11. David Nakamura & Mark Asher, 10 Years Later, Bias’s Death Still Resonates, WASH. POST, June 19, 1996, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wpsrv/sports/longterm/memories/bias/launch/biasl9.html. 12. Evan Thomas, America’s Crusade: What is Behind the Latest W ar on Drugs, TIME, 272 271] Eric Holder boiled down, crystalline form of cocaine which is not only cheaper, but more addictive than its powder counterpart.13 In 1986 this “rela­ tively new phenomenon” hit major cities like New York, Miami, and Los Angeles in a big way. For instance, over the course of one month the NYPD seized 45,000 crack pipes.14 In Florida, burglary rates in­ creased by 30 percent in 1986, which corresponded with an 80 per­ cent increase in cocaine arrests.15 In Los Angeles, the crack epidemic left broken homes in its wake and contributed to the growth of noto­ rious gangs like the Bloods and Crips.16 The crack epidemic not only caused a rise in crime rates and personal tragedy but also cost em­ ployers an estimated $33 billion in lost productivity, absenteeism, and higher accident rates by 1986.17 The effects of the crack epidemic caught the public’s attention and the “war on drugs” became a “regu­ lar feature on the nightly news and front pages.18” The crack epidemic and the shocking death of Len Bias led to die expedited passage of the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986.19 The Act es­ tablished the basic framework of mandatory minimum penalties ap­ plicable to federal drug offenses.20 For instance, the Act imposed a mandatory minimum sentence of five years for possession with intent to distribute one of the following: 5 grams of cocaine base (common­ ly called “crack” or “rock cocaine”), 500 grams of cocaine, 100 grams of heroin, or 100 kilograms of marijuana.21 Correspondingly, a man­ datory minimum of 10 years would be imposed for possession of 50 grams of crack, 5 kilograms of cocaine, 1 kilogram of heroin, or 1000 kilograms of marijuana.22 T he idea behind these mandatory mini­ mum sentences was simple: drug offenders’ sentences would correSept. 15,1986, at 60, 63. 13. Id. 14. Id. 15. Id. 16. See CRIPS AND BLOODS: M ade in America (Quincy Jones III & Steven Luczo 2008). 17. Thomas, supra note 12, at 60. 18. Id. at 61. 19. U.S. Sentencing C omm ’n , Report t o th e C ongress : Mandatory Minimum P enalties in th e Federal C riminal J ustice System 23 (2011) [hereinafter 2011 Report t o C ongress]. 20. Id. 21. Anti-DrugAbuse A ctof 1986, Pub. L. No. 99-570, §1002, 100 Star. 3207. 22. Id. 273 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw [Vol. 29 spond to the amount of drugs found in their possession.23 Fewer drugs meant less time, more drugs or repeated offenses meant more time.24 Mandatory minimums for drug offenders presented liberal and conservative legislators with a rare win-win scenario: liberals believed mandatory minimums would lead to less disparate sentencing on the part of federal judges (especially against minorities), while conserva­ tives appreciated the “tough on crime” nature of the new penalties.25 Additionally, in the wake of a rise in violent crime and the crack epi­ demic, the electorate’s fear would be alleviated.26 In its haste to ap­ pease constituents, Congress made the questionable decision of pass­ ing the Act without holding any hearings or producing any reports.27 By the early 1990s there were approximately 100 separate federal mandatory minimum penalty provisions relating to offenses ranging from drug possession to financial crimes.28 This harsher brand of sen­ tencing, however, was soon met with widespread criticism.29 In 1993, due to concern that the mandatory minimums were unfairly affecting low-level drug offenders, Senator Ted Kennedy introduced a bill to “recapture the goals of sentencing reform.”30 This proposal would come to be known as the “safety valve.” T he provision allowed feder­ al judges to avoid imposing the mandatory minimum sentence if the offender had only one criminal history point under the federal sen­ tencing guidelines, did not cause or threaten death or serious injury 23. 2011 Report t o C ongress , supra note 19, at 24. 24. Prior to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, there were a few mandatory minimum sentences in place for drug offenses (like those committed near schools or with especially dan­ gerous ammunition) but the 1986 Act “set up a new regime of non-parolable, mandatory mini­ mum sentences for drug trafficking offenses that tied the minimum penalty to the amount of drugs involved in the offense.” U .S . SENTENCING COMM’N, SPECIAL REPORT TO THE CONGRESS: MANDATORY MINIMUM PENALTIES IN THE FEDERAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE Sy s t e m 8 (1991) [hereinafter 1991 REPORT TO CONGRESS], 25. Philip Oliss, Mandatory Minimum Sentencing.: Discretion, the Safety Valve, and the Sen­ tencing Guidelines, 63 U. ClN. L. REV. 1851, 1852-53 (1995); Suzanne Cavanagh & David Teasely, Mandatory Minimum Sentencing for Federal Crimes: Overview and Analysis, in Mandatory M inimum Sen ten cing : O verview and Background 4 (Lawrence W. Brinkley ed., 2003). 26. Oliss, supra note 25, at 1852-53; Cavanagh & Teasely, supra note 25, at 4. 27. 2011 R e p o r t t o C o n g r e s s , supra n o te 19, a t 23-2 4 . 28. 1991 Report to C ongress , supra note 24, at 10. 29. See 2011 Report t o C ongress , supra note 19,at29. 30. Id. at 34 (citing 139 Cong. Rec. 26, 484-85 (1993) (statement of Sen. Kennedy)). 274 271] Eric Holder in the offense, did not possess a firearm or other dangerous weapon in connection with the offense, and did not hold a leadership role in the offense.31 More recently, the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 in­ creased the amount of crack cocaine an offender must possess before triggering imposition of the 5 and 10 year mandatory minimum sen­ tences.32 Despite these changes, mandatory minimums continue to present a variety of problems. In his memorandum, Holder gave four reasons why charging pol­ icies involving mandatory minimums vis-a-vis low-level drug offend­ ers were in need of change. First, “mandatory minimum and recidi­ vist enhancement statutes have resulted in unduly harsh sentences.”33 Second, these statutes have also resulted in “perceived or actual dis­ parities that do not reflect our Principles of Federal Prosecution.”34 Third, long sentences have failed to “promote public safety, deter­ rence, and rehabilitation.”35 Fourth, “rising prison costs” must be lowered in order to divert spending to other criminal justice initia­ tives.36 The following sub-sections will specifically address the ways in which mandatory minimums resulted in the unduly harsh sentenc­ es and the disparities that have led up to Plolder’s policy change. A . Unduly Harsh Sentences Drug-related mandatory minimums were passed with the intent to punish kingpins and mid-level dealers.37 However, before long, an­ ecdotal evidence began to appear that brought into question the actu­ al effects of the new sentencing scheme. The mandatory minimums stripped federal judges of their ability to take into account anything but the amount of drugs in the possession of the defendant when passing a sentence.38 In fact, prior to 1994, the only means whereby 31. Id.; 18 U.S.C. § 3553(1) (2006). 32. 2011 REPORTTO C ongress , supra note 19, at 30. 33. H older M em orandum , supra note 1, at 1. 34. Id.; For the “Principles of Federal Prosecution” to which Holder refers, see UNITED STATES Atto rn eys ’ M anual tit. 9-27.00, available at http://www.justice.gov/usao/eousa/ foia_reading_room/usam/index.html. 3 5. HOLDER MEMORADUM, supra note 1, at 1. 36. Id. 37. 2011 Re p o r t t o C ongress , supra note 19, at 24. 38. See Oliss, supa note 25, at 1856. 275 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw \V ol 29 judges could depart from the mandatory minimum was when the government submitted a motion for leniency in light of the offender’s substantial assistance in the prosecution of others.39 In essence, man­ datory minimums tied the judges’ hands. This limitation of judicial discretion, when combined with harsh punishments and sympathetic defendants, led many judges to describe such cases as “the worst of [their] career.”40 In a recent debate between Federal District Court Judge Stanley Sporkin and Congressman Asa Flutchinson, Sporkin highlighted the role limited judicial discretion plays in unduly harsh sentences.41 He specifically recounted how a mother of nine was arrested along with a drug kingpin for converting regular cocaine into crack cocaine for sale.42 The district court sentenced the kingpin to twenty years in prison; the mother would have been subject to a ten year mandatory minimum.43 The district court judge, however, decided that a ten year sentence was “too long” for a mother of nine and instead sen­ tenced her to three years imprisonment.44 While serving those three years, her case was appealed by the prosecution to the circuit court which held the sentence had been improper. By the time the circuit’s decision came down, the mother had served her three-year sentence and was completely rehabilitated.45 Nevertheless, she was sent hack to prison to complete her ten year mandatory minimum sentence.46 Fourth Circuit Judge Andre M. Davis has also expressed concerns about mandatory sentencing’s harsh nature. In a 2011 article pub- 39. Id; T he prosecution could also lower the charge as part of a plea deal, but this did not affect the judge’s obligation to follow the mandatory minimums where a charge required their implementation. 40. Nathan Greenblatt, How Mandatory Are Mandatory Minimums? How Judges Can Avoid Imposing Mandatory M inim um Sentences, 36 AM. J. CRIM. L. 1, 4 (2008) (citing Lance Cassack & Milton Heumann, Old Wine in New Bottles: A Reconsideration o f Informing Jurors About Punish­ ment In Determinate- and Mandatory-Sentencing Cases, 4 RUTGERS J. L. & PUB. POL’Y 411, 411 (2007)). 41. Judge Stanley Sporkin v. Congressman Asa Hutch, Mandatory M inimums in Drug Sentencing: A Valuable Weapon in the W ar on Drugs or■a Handcuff on Judicial Discretion?, 36 Am . C rim . L. R ev . 1279, 1284 (1999). 42. Id.; see United States v. Walls, 70 F.3d 1323 (D.C. Cir. 1995). 43. Sporkin, supra note 41, at 1284. 44. Id. 45. Id. 46. Id. 276 271 ] Eric Holder lished in the Baltimore Sun, Judge Davis related the story of Tony Allen Greg, whose life sentence Judge Davis had been obligated to uphold .47 Tony Allen Greg was “a drug abuser and occasional dealer, a lOth-grade dropout and petty criminal. ” 48 Greg’s life was marked by abuse and instability.49 Eventually, he had resorted to selling small amounts of cocaine out of a hotel in Richmond .50 W hen he was ar­ rested and tried, the trial court was statutorily bound to sentence him to life in prison, since this was his third drug-related felony and man­ datory minimums increase in severity with repeated offenses.51 Greg was neither a parent of nine children, nor an ideal citizen by any stretch of the imagination. Still, Judge Davis felt strongly that neither was he such a threat to society that he deserved the same penalty re­ served for murderers .52 When considering the consequences of mandatory minimums, however, the overall effect must be viewed, and not merely the hor­ ror stories. As Representative Asa Hutch said, “it will rip your heart out if you look at specific instances of conduct”; rather, the entire impact on society must be taken into consideration .53 This is especial­ ly true when assessing whether mandatory minimums have led to an overall problem of “unduly harsh” sentencing. According to the United States Sentencing Commission, lowerfunction offenders are convicted less often, per capita, than higherfunction offenders.54 Furthermore, lower-function offenders are also subject to mandatory minimums less often, per capita, than higherfunction offenders (see figure) . 55 47. Andre M. Davis, Mandatory Minimum Sentences Impede Justice, BALTIMORE SUN, Dec. 8, 2011, available at http://artides.baltimoresun.com/2011-12-08/news/bs-ed-sentencing20111208_l_mandatoiy-minimums-sentences-mandatory-term. 48. Id. 49. Id. 50. Id. 51. Id. 52. Id. 53. Sporkin, supra note 41, at 1285-86. 54 2011 REPORT TO CONGRESS, supra note 19, at 167 (High-Level Supplier/Importer offenders were convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty in 82.8 % of the cases, while Street-Level Dealer offenders were convicted of such a statute in 65.5 % of the cases. Only two functions—Courier and Mule—were convicted of an offense carrying a manda­ tory minimum penalty in less than half of the cases, 49.6% and 43.1% respectively.) T he terms “lower-function” and “higher-function” are not meant to be terms of art or strict designations; 277 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw [Vol. 29 Figure 8-9 Percent of Offenders Convicted of an Offense Carrying a Drug Mandatory Minimum Penalty and Subject to a Mandatory Minimum Penalty by Offender Function Fiscal Year 2009 Sample Data SOURCE: US. Sanscai C to ia n , MO»n»ct>o«Djo6k Thus, per capita, lower-function offenders are actually subject to less harsh penalties than the higher-ups in the drug distribution chain. This would seem to support the idea that mandatory minimums are accomplishing their goal of punishing the “kingpins” ra­ ther than low-level offenders. Still, the Commission stated that the rather, these are meant to differentiate the more influential players in the overall drug distribu­ tion chain (like leaders or managers) from the less influential ones (like mules and couriers). 55. Id. at 168 fig.8-9. In its 2011 Report to Congress, the Sentencing Commission di­ vides offenders broadly into two groups: higher-function offenders and lower-function offend­ ers or more and less serious offenders. Looking at fig. 8-9, more serious offenders include Im­ porters, Leaders, Manufacturers, Wholesalers, Managers, and Supervisors; less serious offenders include the remainder: Street Level Dealers, Brokers, Couriers, and Mules. Accord­ ing to the report, some of these roles are defined, in part, by the amount of drugs found in the offender’s possession (for instance wholesalers are those who buy or sell at least 1 ounce of a drug but less than a kilogram). See id. at 168-170. A full list of definitions for each role can be found in the 2011 REPORT TO CONGRESS on pages 166-67. 278 2711 Eric Holder “current mandatory minimum penalties for drug offenses may apply more broadly than originally intended by Congress.”56 How could this be the case? There are at least two reasons. First, lower-function offenders such as couriers and street-level deal­ ers constitute 40.2% of drug offenders, while managers and supervi­ sors constitute only 1.1% of the offenders.57 Therefore, even though lower-function offenders are convicted less often and entitled to re­ lief more often, they still constitute a large population that must bear the burden of mandatory minimum sentences—not the kingpins.58 Second, the figure above hides the fact that some groups receive relief from mandatory minimum sentences at disproportionate rates. For instance, non-citizens, constituting 26.4% of those convicted un­ der a statute carrying a mandatory minimum, received relief from mandatory minimums more often than U.S. citizens (64.6% com­ pared to 40.3%).59 This is because non-citizens often qualify for the safety valve provision due to lower criminal history scores, as most do not have prior convictions in the United States; foreign convictions are not factored into their criminal history, or they may have engaged in uncharged criminal activity in a country with relatively weak law enforcement.60 Thus, while only a small portion of lower-function of­ fenders are ultimately subject to mandatory minimum sentences, what the above chart may not reflect is that those who must bear the burden of mandatory minimums are disproportionately U.S. citizens. While higher-function offenders are subject to mandatory mini­ mums more often than lower function offenders, these offenders con­ stitute only a small portion of the individuals actually being put in prison. In reality, it is the lower-function offenders—the couriers, street dealers, and mules—who constitute the bulk of those charged. It is true that lower-function offenders are often entitled to some form of relief, but non-citizens benefit more often than U.S. citizens from these mechanisms.61 In accord with Holder’s statement, statisti­ cal and anecdotal evidence shows that the mandatory minimum sen56. Id. at 351. 57. See id. at 167. 58. It is worth noting that, as of die 2011 REPORT TO CONGRESS, drug offenders con­ stituted 53.8% of the BOP population. Id. at 164. 59. Id. at 124 tbl. 7-1, 147. 60. Id. at 135, 160. 61. See id. 279 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw____________________________ [Vol. 29 tences have been “unduly harsh” on lower-function, U.S. citizen drug offenders. B. Disparities in Sentencing Disparities in sentencing and unduly harsh sentences are often connected. Disparate sentencing often leads to unduly harsh sentenc­ es for one group over another. This section will assess the more common disparities that plague mandatory minimum sentencing. In its 1991 report to Congress on mandatory minimums, the U.S. Sentencing Commission criticized this new sentencing scheme for having led to “disparity and discrimination [that] the Sentencing Re­ form Act, through a system of guidelines, was designed to reduce.”62 This inconsistency came in a variety of forms ranging from racial dis­ parity to geographic disparity. While some of the more heinous dis­ parities in mandatory minimum sentencing have been addressed, there remain “perceived or actual disparities” which Holder’s new policy aims to rectify.63 Traditionally, one of the most troubling inequalities that ap­ peared as a result of mandatory minimums was the disproportionate sentences applied to lower-function offenders versus their higherfunction counterparts. Under the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, Congress permitted one instance under which a judge could sentence offenders below the applicable mandatory minimum. This exception stated: “Upon motion of the Government, the court shall have the authority to impose a sentence below a level established by statute as minimum sentence so as to reflect a defendant’s substantial assistance in the investigation or prosecution of another person who has com­ mitted an offense.”64 This substantial assistance exception highlighted the government’s goal of breaking up drug rings and seeking out the infamous king-pins, but ironically, led to low level-offenders lan­ guishing in prison while better-connected, more serious drug dealers walked free.65 In his discussion of this phenomenon, known as “inverted sen­ tencing,” Philip Oliss recounted the particularly heartbreaking and illustrative anecdote of Nicole Richardson. During her senior year, Nicole made the mistake of dating Jeff Thompson, a drug dealer. 62. 63. 64. 65. 280 1991 Re po r t t o C ongress , supra note 24, at ii. H older Memorandum , supra note 1, at 1. 18 U.S.C. § 3553(e) (2006). Oliss, supra note 25, at 1858. Eric Holder 2711 W hen one of Thompson’s suppliers was caught by the DEA, he named Thompson whom the agents proceeded to call, under the guise of being interested in purchasing drugs. Nicole, making her second mistake, picked up the phone and told the agents how to con­ tact Thompson for purchase. After leaving for college, Nicole was ar­ rested for conspiracy to possess with intent to distribute LSD. She received ten years in prison, while Jeff Thompson, who was able to assist the prosecution (presumably by providing information about others in the distribution chain), served only five years. This inverted sentencing, or “cooperation paradox” allowed “knowledgeable and, therefore, highly culpable offenders to escape the mandatory sen­ tences, while less culpable actors receive [d] the harsh penalties.66” Numerous occurrences such as Nicole’s eventually led to the passage of the safety valve provision which allows for downward departures from the mandatory minimum sentence where an offender has little to no criminal history.67 The second major source of disparity that long afflicted mandato­ ry minimum sentencing was the differential punishments associated with possession of crack cocaine versus powder cocaine.68 The AntiDrug Abuse Act of 1986 essentially codified the principle that one ounce of crack cocaine was the equivalent of one hundred ounces of powder cocaine. Thus, “possession with intent to distribute 50 grams (less than 2 ounces) of crack cocaine resulted in a 10-year mandatory sentence, while it would take 5000 grams (approximately 11 pounds) of powder cocaine to generate the same mandatory minimum.”69 This extreme response to the danger of crack cocaine was fueled by the crack epidemic and the earlier mentioned, highly publicized co­ caine overdose of Len Bias.70 O f course, it was only later discovered that Bias had died from powder—not crack—cocaine.71 66. Id. at 1863-64. This is not to say that the use of cooperating defendants is undesira­ ble. Indeed, cooperating defendants are often necessary for prosecution. Rather, this example simply highlights the cooperation paradox, which was, no doubt, a factor in Holder’s an­ nouncement. 67. Id. at 1861. 68. Erik Luna & Paul G. Cassell, Mandatory Minimalism, 32 CARDOZO L. REV. 1, 4 ( 2010). 69. Id. 70. Id. at 25. 71. Id. 281 B Y U J ournal of \Vol 29 P ublic L aw N ot only was the development of the crack-powder differential uninformed due to the expedited nature of the Act,72 it also had ineq­ uitable racial effects. Demographically, about half of all powder co­ caine offenders are Hispanic, roughly a quarter are Black, followed by W hite offenders.'3 However, over three quarters (78.6%) of crack co­ caine offenders are Black, followed next by Hispanics who constitute 13% of all offenders.74 This trend is reflected in sentencing: 78.7% of those subject to a mandatory minimum for crack-related offenses are Black.75 In response to the criticism of the crack-powder ratio, the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010 lowered the crack-powder cocaine disparity to an 18:1 ratio and eliminated the mandatory minimum for simple possession altogether.76 Despite the Fair Sentencing Act and the pas­ sage of the safety valve, mandatory minimums have continued to pre­ sent issues of disparity. Demographically, Blacks are denied relief from mandatory minimums more often than any other race.77 In fact, data suggests that the passage of the safety valve—which has benefi­ ted so many lower-function offenders—has actually widened the chasm between the rate at which Black offenders and those of other races receive relief.76 Blacks continue to be subject to both mandatory minimums and to receive enhanced penalties at a higher rate than other races.79 While mandatory minimums have achieved one goal of being tough on crime, they have failed to address the demographic disparity for which they were created. III. T he L ik e l y H E ffects of t h e arsh a n d D N is p a r a t e ew P o l ic y o n U nduly S e n t e n c in g Holder is not the first person to promote changes that would benefit lower-function offenders. The safety valve provision, enacted in 1994 as part of the Violent Crime Control Act, was meant to give a degree of discretion back to judges to ensure that sentencing was 72. 73. 74. 75. 76. Id. 2011 REPORTTO C ongress , supra note 19, at 187. Id. at 191. Id. at 192 tbls. 8 & 7. Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111-220, 124 Stat. 2372; Luna & Cassell, supra at note 68 4. 77. See 2011 REPORT TO C ongress , supra note 19, at 263. 78. See infra notes 79-82 and accompanying text. 79. 2011 REPORTTO C ongress , supra note 19, at 267. 282 2711 Eric Holder “tough but fair” on non-violent, first-time drug offenders.80 In sub­ stance, the safety valve provision ensures that defendants who have little to no criminal history (one criminal history point or less); who did not use or threaten violence in connection with the offense; and who were not organizers, leaders, or planners in the offense may avoid having the mandatory minimum imposed upon them.81 Holder’s policy and the safety valve are remarkably similar: both create a mandatory minimum exception for lower-function offenders, both are based-on criminal history points, and both require that the offense be non-violent. In many ways, Holder’s policy is little more than an expansion of the safety valve by the Executive Branch. W ith that in mind, an assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of the safety valve will help demonstrate the likely effects of this new policy on harsh and disparate sentencing. T he safety valve has been critiqued because it fails to address the problem of sentencing cliffs and misplaced equality.82 Sentencing cliffs refer to the event in which one offender, having 500 grams of a drug will receiving an extremely different sentence from another, similarly situated offender with only 499 grams of the same drug.83 This idea—that offenders should be judged solely on the amount of drugs in their possession and nothing else—is referred to as mis­ placed equality.84 The safety valve did not eliminate sentencing cliffs, nor misplaced equality on the whole, but it did curb its effects for lower-function offenders.85 If an offender qualified for the safety valve, it did not matter how many drugs were in his possession, he could still avoid the mandatory minimum sentence.86 The only prob­ lem was that to qualify for the safety valve, an individual had to have little to no criminal history. Even multiple minor infractions would lead to disqualification. Holder’s new policy essentially expands the access offenders will have to the safety valve. This means that, in more cases, judges will be able to take more into account than the amount of drugs in the offender’s possession and create more indi80. Oliss, mpra note 25, at 1883 n.258. 81. 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) (2006). 82. Oliss, supra note 25, at 1889-90. 83. See id. at 1889. 84. Id. at 1860. 85. Id. at 1890. 86. This is not to say that the amount of drugs in the offender’s possession would not ultimately affect his sentence under the Sentencing Guidelines. In fact, the Guidelines still pri­ marily base sentencing ranges on the amount of drugs in a criminal’s possession. 283 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw ______________________________ [Vol. 29 vidualized and just sentences without the perils of misplaced equality and dramatic cliff effects. For all its successes, perhaps the most unfortunate effect of the safety valve has been its disparate treatment of diverse races. Prior to the passage of the safety valve provision, Black and Hispanic offend­ ers received relief from mandatory minimums at a similar rate (34.3% and 34.2% respectively).87 After the enactment of the safety valve, however, “the rate at which Hispanic, White, and Other Race of­ fenders obtained relief from a mandatory minimum penalty increased appreciably while the rate for Black offenders did not.”88 For in­ stance, in fiscal year 2010, White offenders received relief at 46.5% and Hispanics at 55.7%.89 Black offenders, on the other hand, re­ ceived relief at a rate of 34.%.90 This trend carries over into drugrelated offenses as well. Hispanic offenders convicted of a drug of­ fense carrying a mandatory minimum receive safety valve relief 46.3% of the time, while shockingly, Black offenders receive relief only 14.4% of the time. 91 This disparate sentencing stems from the fact that over 75% of Black drug offenders have a criminal history score too high to qualify for the safety valve provision.92 Because non­ citizen offenders (many of whom are presumably Hispanic) do not have their foreign convictions calculated into their criminal history under the Guidelines Manual, they are therefore often qualified to benefit from the safety valve.93 The clear disparity in the rates at which Black drug offenders are subjected to mandatory minimums versus those of other races is stunning. Such discrepancy gives credence to the argument that the criminal justice system serves as a new form of Jim Crow laws.94 Plolder’s policy is likely to help alleviate this discrepancy. It will allow offenders the same benefits that exist under the safety valve while broadening the scope of those benefits. Where under the safety valve only those with one criminal history point were qualified for relief, 87. See 2011 REPORTTO CONGRESS, supra note 19, at 133. 88. Id. 89. Id. 90. Id. 91. Id. at 159. 92. Id. at 160. 93. Id. 94. See MICHELLE ALEXANDER, T H E N E W jlM CROW: MASS INCARCERATION IN THE Ag e o f C olorblindness (2010). 284 Eric Holder 2711 now offenders with two criminal history points (or potentially more) may receive relief.95 There is no doubt that many Black offenders, who under the old regime would have been ineligible for relief, will be benefitted by this new policy.96 However, it is yet to be seen to what degree this new policy will help ensure that Black offenders re­ ceive mandatory minimum relief at a rate more comparable to that of offenders of other races. While Holder’s new policy may lessen the application of unduly harsh sentences through relaxing the qualifications to receive relief, it may have the undesirable effect of creating greater disparity and un­ predictability in sentencing. Consider the racial disparity discussed above. The new policy seemingly aims to lessen the disparity between Black offenders’ sentences and that of other races by allowing prose­ cutors greater leeway in choosing when to charge mandatory minimums and by allowing judges to look at each offender individually. Ironically, one of the very reasons for the implementation of manda­ tory minimums was fear that federal judges had too much discretion, discretion that led to unpredictable and disparately harsh sentencing on minorities.97 Unfortunately, it is likely that the increase in prose­ cutorial and judicial discretion that will result from Holder’s policy change will lead to greater disparity in federal sentencing. Experience shows that when judges are given greater discretion, greater sentencing disparity will result. In 1987, judicial discretion was hemmed in by the creation of the Federal Sentencing Guidelines which established the bounds beyond which a judge could not ven­ ture in the context of sentencing.98 In 2005, however, in United States v. Booker, the Supreme Court held that the provision that made the Federal Sentencing Guidelines mandatory was unconstitutional and had to be excised, thus rendering the Guidelines advisory.99 Since the shift from mandatory to advisory Guidelines, “[t]he Department of 95. See HOLDER MEMORANDUM, supra n o te 1, a t 2. 96. Holder has referred to the disparity that exists between W hite and Black offenders’ sentences as “shameful” and has recendy ordered a group of U.S. Attorneys to study sentencing disparities and create recommendations on how to address them. PBS Newshour, Watch Attor­ ney General Eric Holder Announce Major Changes to Criminal Justice System, YOUTUBE (Aug. 12, 2013), http://www.youtube.com/watchPvsoteyZs8Yw4. 97. CAVANAGH & TEASELY, supra note 25, at 13; David M. Zlotnick, The War Within the War on Crime: The Congressional Assault on Judicial Sentencing Discretion, SI SMU L. Rev. 211, 216(2004). 98. CAVANAGH & TEASELY, supra note 25, at 4, 13. 99. United States v. Booker, 543 U.S. 200, 245, 266-67 (2005). 285 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw [Vol. 29 Justice has noted that sentencing disparities have increased . . . be­ cause for ‘offenses for which there are no mandatory minimums, sen­ tencing decisions have become largely unconstrained as a matter of law. ” ’100 Specifically, the difference in sentence length between Black male offenders and W hite male offenders has “increased steadily since the passage of Booker.”m Judicial discretion, however, is not the only concern. Holder’s decision will also give individual prosecutors the responsibility of choosing when to seek mandatory minimums. This may also result in increased sentencing disparities. I V . T h e P r o b l e m s A s s o c ia t e d w it h M a n d a t o r y M in im u m s are B e s t R eso lv e d by C o n g r ess A. Prosecutorial Discretion and Inequitable Sentencing Eric Holder’s announcement cedes more prosecutorial discretion to the United States Attorneys, which will adversely impact predicta­ bility and lead to more disparity in sentencing. An enactment by Congress expanding the current safety valve provision would avoid this effect and thus evade the problems inherent in prosecutorial dis­ cretion . 102 As discussed earlier, Holder’s announcement will likely lead to an increase in sentencing disparity. Angela Davis, a professor at the Washington College of Law, has hypothesized that a lack of account­ ability is central to the issue of disparity. 103 If large scale changes as­ sociated with sentencing were left to the discretion of Congress, the likelihood of disparity would diminish . 104 There is no doubt that discretion is an important prosecutorial tool. In the past few decades there has been a proliferation of federal criminal statutes. 105 Increasing amounts of criminalized activity in­ creases the importance of prosecutorial discretion. Bound by the de­ mands of limited resources, it is up to prosecutors to choose to prose100. 201 1 REPORT t o C o n g r e s s , supra note 19, at 8 5 -8 6 (citing Prepared Statement of Sally Quillian Yates, U.S. Attorney, N orthern District of Georgia, to the Commission, at 7 (May 27, 2010) (on behalf of the U.S. Department of Justice)). 101. Id. at 347. 102. See 2011 REPO RTTO CONGRESS, supra n o te 19, at 368. 103. See generally ANGELA J. DAVIS, ARBITRARYjUSTICE (2007). 104. Id. 105. Id. at 93. 286 2711 Eric Holder cute cases that will effectively carry out the goals of law enforce­ m ent . 106 T here are simply too many laws and too many offenders for prosecutors to charge every case. While prosecutorial discretion plays an im portant role in our sys­ tem of law enforcement, it can and does lead to inconsistency in sen­ tencing . 107 Unlike federal judges, whose discretion was limited by the creation of the sentencing guidelines and mandatory minimum sen­ tences, federal prosecutors have enjoyed “wide latitude” in their dis­ cretion on every subject from when to charge to the length of a de­ fendant’s sentence . 108 In his August memorandum, H older further broadened this latitude by disseminating to individual U.S. A ttor­ ney’s Offices the power to choose what mandatory minimums to charge based on “individualized assessments . ” 109 These “assessments” take into consideration whether the offender has a “significant crimi­ nal history,” which H older suggests is three criminal history points or more, but which “may involve greater or fewer [points]” depending on the nature of the prior convictions . 110 This highly discretionary standard will inevitably lead to less predictable, more disparate sen­ tences for offenders across the United States. It has been suggested that the reason why prosecutorial discretion results in disparity is that prosecutors are not held accountable for their decisions . 111 As Angela Davis states in her book, Arbitrary Jus­ tice, The lack of enforceable standards and effective accountability to the public has resulted in decision-making that often appears arbi­ trary . . . These decisions result in tremendous disparities among similarly-situated people, sometimes along race/class lines. The rich and white, if they are charged at all, are less likely to go to prison than the poor and black or brown—even when the evidence of criminal behavior is equally present or absent. 112 106. Id. at 13—14. 107. T he C onstitution P roject , P rinciples for D esign and Reform of Sentencing Systems: A Background Report 26,27 (May 13, 2010) (“[T]he existence of mandatory minimum sentences tied to conviction of particular offenses permits manipulation of sentences through differential prosecutorial charging and plea bargaining policies. Such manip­ ulation undercuts the objective of reducing disparity.”). 108. CAVANAGH & TEASLEY, supra note 25, 4—5 n,8. 109. H older M emorandum , supra note 1, at 2. 110. Id. 111. See DAVIS, supra note 47, at 15—16. 112. Id. at 16. 287 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw [Vol. 29 Because prosecutors are not beholden to the standards, supervision, and review that other officials are, it is easier for them to make arbi­ trary choices based on “deep-seated, unconscious” views which lead to disparity. 113 Illustrative of this principle is the story of David McKnight. McKnight was a white, twenty-five-year-old Georgetown student and part-time bartender . 114 He lived with John Nguyen, a fifty-fiveyear-old Vietnamese immigrant who paid rent to McKnight for the privilege of sleeping in his walk-in closet. 115 One evening, McKnight held a party at his apartment and asked Nguyen to leave. 116 A fight ensued, and, after the partygoers had left, McKnight attacked Ngu­ yen with a machete, almost hacking him in half. 117 Nguyen was able to stagger into the street, but, “ironically, the first ambulance on the scene picked up McKnight [who was covered in his victim’s blood], leaving Nguyen to die . ” 118 Following the crime, the local prosecutor (who was also white) reached out to McKnight’s defense attorney and suggested that McKnight would have a strong case for self-defense and asked the defense counsel to submit a list of witnesses who could testily as to McKnight’s peaceful reputation, and Nguyen’s reputa­ tion for violence. 119 The prosecutor proceeded to present these wit­ nesses to the Grand Jury, which voted not to indict McKnight. 120 McKnight would later be heard to brag about getting away with murder . 121 This anecdote, while a very dramatic example, illustrates the great latitude that prosecutors at each level of government have to try crimes. The same discretion that is so important in the administra­ tion of justice can just as quickly undermine it. There was no evi­ dence in the case of McKnight that race or class were taken into ac­ count; however, as Davis points out, a similarly-situated Black defendant was treated entirely differently by the same prosecutor’s 113. Id. at 17. 114. Id. at 19. 115. Id. 116. Id. at 19-20. 117. Id. at 20. 118. Id. 119. Id. 120. Id. 121. Id. at 19. Upon news that he would not be indicted, McKnight actually went to a bar, bought a Dom Perignon, and announced “I killed someone and got away with it!” Id. 288 2711 Eric Holder office. 122 The Black defendant, Daniel Ware, was a manual laborer in the D.C. area who had been threatened by a local gang member known to carry guns and who had a reputation for violence. 123 Fearful for his life, Ware carried a knife for protection . 124 When this gang member cornered Ware in an alley, threatened him, and began to draw something from his jacket, Ware stabbed the gang member once in the chest; the gang member died that evening. 125 Unlike in McKnight’s case, “[t]he prosecutor never offered to present exculpa­ tory evidence to the Grand Jury on W are’s behalf. Ware was indicted for first-degree murder.” 126 From the facts Davis provides, the dis­ parate approach in prosecuting these two defendants cannot easily be explained. W hether race, class, or even the relationship that the pros­ ecutor had with opposing counsel are factors that will never be known . 127 W hat is clear is that prosecutors are human. Their deci­ sions concerning who and how to prosecute are influenced by a wide variety of factors, and questioning their decisions is often impossible. The inconsistency in sentencing that naturally results from such a system will only be heightened under Plolder’s new policy granting greater latitude to individual U.S. Attorneys and their assistants. It is for this reason that major decisions relating to federal sen­ tencing are best left to Congress, which, unlike an appointed U.S. At­ torney, is directly answerable to the American people for its deci­ sions. While the changes announced by Flolder seem generally beneficial and in keeping with the recommendations given to Con­ gress by the U.S. Sentencing Commission, 128 the Attorney General has enacted a major change in the U.S. Sentencing system for which voters cannot hold him responsible. 129 122. Id. at 21. 123. Id. at 20. 124. Id. at 21. 125. Id. 126. Id. i t 22. 127. See id. at 21-22. 128. See 2011 REPORT TO CONGRESS, supra note 19, at 368 (“Congress should consider marginally expanding the safety valve at 18 U .S .C . § 3553(f) to include certain non-violent of­ fenders who receive two, or perhaps three, criminal histoiy points under die guidelines.”). 129. It should be noted that, in theory, voters could hold the President responsible for the actions of the Attorney General. In practice, this is a weak check on the Attorney General. 289 B YU J o u r n a l o f P u b l i c L a w ____________________________________ [ V o l. 29 B. Congress is Better Suited to Alter Mandatory Minimum. Sentencing The congressional intent behind the creation of the U.S. Sen­ tencing Commission is undermined by Holder’s new policy. This is not to say that the policy is in any way unconstitutional. It is im­ portant, however, to recognize that Congress has specifically taken steps to ensure that it has control over sentencing and that the Attor­ ney General’s role is limited. Congress, in creating the U.S. Sentencing Commission, has ex­ pressly required that amendments to the Sentencing Guidelines be brought to its attention and are subject to its disapproval or modifica­ tion.130 In this way, the Sentencing Commission is limited in its rulemaking power. The Sentencing Commission is not allowed to unilat­ erally change the Guidelines; rather, it is tasked with creating pro­ posals that Congress has six months to accept through inaction, or reject or modify through a Congressional Act.131 While its rulemaking capability is limited, Congress has endowed the Sentencing Commission with significant research powers such as the ability to call hearings; establish a research and development program; utilize the equipment, personnel, and information of federal, State, local, and private agencies; and request information from other federal agencies and the judiciary as it so requires.132 This extensive access to resources, combined with the Congressional check on changes to the Guidelines, make clear that Congress intended for changes in federal sentencing to be well-informed and subject to its supervision. It is also notable that, in forming the Sentencing Commission, Congress granted the Attorney General great input, but little deci­ sion-making power in its affairs.133 'Fide 28 Section 991 of the United States Code establishes the Sentencing Commission as a body within the Judicial Branch and provides that the President is to appoint the members of the commission with the advice and consent of the Sen­ ate.134 The statute requires that the Commission be bipartisan, in­ clude at least three federal judges, and that the Attorney General or 130. 28 U.S.C.A. § 994(d) (West 2010). 131. Id.-, Federalist Soc’y Teleforum , Is Eric Holder Right About Mandatory Minimums?, FEDERALIST S o c ’y (Sept. 3, 2013), http://www.fed-soc.org/publications/detail/is-eric-holderright-about-mandatory-minimums-podcast. 132. 28 U.S.C.A. § 995 (West 2010). 133. 28 U.S.C.A. § 991(a) (West 2010). 134. 28 U.S.C.A. § 991 (West 2008). 290 271] Eric Holder his or her designee act as a non-voting member of the Commission. 5 This curious organization makes clear a few principles. First, the Sentencing Commission is meant to reflect all three branches of gov­ ernment; for this reason all three branches play a role in its for­ mation. This is fitting since the laws under which offenders will be tried and sentenced are created by Congress, enforced by the Execu­ tive, and adjudicated by the Judiciary. The second principle is that, like the federal government itself, no one branch should have too much power. Even though the Executive may choose the members, Congress has defined the composition of the committee and the roles and qualifications of its members. It is as though Congress were em­ phasizing that just and effective sentencing is and ought to be a group effort between all branches—utilizing the wisdom and experience that each branch has to offer. Third, sentencing research and pro­ posals should be the product of a bipartisan effort. Fourth, the Attor­ ney General should be able to influence sentence reform, but only in an advisory capacity. Holder’s adoption of a new charging policy, which calls for the circumvention of congressionally passed mandatory minimums, 136 undermines the ideals imbedded in the Sentencing Commission’s formation—it is a unilateral move by one branch of government that cannot be checked. Furthermore, it is a functional change that gives no indication of bipartisan participation. Lastly, it not only effectively gives the Attorney General a say in sentencing, but it also gives him the final say. This should give pause. Congress clearly intended that the commission charged with developing sentencing policy be subject to its supervision, and reflect the best judgment of all three branches of government. Perhaps this stems from the serious impacts of feder­ al sentencing on the lives of congressional constituents.13' Holder’s actions, while presumably well-informed, and constitutional, tend to undermine the goal of Congressional legislation and pave the way for less sagacious—but equally unreviewable—changes to sentencing in the future. 135. Id. 136. It is important to note that prosecutors have always had the capacity to charge or not charge mandatory minimums. However, Holder’s new policy is unique because it would make circumvention of the mandatory minimums applicable to lower-function offenders a regular practice. 137. See Federalist Soc’y Teleforum, supra note 131. 291 BYU J ournal of P ublic L aw |Vol. 29 Figure 7-8 Percent of Offenders Convicted of an Offense earnin g a Mandatory Minimum Penalty Who Were Relieved of the PenaltyFiscal Year 2010 ■ N o M tf AS S u b to ta l AssislaiMs White Black Hispanic Other iSafttv Valve Male Female B Sub Asst &$Y U.S. Son Citizen Citizen SOURCE. Vi. S— rt^ClM ilH n. 2010BraSt USSCmO As the passage of the safety valve demonstrates, Congress is capa­ ble of issuing clear and effective standards for federal sentencing. It is true, as has been seen, that the safety valve has not been a perfect tool. It has had an inequitable effect on minorities, allowing illegal immigrants to escape mandatory minimums, while rarely granting Black offenders the same privilege. Still, the safety valve has done a great deal to eliminate inverted sentencing, ensuring that less culpa­ ble drug offenders do not spend more time in prison than more knowledgeable and dangerous offenders. In fact, in fiscal year 2010, nearly half of all offenders convicted of a drug offense carrying a mandatory minimum were relieved due to either the safety valve or a substantial assistance motion (see figure below).138 Additionally, the safety valve is more predictable in the cause of disparity than prosecutorial discretion. Congress utilizes the Sentenc­ ing Commission for the purpose of ascertaining the most equitable, 138. 2011 REPORTTO C ongress , supra note 19, at 132; id. at 133, tbl. 7 & 8. 292 271] Eric Holder predictable, and effective sentencing methods . 139 While the safety valve has not been racially equitable, it is predictable, and it is easy and effective to implement because it requires a minimal amount of discretion at sentencing. The result of this has been what may best be labeled as “predictable disparity.” The Sentencing Commission has recognized that Blacks receive less relief under the current relief mechanisms, and it has also diagnosed the problem: Black offenders simply have higher criminal history scores than their counterparts . 140 W ith this knowledge, Congress is in a position to formulate a refined version of the safety valve which will ensure greater equity among races. Holder, no doubt frustrated by Congressional inaction, has adopted his own version of the safety valve which seeks to solve the problem of inequity, but at the cost of introducing the unpredictabil­ ity that will accompany the flexible, discretionary standards for pros­ ecutors set forth in his memorandum. Such prosecutorial discretion, combined with the increased judicial discretion that will come from charging mandatory minimums less frequently, may undermine Holder’s very goal of equity. While Congress’ enactment—the safety valve—suffers from “predictable disparity,” Holder’s policy may re­ sult in the even less desirable “unpredictable disparity.” In the event that Congress’ standards prove unjust, members of the Senate and House will be answerable to their constituencies. 141 While Eric Holder’s change will likely resolve many of the problems associated with mandatory minimum sentencing, it also places a great deal of emphasis on prosecutorial discretion which will likely lead to disparate results. Neither Holder nor the various U.S. Attorneys can truly be held accountable for the creation and implementation of a standard that will affect millions of Americans. Congress, which has placed a special emphasis on overseeing changes in federal sentenc­ ing, is better suited to implement major changes to mandatory mini­ mum sentences. C. Options Available to Congress If major changes in sentencing are to be left to Congress, how then should Congress approach the issue of mandatory minimums, 139. See 28 U.S.C.A. § 991(b)(1)(B) (West 2008). 140. 2011 Report t o C ongress, supra note 19, at 147. 141. This, of course, assumes that voters follow issues relating to criminal justice. While this may not have always been the case, recent issues relating to the costs of mass incarceration seems to have piqued public interest in the criminal justice system. 293 BYU J ournal of P ublic Law [Vol. 29 and how would it be different from Holder’s new policy? It seems abundantly clear that Holder’s new policy derives directly from the U.S. Sentencing Commission’s 2011 Special Report to Congress on mandatory minimums. In the Conclusions and Recommendations portion of the report, the Sentencing Commission stated that, “Con­ gress should consider marginally expanding the safety valve at 18 U.S.C. § 3553(f) to include certain non-violent offenders who receive two, or perhaps three, criminal history points under the guide­ lines.”142 It is surely more than mere coincidence that the new policy directly reflects this advice. Because the expansion of the safety valve is a recommendation that comes directly from the U.S. Sentencing Commission, it cannot be lightly ignored. In fact, Holder’s policy is laudable in its attempt to implement the ideals contained therein. However, were Congress to implement this advice, it could improve on Holder’s policy by cre­ ating a bright line rule. The Holder policy’s weakness stems from the degree of discretion it grants to prosecutors. It only suggests what constitutes a significant criminal history, leaving individual prosecu­ tors to decide (potentially arbitrarily) when to apply to mandatory minimum charges. Congress should implement a new safety valve that allows for non-violent offenders with a criminal history score of three or less and who played a minor role in the offense to be relieved of the man­ datory minimum. This bright line standard would curb prosecutorial discretion for charging mandatory minimums. It would also ensure that Black offenders receive the benefit of relief more often, and therefore more equitably when compared to other races. Consider the following data: In fiscal year 2010, 76.1% (n=4,738) of Black offenders who were convicted of an offense carrying a mandatory minimum penalty were in Criminal History Categories II-VI, which would disqualify them from consideration for the safety valve. By contrast, 47.6% (n=2,582) of W hite offenders, 33.6% (n=2,544) of Hispanic offend­ ers and 41.8% (n=226) of Other Race offenders were in Criminal History Categories II-VI.143 This suggests that the expanded safety valve would be more bene­ ficial to Black offenders than offenders of another race. This would 142. 2011 Re po r t t o C ongress , supra note 19, at 368. 143. Id. at 132. 294 2711 Eric Holder likely result in a more equitable rate of relief from mandatory minimums across the board . 144 Were Congress to implement this change, it would not alleviate the nation’s sentencing woes overnight. One glaring problem would still be increased judicial discretion, which, as noted earlier, is known to contribute to sentencing disparity. It seems however, that there is very little hope of escaping all forms of disparity which naturally re­ sult from human discretion. Mandatory minimums themselves prom­ ised to do away with disparity, but clearly that did not happen. This being the case, the nation—through Congress—must choose the de­ gree to which it will tolerate disparity. Placing greater discretion in the hands of federal judges while limiting prosecutorial discretion is preferable to Holder’s proposal which would increase both prosecu­ torial and judicial discretion. Judicial discretion is preferable to prosecutorial discretion for a variety of reasons. First, federal judges are often highly experienced. As Judge Sporkin said, it is irrational that the nation would give a “twenty five or thirty-year-old [United States Attorney] more discre­ tion than you’re giving a fifty-five-year-old judge who’s had a lot of jobs and has been through the system and thoroughly vetted . ” 145 Yet every day federal prosecutors make charging decisions that, in many ways, control the offender’s sentence. Holder’s policy would only further shift “discretion to prosecutors, who do not have the incen­ tive, training, or even the appropriate information to properly con­ sider a defendant’s mitigating circumstances at the initial charging stage of a case. ” 146 Second, federal judge’s decisions, unlike those of prosecutors, are made in public view. 147 “Justice Anthony Kennedy has observed that even though a prosecutor may act in good faith, the ‘trial judge is the one actor in the system most experienced with exer- 144. Enacting a safety valve expansion for the purpose of accommodating the criminal histories of one race may be viewed as a form of affirmative action in the realm of criminal sen­ tencing. However, the author would suggest that while individuals should be held accountable for their criminal past, where an entire race is found to have a higher criminal history than any other race, it is no longer a matter of individual culpability; it becomes a matter of societal cul­ pability. The author does not believe that one race should be punished for such societal short­ comings. 145. Sporkin, supra note 41, at 1288. 146. 2011 REPORT TO C o n g r e s s , supra note 19, at 96 (quoting Prepared Statement of James E. Felman, American Bar Association, to the Commission, at 12-13 (May 27, 2010)). 147. See id. at 97. 295 BYU J ournal of P ublic Law [Vol. 29 cising discretion in a transparent, open, and reasoned way.’”148 While federal judges are by no means infallible, their considerable experi­ ence and the open nature of their proceedings make them the prefer­ able choice when granting discretionary powers.149 Congress has been slow to act on the issue of mandatory minimums. Since the implementation of drug-related mandatory minimums in the mid-1980s there have been only two major enactments revisiting their effectiveness: the creation of the safety valve in 1994, and the minimizing of the ratio between crack and powder cocaine in 2010. Such inaction is frustrating in light of racial disparity and growing prison populations. Still, a congressional action that expands the safety valve would be preferable to Holder’s policy. Such an ac­ tion would reflect the will and wisdom of the three branches of gov­ ernment: it would be proposed by the bipartisan, multi-branch Sen­ tencing Commission, passed by Congress, and signed off on by the President. This would give the new sentencing policies greater validi­ ty in the public eye and allow Congress to answer for any shortcom­ ings. Furthermore, this system would minimize the danger of dispar­ ate sentencing by placing discretion primarily on the judges, rather than the prosecutors. V . C onclusion H older’s new policy represents a step in the right direction for sentencing drug offenders. First, its expansion of the safety valve is based on the well-researched findings and advice of the U.S. Sen­ tencing Commission. Second, it aims to lessen the problems of harsh and racially disparate sentencing often associated with mandatory minimums. The Commission’s advice, however, was not directed at the Attorney General; it was meant for Congress’ consideration for good reason. By taking the reins on the matter of sentencing reform, Holder may have undermined the very goal of diminishing disparate sentencing. The new policy places increased discretion on individual prosecutors to decide who will or will not face the mandatory mini­ mum sentence if convicted. The unreviewable, unexplained decisions 148. Id. (quoting Justice Anthony M. Kennedy, U.S. Supreme Court, Speech at the Amer­ ican Bar Association Annual Meeting (Aug. 9, 2003)). 149. This is not to say that prosecutors should be deprived of discretion. Prosecutors have the difficult task of setting law enforcement priorities and then implementing them through charging practices. Rather, the author merely contends that increased discretion on the matter of sentencing is better placed in the hands of the judiciary. 296 2711 Eric Holder of these prosecutors will inevitably result in disparities. This policy change should be disfavored because Congress is equally capable of implementing change which would result in less disparity. Nevertheless, Holder has acted within his constitutional capacity as Attorney General and the burden now lies upon Congress to exer­ cise its powers to redress the flaws in mandatory minimum sentenc­ ing for drug offenders. T aking the lead from Holder, Congress may implement a new, expanded version of the safety valve which would allow relief from mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders with a criminal history score of three or less. This bright line rule would limit prosecutorial discretion and shift discretion to judges whose decisions would be influenced by the Sentencing Guidelines and made in public view. While the new system would not be perfect, it would be preferable. And in the mercurial world of sentencing, where individual lives are in the balance, even small im­ provements should be embraced. Alan Dahl,J.D. Candidate 2015 297 Copyright of BYU Journal of Public Law is the property of Brigham Young University Law School and its content may not be copied or emailed to multiple sites or posted to a listserv without the copyright holder's express written permission. However, users may print, download, or email articles for individual use.