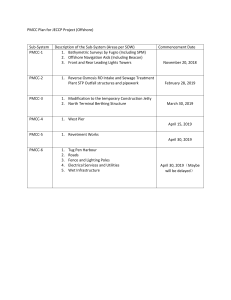

The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect The Journal of Academic Librarianship journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jacalib Undergraduate students' experiences of using information at the career fair: A phenomenographic study conducted by the libraries and career center T Ilana Stonebraker , Clarence Maybee, Jessica Chapman ⁎ Purdue University, United States of America ABSTRACT Information literacy is vital to students seeking employment following their undergraduate education. Yet little is known about how students approach using information as part of their career search. This phenomenographic study examined how students experience using information as part of a career fair, or on-campus job expo. Researchers interviewed undergraduate students after a major campus career fair. The findings suggest that students may experience using information in a career fair context as: 1) navigators completing a series of steps, 2) performers seeking to connect with the right person, or 3) aligners determining if a company is a match for them. Introduction Literature review Career fairs, also referred to as job fairs or career expos, are events where companies send recruiters to showcase their firm to potential employees. Job seekers strive to make a good impression to potential employers by speaking face-to-face, asking questions, and filling out applications. On college campuses, career fairs are often targeted at entry level positions. Most large universities host at least one, and sometimes several career fairs annually. Purdue hosts over 30 career fairs each year (“Purdue CCO - Employers: Career Fairs,” n.d.). These career fairs may be focused on a single population (such as international students) or a disciplinary or professional area (such as The School of Management Employers Forum). Career fairs are very important to students because they provide opportunities to secure highly sought after internships as well as permanent employment. Searching for a job is a complex task that typically involves a variety of activities, which include using informal and formal information sources (Saks, 2006). This research investigates student experiences of using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair. The findings suggest that students may experience using information in the career fair context as: 1) navigators completing a series of steps, 2) performers seeking to connect with the right person, or 3) aligners determining if a company is a match for them. The findings suggest new pedagogic strategies for expanding student awareness of aspects of using information to support their goals related to career fair participation. Career fairs are very important to universities as they may lead to increases in the number of students employed after graduation, which may affect university rankings. With an ever-increasing number of educational options, potential students are increasingly more interested placement rates as well. In addition, career fairs reinforce university relationships with alumni. Employers value career fairs because they strengthen their relationship with the university and provide access to a pool of potential new employees. Research has shown students are greatly impacted by personal interactions with companies, and the companies that they interact with at a career fair are most likely going to be the companies to which the students choose to apply (Sciarini & Woods, 1997). Given the role that information plays in the job search (Saks, 2006), academic libraries may find opportunities to support students, the institution, and employers by working to bolster students' ability to use information effectively. To meet the needs of students preparing for and participating in a career fair, libraries may partner with their campus career center. Librarians at Purdue University have worked with eight career units to create a tailored resource for career information (Dugan, Bergstrom, & Doan, 2009; Hollister, 2005). In addition, as part of a campus collaboration, libraries have further developed educational resources beyond single portals as part of successful career center collaborations (Howard, 2017; Pun, 2017; Sheley, 2014). At University of Buffalo Libraries, collaborations with campus career centers have re- ⁎ Corresponding author. E-mail address: stonebraker@purdue.edu (I. Stonebraker). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2019.05.002 Received 29 January 2019; Received in revised form 3 May 2019; Accepted 3 May 2019 Available online 14 May 2019 0099-1333/ © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. sulted in ongoing efforts to improve library collections, services, facilities, and web presence (Hollister, 2005). in higher education experience information literacy. Understanding learners varied experiences can enable teachers to design instruction aimed at helping learners to experience the phenomenon being studied in the classroom in new and more complex ways (Marton & Tsui, 2004). Experiences of the career fair Building on past efforts, further development of educational resources by academic libraries to support students' job searches can be informed by better understanding the first-hand experiences of students as they prepare and participate in career fairs. To date there have only been a small number of studies that have examined students' perceptions of career fairs. Such studies have primarily focused on students' perceptions of the usefulness of attending a career fair, or satisfaction related to attending one. For example, Roehing and Cavanaugh (2000) surveyed students about their perceptions of interactions with recruiters at career fairs, determining that students appreciate recruiters who dressed professionally, show genuine interest in them, and have brochures and other handouts to take away. Payne and Sumter (2005) administered a survey to determine what students liked and felt they gained from participation in a career fair. The findings suggest that students felt that the career fair exposed them to information about careers, provided information about the hiring process, and enabled them to make internship or future career contacts. A study of students who attended a career fair with hospitality industry employers found that the top three reasons students attend the fair are: 1) networking, 2) learning about companies in the field, and 3) the potential for arranging internships or interviews for permanent positions (Silkes, Adler, & Phillips, 2010). Developing a survey from the research conducted by Roehing and Cavanaugh (2000) and Payne and Sumter (2005), Milman and Whitney (2014) also studied students who attended a career fair for the hospitality industry. However, in this case the study focused on factors associated with students' satisfaction of the fair. The findings indicate that students' perception that the fair had enough industry representatives from their specific areas of interest and that the companies in those areas had open positions available supported their feelings of satisfaction. Satisfaction was also associated with perceptions of whether or not a recruiter's actions indicated an interest in them, such as taking their resume. The current literature focuses on larger perspectives of job searching (such as job fit) or narrowly focused on career fair satisfaction in order to show success of a given career fair. Yet given how important it is for undergraduate students to find their first job, knowing how students use, or don't use, information when preparing, and participating in the career fair is crucial for designing instructional activities to support their career search. Although not specifically focused on career fairs, phenomenography has been used to explore student experiences of using information to learn in educational settings (e.g., Edwards, 2006; Lupton, 2008; Maybee, 2006; Maybee, Bruce, Lupton, & Rebmann, 2017). The current research uses phenomenography to identify students' first-hand experiences of using information when participating in a career fair. Participants Once our research plan was approved by our institutional review board (IRB), we began the study. Phenomenographic research uses “purposive sampling,” in which students were invited to participate specifically because of their ability to provide data that would inform the research question (Patton, 1990, p. 46). The purpose of phenomenography is to reveal or ‘uncover’ experiences of a phenomenon. As long as the participants have experience of the phenomenon, in this case using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair, the number of participants may be relatively small. In contrast to other research methodologies that aim to identify trends, each experience revealed in a phenomenographic study, even if only held by one person, is an important finding. One of the researchers, whose position involved providing career support to students, invited students to participate in the study. The seven participants interviewed were seniors in the School of Management. All of the participants had previously attended one or more career fairs during their undergraduate career, and several had volunteered with the School of Management Employers Forum (SMEF), a campus organization that hosts career-related events and a career fair in order to connect students with internships and career opportunities. Four of the participants were male, three were female, and all were between the ages of 18 and 24 years old. This study was conducted directly after a major career fair. Within the previous week of being interviewed, each participant had attended this career fair on campus, but had yet to accept a position with a company. Data collection and analysis The seven interviews were conducted in a library conference room, which provided a convenient, neutral space. The interviews, which were audio-recorded, were typically 30 min in length, with the longest taking 50 min to complete. When students arrived for the interview, each one was asked to read over an information sheet about the study that described our efforts to preserve anonymity, and they were apprised that they could end the participation in the study at any time. The interviews followed a semi-structured interview protocol, which is the most common method of collecting data in phenomenographic research. Emphasizing a second-order perspective, a specific type of open-ended questions are used (Marton, 1986), which guide the interviewee to “thematize” aspects of their experience about the phenomenon under investigation (Bruce, 1994). A phenomenographer would ask, “What is your experience of information literacy?” not “What is information literacy?” Initial prompts are followed up with clarifying questions, such as, “Can you tell me more?” Or “Why is that important?” that are intended to get participants to expand on their original answers (Bowden, 2000, pp. 9–10). “Bracketing” techniques are applied in phenomenographic interviewing, meaning that the researcher takes steps not to impose any presuppositions on the participant during the interview (Åkerlind, 2005, p. 108). In our study, five primary interview prompts were used during the interviews with the student participants: Methodology The research question guiding our study is, “How do students experience using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair?” Phenomenography, a methodology developed in the 1970s in Sweden by a group of educational researchers, was selected for this study because it would allow us to understand students' firsthand experiences of using information for the career fair. Rather than using theories to explain the data they collected (first-order perspective), phenomenographers adopt a second-order perspective that aims to “reveal” different experiences of a phenomenon (Marton, 1986). Phenomenography holds that there are a limited number of qualitatively different ways that people in the same context experience the same phenomenon (Marton, 1994). For example, Bruce's (1997) seminal phenomenographic study revealed seven different ways that educators • Tell me about your experience of the career fair. • How did you use information to prepare for the career fair? • How did you use information when participating in the career fair? • Describe your view of someone who uses information well when preparing for, participating in, and following up on the career fair. • Is there anything else would you share about your experience of using information for the career fair? 359 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. The transcriptions of the recorded interviews were then analyzed. In a phenomenographic study, the outcome is an identification of categories, which describe key aspects of the qualitatively different ways in which the phenomenon being researched is experienced (Marton & Booth, 1997). The categories are not necessarily attributed to individuals, but instead may represent an aggregation of the experiences of multiple individuals. Following phenomenographic protocols, the researchers read though the interviews transcripts a number of times to become familiar with them and then identified key aspects that defined the formation of the categories. Each category is comprised of two aspects: 1) referential, and 2) structural (Marton & Booth, 1997). Referential aspects refer to the different meanings. Structural aspects indicate what someone experiencing the phenomenon in this way is: 1) primarily focused on, 2) in the background of their awareness, and 3) in the periphery or margins of their awareness. Described in detail in the following section, the analysis resulted in three categories depicting how students experienced using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair. The categories of description are arranged into an outcome space reflecting how the categories are structurally related. The categories of description and the outcome space represent the collective experience as analyzed and described by the researcher. Fig. 1. Structure of awareness for category 1. focus is step completion. In the background, these students are aware of the need to prepare for the career fair. These students experience using information as conducting research on companies and positions so they have something to show that they are prepared. Below is an example from John, one of the students interviewed in the study. Results The analysis of the interview transcripts revealed three categories outlining the varied ways that the students experience using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair: So, we always tell people you know, you need to do your research for the company. You need to know what the position offers … if you read general basics of what the company is what their recruiting for … those are the two steps that you really need to do above all anything else. 1. Navigator – Completes a series of steps, part of which involve using information. 2. Performer – Prepares to engage with a recruiter that may connect them with the ‘right’ person. 3. Aligner – Determines if a company is a match for them personally. These students often assume that jobseekers are looking to show a recruiter that they have the right credentials to fill a position. When they present information, they see what they are doing as following a defined process to display knowledge of the company. Another example from the same subject: Each category is described in more detail below, including its referential and structural aspects. The referential aspect conveys the meaning of the category, while the structural aspect communicates different layers of awareness (Marton & Booth, 1997). These layers identify what is central to each category (i.e., its focus); elements that are in the background and provide contextual understanding or enable the category focus to be discerned; and elements of awareness that are peripheral (i.e., the margin). Using pseudonyms to protect participant anonymity, quotes from the interviews are included to exemplify the structural aspects. Categories may also include dimensions of variation, which are recognizable themes or common threads that traverse each category of description. When a dimension of variation appears in each category, its character will differ from one category to another (Åkerlind, 2005). As shown in Table 1, two dimensions are identified in the study that focus on what is considered information and what is considered research in each of the three categories. An outcome space describing how the categories relate to one another concludes the results section. So I used it for Center, this was literally yesterday. And I looked up the night before it was about their work and solving a problem for coal miners, what Center did and the details are gone out of my brain now. But it was basically they were hired to help them solve a very general basic problem of like you know, tableting. It was something to do about the workers schedule or some sort. It was very complicated… not my field of expertise. But then I brought it up back when I gave my pitch: […] ‘you know, when I was doing my research I really applaud Center's work … what you guys did for the coal mining.’ And she, the recruiter didn't even ask me more to follow up with that. But I think they liked that I even did that. I think you know, that stimulated the conversation further, so I wouldn't be just another resume in the pile, and didn't ask me to leave or anything. Because the Navigators experience using information as a step in a process, they are very concerned when people do not follow the steps required and are still successful: Category 1: Navigator So, for practice I was showing two underclassman that I had to show around the career fair. I went up to a company who I had no… I knew what they did, but I had no idea what their position was, who Navigators experience using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair as part of a series of steps. Outlined in Fig. 1, their Table 1 Dimensions of using information for the career fair Navigator Performer Aligner Information is… Company information Research is… A preparatory step Company information News about the company Finding information to connect with a recruiter Company information Information about one's self Finding information that helps determine company fit 360 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. Dilly that everyone just can't escape from. […] And so with you as an individual trying to get a job or an internship, you need to be quick to the point and be memorable. And I think that's how I would view the interaction between a recruiter and a student. Persuasion is what differentiates their approach from the Navigators. Navigators are interested in assessing and completing the right steps. For Performers, the steps are less defined and if you perform well, the steps are not needed. An example of how Performers see information from Tom: So what I realized much later on is that it's okay. You can go in with a 2.4. Go in and talk to them. Of course I don't say you should get a 2.4, but, study hard! But I would say, go into the fair, talk to them. Be confident. It's not something that you can develop over time, develop instantaneously, it comes over time once you have more experience. It took years for me. I would say I was only more comfortable with it by the end of junior year. And that's late. Fig. 2. Structure of awareness for category 2. As with Navigators, making a career decision is on the margins of students who experienced using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair as described in the Performance category. Also similar to the Navigator category, the dimension of information in the Performer category is company information, but also includes news items about the company, such as current events or growth projections, etc. (see Table 1). In the Performer category, the dimension of ‘research’ is experienced as finding information that aids the student in making a connection with a recruiter. they were recruiting for, whatever. I just did it for the undergraduates to see me practice and elevator pitch or talking to them. And it went fine. It was weirdly okay. Like they told me to contact them if I you know wanted to apply for the job and what not. On the margin for these students was making a decision about a company with which to pursue employment. Students who are Navigators aren't looking for the information to change which companies to talk to or whether to continue to talk to the company. They see information use as part of the preparation for other career fair steps. The dimensions of this category described in Table 1 indicate that the information students engage with is company information, while research is experienced as one of the steps that students complete to prepare for a career fair. Category 3: Aligner Aligners experience using information to prepare for and participate in the career fair as part of determining if the company is a match for them personally. As outlined in Fig. 3, the main focus in this category is on using information to determine ‘company fit.’ On the margins in the Navigator and Performer categories, making a career decision is part of determining company fit, and therefore, a focus of the Aligner category. In the background of these students' awareness is a focus on a company's culture and other attributes, and how those elements relate their own personal interests. Aligners may follow similar steps to those described in the Navigator category, but in the Aligner experience the steps are focused on finding a company that matches one's personal or professional interests. For some of these participants, the interests reflect their expectations or hopes for their career. For example, one participant (Jasmin) volunteered in the community, so a company having a strong corporate social responsibility was important to her: Category 2: Performer Performers experience using information to prepare for and participate in a career fair as a form of performance. They believe that the short presentation they give at a career fair must allow the recruiter to recognize that they are the right person for a position. Fig. 2 outlines the structure of awareness for the category. The focus is on getting in front of the right person. Their intent is to persuade using information. In the background of the awareness of the students who experience using information to prepare for, and participate in the career fair in this way is ‘networking’ with a recruiter or other important contacts. One student described how he sought out a recruiter he had met previously to keep his connection with her. Also in the background for students with this experience is conducting research that will aid with their performance. As an example, one participant (Caleb) saw researching to prepare for a career fair as putting together a commercial: I did grow up volunteering at an assisted living at home in the Indy area, so that was always important and then my high school was like a Catholic high school and we had to do service hours, that's just something that is really important and maybe it's like the way my So I guess you only have so much time. It's a balance of you want to get as much information across about you, your interest. You also want to learn as much as you can about the company. What they have to offer, the positions they're looking for, the types of people they're looking for, any requirements you may or may not meet. And you don't have time … like an infomercial, right. An infomercial's long … it's fifteen, thirty minutes. And it's repeating the same facts over and over and over. Where a commercial is thirty seconds, twenty seconds. It's a spotlight, its showcasing high priority information that needs to get across to the viewer. Whereas when I'm handing over my resume, I want to highlight big things quickly and efficiently to get the information across. Without taking up too much of their time, cause there are people behind me, or there's a line and a queue of people coming. But also being memorable, right? So in a commercial, the best commercials, marketing wise, are the ones … the jingles, right? The Peyton Manning jingle that everyone can't get out of his head for Nationwide, or the new Budlight Dilly Fig. 3. Structure of awareness for category 3. 361 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. to students, but often created a barrier where students were not using information they learned in career fair settings since they often would focus on fast-fact type questions. As her practice improved, the librarian created a second version of the worksheet that included an actionable list of tasks in research stages and a set of “mad-libs” or sample questions and answers to show how students could use information in career fair settings (see Appendix A). As you can see from the story, originally the librarian's practice was really only suiting Navigators, but in their practice had started to also teach in ways that supported Performers and the way they use information. The librarian's practice had always centered on the assumption that students “knew what they were looking for” and that was why they were interested in talking to companies. It turns out that students often had not taken the time to align their values with the task at hand, and were often using the search process as a means of self-reflection. To use a metaphor, students were going to a clothing store and trying on every pair of shoes in the store, often starting at the most expensive shoe, versus deciding before they started what type of shoe might be best. This is certainly one way to find shoes, but it does take quite a bit longer and arguably makes the task harder. With the information gleaned from this study, the librarian has now changed the handout and starts with a list of questions about what they were looking for and what was important to them (see Appendix B). At the same time, a given student also considers questions on what is important to the company, such as where they are headed, what they value, etc. Then students can draw lines from elements of what they are looking for with a potential company, thereby suiting the type of learning experience observed in the Aligners theme. This worksheet was piloted in the fall and while not all students feel the need to align, those who do seem to feel a great sense of relief at having some time to consider the options. It appears to eliminate some of the anxiety with starting the research process. The career fair advisor teaches a required course on career readiness, which includes career fair preparation. The career advisor saw the results of the study as a reaffirmation of some of the more reflective elements of the class, such as looking at fit and personality. The career advisor saw abundant utility in turning the study around and teaching the students about the three categories as a tool of reflection in how they find information, as well as how they interact with recruiters in the career fair environment. In addition, the study made the career advisor have many questions about transfer, or how students would be able to use skills gained from the class in career fair environments, and was interested in better understanding longitudinally which of the skills taught in the sophomore class were being best retained over time. Mom raised me, it's like I just feel so blessed in my life I want to give back and I definitely want to give back to a company that does that, so that's really important, and then like on my resume now I'm involved in a club I'm chair community service and like college mentor so that's just like I think one of my key values I look for, how maybe I've been raised and then Stryker did a lot with that so when I looked at, that was one of their main things. Students experiencing using information to prepare for, and participate in, a career fair as described in the Aligner category do not only determine ‘fit’ based on social aspects, but other factors may be important as well, such as company viability. For example, another participant had worked at an internship where the company was not doing very well financially and was likely to go bankrupt in the next couple of years. This participant was interested in looking for companies that he felt would be successful and stable over the next couple of years. These students are also engaged in a larger internal process where they are assessing their own personal interests and how they fit a company culture. Students in the Aligner category were less focused on networking. Unlike Navigators or Performers, meeting the ‘right’ people is not an end within itself. Aligners then ask those people questions to ensure that company is indeed a good fit for them. As shown in Table 1, the dimension of information in the Aligner category is company information—the same as with the other two categories. However, information about one's self is also part of this experience. Comparing the two types of information informs the students' choices regarding companies with which to pursue employment. In the Aligner category, the dimension of ‘research’ is experienced as finding information that helps determine company fit. Outcome space The examination of the structural elements reveals that the Aligner category has more complexity than the two other categories. That is to say, the experience described in the Aligner category includes aspects that are also part of the other two categories, such as an awareness on preparation as outlined in the Navigator category, and networking that is part of the experience described in the Performing category. However, the Aligner category includes another aspect that is in the margins of the Navigator and Performer categories: making a career decision. While the experiences described in all three categories were engaging in research activities, the Aligner category involves research aimed at making a career decision by learning about a company of interest, as well as knowing information about one's own personal or professional interests. Discussion Applications for practice After their experience at the career fair, students may participate in multiple screening interviews, networking events, and sometimes even portfolio show and tells or assignments. Further, a person's career trajectory extends beyond their first position as they strive towards their ultimate career goals over the continuing decades. This study looks at a single first step in a lifetime process that a job seeker must undertake. More research is needed to understand the experiences inside of the larger career search process. While we know quite a bit from the literature about what might make someone successful in their job search, we know less about the experiences they have. Of course, all studies have limitations. The phenomenographic method is used to explore experiences related to the use of information. Further studies are needed to determine how to best speak to each these career information experiences in context. Further studies may want to measure how teaching towards Aligners may improve career fair success. More studies are also needed to see if these three experiences are found in the larger study population, or in the workplace at large. Included on the research team for this study was the Assistant Director of the career center and librarians. The implications of the study are both for librarians helping students prepare for the career fair as well as career advisors who also help students prepare for career fairs. The results both confirmed previous practices of each (Kirker & Stonebraker, 2019; Stonebraker & Howard, 2017; Stonebraker & Fundator, 2016), but also suggested new ways to support student learning. One member of the research team was a business librarian who, in the weeks before the career fair, taught 300–700 students in a number of one-time lectures and consultations. Originally the librarian gave out a worksheet of company questions to orient students to the type of information needed. Students need to know how to research companies to find out information about products, opportunities, etc. The librarian covers a set of databases based on what stage of the research process students occupy (see Appendix A). The librarian found this was useful 362 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. Conclusion recruiters. Career fairs present a high stress time in a students' transition to adulthood. As professionals, we may look back upon our own transition to adulthood and forget many experiences and aspects. Students must take their lessons from their education to reflect upon the type of worker they would be in the workforce. In order to help students best make this transition, universities must understand their learning and information literacy experiences. This study used a qualitative, phenomenographic method to investigate how students experience information in career fair environments. From this work, we found three main themes. Aligners describe a series of experiences where the student relates company information to who they are a person. Navigators look at information about companies as a path towards actionable steps. And Performers look to company information to give them clues about how best impress Appendix A. Library handout before study 363 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. 364 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. Appendix B. Library handout after study 365 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. Pergamon. Marton, F., & Booth, S. (1997). Learning and awareness. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. Marton, F., & Tsui, A. (2004). Classroom discourse and the space of learning. Mahwah, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates. Maybee, C. (2006). Undergraduate perceptions of information use: The basis for creating user-centered student information literacy instruction. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 32(1), 79–85. Maybee, C., Bruce, C. S., Lupton, M., & Rebmann, K. (2017). Designing rich information experiences to shape learning outcomes. Studies in Higher Education, 42(12), 2373–2388. Milman, A., & Whitney, P. A. (2014). Evaluating students' experience and satisfaction at a hospitality and tourism college career fair. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 13(2), 173–189. Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Payne, B. K., & Sumter, M. (2005). College students' perceptions about career fairs: What they like, what they gain, and what they want to see. College Student Journal, 39(2), 269–276. Pun, R. (2017). Identifying partnerships for career success: Academic collaborations between librarians and career centers. 2017 SLA conference. Roehing, M. V., & Cavanaugh, M. A. (2000). Student expectations of employers at job fairs. Journal of Career Planning & Employment, 60(4), 48–52. Saks, A. M. (2006). Multiple predictors and criteria of job search success. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(3), 400–415. Sciarini, M. P., & Woods, R. H. (1997). Selecting that first job: How students develop perceptions about potential employers. Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly, 38(4), 76–81. References Åkerlind, G. S. (2005). Variation and commonality in phenomenographic research methods. Higher Education Research and Development, 24(4), 321–334. Bowden, J. A. (2000). The nature of phenomenographic research. In J. A. Bowden, & E. Walsh (Eds.). Phenomenography (pp. 1–18). Melbourne: RMIT University Press. Bruce, C. S. (1994). Reflections on the experience of the phenomenographic interview. In R. Ballantyne, & C. S. Bruce (Eds.). Phenomenography: Philosophy and practice (proceedings) (pp. 57–70). Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology. Bruce, C. S. (1997). The seven faces of information literacy. Adelaide: Auslib Press. Dugan, M., Bergstrom, G., & Doan, T. (2009). Campus career collaboration: “Do the research. Land the job.”. College & Undergraduate Libraries, 16(2–3), 122–137. Edwards, S. L. (2006). Panning for gold: Information literacy and the net lenses model. Adelaide, AUS: Auslib Press. Hollister, C. (2005). Bringing information literacy to career services. Reference Services Review, 33(1), 104–111. Howard, H. (2017). Landing the job: How special libraries can support career research. Public Services Quarterly, 13(1), 55–59. Kirker, M. J., & Stonebraker, I. (2019). Architects, renovators, builders, and fragmenters: A model for first year students’ self-perceptions and perceptions of information literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 45(1), 1–8. Lupton, M. (2008). Information literacy and learning. Blackwood, S. Aust.: Auslib Press. Marton, F. (1986). Phenomenography: A research approach to investigating different understandings of reality. Journal of Thought, 21(2), 28–49. Marton, F. (1994). Phenomenography. In T. Husén, & T. N. Postlethwaite (Eds.). International encyclopedia of education (pp. 4424–4429). Oxford and New York: 366 The Journal of Academic Librarianship 45 (2019) 358–367 I. Stonebraker, et al. Sheley, C. (2014). Get hired! Academic library outreach for student job seekers. Indiana Libraries, 33(2), 71–72. Silkes, C., Adler, H., & Phillips, P. S. (2010). Hospitality career fairs: Student perceptions of value and usefulness. Journal of Human Resources in Hospitality & Tourism, 9(2), 117–130. Stonebraker, I., & Howard, H. A. (2017). Evidence-based decision-making: Awareness, process and practice in the management classroom. Journal of Academic Librarianship. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acalib.2017.09.017. Stonebraker, I. R., & Fundator, R. (2016). Use it or lose it? A longitudinal performance assessment of undergraduate business students’ information literacy. The Journal of Academic Librarianship. 367