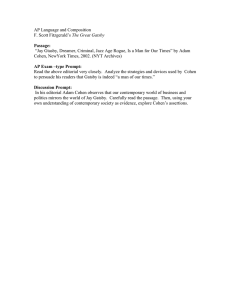

Looking Back at Cohen v. California A 40 Year Retrospective from (1)

advertisement