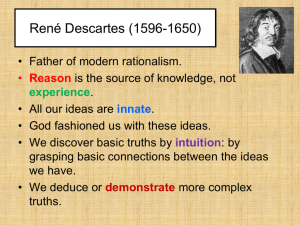

Revision:Aqa as philosophy epistemology notes We often make claims to knowledge – “I know that’s my stolen hat” When our knowledge is challenged we seek ways to justify it; appealing to further beliefs Sometimes we make mistakes – “I know that’s my stolen hat”, but we might be wrong, it might be an identical hat and circumstances might’ve led you to believe it was yours. How certain is knowledge then? Ordinary doubt is where we can be sceptical about what our senses tell us or about beliefs in single, specific situations. For example, “that’s John in the distance”. We might be sceptical of believing this if it is foggy or John looks very generic. But often we have no reason to distrust our senses; i.e. our eyes Descartes and doubt; first meditation Descartes notes that many things he believed he had knowledge of as a child turned out false He has a lot of false beliefs – he’s not sure how much true knowledge he has, so how can he go about finding out? He employs waves of doubt in order to withhold assent, doubting everything so that he can “start over”, finding, hopefully, foundational knowledge as the foundationalist he is Descartes’ first wave of doubt Descartes remarks that many times his senses have deceived him and questions whether they are deceiving him all of the time However – he says that because something has deceived us once, it would be silly to think they are deceiving us all the time. If he were to doubt that his hands were in front of him for this reason he would be no better than madmen. Descartes’ second wave of doubt Descartes notices that he has been convinced of things being real when asleep; for example that he was dressed in purple and gold when he was in fact wearing nothing in bed He questions; what if we were dreaming all of the time? How do we know what is certain if everything could be a dream This idea is rejected for 3 reasons: The existence of condition n requires n~, that is to say – dreaming requires a state of not dreaming to exist and so he cannot be dreaming all of the time Like painters model paintings on real life, dreams must be modelled on something real Whether dreaming or awake, 2 + 3 = 5. He cannot call this serious doubt if he cannot doubt logic. Austin notes that it is not true that we cannot distinguish between dreams and waking states, saying that dreaming that one is being presented to the pope is qualitatively different from the same in real life; for if it were not then every waking experience would be like a dream Curley challenges Austin – saying that at least some dreams are so vivid they are like real life. This is enough to hold up Descartes’ argument. William rejects this wave of doubt – as we can study dreaming from a waking state; there is asymmetry between dreaming and not dreaming. Descartes’ third wave of doubt Descartes imagines that there was a deceiving, all powerful God; an evil demon Though extremely contrived, this notion is possible A demon could deceive him of anything – even the logical truths of 2 + 3 = 5 (although this kills his argument, for if he says that logic is flawed then the Meditations are worthless) This is the cogito ergo sum arguement meaning "I think therefor I am" In order for a evil demon to decieve us, we must have a mind in which he can decieve, and if we have a mind then we must exist. Descartes and doubt; second meditation As Descartes is thinking, he realises this very notion – he is thinking What are the necessary qualities of existence then? To look at this from a transcendental argumentative perspective: existence To think we must exist – so Descartes summarises “I am, I think” (I think therefore I am/Cogito Ergo Sum) Descartes neglects the second premise; “everything that is thinking exists” because he regards it as ‘obvious’ as we construct premises like this in our mind on the basis of other premises and the conclusion. Descartes actually denies that the Cogito is an inference, remarking that it is an ‘analytical’ self evident truth, like those of mathematics. (yet he said he could doubt those earlier on… silly Descartes) Further developments in the second meditation Descartes tries to think what he is He detaches everything he thought he was before and see what remains What does remain is the fact that he thought So what is he? A thinking thing. Descartes makes a distinction between substance and essence – substance is something that can capably exist independently; for example the mind. The essence of the mind is thinking, or other modes of thinking Descartes and the wax (ooh!) Descartes pays attention to a piece of wax He remarks that it is hard, cold, emits a sound when tapped But when placed near the fire, these properties change Does the still wax remain? Yes, he argues So what is that we know of the wax if it is not what we perceive it to be The wax is known by the intellect – by our judgement He notes a second example – looking out of the window to see “people”, when all he really sees is coats and hats that may be operated by springs He realises at this point we must be careful with words – we don’t see people outside, we judge that there are people Descartes concludes that matter can be defined as “occupying geometrical space”. He says that there is only one material thing – the whole universe. There are therefore, two substances – mind and matter. He says that we know the mind better than the wax, as we can be certain of its properties, unlike the wax’s which change. However – this is odd as Margaret Dauler Wilson points out as he says we know the mind by listing its properties, despite saying that we cannot know the wax by listing its properties. Scepticism Global sceptics argue that we cannot know anything about the external world – as how can we be truly certain? A key question of Philosophy therefore, is how to defeat the sceptic. G.E.Moore says that the sceptic is wrong because he denies the common sense view of the world. He says that if we assert of ourselves; “there exists at present a living human body, which is my body”, this is undeniably true. Against the philosophers who argue that we cannot know this to be true; Moore retorts with the notion that if these philosophers really thought it open to question; for whom are they writing their Philosophy bokos? Furthermore; Moore says that when sceptics say; “we cannot know”, they are implying that there are other people who disagree with him, despite claiming that we cannot know that people exist. It’s all a bit contradictory. He also presents another argument. Raising one hand; says ‘this is one hand’, then the other, noting ‘this is another’. These are his two premises. His conclusion is that ‘two hands exist now’. Wittgenstein responds to Moore’s hands argument by saying that it does not make sense to say that he has two hands, as he had no real reason to doubt it. It makes as little sense to say this as it does to say “good morning” in the middle of a conversation with a friend. This does not mean Scepticism wins however, Wittgenstein says that philosophers who doubt that motorcars do not grow from trees have lost a real sense of doubt and are bordering on insanity. The fact that we have two hands is not something we learn, but just accept. Scepticism, according to Wittgenstein, is neither true nor false, but is lacking a proper sense of what counts as doubt and is therefore empty. Putnam on Scepticism Imagine there’s a planet called twin earth – where everything is identical to our earth. When Marcel on Earth refers to water, he refers to the chemical composition H2O When Twin Marcel on Twin Earth refers to water (which we shall call twater), he refers to the chemical composition XYZ. The appearance, taste, etc of water and twater are identical. This shows that meanings are outside the mind – they are affected by their physical environments. Let us suppose that you are a brain in a vat, being fed information. When you refer to tables and chairs, you’re not referring to real tables and chairs, but your images of them. Now imagine the brain in the vat says to himself: “I am a brain in a vat”. He is not referring to real vats, just as it can’t be referring to real tables, but images of vats that are being fed to him as he sits in the vat. So – when a brain in a vat says “I am a brain in a vat” – it is false. Generalising, then, if we are all brains in a vat, then we said “we are all brains in vats”, this would be false. So – it is false that we are all brains in a vat, we are not brains in a vat. Therefore scepticism is false. Indeed – this argument can be confusing. This type of argument is a reductio ad absurdum - a reduction to absurdity, as it starts of with the assumption of a proposition; p and reduces it to absurdity, the negation of p, disproving it. This argument, of course, would collapse if we proved that meanings are in the head. But for now this stands. Weaknesses G.E. Moore says that the sceptic is wrong because he denies the common sense view of the world. He says that if we assert of ourselves; “there exists at present a living human body, which is my body”, this is undeniably true. Many Philosophers argue we cannot know this, yet who are they writing their philosophy books for? They can't take their own scepticism seriously. Furthermore; Moore says that when sceptics say; “we cannot know”, they are implying that there are other people who disagree with him, despite claiming that we cannot know that people exist. It’s all a bit contradictory. He also presents another argument. Raising one hand; says ‘this is one hand’, then the other, noting ‘this is another’. These are his two premises. His conclusion is that ‘two hands exist now’. Wittgenstein responds to Moore’s hands argument by saying that it does not make sense to say that he has two hands, as he had no real reason to doubt it. It makes as little sense to say this as it does to say “good morning” in the middle of a conversation with a friend. This does not mean Scepticism wins however, Wittgenstein says that philosophers who doubt that motorcars do not grow from trees have lost a real sense of doubt and are bordering on insanity. The fact that we have two hands is not something we learn, but just accept. Scepticism, according to Wittgenstein, is neither true nor false, but is lacking a proper sense of what counts as doubt and is therefore empty. Putnam against scepticism: Imagine there’s a planet called twin earth – where everything is identical to our earth. When Marcel on Earth refers to water, he refers to the chemical composition H2O When Twin Marcel on Twin Earth refers to water (which we shall call twater), he refers to the chemical composition XYZ. The appearance, taste, etc of water and twater are identical. This shows that meanings are outside the mind – they are affected by their physical environments. Let us suppose that you are a brain in a vat, being fed information. When you refer to tables and chairs, you’re not referring to real tables and chairs, but your images of them. Now imagine the brain in the vat says to himself: “I am a brain in a vat”. He is not referring to real vats, just as it can’t be referring to real tables, but images of vats that are being fed to him as he sits in the vat. So – when a brain in a vat says “I am a brain in a vat” – it is false. Generalising, then, if we are all brains in a vat, then we said “we are all brains in vats”, this would be false. So – it is false that we are all brains in a vat; we are not brains in a vat. Therefore scepticism is false. Indeed – this argument can be confusing. This type of argument is a reductio ad absurdum - a reduction to absurdity, as it starts of with the assumption of a proposition; p and reduces it to absurdity, the negation of p, disproving it. This argument, of course, would collapse if we proved that meanings are in the head. But for now this stands. Strengths Stops any assumptions – used by Descartes to (supposedly) find indubitable knowledge The grounds for knowledge are challenged until we arrive at certainty (if any) It is impossible to eliminate subjectivity, as we cannot have a view from nowhere and thus scepticism is inescapable Rationalism Rationalism is the tendency to regard reason, as opposed to sense experience as the primary source of knowledge. It often argues that we have innate ideas of things; Plato in meno discusses Socrates asking a slave boy with no education mathematical questions. He answers them correctly. It is said that he must have known these truths a priori. Terms in Rationalism A priori knowledge – knowledge prior to experience, i.e. we can know 2 + 2 = 4 prior to experience. A posteriori knowledge – knowledge from (sense-)experience, i.e. we can know the rug is red after seeing it. Analytical propositions – propositions whose verity can be established through the meaning of the words alone, i.e. “this red book is this red book” or “all sisters are female”. One does not have to go out and examine the world to check if all sisters are female, it just is the case. Synthetic propositions – a proposition in which the predicate is not contained in the subject. “All crows are black” – the idea of black (predicate) is not an intrinsic part of crows (subject), whereas the predicate “female” cannot be detached from the subject of “sisters”. Necessary – something that is true in all possible worlds. For example, something cannot be blue all over and red all over at the same time. This assertion is necessary, it cannot be false. Contingent – A contingent truth is something that is true, but could conceivably not have been. For example “the rug is red” might be true, but it is quite possible it could be blue or green. It’s not necessary that it should be red. Kant says that 7 + 5 = 12 is synthetically a priori. Indeed this seems a contradiction, for a priori truths are usually attached to the idea of ‘necessity’. He notes that the predicates of 7 and 5 are not necessarily contained within the subject of 12. Kripke says that there are contingent a priori truths. Suppose someone sets up the metric system. He takes a stick – S and says that this stick is 1m long. How did he know it was 1m long? He knew it a priori because he did not have to investigate the world to determine it. However, he could’ve chosen any stick he liked, so 1m might’ve been otherwise. Kripke further argues that there are necessary a posteriori truths. We know gold has an atomic number 79, for if it did not have this atomic number, it would not be gold. But we did not know this a priori, we had to investigate the world; and gold, to determine this. This, therefore is an example of a necessary a posteriori truth. Weaknesses Provides us with nothing really useful about the external world Gives no knowledge of contingent truths Gives no empirical knowledge Gives no knowledge of natural sciences Presupposes the laws of logic are infallible (evil demon, anyone?) How could you have the concept of a triangle without ever seeing one? Locke on innate ideas – nations ignorant of the concept of God, fools who do not ‘know’ logical truths which are supposedly a priori Strengths Rational truths are eternally true They are necessary They can be known just by thinking about them – innate; Plato’s dialogue between Socrates and the slave boy. They are self justifying Has advantages over empiricism and a posteriori – sense deception Empiricism Contrasted with Rationalism It is the idea that the most important source of our knowledge is from sense-experience, not rational thought John Locke said that we are all born as tabula rasas (blank slates) on which we assimilate knowledge through sense experience. He denies that ideas, such as God are innate because there are entire nations who are ignorant of the idea of God or fools who cannot comprehend 2+3=5 Hume and causality David Hume takes to the limit the idea that we derive knowledge from experience in his theory of causality. We tend to believe as humans that an event – throwing a brick at a window (E1) will cause the window to break (E2) We think that it is necessary that the window breaks. Hume denies this; he says that we observe two things 1. One event happening before another, which he labels: “priority” 2. The collision of two objects, which he labels “contiguity” However, he notes that we have not observed the supposed part where E1 necessitates E2. He therefore denies that there is a necessary connection between “cause” and “effect”. There are simply events which happen in time. No matter how small the chances, atomic phenomena, for example, might cause the brick to cease existence before it reached the window. Indeed, something could always intervene. We humans think that there is a necessary link between cause and effect just as a matter of convenience. Just because something has always happened in the past does not mean that it will continue to happen this way. Just because the sun has always rose in the morning does not mean it will rise tomorrow morning. This is an attempt to explain our understanding of causal relations strictly within empiricist terms Empiricism vs A Priori knowledge So how do empiricists respond to supposed a priori truths, such as 2 + 2 = 4? AJ Ayer says that though it might be true that mathematical truths for instance are a priori, they tell us nothing of importance about the world AJ Ayer calls them “tautological” – i.e. this red book is this red book. A more radical view is propounded by J S Mill who says that mathematical truths are not necessary. He says that, like science, we have observed many instances of 2 + 6 equalling 8, but indeed we may have made a mistake all of these times. It could be according to J S Mill, that 2 + 6 indeed equals 9, we’ve just been miscounting all this time. Ayer rejects Mill’s argument, saying that even if he thought he had 5 pairs of something (10 items) and counted to find 9.. it would not be that 5 * 2 = 9, it would still remain that 5 * 2 = 10, he just miscounted. Weaknesses Concept formation not fully explained. I have a concept of red, and according to empiricism my concepts are kinds of copies of sensations. Yet my concept of red isn’t a particular shade of red. I have a concept of a chair; not any particular chair, but according to empiricism since I have derived this concept from experience it should really be a specific chair (one that I have experienced). I have a concept of justice, how did I form this concept? I can’t have through senseexperience; after all, justice doesn’t “smell” of flowers or “look” shiny. How does it explain innate ideas, i.e. Plato’s dialogue between Socrates and slave boy As Locke says – we only perceive the world indirectly. If so, how do we make the jump to experiencing the real world? If all I can be absolutely certain of is my experiences of sense data then I can’t be certain other minds exist! SOLIPSISM!! Conflict with a priori truths, empiricism has two general responses to them: 1. Yeah! But they don’t tell us anything of interest about the external world! 2. Ah but two apples plus three apples = 5 apples, we form concepts from experiences of seeing 2+3=5 Classical Foundationalism We often justify our beliefs by appealing to other beliefs However, this would mean there would be an endless infinite regress of justifying beliefs So foundationalists believe that there are beliefs which are self-supporting and self evident which are placed as the ‘foundations’ as our belief system In empiricism, the foundation is in the notion that one cannot be mistaken about how things seem to one now. H.H.Price: “When I see a tomato… I can doubt whether it is a tomato that I am seeing, and not a cleverly painted piece of wax… one thing however I cannot doubt: that there exists a red patch of a round and somewhat bulgy shape”. This “sense data” is known as ‘the given’. Assessment of Classical Foundationalism A J Ayer points out that one can make a mistake in one’s description of one’s experience – I might mistake “magenta” as “scarlet”. J L Austin replied to this – there might be any number of reasons why I might misdescribe something as “magenta” in such a way as to show that I actually made a mistake about which colour it was I was seeing, and not simply in the words I was using”. So there is nothing incorrigible about “the given”. However – if he watches for some time an animal in front of him, in good light, prod it, sniff it, listen to the noises and declare “that’s a pig” – this is incorrigible! There is nothing incorrigible about statements referring to sense-data, and there is nothing corrigible about statements referring to material bodies. Sellar’s myth of the given: We tend to utter “this is green” in front of green objects because we have authority One comes to gain this authority to say “this is green” in front of green objects by acquiring a general knowledge that in the presence of green objects the right thing to utter is “this is green” What comes to this is the idea that knowledge of particular matters of facts depend on general knowledge And how does one acquire this general knowledge? By being taught to utter “this is green” in front of green objects. So when one is an infant or child, one observed green objects but this observation did not constitute knowledge, as it lacked authority! Ergo, Foundationalism is mistaken! For ‘the given’ is meant to stand on its own feet, yet as we have seen in Sellar’s argument, it depends on authority! Coherentism The theory that beliefs are justified in terms of how well they cohere with other beliefs in the system Suppose an envelope arrives at my house, it’s empty. The only person silly enough to do this is Aunt Dotty, who lives in Exeter. But the letter is from Edinburgh and the writing is not hers. I’m not justified in believing the letter is from Aunt Dotty, because the beliefs don’t cohere. However, I recall my brother was going to take Dotty to Edinburgh and the writing is his! So she must’ve forgotten to put the letter in and got my brother to address it, so I am coherently justified in believing the letter is from her. It is a holistic theory; looks at the belief system as a whole. Assessing Coherentism Beliefs might internally cohere, but might all be wrong! This is illustrated by science fiction stories; everything coheres, but it’s far from the truth! Bradley rejected this – saying that Coherentism isn’t designed to test anything, but things we have a motivation to believe in. I have no reason to want to believe in science fiction, so even it internally coheres with other beliefs in its set, it doesn’t cohere with my entire system and I have no motivation to believe in it. Davidson formulated an argument against this criticism of Coherentism, indeed it is a little difficult to follow: Imagine a speaker of English, comes across speakers of “L”, a newly discovered, unknown language only they know. How will the English speaker ever understand the Ls? Davidson says he has to operate on the principle of charity, that is; he will have to assume that the beliefs of the speakers of L are by and large true. Otherwise, he won’t have enough common ground to compare beliefs and see which ones they disagree on But! Even if the interpreter must assume that he and the speakers of L share more or less the same beliefs, perhaps they are both completely wrong! How does he know his beliefs are not mistaken? Davidson says imagine there is an Omniscient Interpreter (God-like). This Interpreter will have to assume that he and the Ls share the same standards of truth. But – if this is the case, then it follows because his standards of truth cannot be mistaken, that the interpreter and the Ls cannot be wholly mistaken! Ergo, there is only one coherent set of beliefs Because we are giving up the search for absolute certainty, it gives us a more pragmatic and workable theory of knowledge It allows us to have knowledge of empirical truths, something rationalist Foundationalism could not achieve with its tautologies Justified true beliefs; the tripartite theory of knowledge This is the theory that knowledge is a “justified true belief”. That is, you must believe it, it must be true and you must be justified in your belief. Argument against: are the conditions necessary? Colin Radford argues it’s possible to know without believing. Suppose John learned in school that Elizabeth died in 1603. On a quiz show, he is asked when Elizabeth died. However, he has since forgotten he learned this, considering all his answers to be guesses. He would deny that he believes that Elizabeth died in 1603 despite giving the correct answer. Radford argues that he knows but doesn’t believe. This would argue that “belief” is not necessary to constitute knowledge D.M. Armstrong argues against this – saying that John consciously doesn’t believe he knows she died in 1603, but unconsciously does. Ergo, he believes p (that he believes) and ~p (that he does not believe); this is a contradiction, so it must be the case that belief is necessary. Argument against: are the conditions sufficient? Gettier argument: Imagine Smith & Jones are applying for a job at a bank. As they are sitting in the waiting room, they start chatting. Jones has far more qualifications and experience than Max and he is friends with the interviewer. Smith is aware Jones has 10 coins in his pocket Jones concludes that: the man who will get the job has 10 coins in his pocket However, Smith gets the job! Smith then discovers he has 10 coins in his pocket so; his proposition was true, he believed it and he was justified in believing it. Yet was this knowledge? No! It was an accident that he had the justified true belief. Another argument: Henry and William work in the same office. Henry believes William owns a ford, because he drives around in one and has given him lifts in one. Henry also has another colleague; Martha. Henry comes up with the random proposition: “either Henry owns a ford, or Martha is in Berlin”. Now suppose that Henry does not own a ford, and by strange co incidence Martha is in Berlin! The proposition is true; he believes it and it was justified. However, it was justified by the ‘ford’ element, yet the tripartite account still classifies it as knowledge! Criticism: “Justified true belief” – what the hell counts as justification? Looking it up in a book? Word of mouth? Or do I need to prove that Smith & Jones or Martha and Berlin exist first! Attempts to fix this theory; reliabilism: The Causal theory Suppose that Volcano, V, erupted many centuries ago and left lava all over the countryside. Suppose then that someone, A, removed all this lava. Even later, let us imagine, someone else, B, who does not know about the original eruption, put a lot of lava all over the countryside to make it look as if V had erupted. Nelson sees the lava and concludes that V erupted. Does he *know* this? Knowledge, then, is an appropriately caused true belief. This fixes the Gettier cases. There is a problem though – universal propositions. We might know that all tin openers are made by human beings, but this does not seem to be causally supported by the fact that all tin openers are made by human beings. It is unclear how my general belief about the mortality of all men can be caused by a belief that this man has died, and that one, however many men I believe to have died. Tracking the truth In the Gettier examples, if the propositions weren’t true, the people would still believe them. So, we must add this condition: if p were not true, then a would not believe p However, take Dancy’s argument: Hannah believes there is a police car outside because she hears sirens, and indeed there is. However, the sirens are coming from her son’s high fi, and if the high fi had been silent, she would not have believed it was there, so we must add this condition: If in changed circumstances, p were still true, a would still believe p. It can be concluded that justified true beliefs do not constitute knowledge, as this can be refuted by asking if the conditions are necessary or sufficient. Other reliabilist theories have attempted to fix this, introducing new conditions such as the causal theory and tracking the truth, but there are still problems with these. Common sense realism; naïve realism; direct realism The material world exists, and causes us to perceive it directly. Things are how we perceive them. Arguments against: Railway lines seem to get shorter in width as they go into the distance, yet we know they don’t! How can the world be as we perceive it then! Berkeley’s dialogue between Hylas and Philonous: clouds appear red, but on closer inspection, appear a different colour, and through a microscope, a different colour again! What is the true colour? Who knows, but we can conclude that these colours are merely “apparent” Hallucinations and illusions! Naïve realists argue in circles: We perceive things as they are So, we know what physical objects are like So, we perceive things as they are So, we know what physical objects are like Arguments in defence: Strawson’s realism: it is simply a part of common sense realism to allow for variation in the way things look. There mere fact that an object looks purple to me but green to you provides no reason to introduce “sense data”. However, this theory does not allow room to confront hallucinations. After all, when someone hallucinates there is a tree in front of him his experience is just as it would be were there a real tree there. Does this not show that even in the case of veridical perception a tree that the perceiver sees is a tree via a sense datum? John McDowell disputes this, arguing that our account of what is going on in a person who has an hallucination should be different from an account we give of what is going on in someone really seeing a tree. There is no difference ‘from the inside’ but is from an external perspective. Representative realism Our perceptions are merely representations of the real world; there is a veil of perception. We see sense data directly and the real world indirectly John Locke’s ideas can be summarised as follows: Those without sense organs never have experiences of sense data (ideas). From this, Locke infers that sense organs do not produce the ideas, these ideas must be caused by objects outside. I cannot smell a rose when I want, it must be called by something external. Therefore the material world must exist. However, Locke talks about sense organs, how do we know these aren’t just ideas in themselves? Also, the smell of roses could be produced by an idea-creating God, and not material objects. Strengths: Deception can be explained, unlike in Naïve realism Explains secondary qualities (subjectivity of perceivers) Agrees with the sciences; that only light waves exist and not ‘colours’, which are simply concepts. Weaknesses: How do we know when we’re being deceived if we are not perceiving the world directly? It assumes the existence of a real world (see Locke’s argument & criticism above) It is unclear what properties sense data are supposed to have, it is supposed to be nonphysical. Yet if I see a green cube in front of me, could it be said I am seeing a non physical green cuboid? This seems silly! Ridiculous! Matter is an empty concept since we never experience it Idealism There is no material world, only minds and their ideas! :D To be is to be perceived; esse est percipi Strengths: Material world can’t exist because we never experience matter, so the concept of it is empty! Weaknesses: Solipsism – all that exist are minds and ideas, so maybe all the other minds are simply ideas in your mind! Agh! Has to explain the problem that, the idea of a tree in my mind is no different then an idea of a conscious phone box I have imagined. Berkeley explains this by saying that ideas of the imagination are not stable and voluntary. That is, I have no choice of what to see when I open my eyes and what I ‘see’ remains consistent, unlike in the imagination. Unperceived objects – does a chair stop existing when no one perceives it? Berkeley said they continue to exist, because they are ideas in God’s mind: There was a young man who said ‘God Must think it exceedingly odd If he finds that this tree Continues to be When there’s no one about in the quad Reply: Dear Sir: Your astonishment’s odd; I am always about in the quad. And that’s why the tree Will continue to be, Since observed by yours faithfully, God. This does however depend upon the existence of God! However, Berkeley seems to be bordering on phenomenalism at one point (odd :s ): “The table I write on, I say, exists, that is, I see and feel it; and if I were out of my study I should say it existed, meaning thereby that if I was in my study I might perceive it” (to be is to be perceivable) Phenomenalism Several types. Mill’s phenomenalism talks of “permanent possibilities of sensation” AJ Ayer’s linguistic phenomenalism: “every empirical statement about a physical object is reducible to a statement, or a set of statements which refer exclusively to sense-data”. Strengths: Closes the gap between experience and the real world, as it is anti-realist Doesn’t rely on God Weaknesses: Isn’t the same miracle that Berkeley needed God to explain required for why objects exist unperceived and are consistent in existence? Surely it’s not enough just to declare them ‘permanent possibilities of sensation’. Phenomenalists usually respond to this by appealing to regularities in past experience This can still be refuted. Trees don’t reappear when I walk into the forest because it has reappeared in the past, rather it has reappeared in the past because it was there all along. It exists, independently. The realist says the phenomenalist just gets things the wrong way around. All spatial language is gained from the public world, which is then rejected! Yet use of words like ‘on’ continues! Hypocrisy! Linguistic phenomenalism makes our lives hell by forcing us to translate into phenomenalese; it would be impossible to talk fully in terms of sense data! Surely if things are ‘permanent possibilities of sensation’ this is hinting at the existence of a material world Sense data being indeterminate: if I was not paying attention to what colour something was, I am not sure what colour it was; does this mean it has no colour or no fixed colour