(1)The strategic use of questioning

Here are some key ideas from the research into the role of questioning as part of Assessment

for Learning (formative assessment):

Idea No. 1

In terms of student behaviour, strategic questioning encourages students to:

listen actively

speak

take turns

be actively involved with learning.

If the classroom culture does not encourage 'hands up', but rather emphasises that everyone is

expected to think and be ready to answer any question, students are more likely to be involved

with the lesson.

Likewise, if the classroom culture encourages the asking of questions and makes it okay to give

a wrong answer, then students will be more likely to offer answers.

Idea No. 2

The asking of questions is a deliberate, planned activity.

Identify the learning intention and plan related questions to target knowledge, understanding

or the teaching and learning strategies.

Plan for more open questions than closed questions, understanding that open questions

provide more opportunities for the teacher to understand the thinking behind a response and

more opportunities for the students to demonstrate their understanding.

Plan for questions that pose appropriate cognitive demands, not only in respect of the age and

development of the student but also in terms of where the questions occur in the unit or

lesson. This means asking knowledge and comprehension questions about new material prior

to questions of analysis and evaluation.

Idea No. 3

Provide students with time to think after asking a question.

This means accepting a pause or silence as an integral part of questioning during class. More

demanding, open-ended questions pose cognitive challenges. Students need time to reason

and consider their answers. Research (Rowe 1972) strongly suggests that, where there is a

lapse of time between question and answer, answers dramatically increase in quality. Where

teachers wait for student responses, more students participate in answering, responses are

longer and more confident, and students comment, respond to and thus build upon each

other's answers.

Idea No. 4

A critical factor in enhancing the strategic effectiveness of questions is teacher receptiveness.

The teacher's positive response to both good and wrong answers is essential.

o

o

o

A receptive, listening attitude on the part of the teacher is conveyed through:

facial expression

body language

verbal responses.

Responses to wrong answers can include:

o

o

o

o

o

the teacher rephrasing the original question

'Let me put it another way…'

a request for clarification

'What do you mean when you say …?'

a request for specific examples

'How would this work?'

'Can you give me an example of this?'

a request for rephrasing

'Can you put it another way?'

Idea No. 5

The strategic effectiveness of questioning is further enhanced by:

moving around the room to make sure questions are more likely to be evenly distributed. Other

ways of making sure questions are evenly distributed include allowing students to talk to each

other about a question, asking everyone to write down an answer and then reading out a

selected few, or giving students a choice of possible answers and having a vote on the correct

option. All of these tactics increase student participation.

posing one question at a time. Asking a string of questions, particularly without any pause, is

confusing.

providing prompt questions such as

'Why do you think that?', 'Can you tell me more about …?' or 'Is it possible that ...?'

posing fewer, well chosen questions is more strategic as an assessment for learning strategy.

Idea No. 6

When planning, teachers need to decide the purpose of their questions and then select the

most appropriate type of questions for that purpose. Bloom's taxonomy can assist with the

framing of questions that pose different cognitive demands.

Knowledge and comprehension are assessed using closed questions that pose lower cognitive

demands because they rely largely on memory and have one correct answer.

Application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation are assessed using open questions that pose

higher cognitive demands, lead students to think for themselves and have several correct

answers.

Both closed and open questions are important Assessment for Learning tools.

Closed questions are useful for establishing the core material of a unit, while open questions

advance students into manipulating, extending and transforming this material.

Reliance only on closed questions, however, will limit the amount of information that teachers

are likely to learn about their students, and will fail to make a range of cognitive demands on

the students.

Idea No. 7

To phrase strategic and stimulating questions, teachers could make use of a number of other

tools besides Bloom's. Some of these are:

De Bono's Six thinking hats

The Six thinking hats is a strategy that encourages students to look at a topic or problem or idea

from more than one perspective. Each hat represents a different kind of thinking and therefore

different kinds of questions.

Wiederhold's Question matrix

The Question matrix contains 36 question starters asking what, where, when, which, who, why

and how. These questions are asked in present, past and future tenses, ranging from simple

recall through to predictions and imagination or single questions depending on the task.

Thinker's keys

Thinker's keys is a strategy to develop creative and critical thinking designed by Tony Ryan, a

consultant for Gifted and Talented Programs in Queensland. Each of the 20 keys is a different

question which challenges the reader to compose his or her own questions and come up with

responses.

(2)Peer feedback

Research suggests that peer feedback is most effective when students feel comfortable with

each other and supported by their peers, respect each other's opinions and feel able to take

risks and make mistakes.

Teachers create an environment in which risk-taking is accepted and there are no 'put-downs'

from other students when mistakes are made. They always intervene when 'put-downs' do

occur, making certain that students understand there is no place for this in a learning

classroom.

Teachers deliberately conduct activities that serve to develop an atmosphere of cooperation,

support and trust and explicitly teach students how to give feedback and how to receive

feedback.

They model the process in a very explicit way, articulating for students what they are doing and

drawing attention to the language they are using. Role-play is useful here, followed by

a debrief.

The physical configuration of the classroom should lend itself to students working together in

pairs and groups, which in turn facilitates exchange of information and peer feedback. Clusters

of tables or desks make more sense than lines or semicircles, although there needs to be

enough flexibility for desks or tables to be quickly rearranged to allow for whole-class activities

as well as group or paired activities.

With older students, a basic understanding of learning styles can assist in helping students to

understand that not everyone learns in the same way, and that different ways of learning are

more or less effective for different people.

Discussion with students about learning styles also encourages the development of

metacognition in relation to their own learning styles and preferences.

Strategies to enhance peer feedback

Some strategies are particularly suited to younger students, where often the names that

teachers have for these strategies provide a 'shorthand' way of communicating to students that

they wish them to provide peer feedback.

For example:

Two stars and a wish

Plus, minus and what's next?

Warm and cool feedback

Traffic lights

In addition, teachers of all levels can also use the following strategies:

Using models or exemplars

De Bono's Thinking hats

Using a rubric

For younger students, it is easier and more effective to encourage oral rather than written

feedback.

Two stars and a wish

Students identify two positive aspects of the work of a peer and then express a wish about

what the peer might do next time in order to improve another aspect of the work. 'I want to

give you a star for the start of your story and a star for the way you described the house. I wish

that you will tell us more about Billy.'

Teachers model this strategy several times, using samples of student work, before asking the

students to use the strategy in pairs on their own. They check the process and ask pairs who

have implemented the strategy successfully to demonstrate it to the whole group.

Plus, minus and what's next?

Students comment on what was done well in relation to the success criteria, and also on what

could be done better. This strategy may be better used after the students have become adept

at using Two stars and a wish. This strategy can also be used as part of self-assessment, where

students use 'What's next?' to set a personal learning target.

Warm and cool feedback

When students comment on the positive aspects of a peer's work, they are said to be giving

warm feedback, and when they identify areas that need improvement, they are providing cool

feedback. They provide hints on 'how to raise the temperature' when they give advice about

how their peer could improve their work.

Traffic lights

Students green-light (using a green highlighter on the margin of the work) the work of their

peer to indicate where the success criteria have been achieved, or amber-light where

improvement is needed.

This strategy is best used on a work-in-progress, although it could also be used, with coloured

sticky notes, to provide feedback on a final piece of work. The suggestions for improvement

would then relate to the next occasion on which the students undertook work which required

similar skills - writing or number skills, for example.

Using models or exemplars

Teachers demonstrate for students how they can match the work of a peer to an exemplar

which most closely resembles its qualities. For example, for young students exemplars of

handwriting which reflect a range of qualities (letters on/off line, no spaces/spaces between

words, straight/crooked letters, mixture of upper- and lower-case letters etc.) can be displayed

in the classroom and students asked to match the handwriting of the peer with the appropriate

exemplar.

Students explain to the peer why they have selected this particular exemplar and, using other

exemplars, explain what the peer needs to do in order to improve his/her handwriting.

Exemplars of various products (written and 3-D) can be displayed in the classroom for use both

by individuals to self-assess and also by peers to provide feedback. If there is concern that

providing a model will lead to copying or stifle imagination and creativity, the teacher might

consider providing exemplars of parts of the product - for example, an effective introduction or

an interesting use of media in an artwork.

When employing exemplars as a self-assessment strategy, students use the exemplars to help

them articulate what changes they need to make to their own work in order to achieve the

success criteria.

De Bono's Thinking hats

Because the Thinking hats encourage thinking from different perspectives, they can be used to

focus students' feedback to their peers. Again, teachers model the use of the Thinking hats and

train students in their use before asking them to use the hats as one of the peer feedback

strategies.

The Yellow hat, for instance, encourages students to think about the 'good points' and to ask

themselves questions such as 'Why will this work?' The Black hat urges caution and evaluation:

'Is this true? What are the weaknesses?' while the Green hat encourages creative thinking: 'Is

there another way of doing this?' 'What would be better?' 'How else can this be done?'

Giving different students different hats can make peer feedback more focused and manageable

for younger students. That way, each individual doesn't have to consider every aspect of the

peer feedback but can concentrate on just one.

Using a rubric

For larger assessment activities conducted over a period of time, the rubric, which has been

negotiated with students at the beginning of the task, can be used as the basis for paired

discussions about progress. If students are very clear about the qualities of work implied by the

various levels of performance described on a rubric, they can provide useful feedback to their

peers.

If rubrics are to be (a) designed so they do capture the difference between levels of

performance and (b) used effectively by students not only as a peer feedback tool but also as a

self-assessment tool, then students need explicit teaching so they understand the differences

between, for example, work which lists benefits as opposed to work which describes those

benefits or explains them or evaluates them. An understanding of the language used by the

rubric is essential.

(3)Student self-assessment

Student self-assessment is now regarded as vital to success at school. Black and Wiliam (1998)

put it like this:

… self-assessment by pupils, far from being a luxury, is in fact an essential component of

formative assessment.

The implementation of student self-assessment in the classroom does not ignore the role of the

teacher.

The very important role of the teacher involves:

sharing with students the success criteria for each assessment activity

ensuring that students understand the success criteria

explicitly teaching students how to apply those criteria to their own work

providing students with feedback to help them improve; and

helping students to set learning targets to achieve that improvement.

Students who use self-assessment:

recognise that learning is associated with a very positive kind of difficulty, which increases

motivation rather than destroying it

experience an increase in self-esteem

experience an improvement in their learning because they come to know how they learn rather

than just what they learn.

Teachers who encourage students to self-assess:

see the responsibility for learning shifting from them to their students

recognise an increase in student motivation and enthusiasm for learning and a corresponding

decrease in behavioural problems

are able to use feedback from their students about how they learn to shape lessons to

individual and group needs rather than teaching to the mythical class as whole

Strategies to enhance student self-assessment

Reflection activities

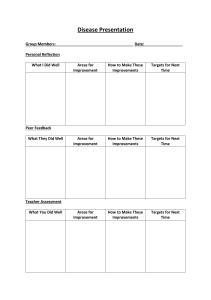

Teachers often use proformae to encourage students to reflect on their learning experience.

While these are convenient and provide a record of student thinking, they can become an

activity devoid of any real thinking. Oral reflection, whether as a whole class or group within the

class, might sometimes be more useful. Alternatively, teachers could devote some time to

questioning students about what they have recorded on their proformae and asking them for

explanations.

Student-led and three-way conferences

Use of rubrics

Use of graphic organisers

Target setting

Time management

Student-led and three-way conferences

Student-led conferences in which students present their learning to their teacher and parents

are an opportunity for students to formally reflect on the learning that has taken place over a

period of time. This reflection occurs as students prepare for the conference, as well as during

the conference itself when they show and explain to their parents what they have learned.

Usually the evidence they produce is in the form of a portfolio, which students have prepared

according to provided guidelines.

The student, with teacher guidance, is the one who selects the work.

The teacher makes sure the students understand the purpose of the portfolio - that is, that:

it represents some but not all the work they have done in class over a period of time

it demonstrates both strengths and weaknesses

it will be used to help them reflect on what they have learned and what they still need to learn

it will help them to state clear goals for future learning, based on the areas where they need to

make more progress.

Use of rubrics

Rubrics are a valuable tool for self-assessment. Because rubrics not only list the success criteria

but also provide descriptions of levels of performance, students are able to use them to

monitor and evaluate their progress during an assessment task or activity.

Teachers make certain that students have copies of the rubric prior to commencing the

assessment activity and understand the terminology used in the rubric. If necessary, they

provide students with models or exemplars to illustrate relevant aspects of the activity.

As they work to complete the activity, students monitor their work to ensure that it

demonstrates the required skills, knowledge or understanding. They reflect on their progress

and evaluate what they need to do if they wish to improve their performance.

Use of graphic organisers

A graphic organiser organises facts, concepts, ideas or terms in a visual or diagrammatic way so

that the relationship between the individual items is made clearer.

The value of graphic organisers in terms of student self-assessment lies in their ability to assist

thinking and make it visible for both the student and the teacher. For example, empty spaces in

graphic organisers reveal gaps in the student's knowledge or thinking. They indicate

immediately what still needs to be discovered or learned. If graphic organisers are used in

preparation for a written response, they can show where more information or further

argument is necessary, and when students are asked to explain their use of the graphic

organiser there is an opportunity for metacognitive development because they must explain

their thought processes. ('Why did you put that piece of information here?')

If students are taught how to use graphic organisers, they can learn to select those which are

compatible with their learning styles. Some learners, for instance, will gravitate towards

organisers which use words to elucidate links, such as tables of various kinds; others will be

happier with symbols such as arrows and boxes of various meaningful shapes.

Setting learning targets

The setting of learning targets, or goal-setting, is an intrinsic part of the iterative nature of selfassessment. Student self-assessment begins with setting learning targets, proceeds through the

production of work that aims to achieve those targets, to the assessment of the work to see if it

does in fact meet the targets and then, finally, to the setting of new targets or revising ones

that were not achieved.

Diagrammatically, the process looks like this:

Ideally, students will increasingly assume responsibility for the setting of their learning targets

and also for the monitoring or tracking of those targets. In practice, of course, students' ability

to do this will vary, and teacher assistance will be more important to some students than

others. The provision of suitable 'tracking' sheets is an obvious way for teachers to assist all

students.

As with other aspects of instruction, the use of modelling and explicit teaching is of relevance

here. Teachers commonly use the SMART acronym as a way of guiding students in the design of

a learning target. In this acronym:

S = Specific

M = Measurable

A = Achievable or Attainable

R = Relevant

T = Time-bound

The SMART method of setting learning targets:

Specific

The learning target must be specific rather than general: 'I will include a topic sentence in each

paragraph' rather than 'I will improve my paragraphing.'

Measurable

It must be possible to know whether the learning target has been accomplished, so there needs

to be some way of measuring this. 'I will learn my 7 times table', for instance, could be

measured by 'Being able to recite to my teacher/parent/peer the table X times without making

mistakes.'

Achievable

The achievement of the learning target must be something the student is capable of attaining.

Where the prospect of achievement seems daunting, the learning target can be broken down

into a series of steps so that the student has the prospect of experiencing success. For example,

instead of a learning target that states 'I will use correct spelling', it is better to concentrate on

the use of individual spelling strategies so that, over time, the student builds up a repertoire of

strategies designed to achieve the aim of improving his or her ability to spell correctly.

The setting of unachievable learning targets will inevitably lead to lack of motivation and low

self-esteem.

Relevant

The learning target needs to be significant and relevant to the student's present learning. If

students are left to set learning targets without any guidance, at least initially there is a danger

that such targets will be less relevant than if they are set in the context of understanding 'What

I know or can do now/ what I still need to know or be able to do/ how I can go about making

that improvement'.

Time-bound

Students should specify when they aim to achieve the target. Time-bound learning targets are

easier to evaluate and track than those which have no particular time period attached to their

achievement.

Time management

Students' ability to manage and organise their own time in order to complete set tasks is a

crucial aspect of self-assessment. Schools recognise this when they institute a variety of

structures to support students developing independence in this area; the student diary is one

example.

In the case of extended projects, middle-year students can be assisted to manage their time if

teachers 'chunk' the work into discrete sub-tasks. For instance, students who are researching

information prior to making a class or group presentation can be advised that the task

comprises the following sub-tasks, each of which will have a certain period of time allotted to it.

Decide on research topic

Draw up list of possible resources

Assign group roles

Conduct research

Develop presentation

Rehearse presentation

Make presentation

This information can be supported visually by Gantt chart which can be displayed in the

classroom and used by both teacher and students to monitor progress.

For older students who have experience of Gantt charts, the production of such a chart and its

submission to the teacher for feedback could be made a mandatory first step when they are

beginning an extended task.

(4)The formative use of summative assessment

The need to make formative use of summative assessment is emphasised by research eg Harlen

and Deakin Crick (2002) which has identified the negative impact of summative assessment on

the self-esteem of low achievers.

An important aspect of making formative use of summative assessment is the use of effective

teacher feedback.

Cited (Hattie 1999) as one of the most effective ways teachers can improve student

performance, teacher feedback that occurs both during the development of an assessment

activity, and after its completion, is a powerful way of ensuring that students learn as a result of

summative assessment.

The role of student self-assessment is also an important aspect of making formative use of

summative assessment. When students exercise responsibility for their own learning, they are

demonstrating an awareness of themselves as learners, and self-esteem and motivation have

been shown to increase.

Strategies to promote the formative use of tests

Making formative use of national tests

Making formative use of national tests has two aspects: preparing students for the test and

making use of the test results.

Preparing students for the test involves ensuring that students have the necessary skills,

knowledge and understanding to cope with the demands of the test, and also ensuring their

familiarity with the testing genre. This involves an understanding of the structure and language

features of the test (the use of bold, italics, layout, recognition of types of test items, key

vocabulary), strategies for tackling particular types of questions (eg multiple choice) and

skimming and scanning.

Making use of results from national testing

Look first at the skills, knowledge and understanding that the individual test items purport to be

testing, and then examine the statistical data which summarises student performance.

Identified trends in performance - for example, evidence that a significant number of students

experience difficulty making inferences - can be used in a formative way to determine future

teaching.

Making formative use of classroom tests

How much formative use can be made of a written test depends on the quality of the test

design. Where a test makes a number of different and escalating cognitive demands of

students, the information thus gained about student skills, knowledge and understanding will

be more sophisticated.

Before the test

Consider the timing. Tests administered at the beginning of a unit, for example, can be an

accurate way of determining exactly what students already know and are able to do. This

information is then used to shape the approach to the teaching of the topic and, in particular,

to identify a starting point for further learning.

A test mid-way through a unit is another way tests can be used by both students and teachers

for assessment for learning purposes. Gaps in understanding are revealed in a timely fashion,

allowing teachers to focus teaching to fit student needs and provide students with the

opportunity to act on feedback to improve their performance.

Preparing for a test by using Traffic Lights

In this strategy teachers provide students with a list of the skills, knowledge and understandings

the test will focus on, and students work through the list, identifying each aspect as follows:

‘I can explain this aspect to someone else.’ (green light)

‘I think I understand this aspect but I’d have difficulty explaining it to someone else.’ (amber

light)

‘I don’t understand this aspect.’ (red light)

The resulting record gives students a focus for their revision.

Writing the questions – or even the whole test

Asking students to design an appropriate question provides them and the teacher with an

opportunity to evaluate their understanding of the skills, knowledge and understanding that

are involved.

Designing the entire test (within provided guidelines which indicate the number and variety of

question types) involves more learning than simply responding to a teacher-generated test.

After the test

After the test, there are many opportunities for a formative approach.

Instead of simply handing back the marked tests to students and then going through the test to

explain the required answers, teachers can use strategies which encourage further

reinforcement and learning.

Before the test is marked and returned to students, the teacher divides up the test and allots

different sections or questions to groups of students. The role of the students is to agree on a

response to each of the questions and how marks should be allotted. Groups then share their

work with the class.

Teachers identify those questions which caused the most difficulty for students, and then go

over the answers to these with the class before they return the completed tests to the

students.

Teachers identify the ten toughest questions (or however many are relevant given the design of

the test). They ask students to review those questions in pairs to confirm what they believe

should be the correct answers. They then confirm their answers with another pair before

checking with the teacher. (This strategy was suggested by the Alberta Assessment

Consortium.)

When students spend a significant period of time working on an extended assessment task, it is

important that the task has been designed so it is likely to yield a significant amount of

information about student performance.

Ask these questions:

Will the design of the task allow students the opportunity to demonstrate their achievement of

the skills, knowledge and understanding that will be the focus of the unit?

Is there any opportunity to achieve those skills, knowledge and understanding at a number of

different levels?

Are the success criteria explicit and will they be shared with the students before the unit

begins?

Is the form or forms of the assessment product (oral, written, performance, other) consistent

with the skills, knowledge and understanding that will be the focus of the unit? (For example, if

students are asked to produce evidence of their learning in the form of a brochure or website

or 3-D model, will they be provided with models and specifically taught the structure and

features of those forms?)