Evidence Outline

SUMMARY of ADMISSIBLE EVIDENCE.

● Preliminary questions:

○ 1. What is the piece of evidence?

○ 2. What is it being offered to show?

■ Is what it is being offered to show an element of the claim or crime?

● Substantive Evidence:

○ 1. Authentic

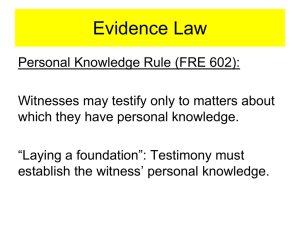

○ 2. From competent witnesses or declarants

○ 3. With personal knowledge (except for SOPO)

○ 4. That’s relevant

○ 5. That’s not excluded by:

■ Hearsay

■ Prejudice

■ Best evidence rule

■ Privilege

■ Opinion rule

■ Any other exclusionary rule outside the FRE

○ 6. Whose probative value is not substantially outweighed by its prejudicial effects, or other FRE 403 counterbalances.

● Impeachment Evidence:

○ 1. Relevant impeachment material regarding those witnesses and declarants that meets various tests for impeachment evidence and passes a 403 balance when necessary.

● + Procedural Rules.

○ E.g. 103, 105, 106, 405, 611, especially 104.

PROCEDURAL RULES

Objections and Appeals

● FRE 103. Rulings on Evidence.

○ (a) Preserving a Claim of Error. A party may claim error in a ruling to admit or exclude evidence only if the error affects a substantial right of the party and:

■ (1) if the ruling admits evidence, a party, on the record:

● (A) timely objects or moves to strike; and

● (B) states the specific ground, unless it was apparent from the context; or

■ (2) if the ruling excludes evidence, a party informs the court of its substance by an offer of proof, unless the substance was apparent from the context.

○ (b) Not Needing to Renew an Objection or Offer of Proof. Once the court rules definitively on the record — either before or at trial — a party need not renew an objection or offer of proof to preserve a claim of error for appeal.

○ (c) Court’s Statement About the Ruling; Directing an Offer of Proof. The court may make any statement about the character or form of the evidence, the objection made, and the ruling. The court may direct that an offer of proof be made in question-and-answer form.

○ (d) Preventing the Jury from Hearing Inadmissible Evidence. To the extent practicable, the court must conduct a jury trial so that inadmissible evidence is not suggested to the jury by any means.

○ (e) Taking Notice of Plain Error. A court may take notice of a plain error affecting a substantial right, even if the claim of error was not properly preserved.

● Notes on FRE 103:

○ (a) When evidence rules are broken, party has responsibility to object when the error affects a substantial right of the party.

■ (2) If evidence is excluded by the trial judge, the party should inform the trial judge of what the evidence would have said away from the jury, so on appeal the appellate court can decide whether the trial judge should have excluded the evidence.

○ (e) If a party should have objected to the admittance of evidence but failed to, the trial court may note that admittance of that evidence is “plain error” to avoid being overturned on appeal.

■ Note: Appellate Review. Three steps of appellate review of wrongly-admitted evidence:

● Procedural Default. First, appellate court reviews whether the party objected during trial. If they did not object, it might be a procedural default and the appeal does not stand.

● Merits. Second, if the party did object, was the trial judge wrong in not sustaining the objection?

● Harmless Error. Third, if the party objected, the trial judge was wrong, did the judge’s decision affect the outcome or was it merely harmless error?

Evidence Admissible, But Not Against Other Parties

● FRE 105. Limiting Evidence That Is Not Admissible Against Other Parties or for Other

Purposes.

○ If the court admits evidence that is admissible against a party or for a purpose — but not against another party or for another purpose — the court, on timely request, must restrict the evidence to its proper scope and instruct the jury accordingly.

Preliminary Fact Questions

● FRE 104. Preliminary Questions.

○ (a) In General. The court must decide any preliminary question about whether a witness is qualified, a privilege exists, or evidence is admissible. In so deciding, the court is not bound by evidence rules, except those on privilege.

○ (b) Relevance That Depends on a Fact. When the relevance of evidence depends on whether a fact exists, proof must be introduced sufficient to support a finding that the fact does exist. The court may admit the proposed evidence on the condition that the proof be introduced later.

● Notes on FRE 104.

○ When a preliminary fact needs to be found to exist in order for evidence to be relevant, the judge decides if there is “sufficient” evidence for it to be admitted and go to the jury for preponderance of the evidence consideration (104(b).

Otherwise, preliminary questions about fact admissibility are decided by the judge under a preponderance of the evidence standard.

■ EX. Shooting in library. A Cubs pin is found at the scene of the shooting.

That pin is only relevant if a suspect shooter is a Cubs fan. Therefore the jury must decide whether the shooter is a Cubs fan under 104(b).

○ Summary of burdens of proof.

■ 104(a). “Preponderance of the evidence.”

■ 104(b). “Sufficient evidence” that a “reasonable jury could find.”

Burdens of Proof

● Burden of Persuasion. A measure set by the law of how probable the trier of fact must assess a proposition to be if the trier is to determine that proposition in favor of a given party (e.g. beyond a reasonable doubt, preponderance of evidence).

● Burden of Production. Refers to a party's obligation to come forward with sufficient evidence to support a particular proposition of fact.

RELEVANCE

Relevancy - General

● Relevancy. Exists as a relation between an item of evidence and proposition sought to be proved. If an item of evidence tends to prove or disprove any proposition, it is relevant to that proposition.

○ Note: Different than admissibility; an item could be relevant but not admissible under another rule.

● FRE 401. Test for Relevant Evidence

○ Evidence is relevant if:

○ (a) it has any tendency to make a fact more or less probable than it would be without the evidence; and

○ (b) the fact is of consequence in determining the action.

● Notes on FRE 401.

○ (a) Logical relevance. Any tendency to make a fact more or less probable.

■ “Any Tendency.” Probative value. The evidence does not need to directly or necessarily prove something, only draw an inference.

● Sherrod v. Berry.

○ I: Whether evidence showing that the deceased had no weapon on him at the time he was shot by a police officer

(even though the officer did not know that at the time of the shooting) was relevant in a civil rights action against the officer.

○ H: No. Evidence beyond that which the officer had and reasonably believed at the time he fired his gun is irrelevant to whether he acted reasonably under the circumstances, which is the element of the crime that needs to be proven.

● Knapp v. State.

○ I: Whether the following evidence was admissible: defendant claimed he heard a story that a marshall had killed a man, and defendant used this story to bolster his claim that he killed the marshall in self-defense because he feared for his life; prosecution admits evidence showing that the marshall had not killed the other man.

○ H: Yes. The prosecution’s evidence was relevant because it tended to disprove the defendant’s self-defense testimony. In other words, although proving that the marshall had not killed another man would usually be irrelevant to defendant’s trial, here it became relevant because it tended to disprove an item of defendant’s self-defense claim.

■ EX. Shooting in library. Start with concrete fact (shooting in library and someone running away), general unarticulated premise (guilty people and shooters generally flee the scene of shooting), and draw an inference.

○ (b) Legal relevance. The target of consequence needs to be legitimate, i.e. an element of the crime.

■ Conditional Relevance. Some facts are not relevant unless they are conditioned or attached to another relevant fact.

● EX. Shooting in library. A Cubs pin found near a body has no relevance, unless it is attached to another fact, like the suspected shooter being a Cubs fan. Note that if a swastika pin was found instead, then prejudice versus probative value analysis needed.

● FRE 403. Excluding Relevant Evidence for Prejudice, Confusion, Waste of Time, or

Other Reasons.

○ The court may exclude relevant evidence if its probative value is substantially outweighed by a danger of one or more of the following: unfair prejudice,

confusing the issues, misleading the jury, undue delay, wasting time, or needlessly presenting cumulative evidence.

● Notes on FRE 403.

○ FRE 403 Balancing Test. Relevant evidence must be examined item by item for

(1) probative value and (2) prejudicial risk. If the prejudicial risk “substantially outweighs” the probative value, the court may exclude the evidence (especially in cases where a less-prejudicial alternative exists).

○ Old Chief v. US (Supreme Court)

■ I: Whether in a criminal case under a statute prohibiting a past felon to possess a firearm, the district court abuses its discretion by admitting into evidence the nature of the felon’s previous crime solely to prove the element of prior conviction of a gun-related felony, when: Old Chief committed felony of aggravated assault with a gun, then is later charged with the statute prohibiting felons to possess firearms.

■ H: Yes, the court abused its discretion, because the evidence’s prejudicial risk outweighed its probative value, especially when other probative evidence would serve the same purpose (such as an admission of

“having committed a past felony” rather than admitting into evidence what the felony was).

● R: Evidence of the name or nature of a prior offense generally carries a risk of prejudice.

● R: Relevant evidence is not inadmissible just because other evidence exists that is sufficient to make the original evidence irrelevant. Rather, both pieces of evidence should be analyzed for prejudice.

● R: “Unfair Prejudice.” Evidence with an undue tendency to suggest decision on an improper basis, commonly an improper emotional basis. Improper bases include generalizing a defendant’s earlier bad act into bad character to make it more likely for the jury to find the defendant guilty of the current accusation (see also FRE 404 and 405).

○ Ballou v. Henri Studios

■ I: [1] Whether the district court erred by believing a nurse’s testimony that defendant was drunk at the time of a fatal vehicle accident rather than a blood test showing that defendant was not drunk, because the court found that the test was “uncredible.” [2] Whether the blood test carried a risk of unfair prejudice that outweighed its probative value.

■ H: [1] Yes, the court erred. The court should do a relevancy and prejudice analysis of evidence, but whether evidence is “credible” is a decision that is left to the jury. [2] No. The evidence is highly probative to the issue of defendant’s contributory negligence in the fatal accident; the judge mistook highly probative value for prejudicial value because both influence the jury.

Character Evidence

● FRE 404. Character Evidence and Other Acts Evidence.

○ (a) Character Evidence.

■ (1) Prohibited Uses. Evidence of a person’s character or character trait is not admissible to prove that on a particular occasion the person acted in accordance with the character or trait.

■ (2) Exceptions for a Defendant or Victim in a Criminal Case. The following exceptions apply in a criminal case:

● (A) a defendant may offer evidence of the defendant’s pertinent trait, and if the evidence is admitted, the prosecutor may offer evidence to rebut it;

● (B) subject to the limitations in Rule 412 (sex offense cases), a defendant may offer evidence of an alleged victim’s pertinent trait, and if the evidence is admitted, the prosecutor may:

○ (i) offer evidence to rebut it; and

○ (ii) offer evidence of the defendant’s same trait; and

● (C) in a homicide case, the prosecutor may offer evidence of the alleged victim’s trait of peacefulness to rebut evidence that the victim was the first aggressor.

■ (3) Exceptions for a Witness. Evidence of a witness’s character may be admitted under Rules 607, 608, and 609 (impeachment rules).

○ (b) Crimes, Wrongs, or Other Acts.

■ (1) Prohibited Uses. Evidence of a crime, wrong, or other act is not admissible to prove a person’s character in order to show that on a particular occasion the person acted in accordance with the character.

■ (2) Permitted Uses; Notice in a Criminal Case. This evidence may be admissible for another purpose, such as proving motive, opportunity, intent, preparation, plan, knowledge, identity, absence of mistake, or lack of accident. On request by a defendant in a criminal case, the prosecutor must:

● (A) provide reasonable notice of the general nature of any such evidence that the prosecutor intends to offer at trial; and

● (B) do so before trial — or during trial if the court, for good cause, excuses lack of pretrial notice.

● FRE 405. Methods of Proving Character.

○ (a) By Reputation or Opinion. When evidence of a person’s character or character trait is admissible, it may be proved by testimony about the person’s reputation or by testimony in the form of an opinion. On cross-examination of the character witness, the court may allow an inquiry into relevant specific instances of the person’s conduct.

○ (b) By Specific Instances of Conduct. When a person’s character or character trait is an essential element of a charge, claim, or defense, the character or trait may also be proved by relevant specific instances of the person’s conduct.

● Notes on FRE 404 and 405.

○ Character Evidence. Three ways it may be admitted:

■ 1. Admitted to show a general character trait, when shown only by the following methods: (1) reputation or (2) opinion. Must be admitted without reference to specific acts, and by a defendant in a criminal trial

(prosecution and civil parties cannot admit evidence of good or bad character for anyone).

● EX. Aggie is witness for defendant; she gets on stand and generally testifies about defendant’s reputation as an honest person. She cannot testify about specific times defendant was honest.

■ 2. Admitted for another purpose other than to show that defendant is more likely to commit the currently-tried crime, when shown by the following methods: (1) reputation, (2) opinion, or (3) sometimes specific acts when the act fits under the exceptions in 404(b)(2) (e.g. handiwork, intent, identity, etc.), or when the witness is being cross-examined about their character testimony.

■ 3. Admitted to prove an element of a crime (e.g. defamation cases, when you have to prove you are not the person that someone says you are), when shown by (1) reputation, (2) opinion, and (3) specific acts evidence.

○ 404(b)(2) Exceptions. Other Criminal Acts Evidence. Prosecution cannot use evidence of defendant’s other criminal acts to show that defendant is a person of

“criminal character” and is thus more likely to commit the crime being tried.

Rather, prosecution can use the evidence:

■ 1. Complete Story. To complete the story of a crime by placing it in context with nearby or nearly contemporaneous happenings; only applicable where reference to the other crimes is essential to a coherent and intelligent description of the crime being tried.

■ 2. Conspiracy. To prove the existence of a larger plan, scheme, or conspiracy of which the crime on trial is a part.

■ 3. Handiwork. To prove other crimes by the accused so nearly identical in method as to earmark them as the signature and handiwork of the accused,

● EX. Serial killers, Bride Bathtub drownings, modus operandi.

■ 4. Purposefulness and Knowledge. To show by similar acts or incidents that the act in question was not performed inadvertently, accidentally, involuntarily, or without guilty knowledge.

● EX. Makin v. Attorney General of New South Wales. The fact that baby corpses were found at all the places where a couple had lived in the past should allow prosecutors to add evidence of other missing children to the prosecution of the couple for a murder of a baby.

■ 5. Motive. Probative evidence may show malice or specific intent from previous actions.

● EX. Husband beats and threatens wife for years. Later wife is murdered. The domestic abuse may be evidence of husband’s intent to kill her.

■ 6. Opportunity. In the sense of access to or presence at the scene of a crime, or in the sense of possessing distinctive or unusual skills or abilities employed in the commission of the crime charged.

● EX. A burglar’s past acts show a knowledge of how to deactivate alarm systems.

■ 7. Intent. To show, without considering motive, that defendant acted with malice, deliberation, or the requisite specific intent.

■ 8. Identity. This is a very narrow category and is usually only admitted in conjunction with showing past motive, opportunity, larger plan, or modus operandi. In and of itself evidence is not admitted solely to show identity.

■ 9. Propensity for Abnormal Sex Acts. To show a passion or propensity for unusual and abnormal sexual relations.

■ 10. Impeachment. To impeach an accused who takes the witness stand by introducing past convictions.

○ Cleghorne v. New York Central

■ I: Whether evidence of a railroad switchman’s “intemperance” may be admitted to show that the railroad company was negligent in hiring him, in a case deciding the railroad company’s negligence in an accident caused by the switchman.

■ H: Yes; however, the evidence of the switchman’s “intemperance” and drunkenness is only usable against the railroad company because they are another party (it is admissible under FRE 405(b), which allows evidence of specific acts if they are an element of the crime, which was the case here - not in facts); the evidence would not be usable against the switchman because then it would be character evidence. See FRE 105

(limiting instruction needed when evidence is admissible against one party but not another).

● R: Character evidence may be admissible for one purpose, but not admissible for another purpose. In that circumstance, a limiting instruction from the court is needed.

○ Michelson v. US (Supreme Court)

■ I: Whether the prosecution during cross-examination can question character witnesses about past criminal arrests (not convictions) of the defendant, when defendant is tried for bribery and puts character witnesses on the stand to offer opinions about his reputation for honesty.

■ H: Yes. Arrests, even without convictions, are part of the reputation of defendant, and weaken the witnesses’ testimonies that defendant is a law-abiding individual. Although the arrests mentioned in cross

examination were old and remote and unrelated to the current crime, they may still be known to the community and therefore useful in deciding defendant’s reputation; it is not per se an abuse of discretion to admit that evidence.

● R: Character Witness. Does not need to be an expert. Testifies as to a defendant’s reputation, or from personal opinion, rather than specific acts of defendant. A character witness can be cross-examined about specific acts that go against the witness’s testimony that defendant has a certain reputation.

● R: Accused may present evidence indicating that his character makes it less likely that he committed the crime. Prosecution can then admit character evidence in rebuttal.

○ Note: Here, defense counsel asked “is defendant a law abiding citizen?” which gave prosecution broad range to talk about defendant’s character. Otherwise, prosecution would have been limited to just talking about the character trait asked about on direct.

● R: Prosecution cannot prove that the accused is more likely to have committed the crime charged because he has an evil character or has committed other bad acts in the past.

● R: On cross-examination of a character witness, inquiry as to specific incidents is permissible in the discretion of the trial judge.

○ US v. Carrillo

■ I: Whether evidence of defendant’s two past sales of controlled substances in an area near a Club may be admitted to help establish the identity of defendant, when: defendant on one previous occasion sold drugs by a Club, on another previous occasion sold drugs from his house in balloons, and in the currently-tried case he was arrested for selling heroin in balloons by the Club but he uses mistaken identity as a defense.

■ H: No, the evidence cannot be admitted. First, because prosecution can only show “identity” with extrinsic act evidence if the identity is in conjunction with something else, like M.O. or intent; here, the extrinsic evidence does not show anything (in particularly does not show handiwork of defendant, because balloons are common for distributing drugs).

● R: Two part test for admitting extrinsic act evidence:

○ (1) The extrinsic act evidence is relevant to an issue in the case other than defendant’s character.

○ (2) The evidence has probative value not substantially outweighed by prejudicial risk.

○ US v. Beasley

■ I: Whether prosecution can admit [1] evidence of defendant’s past drug dealing and [2] evidence of one of his alleged victim’s severe drug

addiction, to show that defendant intended to sell fraudulently-obtained drugs in the currently-tried case.

■ H: [1] Likely no. The past bad acts of drug dealing do not show “intent” in the current case, but only propensity to sell drugs, which is improper purpose for admitting “other acts” evidence (in modern case under FRE

404(b) it might be admissible to show intent). [2] No. This evidence does not show defendant’s intent in obtaining drugs from a doctor; further, it is highly prejudicial and of little probative value.

○ US v. Cunningham

■ I: Whether trial court abused its discretion in admitting evidence of prior bad acts of defendant (stealing and using a painkiller from her hospital job and falsifying drug tests) to establish the motive of defendant to steal the same painkiller in the currently-tried case.

■ H: No. The analysis here lies in the difference between “propensity” and

“motive;” whereas evidence of past bad acts cannot be admitted because it shows a mere propensity for committing a crime, evidence of past bad acts can be admitted to show motive to commit a crime. Here, mere evidence of her past theft of the painkiller only shows propensity, not motive, to steal in the current case. However, evidence of her past theft and drug test falsification tends to show that she is addicted to the painkiller, which provides a motive for her to steal the drug in the current case.

● R: Motive v. propensity.

○ Tucker v. State

■ I: Whether the trial court abused its discretion in admitting evidence of a factually-similar killing involving defendant, but of which defendant was never convicted of actually carrying out, when defendant calls police because he “finds” a dead body on his couch, and during trial the prosecution admitted evidence that defendant had called police on an earlier occasion when someone else mysteriously died in his apartment, but defendant was never convicted of murder in the earlier occasion.

■ H: Yes, the court abused its discretion. The court should not have admitted “other acts” evidence of something that defendant was never proven to have committed; i.e., the evidence was not “another act” of defendant.

○ Huddleston v. US

■ I: Whether the trial court must make a preliminary finding by a preponderance of the evidence that the government has proven defendant’s “other act” before the court submits the evidence to a jury, when: the court admits evidence that on a previous occasion defendant tried to sell hot appliances to an informant (but was not convicted) to show defendant's knowledge that he was selling hot goods to the same informant in the current case.

■ H: No, under FRE 104(b). 104(b) applies because the issue of whether defendant actually sold hot appliances in the past is relevant to show whether he had knowledge that he was selling hot goods in the present case. Therefore, under 104(b), the court’s job is only to make sure that there is sufficient evidence for the issue to go to the jury. The jury must then find, by a preponderance of the evidence, that defendant actually tried to sell hot appliances on the previous occasion. Thus, the judge erred by making this fact-finding here when it should have gone to the jury. Note that here the purpose for admitting the evidence was to show defendant's “knowledge” that the goods were stolen (because he had sold to the same informant before) rather than to show mere propensity to steal.

● R: FRE 104(a) versus 104(b).

● Note: “Other act” evidence is only relevant if it can be established, by a preponderance of the evidence, that the defendant actually committed the “other act” under 104(a). Under 104(b), there only

○ Dowling v. US needs to be “sufficient” evidence.

■ R: Double Jeopardy Clause is not implicated when a jury finds under FRE

104(b) by preponderance of the evidence that a defendant has committed a criminal act other than the one being currently tried.

Habit Evidence

● FRE 406. Habit and Routine Practice.

○ Evidence of a person’s habit or an organization’s routine practice may be admitted to prove that on a particular occasion the person or organization acted in accordance with the habit or routine practice. The court may admit this evidence regardless of whether it is corroborated or whether there was an eyewitness.

● Notes on FRE 406.

○ Habit versus Character.

■ Habit. One’s regular response to a repeated specific situation. Habit may be either an individual (repeated response) or organization (routine practice).

● Note: Evidence of a habit is admissible regardless of whether or not an eyewitness saw that the person had broken the habit at the time of an incident.

○ EX. Someone has a habit of wearing a seatbelt but was seen to not be wearing a seatbelt during the time of an accident; evidence of the habit may still be submitted.

● Note: Evidence of a habit is usually rejected because it is not frequent enough to be a habit or the regular response is a trait of character (e.g. you cannot have a “habit” of honesty).

● Note: Evidence that fails to be admitted under FRE 406 “habit” may still fit under FRE 404(b) “modus operandi” if it takes place less often.

○ EX. Arson.

■ Character. A generalized description of one’s disposition, or one’s disposition in respect to a general trait such as honesty or temperance.

○ Perrin v. Anderson

■ I: Whether the trial judge abused its discretion in allowing defendants to admit evidence of four occasions where Perrin went crazy when he ran into law enforcement officers, when defendants have evidence of eight situations when Perrin acted violently and irrationally when approached by police that they submit to show Perrin’s “habit” of bad behavior to cops.

■ H: No, the court did not abuse its discretion. The judge has to hear all the evidence of Perrin’s reactions to police in order to decide that Perrin’s activity constituted a “habit,” but then can choose to only present some of those incidents at trial to avoid unfair prejudice against Perrin (here, the judge allowed four of the eight incidents to be admitted).

● R: Habit. A regular practice of meeting a particular kind of situation with a certain type of conduct, or a reflex behavior in a specific set of circumstances. Must be shown by more than a few isolated incidents.

● R: A judge must look at all the evidence of defendant’s alleged

“habit” to decide whether a habit exists. However, the judge can choose to only admit some of the evidence of specific instances as representative of the habit.

○ Halloran v. Virginia Chemicals

■ I: Whether evidence that plaintiff had previously used an immersion heating coil to heat a can of refrigerant should be admissible to show that on the particular occasion of his injury from the can exploding he was negligent and used the immersion heating coil (despite a warning on the can not to).

■ H: Yes; the trial judge had discretion to decide that those previous times established plaintiff’s habit of heating refrigerant cans. Repetition of similar action in response to something gives rise to a reasonable inference of a habit. Here, the trial judge found that there was sufficient evidence to admit the evidence as habit.

● R: The trial judge has discretion to decide whether there is enough evidence of habit to submit the evidence to the jury for consideration.

○ Note: Cf. with Perrin case,

Prior Sexual Offenses

● FRE 412. Sex-Offense Cases: The Victim

○ (a) Prohibited Uses. The following evidence is not admissible in a civil or criminal proceeding involving alleged sexual misconduct:

■ (1) evidence offered to prove that a victim engaged in other sexual behavior; or

■ (2) evidence offered to prove a victim’s sexual predisposition.

○ (b) Exceptions.

■ (1) Criminal Cases. The court may admit the following evidence in a criminal case:

● (A) evidence of specific instances of a victim’s sexual behavior, if offered to prove that someone other than the defendant was the source of semen, injury, or other physical evidence;

● (B) evidence of specific instances of a victim’s sexual behavior with respect to the person accused of the sexual misconduct, if offered by the defendant to prove consent or if offered by the prosecutor; and

● (C) evidence whose exclusion would violate the defendant’s constitutional rights.

■ (2) Civil Cases. In a civil case, the court may admit evidence offered to prove a victim’s sexual behavior or sexual predisposition if its probative value substantially outweighs the danger of harm to any victim and of unfair prejudice to any party. The court may admit evidence of a victim’s reputation only if the victim has placed it in controversy.

● FRE 413. Similar Crimes in Sexual-Assault Cases.

○ (a) Permitted Uses. In a criminal case in which a defendant is accused of a sexual assault, the court may admit evidence that the defendant committed any other sexual assault. The evidence may be considered on any matter to which it is relevant.

● FRE 414. Similar Crimes in Child Molestation Cases.

○ (a) Permitted Uses. In a criminal case in which a defendant is accused of child molestation, the court may admit evidence that the defendant committed any other child molestation. The evidence may be considered on any matter to which it is relevant.

● FRE 415. Similar Acts in Civil Cases Involving Sexual Assault or Child Molestation

○ (a) Permitted Uses. In a civil case involving a claim for relief based on a party’s alleged sexual assault or child molestation, the court may admit evidence that the party committed any other sexual assault or child molestation. The evidence may be considered as provided in Rules 413 and 414.

● Notes on FRE 412 - 415.

○ Rape Shield Legislation. Limits the use of evidence of prior sexual conduct in sexual assault cases. Evidence of reputation and sexual behavior is not admissible purely for purpose of showing unchaste character. Admissible evidence (including prior acts evidence) includes:

■ 1. Complainant’s prior sexual behavior with defendant.

■ 2. Evidence of complainant's sexual behavior with other persons when offered for purposes of explaining physical consequences of the alleged rape (e.g. pregnancy, venereal disease, presence of semen, injury, etc. which may be caused by someone other than rapist).

○ State v. Cassidy

■ I: Whether the trial court abused its discretion in excluding the following evidence: victim claims she was raped by defendant, and defendant claims that he was having consensual sex with her when she suddenly went berserk and started yelling about her dead husband in Vietnam; at trial, defendant seeks to admit evidence that she exhibited the same bizarre behavior with another man who she falsely accused of rape.

■ H: No; the evidence was properly excluded as irrelevant because it involved someone other than defendant and did not establish a habit of conduct. Relevant sexual conduct is between defendant and victim, and defendant and victim have had sex before without the bizarre behavior transpiring.

○ Olden v. Kentucky (Supreme Court)

■ I: Whether petitioner was denied his Sixth Amendment right to confront witness against him, when Matthews (a white woman) accuses petitioner

(a black man) of raping her twice with the help of three other men and then dropping her off at the home of Russell her lover, and petitioner seeks to admit into evidence that Russell and Matthews were having an affair to prove motive that Matthews would lie to cover up her consensual sex with petitioner, but the trial court excludes that evidence.

■ H: Yes, petitioner was denied his Sixth right to confront his witness. Here, a reasonable jury could decide that Matthews lied about having consensual sex with petitioner to protect her relationship with Russell

(petitioner had a Sixth Amendment right to confront and impeach

Matthews’ testimony). Also, the exclusion of the evidence was not harmless error because: (1) Matthews’ testimony was central to her case,

(3) Matthews’ testimony was corroborated only by Russell, who would have been considered less persuasive if the jury had known about his relationship with Matthews, and (5) Matthew’s case was overall not overwhelmingly strong.

○ US v. Platero

■ R: The determination of whether there has been a sexual relationship at the critical time is a matter of conditional relevance that should be determined by the jury.

● Note: “If instead the trial judge proceeds to decide the preliminary relevancy-conditioned-on-fact issue against the proponent where the jury could reasonably find the fact to exist, the judge has violated the proponent’s right to a jury trial.”

○ Johnson v. Elk Lake School District

■ I: Whether the trial court used the correct standard for excluding evidence of past sexual assault under FRE 413 and 415, when Johnson (a teen girl) alleges that her teacher Stevens sexually harassed her, and Johnson seeks to admit evidence that Stevens on an earlier occasion picked up another teacher and touched her crotch area while doing so, but the court excludes the evidence because it was past sexual misconduct under FRE

413 and 415.

■ H: Yes, the trial court rightly decided (with discretion) that the evidence should be excluded under FRE 403 because the incident with the teacher has low probative value, but high prejudicial value against Stevens (i.e. majority of the factors under FRE 403 were against admitting the evidence).

● R: The standard for FRE 413-415 is that evidence can be discretionarily admitted or discluded under FRE 403 after considering these factors:

○ 1. The past act is substantially different from the act for which the defendant is being tried.

○ 2. The past act cannot be demonstrated with sufficient specificity.

○ 3. The past act is far away in time from the charged acts.

○ 4. The past act was infrequent.

○ 5. The past act was separated from the charged act by intervening events.

○ 6. Whether evidence based on testimony of the defendant and alleged victim is needed.

● R: “Offense of Sexual Assault” under FRE 413(d). Includes both prior convictions for sexual offenses as well as uncharged conduct, as long as the conduct is intentional.

Evidence of Similar Happenings

● Simon v. Kennebunkport

○ I: Whether the trial court erred in excluding evidence that other people (as many as 100 in one day) had fallen on a specific portion of the sidewalk, in a case to decide whether the town had been negligent in not repairing that portion of the sidewalk when an elderly woman slipped and fell there.

○ H: Yes, the court erred because it should have admitted the evidence as probative under the similar happenings rule. Such evidence is probative in a negligence action because it can show a defective or dangerous condition or notice thereof, and vice-versa (lack of accidents shows no defective condition).

Here, the evidence of 100 people falling in the same spot was highly probative to the material issue of whether the sidewalk was in defective condition when the woman fell; also, the town knew about the defective condition so they would not have been surprised by the evidence.

■ R: Similar Happenings Evidence. Trial court has discretion to admit evidence of similar incidents that occurred under “substantially similar” circumstances to the incident at issue, when that evidence is probative to an issue of defect, notice or causation. The trial court should exclude this evidence if it fails a 403 analysis.

● Note: In response, the opposing party can submit evidence of scores of times that incidents did not happen under substantially similar circumstances. For instance, here the town could give statistics of the thousands of people who walked on that portion of the sidewalk and did not trip or fall.

Evidence of Subsequent Precautions

● FRE 407. Subsequent Remedial Measures.

○ When measures are taken that would have made an earlier injury or harm less likely to occur, evidence of the subsequent measures is not admissible to prove:

■ Negligence;

■ culpable conduct;

■ a defect in a product or its design; or

■ a need for a warning or instruction.

○ But the court may admit this evidence for another purpose, such as impeachment or — if disputed — proving ownership, control, or the feasibility of precautionary measures.

● Notes on FRE 407.

○ Tuer v. McDonald.

■ I: Whether the trial court erred in excluding evidence that, after Mr. Tuer died when he was denied the drug Heparin while awaiting coronary artery bypass surgery, the defendant hospital changed the protocol regarding administration of Heparin to administer it to patients awaiting coronary bypass surgery.

● Note: Doctors had initially said that they could not administer

Heparin during pre-surgery time because it increased the risk of bleeding out if a mistake was made during the surgery, as Heparin is an anticoagulant. At trial, Tuer’s widow sought to include this remedial measure to prove two things: (1) feasibility for doctors to have used Heparin on her husband prior to his surgery, and (2) impeachment of the doctor’s testimony that not using Heparin prior to surgery was safe. Ms. Tuer argued these two points to get within FRE 407’s exceptions.

■ H: Yes, because Tuer’s widow (plaintiff) did not actually challenge the feasibility of the prior procedure or impeach the doctor’s testimony that the prior procedure was unsafe. Rather, there was no dispute about feasibility of the prior procedure; of course it was feasible, because it was medically possible, but the doctors merely said it was unadvisable because of the danger. As for impeachment, the court decided here that

the doctors still believed the same thing (i.e. that administering Heparin pre-surgery was dangerous), but slightly reevaluated their procedures.

● R: “Feasibility.” Generally interpreted as “physical possibility.”

Evidence of Offers in Compromise

● FRE 408. Compromise Offers and Negotiations.

○ (a) Prohibited Uses. Evidence of the following is not admissible — on behalf of any party — either to prove or disprove the validity or amount of a disputed claim or to impeach by a prior inconsistent statement or a contradiction:

■ (1) furnishing, promising, or offering — or accepting, promising to accept, or offering to accept — a valuable consideration in compromising or attempting to compromise the claim; and

■ (2) conduct or a statement made during compromise negotiations about the claim — except when offered in a criminal case and when the negotiations related to a claim by a public office in the exercise of its regulatory, investigative, or enforcement authority.

○ (b) Exceptions. The court may admit this evidence for another purpose, such as proving a witness’s bias or prejudice, negating a contention of undue delay, or proving an effort to obstruct a criminal investigation or prosecution.

● Notes on FRE 408

○ Davidson v. Prince

■ I: Whether the trial court erred in admitting into evidence statements that appellant made in a letter to appellee after appellant is injured by appellee’s steer, when in the letter appellant mentions he was ten feet away from the steer but at trial appellant says he was forty feet away from the steer.

■ H: No, the trial court did not err, because the letter did not fit into FRE

408’s exception for settlement negotiations. The letter written here was an attempt to inform appellee as to the facts of the in incident, not an offer to compromise appellant’s claim or as part of settlement negotiations.

Evidence of Offers to Pay Medical Bills and Similar Expenses

● FRE 409. Offers to Pay Medical and Similar Expenses

○ Evidence of furnishing, promising to pay, or offering to pay medical, hospital, or similar expenses resulting from an injury is not admissible to prove liability for the injury.

Evidence of Plea Discussions

● FRE 410. Pleas, Plea Discussions, and Related Statements

○ (a) Prohibited Uses. In a civil or criminal case, evidence of the following is not admissible against the defendant who made the plea or participated in the plea discussions:

■ (1) a guilty plea that was later withdrawn;

■ (2) a nolo contendere plea;

■ (3) a statement made during a proceeding on either of those pleas under

Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 11 or a comparable state procedure; or

■ (4) a statement made during plea discussions with an attorney for the prosecuting authority if the discussions did not result in a guilty plea or they resulted in a later-withdrawn guilty plea.

○ (b) Exceptions. The court may admit a statement described in Rule 410(a)(3) or

(4):

■ (1) in any proceeding in which another statement made during the same plea or plea discussions has been introduced, if in fairness the statements ought to be considered together; or

■ (2) in a criminal proceeding for perjury or false statement, if the defendant made the statement under oath, on the record, and with counsel present.

Evidence of Liability Insurance

● FRE 411. Liability Insurance

○ Evidence that a person was or was not insured against liability is not admissible to prove whether the person acted negligently or otherwise wrongfully. But the court may admit this evidence for another purpose, such as proving a witness’s bias or prejudice or proving agency, ownership, or control.

HEARSAY

Hearsay - Introduction

● FRE 801. Definitions.

○ (a) Statement. “Statement” means a person’s oral assertion, written assertion, or nonverbal conduct, if the person intended it as an assertion.

○ (b) Declarant. “Declarant” means the person who made the statement.

○ (c) Hearsay. “Hearsay” means a statement that:

■ (1) the declarant does not make while testifying at the current trial or hearing; and

■ (2) a party offers in evidence to prove the truth of the matter asserted in the statement.

● FRE 805. Hearsay within Hearsay.

○ Hearsay within hearsay is not excluded by the rule against hearsay if each part of the combined statements conforms with an exception to the rule.

● Notes on FRE 801.

○ Hearsay. An out-of-court statement offered to prove the truth of whatever it asserts. More specifically, an out-of-court statement is hearsay whenever the primary purpose of the statement is to prove the fact asserted in it, even though other secondary inferences are sought to be built around the primary inference as well.

■ Problems with Hearsay:

● Ambiguity

● Insincerity

● Erroneous memory

● Faulty perception

■ “Statement.” Three different types.

● 1. Statement that is action, and no verbal.

○ EX. Captain riding his ship with his family to demonstrate its seaworthiness.

● 2. Statement that is part action, part verbal.

○ EX. Customer rejecting a good as defective to show breach of warranty.

● 3. Statement that is verbal, and no action.

○ EX. Boss offers to hire applicant, to show that the applicant is competent for the job.

○ Note: The statement does not have to be an assertion, if an inference can be drawn from the statement. For instance, in the case of a boss hiring an applicant, the hiring is not an assertion that the applicant is competent, but that is an inference of the hiring that can be drawn later.

○ Estate of Murdock (Made-up Case)

■ I: Whether Mr. Murdock’s statement “I am still alive” spoken to a sheriff out of court when Mr. Murdock is found in the rubble of an airplane crash, and later testified to by the sheriff in court to prove that Mr. Murdock was alive at the time of the crash, is hearsay.

■ H: No. The reasoning for the hearsay rule -- including that parties have the right to confront their accusers, and that an out-of-court statement cannot be cross examined for reliability, credibility, etc. -- does not apply here. Arthur’s statement “I am alive” does not speak to his reliability or ambiguity or anything else; the statement shows he is alive, apart from if he was honest, reliable, or anything else. Arthur could have said “I am dead” and that would still show he was alive, because dead people don’t talk.

○ Tribe’s Triangle of Hearsay.

■ A (action or utterance) translates into B (belief of actor responsible for A); during this trip from A ⇒ B problems of ambiguity or insincerity arise.

■ B (belief of actor responsible for A) translates into C (conclusion to which

B points); during this trip from B ⇒ C problems of erroneous memory and faulty perception.

■ There are sometimes when A (action or utterance) translates straight into

C (conclusion to which the evidence is offered); this is not hearsay, see

Estate of Murdock example in textbook (the statement “I’m alive” goes straight to the conclusion that he was alive because dead people don’t speak; frankly, anything he said would have shown that he was alive; we

don’t care about all the “B” elements in the triangle, like how he perceives himself, or whether he’s telling the truth, etc.).

○ Subramaniam v. Public Prosecutor

■ I: Whether the trial court should have excluded the terrorist’s statements as hearsay, when Subramaniam is arrested for holding contraband, and at trial his defense is that he acted under duress of a terrorist group who made statements threatening to kill him.

■ H: No. Here, the terrorist statements were not being offered for their truth; rather, they were being offered to show their effect of duress on

Subramaniam. In fact, the terrorists could have been lying and the statements could still have an effect on Subramaniam; Subramaniam could then be cross-examined in court: the only issues of credibility, ambiguity, misperception, etc. are in Subramaniam’s testimony about the threats.

○ Vinyard v. Vinyard Funeral Homes

■ I: Whether the court can admit evidence that people complained to

Vinyard Funeral’s officers and employees that the sealed surface outside their business was slippery when wet, when plaintiff slipped and fell on the sealed surface in Vinyard Funeral’s dimly lit parking lot.

■ H: Yes, but only to show that Vinyard Funeral had knowledge of the slickness of the sealed surface, because that was one of the elements of the slip-and-fall claim. The evidence would have been improper as hearsay if it was offered only to prove the fact that the sealed area was slick; that fact would have to be proven by witnesses in court.

● R: Statements that would be hearsay when offered for their truth can be offered for other purposes, such as to show knowledge. In other words, when a statement gives rise to two inferences, one hearsay and the other not hearsay, only the non hearsay inference may be introduced in court (limiting instruction needed).

○ Johnson v. Misericordia Community Hospital

■ R: Documents can be hearsay.

● Note: Here, plaintiff sued a hospital for negligence in hiring Dr.

Salinsky because Salinsky botched plaintiff’s hip surgery. Plaintiff seeks to admit documents that Salinsky had been limited in his work at other hospitals because of incompetence, to use as evidence that the hospital was negligent in hiring Salinsky. The documents are hearsay, so they are permitted to show that the hospital had access to reports about Salinsky’s incompetence, not to prove Salinsky’s incompetence.

○ Ries Biologicals v. Bank of Santa Fe

■ R: “Independent Legal Significance.” A contract, agreement, or other instruments of independent legal significance can be entered into

evidence as not hearsay, because just the “speaking or signing of the words” creates rights and liabilities of the speaker.

● Note: In this case, the court held that an oral contract guaranteeing to pay for supply orders was not hearsay, because the relevance of the contract is not whether the contractors were lying, but whether the contract was made (i.e. contracts have legal significance admissible in court even if the persons are lying while making it).

○ Defamation. General rule is that words of slander, libel, and defamation are not hearsay, and therefore admissible even when made out of court, because it is not offered for the truth of what it states. Rather, defamation is offered for the non-truth of what it states.

■ EX. Aggie’s says out of court that Byron is an idiot. Byron sues. He may present Aggie’s out of court statement as not hearsay because he is not offering the statement for its truth, i.e. that he is an idiot. Rather, he is offering the statement to disprove it, i.e. to prove that he is not an idiot and she defamed him by stating it.

○ Fun-Damental Too v. Gemmy Industries

■ R: Consumer Surveys. Not hearsay, because they are not offered for the truth of what the consumers said in the hearsay.

● EX. Consumers are supposed to identify which of two lighters is a

Zippo lighter in a trademark infringement case. Some consumers will pick the generic brand, some will pick the Zippo brand. This evidence is not offered in a TM infringement case to prove its truth, i.e. that the lighters are or are not Zippo.

○ US v. Hernandez

■ Note: In a he-said-she-said battle trying to show that Hernandez is a drug smuggler, the government, in questioning DEA agent Saulnier (who was not witness to Hernandez drug smuggling) asked “What brought the attention of the DEA to Hernandez?” Saulnier replied “We received a referral by the US Customs as Hernandez being a drug smuggler.” The statement from the US Customs was inadmissible hearsay, because it was a statement made out of court, not by the witness, that offered to prove the truth of the matter asserted (that Hernandez was a drug smuggler). The government argues that the statement was only being offered to establish the state of mind of the DEA agent who heard the out-of-court statement, but the state of mind was irrelevant and was not an element of the crime or defense.

○ US v. Zenni

■ I: Whether implied assertions are hearsay, when -- while conducting a search of defendant Humphrey’s home with a search warrant -- officers answer the telephone and hear unknown callers give directions for

placing bets, and prosecution uses those calls as evidence to show that the callers believed the premises was used for betting operations.

■ H: No; FRE 803 removes implied assertions from definition of “statement,” consequently removing them from the definition of hearsay. Here, because the callers were not making an “assertion” that the telephone location was a betting operation by calling (the callers’ words merely

“implied” what the prosecution was seeking to prove), their statements while calling fall outside of the hearsay rule.

● R: Implied statements are admissible and not hearsay. See FRE

801(a), which says that a “statement” is an oral, written, or nonverbal “assertion.” Because declarations that imply things do not directly assert those things, they are not statements covered by the hearsay rule.

○ Wilson v. Clancy

■ I: Whether the affidavit of a witness (Dr. Hurney’s accountant), stating that she was never told by Dr. Hurney or his attorney Clancy that she needed to change titling of his assets so his will would effectively devise property to plaintiff, is admissible as evidence that Clancy committed malpractice by never giving Dr. Hurney that advice.

■ H: No; although silence is not hearsay, the evidence should be inadmissible because it has low probative value and high prejudicial risk under FRE 403. The silence of Dr. Hurney in not telling the witness (his accountant) to retitle his assets for his will could be due to lots of reasons; the court should exclude this evidence because it has low probative value to show Clancy’s malpractice, but high prejudicial value because the jury could infer a host of things from his silence (Dr. Hurney is now dead, so he cannot testify to his silence).

● R: Silence -- except sometimes intentional silence intended as an assertion when made -- is not hearsay. In other words, silence must be an assertion to be hearsay; most silence does not assert anything, and therefore has low probative value likely to be excluded under FRE 403.

○ Insanity.

○ US v. Jaramillo-Suarez

■ R: A document found at a location can be admitted to show the character and use of the place where it was found and not for the truth of any matters asserted within it. For instance, a drug sale ledger found in an apartment can be admitted to show that the apartment is owned by a drug-dealer, but the specific sales listed in the ledger cannot be admitted to show their truthfulness. Limiting instruction needed.

● Note: Here, drug ledgers found at an apartment frequented by the defendants could not be used to prove the truth of the statements made in the ledgers. However, they could be admitted as

circumstantial evidence that the apartment was being used for drug trafficking. The jury could consider that the pay/owe ledger was evidence of drug related activity, that was linked to an apartment, that was linked to defendant. Therefore the ledger was not excluded by hearsay rule.

○ Bridges v. State

■ R: Bridges Principle. A person’s out of court description of a location or thing, congruent with the actual physical appearance of that location or thing established by other evidence, is circumstantial evidence that that person has been to that location or seen that thing. Not excluded by hearsay because it is technically not offered for its truth to show what the place looked like, but rather to show the perspective of the witness matches the actual appearance of the place.

○ US v. Brown

■ I: Whether prosecution could admit evidence of an IRS agent Peacock, who testified that between 90% and 95% of tax returns prepared by defendant contained fraudulent material, in a case prosecuting defendant for tax fraud.

■ H: No; the evidence should be excluded as hearsay, because it was based on out of court conversations with taxpayers. Because Peacock got her “proof” that the tax returns contained fraudulent overstatements via out-of-court conversations with the taxpayers audited, the jury had no way to see if Peacock’s statement was true without seeing the difference between the fraudulent tax returns and the actual testimony of the taxpayers as to their actual tax statements, and the taxpayers were unable to be summoned to court to be cross examined.

○ City of Webster Grove v. Quick

■ R: Hearsay does not apply to what the in-court witness observed through sense or scientific instruments. Hearsay applies when evidence is obtained from an absent declarant whose perception, memory, and sincerity is the basis for the probative force of the evidence.

■ R: Hearsay does not apply to witnesses relying on mechanisms and machines like clocks, radar, scales, etc. to provide the witness with facts about a situation.

○ Animal Statements. When an animal acts (or talks, e.g. parrot) in a way that gives rise to an inference of something, the animal action or speaking is not hearsay.

○ Note: See recap of “hearsay” on page 17 of the lecture notes.

Hearsay - Testimony and Confrontation of a Witness

● Crawford v. Washington (Supreme Court)

○ I: Whether playing a recorded statement of a witness stating that her husband had stabbed a man during trial of the husband complied with the Sixth

Amendment's guarantee that “in all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right . . . to be confronted with the witnesses against him.”

○ H: No; where non-testimonial evidence is at issue, the Sixth Amendment does not demand confrontation; rather, a reliability analysis or hearsay exception may apply.

■ R: If it's not a testimonial, forget the Confrontation Clause analysis and only do the hearsay analysis.

■ R: If it IS a testimonial, do both the Confrontation Clause analysis and the hearsay tests. Under Confrontation Clause, defendant has to have had some opportunity to question/confront a witness (either before or during trial), and the witness has to be available if at all possible (even though the witness may be “unavailable” because they are out of jurisdiction, they may still be available because they can be brought into court).

● “Testimonial.” Applies at a minimum to prior testimony at a preliminary hearing, before a grand jury, or at a former trial, and to police interrogations.

● Davis v. Washington

○ I: Whether statements made to law enforcement personnel during a 911 call or at a crime scene are “testimonial” and thus subject to the requirements of the

Confrontation Clause pursuant to Crawford.

○ H: Depends: where statements are closer to contemporaneous statements, like her where there is an ongoing emergency, the statements are not “testimonial” in nature. Testimonial statements testify to past events.

● Michigan v. Bryant

○ I: Whether inquiries of wounded or dying victims concerning the perpetrator are non-testimonial if they objectively indicate that the purpose of the interrogation is to enable police assistance to meet an ongoing emergency.

○ H: Yes. Statements of wounded or dying victims are not testimonial because they involve an ongoing emergency.

● Melendez Diaz v. Massachusetts

○ R: Forensic laboratory reports are testimonial for purposes of the Confrontation

Clause.

● Williams v. Illinois

○ R: Plurality. When prosecution calls a witness to the stand to testify about a DNA report that the witness did not prepare, the defense cannot invoke the Sixth

Amendment to demand cross-examination of the person who actually prepared the DNA report.

■ Note: Dissent says that this allows prosecution to bypass the protections of the Sixth Amendment.

HEARSAY EXEMPTIONS

Exemption - Statements of Party Opponents

● FRE 801(d)(2). An Opposing Party’s Statement. The statement is offered against an opposing party and:

○ (A) was made by the party in an individual or representative capacity;

○ (B) is one the party manifested that it adopted or believed to be true;

○ (C) was made by a person whom the party authorized to make a statement on the subject;

○ (D) was made by the party’s agent or employee on a matter within the scope of that relationship and while it existed; or

○ (E) was made by the party’s coconspirator during and in furtherance of the conspiracy.

○ The statement must be considered but does not by itself establish the declarant’s authority under (C); the existence or scope of the relationship under (D); or the existence of the conspiracy or participation in it under (E).

● Note: Under FRE 602, witnesses usually need personal knowledge before their statements are admissible. However, SOPOs are admissible regardless of personal knowledge.

● Reed v. McCord

○ I: Whether the following statement is admissible as SOPO in a wrongful death case: defendant's statements about the circumstances and cause of plaintiff’s fatal accident made to the coroner, even though defendant had not seen (did not have “personal knowledge” of) the accident.

○ H: Yes. Because defendant made the statements of the circumstances and cause of plaintiff’s injury as though defendant had actually seen the incident, defendant must “own” the statement under the SOPO exception. It does not matter that the defendant did not know what he was talking about or did not have personal knowledge of the incident.

■ R: FRE 801(d)(2)(B).

■ R: SOPOs do not need to be against the interest of the party opponent at

● US v. Hoosier. the time they are spoken.

○ I: Whether the following statement is admissible as SOPO against defendant in a bank robbery case: a girlfriend of a defendant, in a private place in the presence of the defendant, said to a witness “we have sacks of money in our hotel room”, and the witness later testified to this statement in court to prove that defendant is a bank robber.

○ H: Yes. An opposing party can “adopt or acquiesce” to a statement of another by agreeing with it. When silence is relied on as agreement with a statement, the theory is that the person would, under the circumstances, protest the statement made in his presence, if untrue. Here, under the total circumstances, the probable human response to the girlfriend’s statement would be to deny it if untrue; therefore, because defendant did not deny the statement, his silence was

“adoption” of it.

■ R: FRE 801(d)(2)(B).

■ R: Silence can constitute “adoption” of a statement for purposes of

SOPO. Note: Does not always apply in criminal cases because of the risk of self-incrimination.

● State v. Carlson

○ I: Whether the following “statement” is admissible as SOPO: defendant’s nonverbal reaction of “hanging his head” when his wife implicated him with drug ownership and usage in front of police.

○ H: No. Insufficient evidence. Based on the circumstances of the case and the findings of the trial judge, defendant’s nonverbal reaction is too ambiguous to be reasonably deemed sufficient to establish that one result is more probably correct

(e.g. confusion, bewilderment, refusal, “I don’t know,” dismay, resignment, denial).

■ R: FRE 801(d)(2)(B).

■ R: The intent to adopt a statement under FRE 801(d)(2)(B) is a preliminary fact question for the judge to decide by a preponderance of the evidence under FRE 104(a).

● Mahlandt v. Wild Canid Survival and Research Center

○ I: Whether the following statements are admissible by plaintiff as SOPO evidence that a wolf bit their child: [1] a note written by individual defendant Poos, an employee of corporate defendant Wild Canid, to one of Wild Canid’s executives saying that one of their wolves bit a child, even though Poos did not personally witness it; [2] the minutes of a meeting of corporate defendant Wild Canid’s board of directors, discussing at length the legal ramifications of their wolf biting the child.

○ H: [1] Yes. Even though Poos had no knowledge of the wolf actually biting the child, he took ownership of the statement by writing it down. The statement is admissible against Poos as an individual defendant because he made it. The statement is also admissible against Wild Canid under FRE 801(d)(2)(D) because Poos made the statement while employed by them, and the statement concerned a matter within the scope of his employment as the wolf caretaker. [2]

Yes. The board had authority as the primary officers of Wild Canid to speak for it under FRE 801(d)(2)(C). The statements are admissible against Wild Canid.

However, the statements are not admissible against Poos because the board of directors is not the agent or employee of Poos and does not have authority to speak for him (note: Poos was not present at the meeting, so he could not adopt the board’s statements).

■ R: FRE 801(d)(2)(D).

■ R: FRE 801(d)(2)(C).

● Sabel v. Mead Johnson

○ I: Whether the following statements are admissible by plaintiff as SOPO evidence that defendant manufacturer’s drug causes priapism: a tape of a meeting convened by the medical manufacturer and attended by outside medical experts who were called to discuss the drug.

○ H: No (close call). The outside medical experts were not “agents” under FRE

801(d)(2)(D). The analysis is whether they had authority to speak for the manufacturer: here, the manufacturer here did not adopt their statements, did not request or receive a final report, and controlled the information given to the consultants. Also, the experts spoke off-the-cuff rather than scripted by the company.

■ R: FRE 801(d)(2)(D).

Exemption - Statements of Co-Conspirators

● FRE 801(d)(2)(E). An Opposing Party’s Statement. The statement is offered against an opposing party and: . . . (E) was made by the party’s coconspirator during and in furtherance of the conspiracy.

● US v. Goldberg

○ R: A late-joining conspirator takes the conspiracy as he finds it; “conspiracy is like a train.” Therefore, statements made by the conspirators before defendant joined the conspiracy can be used against the defendant under the co-conspirator exception.

○ R: Three things have to be found to operate the co-conspirator exception:

■ (1) Existence of a conspiracy.

■ (2) Statement is made during the existence of the conspiracy.

■ (3) the statement must be made in furtherance of the conspiracy.

● US v. Doerr

○ I: Whether the following statements were made “in the furtherance of a conspiracy” to run a prostitution ring at a massage parlor and strip club, such that they are admissible against conspirators in the prostitution ring: [1] a statement by a non-defendant saying “the red curtain in the patio area is ridiculous because it is asking for problems from the police,” and [2] a statement by defendant’s half brother saying to defendant “I can’t believe you don’t know what’s going on.”

○ H: [1] No. This statement was not made in furtherance of the conspiracy, because although the declarant was a frequent customer and potential investor in the strip club, his statement was merely a narrative discussion of a past event rather than advice on how to further the conspiracy. [2] No. This statement was merely mocking the naive half-brother; it in no way furthered the conspiracy.

● Bourjaily v. US

○ I: Whether the court may determine under FRE 104(a) that independent evidence exists showing that the conspiracy exists and the defendant and declarant are members of the conspiracy.

○ H: Yes. Before FRE 801(d)(2)(E) can kick in, there must be evidence that a conspiracy existed and declarant and defendant are members, such that the court can determine whether the declarant’s statements were in furtherance of the conspiracy. The court finds this under FRE 104(a) and preponderance of all the evidence available, both testimonial and independent.

■ R: Bootstrapping Rule. The court under FRE 104(a) can consider a declarant’s statements about an alleged conspiracy as evidence of the

existence of the conspiracy (coupled with independent evidence and other testimonial evidence).

■ R: Parties only have to be active in a de facto conspiracy for this exception to apply; they do not have to be convicted of a conspiracy.

Exemption - Declarant-Witness’s Prior Statement

● FRE 801(d)(1). A statement that meets the following conditions is not hearsay: The declarant testifies and is subject to cross-examination about a prior statement, and the statement:

○ (A) is inconsistent with the declarant’s testimony and was given under penalty of perjury at a trial, hearing, or other proceeding or in a deposition;

○ (B) is consistent with the declarant’s testimony and is offered:

■ (i) to rebut an express or implied charge that the declarant recently fabricated it or acted from a recent improper influence or motive in so testifying; or

■ (ii) to rehabilitate the declarant's credibility as a witness when attacked on another ground; or

○ (C) identifies a person as someone the declarant perceived earlier.

EXCEPTIONS TO HEARSAY

Exception - Spontaneous and Contemporaneous Exclamations

● FRE 803(1). Present Sense Impression. A statement describing or explaining an event or condition, made while or immediately after the declarant perceived it.

● FRE 803(2). Excited Utterance. A statement relating to a startling event or condition, made while the declarant was under the stress of excitement that it caused.

○ Note: “Stress” of excitement. The startling event could have already occurred, but it may still be an excited utterance if the declarant is still under the startled impression of the event.

● Photo Identification. When a witness at trial is shown a picture of a “startling event” (e.g. a crime scene, their excited response in court is usually not an “excited utterance” under

FRE 803(2) because it was not connected directly to the actual occurrence of the event, just the picture of it.

● Truck Insurance Exchange v. Michling

○ I: Whether the following statement is admissible as an excited utterance in a wrongful death suit: the wife of the decedent testifies that her husband was pale and stumbling around when he returned home, and he told her before he died that “he hit his head on the bulldozer at work, because the iron bar across the seat slipped.”

○ H: No. The statement offered by the wife is the only evidence that the husband was killed by the bulldozer bar, so it is hearsay because it is offered to prove its own truth. However, this also means that the utterance was not definitely made in connection with a startling circumstance, because there is no proof the startling circumstance occured other than the statement.

■ FRE 803(2). Excited Utterance. Three elements: (1) An occurrence startling enough to produce nervous excitement occurs (verified by independent evidence); (2) an utterance is made before there was time to contrive a statement, although not strictly contemporaneous with the exciting cause; and (3) the utterance relates to the startling occurrence.

■ R: Wade v. Texas Employers. The startling occurrence giving rise to the excited utterance cannot be solely proven by the excited utterance; there needs to be independent evidence of a startling circumstance to support the excited utterance.

● Lira v. Albert Einstein Medical Center

○ I: Whether the following statement is admissible as [1] an excited utterance or [2] a present sense impression in a medical malpractice suit: a doctor, examining plaintiff’s wife, looks at her throat and exclaims “who’s the butcher who did this?”

○ H: [1] No. The statement was hearsay, and did not fall under the excited utterance exception because the doctor was an ENT who would not have been startled by a botched throat abnormality such as to be “overcome with emotion” and state an excited utterance. [2] No. The statement also did not fall under the present sense impression exception because his statement was not a sensual response or reflex to the situation, but rather a statement made of medical opinion based on training and experience.

■ R: FRE 803(1).

■ R: FRE 803(2).

● State v. Jones

○ I: Whether the following statements are admissible as a present sense impression in a case suing a police officer for sexual assault:

■ Plaintiff claims that a trooper sexually assaulted her, then sped off without giving her a ticket at a high rate of speed with his taillights off, and that she gave chase in her car. In support of this story, she seeks to admit two radio transmissions of truckers picked up by a police officer which state, respectively, [1] “look at the [trooper] southbound with no lights on at a high rate of speed” and [2] “look at that little car trying to catch up with him.” At trial, the officer who over overheard the radio transmissions paraphrases the statements while reiterating them to the jury.

○ H: Yes, the statements were made contemporaneous and would be admissible; here, however, the statements were paraphrased in narrative form by a testifying officer, which causes the case to be remanded.

● Davis v. Washington

○ H: Contemporaneous statements, or statements made contemporaneously with an ongoing investigation, are not “testimonial” under the Confrontation Clause and Crawford.

Exception - State of Mind

● FRE 803(3). Then-existing Mental, Emotional, or Physical Condition.

○ A statement of the declarant’s then-existing state of mind (such as motive, intent, or plan) or emotional, sensory, or physical condition (such as mental feeling, pain, or bodily health), but not including a statement of memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed unless it relates to the validity or terms of the declarant’s will.

● Examples:

○ Upon seeing Buzzy in ball park, Declarant said “I believe that’s the man I saw running out of the bank.” Statement is offered at trial to prove Buzzy robbed the bank. What result?

■ Hearsay. State of mind exception does not apply, because the exception cannot include statements of “memory or belief to prove the fact remembered or believed.”

○ Declarant wrote to his older cousin “please talk to my daughter Fuzzy, she’s fallen in love with day trading and is going to lose all her money.” Statement is offered at trial to show the older cousin was mentally competent at the time. What result?

■ Implicit assertion, hearsay. State of mind exception applies.

● Adkins v. Brett

○ I: Whether the following statements show the “state of mind” of the wife in an alienation of affection case: wife told plaintiff that she had gone riding in the car with defendant, had dinner with him, received flowers from him, and that he was able to give her a good time, and further that plaintiff was not able to give her a good time.

○ H: Likely yes, but remanded because an improper jury instruction was given in this case. Where the “state of mind” exception is used, a good instruction to the jury must be given so they only use the hearsay evidence to prove state of mind.

■ R: This “state of mind” exception to the hearsay rule should always be paired with an instruction to the jury of the court that the evidence can only be used to prove state of mind, not to prove anything else.

■ Note: The actual case is more nuanced. In the actual case, the plaintiff tried to introduce statements from his wife about what a great time she had with defendant as evidence that she didn’t like plaintiff; these are not relevant to showing that, but in the ‘50s when this case was decided it might have been a different outcome.

● Mutual Life Insurance v. Hillmon

○ I: Whether the following out-of-court letters are admissible for the purpose of showing Walter’s intention of going to Crooked Creek in a case where defendants seek to show that a body found in Crooked Creek is Walter: a letter from Walter to his sister and fiance expressing his intention to go with another man Hillmon to Crooked Creek.

○ H: Yes. However, the letters are only admissible for showing his intention (his state of mind intending to go to Crooked Creek), not to prove that the body in the

creek was actually Walter, or that Walter actually went to Crooked Creek. The judge must give a limiting instruction as to the usage of this evidence.

● Shepard v. US

○ I: Whether the following evidence is admissible under the “state of mind” exception as tending to prove that Dr. Shepard murdered Ms. Shepard with poison: Ms. Shepard asked her nurse to get a bottle of whiskey from the cabinet, told her nurse that she had drank that liquor right before collapsing, and then stated “Dr. Shepard has poisoned me.”

○ H: No. The statement of Ms. Shepard is not admissible under the “state of mind” exception because it does not show her present feeling, only the action of another party.

■ Note: This statement may be admissible under “state of mind” for the purpose of proving that she was not suicidal.

● US v. Pheaster

○ I: Whether the following evidence is admissible under the “state of mind” exception as tending to prove that a meeting occurred between a victim and defendant: victim, while with his friends, told them he was going to the parking lot to meet defendant to buy marijuana.

○ H: Yes. The victim’s statements show his “intention” to go to the parking lot to meet the defendant. His statements are subject to a limiting instruction.

■ Note: Slightly different than Hillmon’s “intention” doctrine, because here the declarant’s statement of intention necessarily requires the action of one or more others if it is to be carried out (i.e. the meeting could not occur if the defendant did not show up).

● Zippo Manufacturing v. Rogers Imports

○ I: Whether following evidence is admissible under the “state of mind” exception to hearsay when offered to prove consumer confusion in a trademark infringement case: Plaintiff Zippo conducted a “consumer confusion” survey by showing survey participants one of its lighters and the allegedly infringing lighter, and the participants made out-of-court statements about which one they thought was

Zippo’s lighter.

○ H: No need to use the state of mind exception, because the statements are not hearsay; survey statements are not hearsay under FRE 801 because they are not offered to prove their truthfulness.

Exception - Former Testimony

● FRE 804(b)(1). The following are not excluded by the rule against hearsay if the declarant is unavailable as a witness :

○ (1) Former Testimony. Testimony that: