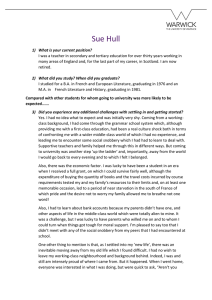

102 DIANA DIZEREGA WALL Examining Gender, Class, and Ethnicity in Nineteenth-Century New York City ABSTRACT Ceramic vessels are used in a first step for comparing how working- and middle-class women constructed domesticity in 19th-century New York City. In addition to exploring some of the interpretive problems encountered in studying workingclass families who lived in tenements, the analysis indicates that the women of the working class apparently did not emulate middle-class women when it came to choosing the dishes they used to set their tables. Introduction One of the issues that historical archaeologists have become increasingly interested in exploring is how to use material culture to study the construction of class. Many archaeologists would agree with Bourdieu (1984:48) that “[a] class is defined as much by its being perceived as by its being, as by its consumption-which need not be conspicuous in order to be symbolic-as much as by its position in the relations of production (even if it is true that the latter governs the former)” (emphasis in the original). Therefore they expect to be able to see differences among classes expressed in the material culture which the members of these classes left behind. As archaeological data on many different socio-economic groups accumulate throughout the country, archaeologists are now in a position where they can begin to explore the construction of class. Those studying New York City are particularly fortunate in this regard. Due to the vagaries of modern development and environmental regulations, archaeologists working in New York over most of the past two decades accumulated a number of assemblages that originated in middle-class and elite households (Geismar 1983, 1989; Rockman et al. 1983; Grossman 1985; Berger and Associates 1987, 1991; Rothschild, Historical Archaeology, 1999, 33(1):102-117. Permission to reprint required. Wall, and Boesch 1987; Rothschild and Pickman 1990;; Salwen and Yamin 1990). More recently, they have begun to acquire assemblages from poorer neighborhoods, such as the Five Points (Yamin 1997) and Kleindeutschland (Grossman 1995), as well. The addition of the information from these working-class assemblages to New York‘s research data base will soon allow archaeologists to make extensive comparisons between working- and middle-class households during the process of class formation in the 19th century. As an anthropologist enamored of the comparative approach (or historic ethnology[Schuyler 1988]), the author is particularly interested in using the material culture of domesticity to compare the construction of gender and women’s roles-and particularly the meanings of domestic life-between the women of the working class and those of the middle class. More specifically, the interest is in exploring the extents to which class and ethnicity, respectively, structured the construction of gender in the 19th-century metropolis. This preliminary study attempts to show some of the approaches that archaeologists might use to study class, ethnicity, and gender in an urban setting. It begins by introducing the outlines of what is known about the lives of women of the middle and working classes in New York at the middle of the 19th century. Then, it explores an admittedly very small sample of assemblages by examining, first, the 19th-century neighborhoods where the assemblages were found. Next, the study examines the contexts of the families who lived on the sites where the assemblages were found and who presumably used the artifacts that make up the assemblages. Finally, using one medium of the material culture recovered from the archaeological excavations-the china dishes used in presenting meals-it examines some of the interpretive problems that archaeologists are beginning to encounter in studying the lives of working-class people in the 19th-century tenements, and points out some possible differences in the meanings of domestic life for the women in these households. In examining two of the EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNlClTY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY three middle-class homes, the author uses data analyzed for other, earlier studies (Wall 1991, 1994); the data from the middle-class 12th Street site and from the tenement are presented here for the first time. Class and Gender in 19th-Century New York The 19th century saw the beginnings of the formation of the American class system that exists today (Blumin 1989; Wilentz 1984). After the mid-19th century, the middle class in New York was made up for the most part of Protestants who had been born in the United States (Stott 1990:242). At that time, The New York Times described this group as including “professional men, clergymen, artists, college professors, shopkeepers, and upper mechanics” (Blumin 1989:247). The latter, who had been master craftsmen under the old artisan system of production, had become managers who supervised the work of their employees but who did not work with their hands. In fact, one historian has used this dichotomy between manual and non-manual labor as crucial in distinguishing the working class from the middle class in urban America after the Civil War (Blumin 1989). Middle-class wives and daughters did not work outside the home; instead, as can be learned from both historical accounts and the contemporary prescriptive literature, their roles were predicated on the two interrelated ideals of “true womanhood” and refined gentility. Middle-class women perceived themselves and were perceived by others of their class as the moral guardians of society, a role they exercised both within their homes (among both family members and the live-in domestics whose work they supervised) and in society at large (particularly among the working classes). They were also, however, responsible for projecting the image of their families’ gentility, an important issue for negotiating the family’s position in the city’s class structure. The latter role was particularly critical in social reproduction: in order to provide access to the middle class for their children, parents needed 103 friends to help provide suitable places in business for their sons and fitting husbands for their daughters (Stansell 1986; Blumin 1989). During the 19th century, the middle-class ideology of morality, respectability, and gentility coalesced into the dominant world view in American culture, a position that middle-class ideology continues to hold to this day. The first half of the 19th century also saw the formation of the working class. As the artisan system of production broke down, most of the journeymen who had been able to look forward to becoming master craftsmen in their own right in the 18th century had become, along with the semi-skilled, part of a permanent wage-earning working class by the middle of the 19th century. Their children, who would earlier have been apprentices, now made up a pool of child labor. These wage earners and piece workers lived in working-class neighborhoods and either worked in their employers’ shops or at home as part of the outwork system. New York City’s working class had invented itself twice by the middle of the 19th century (Gutman and Berlin 1987). The first working class had formed before the 1840s. It consisted of a heterogeneous group of predominately native-born people who worked with their hands and who had inherited the republican artisan ideology of the Revolutionary War (Wilentz 1984). This class did not reproduce itself to become the working class of mid-century, however. Instead, its identity was swamped by the waves of immigrants who began arriving in New York in the 1840s. Between 1840 and 1855, the city’s population doubled and immigration played an important role in its growth: in 1855 over half of its population of almost 630,000 was foreign-born (Rosenwaike 1972:16, 42). Most of these immigrants were manual workers. It has been estimated that in 1855 approximately 84% of the city’s manual work force had been born overseas (Stott 1990:72). It was these immigrants and their children who transformed the city’s working class by drawing on ideological and cultural roots developed in Europe. Immigrants have continued 104 to dominate the workforce and hence to shape the city’s working class off and on throughout much of its history, from the 19th century until today. At the middle of the 19th century, the Irish and the Germans were the most numerous of the immigrants who had settled in New York. Furthermore, there were almost twice as many Irish men and women in the city as their German counterparts (Rosenwaike 1972:42). Many Irish men worked as laborers, bricklayers, and stonecutters, while German men tended to work at cabinetmaking, cigarmaking, shoemaking, tailoring, and baking (Stott 1990:92). Various studies have shown that a workingman’s wage was usually not enough to support a family in the 19th century (Wilentz 1984; Stansell 1986). Therefore at least in part for this reason, the women of the working class, unlike middle-class women, helped make ends meet by using various economic strategies that they performed both inside and outside their homes. Like the work of working-class men, the work of working-class women was structured in part by their ethnicity. Many young unmarried Irish women (most of whom had immigrated on their own) worked as servants, living in the homes of the middle- and upper-class women who were their employers. In fact, census records indicate that more women in New York worked in domestic service than in any other sphere: in 1855, there were over 31,000 women employed as servants in the city (Stansell 1986:72). Many women, both married and single, produced goods or performed services for market in their homes. Some, particularly Irish women, worked as seamstresses or laundresses, while others, particularly German women, worked alongside their husbands and children in familyorganized shops in the tailoring and other trades. The working roles of many of these workingclass women are hidden in the census records. Most women who worked in their homes as part of the family economy were listed with no occupation in the census returns and are therefore usually interpreted as having been housewives, HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33( 1) who by definition do not contribute economically to their household by producing goods or services for market. Furthermore, the women of many ethnic groups who were listed without occupations in the records provided accommodations for boarders, who were often recent arrivals from the householder’s native land (Stansell 1986; Griggs 1996:9). Although scholars are learning more about the experience of the women of the working class in the 19th-century city, they know relatively little about their visions of domestic life. In contrast, contemporary sources provide ample data on the 19th-century middle-class (and on middle-class women in particular). Scholars have described the culture of the middle-class as a whole as “feminine,” a culture of domesticity, and it is therefore closely identified with middle-class women (Douglas 1977; Stott 1990:270). This is the culture described in the novels that middleclass women read and the literature that prescribed how they should live. The culture of working-class women, on the other hand, differs greatly from that of middleclass women in this regard. Several scholars have noted that urban working-class culture was perceived in the 19th century as a “masculine” culture (Stansell 1986:lOO; Stott 1990:270). This suggests that although contemporary sources might be used to reconstruct the culture of working-class men, the lives of their mothers, sisters, wives, and daughters remain invisible. As historian Christine Stansell (1986:xiii) points out, “it is easy to imagine these women . . . as either feminine versions of working-class men or working-class versions of middle-class women.” In order to delineate the lives of working-class women in their own right, scholars cannot turn to the novels they read or to the advice books that prescribed how they should live, because neither literature exists. Even if this literature did exist, working-class women, assuming they knew English and could read at all, would have rarely had the leisure time to read. So instead of being able to consult contemporary literature, schol- EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNICITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURYNEW YORK CITY ars have to turn to material culture to answer many questions about the lives of working-class women. Such questions might include: Did working-class women, following the dominant ideology thesis (Hodder 1986; Leone 1988; Beaudry et al. 1991) emulate the middle class and aspire to gain entry to the bourgeoisie so that either they or their children could partake of its power? (It must be remembered in this context that many working-class women certainly knew a great deal about middle-class domestic life from their years in domestic service, when they lived in middle-class homes, before they were married.) Or did working-class women (along with their men) take pride in their own, distinctive workingclass subculture? One historian notes that at least some workers who were not poor did not aspire to the bourgeoisie; he quotes a British visitor to the city who says that “[t]he miserable ambition to be accounted ‘genteel’ . . . [is] not among the national characteristics” (Stott 1990:189). Or did the women of the immigrant communities that made up the second working class choose to by-pass class identity and instead to mobilize ethnic identity and construct a form of domestic life that was specific to their ethnic group? Or, finally, did some working-class women follow one strategy and others, others? These are some of the questions about the construction of domestic life that archaeological data might help to address by allowing the comparison of, for example, the different styles of ceramic vessels used for presenting meals among the working class as opposed to among the middle class. Four Middle-class and Working-class Families in Mid-19th Century New York The domestic assemblages considered here were found in backyard features (privies and cis- 105 terns) on four separate archaeological sites: 50 Washington Square South (the upper deposit of Feature 9; Salwen and Yamin 1990; Wall 1991, 1994), 25 Barrow Street (Wall 1991; Bodie 1992), 153 West 12th Street (Brighton in press), and 365 East 8th Street (Grossman 1995). All four sites are located in a part of New York City that is broadly known as “the Village” today, but that was made up of many different neighborhoods in the 19th century. During the colonial period, this area consisted of hamlets, farms, and country estates that were then located about a mile north of the city; the commercial hub of the area was the village of Greenwich, which was located on the Hudson River. The village and its environs were linked to the city by river boats and by “the road to Greenwich,” today’s Greenwich Street, as well as by Broadway and the Bowery, located further to the east. In the early 19th century, however, the city approached the village in its growth northward, and real estate speculators began to look on the area as ripe for development. 50 Washington Square South During the 1820s, some village developers were successful in petitioning the city to have the old Potters’ Field to the west of Broadway converted into the parade ground that later became known as Washington Square Park. This park soon became the focus of the rows of brick Federal and Greek Revival houses that were home to many of the wealthier members of the middle class in what was becoming one of the city’s first residential suburbs. The men from these families commuted to their downtown offices in horse-drawn omnibuses; these conveyances were introduced in the 1830s to meet their commuting needs. In his novel Washington Square, Henry James (1982 [1880]) described this neighborhood as embodying in 1835 “the ideal of quiet and genteel retirement,” with an air “of established repose which is not of frequent occurrence in other quarters of the long, shrill city.” 106 The Federal house at 50 Washington Square South was built in 1826 as part of this development. The southern side of the square was somewhat less expensive than its northern counterpart because of its proximity to the poorer neighborhoods (including an African-American community) that were developing immediately to its south. In 1841, Eliza Robson moved into the house with her husband Benjamin, a physician, and her brother, James Bool. Before they had moved to Washington Square, the Robsons had lived downtown on East Broadway, where the couple had raised their three children and where Benjamin had conducted his practice out of the family home. After they moved, the doctor continued to run his practice from his old downtown office. The Robsons presumably chose the house on Washington Square South because it was close to their grown daughter, Mary Sage and their grandchildren, who lived next door. Mary’s husband Francis Sage was a flour merchant who commuted to his countinghouse on downtown Front Street. The Robsons continued to live on the property until Benjamin’s death almost four decades later. The Robsons were clearly among the wealthier families of the middle class. They lived in the relatively exclusive enclave of Washington Square in a three-and-a-half story single-family home they owned themselves. They had live-in domestic help (consisting of two Irish women) and even kept a carriage driven by an AfricanAmerican coachman for part of the period that they lived there; the doctor presumably used the carriage to commute back and forth from his office downtown (Wall 1991, 1994). HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33(1) opers (many of whom were builders by trade) began to line the streets with small, single-family Federal and Greek Revival houses. These buildings were designed as homes for the poorer members of the city’s middle-class: the city’s artisans and shopkeepers who for the most part worked nearby. By the middle of the 19th century, many of these small but respectable middleclass houses had been converted into multi-family homes to help supply the city’s ever-growing housing needs. Like many of its neighbors, the house at 25 Barrow Street was originally built as a two-anda-half-story, single-family Federal house in 1826 but by mid-century it had become home to two separate families. In 1858, Emeline Hirst and her husband Samuel, a baker, and their six children moved into the house. Although Samuel died two years later, his family stayed on in the house for over a decade. They supported themselves through the earnings of Emeline (who worked first as a nurse and then ran a boardinghouse) and the older children. Other tenants who lived in the house during the Hirsts’ tenure included David Sinclair, a Scottish locksmith, his wife, Selina (who was born in New York), and their two children, who lived there for only a few years, from 1858 until 1862. Sinclair had his shop on nearby Bleecker Street. The Sinclairs were probably succeeded in the house by other families or boarders taken in by the widowed Emeline Hirst, but their identity has not been documented. These families too were members of the city’s middle class: the male heads of the households had small businesses, while one of their sons described himself as a “clerk,” the quintessential middle-class occupation of the late 19th century. 25 Barrow Street Data suggest, however, that these families beAt the same time that some developers were longed near the bottom of the middle class spectransforming the old Potters’ Field into the elite trum: First of all, they rented, rather than suburb of Washington Square, others were focus- owned, their homes, and their homes were aparting on the crooked streets to the west of Sixth ments, and not single-family houses. Secondly, Avenue and to the south of Greenwich Avenue none of the families enjoyed the services of livein today’s West Village. Here, small-scale devel- in domestic help, a luxury which was fairly com- EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNlClTY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY mon among middle-class New Yorkers at midcentury. Finally, when Emeline Hirst was widowed, she and her family seem to have made a change in economic strategy from the family consumer economy (commonly used by the middle-class) to the family wage economy, whereby the wages of family members are pooled for the good of the family as a whole, a strategy that the working poor commonly used (Tilly and Scott 1978; Wall 1991, 1994). 153 West 12th Street In the 1840s, almost two decades after the development of the Washington Square area, developers began to build up the northern part of today’s West Village with Greek Revival brick and brownstone single-family homes designed for the solid middle-class. Most of these houses continued to be single-family homes until well after the Civil War. The three-story Greek Revival house at 153 West 12th Street was built as a single-family home ca. 1841. In 1855, 29year-old Henrietta Raymer and her 37-year-old husband Henry moved into the house as tenants; they continued to live there for a decade. Henry Raymer was an importer of groceries and commuted downtown to his business on Front Street in the lower city. In 1860, the household included the New York-born Raymers, their two young children, George and Maria (who were then aged two and four, respectively, and who were born while the family lived in the house), as well as two domestics, Catherine Henn and Anne Hines, who had emigrated from Germany and Ireland, respectively (Bureau of the Censusl860). By 1865, Henry Raymer had died; his widow and young children moved out of the house soon thereafter. The 12th Street Raymers were definitely members of the middle class. They lived in a singlefamily home and enjoyed the services of live-in domestic help. The young family did not own their own home, however, suggesting they were not at the upper end of the middle-class spectrum. 107 365 East Eighth Street In the early 19th century, developers built up the area to the east of Tompkins Square Park in today’s “East Village” with single-family homes to house the predominately native-born workers who worked in the shipyards that were located nearby, in and adjacent to the East River. The city’s shipbuilding industry soon became one of the largest in the world. After the Civil War, however, the high costs of both labor and real estate forced most of the yards to move away from New York. Even before the decline of the shipbuilding industry, the residential component of the neighborhood had begun to change. During the 1840s, large numbers of Germans began to move into New York, which by 1855 had become the city with the third largest German population in the world (Nadel 1990:viv). In this same year, over half of the population of the 11th Ward, where the shipyards were located, had been born in Germany and the neighborhood was known as Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany. This ward was also the site of other industries, such as slaughterhouses, breweries, and coal- and lumberyards, that, like the shipyards, required large tracts of land (Nadel 1990:29, 32). Samuel Gompers, the founding president of the American Federation of Labor, lived in this neighborhood and worked alongside his father as a cigarmaker when he was a young teenager in the mid-1860s. His memoirs (Nadel 1990:35) provide a vivid impression of what it was like to live in Kleindeutschland then: Father began making cigars at home and I helped him. The house was just opposite a slaughterhouse. All day long we could see the animals being driven into the slaughter pens and could hear the turmoil and the cries of the animals. The neighborhood was filled with the penetrating, sickening odor. The suffering of the animals and the nauseating odor made it physically impossible for me to eat meat for many months after we had moved into another neighborhood. Back of our house was a brewery which was in continuous operation, and this necessitated the practice of living-in for the workers. Conditions were dreadful in the breweries of those 108 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33(1) TABLE 1 THE BUILDINGS LOCATED ON THE SITES IN 1860 No. Housing Units Value of Bldg. No. Floors in Bldg. No. Floors/ Housing Mean Value/ Unit Housing Unit 8th Street Barrow Street 12th Street Washington Sq. 4 2 112 3 3 112 $4200 2600 5000 10200 8 2 1 1 1 3 3 $525 1300 5000 10200 NOTE: Based on data from the New York City tax records (City of New York 1860). days and I became familiar with them from our back door. tailoring trades and several of their sons worked as cigarmakers. The tailors may have worked at The four-story tenement at 365 East 8th Street home in family shops alongside their wives and was built ca. 1852 in the neighborhood that was children because in the 1850s, piece rates were quickly becoming Kleindeutschland. In 1864, so low that many tailors could not expect to Joseph Sonnek, a German-born tailor, bought the make a living on their own but had to pool their tenement from Meyer and Mina Goldsmith and a labor with that of their family members. This few years later he and his family moved into the way of life was well-expressed by the German building. In 1870, a total of eight families (in- maxim, “A tailor is nothing without a wife, and cluding the Sonneks and their three children) very often a child” (Stansell 1986:117). Some of lived in the building. Almost all of the adults in the tailor-tenants may have worked for their landthese families were foreign-born, immigrants lord, who by 1880 had built a tailor shop behind whose countries of origin were divided almost the tenement (Trow 1880). Their Irish neighbors equally between Ireland and Germany. Both and the latter’s sons worked as riggers and boiler Sonnek and his wife Julia had been born in makers in the shipyards that remained nearby, while Irish daughters worked as dressmakers and Dressen (Grossman 1995). Most of the residents of the 8th Street tene- “operators” in factories (Grossman 1995). Tables 1 and 2 summarize the information on ment worked at skilled occupations: in 1870, all of the German heads of household worked in the the four houses and the people who lived in TABLE 2 THE TERMINUS POST QUEM DATES FOR THE DEPOSITS AND THE PEOPLE LIVING IN THE BUILDINGS AROUND THE TIME THE DEPOSITS WERE FORMED 8th Street Barrow Street 12th Street Washington Sq. T.P.Q. Year No. Families No. Indiv. No. Domestics/ Housing Unit 1867 1863 1864 1857 1870 1860 1860 1860 8 2 1 1 42 12 6 4 0 0 2 2 NOTE: The sources for the terminuspost quem dates are: Grossman (1995) for 8th Street, Bodie (1992) for Barrow Street, Nancy J. Brighton (1997 pers. comm.) for 12th Street, and Salwen and Yamin (1990) for Washington Square. The data on the people are based on information from the census records for the closest census year United States Bureau of the Census 1860,1870). EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNlClTY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY 109 TABLE 3 IRONSTONE AND WHITEWARE TABLE VESSELS BY DECORATIVE TYPE WORKING CLASS MIDDLE CLASS 8th Street Barrow Street n PLAIN EDGED PRINTED-WILLOWPRINTED-OTHER % 1 8 1 8 MOLDED WHITE-ON-WHITE GOTHIC 2 OTHER 8 % n 5 1 1 17 61 12th Street 6 38 8 8 46 OTHER TOTALS 12 100 13 them. They show that these middle-class and working-class families encountered a great range of experience in terms of their living conditions. The three people who made up the wealthy middle-class Robson family of Washington Square lived in a three-and-a-half story singlefamily home and enjoyed the services of several domestic servants. Their home was assessed at over $10,000. The forty people who occupied 100 n Washington Square n % % 4 1 29 7 4 5 12 15 3 21 5 15 5 36 19 58 1 7 14 100 33 100 the four-story Eighth Street tenement lived in eight apartments with an average of five tenants each. Each tenement family had to settle for a half a floor of living space, which was assessed at only $525, a mere 1/19th of the value of the Robson family’s living space. They enjoyed no domestic help other than that of family members. Many had to haul water for household use up several flights of stairs and then to haul slops TABLE 4 PORCELAIN PLATES FROM THE FOUR ASSEMBLAGES WORKING CLASS MIDDLE CLASS 8th Street Barrow Street plain molded-paneled gilt painted TOTAL 12th Street Washington Square 18 4 4 I 0 1 3 22 NOTE: All of the porcelain plates in the assemblages are small, either muffins or twifflers. 7 110 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33(1) FIGURE 2. Ironstone teacup in the paneled Gothic pattern. (Courtesy of the South Street Seaport Museum.) FIGURE 1. Ironstone plate in the Gothic pattern. (Courtesy of the South Street Seaport Museum ) same phenomenon in a middle-class community in Brooklyn, which was an independent city until the 1890s when it became part of the City of New York. Table 4 shows that all of the middle-class families also had porcelain plates; these plates, which were all relatively small (they would be described as twifflers or muffins in the ceramics literature), are discussed below. down again. These bare statistics, however, do not allow modern-day scholars to grasp the nuances of the experience of those who lived in these homes. To begin to do that, they must turn to material culture. The Ceramics Used by Middle-class Women Table 3 shows the different kinds of ironstone and whiteware plates that the middle-class women used to set their tables. The most prominent feature of the assemblages is the popularity of the 12-sided Gothic ironstone plates in all three households (Figure 1). This consistent preference for ironstone plates in the Gothic style in both wealthier and poorer middle-class homes is the most striking phenomenon that archaeologists find in examining assemblages from middleclass mid- 19th-century New York. This style was preferred by the residents Of Some Other American cities as Fitts (Fitts and Yamin 1996; Fitts this volume) discovered the FIGURE 3. European porcelain teacup with gilt decoration in the ltalianate style. (Courtesy of the South Street Seaport Museum.) EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNlClTY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY As Table 5 shows, in buying teawares, all the middle-class women chose at least some cups and saucers with molded panels in the Gothic pattern (Figure 2), presumably to go with their Gothic plates, for drinking coffee or tea with their meals. In addition to their Gothic-style cups and saucers, the wealthier middle-class women-Eliza Robson and Harriet Raymer-also chose dishes in other, fancier Italianate styles (included in the categories of painted and applied porcelains in Table 5; Figure 3). The poorer middle-class women of Barrow Street, however, did not opt for the fancier teawares; instead, they apparently usually used their plain or Gothic- 111 styled teacups and saucers whenever they served tea. The Ceramics Used by Working-class Women The ironstone and whiteware plates from the tenement (Table 3) are superficially quite similar to those from the middle-class homes-the preferred patterns are all generally in molded whiteon-white ironstone designs. When examined more closely, however, it becomes apparent that the styles are really quite different. Instead of showing a consistent preference for dinner plates in the 12-sided Gothic pattern as all three TABLE 5 TEAWARE VESSELS BY DECORATIVE TYPE PLAIN cc ironstone porcelain PAINTED calico WORKING CLASS MIDDLE CLASS 8th Street Barrow Street 12th Street Washington Square % n % 6 3 38 0 n % n % (3) 0 0 0 14 0 0 0 5 MOLDED PANELS cc ironstone porcelain 50 3 38 45 MOLDED OTHER ironstone 39 2 (2) 25 0 PAINTED PORC. 6 0 0 7 9 16 36 APPLIED PORC. 0 0 0 14 19 0 0 101 8 101 74 99 44 100 PRINTED cc TOTALS (3) 112 HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33(1) Discussion among the assemblages. The Washington Square middle-class assemblage dates to the 1850s, almost a decade before the other three assemblages (two of which are middle class and one of which is working class; Table 2 lists the terminus post quem dates for each of the assemblages). The ceramics in the two later middle-class assemblages (Barrow Street and 12th Street) are much more similar to the Washington Square assemblage than they are to the working-class Eighth Street assemblage, which they are much closer to in time. For example, the remarkable preference for Gothic ironstone plates expressed in all of the middle-class assemblages (even though they date to two different decades) was not evident in the working-class assemblage, which was roughly contemporary with two of the middle-class assemblages. Therefore, the variability among the Before attempting to explain the differences between the assemblages in cultural terms, a brief discussion of the dates of the assemblages is warranted to see if the variability among the assemblages might be most economically explained by time. Ceramic specialists and writers of the prescriptive literature agree that the British potteries first introduced sets of all-white ironstone dishes to the American market in the early 1840s (Wetherbee 1996:vi) and that by 1850, “china ware of entire white [seemed] . . . to have superseded all others . . .” (Leslie 1850:290). Although these dishes continued to be popular until the end of the century, there was evidently a sea change in the kinds of patterns of ironstone dishes that were preferred in the United States during this long period: prior to around 1870 (and during the period discussed here), the vessels that made up these sets tended to be sharply angled or molded with great detail, while the styles became much simpler, “emphasizing plainer rounded and square shapes,” in the 1870s (Wetherbee 1996:10). Although the assemblages from the four backyard features analyzed here date to different decades of the 19th century, time does not seem to be the variable that can explain the differences FIGURE 4 Ironstone plate in the Bowknot pattern. (Courtesy of the South Street Seaport Museum.) middle-class families did, most of the plates are round in cross-section and show a whole array of molded patterns, including the Bowknot, Huron, Dallas, and Sydenham designs (Wetherbee 1996; Figure 4). These designs are completely absent from the middle-class assemblages. In choosing teacups (Table 5), the Eighth Street women, like their counterparts among the lower middle-class on Barrow Street, preferred paneled cups in the Gothic pattern, although they used ironstone cups in other patterns (including the Full Ribbed, Dallas, and Ceres designs [Wetherbee 19961) as well. The Eighth Street women eschewed for the most part the fancier porcelain cups and plates used by the wealthier middle-class women (Tables 4, 5). EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNlClTY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY assemblages is better explained by differences in class, rather than by differences in time. Archaeologists have devoted a great deal of thought to deciphering “the language of dishes” and trying to understand the meanings of the different kinds of ceramic sherds that are so ubiquitous at their sites (Wall 1991, 1994; Shackel 1996). Elsewhere this author (Wall 1991, 1994) has argued that the middle-class preference for setting the table for family meals with dishes in the Gothic style (which also became the popular architectural style for building churches in the 1840s) was related to the importance of one of the roles of middle-class women at mid-century: that of the guardian of society’s morals. The use of this ecclesiastical style for dishes used in a dining room that the authors of the prescriptive literature urged be furnished in that same style underlined the importance of morality and of women’s role as moral guardian of the family members who gathered for the meal. The Gothic style for tablewares contrasted with the Italianate style that characterized the porcelain teacups and saucers that were used alongside small porcelain plates for entertaining at evening parties among the wealthier members of the middle class. The city’s architects also used the Italianate style for building the middle-class rowhouses that by mid-centuy were making definite statements about class (Lockwood 1972). Advice writers urged women to furnish their parlors, where they held the evening parties that were their vehicles for entertaining, in this same Italianate style (Downing 1850:23-24). Middleclass women used these entertainments (and the Italianate style in which the parties’ accoutrements were executed) to exercise their other important role, that of projecting the image of their families’ gentility and negotiating the families’ position in the class structure. As noted above, however, not all middle-class women apparently exercised this role, as no fancy porcelain cups were found in the Barrow Street assemblage. Perhaps the poorer middle-class women of Bar- 113 row Street perceived that dazzling their friends with sumptuous ceramics was not necessarily a productive strategy in an environment where they might need the help of their peers to maintain their precarious position at the lower end of the middle class (Wall 1991). The working-class assemblage allows some inferences to be made about the working-class women of Eighth Street. The diversity in the patterns of the ironstone plates indicates that at least some of the women who lived in the tenement were not emulating their middle-class contemporaries by choosing plates that were uniformly in the Gothic pattern. This suggests that they therefore also were not emulating middleclass women in the latter’s role as the moral guardian of the home. At least some of the women of Eighth Street, however, did choose teawares in the paneled Gothic pattern. Perhaps this style had a completely different meaning for working-class women than it had for their middle-class contemporaries. Or perhaps these poorer women, like the women of the middle-class, chose to mobilize a “sacred” meaning for this style so that they could elicit the “sacred” ties of morality and community when a friend stopped by for tea, ties that served to soften the blows of poverty. The ubiquity of the Gothic pattern among the middle-class assemblages also underscores another characteristic of family meals in middle-class homes in the 19th century which still typifies middle-class meals today: the use of matched dishes. If differences in style express social boundaries (Wobst 1977), then the unity of style expressed by the use of a set of matched dishes should emphasize the community of a group rather than the differences among its individual members. The matched set of dishes allows the communal aspect of the meal to be stressed even in the face of the use of individualized plates and place settings. Although using matched sets of dishes in family meals is what middle-class Americans do today and what they seem to expect, correctly, of 114 their 19th-century counterparts, tables can theoretically be set in other appropriate ways as well and in fact they apparently were in the United States in the 19th-century. For example, archaeologists have long noted the fact that they do not find matching sets of dishes in some AfricanAmerican and African-Caribbean assemblages (Armstrong 1990:135-136, Mullins 1995); instead, they find arrays of dishes in patterns that do not match each other. Some archaeologists have explained this phenomenon by making the perhaps ethnocentric interpretation that these households aspired to emulate the dominant culture in using matched sets of dishes but failed in that attempt (Mullins 1995; Orser and Fagan 1995:213, 215). It seems apparent, however, that at least some groups of people of African descent who lived in the Americas had a different ideology of domestic life than many of their middle-class counterparts of European descent and that they expressed that ideology when they set the table. Instead of using sets of matching plates to mark the corporate unity of the household as a unit, each individual family member had his or her own individual dishes that he or she used at daily meals. If the goal is for each household member to use his or her own individual dishes, the plates used by the household cannot match, or family members would not be able to tell which plates belonged to whom. This custom of using personal dishes (along with the use of personal silverware and chairs) seems to have been prevalent among many African-American and African-Caribbean families in the 19th and 20th centuries and perhaps earlier as well (BaldwinJones 1995). Baldwin-Jones offers a possible explanation for this phenomenon: “In the face of slavery where people of various cultures were brought together as property and [were] treated as less than human, [one was forced] to create an identity for oneself. . . [a] sense of individuality that would lead to using unmatched dishes, and other personal items to create such an autonomy” (Baldwin-Jones 1995:3-4). Perhaps the importance of individual improvisation in jazz, HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33(1) the quintessential African-American art form, is also an expression of this phenomenon. One must remember the different languages that plates can speak in trying to interpret the meaning of the ceramics from the working-class tenement on Eighth Street. There, the diversity in the white-on-white patterns on the ironstone dishes shows that there is something very different going on in regard to the ideology of domestic life in the working-class tenement than was seen in the middle-class homes, where ironstone plates were almost exclusively in the Gothic pattern. Unfortunately given the multi-family nature of tenement life and the economic and ethnic heterogeneity of the people who lived in the tenement building, there is much that is not known about the cultural context of the assemblage. For example, it is not known if the assemblage originated in one household or in several households. It also is not known whether it was used in one or more Irish households, one or more German households, or households of both ethnic groups. Furthermore, it is not known if the assemblage were used in the home of the Sonneks, who owned the tenement as well as the later tailor shop in the rear of the yard and who therefore were not true members of the working class; or in the homes of one or more of their tenants, who were probably wage laborers or piece workers with little or no capital; or if part of the assemblage were used in the Sonneks’ home and part in the home(s) of their tenants. If there were no problems of cultural context, the analysis of the assemblage would be much more clear-cut. If the variables of the wealth and ethnicity of the household(s) that the dishes came from could be controlled, and if it were known that each plate pattern came from the household of a different ethnic group, it could be inferred that the women of the Eighth Street tenement used plate patterns to help mark the ethnic identity of their families: the women from the Irish families preferred china in one molded style while those from the German families preferred china in another pattern. Or if it were known that the assemblage came from several EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNlClTY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY households that belonged to only one ethnic group, it could be supposed that each housewife exercised her individual preference for a particular style of dishes within the white-on-white molded style, and that the particular pattern that she chose had no meaning in terms of class or ethnic identity. Or if it were known that all of the unmatched dishes came from a single household, it could be inferred that that housewife may have spoken the same language of plates as that of the Americans of African descent described above: perhaps since each individual family member had his or her own individual dishes that he or she used at meals, each person had to have his or her own personal plate in a unique pattern, so that the dishes belonging to one person could be differentiated from those belonging to another. Unfortunately with the problems of provenience there is not enough information available at this point for archaeologists to be able to tell what the diversity of style among the tenement plates means. Presumably, as more assemblages from working-class homes are added to our data base, patterns of consumption on the part of the working-class women of various socio-economic levels and various ethnic groups will become clear. It is hoped that archaeologists will learn to read and understand the patterns of consumption that people in the 19th-century city were using to define their position in the class structure. 115 East Eighth Street site. I also thank Diane Dallal of the South Street Seaport Museum for her undeviating hospitality in making the Sullivan Street and Eighth Street collections accessible to scholars. Finally, I thank Robert Fitts, Randall McGuire, and Nan Rothschild for reading and commenting on earlier drafts of this paper. Unfortunately, however, all errors of fact or interpretation are my own. REFERENCES ARMSTRONG, DOUGLAS 1990 The Old Village and the Great House. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. BALDWIN-JONES, ALICE 1995 Historical Archaeology and the African American Experience. Paper submitted for Historical Archaeology, Program in Anthropology, CUNY Graduate Center, New York. BEAUDRY, MARY,LAUREN J. COOK, AND STEPHEN A. MROZOWSKI 1991 Artifacts and Active Voices: Material Culture as Social Discourse. In The Archaeology of Inequality, edited by Randall H. McGurie and Robert Paynter, pp. 150-191. Basil Blackwell, Oxford, England. BERGER, LOUIS,AND ASSOCIATES 1987 Druggists, Craftsmen, and Merchants of Pearl and Water Streets, New York The Barclays Bank Site. Submitted to London and Leeds Corporation from Louis Berger and Associates. 1991 Archaeological and Historical Investigations at the AssaySite,Block35, NewYork,NewYork. Submitted to HRO InternationalfromLouisBergerandAssociates. BLUMIN, STUART M. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS As we all know, the practice of archaeology is a group effort. Here, I want to acknowledge the generous help of those who made this study possible. For facilitating access to archaeological sites, data, and collections, I thank the following people: Jean Howson, the late Bert Salwen, and Rebecca Yamin for access to data from the Sullivan Street site; site owners Arlene and Harry Nance, and archaeologists Debra Bodie and the late Bert Salwen for help with the Barrow Street site; site owner Cooper Union and site occupants Jay and Leah Iselin, and archaeologist Nancy Brighton and researcher Daphne Joachim for help with the 153 West 12th Street site; and Richard Clark for his assistance with the 365 1989 The Emergenceofthe Middle Class: SocialExpevience in the American City. Cambridge University Press, London, England. BODIE,DEBRA C. 1992 The ConstructionofCommunityinNineteenthCentury New York ACase StudyBasedontheArchaeological Investigationofthe 25 Barrow Street Site. Manuscript, New York City LandmarksPreservationCommission, New York. BRIGHTON, NANCY J. 1999 Untitled M.A. thesis on the 153 West 12th Street Site. Department of Anthropology, New York University, New York. 116 BOURDIEU, PIERRE 1984 A Social Critique of the judgement of Taste, translated by RichardNice. HarvardUniversity Press, Cambridge, MA. CITYOF NEWYORK 1860 Tax Assessment Records. Municipal Archives, Department ofRecords andInformationServices,New York. DOUGLAS, ANN 1977 The Feminization ofAmerican Culture. Knopf, New York. DOWNING, ANDREW JACKSON 1850 The Architecture of Country Houses. D. Appleton, New York. FITTS,ROBERT K. AND REBECCA YAMIN 1996 The ArchaeologyofDomesticityinVictorianBrooklyn: ExploratoryTesting and Data Recovery at Block 2006 of the Atlantic Terminal Urban Renewal Area, Brooklyn, New York. Submitted to the Atlantic Housing Corporation and Atlantic Center Housing Associates from John Milner Associates, Inc. GEISMAR, JOANH. 1983 The Archaeological Investigation of the 175 Water Street Block, New York City. Soil Systems, Inc. New York City LandmarksPreservationCommission, New York. 1989 History and ArchaeologyoftheGreenwichMews Site, Greenwich Village, New York. Submitted to Greenwich Mews Associates. New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York. GRIGGS, HEATHER J. 1996 “By Virtue of Reason and Nature”: Competition and Economic Strategy in the Needletrades in MidNineteenth Century New York City. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Council for Northeastern Historical Archaeology, Albany, NY. GROSSMAN, JOEL 1985 The Excavation of Augustine Heerman’s Warehouse and Associated 17th Century Dutch West India Company Deposits. Greenhouse Consultants, Inc. New York City Landmarks PreservationCommission, New York. 1995 The Archaeology of Civil War Era Water Control Systems on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, New York. New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York. HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY 33( 1) GUTMAN, HERBERT G. WITH IRABERLIN 1987 Class Composition and the Development of the American Working Class, 1840-1890. In Power and Culture: Essays on the American Working Class, edited by Herbert G. Gutman,pp. 380-394. Pantheon, New York. HODDER, IAN 1986 Reading the Past: CurrentApproaches toInterpretation inArchaeology. Cambridge UniversityPress, London, England. JAMES, HENRY 1982 Washington Square, reprint of 1880 edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England. LEONE, MARKP. 1988 The Georgian Order as the Order of Merchant Capitalism in Annapolis, Maryland. In The Recovery of Meaning: Historical Archaeology in the Eastern United States, edited by Mark P. Leone and Parker B. Potter, pp. 235-261. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington. LESLIE, ELIZA 1850 Miss Leslie’s Lady’s House-Book; A Manual of Domestic Economy. A. Hart, Philadelphia, PA. LOCKWOOD, CHARLES 1972 Bricks and Brownstone: The New York Row House, 1783-1929, an Architectural and Social History. McGraw-Hill, New York. MULLINS, PAULR. 1995 “A Bold and Gorgeous Front”: The Contradictionsof African American and ConsumerCulture, 1880-1930. Revision of The Historical ArchaeologyofCapitalism, a paper presented at School of American Research Seminar. NADEL, STANLEY 1990 Little Germany: Ethnicity, Religion, and Class in New York City, 1845-1880. University of Illinois Press, Urbana. ORSER,CHARLES AND BRIAN FAGAN 1995 Historical Archaeology. Harper Collins, New York. ROCKMAN [WALL],DIANA,WENDY HARRIS, AND JEDLEVIN 1983 The ArchaeologicalInvestigation of the Telco Block, South Street SeaportHistoricDistrict,New York, New York. Soil Systems,Inc. National Registerof Historic Places, Washington. EXAMINING GENDER, CLASS, AND ETHNICITY IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY NEW YORK CITY ROSENWAIKE, IRA 1972 The Population History of New York City. Syracuse University Press, Syracuse,NY. ROTHSCHILD, NANA. AND ARNOLD PICKMAN 1990 The ArchaeologicalExcavationsonthe SevenHanover SquareBlock. New YorkCity Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York. ROTHSCHILD, NANA., DIANA DIZEREGA WALL,AND EUGENE BOESCH 1987 The Archaeological Investigation of the Stadt Huys Block. New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York. SALWEN, BERTAND REBECCA YAMIN 1990 The ArchaeologicalHistory of SixNineteenth Century Lots: Sullivan Street, Greenwich Village, New York City. New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, New York. SCHUYLER, ROBERT L. 1988 Archaeological Remains, Documents, and Anthropology: A Call for a New Culture History. Historical Archaeology 22( 1):36-42. SHACKEL, PAULA. 1996 Romanticism and the Protestant Ethic: Archaeology of the Early Industrial Era. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, New Orleans, LA. STANSELL, CHRISTINE 1986 City of Women: Sex and Class in New York, 17891860. Knopf, New York. STOTT, RICHARD B. 1990 Workers in the Metropolis: Class, Ethnicity, and Youthin AntebellumNew YorkCity. CornellUniversity Press, Ithaca, NY. TILLY,LOUISE A. AND JOANW. SCOTT 1978 Women, Work, and Family. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, New York. 117 TROW,JOHNF. 1880 Trow’s New York City Directory. John F. Trow, New York. UNITED STATES BUREAU OF THE CENSUS 1860 Population Schedule, Eighth Census of the United States. United States Bureau of the Census, Washington. 1870 PopulationSchedule, Ninth Censusofthe UnitedStates. United States Bureau of the Census, Washington. WALL,DIANA DIZEREGA 1991 Sacred Dinners and Secular Teas: Constructing DomesticityinMid-19thCenturyNewYork. Historical Archaeology 25 (4):69-81. 1994 The Archaeology of Gender. Plenum, New York. WETHERBEE, JEAN 1996 White Ironstone: A Collectors Guide. Antique Trade Books, Dubuque, IA. WILENTZ, SEAN 1984 ChantsDemocratic: New YorkCity andthe Riseofthe American Working Class, 1788-1850. Oxford University Press, Oxford, England. WOBST, H. MARTIN 1977 Stylistic Behavior and Information Exchange. In For the Director: Research Essays in Honor of James B. Griffin, edited by Charles E. Cleland. Michigan Anthropological Papers 61:3 17-342. Ann Arbor. YAMIN, REBECCA 1997 Tales of Five Points: Working-class Life in 19thCentury New York. Submitted to General Services Administrationfrom John Milner Associates, Inc. DIANA DIZEREGA WALL OF ANTHROPOLOGY DEPARTMENT OF NEWYORK, CUNY THECITYCOLLEGE AND CONVENT AVENUE 138th STREET NEWYORK, NY 10031