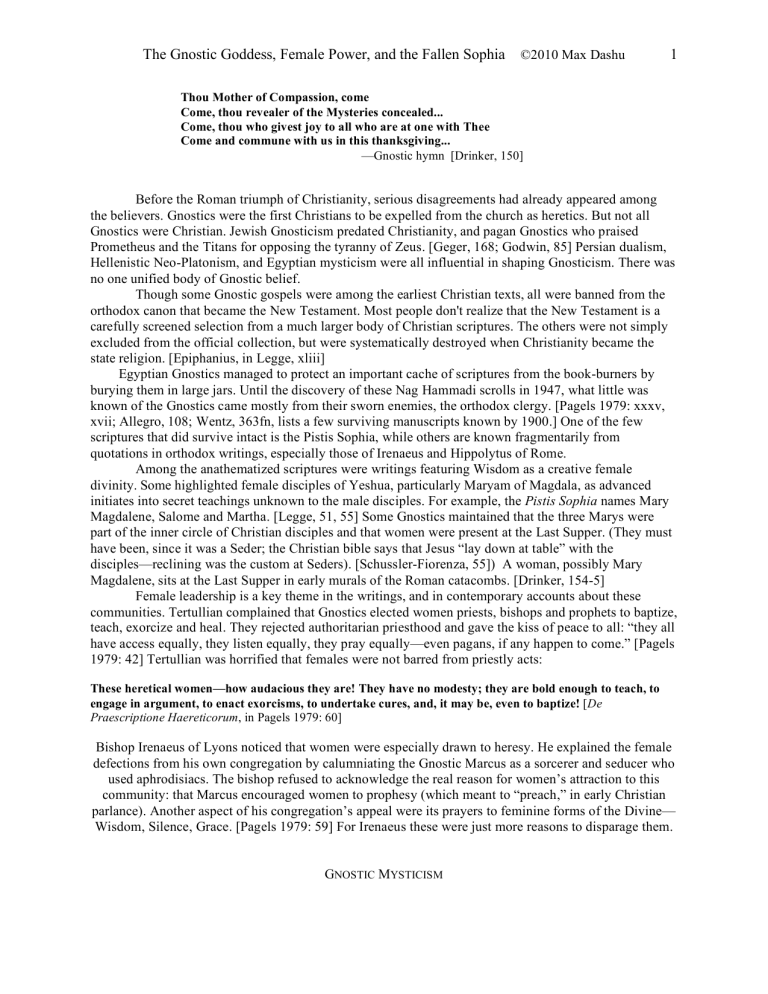

Gnostic Goddess, Sophia, and Female Power in Early Christianity

advertisement