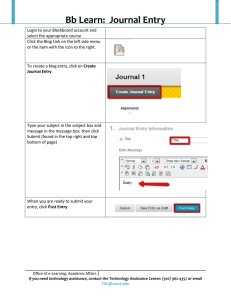

Senior Fellow HEA 2014 (case studies) These documents form my application for a Senior Fellowship of the Higher Education Academy. PART 1: Reflective Account of Practice With over a decade of HE teaching, including 6 years of programme leadership experience, I currently lecture on BA(Hons) Graphic Design for Digital Media at GCU. Before beginning my teaching career I had obtained both a HND and Honours degree. During my career I actively pursued professional development obtaining a Masters Degree and two teaching qualifications: a Certificate in Education (Post 16) and a C&G 7307. I am due to complete a PhD in Visual Communication from Edinburgh College of Art early in 2015. Recently I completed my training as a PhD supervisor in preparation to supervise PhD design students as soon as I have the opportunity to do so. I already have 4 years of Honours supervision at GCU, and three years as Research contextual review supervisor. My personal teaching focus is on placing the design skills the students learn into a broader cultural context through applied and academic research to strengthen their creative concepts. I contextualise this in the design studio supported through a mixture of lecture, seminar, crits, practical design work and presentations. Previously at St Helens College I had over 6 years experience in programme administration, team leadership and coordination. Here my responsibilities included: student enrolment, induction, retention, pastoral care, assessment and programme evaluation. In this role I further developed strategic external links with Sony Computer Entertainment Europe, implementing a dayrelease pathway and night classes for them on my degree, increasing departmental revenue. As an early career researcher I am already REF 2014 ready with published academic papers on Visual Communication (Wood, 2009c; 2010; 2011) and I have presented at international design conferences in Rome, Seoul and in the UK. I am also the author of three design books (Wood, 2009a; 2009b; 2013). In 2011 one paper delivered at conference resulted in an invitation to join pragmatist Professor Richard Shusterman’s Somaesthetics international research group, and another paper led to the book commission from Bloomsbury. In 2008, with funding from Liverpool Biennial 2008, I project managed the BiennielFreerunner school community project. This 6 month project commissioned by De La Salle High School brought students and graduates with skills in graphic design, animation, video, web design and screen-based design together to make a short CG/live action film. Traceur Tag was premiered privately to an invited audience before a public launch as part of Liverpool Biennial 08 Schools Project exhibition The Future, Fiction and Fantasy. This project was documented on the project blog (biennialFreerunner, 2008) and in an exegesis (Wood and Krakiewicz, 2008). At GCU I organise an annual 2nd year student study trip to London to visit graphic design agencies working in the print and digital sector. From these visits I am engaged in negotiating an internship with a digital agency for final year/graduate students that is on going. I have strategic experience of being both an External Examiner and a validation panel External Advisor. I have just completed a 5-year tenure for Staffordshire University’s Graphics and Digital Design, and Digital Media Production Foundation Degrees. My responsibility was for ensuring the comparative quality of provision across 3 colleges and 4 programme leaders. I am now External Examiner for the next 3-4 years for Leeds Metropolitan University’s Web Design, Games Design, and Animation & Illustration Foundation Degrees I now have responsibility for ensuring the comparative quality of provision across 2 colleges and 3 programme leaders. I have been an External Advisor to 2 different validations in 2012. I was the initial advisor for Liverpool John Moores University’s re-validation of their BA(Hons) Digital Media Design, and full External Advisor for University of Chester’s validation of BA(Hons) Graphic Design and BA(Hons) Game Art. At GCU I have conceived and written the module Design Culture 3: Research to improve design students’ scholarship and research activities. This has improved a design subject research culture and the design students’ intellectual creative practice. I have been a 3rd year tutor for 2 years and act as a point of contact for students with issues where it isn’t module or programme specific. This involves pastoral care for students who are struggling academically and/or personally. In this role I have contributed to the retention and improvement of students (especially articulating direct-entry students) by agreeing individual action plans. I currently lead three undergraduate modules and I teach on a further three modules. I am currently evaluating and revising the one module to consolidate students’ graphic design skills around User Experience (UX) for a variety of digital media outcomes. This will be delivered next semester. While at St Helens College I conceived, wrote and led a programme development team for two new undergraduate degrees to successful validation. I ran one of these degrees BA(Hons) Entertainment Media Design as Programme Leader. It built upon a solid regional engagement with Sony Computer Entertainment after previous enterprise and development activities with them. PART 2: Case Study One THIRD YEAR RESEARCH MODULE DELIVERY: Blended Learning for Students on Exchange The new module Design Culture 3: Research was written and validated in my first academic year at GCU (2009-10), and then delivered for the first time in Trimester B of academic year 2010-11. Each year since has seen the delivery of the teaching and the support of the students develop according to the needs of the students. In the first year (2010-11) I supervised both product and graphics students totalling about fifty students, with one student studying abroad. In the next year (2011-12) the 3D students were added to the module. Altogether this raised the number of students to about sixty, with three students studying it from abroad. In the last academic year (2012-13) there were eightyfive students, with nine students studying the module remotely. This case study will discuss the blended learning that I developed and implemented to ensure students could effectively study abroad. It will evidence how I used blended learning to develop independent and collaborative learning in my students, adapted from a Flex Model of blended learning using “an individually customised, fluid schedule among learning modalities” (Staker and Horn, 2012, pp12-13). The module itself had not been written for delivery as distance learning as this was not a factor at the time of validation. But through innovations in the application of my Core Knowledge and Professional Values I managed to quickly implement a structure from within the validated modular framework. This included Skype tutorials, email correspondence, lecture slides converted into voiced-over lecture movies, and extra resources available through the Virtual Learning Environment (VLE) Blackboard platform and Dropbox file-sharing digital technology. These learning modalities were customised to suit the individual learning needs of those students who needed to study away from class. The Module The module itself is a third year module within a four-year Honours degree. I was encouraged to write the module by the department head who knew I had written and delivered similar modules previously (see case study 2). It was to fit into the cultural strand within the established curriculum of BA(Hons) Graphic Design for Digital Media, but it would also be delivered across other programmes within GCU’s creative framework. The module would focus on raising students’ academic skills within their own design discipline. The module itself was 20 credits and had six learning outcomes: LO1. Define the cultural context of your own design practice LO2. Identify and utilise existing research methodologies and apply them to your own practice LO3. Analyse and critically evaluate information, and reference sources using the relevant academic conventions LO4. Distinguish between popular and scholarly materials LO5. Synthesise and distil a complex piece of personal research LO6. Articulate and disseminate your research in an academic context These outcomes directly placed academic research within the strand of design culture and the mode of study within student-centred active learning. Each student would propose what they wanted to understand more within their own design specialism that would benefit their specialist design development at Honours year (and beyond). This meant that each student would take ownership on becoming more expert in a specific area of their chosen design field [LO1]. Therefore my role as module leader would be as a supervisor of the students’ own progress through their own research. In this role I would only advise and supervise how each student a) diagnosed the current gaps in their learning, b) formulated their own objectives, selected and organised content they identified as relevant from their research, and then c) determined what they understood from this content in relation to a research question they shaped themselves. In doing c) students evaluated each piece of relevant research, annotating it with their own critical thoughts [LO3]. This structure was an innovation on the Taba Course Development Model (Oliva, 1992, p. 160-2) for curriculum development, and structured so that each student could design their own micro-curriculum that fitted their developing needs. To begin this process I introduced the students to researching academically. I taught them the differences between popular sources of information and scholarly sources of knowledge through a mix of lecture supported by practical exercises and seminar demonstration [LO4]. In much the same way I introduced secondary researching techniques such as searching and locating sources, reading critically, and evaluating relevant and legitimate sources [LO2]. The student would use another innovation I introduced to collate and evidence how the collected and processed each piece of research. This was a research diary pro forma comprising of a 5-column Word document (Fig.1) in which they could record in Harvard reference source information, the research itself, their critical annotation and judgement on it’s scholarly strength [LO5]. I had successfully used this diary pro forma at my previous institution. From this rigorous process that took the students two thirds of the twelve-week research project, they would then write a 2,500 word contextual review of their accumulated research based around their question [LO6]. As this was most students first attempt at writing academically (rather than just an essay or a report), my role as supervisor was supplemented by GCU’s Learning Development Centre. The Students The students who took this module were all design students but the interpretation of ‘design’ was quite broad. Three quarters of the students were not from my direct graphics specialism. I anticipated this when writing the module and accommodated it within the module’s emphasis on student-centred learning. I did have a personal interest in other design specialisms and have been an advocate of the multi-disciplinary design company IDEO’s ethos of the T-Shaped Designer. Juho Parviainen an IDEO designer explains that you need “a deep knowledge of your expertise area [the vertical of a T] (…) but also a broad understanding of many different disciplines [the horizontal bar of a T]” (SuarezGolborne, 2007). Within the research module all students (those in class and those abroad) are beginning their first step in what Susan Nicholls calls the “field of knowledge production” (Kamler and Thomson, 2006, p45). As such they need both the guidance and the space to pursue the literature in their design field, focused around the research question that they devise. Design Culture 3: Research would prepare all the design students the ability to expand their specialist knowledge [the vertical of a T] and also become more knowledgeable about other related disciplines, theories and practices (e.g philosophy, psychology, sociology) outside their specialism that had a bearing on their research question [the horizontal bar of a T]. It was from my own T-shaped experience and knowledge that I was able to guide the students through their own T-shaped development. In class on a weekly basis this was easier to supervise face-to-face through group seminars and personal tutorials. But for those students studying abroad it was more problematic. While all students enrolled on the module had access to resources to help them with their research on GCU Learn (Blackboard), this VLE was not fully suitable in this case to support those students who were not in class. On GCU Learn all lecture slides were archived after each lecture was delivered. These slides contained online links to further resources that students would need to use. Also slides from workshops were added, plus the digital templates they would need for starting a research diary. Examples of good contextual reviews and diaries from the previous academic year were also archived. But these files needed the students to have attended class or a lecture in order for each student to make the most of them. Some of the students studying abroad found in some cases their university email was not working, meaning they could not access Blackboard. This technical infrastructural issue can quickly get sorted if in university but became more time-consuming when in another country. Therefore I decided that additional support was needed for those students who could not attend class. This did predominantly mean those nine students who were abroad, but it also included students who missed class due to special factors (such as family illness and death, and work-related issues). The Blended Learning In the first two years I was the sole lecturer on the delivery of the module, but by 2013 I led a small team of three: myself as module leader, one additional lecturer to supervise the delivery to the product design students, and one lecturer to deliver one session on ethical research. The additional supervising lecturer enabled me to concentrate the graphic, animation and game art students, and those students who were abroad. These latter students benefited from blended learning that was bespoke to their contextual needs. Macdonald and Creanor in their book Learning with Online and Mobile Technologies: A Student Survival Guide (2010) stress, “communication technologies can also bridge divides by allowing contact between fellow students regardless of geography, disability or family responsibilities” (pp3-4). Therefore to ensure that those students not in class could all access further academic support 24/7 I set up a Dropbox folder (GCU Design Research) that I could control access to. Dropbox.com provides a free server-based file sharing service with the ability to have localised folders on each sharer’s hard drive mirroring what is on the server. This meant that a file could be uploaded locally on one hard drive and Dropbox will automatically download it to each shared folder, so that the next time students started their computers they would automatically receive any files I had uploaded, and vice versa. Taking advantage of this technology for pedagogical purposes I set up the Dropbox folder and invited those students who I knew could not attend class. In this folder at the beginning of the Trimester I added a series of files. Some of these files mirrored those important files that could also be accessed via GCU Learn, but other files were created exclusively to support the non-class-based students. These files were versions of my lecture and workshop slides from GCU Learn that had an additional audio track. These files were available only through Dropbox and contained in a special folder called LECTURES WITH SOUND. During each week the same short lecture was given to three different classes and it was heavily contextualised to each design specialism. One of these lectures was recorded into my iPhone using an audio recording app in real-time. Then the Powerpoint lecture slides were exported as separate images, and using video editing software a movie of that week’s lecture was made with the slide changes edited to the audio points in the voiceover track. This did take extra time on my part to do, but it enabled those non-classbased students to follow that week’s lecture at the same time as their class-based peers, and not fall behind. I gave two lectures on a Monday and one on a Friday, so all those students who were abroad would be able to access the voiced lectures midweek. In total there were four lectures and two workshops that were available in this format. One student studying abroad wrote in an email soon after the uploading of a lecture movie, “I listened to the lecture and checked out the slides, and I'm glad that at least couple of my propositions for the research are correct.” In this way I could gauge how effective this method had been. Through Dropbox it could be tracked who had joined the folder but not whether a student had watched the video. As a strategy in blended learning this Dropbox folder was simply a resource for student-centred learning containing tools and guidance, and not an end in itself. To ensure that students were engaging in their own learning, one-to-one tutorials via Skype was also used by myself. Skype is a free person-to-person video conferencing app for computers with a Wi-Fi/Broadband connection. I required each student to attend two tutorials during the module whether in class or abroad. These were either group tutorials based on research subject or individual tutorials. Students could request additional tutorials (time permitting) and also they could email the staff questions. In the same way those studying abroad had exactly the same access to a staff member. When it came to presentations those students studying abroad still had to present their research-in-progress at weeks six to seven. They could negotiate how they would do this within the same presentation structure applicable to all students. The style of presentation was based upon the Japanese Pecha Kucha structure with some alteration to suit the Learning Outcomes, timetabling and number of students to observe and assess. Pecha Kucha (P.K.) is a quick (20 slides x 20 seconds per slide) and informal method used by designers globally to communicate their work to others. The structure I devised was dubbed ‘Pesky Koala’ as it was a variation of the P.K. style. This name also helped to reduce student anxiety towards presenting their own work through the use of humour (Frymier et al., 2008; Schacht & Stewart, 1990). As Susan Einbinder points out “chronic and acute stresses can erode self-esteem and sense of competence, giving rise to fears of failure and procrastination and raising the likelihood of earning a failing grade” (Einbinder, 2012, pp3-4). The structure for the ‘Pesky Koala’ presentation had a format where the student would show 10 slides, each for 20 seconds (forwarded automatically). The student would speak along to them and would restrict their delivery to 20 seconds per issue. The slides could contain images, diagrams or text but each student had to ensure they communicated their research journey with a beginning, middle, and an end. The majority of students studying abroad decided to mirror my lecture movies and add 20-second audio files to their slides and submit them via Dropbox for me to assess. A minority opted for a Skyped presentation. PART 3: Case Study Two PROGRAMME LEAD FOR BA(HONS) ENTERTAINMENT MEDIA DESIGN: Curriculum Development, Implementation and Student Blogging In 2008-09, the academic year before I joined Glasgow Caledonian University, I was the programme leader for the undergraduate degree BA(Hons) Entertainment Media Design at St Helens College. This top-up degree would articulate St Helen College’s existing Foundation Degree students onto a final year after they graduated their current two-year design degrees. To achieve this I led a validation team to develop the degree, and I was the principal author in its writing and presentation to the validation board in 2008. This case study will evidence the implementation of the curriculum that I had designed, exploring Areas of Activity and how my Core Knowledge and Professional Values were applied. The degree was designed to give design students from games design, graphic design, interactive multimedia, and photography a shared curriculum structure within which they could pursue their design specialisms to Honours level. The delivery of the degree was supported between designated module leaders (ML) and specialist tutors (ST). The cohort of students progressing onto an Honours year in St Helens would be small due to the small numbers on the final year of the articulated Foundation Degrees. In the first year of delivery there were only five full-time and four part-time students, Four students progressed from FDa Games Design, who were day-release students from Sony Computer Entertainment. The degree, as it was one final top-up year, had three modules (Pre-production, Production and Dissertation) each delivered by a ML. The STs that augmented this delivery comprised of one subject specialist from the FDa Photography teaching team and one from the FDa Game Design teaching team. In addition the day release students also secured themselves industry mentors (IM) from Sony Computer Entertainment’s art department. Alongside this support students embraced their independent learning and reflective learning through a personal blog and access to a central degree blog http://www.ba-emd.blogspot.co.uk/. These blogs encouraged students’ active learning (Kellum et al., 2001), cooperation among students (Halpern & Hakel, 2003) and prompt feedback (Kelly, 2009) from both staff and peers via the comment function on each student post. Active Learning The degree I wrote had a very student-centred curriculum focussed through the three modules, that on completion students would gain a BA(Hons) degree top-up to their existing Foundation Degree qualification. As each student brought their own design specialism to this degree the structure of the curriculum I decided on, through consultation with the validation team, creatively led to what can be described as “authoritative studentcentred teaching [through] treating students as responsible adults” (Upton and Bernstein, 2011, p358). As programme leader (PL) I began this even before the student graduated their FD. I gave prospective students clear information about the course, my teaching philosophy and what I was offering them. At interview this continued with an outline of their rights and obligations, and then at induction I reminded them it was ‘their degree.’ This corresponded with what Upton and Bernstein recommend. The nature of the student’s own specialist design knowledge meant that through the support of their ML and specialist tutor ST, each student took control of their own curriculum. Within the Learning Outcomes on each module the student would devise their own plan of study, supplemented by additional teaching of skills through workshops, seminars and tutorials. They would be advised and directed where they would be expected to gain extra knowledge and skills through their own independent learning. This level of active student-centred learning engaged each student to maximise their own learning potential. They found that they could do something more than just watch and listen to a lecture because lectures where few and mostly seminar-based. The students worked instead on the development of their full skill-sets through practice, theory and dissemination, rather than passively absorbing information from a teacher-centric ‘Sage on the Stage’ (King, 1993) approach. This meant I expected each student to focus on asking the question “What does it mean?” instead of “What am I supposed to remember?” (Bonwell & Eison, 1991) in order that their thinking about the coursework was at a higher order than when on their FD. Active learning methods that I personally applied in my teaching on the Pre-production and Dissertation modules helped students relate their new learning to what they already knew from the own FD education which was more formal in its classroom delivery. I encouraged the experimentation of their learning through practical iterative design experiments suitable to their design specialisms based on research they had undertaken themselves. This was in line with the QAA Art and Design Subject Benchmark Statement and what is considered to be fundamental to student’s typical standard of achievement (QAA, 2008, p7). This brought together their theoretical academic research for the Dissertation module and their more applied research together with two separate outcomes: project planning and drawing in Pre-production and a written thesis in the Dissertation module. This approach helped each student with differing abilities to engage more with the expected coursework and attain for themselves achievements that they would not have achieved within their FD. Weaker students still found this transition from 2nd year undergraduate study to Honours year study difficult, but overall engaged with the programme and all students graduated. Students gained confidence through this active learning partnership with their lecturers, and attained higher levels of achievement from their own personal engagement with their coursework (one student gained a First class degree). It was through the flexibility I designed into the degree that such student-centred adaptation of the curriculum became possible. This flexibility was later adapted after I left St Helens College in the writing of a new BA(Hons) Game Art degree which built on what I had innovated. This degree was validated in 2012 by the University of Chester. I was asked to be an External Academic advisor to the validation panel and it was rewarding to see that after four years my initial innovations in the active learning in St Helens was still being implemented. Cooperation Amongst Students As PL I had a strategic level of control over the teaching on this degree, and I have outlined how this impacted at a modular level as both a ML for Pre-production and a ST for Dissertation. What augmented this delivery was the level of cooperation amongst the students themselves in aiding each others’ learning. This is evidenced through the BAEMD course blog that I set up at the beginning of semester one in 2008. It took me ten blog posts (showing examples of project work that would inspire the students) before a student felt confident enough to make a post of their own. By their second post they had received a comment from their own IM from Sony Computer Entertainment. What was useful by this interaction that although the IM was solely a mentor to just that student they had made their industrial knowledge available to all the students via the blog. This type of dissemination of knowledge from industry on the blog would encourage students to at least keep reading future posts even if they never contributed posts themselves. Soon another student felt ready to post samples of their own, which resulted in three more students offering guidance on software tutorials, drawing and theory. By the end of the first semester nearly all the students had made at least one post, and three students were quite active posters. In all there were 52 posts made on the blog in 2008 and a further 125 in the 2nd semester in 2009. Kerawalla et al. (2008) provide a framework that focuses on four behaviours behind student blogging decisions: Audience, Comments, Community, and Presentation that maps to my students engagement with the degree blog. Halpern and Hakel state that one of the principles in human learning is that the “best way for students to learn and recall something will thus depend on what you want learners to learn and be able to recall, what they already know, and their own beliefs about the nature of learning” (2003, p40). By augmenting their class-based learning with a voluntary resource like the blog (that they feel a sense of collective ownership with) had led some of the students to begin to believe in their abilities and learn through a sense of what Kerawalla calls Community. In regards to what students already knew some found a way of gaining the confidence to share their knowledge on the blog and gain immediate validation that they were correct. This brave step of Presentation also meant they risked not being correct, but the sense of safety within their Community allowed some students to actively (and frequently) to take that risk. With guidance potentially coming from peers, IMs, and staff, about half the cohort actively sort an Audience to challenge their own beliefs in what they thought they knew. This meant that as PL/ML/ST my role in each student’s learning became one resource amongst many that they individually utilised. By the end of the second semester the nature of the posts gave way to showing actual design work-in-progress and the students who engaged in this Presentation, actively sought extra feedback that could immediately be provided by MLs/STs/IMs (or even peers), especially outside of class time. Prompt Feedback Not only did the degree blog offer prompt feedback from myself it also garnered more discussion between students. Out of the 125 posts in semester two 49 of those posts made by students needed feedback. These posts can be further split into five categories of desired feedback for: work-in-progress (32), written work (11), academic referencing (2), technology- related (2) and other course-related (2). Out of these 49 posts I only personally made 38 feedback comments whereas five students together made 36 in total to each other. At the beginning these where complimentary statements of “cool” and “sweet” but as the work began to show deeper development of their designs the comments became more constructively critical. Statements such as “The only thing Id (sic) change is the colour of the background mate, apparently concept art should never be grey on grey” (Jones, 2009), and “thats looking alot (sic) better now that you have lowered the seat. (…) I would sugest (sic) to put the old concept next to this one on this post so everyone can see the difference between the two easily” (Chabeaux, 2009) both show the level of support that students provided each other through the blog. In doing so it helped me to develop a sense of Community within the cohort, giving immediate feedback were needed or directing the student to seek a face-to-face tutorial with the ML or a ST when a more detailed response was needed. Students began to answer each other’s questions. This was very rewarding to read and I could promptly redirect students if they were misinformed and reward everyone when they had given the correct advice. At one point, three other students answered one student’s question about their dissertation without myself having to get involved. This formatively helped both the Dissertation ML and myself as PL to gauge the level of understanding and learning within an active section of the cohort. As the blog was not private two external readers of the blog who were thankful for the resource they had found also commented on an answer I made to a student about referencing. It did appear though that the majority of posts were from the stronger students who actively sought feedback. But weaker students who were less confident in their abilities also posted. In cases like these my feedback promptly praised their submission “Good to see stuff going up. Problems will always happen, but the strength is in how you overcome them.” and then constructively ushered them to develop further “Let's see a load more of these analytic tests at the group crit next week. The more you do the quicker you'll learn the software and you'll become more productive” (Wood, 2009d). I was conscious that these students had taken a big chance and that the feedback they read would be public, adding another potential anxiety. So my comments would be further contexualised in class so that the feedback comments could be explained further, if necessarily, face-toface. This would be done either in an individual tutorial or as part of a group discussion. That students would be able to understand and ask further questions when they didn’t understand. References BIENNIALFREERUNNER (2008) Entire Blog. 23rd April - 30th October. biennialFreerunner Blog [online]. [Accessed 6th August]. Available from: http://biennialfreerunner.blogspot.com. BONWELL C. and EISON, J. (1991) Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. ASHE–ERIC Higher Education Report No1. Washington, DC: The George Washington University School of Education and Human Development. CHABEAUX, S. (2009) Concept Motorcycle. 1st May. BA(HONS) Entertainment Media Design Blog [online]. [Accessed 4th August 2013]. Available from: http://baemd.blogspot.co.uk/2009/04/concept-motorcycle.html. EINBINDER, S.D. (accepted for publication March 2012) Reducing Research Anxiety Among MSW Students. Journal of Teaching in Social Work [online]. [Accessed 2nd August 2013]. Available from: http://www.csupomona.edu/~facultycenter/symposium/materials/Poster15_SusanEinbin der_2of2.pdf. FRYMIER, A.B., WANZER, M.B. & WOJTASZCZYK, A.M. (2008) Assessing Students’ Perceptions of Inappropriate and Appropriate Teacher Humor. Communication Education, 57(2), pp266-288. HALPERN, D.F. & HAKEL, M.D. (2003) Applying the Science of Learning to the University and Beyond: Teaching for Long-Term Retention and Transfer. Change. July/August, pp36–41. JONES, D.C. (2009) Vehicle Concept. 1st May. BA(HONS) Entertainment Media Design Blog [online]. [Accessed 4th August 2013]. Available from: http://baemd.blogspot.co.uk/2009/05/vehicle-concept.html. KAMLER, B. and THOMSON, P. (2006) Helping Doctoral Students Write: Pedagogies for Supervision. New York: Routledge. KELLUM, K.K., CARR, J.E. & DOZIER, C.L. (2001) Response Card Instruction and Student Learning in a College Classroom. Teaching of Psychology. 28(2), pp101–104. KELLY, K.G. (2009). Student Response Systems (‘Clickers’) in the Psychology Classroom: A beginners’ Guide. Society for Teaching of Psychology [online].[Accessed 13 July 2013], pp1-19. Available from: http://teachpsych.org/resources/Documents/otrp/resources/kelly09.pdf. KERAWALLA, L., MINOCHA, S., KIRKUP, G., and CONOLE, G. (2009) An Empirically Grounded Framework to Guide Blogging in Higher Education. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning. 25, pp31–42. KING, A. (1993) From Sage on the Stage to Guide on the Side. College Teaching. 41(1), pp30-35. MACDONALD, J. and CREANOR, L. (2010) Learning with Online and Mobile Technologies: A Student Survival Guide. Farnham: Gower. OLIVA, P. F. (1992) Developing the Curriculum. Third Edition. New York, HarperCollins Publishers. QAA (2008) Subject Benchmark Statement: Art and Design [online]. Gloucester: The Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. [Accessed 4th August 2013]. Available from: http://www.qaa.ac.uk/Publications/InformationAndGuidance/Documents/ADHA08.pdf. SCHACHT, S. and STEWART, B.J. (1990) What’s funny about statistics? A technique for reducing student anxiety. Teaching Sociology, 18(1), pp52-56. STAKER, H and HORN, M.B. (2012) Classifying K–12 Blended Learning. Innosight Institute. [Accessed 9th July 2013], pp1-17. Available from: http://www.innosightinstitute.org/innosight/wp-content/uploads/2012/05/Classifying-K12-blended-learning2.pdf. SUAREZ-GOLBORNE, S. (2007) Hyper Island: Workshop: Juho Parviainen and IDEO. [Accessed 12 May 2009]. Available from World Wide Web: http://hyperisland.blogspot.com/2007/10/workshop-juho-parviainen-and-ideo.html. UPTON, D. and BERNSTEIN, D.A. (2011) Creativity in the Curriculum. The Psychologist [online]. 24(5), pp356-359. Available from: http://www.thepsychologist.org.uk/archive/archive_home.cfm?volumeID=24&editionID= 200&ArticleID=1846. WOOD, D and KRAKIEWICZ, S.J. (2008) Traceur Tag: Developing IDEO ‘T-shaped’ People Whilst Producing a Student CG Video for Liverpool Biennial 08. Academia.edu [online]. [Accessed 6th August]. Available from: http://www.academia.edu/attachments/25267376/download_file. WOOD, D (2009a) Non-Norm: An Illustration Retrospective 1991-01. Liverpool: NMBazaar. WOOD, D (2009b) Baby’s Square Astrology Book (cheeky sceptics). Liverpool: NMBazaar. WOOD, D. (2009c) Interaction Design: Where's the Graphic Designer in the Graphical User Interface? In: International Association of Societies of Design Research. IASDR 2009, 18-22 October, Seoul, Korea. Republic of Korea: IASDR, p135. WOOD, D. (2009d) Update. 3 March. BA(HONS) Entertainment Media Design [online]. [Accessed 4th August 2013]. Available from: http://baemd.blogspot.co.uk/2008/09/welcome-to-your-ba-blog.html. WOOD, D. (2010) Moving Across The Boundaries: Visual Communication Repositioned In Support of Interaction Design. In: J. BONNER, M. SMYTH, S. O’NEILL, and C. MIVAL, (Eds). Create 10: the Interaction Design Conference, June 30 - July 2nd, 2010, Edinburgh, UK. London: The Institute Of Ergonomics And Human Factors, BCS The Chartered Institute For IT Interaction Specialist Group and Edinburgh Napier University, pp27-32. WOOD, D. (2011) A Can of Worms: Has Visual Communication a Position of Influence on Aesthetics of Interaction? Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal. 5(3). pp463-476. WOOD, D. (2013) Interface Design: An Introduction to Visual Communication in UI Design. London: Bloomsbury Publishing [in press]. Email This BlogThis! Share to Twitter Share to Facebook Share to Pinterest