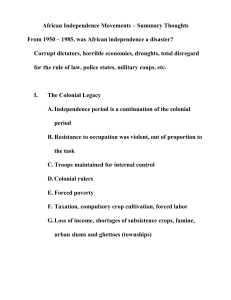

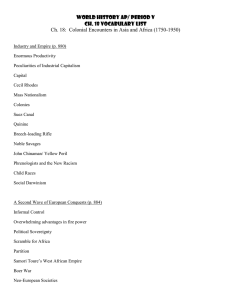

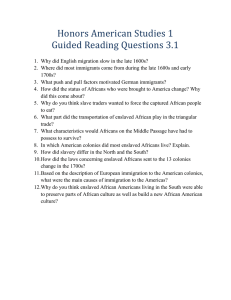

Chapter 4 colonialism and the african experiance

advertisement