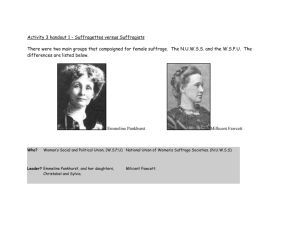

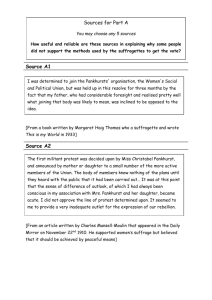

Women’s Suffrage movement in the UK Ilona: Women’s suffrage is the right of women by law to vote in national or local elections. Women were excluded from voting in ancient Greece and republican Rome, as well as in the few democracies that had emerged in Europe by the end of the 18th century. When the franchise was widened, as it was in the United Kingdom in 1832, women continued to be denied all voting rights. The question of women’s voting rights finally became an issue in the 19th century, and the struggle was particularly intense in Great Britain and the United States, but those countries were not the first to grant women the right to vote, at least not on a national basis. By the early years of the 20th century, women had won the right to vote in national elections in New Zealand (1893), Australia (1902), Finland (1906), and Norway (1913). In Sweden and the United States they had voting rights in some local elections. In Great Britain woman suffrage was first advocated by Mary Wollstonecraft in her book “A Vindication of the Rights of Woman” (1792) and was demanded by the Chartist movement of the 1840s. The demand for woman suffrage was increasingly taken up by prominent liberal intellectuals in England from the 1850s on. Ann: The first organised women’s suffrage movement began in 1866 in Manchester when women sought to be included in the extension of the franchise to more men in the UK. As a result of the failure of the political parties at that time, particularly the Liberal and The Conservative party, to act on these demands to extend the franchise to women the frustration increased among certain quarters of the wider suffrage movement. The women saw having access to political citizenship, having the right to vote would alleviate some of the everyday difficulties they experienced in their lives, so poor working conditions, low pay, lack of health care, all of these issues could be changed and were more likely to be changed. They strongly believed that if you had representation in the houses of parliament, their lives would change for the better. Ilona: In 1897, the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies was founded. They were known as the Suffragists. By 1910 MPs began to take notice and support the women’s suffrage and they have slowly came round to the idea of women having the parliamentary franchise, they already could vote local elections so it was just extending that right to them for national politics , but they couldn’t figure out how to do it and they were all worried about if they did extend the vote to women, would the women vote for another party, so it was about self-preservation: they wanted to stay in power and keep their constituencies and they felt threatened by the unknown. The suffrage movement began to fracture, creating a radical branch: the Women’s Social and Political Union(WSPU) also known as the Suffragettes. Ann: Between 1867 and 1913 there were no less than 40 attempts to pass bills and resolutions in the House of Commons in favour of women’s suffrage, they were all either defeated, given insufficient parliamentary time, ignored or blocked by the Government. The early suffrage bills had failed, because they were private member’s bills, these are bills proposed by individual MPs, rather than the Government and as such there were not guaranteed the necessary time to complete all of the parliamentary steps required for a bill to become law. This meant that women’s suffrage bills, even when they had a majority of votes in their favour failed to become law because of the lack of parliamentary time. Only a government-sponsored bill stood a realistic chance of becoming a law. And so the question the women had to anwer was : “How to convince the Government to sponsor a bill ? “ Ilona: For the Suffragists the answer was to continue to argue their case through patient lobbying, petitions, marches and other law-abiding campaigns, until they had convinced the government that the majority of the women wanted the vote and would use it responsibly. However for Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst’s WSPU aka The Suffragettes, the answer was a campaign of “DEEDS NOT WORDS”. A campaign that would be impossible for the government to ignore, a campaign that would not meekly ask the government for the vote, but demand it through political action. The deeds the suffragettes meant in their slogan initially included organising marches and demonstrations much as the suffragists were doing, campaigning in by-elections against government candidates and heckling ministers at public meetings; the latter certainly challenged Edwardian notions of femininity and respectability, but none of these tactics were in themselves criminal acts or even for that matter new. Ann: A key turning point came in 1908. In February 1907 and June 1908 large-scale suffragists and suffragettes demonstrations failed to convince the new Prime Minister Herbert Asquith that the majority of women wanted the vote. Emmeline Pethick Lawrence, a leading figure in the WSPU wrote that summer in “votes for women” : “We have touched the limit at a public demonstration, nothing but militant action is left to us now”. In 1909 Christabel Pankhurst (Mrs. Pankhurst's daughter) coordinated a new campaign that included breaking windows, setting fire to post boxes and even attempts to set fire to the country homes of government ministers. WSPU also continued to practice the older forms of militancy, such as public demonstrations. One such demonstration in November 1910 included an attempt to stall the lobby of the House of Commons. Frustrated by the impending failure of the conciliation bill, which would have given the vote to around 1 million wealthy, property-owning women. A 300 strong WSPU delegation reached Parliament, where they were subjected to a six hour long assault (both physical and indecent) by the police on what would become known as Black Friday. Ilona: In 1912 an assassination attempt was made on PM Ascuith in Dublin. By the 1913 The Suffragette WSPU was labelled a terrorist organization and up to a thousand suffragettes were imprisoned. For the next two years the WSPU caused extensive damage to properties across the United Kingdom: burning country houses, a school, more than 50 churches between 1913 and 1914 , the tea houses, bombs were planted and exploded on trains and in various buildings, including a failed destination in St. Paul’s Cathedral. Their calculation was that the government's desire to maintain law and order would outweigh its opposition to women's suffrage. First World War breaks out in 1914 and in some strange way it's actually an opportunity for Emmeline Pankhurst to stop the campaign, because it was kind of working itself into a dead end of violence. It’s important to highlight that suffrage wasn’t only an issue of women, more men wanted voting rights too. Ann: And after the war they couldn't have young man returning from the horrors of the First World War, who had served their countries the ultimate act of self-sacrifice and then not be given the right to vote. Up to 40% of men didn't have the right to vote in 1914 because they didn't own properties and they didn't meet the property qualifications. In 1916 the House of Commons decided to extend the vote to all men over the age of 21.The Suffragists saw this as an opportunity and they were very effective in ensuring that in those discussions at Westminster, women would receive the right to vote. Women over the age of 30, who owned property, were given the vote in 1918, enfranchising 8.4 million British women. And it took another 10 years before working class women could vote. Ilona: And it's important when we're looking back and remembering the history of the suffrage movement that we acknowledge that when social movements are using different forms of protest some of those really can be quite extreme and we can't really hide away from, perhaps, being a bit uncomfortable with some of the tactics that were used during the time, but at the same time recognizing the fact that in our world most things get done through violence and the Suffragettes were just following the rules established by men. And whether you agree with their methods or not, you can’t deny that brave women all over the world changed our democracy forever. The women got what they wanted, but it was only the beginning… We’ve come a long way since then in some ways, in others not so much. Surely, women now enjoy more political freedoms and as of today the UK has had 2 female prime-ministers. But the battle for equality is nowhere near the end and it’s our responsibility as women to honour those extraordinary females and keep on fighting(not as literally as the suffragettes did,obviously) until every woman is given the same rights as men.