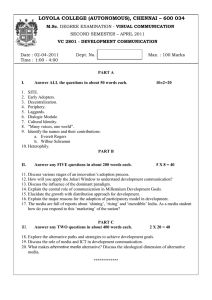

PGCE Primary (3-7) 2014-2015 Module Title and Number Learning and Teaching PDE721 Does dialogic teaching support children in the Early Years Foundation Stage develop their knowledge and understanding of the elements included in the aspect entitled ‘The World’? Submission Date: January 16th 2015 Justification Word Count: 272 Essay Word Count: 2364 1 Essay Justification I have chosen to include three specific elements within this essay which are areas that I have a special interest in. My background is in early years and I am passionate about providing children with the best opportunities from an early age. I understand the importance of having high quality teaching at this stage to give children the foundation on which to build all future learning. I am also hoping to develop a specialism within science, as this is a subject that I really enjoyed and excelled in at school, mainly due to its practical nature. I personally prefer to learn by doing and experiencing things first hand and want to try and encompass elements of that into my own teaching practice wherever possible. Therefore I have chosen to look at the aspect of ‘The World’ that is part of the ‘Understanding the World’ Specific Area within the Early Years Foundation Stage which has strong links with science in the National Curriculum. I am also keen to keep abreast of new and forward-thinking teaching practices to support the development of my teaching career. Dialogic teaching, although not necessarily a new concept, is a pedagogy that moves away from traditional transmission teaching, incorporating elements that support children’s higher level thinking and gives them the power to influence their own learning. I am enthusiastic about giving children the opportunity to take ownership of their own learning and strongly believe that this keeps children motivated and enthusiastic. Therefore I have decided to research the dialogic teaching approach further so that I may be able to apply it to my own teaching repertoire during my career. 2 Does dialogic teaching support children in the Early Years Foundation Stage develop their knowledge and understanding of the elements included in the aspect entitled ‘The World’? The concept of dialogic teaching is not a new one; it has its basis in many different theories and has links with teaching styles of Socrates (Reinsmith,1992, p. 94). The recognition that speaking and listening skills underpin all future learning has been gathering momentum over the last decade with Robin Alexander at the forefront of the movement (Alexander, 2004) but dialogic teaching is not a method to be applied as and when the teacher sees fit (Alexander, 2010); to be effective the teacher must consider it more as their teaching style, an all-encompassing pedagogy that applies to every element of teaching. The Letters and Sounds (DFES, 2007) document was introduced in 2007 to support the integration of systematic synthetic phonics into schools and early years settings, following the recommendations of the Rose Report (BBC News, 2007). The Rose Report also went on to stress the importance of speaking and listening skills as the foundation to reading and writing (Rose, 2006, p. 23). It’s introduction, particularly that of the phase one section, demonstrates the move towards an approach that acknowledges the importance of early speaking and listening skills as the foundation on which to build children’s literacy and therefore, ultimately all other aspects of the curriculum (Rose, 2006, p. 10). Within the revised Early Years Foundation Stage (EYFS), which came into effect in September 2012, ‘Communication and Language’ has been highlighted as one of 3 prime areas, recognising that these prime areas are fundamental for the development of future learning (Early Education, 2012, p.4). ‘Characteristics of Effective Learning’ are also included in the EYFS which include a specific section dedicated to children thinking creatively and critically. In this essay I will be looking at whether the dialogic teaching approach can support children in the EYFS to have a better understanding and knowledge of the specific aspect of ‘The World’. It could be argued that most effective practitioners and teachers already use the dialogic teaching approach; it is not uncommon for good 3 teachers to answer a pupils question with a question. But is this the sum total of the dialogic teaching approach? Dialogic comes from the word dialogue which means to take part in a conversation or discussion (Oxford University Press, 2014), yet, as Cox (2012) and Smith and Otway (2012) suggest, dialogic teaching is as much about listening, giving time for thought and provoking deeper, more meaningful thought processes, as it is about talking (pp.45-62). Alexander (2010) identifies four teaching repertoires used in the dialogic pedagogy, which can be used flexibly. He also identifies five principles which must remain constant. The dialogic teaching approach is collaborative, working together towards a common goal; it is reciprocal, all children and adults must be prepared to listen, share and consider other points of view; and it is supportive, children must feel they can express themselves; it is cumulative, ideas should be combined; and it is purposeful, it should be planned with a clear learning goal. When establishing dialogic teaching, children must feel secure; it must be clear to them that it is acceptable to get things wrong, that it is a safe learning environment where they will not be laughed at or ridiculed for not getting it right. Children should be encouraged and supported to ‘have a go’, share their thoughts, and that their thoughts, suggestions and answers will be valued. Children need to feel empowered (Alexander, 2010) as dialogic teaching is about co-constructing knowledge; working together, sharing thoughts and ideas, putting the pieces of everyone’s thoughts together to see a bigger picture. I worked with children in the EYFS for many years and I would argue that the majority of children feel less inhibited about sharing their ideas, having less concern about other children’s perceptions. However, this isn’t always the case and some children will need to be carefully prepared for, and supported during, dialogic teaching, perhaps using teaching assistants to help them share their thoughts and ideas until they are ready to do so themselves. In my experience, many younger children are able to think quite creatively in their early years of education and more than happy to share their thoughts. As children progress through school they are inducted in to the school norms for teaching, the teacher’s role, peer expectations, the pupil’s role and expected types and methods of pupil response. These expectations and roles can impede children’s willingness to share what might be seen as ‘out of the box’ thinking. Jerome Bruner (1915 present) felt that children should be active participants in their own learning 4 (MacBlain, 2014, p. 52), which corresponds to the dialogic teaching approach, moving away from the idea that children are taught by the teacher, and advocating the teacher as the facilitator of learning. Dialogic teaching has strong links with a range of theorists. The earliest links have be established between the teaching methods of Socrates, whereby he would challenge his students through the use of carefully constructed questions designed to create a learning environment that would allow the pupils to develop their abilities to think both creatively and critically (Fisher, 2013, p.126). By actively guiding students towards a deeper level of thought, teachers can support children to move towards the higher levels of Bloom’s ‘Taxonomy of Cognitive Goals’, supporting their ability to analyse, synthesize and create their own ideas and opinions, thereby creating meaningful and lasting connections about that which they are learning (Krathwohl, 2002, p228). Dialogic teaching, by its very nature, must include an element of socialization. Lev Vygotsky (1896-1934) theorised that socialization and language played an integral role in cognitive development (Farnan, 2012, p.77); he hypothesised about the ‘Zone of Proximal Development’, a method by which children are supported to build on prior knowledge or skills by an adult or knowledgeable peer, therefore using social interaction as a means for development. Dialogic teaching, if used effectively, could support children in taking their next steps in thinking by asking open ended questions, encouraging reflection, evaluation and creative thinking, and includes opportunities to learn from more knowledgeable peers.. Barnes introduced the concept of ‘exploratory talk’ in his seminal text ‘From Communication to Curriculum’ in 1975 (Edwards and Jones, 2001, p.1). His influential writings went on to spur a slew of research including Fletcha’s theory of dialogic learning (2000) and Wells’ theory of dialogic enquiry (1999). Both pointed towards an innate predisposition to using dialogue as a means to establish a wider knowledge and understanding of the subject of discourse. If the foundation of the dialogic pedagogy is learning though discourse it can be reasoned that not only will this support speaking and listening skills but also other literacy aspects such as vocabulary. Hargrave and Sénéchal (2000) completed research that seems to validate this hypothesis, however, their sample group was 5 very small, containing 36 preschool children, therefore more extensive research would need to be conducted before this could be claimed with any certainty. Using the dialogic teaching approach can be linked to many of the Department for Education’s Teachers’ Standards (2011) including: promoting good progress and outcomes… setting high expectations which inspire, motivate and challenge pupils… [and] adapting teaching to respond to the strengths and needs of all children (pp. 10-11). When looking at the quality of teaching it is important to consider the impact of any new initiatives. The Education Endowment Foundation (2014) has amassed a wide range of mainly UK based, high quality studies into oral language interventions which appear to demonstrate a consistent and positive impact on children’s educational attainment. The dialogic teaching approach can be categorised as an oral language intervention with its roots in collaborative learning which the Education Endowment Foundation have also gathered promising research data on. The research also seems to show that the costs of both such initiatives are relatively low. Using the dialogic teaching approach in the EYFS to support children’s understanding and knowledge of the aspect ‘The World’ may help them to understand what, potentially can be very difficult concepts to grasp. This particular aspect of the EYFS incorporates elements such as living things and growth, decay and change (Early Education, 2012), which can be observed in the wider class room environment with careful planning. Nevertheless, just because a child has been able to observe, and perhaps describe or recall their observations, does not mean that they will have understood what they have seen. Using carefully planned dialogic teaching to explore what children think might happen, why they think something is happening, what they already know and introducing key information to stimulate discussion further, can only work towards enhancing their learning experience. Within the EYFS class room, a dialogic environment can allow the teacher to identify misconceptions and support children to ‘rewrite’ their own preconceptions in a meaningful way. Dialogic teaching will also provide opportunities for assessment which will allow the teacher to plan for next steps in learning. It could also be argued that through dialogic teaching, children will be able to synthesise ideas, incorporating 6 the viewpoints of others and reinforce and clarify their own thoughts, making them more coherent and meaningful. The dialogic teaching approach can also be seen as having clear connections with the EYFS characteristics of effective learning in particular the ‘Creating and Thinking Critically’ component where emphasis is put upon children to be able to problem solve, review, predict, notice patterns and plan. These all have their basis in a level of thought that needs to be fostered in young children, which can be done through the effective use of the dialogic teaching pedagogy. If children are actively encouraged to really think, with the use of high level questioning, they will be able to apply this type of thinking throughout their school experience and beyond. ‘Executive function’ is a term that is becoming more familiar with early years educators across the UK. Although there seems to be little by way of a definitive explanation of all the elements that the term ‘executive function’ covers (Meltzer, 2010, p.2) it is clear that a high level of executive function allows for individuals to have extremely effective self-control, motivation, problem solving and rational decision making skills (Bee and Boyd, 2009, p.255). My experience of the EYFS includes specific methods used to support the development of children’s executive function including one example where children were being encouraged to think about a question of the day as part of their self-registration, for example ‘would you prefer to swim at the bottom of the sea or visit the moon?’. Children would use their name to answer the question and then they would be encouraged to talk about why they had made their choice. Self-control is also often a focus in good EYFS settings, with children encouraged to talk about how they are feeling in challenging situations, and being supported to wait, share and take turns. The dialogic teaching approach, if used successfully, can draw on, and support the development of elements of executive function such as decision making and problem solving. Of course, it could be argued that the use of dialogic teaching could lead to unpredictable results, and it is important for the teacher or practitioner to be ready to tactfully address misconceptions as they arise. This can be done by asking children to think about why they have come to that conclusion, asking them to think about other viewpoints that may have be raised, or draw upon the information the group has already gathered. This process in itself, can lead to a range of rich learning 7 opportunities for all involved (Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2009, p.17). In conclusion, I feel that, if implemented correctly, with a comprehensive understanding of the ethos of the dialogic teaching approach, it can be successfully used to support children in the EYFS have a better understanding and knowledge of the aspect entitled ‘The World’. The concepts included in ‘The World’ aspect of the EYFS are challenging but integral to future learning, and the children we teach deserve to have the opportunity to take the time and space they need to fully understand them. Dialogic teaching steps away from the tokenistic teaching that can sometimes be used to ‘tick the boxes’ of the criteria teachers need to meet in an ever increasing workload. It is clear that dialogic teaching is not just about speaking and listening skills; it goes beyond that by supporting children’s ability to think at a deeper level (Wolfe and Alexander, 2008, p.1.). Children need to be challenged to do more than recall or describe what they have seen or experienced to be able to truly understand it. Dialogic teaching may not be immediately successful; it will take time for the children, and supporting adults, to really make the most of the opportunities that a dialogic learning environment provides. Challenges arise when considering how to differentiate for children with additional communication needs such as English as an additional language, special educational need or disabilities, however it could also be said that many children who find it difficult to express themselves using spoken English have a greater understanding than they are given credit for, and therefore it is important that in these circumstances, children should not feel pressured in to giving a spoken response, but also that adults should continue to talk to them with the expectation that they will respond when they are ready and that this could be at any time (DfE, 2007, pp. 2-8). Dialogic teaching needs to be properly planned and structured using the principles and repertoires identified by Alexander (2010), but that doesn’t mean the teacher or practitioner should know everything before the children do. I am excited at the idea of implementing dialogic teaching, not just in the EYFS, but throughout my teaching career with any age group, but the prospect of entering the class room without being fully prepared with all the knowledge I need to ‘teach’ the children for that day, is daunting to say the least. Nevertheless, it is important that the dialogic approach is a shared experience and that whomever is implementing the approach, even if it is me, 8 is not afraid to say ‘I don’t know.’ as long as they are prepared to follow that up with ‘How can we find out?’. 9 References Alexander, R. (2010). Dialogic Teaching Essentials. Retrieved from https://www.nie.edu.sg/files/oer/FINAL%20Dialogic%20Teaching%20Essentials.pdf Alexander, R. (2004, January 30). Talking to learn. TES Newspaper. Retrieved from https://www.tes.co.uk/article.aspx?storycode=389939 BBC News. (2007). Reading System Goes into School. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/6765287.stm Bee, H., & Boyd, D. (2009). Lifespan Development (5th ed.). United States: Boston : Allyn and Bacon, c2002 Cox, S. (2012). Approaches to Learning and Teaching. In A. Cockburn & G. Handscomb, Teaching Children 3-11: A Student’s Guide. (pp. 45-50). United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd. Department for Children, Schools and Families. (2009). Learning, Playing and Interacting; Good practice in the Early Years Foundation Stage. (p.17). Nottingham. DCSF. Department for Education. (2007). Supporting Children Learning English as an Additional Language; Guidance for Practitioners in the Early Years Foundation Stage. (pp. 2-8). Retrieved from http://www.northamptonshire.gov.uk/en/councilservices/children/early-learningchildcare/Documents/PDF%20Documents/Supporting%20children%20EAL.pdf Department for Education. (2011). Teachers’ Standards. Guidance for school leaders, school staff and governing bodies. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/30110 7/Teachers__Standards.pdf Department for Education and Skills. (2007). Letters and Sounds: Principles and Practice of High Quality Phonics. London. HMSO. Early Education. (2012). Development Matters in the Early Years Foundation Stage. (p.4).London. Early Education. Education Endowment Foundation (2014). Collaborative Learning. Retrieved from http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/toolkit/collaborative-learning/ Education Endowment Foundation (2014). Oral Language Interventions. Retrieved from http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/toolkit/oral-language-interventions/ Edwards, JA. & Jones, K. (2001) Exploratory Talk within Collaborative Small Groups in Mathematics. (p. 1)Winter, J. (Ed.) Proceedings of the British Society for Research into Learning Mathematics 21(3) 10 Farnan, R. (2012). Educational Psychology. In J. Arthur & A. Peterson, The Routledge companion to education. (p.77). United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis. Fisher, R. (2013). Teaching Thinking (4th ed.). (p.126). United Kingdom: Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd. Hargrave, A., & Sénéchal, M. (2000). A Book Reading Intervention With Preschool Children Who Have Limited Vocabularies: The Benefits Of Regular Reading And Dialogic Reading. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 15(1), 75–90. doi:10.1016/s0885-2006(99)00038-1 Krathwohl, D. (2002). A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy: An Overview. (p.228).Theory Into Practice, 41(4), 212–218. doi:10.1207/s15430421tip4104_2Oxford University Press. (2014). MacBlain, S. (2014). How children learn. (p. 52). United Kingdom: Sage Publications Ltd. Meltzer, L. (2010). Executive Function in Education: From Theory to Practice. United States: Guilford Publications, Inc. Oxford Dictionaries, Language Matters. Retrieved from: http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/dialogue Reinsmith, W. (1992). Archetypal Forms in Teaching: A Continuum, Vol. 56 (p. 94).United States: Greenwood Publishing Group, Incorporated. Rose, J. (2006). Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading: Final Report. Nottingham: DfES Publications. Smith, J., & Otway, M. (2012). Talking in Class. In A. Cockburn & G. Handscomb, Teaching Children 3-11: A Student’s Guide. (pp. 51-62). United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd. Wolfe, S. & Alexander, R. (2008). Argumentation and Dialogic Teaching: Alternative Pedagogies for a Changing World. (p.1). Retrieved from http://www.beyondcurrenthorizons.org.uk/argumentation-and-dialogic-teachingalternative-pedagogies-for-a-changing-world/ 11 Bishop Grosseteste University PGCE Primary (3-7) 2014-2015 Module Title and Number Learning and Teaching PDE721 Can using Mantle of the Expert support children in year two to understand and apply different writing techniques for information texts? Submission Date: January 16th 2015 Student ID: B1402804 Justification Word Count: 273 Essay Word Count: 2375 1 Essay Justification For my essay I have chosen two key topics; Mantle of the Expert and information texts in year two. I am passionate about keeping my teaching innovative, and developing my repertoire of skills to help me do this. I want my pupils to feel motivated, engaged and to take ownership of their learning. To be able to do this I need to research and understand key teaching pedagogies so that I am able to apply them to my own teaching practice. Having seen some drama based learning, and its impact on the children in my year two class, I decided to do some further reading around this style of teaching. My reading led me to learn about Mantle of the Expert and I felt that this was a style of teaching that my pupils could really get enthusiastic about. I am also keenly aware of my responsibilities to do my best to support children to reach their full potential, and my previous research into gender differences in education, and engaging boys in their learning, has heightened my understanding of some of the key factors effecting boy’s literary attainment. I have recently been working on information texts with my year two class, and I am aware that I need to develop my own knowledge of this area further to ensure I can deliver lessons accurately. I did observe that the children engage much better with these lessons when there was an element of imagination such as when we wrote instructions for making super hero potions. It is for this reason that I have decided to include the element of information texts in the essay. 2 Can using Mantle of the Expert support children in year two to understand and apply different writing techniques for information texts? At first glance, Mantle of the Expert (MoE) could be dismissed as merely role play; at worst, a distraction from the curriculum, at best, a method that could be used to cover the drama that is briefly mentioned in the National Curriculum in England Framework Document (Department for Education, 2013, pp. 28-30). Many teachers may recoil at the prospect of having to take part in drama with their pupils. MoE is much more than drama or role play. It has the potential to be engaging, inspirational; to reach children who have switched off to traditional teaching and learning methods. MoE is an approach to learning that utilises something that comes naturally to many children; imagination. The power of imagination allows children to engage on a level not often seen in the classroom. As stated by Beard and Wilson (2006, p.267) ‘imagination is one of the most powerful mental tools we have at our disposal’. Dorothy Heathcote first coined the phrase ‘Mantle of the Expert’ in the 1980’s but the subsequent introduction of the National Curriculum, the Literacy and Numeracy strategies and the move back towards more traditional methods of teaching meant that her work was largely undiscovered until more recently (Bolton, 2003, p.177), prior to that there had been a level of autonomy hard to envision in today’s teaching sector (Alexander, 2013, p.3). Heathcote highlighted the benefits of using MoE as a multi-layered method of teaching and learning that encompassed a number of elements; Abbott describes three specific modes of teaching (as cited in Fraser, Aitken and Whyte, 2013, p.36) that the teacher needs to be adept in to be able to successfully implement MoE; drama for learning, inquiry learning and expert framing. Heathcote, Bolton and O’Neill (1995) identified six core elements for the practice of MoE, which have been subdivided by Aitken et al. (2013, p.39-41) to include a further four more elements. Although the core elements are essential to the purposes of planning and implementing a successful MoE, for the purposes of this essay I will be considering the impact of inquiry and collaborative learning, shared power and expert framing, and the role of drama for learning. MoE has substantial links to several key learning theories including social constructivism and the pragmatist learning philosophy, with which John Dewey(1859-1952) is often associated (Education Portal, 2014). Dewey proposed that learning should take part within a real life context whenever possible, theorising that children needed to learn from their experiences (Sprung, Froschl and Gropper, 2010, p.45). Dewey also proposed that learning should be a mutual experience 3 between students and teachers and that it was essential that this was done in an environment that promoted equality for everyone that was involved (Arthur, 2012, p.15). He also felt strongly about interdisciplinary curriculums where subjects are not taught independently, but interwoven and accessible to children in a way that reflects their individuality, whilst still providing support and direction (MacBlain, 2014, p.21). Parallels can be drawn between Dewey’s pragmatist philosophy and the social constructivist theories of Lev Vygotsky; both Dewey and Vygotsky highlighted the importance of active participation from the learner and the social aspects of learning (Boyd and Bee, 2009, p.38). Social interaction and active participation are an essential element of MoE. Although MoE could theoretically be planned with one specific subject in mind, in any MoE there is ample opportunity to cover several elements within the curriculum from ICT, English and maths to art, science and geography, thus linking with Dewey’s philosophy on an interdisciplinary curriculum. The New Zealand curriculum, ‘Te Whariki’, is known internationally for its forward thinking and holistic approach to early years. The national curriculum for New Zealand’s school age children clearly links with Te Whariki and also utilises a holistic approach including values and key competencies which encompass thinking, inquiry, equity, communicating, participating and contributing (Ministry of Education, 2007, p.7). The curriculum outcomes from early years, through statutory schooling and beyond are clearly identified as supporting children to grow into confident, connected and actively involved adults who are lifelong learners (Ministry of Education, 2007, p.42). These competencies, values and outcomes can be seen as having clear equivalences with Dewey’s philosophies and Vygotsky’s learning theories. The MoE experience, if used effectively, could support many of these fundamental aspects of growing and learning which seem to garner less prominence in the National Curriculum for England. Although I have had no personal experience of MoE in practice, I have seen drama for learning in use in my recent placement with a year two class. In their topic work, ‘Our Super Selves’ the class was contacted via video link by ‘Captain America’. The children spoke with ‘Captain America’ at length about being a super hero and asked a range of questions. This was then followed up with letter writing to ‘Captain America’. The children were captivated and the letter writing quality demonstrated a commitment to trying their hardest regardless of their level of literary attainment. Although there are several key elements missing from this experience to relate it directly to MoE, it was clear to me how inspirational the drama aspect could be to teaching. The children were totally engaged and the experience fed into their role play in the playground; they spoke about ‘Captain America’s’ video call for weeks. If such a small element of drama can have such a significant impact on the children’s enthusiasm and engagement, I can only speculate how they would respond to a full MoE experience if properly planned and implemented. In this experience the children were supported in learning the key features of letter writing and then implemented that knowledge by composing their own letters to ‘Captain America’. I 4 propose that during one or more, thoroughly planned, MoE experiences it would be more than possible to cover key elements of information texts such as dictionaries, glossaries, leaflets, explanation and instructional texts, as well as recount, persuasion and argument text styles, and other types of information sources such as posters, maps and timelines. Children could access these documents as part of their investigations on behalf of their ‘Client’, a key role in the MoE experience. As part of their role as experts, the children could conclude their MoE experience by using the knowledge they have gathered during their research to compile their own information texts or sources to provide feedback to the ‘Client’. The drama element of the MoE experience is an opportunity for children to develop their social skills and to begin to think about the perspectives of other people. By developing specific roles children are able to explore scenarios, feelings and points of view that may be different from their own, in a safe and secure environment (Hymers, 2009, p.40). The discussion that is provoked through the role play experience allows for the development of a level of sophistication and vocabulary that the children may not normal have the opportunity or reason to use, and this can be carried over into their writing (McNaughton, 1997, pp. 55–86). Of particular interest to me, is the prospect that this approach could motivate and engage children in the lower ability groups. There is a growing body of research that appears to show that boys are not achieving at the same literary levels as their female counterparts (The National Literacy Trust, 2012, p.4). Although there does not appear to be a definitive reason why boys are underachieving in literacy, there are many influencing factors that could be considered, including gender identity and the lack of male role models, feminisation of the school experience and the types of curriculum texts that are made available. I would argue that although there appears to be a trend in boys underachieving, and that many of these factors are valid; we should not stereotype children’s ability by gender. There are of course many boys who would much prefer to read magazines, comics and other types of texts we rarely see in schools, but equally these could appeal to girls who are underachieving, and could have benefits to children who are within the parameters of ‘normal’ literary development. The idea that boys prefer to learn in a certain way could be linked to Garner’s theory of Multiple Intelligences (1983) or Fleming’s learning styles model (1987). The idea that children have a preferred way of learning that helps them retain information in a way that works best for them, or that they have some sort of innate speciality that we as teachers should recognise and provide for, has been gathering momentum for some time (Gordon-Győri and Fülöp, 2010, p.98). This is despite the fact that there is very little evidence to suggest that there is any scientific basis for these theories (Waterhouse, 2006, pp. 207-225). A proponent for these theories would argue that the MoE experience could draw upon a wide range of these learning styles or intelligences and could therefore support the learning of a broader range of children. I would argue that transmission teaching ultimately becomes boring for all involved 5 and that a good teacher will have, and use a wide repertoire of teaching techniques (Feiman-Nemser, 2001, p.1018) and, that if implemented effectively, this is bound to have a positive impact on the level of engagement and motivation of the pupils. Parallels can be drawn between the use of MoE and metacognition and selfregulation. To be successful in an MoE experience the children need to be able to self-regulate, manage their own motivation and engagement, set their own goals and monitor and reflect on their progress. The Education Endowment Fund (2014) highlights the benefits of these strategies, combined with collaborative learning, as having a significant impact on children’s development. The basis of these claims is extensive and comprehensive research, and therefore carries some weight. The MoE approach not only utilises elements of meta-cognition and self-regulation, but it also has a substantial element of collaborative learning, whereby the children and the teacher work together to define what needs to be learnt, how the learning can be done, and how best to present their findings (Cawthorn, Dawson and Ihorn, 2011, p.2). This involves a change in the power dynamic of the class room. The teacher is no longer the ‘transmitter’ of facts for the children to learn; they become the ‘enabler’, a role in which they can support the children whilst they direct their own learning. The power is shared with the children, not only by making the ‘experts’ in their field, but also by allowing them to collaboratively make decisions and influence the direction of their own learning, therefore creating a classroom with greater equality and giving the children more autonomy (Cawthorn, Dawson and Ihorn, 2011, p.4). Collaborative learning has a direct association with Vygotsky’s social constructivist theories, and his theory of the Zone of Proximal Development could be used effectively during a MoE experience, with the teacher providing opportunities for children to build upon their existing knowledge and skills, children will also be learning from each other during this time. Careful observation from the teacher will be needed to make assessments of children’s current knowledge and skills, steer the direction of future learning via the MoE and to plan methods for helping the children to move forward. By encouraging the children to make choices about how to investigate the issues surrounding the MoE, the teacher is supporting a form of inquiry learning, whereby children can use a variety of methods for gathering information. This could range from researching through books, using the internet and interviewing significant people to designing and performing experiments. Kuhlthau, Caspari, and Maniotes, (2007, p.9) suggest that there are five different types of learning that happen during the inquiry process, these include; curriculum content, information literacy, learning how to learn, literacy competence and social skills. Many of these could be used to support the children in developing their understanding of information texts, which can then be applied at a later stage in the MoE. 6 In conclusion I would maintain that the MoE, as part of the repertoire of a good teacher, could be used to support year two children to understand and apply the different aspects of information texts. The children are given the opportunity to become ‘experts’ within the context of the Mantle. They have a shared goal to socially construct their learning and gather information via mutually agreed methods. During this process, if they are provided with examples of information texts from which to research, they will develop their information literacy and literacy competence which they will then be able to apply to writing their own information texts. By providing a level of equality, promoting social and inquiry learning and using drama as a medium for extending the children’s thoughts and perspectives of the issues surrounding the Mantle, the teacher can stimulate a high level of motivation and engagement which in turns fosters children’s self-esteem, confidence and attainment. With careful planning and preparation, the Mantle can be made accessible to all ability groups, and evidence from an action research project undertaken by the Lancashire Literacy team in 2005, seems to support the stance that drama can have a positive impact on boy’s literacy. However, this is one example of a small scale research project. I have found that in general, the research base for the value and impact of MoE is limited but it appears to be expanding due to a growing interest in this approach to teaching. This assignment has given me some insight into the importance of having a wide repertoire of strategies to use within the class room to help maintain high levels of engagement and motivation. As someone who is not afraid to try something new, I look forward to the opportunity to put MoE into practice within my own teaching, but I also recognise that to do so effectively I would need the support and commitment of an inspirational and forward-thinking leadership team. Further training can be undertaken at flagship schools such as Bealings primary school in Suffolk, which I have enquired about, to further my understanding of this facet of teaching. I would also be interested in undertaking my own research project in this area to be able to see if positive impacts on writing ability are observed during and at the conclusion of a MoE experience. 7 References Alexander, R., (2013). Curriculum Freedom, Capacity and Leadership in the Primary School. (p.3). retrieved from http://www.robinalexander.org.uk/wpcontent/uploads/2012/04/Alexander-Nat-Coll-curric-capacity.pdf Arthur, J. (2012). Communitarianism. In J. Arthur & A. Peterson, The Routledge companion to education. (p.15). United Kingdom: Routledge. Beard, C., Wilson, J.P., Dr. (2006). Experiential Learning: A Best Practice Handbook for Educators and Trainers. (p.267). Kogan Page. Retrieved from http://www.myilibrary.com?ID=55062 Bolton, G. (2003). Dorothy Heathcote’s Story Biography of a Remarkable Drama Teacher. (p.177). Stoke-on-Trent: Trentham Books Ltd. Bee, H., & Boyd, D. (2009). Lifespan Development (5th ed.). Boston : Allyn and Bacon. Cawthorn, S., Dawson, K., & Ihorn, S. (2011). Activating Student Engagement Through Drama-Based Instruction. Journal for Learning through the Arts, 7(1). Retrieved from http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6qc4b7pt Department for Education. (2013). The National Curriculum in England Framework Document. (pp.28-30). Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/21096 9/NC_framework_document_-_FINAL.pdf Education Endowment Foundation (2014). Collaborative Learning. Retrieved from http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/toolkit/collaborative-learning/ Education Endowment Foundation (2014). Meta-Cognition and Self-Regulation. Retrieved from http://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/toolkit/meta-cognitiveand-self-regulation-strategies/ Education Portal. (2014). John Dewey on Education: Impact and Theory. Retrieved from http://www.education-portal.com/academy/lesson/john-dewey-on-educationimpact-theory.html#transcript Feiman-Nemser, S. (2001). From Preparation to Practice: Designing a Continuum to Strengthen and Sustain Teaching. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 1013–1055. doi: 10.1111/0161-4681.00141. Fraser, D., Aitken, V. and Whyte, B. (2013). Connecting Curriculum, Linking Learning. (p.36). Wellington: NZCER Press. 8 Gordon-Győri, J. and Fülöp, M. (2010) ‘Views of Intelligence’, in Arthur, J. and Davies, I. (eds). The Routledge Education Studies Textbook. United States: Routledge. Heathcote, D., Bolton, G. and O’Neill, C. (1995). Drama for Learning: Dorothy Heathcote’s Mantle of the Expert Approach to Education. 1st edn. Portmouth, NH: Heinemann. Hymers, J. (2009). ‘Little Children, ‘Big’ Questions’ Does Mantle of the Expert create an environment conducive to philosophical thinking in the Early Years? (BA (hons) dissertation). Retrieved from http://www.mantleoftheexpert.com/wpcontent/uploads/2009/05/julie-hymers-dissertation.pdf Kuhlthau, C. C., Caspari, A., & Maniotes, L. (2007). Guided Inquiry: Learning in the 21st Century School. United States: Libraries Unlimited Inc. Lancashire Literacy Team. (2005). Improving Boys’ Writing through Visual Literacy and Drama. Retrieved from http://www.lancsngfl.ac.uk/nationalstrategy/literacy/download/file/ReportImprovingBoysWriting.pdf MacBlain, S. (2014). How children learn. (p.21). United Kingdom: Sage Publications Ltd. McNaughton, M. J. (1997). Drama and Children’s Writing: a study of the influence of drama on the imaginative writing of primary school children. Research in Drama Education, 2(1), 55–86. doi:10.1080/1356978970020105 Ministry of Education. (2007). The New Zealand Curriculum. (pp.7,42). Wellington: Learning Media Limited Sprung, B., Froschl, M. and Gropper, N. (2010) Supporting Boys’ Learning: Strategies for Teacher Practice, Pre-K - Grade 3. (p.45). United States: Teachers’ College Press. The National Literacy Trust. (2012). Boys’ Reading Commission. (p.4). Retrieved from http://www.literacytrust.org.uk/assets/0001/4056/Boys_Commission_Report.pdf Waterhouse, L. (2006). Multiple Intelligences, the Mozart Effect, and Emotional Intelligence: A Critical Review. Educational Psychologist, 41(4), 207–225. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep4104_1 9