ACCEPTANCE AND COMMITMENT THERAPY

FOR THE TREATMENT OF PERFECTIONISM

A Dissertation

Presented to the Faculty of the

School of Human Services Professions

Widener University

In Partial Fulfillment

Of the Requirements for the Degree

Doctor of Psychology

By

Steven Bisgaier

Institute for Graduate Clinical Psychology

January 2018

ProQuest Number: 10816869

All rights reserved

INFORMATION TO ALL USERS

The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted.

In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.

ProQuest 10816869

All rights reserved.

This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code

Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.

ProQuest LLC.

789 East Eisenhower Parkway

P.O. Box 1346

Ann Arbor, MI 48106 - 1346

Copyright by

Steven Bisgaier

2018

Abstract

Perfectionism is prevalent in a wide range of psychiatric disorders (e.g., depression, anxiety, disordered eating, OCD, PTSD) and physical health problems (e.g., chronic pain, migraine, asthma, fatigue). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) protocols have been developed to treat perfectionism, yet no studies have evaluated its effectiveness. This pilot study examined the effectiveness of ACT in treating perfectionism in five undergraduate students with perfectionism as a primary feature of either generalized anxiety disorder or depression. The study used a one-group pretest-posttest design. Individual treatment lasted between seven and twelve sessions and was administered flexibly (i.e., non-manualized). Acknowledging the small sample size, significant improvement with large effect sizes were found on measures of depression ( p =

.012, d = 1.98), general anxiety ( p

= .011, d = 2.01), social anxiety ( p

= .009, d = 2.11), general distress ( p

= .008, d = 2.17), frequency and awareness of thoughts related to perfectionism ( p

=

.003, d = 3.00), psychological flexibility ( p

= .017, d = 1.76), cognitive fusion ( p

= .013, d =

1.89), and commitment to values-consistent action ( p

= .050, d = 1.24). These findings provide preliminary support for the effectiveness of ACT as a treatment for perfectionism and the need for a future randomized control trial. The study suggests three primary mechanisms of change: 1) reduction in experiential avoidance; 2) increase in cognitive defusion; and 3) clarification of personal values. The study adds to existing evidence indicating that direct and explicit treatment of perfectionism can provide remittance of symptoms of other mental health issues.

Key words: perfectionism, acceptance and commitment therapy, ACT, case study, college students

Table of Contents

Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... iv

List of Tables ................................................................................................................................ vii

List of Appendices ....................................................................................................................... viii

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Perfectionism .................................. 1

The Clinical Importance of Perfectionism .................................................................................. 2

Measures and Definitions of Perfectionism ................................................................................ 3

Perfectionism as a Maladaptive Construct .................................................................................. 4

Treatment for Perfectionism ....................................................................................................... 6

Overview of ACT ....................................................................................................................... 7

ACT for the Treatment of Perfectionism .................................................................................... 8

Method ............................................................................................................................................ 9

Participants .................................................................................................................................. 9

Therapist ................................................................................................................................... 10

Design ....................................................................................................................................... 10

Measures ................................................................................................................................... 10

Treatment Overview and Core Process Targets........................................................................ 12

ACT introduction and creative hopelessness ........................................................................ 13

Cognitive defusion ................................................................................................................ 15

Experiential avoidance and acceptance ................................................................................ 17

Values-consistent action ....................................................................................................... 18

Present-moment awareness and exposure ............................................................................. 20

Self-as-context ...................................................................................................................... 22

Self-compassion .................................................................................................................... 22

Results and Case Descriptions ...................................................................................................... 24

The Case of Daniel.................................................................................................................... 26

The Case of Sara ....................................................................................................................... 29

The Case of Chloe ..................................................................................................................... 33

The Case of Margaret................................................................................................................ 36

The Case of Tamara .................................................................................................................. 40

General Discussion ....................................................................................................................... 42

Limitations ................................................................................................................................ 46

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................ 46

References ..................................................................................................................................... 48

List of Tables

Table 1: Pre and Post Data for Psychological Flexibility and Perfectionism Measures … ... 25

Table 2: Pre and Post Data for CCAPS-34 ………………………………………………… 25

Table 3: Pre and Post Data for Group Means ……………………………………………… 25

List of Appendices

Appendix A: Acceptance and Action QuestionnaireII…………………………………… 62

Appendix B: Short Form of the Revised Almost Perfect Scale…………………………… 63

Appendix C: Perfectionism Cognitions Inventory………………………………………… 64

Appendix D: Valuing Questionnaire……………………………………………………….

65

Appendix E: Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire……………………………………………..

66

Appendix F: Study Recruitment Flyer……………………………………………………..

67

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for the Treatment of Perfectionism

Broadly, perfectionism is commonly defined as the propensity to set and demand excessively high standards for oneself, accompanied by excessive self-criticism, regardless of performance (Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990; Stoeber & Otto, 2006). It is a

1 transdiagnostic process that is predominant in numerous clinical disorders and has been associated with a wide range of physical health problems and social dysfunction. Various psychotherapeutic interventions, including psychodynamic and cognitive behavioral therapies, have been developed and utilized in the treatment of perfectionism with mixed results.

Recently, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) has been identified as a a potentially applicable intervention for perfectionism. Protocols have been developed for utilizing ACT to treat perfectionism as a primary problem (Crosby, Armstrong, Nafziger, &

Twohig, 2013), or when it manifests as an underlying feature of other psychological problems, including eating disorders (Sandoz, Wilson, & DuFrene, 2011) and body image dissatisfaction

(Pearson, Heffner, & Follette, 2010). However, studies do not exist that were designed to evaluate the effectiveness of ACT interventions for the treatment of perfectionism.

This dissertation evaluated the use of ACT in the psychotherapeutic treatment of five students who presented at a university counseling center with perfectionism as a primary problem. Students were evaluated at the start and end of treatment on measures designed to determine the efficacy of ACT in reducing symptoms of perfectionism and other mental health conditions and in improving psychological flexibility. The interventions were catalogued to explore how patients experienced and responded to ACT as a treatment for their condition. I predicted that perfectionism, perfectionistic thoughts, and symptoms of various mental health conditions would be significantly reduced, and that psychological flexibility would be

significantly increased.

The Clinical Importance of Perfectionism

While the American Psychiatric Association (APA) has not yet identified perfectionism as an independent diagnosis, perfectionism is recognized as a possible feature of generalized

2 anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, hoarding disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder (APA, 2013).

Perfectionism has been described as a transdiagnostic process, appearing as “a major factor that can explain the maintenance of numerous disorders that an ind ividual may experience” (Egan,

Wade, & Shafran, 2012, p. 280). Indeed, an abundance of research has revealed it to be prevalent in a wide range of clinical disorders (Egan, Wade, & Shafran, 2011, 2012), including depression

(Enns, Cox, & Borger, 2001; Hewitt & Flett, 1991a; Huprich, Porcerelli, Keaschuk, Binienda, &

Engle, 2008), anxiety (Frost & DiBartolo, 2002; Gentes & Ruscio, 2014; Hayward & Arthur,

1998), social anxiety (Alden, Ryder, & Mellings, 2002; Antony, Purdon, Huta, & Swinson,

1998; Saboonchi, Lundh, & Öst, 1999), eating disorders (Bardone-Cone et al., 2007; Sassaroli et al., 2008), obsessive-compulsive disorder (Frost & Steketee, 1997; Frost, Novara, & Rhéaume,

2002), and posttraumatic stress disorder (Egan, Hattaway, & Kane, 2014). Additionally, perfectionism has been linked to a variety of physical health problems, including asthma, chronic pain, fatigue, headaches, migraines, and the management of chronic illnesses (Molnar, Sirois, &

Methot-Jones, 2016). Finally, perfectionism has been seen to contribute to various other forms of dysfunction, ranging from suicidality (Hewitt, Flett, Sherry, & Caelian, 2006; O’Connor, 2007) to relationship problems (Habke, Hewitt, & Flett, 1999; Habke & Flynn, 2002; Matte &

Lafontaine, 2012).

Measures and Definitions of Perfectionism

The three most prevalent measures of perfectionism are the Frost Multidimensional

Perfectionism Scale (F-MPS; Frost, Marten, Lahart, & Rosenblate, 1990), the Hewitt and Flett

Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (HF-MPS; Hewitt & Flett, 1991b), and the Revised

3

Almost Perfect Scale (APS-R; Slaney, Rice, Mobley, Trippi, & Ashby, 2001). These scales all embrace the current view of perfectionism as multidimensional construct. The F-MPS consists of

6 subscales: personal standards (PS; setting high standards for performance); doubts about actions (DA; doubting the quality of performance); concern over mistakes (CM; tendency to be critical of one’s mistakes ); organization (O; placing an emphasis on organization); parental expectations (PE ; placing value on parent’s expectations ); and parental criticism (PC; placing value on parent’s criticism ). The HF-MPS consists of 3 subscales: self-oriented perfectionism

(SOP; setting high standards , stringently evaluating one’s behavior, striving to attain perfection and avoid failure); other-oriented perfectionism (OOP; setting high standards for others, stringently evaluating other’s behavior ); and socially prescribed perfectionism (SPP; believing that others have high standards for you and are stringently evaluating you). The APS-R consists of 3 subscales: high standards (HS; self-performance expectations and standards); order (OR; self-preferences for order and organization); and discrepancy (D; perceived difference between the standards one has for oneself and one’s actual performance). Recently, as part of their

Comprehensive Model of Perfectionistic Behavior (CMPB), Hewitt and colleagues (2017) have expanded their conceptualization of perfectionism, adding interpersonal components (namely, perfectionistic self-promotion, nondisplay of imperfections, and nondisclosure of imperfections) and intrapersonal or self-relational components (automatic ruminative self-statements regarding the attainment of perfection) to the 3 subscales of the HF-MPS.

Each of these measures is highly regarded (Flett & Hewitt, 2015); however, factor analytic studies have consistently winnowed the many subscales identified above down to two

4 central components, commonly referred to as perfectionistic strivings and perfectionistic concerns

(Bieling, Israeli, & Antony, 2004; Cox, Enns, & Clara, 2002; Frost, Heimberg, Holt,

Mattia, & Neubauer, 1993). “ Perfectionistic Strivings ” denotes the perfectionist’s tendency to set excessively high personal standards and to expect perfection of one’s self. These characteristics are captured by the PS subscale of the F-MPS, the SOP subscale of the HF-MPS, and the HS subscale of the APS-R. “ Perfectionistic Concerns ” denotes the perfectionist’s tendency to be highly self-critical regardless of performance and to be overly concerned with the evaluations of others. These characteristics are captured by the DA, CM, PE, and PC subscales of the F-MPS, the SPP subscale of the HF-MPS, and the D subscale of the APS-R. In consideration of these two central constructs of perfectionism, the following working definition of perfectionism was utilized in this study: Perfectionism is the propensity to set and demand unachievably high standards for oneself, accompanied by excessive self-criticism, regardless of performance.

Perfectionism as a Maladaptive Construct

Originally, theorists viewed perfectionism as purely maladaptive and unidimensional.

Early researchers saw perfectionists as people who set unattainably high standards as a consequence of a fear of failure and low self-esteem (Beck, 1976; Horney, 1950; Missildine,

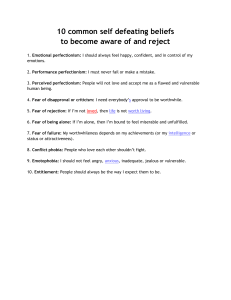

1963). Accordingly, one of the earliest assessments of perfectionism, The Burns Perfectionism

Scale (BPS; Burns, 1980), featured a unidimensional, maladaptive view of perfectionism, with ten questions designed to capture a person’s perfectionism through the lens of various self defeating attitudes (e.g., “If I don’t set the highest standards for myself, I am likely to end up a second-rate person ” ).

This view of perfectionism as exclusively maladaptive was soon contested. In an early, influential work on perfectionism, Don Hamachek (1978) differentiated between “neurotic

5 perfectionists” and “normal perfectionists.” He defined “ normal perfectionism ” as a desirable trait, characterized by a relaxed and careful attitude, increased potential for success, enhanced self-esteem, and a personal sense of satisfaction (Hamachek, 1978). Contrarily, he defined

“neurotic perfectionism” as maladaptive, characterized by a person setting performance standards so unattainable that even his best efforts leave him unsatisfied (Hamachek, 1978). In the years since, other theorists have argued in favor of a positive conceptualization of perfectionism (see Stoeber & Otto, 2006 for a review). Components of the various multidimensional perfectionism scales have been organized by researchers into measures of positive or adaptive perfectionism (e.g., PS and O from the F-MPS, SOP and OOP from the HF-

MPS, and HS and OR from the APS-R), and in some cases these components of perfectionism have been shown to associate with adaptive traits, such as higher levels of positive affect (Frost et al., 1993), conscientiousness and endurance (Stumpf & Parker, 2000), and satisfaction with life (Chang, Watkins, & Banks, 2004).

The counterarguments to the identification of perfectionism as a positive trait are persuasive. The evidence that links perfectionism to psychological and physical health dysfunction are well documented; outweighing evidence to the contrary. Additionally, researchers have argued that what others call adaptive perfectionism is more accurately a separate and distinct personality trait better described as “excessive conscientiousness” or

“ striving for excellence ” (Greenspon, 2000; Hewitt, Flett, & Mikail, 2017).

Ultimately, the apparent disagreement may come down to a case of semantics and practicality. There is a reason why diagnoses in the DSM5 come with the word “disorder”

attached. Perhaps all that is needed to help resolve this issue is a more formal name, such as

Perfectionistic Disorder, Clinical Perfectionism, or Anxiety Disorder with Perfectionistic

Features.

Treatment for Perfectionism

6

Research on the clinical treatment of perfectionism has grown dramatically in the past two decades. Interventions featuring brief psychoeducation (Aldea, Rice, Gormley, & Rojas,

2010), transcendental meditation (Burns, Lee, & Brown, 2011), mindfulness-based bibliotherapy

(Wimberley, Mintz, & Suh, 2016), and coherence therapy (Rice, Neimeyer, & Taylor, 2011) have all been used to reduce symptoms of perfectionism significantly. Additionally, theorists have argued for treating perfectionism with various psychodynamic interventions (Brustein,

2014; Greenspon, 2008; Hewitt et al., 2015; Hewitt et al., 2017). Finally, most perfectionism treatment research features cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) interventions. CBT interventions featuring individual therapy (DiBartolo, Frost, Dixon, & Almodovar, 2001; Egan & Hine, 2008;

Ferguson & Rodway, 1994; Glover, Brown, Fairburn, & Shafran, 2007; Hirsch & Hayward,

1998; Riley, Lee, Cooper, Fairburn, & Shafran, 2007; Shafran, Lee, & Fairburn, 2004), group therapy (Handley, Egan, Kane, & Rees, 2015; Kearns, Forbes, & Gardiner, 2007; Richards,

Owen, & Stein, 1993; Steele, Waite, Egan, Finnigan, Handley, & Wade, 2013), manual-based self-help therapy (Pleva & Wade, 2007; Steele & Wade, 2008), and web-based therapy (Arpin-

Cribbie, Irvine, Ritvo, Cribbie, Flett, & Hewitt, 2008; Radhu, Daskalakis, Arpin-Cribbie, Irvine,

& Ritvo, 2012) have all significantly decreased symptoms of perfectionism. Additionally, many of these studies reported that the treatment had a significant effect on measures of depression and/or anxiety (Glover et al., 2007; Handley et al., 2015; Richards et al., 1993; Riley et al., 2007;

Shafran et al., 2004; Steele et al., 2013), eating-disorder symptoms (Handley et al., 2015;

Shafran et al., 2004; Steele & Wade, 2008), and obsessive-compulsive symptoms (Pleva &

Wade, 2007). In a recent review and meta-analysis, Samantha Lloyd and colleagues (2015) concluded that while CBT interventions can significantly reduce aspects of perfectionism in adults with perfectionism appearing as a primary problem or as a problem coinciding with other

7 psychiatric diagnoses , “further research is required to investigate the most effective format of perfectionism interventions” (p. 727).

Overview of ACT

ACT is a transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral therapy with empirical evidence demonstrating it to be an effective treatment for a wide range of clinical problems (Smout,

Hayes, Atkins, Klausen, & Duguid, 2012), including: anxiety (Arch et al., 2012), depression

(Forman, Herbert, Moitra, Yeomans, & Geller, 2007), obsessive compulsive disorder (Twohig et al., 2010), psychosis (White et al., 2011), chronic pain (Wetherell et al., 2011), substance use disorder (Luoma, Kohlenberg, Hayes, & Fletcher, 2012), and disordered eating (Weineland,

Arvidsson, Kakoulidis, & Dahl, 2012). The ACT model views human suffering and maladaptive functioning as a product of psychological inflexibility or rigidity (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson,

2012). Psychological inflexibility has been described as a “ rigid, literal, and inflexible style of responding to internal experiences (thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations)” (Crosby et al.,

2013, p. 144). It is defined operationally by six core processes: inflexible attention, disruption of chosen values, inaction or impulsivity, attachment to a conceptualized self, cognitive fusion, and experiential avoidance. Correspondingly, psychological flexibility is defined as a product of six core oppositional processes: flexible attention to the present moment, chosen values, committed action, self-as-context, defusion, and acceptance (note: these terms explained more fully in

“Treatment Overview”). With the goal of improving a person’s psychological flexibility, ACT

seeks to help a person develop the ability to be mindful of – and adopt an accepting attitude towards – her internal experience and to commit to act consistently with her freely chosen values.

ACT for the Treatment of Perfectionism

Although multiple interventions have proven effective to varying degrees for the treatment of perfectionism, researchers and theorists continue to explore alternative avenues for treatment. Recently, ACT has been identified as a potentially applicable intervention for perfectionism. As a transdiagnostic treatment, ACT seems particularly suitable for a transdiagnostic mechanism like perfectionism (Egan et al., 2012). By definition, transdiagnostic

8 treatments like ACT are designed to target underlying critical processes that maintain a wide range of problems.

ACT views the processes of cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance as the “siren songs” of human suffer ing (Strosahl & Robinson, 2008). Both processes are hallmarks of perfectionism.

“ Cognitive fusion ” is the tendency for humans to get caught up or entangled in their internal experiences such that they respond to these experiences literally, without proper regard for context (Hayes et al., 2012). Crosby and colleagues (2013) write, perfectionists ’ thoughts

“ are characterized by rigid and inflexible concern over mistakes, doubts about actions, evaluation of the discrepancy between achievement and standards, self-cr iticism, and a fear of failure” (p.

144) . Hewitt and colleagues (2017) state, “perfectionistic thinking may be so ingrained for some people that it can be activated automatically as a cognitive filter. However, there is still a role for conscious cognition, in the form of preoccupation with shortfalls and ruminating about imperfections” (p. 57).

“ Experiential avoidance ” refers to any attempt to control, suppress, eliminate, or escape from unwanted internal experiences (Hayes et al., 2012). Perfectionists characteristically utilize

9 experiential avoidance to help control or avoid perfectionistic thoughts, feelings, and/or physical sensations (Crosby et al., 2013; Hewitt et al., 2017). Moroz & Dunkley’s (2015) research

“indicate that experiential avoidance is used to deal or cope with the negative feelings associated with self-critical perfectionism, specifically the harsh self-scrutiny and perceived criticism from others” (p. 178). In multiple studies, it has been demonstrated that perfectionism has a significant relationship with measures of experiential avoidance (Crosby, Bates, & Twohig, 2011; Moroz &

Dunkley, 2015; Santanello & Gardner, 2007).

ACT interventions are designed to explicitly target cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance as well as several other complimentary processes. The treatment overview section that follows provides a further elaboration of how ACT processes are utilized in treating expressions of perfectionism.

Method

Participants

The five participants were students at the university at which the researcher was a therapist in the university’s counseling center. Three students enrolled in the study after seeing a flyer (Appendix F) posted on campus. Two students were already receiving services at the counseling center and were transferred to the study based on a determination by the student and their respective therapist that they were appropriate candidates for this treatment. All students completed a comprehensive intake assessment in-person with the researcher. They were deemed eligible for participation based on a subsequent determination by the researcher and his supervisors that the student had perfectionism as a primary problem or as an underlying feature

10 of a secondary problem for which treatment of the perfectionism was deemed indicated. Notably, all participants met DSM-5 (APA, 2013) diagnostic criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (4 students) or major depressive disorder (1 student) upon entering the study.

Therapist

Therapy was conducted by the author who was in his third year of doctoral training at

Widener University ’s Institute fo r Graduate Clinical Psychology. The therapist was trained in

ACT theory and methods as part of his doctoral education, and had attended ACT workshops conducted separately by Steven Hayes, Frank Masterpasqua, Daniel Joseph Moran, John

Armando, and Dennis Tirch. He was supervised weekly by a licensed psychologist with over ten years of clinical experience practicing ACT and over five years of academic experience teaching

ACT at a doctoral-level clinical psychology program.

Design

A one-group pretest-posttest quasi-experimental design was used. Patients were evaluated at intake to determine appropriate candidacy for the intervention. Measures ( see “Measures” ) were administered at the start and end of treatment. The treatment (see “Treatment overview and core process targets”) was designed to be delivered with the intention of no more than twelve weekly, 45-minute sessions.

Measures

The patients completed the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al., 2011; Appendix A). This 7-item self-report measure was used to evaluate each patients’ psychological inflexibility, or their inability to accept negative internal experiences and pursue meaningful action in the presence of these experiences. Patients rated the extent to which each statement described them on a 7-point Likert scale (scores can range from 7 to 49). It has high

internal consistency ( D =.78-.88; Bond et al., 2011), test-retest reliability (r=.81; Bond et al.,

11

2011), construct validity (Fledderus, Oude Voshaar, ten Klooster, & Bohlmeijer, 2012), and convergent, discriminant, and predictive validity (Bond et al., 2011).

The Short Form of the Revised Almost Perfect Scale (SAPS; Rice, Richardson, &

Tueller, 2014; Appendix B), an 8-item self-report measure, was used to identify patients ’ perfectionism. This measure features two subscales (High Standards and Discrepancy) that seek to capture the essential dimensions of perfectionism: high performance expectations and selfcritical attitudes associated with performance evaluation. Patients rated the extent to which they agree with each statement on a 7-point Likert scale (scores can range from 8 to 56). It has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability ( U =.85, .87 for high standards and discrepancy subscales, respectively; Rice et al., 2014). The measure has high convergent and discriminant validity with other perfectionism measures, including the Revised Almost Perfect Scale and the

Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (Rice et al., 2014).

The Perfectionism Cognitions Inventory (PCI; Flett, Hewitt, Blankstein, & Gray, 1998;

Appendix C), a 25-item self-report measure, was used to identify the frequency of patients ’ automatic thoughts about the need to be perfect and their cognitive awareness of imperfections over the preceding seven days. Patients rated the extent to which they experience each thought

(i.e., from “Not at all” to “All of the Time”) on a 5-point Likert scale (scores can range from 0 to

100). It has high internal consistency ( D =.91; Flett et al., 2012), test-retest reliability (r=.76;

Mackinnon, Sherry, & Pratt, 2013), construct validity (Flett et al., 2012) convergent validity

(Flett et al., 1998), discriminant validity (Flett et al., 2012), and predictive validity (Flett et al.,

2012; Hill & Appleton, 2011).

The Valuing Questionnaire (VQ; Smout, Davies, Burns, & Christie, 2014; Appendix D),

a 10-item self-report measure, was used to evaluate further patients’ commitment to valuesconsistent action. Patients rated the extent to which each statement describes them on a 7-point

Likert scale (scores can range from 0 to 60). It has high internal consistency ( D =.79-.81) and

12 construct validity (Smout et al., 2014).

The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire (CFQ; Gillanders et al., 2014; Appendix E), a 7-item self-report measure, was used to measure the degree to which patients get embroiled in their thoughts such that these thoughts dominate their actions. Patients rated the extent to which each statement describes them on a 7-point Likert scale (scores can range from 7 to 49). It has high internal consistency ( D =.88-.93), test-retest reliability (r=.81), construct, discriminant, and incremental validity (Gillanders et al., 2014).

The Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms-34 (CCAPS-34; Locke et. al., 2012), a 34-item self-report measure, was used to evaluate patients’ level of psychopathology and symptom severity in the areas of depression, generalized anxiety, social anxiety, general distress, and academic distress. Patients rated the extent to which each statement described them on a 4-point Likert scale. It has been shown to be a reliable instrument for both diagnostic assessment and as a measure of treatment progress (Locke et al., 2012). It has high internal consistency ( D =.76-.892), test-retest reliability (r=.742-.866), construct, convergent, and discriminant validity (Locke et al., 2012).

Treatment Overview and Core Process Targets

The treatment program outlined below is arranged in the order in which the described interventions were typically introduced. While all five patients whose treatment is the subject of this paper received ACT-consistent treatment that approximated this guideline, the therapy was delivered flexibly and was not rigidly bound to a specific protocol. Consequently, the order in

which exercises were introduced (or whether they were introduced at all) was determined on a

13 case-by-case basis. ACT is intended to be delivered flexibly, with the therapist cognizant of what intervention seems most beneficial to the patient at any point in time (Hayes et al., 2012). Once a concept was introduced, it became available to be woven into future sessions when indicated. For practical purposes, exercises are listed once under their primary process target. ACT exercises generally are usable to address multiple, if not all, core processes.

ACT introduction and creative hopelessness. Most patients come to therapy with a change agenda. Their internal experiences are unpleasant, and they hope that therapy can help them learn to better control and change these experiences. Perfectionistic patients commonly state, “I just want to feel better,” or ask, “Can you teach me to stop worrying?” ACT treats this desire to cont rol one’s internal experiences as a fundamental contributor to the individual’s suffering (Hayes et al., 2012). As such, it is essential, from the outset of treatment, to help a patient see the unworkability of their efforts to try to control internal experiences, clarify the alternative way that ACT attempts to help them handle these experiences, and receive buy-in to begin treatment utilizing the ACT philosophy.

In this intervention, an ACT exercise called “creative hopelessness” was utilized to initiate this process. The aim of creative hopelessness is to help a patient recognize, from his own experience

, that the strategies he has been using in his life have been ineffective (Hayes et al.,

2012). This goal is accomplished first by helping the patient identify what he has been struggling with, focusing particularly on specific “bad” or “negative” internal experiences. The patient is then asked to identify: 1) what strategies he has been using to try to deal with these experiences;

2) how those strategies have worked; and 3) what is the cost of using those strategies. To illustrate, a common thought process of a perfectionistic student may be : “I sometimes have the

thought that the work I’m doing won’t be good enough or people will think it’s stupid. So, I

14 either spend a million hours working on the thing, making myself crazy, or, if I can, I just decide pretty much right from the beginning not to do it at all. Sometimes this helps me feel better, at least in the short-term. But there are a lot of problems. I spend so much time doing an assignment that I don’t have time for other stuff in my life, including other assignments! Or I feel guilty for not doing something that I know I should have d one.”

Often, the patient will recognize that while their control techniques may provide some short-term benefits, those benefits are outweighed by short- and long-term consequences. Once the patient appreciates the futility of his existing strategies, he is ready for an explicit introduction to ACT. Russ Harris’ (2009) “ ACT in a Nutshell ” exercise provides a way to accomplish this goal metaphorically. Metaphors are generally preferred over traditional didactics and dialogue in the ACT model because they encourage an experiential exploration of issues and are especially advantageous in making abstract concepts quickly accessible (Stoddard & Afari,

2014). The “ACT in a Nutshell” exercise features five sections.

First, a clipboard is utilized to represent a p atient’s internal struggles metaphorically

(alternatively, a large note card can be used and the patient’s previously identified difficult internal experiences can be written on it). The patient is told to hold the clipboard tightly, directly in front of his face, and asked wha t that experience is like. What’s his view of the room like? How much could he accomplish in this state? This part of the exercise helps the patient identify that, while he is focused on his negative experiences, it is difficult for him to connect to the world around him and do things that are important to him.

Second, with the therapist pushing on one side of the clipboard, the patient is asked to attempt to push the clipboard as far away from himself as possible and asked what that

experience is like. For example, how much energy does it take to do this? How much can he

15 accomplish in this state? Here, the patient can identify that his attempt to push away his negative experiences creates the same problems he experienced with the clipboard directly in front of his face.

In the creative hopelessness exercise, the therapist has already helped the patient identify how he becomes consumed by negative experiences (“holding the c lipboard tightly in front of his face) and strategies for fighting or avoiding these experiences (“pushing the clipboard away”).

These specific examples can be woven into “ ACT in a Nutshell ” to improve its salience for the patient.

Third, the patient is told to place the clipboard in his lap and asked what this experience is like. How well can he see and engage with the therapist and his environment? How capable is he of doing things that might be important to him?

Fourth, the therapist acknowledges that surely the patient would prefer not to have these difficult experiences on his lap and would much rather throw the clipboard into the other room.

The therapist then reviews with the patient all the ways the patient has tried to do just that and helps the patient identify that these strategies have been ineffective.

Fifth, the therapist details the alternative path that ACT suggests. The goal is to get the patient to accept or at least be open to the thought that the patient will learn how to handle these difficult internal experiences more effectively so that he can be free to engage in actions that are meaningful to him.

Cognitive defusion. The ACT model is built on the belief that “human suffering predominantly emerges from normal psychological processes, particularly those involving human language” (Hayes et al., 2012, p. 11). Humans have a unique ability to worry: to

continuously scan the environment for threat; to replay and analyze prior experiences; and to

16 make predictions about the future. Primitive humans used their ability to “think negatively” (i.e., to have negative thoughts about their situation) to survive with relatively limited resources in a world of stronger, faster animals. While an antelope presumably stops fearing a lion once it has reached safety, humans can continue to worry endlessly about that lion — and anything that the mind associates with the lion. Although this ability is undoubtedly helpful, it also can be deeply problematic. Since the human mind engages in a threat detection process, it is critical to psychological and behavioral functioning that we have a realistic perspective on that process.

“ Cognitive fusion ” refers to the tendency for humans to get caught up or entangled in their internal experiences such that they respond to these experiences literally, without proper regard for context (Hayes et al., 2012). For example, while giving a hypothetical presentation, a perfectionistic patient may have the thought, “These people think I’m stupid .

” A patient who cognitively fuses with that thought will treat the thought as factually true and respond accordingly.

“ Cognitive defusion ” refers to the ACT process of recognizing and accepting that thoughts are just thoughts, and not factual truths that demand a response. Developing the ability to defuse from thoughts enables a patient to take action consistent with his actual goals. One simple technique for defusion is just to add the phrase, “I’m having the thought that,” to any thought. For example, the patient would be asked to say, “I’m having the thought that these people think I’m stupid.” Ideally, this technique enables the patient to notice his thought as a thought and not as a factually true statement that must guide his behavior.

Various other cognitive defusion techniques were utilized in this treatment (see Harris,

2009 and Hayes et al., 2012 for numerous examples). Additionally, a frequently used daily

17 practice assignment , utilizing the “Getting Hooked” worksheet (Harris, 2009, p. 133), involved a patient noticing when her mind had “negative thoughts” and documenting whether she was

“hooked” (i.e., fused) by the thought or able to “unhook” (i.e., defuse) herself.

Experiential avoidance and acceptance. “ Experiential avoidance ” refers to any attempt to control, suppress, eliminate, or escape from unwanted internal experiences (Hayes et al.,

2012). Like cognitive fusion, ACT views experiential avoidance as an inherent component of human suffering. Taking nearly any patient through the creative hopelessness exercise described earlier is likely to reveal numerous forms of experiential avoidance taken in his life and its similarly numerous destructive effects. In ACT, a patient is asked to learn to accept his difficult internal experiences in the service of constructive, meaningful action. To be clear, acceptance does not

mean passively tolerating or resigning oneself to a situation. It does not mean desiring or liking a situation, nor does it mean judging a situation as right, fair, or just. Acceptance means voluntarily taking an “open, receptive, flexible, and nonjudgmental” attitude towards internal experiences (Hayes et al., 2012, p. 272). When a patient rejects the word ‘acceptance,’

‘willingness’ can be used in its place.

The goal is to enable the patient to be open to experiencing his thoughts, feelings, and bodily sensations, however unpleasant, in the service of taking action consistent with the person he wants to be. Both the creative hopelessness and “ ACT in a Nutshell ” exercises (described above) are utilized in part to introduce patients to the futility of experiential avoidance and to open them up to the idea of acceptance as an alternative path.

The “ Passengers on the Bus ” metaphor (Hayes, Strosahl, & Wilson, 1999), or the

“ Demons on a Boat ” variation (Harris, 2007), is used to help a patient overcome experiential avoidance. Further, this metaphor can act as a framework through which the entire ACT model

can be brought to bear on any situation that presents itself in treatment. In this metaphor, the

18 patient is asked to imagine that he is the driver of a bus. The bus has many passengers, which represent the pat ient’s internal experiences (i.e

., thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, memories).

For example, suppose a perfectionistic patient is “driving” towards the completion of an important goal. The thought, “You’re going to fail!” is one of the pa ssengers. Whenever this passenger speaks up, he’s often joined by his friends: the feeling of fear and the bodily sensation of stomach pain. The patient does not

like it when these passengers speak up. They are very ugly, say horrible things to him, and look as though they could truly harm him. Consequently, when they do speak up, he does whatever he can do to get them to quiet down. Unfortunately, there is no way to get them off the bus, so the patient makes a deal with them: “Okay, I’ll stop working on th is goal if you hide in the back of the bus.” In this c ase, the patient has changed his behavior in hopes of avoiding his unpleasant internal experiences (note the link here between cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance). He is the driver of the bus in name only. His internal experiences are in control. Fortunately, the patient is shown that he has made a common and understandable, but problematic error in judgment. While the passengers on his bus seem like they can harm him in horrible ways, the only thing they can actually do is exist. Whether they harm him or not is his choice. If he can learn to tolerate them standing up and yelling at him, he can drive the bus wherever he wants.

Values-consistent action. In ACT, values have been defined as “state ments about what we want to be doing with our life: about what we want to stand for, and how we want to behave on an ongoing basis” (Harris, 2009, p. 189). They are freely chosen and constructed by the individual and are continually evolving (Hayes et al., 2012). Importantly, “values are not goals or ends in themselves, but can be thought of as principles for living that organize and direct current

action” (Lundgren, Luoma, Dahl, Strosahl, & Melin, 2012 , p. 518). It could be argued that the

19 whole point of ACT is to help a person construct a rich and meaningful, or values-consistent, life. Put another way, the skills of cognitive defusion and experiential acceptance are developed precisely to enable a person to take values-consistent action. Seen through the lens of the

“ Passengers on the Bus ” metaphor, our values serve as our compass, letting us know which direction to drive our “ bus.

”

Clarifying values is an important step in any ACT intervention. Two techniques were predominantly used in this treatment to help patients identify their values: 1) The “Values Bull’s

Eye ” (Dahl & Lundgren, 2006; Harris, 2009; Lundgren et al., 2012), and 2) the “ Imagine Your

80 th Birthday ” exercise (Harris, 2009).

The “ Values Bull ’s Eye ” exercise is a simple, one-page worksheet designed to help a patient identify his values in four key domains: 1) work/education, 2) relationships, 3) personal growth/health, and 4) leisure. The patient is asked to list his values under each domain. This part of the exercise typically requires some prompting on the part of the therapist and some brainstorming on the part of the patient (the “ Imagine Your 80 th Birthday ” exercise, described shortly, can be used to facilitate this process). On the bottom half of the page is a “dartboard” divided into the same four quadrants, with six concentric circles surrounding the bullseye. In each quadrant, the patient is asked to place an “X” on the circle of the dartboard that represents the degree to which he is living his life in accordance with his values (e.g., an X in the center of the dartboard represents living fully consistent with his values in that domain).

This exercise tends to be novel to perfectionists in three ways. First, perfectionists have spent much of their lives fused with the belief that perfection itself is of utmost value. Either its attainment has driven them, or its unattainability has overwhelmed them. The opportunity to

explore what really

matters to them, deep down, is an enlightening and inspiring experience.

20

Second, perfectionists have similarly spent most of their lives with one measuring stick:

“Was I perfect or not perfect? Was I the best or not the best?” The “Values Bull’s Eye” is, itself, a new measuring stick, introducing a new way to evaluate one’s performance: “Did I take a ctions today that are consistent with my values?”

Third, many perfectionists evaluate themselves and their performance based on a desire to win the approval of others. Historically, their behavior has revolved around other people’s values. The “Values Bull’s Eye” asks them to explore what really matters to them .

In the “ Imagine Your 80 th Birthday ” exercise, the patient is asked to indulge in the fantasy that, at 80-years-old, he has lived his own ideal life and that all the important people in this fantasy life, living or dead, are there to attend his birthday party. The patient is asked to imagine that someone (e.g., a friend, child, partner, or colleague) stands up to make a short speech, no more than a few sentences. The patient is told that the person talks about what the patient had stood for in his life, what the patient had meant to them, and the role that the patient had played in his life. The patient is asked to imagine the person saying whatever, deep down in his heart, he would most love to hear the person say. The patient is then told that another person wants to make a speech and then another. The exercise is then debriefed with the patient helped to consolidate what the “speeches” revealed about what the patient values.

Present-moment awareness and exposure. Since the goal of ACT is to enable a person to take values-consistent action in the present moment, an obvious skill that must be developed is the ability to be

in the here and now. In ACT, present-moment awareness, or mindfulness, is defined as “paying attention with flexibility, openness, and curiosity” (Harris, 2009, p. 8). In some ways, this ability to be “mindful” is foundational to all ACT’s core processes.

As such,

21 integrated into all ACT interventions is an attitude of openness and curiosity to present-moment processes.

Present-moment awareness exercises are introduced implicitly in the first session. To understand what brought the patient to treatment, the therapist gets the patient to describe a current situation that exemplifies her broader struggle. As the patient describes her issue, unpleasant internal experiences are generated, and she will likely attempt to stray from presentmoment experience as part of an experiential avoidance process. The therapist guides the patient back to her story, while periodically asking the patient to describe what she is thinking or how she is feeling as she tells it. These exercises serve a myriad of functions, including exposing the patient to her unpleasant internal experiences.

Exposure exercises are a frequent part of treatment, and patients are encouraged to practice them throughout the week between sessions. The previously mentioned “Getting

Hooked” worksheet was utilized to help facilitate this process. Additionally, the “Passengers on the Bus” metaphor was frequently utilized as a conduit to present -moment awareness processes.

For example, the therapist might ask the patient, “What passengers are showing up for you right now?”

Finally, other present-moment awareness exercises were utilized, including: “Take Ten

Breaths” (patient is instructed to take ten slow, deep breaths, while noticing the physical sensations of her body and attempting to let thoughts come and go without hooking her);

“Dropping Anchor” (patient is instructed to stand and push her feet into the floor, noticing the physical sensations of being anchored to the floor and other present-moment experiences); and

“Notice Five Things” (patient is instr ucted to see five things, hear five things, and feel five things) (Harris, 2009, p. 171).

22

Patients were given a handout describing these exercises. They are encouraged to try them daily, doing so at a convenient time of day at first and then at moments when they noticed themselves getting caught up in their thoughts and feelings.

Self-as-context. In ACT, “s elf-as-context ” refers to a “viewpoint from which we can observe thoughts and feelings… a place from which we can observe our experience without being ca ught up in it” (Harris, 2009, p. 173 ). It has been called the “transcendent sense of self, the observing self, noticing self, continuity of consciousness, pure consciousness, [and] pure a wareness” (Hayes et al., 2012, p. 85). It exists in contrast to “ self-as-concept, ” which is “all the beliefs, thoughts, ideas, facts, images, judgments, memories, and so on that form [one’s] selfconcept” (Harris, 2009, p. 174 ). A popular ACT metaphor describes a person’s observing self as being like the sky, and her thoughts and feelings as the continually changing weather (Harris,

2009). Patients presenting for treatment often exist almost exclusively in their conceptualized selves. That is, they believe themselves literally to be

their beliefs and thoughts. In this treat ment, the “ACT in a Nutshell” exercise, “Passengers on the Bus” metaphor, and various mindfulness exercises were utilized to help patients cultivate an awareness of their observing selves.

Self-compassion. Compassion involves noticing another person’s suff ering and having a deep desire to help that person. Most simply, self-compassion is compassion directed towards one’s self and has been operationalized as consisting of three primary components: 1) kindness,

2) a sense of common humanity, and 3) mindfulness (Neff, 2003). Self-compassion has been demonstrated to predict positive psychological health, to associate positively with measures of positive affect, personal initiative, and conscientiousness, and to associate negatively with measures of negative affect and neuroticism (Neff, Kirkpatrick, & Rude 2007). A recent meta-

analysis found “robust, replicable findings linking increased self -compassion to lower levels of

23 mental health symptoms,” including anxiety and depression (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012, p. 55 1).

While self-compassion is not an explicit part of the ACT model, theorists have suggested its consistency with the ACT model (Hayes, 2008; Neff & Tirch, 2013). It also has been explicitly integrated into ACT treatment guides (Forsyth & Eifert, 2016; Harris, 2009; Tirch, Silberstein, &

Schoendorff, 2014).

Perfectionists are often plagued by hostile, punishing thoughts (e.g., “You’re not good enough,” “They all thought you were stupid,” and “Nobody loves you”). Self -compassion exercises can provide a constructive context for engaging with and defusing from those thoughts and enabling values-consistent action.

In this treatment, specific self-compassion exercises were introduced when a patient was identified as needing a new approach for handling her punishing thoughts. A primary exercise involves asking the patient to try to remember the first time she experienced the painful thought that is currently troubling her, and then bringing out the patient’s compassion for that younger version of herself. For exa mple, a perfectionist may be able to identify first telling herself “I need to perform perfectly or nobody will care about me” upon returning home from a sporting event at age 10. This patient is asked to imagine her 10-year-old self as vividly as she can, and then to bring that 10-year-old into the room in front of her. If done well, this exercise helps the patient easily connect with the compassion they feel for that little girl, and, consequently, herself. The patient can then be guided in how best to help that little girl, in an ACT-consistent manner (i.e., acknowledging the little girl’s feelings and providing her with unconditional acceptance and love). An extension of this exercise can be to then ask the patient to visualize a much older, 60year-old version of herself and to imagine that 60-year-old meeting her present-day self. The

patient is typically able to identify that her older self would have the same compassion for her

24 present-day self as she does for her 10-year-old self.

Another exercise utilized in this treatment involves asking the patient to imagine that a friend was having the same struggle that he was having and how he would treat his friend in that situation (Neff, 2016). The patient is helped in identifying strategies that would be most useful to help a friend who was having this experience, and then enabled to put those strategies to good use on himself.

Results and Case Descriptions

Data were collected successfully from all five participants at the time of their first and final visits to the counseling center for participation in this study (see Tables 1 and 2). For every instrument used, a higher score is reflective of maladaptive functioning (i.e., lower scores are more desirable). The study ’s hypotheses that participants would see reductions in perfectionism, perfectionistic thoughts, and symptoms of mental illness, and that participants would see improvements in measures of psychological flexibility were supported. These gains were analyzed by averaging the data from all five participants and conducting paired sample t-tests

(see Table 3). Significant gains ( p

< .05) were found on nearly all measures with concurrent strong effect sizes (Cohen’ s d > .80). Linear regressions revealed that baseline scores on the

SAPS did not predict pre- to post-test changes in perfectionistic thoughts (PCI), psychological flexibility (AAQ-II), or psychological symptoms (CCAPS). A first order correlation revealed no correlation ( r

= .115, p

= .853

) between patients’ pre - to post-test changes in perfectionistic thoughts (PCI) and their changes in psychological flexibility (AAQ-II).

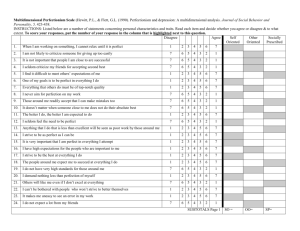

Table 1

25

Pre and Post Data for Psychological Flexibility and Perfectionism Measures

Measure Daniel Sara Chloe Margaret Tamara

Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post

AAQ-II

SAPS

PCI

31 29 25 13 40 31 27 23 28 19

43 42 45 40 40 33 52 47 42 45

67 43 83 60 49 31 66 56 74 60

VQ 37 31 13 12 45 24 23 15 29 19

CFQ 36 35 26 21 45 36 35 29 37 30

Note. AAQ-II=Acceptance and Action Questionnaire, 2 nd edition; SAPS=The Short Form of the

Revised Almost Perfect Scale; PCI=Perfectionism Cognitions Inventory; VQ=Valuing

Questionnaire; CFQ=The Cognitive Fusion Questionnaire.

Table 2

Pre and Post Data for Counseling Center Assessment of Psychological Symptoms (CCAPS-34)

Measure Daniel Sara Chloe Margaret Tamara

Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post Pre Post

Distress Index 43 22 41 17 88 39 31 12 67 45

Depression 58 21 42 21 68 42 42 16 63 58

Generalized Anxiety 41 35 41 20 73 41 35 15 86 52

Social Anxiety 62 48 92 68 95 55 68 35 55 42

Academic Distress 66 44 37 37 89 30 23 23 44 30

Table 3

Pre and Post Data for Group Means

Measure

AAQ-II

SAPS

PCI

VQ

Pre Post p Cohen ’s d

30.2 23.0 .017 1.76

44.4 41.4 .169 0.75

67.8 60.0 .003 3.00

29.4 20.2 .050 1.24

CFQ 35.8 30.2 .013 1.89

Distress Index 54.0 27.0 .008 2.17

Depression 54.6 31.6 .012 1.98

Generalized Anxiety 55.2 32.6 .011 2.01

Social Anxiety 74.4 49.6 .009 2.11

Academic Distress 51.8 32.8 .155 0.78

The Case of Daniel

Daniel (names and identifying details have been changed to preserve anonymity) was a

20-year-old African American male in his 2 nd year of undergraduate education. He was single with married parents and an older brother who lived thirty minutes away. Daniel reported

26 persistent anxiety regarding his ability to perform up to his high academic standards and his ability to navigate social situations. He described an “always racing” mind occupied with selfcriticism and self-doubt about prior and future actions. Daniel traced this anxiety back to lifelong pressure to perform from his demanding father coupled with insecurity about how he compared to his extremely high-achieving older brother. Already pursuing treatment for his anxiety at the university’s counseling center , Daniel was given the recruitment flyer for this study (Appendix

F). He agreed that he would be a good fit and began this treatment for perfectionism.

As Daniel was already a patient in the counseling center, the first session was dedicated to cultivating an understanding of how this treatment would be different from the work he had been doing previously. To this end, the therapist utilized the “ ACT in a Nutshell ” exercise.

Daniel identified his most frequent and distressing thoughts: “I’m not good enough.” “As a black man, I have to be perfect in order to succeed.” “I should have done better.” “What’s the p oint,

I’ll never be good enough.” These thoughts provided insight into the roots of Daniel’s perfectionism. Fro m a very early age, Daniel’s father consistently conveyed the message that, as an African American, Daniel would always be at a disadvantage and that to succeed would mean he would have to achieve at a much higher level than his Caucasian peers. While Daniel believed there was some truth to this message, he felt it had placed too great a burden on him. He explained that he normally handled these burdensome thoughts in various ways, including: ruminating on the thoughts; debating with himself; artificially lowering his standards by deciding

27 that the chal lenging situation didn’t matter; and avoiding challenging situations in various other ways. During a “ Creative Hopelessness ” exercise, Daniel recognized that while his coping techniques often provided short-term stress relief, they ultimately were ineffective. The stress always returned, and he was failing to achieve at a level he knew he could. For example, his 3.25

GPA was below his capabilities, and he was not participating in those activities he knew were essential to his succeeding in his field of study.

In the second session, the “ Demons on a Boat ” metaphor was introduced. Daniel was asked to begin tracking times between therapy sessions when he noticed himself getting “ caught up ” in his difficult i nternal experiences (“demons”) and to notice how that experience effected the choices he made (“the path of the boat”). Because his perfectionistic anxiety manifested in all areas of his life, Daniel was asked to pay particular attention to just one life domain. Daniel chose his academics and identified what values-consistent action in that domain would be for the upcoming week.

In the third session, Daniel reported that the “Demons on a Boat” metaphor had been extremely helpful in enabling him to see how his difficult internal experiences effect his behavior. Though he had made dramatic improvement in recognizing his stress in the moment,

Daniel continued to struggle to take values-consistent action. For example, Daniel stated that in the week prior he had not adequately prepared for a quiz. Daniel identified that his reaction to the thoughts (“Demons”) that arrived when he began to study for the quiz ("This class doesn't matter" and "This book is a waste of time") was to stop studying. This behavior helped him temporarily feel less anxious and avoid the "Demons" that were even deeper down and scarier

("You're going to fail" and "You're not going to achieve anything"). However, on reflection,

Daniel recognized that fusing with these thoughts (i.e., taking them literally and allowing them to

guide his behavior) ultimately contributed to him feeling worse and led to a disappointing

28 performance on the quiz. Daniel’s difficulty was normalized with psychoeducation regarding the sympathetic nervous system’s fight -flight response. He was taught how this is a historically adaptive response that evolved in humans to help us respond to threats such as encountering a lion on the savanna. However, unlike a lion encounter, these internal experiences were not deadly, were not even technically “real,” and could not be dealt with effectively in the same way one would avoid a lion.

Throughout the next few sessions, Daniel was asked to mark his difficult internal experiences in session. Through these exposure exercises he began to make progress in defusing from his negative thoughts and began to recognize that they were not “real” in the same way that a lion is real. Concurrently, his ability to take values-consistent action while having these difficult thoughts improved.

Part of each of the fourth through ninth sessions was dedicated to identifying an anxietyprovoking values-consistent action for Daniel to perform between sessions and then functionally analyzing the experience of undertaking that action. The “Values Bull’ s E ye” and “Imagine Your

80 th Birthday” exercises were utilized to aid Daniel in identifying personally meaningful values in four key life domains.

Daniel was a passionate musician whose music was meaningful to him. He struggled to play creatively although he knew it was essential for his growth as a musician. During the fourth and fifth weeks of treatment, he made playing creatively a nightly goal . Daniel’s tracking sheet evidenced the same anxiety and negative selftalk each night (e.g., “This isn’t very good,” “You aren’t clever,” and “This is a waste of time”). However, he committed t o playing nearly every night and reported being very pleased with himself following his playing. He was progressively

more capable of “losing himself” in his music.

29

In the sixth week of treatment, Daniel reported anxiety about participating in a voluntary campus-wide art competition, where the task at hand involved creating a performance that would be displayed to an audience and judged on its merit. With the submission deadline approaching,

Daniel would have ideally started this project much earlier, but he was paralyzed by various perfectionistic thoughts (e.g., “N obody is going to like what you do, ” “Your ideas aren’t good enough, ” and “These competitions are stupid”).

In the sixth and seventh weeks of treatment, Daniel was encouraged to practice defusing from those thoughts and let his values “drive his boat” (i.

e., guide his behaviors) rather than his goals (i.e., creating a masterpiece and winning the competition). Ultimately, Daniel completed his project. He reported that, although his participation was anxiety-provoking and he did not win the competition, he was proud of the work he had done, had learned a lot by doing so, and had found the experience “more fulfilling than anything I’ve done in a while.”

In the final weeks of treatment, Daniel’s goals range d across domains. These included studying for exams and participating in social activities with classmates.

In Daniel’s 10 th and final session, he reported pleasure in his newfound ability to take values-consistent action despite difficult internal experiences. He stated satisfaction with the progress he had made. An agreement was reached that it was time to end treatment.

The Case of Sara

Sara was a 23-year-old Caucasian female in the second year of undergraduate education.

Born in the United States, but having lived abroad with her parents and siblings for most of her life, Sara had recently returned to the U.S. to commence her secondary education. She was happily married and had an infant daughter.

30

Early in her intake session, Sara reported uncertainty about committing to treatment and great discomfort talking to people, including the therapist, about herself. However, having seen the recruitment flyer (Appendix F), she recognized herself in its description of a perfectionist and was hopeful for some help. Sara successfully maintained a 4.0 GPA, but she was experiencing growing anxiety about her ability to be both a “perfect student and a perfect mom.” In describing the balancing act dictated by her very busy life, she stated, “if I let down a smidge, I will fail.”

On exploration, Sara revealed that failing meant having to abandon her academic pursuits. She dreamt of a life that included a successful career and a family with children.

However, Sara had been raised in a culture in which women predominantly worked as homemakers and caretakers. Although her own parents and husband were uniformly supportive of her professional aspirations, Sara had developed a core belief that her desire to “have it all” was a near-impossible dream and that she would have to be “perfect” to achieve it.

Consequently, any indication that she was falling short of her high standards was a warning sign to Sara that she was at risk of losing her dream. Signs that she was falling short included all internal experiences of stress, which Sara interpreted as weakness and found intolerable. Sara had no outlet for these concerns, as she never acknowledged her insecurities to others. Fearing that her loved ones would interpret her insecurities as weakness and attempt to persuade her to give up on her academic pursuits, she kept these concerns to herself. Consequently, she often felt misunderstood by her friends and loved ones. Having never complained or evidenced her struggles, people seemed to believe that everything came easily to her. On the contrary, Sara was an extremely diligent worker. Sara increasingly found it difficult to avoid or contain her anxiety, which led to her apprehensively entering treatment.

Though Sara had presented for treatment voluntarily, she was extremely hesitant to

engage in and commit to treatment. In the second session, to help Sara reconcile her

31 ambivalence, a creative hopelessness exercise was used in which she was asked to: 1) explore the various methods she had historically utilized to cope with her anxiety and 2) evaluate how well those methods were working. In addition to providing clear motivation for treatment, this exercise opened the door to a discussion about Sara’s willingness to discuss the difficult internal experiences that were challenging for her. At the outset of the third session, Sara declared a willingness to commit to continuing treatment, but she stated that she did not want to talk about difficult or unpleasant thoughts and feelings. Sara’s desire to avoid her distress was normalized with psychoeducation about the sympathetic nervous system’s fight -flight response, which was presented as a historically adaptive response that evolved in humans to help us respond to threats such as a lion encounter on the savanna. The therapist explained to Sara that unlike a lion confrontation , these internal experiences were not deadly, were not even technically “real,” and could not be responded to effectively in the same way one would a lion. Expanding on some of the work she had done earlier, she worked through each of these statements to determine their accuracy. Sara agreed that they were accurate and for the first time began to defuse from her unpleasant internal experiences. The lion-in-the-savanna analogy helped Sara more willingly look at and talk about her perfectionistic thoughts and feelings, and she seemed ready for an insession exposure exercise. Sara was asked to identify a current thought that made her anxious

(“I’ll have to choose between being a mom and being a professional”) and the whole-body experience of having that thought. After some time noticing the discomfort that the thought engendered, Sara was asked to compare the thought to an actual, real-life lion walking into the room. Encouraging Sara not to dispel or contradict her thought, she was asked simply to keep the thought while also recognizing how different it was from a real-life lion. Using a classic defusion

32 exercise, Sara was asked to say, “

I’m having the thought that

I’ll have to choose between being a mom and being a professional” and to notice the difference. Following the exercise, Sara reported that she found the exercise very interesting. She was encouraged to try to notice her anxious thoughts between sessions, and, if she could, to try to defuse from the thought rather than try to suppress it or escape it. These in- and between-session anxiety exposure exercises continued to be utilized in the ensuing weeks of treatment and helped Sara begin to learn how to mindfully notice and cognitively defuse from her distressing thoughts.

In the fourth and fifth sessions, values identification work (i.e., the “Values Bull’s Eye”) was utilized to help Sara clarify what was important to her. Sara highly valued being a loving mother, wife, sibling, and friend. Additionally, she valued being intellectually stimulated, having a career that made a difference in the world by helping people, and being someone that younger women would look up to. Sara was impressed by the realization that it was not actually that important or meaningful to her to do any of these things perfectly and that there was no

“mountain to climb” to achieve being the person she wanted to be. She could be the person she wanted to be (i.e., a person living in a way that was consistent with her values) at any moment.

In a particularly potent exercise, Sara was asked to imagine two possible lives. In both lives she was living in a values-consistent way in the domains of relationships, personal growth/health, and leisure. However, in one life she had no career and in the other she did. Sara stated that she would not be happy or fulfilled with a life without a career. Referring to her current life as a student and a future life as a professional in her field, Sara stated, "I love it, want to do it, enjoy it, and am passionate about it." Clarifying how important, satisfying, and achievable a life with a career was to Sara, helped her begin to believe that achieving that life was not as precarious or impossible as she had long believed. Sara began to realize that, even

though she would often fall short of being “perfect” and that these times may be emotionally

33 difficult for her, she could still fulfill her dreams.

In the fifth and sixth sessions, the “Passengers on the Bus” me taphor was introduced and utilized to help provide a conceptualization of Sara’s relationship with her challenging thoughts

("passengers") and her values-based vision for her future (where she's driving her "bus"). Sara identified frequent thoughts that pertained to her fear of losing her career (e.g., "You'll give up if you have too much fun," "If you express your fears or vulnerabilities to other people, they will push you off your path," and "Be extremely careful, this could fall apart easily") and ways in which these thoughts affected her behaviors (e.g., not having fun, not being open with people in her life, and a broad sense of insecurity/fragility). Sara practiced applying this metaphor in and between sessions. She began to cultivate an ability to notice distressing internal experiences in the moment, acknowledge them for what they were, identify her values and supports (which included her work ethic, resilience, persistence, strong support network of family and friends, and strong anchoring in her religious faith), and then make a conscious decision to take valuesconsistent action.

In the seventh and final session, Sara reported experiencing “confidence and relief.” She stated a newfound awareness of being in control of her life. She acknowledged that she used to

“push bad thoughts a way” and “feel bad for having certain thoughts,” but that she had become more comfortable with these internal experiences and felt confident in her “strength and ability to face them.”

The Case of Chloe

Chloe was a 21-year-old African American female in the 4 th year of undergraduate education. Chloe was single, with separated parents and a younger brother who lived two hours

away. She had been in treatment with different therapists for several years with complaints of

34 depression and anxiety, but she had experienced limited progress on these issues. Having seen the recruitment flyer (Appendix F), Chloe, with the agreement of her former provider, elected to enter this treatment for perfectionism.

As Chloe was already a patient in the counseling center, the first and second sessions were dedicated to cultivating an understanding of how this treatment would be different from her previous therapy. This explanation was achieved by utilizing the “ACT in a N utshell ” exercise.

Chloe identified her most frequent and distressing thoughts: “I’m not good enough,” “I’m afraid

I might fail,” “I’m going to fail,” “I should just give up.” She then clarified that she normally handles these thoughts in various ways, including: distracting herself with video games and the website YouTube; not participating in something if she thinks she might do poorly; and

“endlessly” ruminating on how she should have done or should do something. As part of a

“ Creative Hopelessness ” exercise, Chloe recognized that while her coping techniques often provided short-term stress relief, they ultimately were ineffective. The stress always returned, and she was failing to achieve at a level she knew she could attain. For example, her 3.45 GPA was beneath her capabilities and her frequent procrastination and avoidance contributed to a feeling that s he was “meandering through life.”

In the third and fourth sessions , Chloe’s extreme avoidance of internal experiences emblematic of her perfectionistic anxiety was targeted by in-session exposure exercises. She frequently attempted to change the topic of conversation — often speaking very rapidly and tangentially — any time her internal anxiety was triggered. Chloe was gently interrupted, guided to see this behavior as an avoidance technique, and encouraged to experience her “ anxiety ” without trying to change it. Her difficulty in this task was validated and normalized with

education on how the brain has evolved to be the ultima te “don’t get killed machine,” (Harris,

35

2009, p. 101) using the example of early humans having to respond to extreme threats like a lion on the savanna. Chloe was helped to realize that while her thoughts were indeed distressing, they were not deadly, were not even technically “real,” an d could not be dealt with effectively in the same way one would a lion. Various defusion exercises were employed to help Chloe cultivate an ability to disengage from her thoughts . The “Demons on a Boat” metaphor was introduced to help Chloe begin to concep tualize how her sometimes painful internal experiences (“demons”) altered her behaviors (“the path of her boat”). Chloe was asked to begin tracking times during her day when she felt particularly consumed by her distressing thoughts. She was instructed to note what triggered these thoughts and how they ultimately affected her behavior.

Part of each of the fifth through eleventh sessions was dedicated to identifying an anxiety-provoking, values-consistent action for Chloe to take between sessions and then, at a later session, functionally analyzing her experience of undertaking that action. The “Values

Bull’s Eye” exercise was utilized in helping Chloe identify her values in four central domains of living. Her short-term goals included completing her academic assignments with enough time to do high quality work and attending a resume-building workshop and job fair. Over time, she developed the skill of noticing her negative self-talk in the moment and choosing to commit to a valuesconsistent action. Reflecting on the work she had done on a term paper, she stated, “I started procrastinating and believing the ‘You’ll get it done eventually’ demon, but I knew that the quality of the paper would suffer, or that I might not even get it done. I was down for a minute, but I didn’t give up. I kept doing it , and it came out well.” As Chloe’s mindfulness and defusion skills improved, she noticed that she seemed to lack time management skills, perhaps due to a life spent avoiding challenges through procrastination. Happily, she found the use of a

scheduler on her phone and a proactive approach to planning her week very helpful.