Philippine Legal Case Summaries: Esguerra & Mendoza

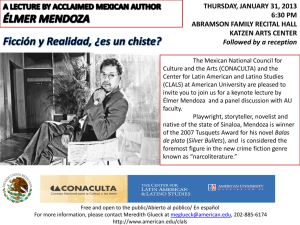

advertisement

(y) Feliciano Esguerra, et. al., v. Virginia Trinidad, et. al., G.R. No. 169890, March 12, 2007; Sales (zz) Mendoza v. Paule, 579 SCRA 341 (2009); Agency (ss) Cornelio M. Isaguirre v. Felicitas De Lara, GR No. 138053, May 31, 2000; Credit Transaction FELICIANO ESGUERRA, et al. v. VIRGINIA TRINIDAD, et al. 518 SCRA 186 (2007) What really defines a piece of ground is not the area, calculated with more or less certainty, mentioned in its description, but the boundaries therein laid down, as enclosing the land and indicating its limits. Felipe Esguerra and Praxedes de Vera (Esguerra spouses) owned several parcels of land half of which they sold to their grandchildren Feliciano, Canuto, Justa, Angel, Fidela, Clara and Pedro, all surnamed Esguerra. The spouses sold half the remaining land were sold their other grandchildren, the brothers Eulalio and Julian Trinidad.. Subsequentlly, the Esguerra spouses executed the necessary Deeds of Sale before a notary public. They also executed a deed of partitioning of the lots , all were about 5,000 square meteres each. Eulalio Trinidad (Trinidad) later sold his share of the land to his daughters. During a cadastral survey conducted in the late 1960s, it was discovered that the 5,000-square meter portion of Esguerra‘s parcel of land sold to Trinidad actually measured 6,268 square meters. Feliciano Esguerra (Feliciano), who inhabits the lot bordering Trinidad, subsequently filed a motion for nullification of sale between the Esguerra spouses and Trinidad on the ground that they were procured through fraud or misrepresentation. Feliciano contended that the stipulations in the deed of sale was that Trinidad was sold a 5,000 square meter lot. The boundaries stipulated in the contract of sale which extend the lot‘s area Both cases were consolidated and tried before the RTC which, after trial, dismissed the cases. On appeal, the appellate court also dismissed the cases; and subsequently, the motion for reconsideration was also denied. ISSUES: Whether or not the Appellate Court erred in holding that the description and boundaries of the lot override the stated area of the lot in the deed of sale HELD: Where both the area and the boundaries of the immovable are declared, the area covered within the boundaries of the immovable prevails over the stated area. In cases of conflict between areas and boundaries, it is the latter which should prevail. What really defines a piece of ground is not the area, calculated with more or less certainty, mentioned in its description, but the boundaries therein laid down, as enclosing the land and indicating its limits. In a contract of sale of land in a mass, it is well established that the specific boundaries stated in the contract must control over any statement with respect to the area contained within its boundaries. It is not of vital consequence that a deed or contract of sale of land should disclose the area with mathematical accuracy. It is sufficient if its extent is objectively indicated with sufficient precision to enable one to identify it. An error as to the superficial area is immaterial. Thus, the obligation of the vendor is to deliver everything within the boundaries, inasmuch as it is the entirety thereof that distinguishes the determinate object. Under the Torrens System, an OCT enjoys a presumption of validity, which correlatively carries a strong presumption that the provisions of the law governing the registration of land which led to its issuance have been duly followed. Fraud being a serious charge, it must be supported by clear and convincing proof. Petitioners failed to discharge the burden of proof, however. The same rule shall be applied when two or more immovables are sold for a single price; but if, besides mentioning the boundaries, which is indispensable in every conveyance of real estate, its area or number should be designated in the contract, the vendor shall be bound to deliver all that is included within said boundaries, even when it exceeds the area or number specified in the contract; and, should he not be able to do so, he shall suffer a reduction in the price, in proportion to what is lacking in the area or number, unless the contract is rescinded because the vendee does not accede to the failure to deliver what has been stipulated. In fine, under Article 1542, what is controlling is the entire land included within the boundaries, regardless of whether the real area should be greater or smaller than that recited in the deed. This is particularly true since the area of the land in OCT No. 0-6498 was described in the deed as “humigit kumulang,” that is, more or less. A caveat is in order, however. The use of “more or less” or similar words in designating quantity covers only a reasonable excess or deficiency. A vendee of land sold in gross or with the description “more or less” with reference to its area does not thereby ipso facto take all risk of quantity in the land MENDOZA V PAULE G.R. No. 175885 February 13, 2009 By: Jeah Dominguez FACTS: Engineer Paule is the proprietor of E.M. Paule Construction and Trading (EMPCT). PAULE executed an SPA authorizing Mendoza to participate in the pre-qualification and bidding of a National Irrigation Administration (NIA) project, the Casicnan Multi-Purpose Irrigation and Power Plant (CMIPPL). Mendoza was given the power to bid and secure bonds with the NIA as well as receive and collect payments. EMPCT, through Mendoza, was awarded the project. When Cruz learned the Mendoza was in need of heavy equipment for use in the NIA project, he met up with him to discuss an agreement for such project. The product of their agreement was two job orders for dump trucks on December of 1999. On April 2000, Paule revoked the SPA of Mendoza prompting NIA to refuse payment on her billings. CRUZ, therefore, could not be paid for the rent of the equipment. Upon advice of MENDOZA, CRUZ addressed his demands for payment of lease rentals directly to NIA but the latter refused to acknowledge the same and informed CRUZ that it would be remitting payment only to EMPCT as the winning contractor for the project. Cruz then sued Paule (EMPTC) and NIA. Paule proceeds against Mendoza. MENDOZA alleged in her cross-claim that because of PAULEs whimsical revocation of the SPA, she was barred from collecting payments from NIA, thus resulting in her inability to fund her checks which she had issued to suppliers of materials, equipment and labor for the project. She claimed that estafa and B.P. Blg. 22 cases were filed against her. RECAP! Cruz: Mendoza/Paule/EMPTC/NIA needs to pay because Mendoza was the agent of EMPTC and she incurred liabilities pursuant to the NIA project! Paule: I shouldn’t pay nor forward the money I have from NIA because Mendoza acted outside the scope of her authority! Mendoza: I acted within the scope of my authority and am now facing charges with liabilities I incurred which weren’t even mine to begin with since I was just an agent! Paule/EMPTC/NIA should pay me! Lower Court said Paule is liable as Mendoza acted as agent while CA reversed and said that Mendoza was in excess so Paule was not liable. ISSUES: 1. On Paule’s and Mendoza’s side: Whether or not Mendoza, as agent, could claim from Paule/EMPTC for debts she incurred from Cruz? 2. On Cruz’s side: Whether or not Paule/EMPTC is liable as Mendoza was an agent that acted within the scope of her authority? HELD: BIGLA NALANG MAY PARTNERSHIP WHOA. “Records show that PAULE (or, more appropriately, EMPCT) and MENDOZA had entered into a PARTNERSHIP in regard to the NIA project. PAULEs contribution thereto is his contractors license and expertise, while MENDOZA would provide and secure the needed funds for labor, materials and services; deal with the suppliers and subcontractors; and in general and together with PAULE, oversee the effective implementation of the project. For this, PAULE would receive as his share three per cent (3%) of the project cost while the rest of the profits shall go to MENDOZA. PAULE admits to this arrangement in all his pleadings.” 1. YES. Although the SPA limited Mendoza only to bid on behalf of EMPTC with regard the project, MENDOZAs actions were in accord with what she and PAULE originally agreed upon, as to division of labor and delineation of functions within their partnership. Under the Civil Code, every partner is an agent of the partnership for the purpose of its business; each one may separately execute all acts of administration, unless a specification of their respective duties has been agreed upon, or else it is stipulated that any one of them shall not act without the consent of all the others. At any rate, PAULE does not have any valid cause for opposition because his only role in the partnership is to provide his contractors license and expertise, while the sourcing of funds, materials, labor and equipment has been relegated to MENDOZA. 2. YES. Given the present factual milieu, CRUZ has a cause of action against PAULE and MENDOZA. Thus, the Court of Appeals erred in dismissing CRUZs complaint on a finding of exceeded agency. There was no valid reason for PAULE to revoke MENDOZAs SPAs. Since MENDOZA took care of the funding and sourcing of labor, materials and equipment for the project, it is only logical that she controls the finances, which means that the SPAs issued to her were necessary for the proper performance of her role in the partnership, and to discharge the obligations she had already contracted prior to revocation. Without the SPAs, she could not collect from NIA, because as far as it is concerned, EMPCT and not the PAULE-MENDOZA partnership is the entity it had contracted with. Without these payments from NIA, there would be no source of funds to complete the project and to pay off obligations incurred. As MENDOZA correctly argues, an agency cannot be revoked if a bilateral contract depends upon it, or if it is the means of fulfilling an obligation already contracted, or if a partner is appointed manager of a partnership in the contract of partnership and his removal from the management is unjustifiable. Moreover, PAULE should be made civilly liable for abandoning the partnership, leaving MENDOZA to fend for her own, and for unduly revoking her authority to collect payments from NIA, payments which were necessary for the settlement of obligations contracted for and already owing to laborers and suppliers of materials and equipment like CRUZ, not to mention the agreed profits to be derived from the venture that are owing to MENDOZA by reason of their partnership agreement. Isaguirre vs. De Lara Cornelio M. Isaguirre vs. Felicitas De Lara G.R. No. 138053, May 31, 2000 Gonzaga-Reyes, J. Doctrine: As a general rule, the mortgagor retains possession of the mortgaged property since a mortgage is merely a lien and title to the property does not pass to the mortgagee. However, even though a mortgagee does not have possession of the property, there is no impairment of his security since the mortgage directly and immediately subjects the property upon which it is imposed, whoever the possessor may be, to the fulfillment of the obligation for whose security it was constituted. If the debtor is unable to pay his debt, the mortgage creditor may institute an action to foreclose the mortgage, whether judicially or extra judicially, whereby the mortgaged property will then be sold at a public auction and the proceeds there from given to the creditor to the extent necessary to discharge the mortgage loan. Facts: Alejandro de Lara was the original applicant-claimant for a Miscellaneous Sales Application over a parcel of land identified as portion of Lot 502, Guianga Cadastre, filed with the Bureau of Lands with an area of 2,342 square meters. Upon his death, his wife – respondent Felicitas de Lara, as claimant, succeeded Alejandro de Lara. The Undersecretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources amended the sales application to cover only 1,600 square meters. By virtue of a decision rendered by the Secretary of Agriculture and Natural Resources, a subdivision survey was made and the area was further reduced to 1,000 square meters. On this lot stands a two-story residential-commercial apartment declared for taxation purposes in the name of respondent’s sons – Apolonio and Rodolfo, both surnamed de Lara. Respondent obtained several loans from the Philippine National Bank. When she encountered financial difficulties, respondent approached petitioner Cornelio M. Isaguirre, who was married to her niece, for assistance. A document denominated as “Deed of Sale and Special Cession of Rights and Interests” was executed by respondent and petitioner, whereby the former sold a 250 square meter portion of Lot No. 502, together with the two-story commercial and residential structure standing thereon, in favor of petitioner, for and in consideration of the sum of P5,000. Apolonio and Rodolfo de Lara filed a complaint against petitioner for recovery of ownership and possession of the two-story building. However, the case was dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. Petitioner filed a sales application over the subject property on the basis of the deed of sale. His application was approved, resulting in the issuance of Original Certificate of Title, in the name of petitioner. Meanwhile, the sales application of respondent over the entire 1,000 square meters of subject property (including the 250 square meter portion claimed by petitioner) was also given due course, resulting in the issuance of Original Certificate of Title, in the name of respondent. Due to the overlapping of titles, petitioner filed an action for quieting of title and damages with the RTC of Davao City against respondent. After trial on the merits, the trial court rendered judgment, in favor of petitioner, declaring him to be the lawful owner of the disputed property. However, the Court of Appeals reversed the trial court’s decision, holding that the transaction entered into by the parties, as evidenced by their contract, was an equitable mortgage, not a sale. The appellate court’s decision was based on the inadequacy of the consideration agreed upon by the parties, on its finding that the payment of a large portion of the “purchase price” was made after the execution of the deed of sale in several installments of minimal amounts; and finally, on the fact that petitioner did not take steps to confirm his rights or to obtain title over the property for several years after the execution of the deed of sale. As a consequence of its decision, the appellate court also declared Original Certificate issued in favor of petitioner to be null and void. This Court affirmed the decision of the Court of Appeals, we denied petitioner’s motion for reconsideration. Respondent filed a motion for execution with the trial court, praying for the immediate delivery of possession of the subject property, which motion was granted. Respondent moved for a writ of possession. Petitioner opposed the motion, asserting that he had the right of retention over the property until payment of the loan and the value of the improvements he had introduced on the property. The trial court granted respondent’s motion for writ of possession. The trial court denied petitioner’s motion for reconsideration. Consequently, a writ of possession, together with the Sheriff’s Notice to Vacate, was served upon petitioner. Issue: Whether or not the mortgagee in an equitable mortgage has the right to retain possession of the property pending actual payment to him of the amount of indebtedness by the mortgagor. Held: A mortgage is a contract entered into in order to secure the fulfillment of a principal obligation. Recording the document, in which it appears with the proper Registry of Property, although, even if it is not recorded, the mortgage is nevertheless binding between the parties, constitutes it. Thus, the only right granted by law in favor of the mortgagee is to demand the execution and the recording of the document in which the mortgage is formalized. As a general rule, the mortgagor retains possession of the mortgaged property since a mortgage is merely a lien and title to the property does not pass to the mortgagee. However, even though a mortgagee does not have possession of the property, there is no impairment of his security since the mortgage directly and immediately subjects the property upon which it is imposed, whoever the possessor may be, to the fulfillment of the obligation for whose security it was constituted. If the debtor is unable to pay his debt, the mortgage creditor may institute an action to foreclose the mortgage, whether judicially or extrajudicially, whereby the mortgaged property will then be sold at a public auction and the proceeds there from given to the creditor to the extent necessary to discharge the mortgage loan. Apparently, petitioner’s contention that “to require him to deliver possession of the Property to respondent prior to the full payment of the latter’s mortgage loan would be equivalent to the cancellation of the mortgage is without basis. Regardless of its possessor, the mortgaged property may still be sold, with the prescribed formalities, in the event of the debtor’s default in the payment of his loan obligation. A simple mortgage does not give the mortgagee a right to the possession of the property unless the mortgage should contain some special provision to that effect. Regrettably for petitioner, he has not presented any evidence, other than his own gratuitous statements, to prove that the real intention of the parties was to allow him to enjoy possession of the mortgaged property until full payment of the loan. The trial court correctly issued the writ of possession in favor of respondent. Such writ was but a necessary consequence of affirming the validity of the original certificate of title in the name of respondent Felicitas de Lara, while at the same time nullifying the original certificate of title in the name of petitioner Cornelio Isaguirre. Possession is an essential attribute of ownership; thus, it would be redundant for respondent to go back to court simply to establish her right to possess subject property. Caveat: Anyone who claims this digest as his own without proper authority shall be held liable under the law of Karma.