Family Medicine Case study for post-menopausal woman with vaginal bleeding

advertisement

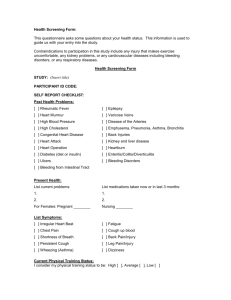

Family Medicine 17: 55-year-old post-menopausal woman with vaginal bleeding User: Sean Greig Email: sean.greig@my.rfums.org Date: April 28, 2019 11:27PM Learning Objectives The student should be able to: Define menopause and discuss common symptoms and treatment options. Develop a differential for postmenopausal bleeding. Counsel a patient regarding the differential, work-up, and follow-up plan for postmenopausal bleeding. Discuss risk factors for osteoporosis and the recommended screening for osteoporosis. Counsel patients regarding osteoporosis prevention/treatment. Discuss the recommended cancer screening for a 50-plus-year-old female. Describe the risks/benefits of hormone therapy in the postmenopausal female. Notes CA-125 is not indicated as a screening tool for ovarian cancer Knowledge Definition of Menopause Menopause is a normal process that occurs as the ovaries are depleted of follicles and produce less estrogen. It is thought to be, primarily, the lack of estrogen that leads to the majority of postmenopausal symptoms. This happens in the US at a median age of 51.3 years, between 40 and 58 years of age for most women. The natural process leading up to menopause may take several years. During the transition, it can be difficult to make a firm diagnosis. National guidelines define menopause as 12 months without a cycle. Symptoms of Menopause Hot flashes or vasomotor symptoms are the most common symptoms of menopause, and are present in up to 82% of menopausal patients. Many women will also experience symptoms of atrophic vaginitis, which can lead to vaginal dryness and dyspareunia (pain during intercourse) and urinary symptoms. Since menopause can be associated with a variety of additional problems including sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbance, mood disturbance, and concentration difficulties, it can significantly affect a woman's daily functioning and quality of life. Initial History for Vaginal Bleeding in Postmenopausal Woman Detailed description of recent bleeding and any associated symptoms. Last menstrual period. Other gynecological problems or bleeding problems. Family history of cancer, or bleeding problems. Detailed medication history, including as-needed medications and/or supplements. Review health maintenance. Screening for Women in Their 50s Without Risk Factors Mammogram There are some conflicting recommendations for breast cancer screening at this time: U.S. Preventive Service Task Force (USPSTF) Recommends biennal screening mammography for women aged 50-74 and that starting screening mammography prior to 50 years of age should be a decision that is individualized for each patient. (They found insufficient evidence to assess the benefits and harms for women over age 75.) The American Cancer Society (ACS) © 2019 Aquifer 1/9 Recommends yearly screening mammograms starting at age 45. At age 55 a person can continue to have yearly mammograms or transition to biennial mammograms. For people between 40 and 44 the ACS recommends having an informed discussion of risks and benefits with the patient. Mammograms should continue until patient’s life expectancy is less than 10 years. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Recent ACOG updates in 2017 highlight shared decision making. Patients should be offered mammogram starting at age 40 annually or biennially. Mammograms for screening should be initiated no later than age 50. Continue mammogram through age 75, then make decisions with consideration for overall health and longevity. As shared decision making is increasingly highlighted in guidelines, risk assessment tools can be helpful in individualizing recommendations. Colon cancer screening The USPSTF recommends colon cancer screening to begin at age 50 for the average risk patient. This should continue through age 75. THE USPSTF recommends against routine screening between age 76-85, but the decision on whether to screen should be individualized. They recommend against (D grade) screening after the age of 85. In response to increasing rates of colon and rectal cancer at younger ages in people born after 1980, the American Cancer Society gave a qualified recommendation in 2018 to start colon cancer screening at age 45. Options for screen are the following: Stool-based tests: Usually performed annually. Guaic-based fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT) are a bit less convenient than fecal immunochemical tests (FIT) as they require collecting three samples, whereas FIT only require one sample. Studies have found FIT testing more sensitive than gFOBT testing for colorectal cancer and adenomas. Any positive stool-based screen must be evaluated with a more definitive test, usually a colonoscopy. New DNA-based testing from a stool specimen is also an option and may be performed in conjunction with FIT testing every 1 to 3 years. Colonoscopy: Repeated every 10 years. Allows for a biopsy and removal of precancerous polyps. Is often utilized if the patient has a family history of colon cancer, a change in bowel habits, or any reported rectal bleeding. Colonoscopy is also the preferred testing for follow-up after removal of polyps. Sigmoidoscopy: Repeated every five years. This procedure only examines the rectum and sigmoid colon and so may miss polyps or lesions higher up. The advantage is that the preparation is less complicated and can be performed without anesthesia. This test may be preferred in lower medical resource areas. Pap smear Regular screening with Pap smears (cytology) has been very effective at reducing mortality from cervical cancer in screened populations. Extensive research and newer technologies have allowed for more precise guidelines for cervical cancer screening in patients of average risk. Recent recommendations from the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology call for Pap smear screening to start at age 21 and continue every three years until age 30. Preferred screening from age 30 to 65 is with HPV testing in addition to the cytology test (Pap) every five years. Screening this age group (30 to 65) with cytology alone every three years is an acceptable alternative. For people with a cervix with possible gynecologic pathology or certain risk factors - such as HIV, immunosuppression, DES exposure (while in utero), or history of cervical cancer - more frequent Pap smears may be indicated. These guidelines do not currently prohibit testing more often if the physician feels it is indicated, or if the patient requests more frequent screening. However, insurance coverage for more frequent tests in average risk patients will likely end once these new guidelines are accepted. Pap smears are not indicated for patients who have had a hysterectomy including complete removal of the cervix for non-cancer reasons and do not have a history of CIN2 or greater lesions. Screening Not Indicated for Women in Their 50's Without Risk Factors Osteoporosis Osteoporosis screening is recommended by the USPSTF for all women at, or over the age of 65, and in younger women who have equivalent fracture risks to the average white woman at age 65. The FRAX risk calculator will be discussed later on as a tool for determining risk. CA-125 level CA-125 is not indicated as a screening tool for ovarian cancer by the USPSTF. This is supported by evidence that although it may detect ovarian cancer at an earlier stage, it does not lower mortality rates. In addition, the prevalence of ovarian cancer is low, giving the test a low positive predictive value, which makes this a poor screening tool. Physical Examination for Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Pelvic Exam: Look for vulvar or vaginal lesions, signs of trauma, and cervical polyps or dysplasia. On bimanual examination, assess the size and mobility of her uterus, as a firm, fixed uterus would be concerning for uterine cancer. Neck Exam: Thyroid exam to look for goiter or nodules, as thyroid disease is one of several systemic diseases that can cause dysfunctional uterine bleeding. Skin Exam: Look for evidence of bleeding disorders, like bruises. Also, jaundice on skin exam and hepatomegaly on abdominal exam might signify an underlying acquired coagulopathy via liver disease. Symptoms & Findings of Atrophic Vaginitis © 2019 Aquifer 2/9 Symptoms: Vaginal dryness, dyspareunia, urinary symptoms and vaginal pruritis. Urinary symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infections, urinary frequency, and dysuria. Local estrogen may help women with urge incontinence and recurrent urinary tract infections. We're not sure if estrogen helps with overactive bladder, and there is conflicting evidence about its effect on stress incontinence. Vaginal pruritis: Local symptoms are usually best treated with topical estrogen in the form of either a vaginal cream or an estrogen ring, which is an estrogen impregnated ring inserted into the vagina. Physical exam findings:Smoother vaginal mucosa and cervix, related to postmenopausal changes from decreased estrogen levels. Risk Factors for Endometrial Cancer The following increase the amount of unopposed estrogen and thereby increase the risk for endometrial cancer: unopposed estrogen therapy tamoxifen (Nolvadex) - Often used in women with breast cancer and has an estrogenic effect on the female genital tract. obesity anovulatory cycles estrogen-secreting neoplasms early menarche (before age 12) late menopause (after age 52) menstrual cycle irregularities nulliparity Conversely, smoking seems to decrease estrogen exposure, thereby decreasing the cancer risk, and oral contraceptive use increases progestin levels, thus providing protection. Other risk factors for endometrial cancer include: hypertension, diabetes, and breast or colon cancer. Age is also a risk factor for endometrial cancer: The incidence of endometrial cancer more than doubles from 2.8 cases per 100,000 in those aged 30 to 34 years to 6.1 cases per 100,000 in those aged 35 to 39 years. Thus, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends endometrial evaluation in women aged 35 years and older who have abnormal uterine bleeding. When to Screen for Osteoporosis United States Preventive Services Task Force recommends osteoporosis screening for all women over the age of 65 and for younger women who have an equivalent risk to the average 65-year-old white female (9.3% ten-year risk of any osteoporotic fracture as calculated by the FRAX score). The World Health Organization has developed a tool to calculate the risk of fracture, the FRAX, which may be helpful in evaluating individual patients. The tool adjusts for gender, ethnicity, and locale. While the USPSTF found insufficient evidence to recommend screening in men, the FRAX includes calculations for men and may provide useful information about their fracture risk. Osteoporosis Risk Factors Corticosteroid use Family history of osteoporosis, especially if a first-degree relative has fractured a hip. Previous fragility fracture defined as a low-impact fracture Smoking Heavy alcohol use Lower body weight (weight < 70 kg) is the single best predictor of low bone mineral density. Obesity (B) does not put patients at risk for osteoporosis, but neither is obesity protective against osteoporosis. Caucasian race - At any given age, African-American women on average have higher bone mineral density (BMD) than white women. The USPSTF, while acknowledging that the data for non-white women is less compelling than for whites, recommends screening all women at age 65 or earlier if they have equivalent risk. Strategies to Prevent Osteoporosis Smoking cessation. Smoking increases the risk of osteoporosis. Adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D are essential to normal human physiology including bone health. A number of organizations have recommended routine supplementation of these nutrients for a variety of reasons including the prevention of osteoporosis. However, this recommendation is now being questioned. The USPSTF concludes that current evidence is insufficient to assess the balance of benefits and harms of daily supplementation with >400 IU of vitamin D3 and 1,000 mg of calcium for the primary prevention of fractures in noninstitutionalized postmenopausal women. They recommend against daily supplementation with lower doses for the primary prevention of fractures in these women because they have not demonstrated benefit at this dose, and increase the risk of nephrolithiasis. The USPSTF does not address daily dietary requirements of these nutrients; only the use of these supplements to prevent osteoporosis and certain cancers. It does illuminate the risk of the widespread calcium and vitamin D supplementation and the relative lack of good research demonstrating benefit for osteoporosis, especially in non-white populations. Pending further evidence, it is reasonable to encourage otherwise healthy women at risk for osteoporosis to consume adequate amounts of calcium and vitamin D. Most women over 50 should consume an average of 1200 mg of calcium and 800 to 1,000 IU of vitamin D daily. People of this age typically only consume about 600-700 mg of calcium and 156 IU vitamin D daily in their diet. Increasing dietary intake of © 2019 Aquifer 3/9 these nutrients should be the first line approach, but supplements may be needed when adequate dietary intake cannot be achieved and when Vitamin D deficiency is demonstrated. Vitamin D plays a major role in calcium absorption, bone health, muscle performance, balance, and risk of falling. Chief dietary sources of vitamin D include fortified milk and cereals, egg yolks, salt-water fish, and liver. Overuse of calcium and vitamin D can be harmful and patients should be advised against taking high doses of these supplements, especially without a thoughtful review of their diet and medical history. Unfortunately, patients may get conflicting information. Approximately 5% of women over 50 exceed the recommended upper intake level of 2,500 mg per day for calcium. The upper intake level for vitamin D in healthy adults is currently listed as 4,000 IU per day, but that amount is subject to change as more information becomes available. Students are encouraged to follow emerging research and recommendations for these nutrients. Lifelong weight bearing exercise (bones and muscles work against gravity as the feet and legs bear the body's weight) and muscle strengthening can improve agility, strength, posture, and balance, which may reduce the risk of falls. It may also modestly increase bone density. Examples of weight bearing exercise include walking, jogging, Tai-Chi, stair climbing, dancing, and tennis. The USPSTF recommends against using vitamin D supplements for fall prevention. Osteoporosis: Consequences, Fall Prevention, & Diagnosis Consequences Patients with osteoporosis can suffer a fracture following even minimal trauma. These fractures are most commonly of the vertebrae, the hip, distal radius and proximal humerus. The lifetime risk of fracture for a 50-year-old woman exceed her risk of developing endometrial or breast cancer. Fractures secondary to osteoporosis place an enormous burden on the elderly personally, medically, and economically. Patients with hip fractures have an average one-year mortality rate of 20 to 25 percent. Hip fractures are associated with significant loss of independence, with 15 to 25 percent of previously independent patients require nursing home placement for at least one year, and less than 30 percent of patients regain their prefracture level of function. Fall Prevention Strategies to reduce falls include: checking and correcting vision and hearing, evaluating any neurological problems, reviewing prescription medications for side effects affecting balance, and providing a checklist for improving safety at home. Diagnosis A DEXA scan is a bone densitometry study that usually looks at the lumbar spine and hip density to determine if someone has osteoporosis. This is done based on a T-score. A T-score of -1.0 to -2.5 is consistent with decreased bone density or osteopenia. Osteopenia is not a clinical diagnosis and just indicates the degree of bone decline since peak bone mass. It is usually not an indication for treatment aside from lifestyle. A T-score of less than -2.5 indicates osteoporosis. Based on the patient's risk for fracture and their T-score, we can then make recommendations for treatment of osteoporosis. The T-Score is a statistical measure that compares one person's bone mass density (BMD) in standard deviations to the average peak bone mass density in a young healthy person. A zero value is the average BMD for a young healthy person and the T-Score is then the number of standard deviations from that mean. For instance, a T-score of -1.0 indicates a bone density that is one standard deviation below the BMD of a young healthy person. This statistic is then used to classify the BMD of an individual into normal (0 to -1), osteopenia (-1 to -2.5) and osteoporosis (below -2.5). Clinical Skills How to Perform a Pelvic Exam In preparation for the pelvic exam, you elevate the head of the exam table to 30 to 45 degrees. You have the patient slide down on the exam table and help her position her feet in the stirrups. You carefully cover her legs with a sheet and ask her to relax her knees outward just beyond the angle of the stirrups. You let the patient know you are about to begin the speculum exam. When she has acknowledged this, you insert a warm, lubricated speculum. You obtain a Pap smear. You then remove the speculum and perform a bimanual exam. How to Perform Endometrial Biopsy Procedure Prior to the procedure, verify that the patient understands the procedure and the risks of: (1) bleeding or (2) rarely uterine perforation, and signs a consent form. First, have the patient get into the lithotomy position and insert a speculum. Use betadine solution to cleanse the cervix. Then, use a tenaculum (forceps with a sharp hook at the end of each jaw used for grasping tissues in surgery) to grasp the cervix on the the superior / anterior portion. Next, insert the pipelle into the os and obtain specimens from at least four different areas of the uterus. Withdraw the pipelle and place the samples into the formalin. Remove the tenaculum and speculum. The specimen is sent in formalin to the lab. In-depth review of endometrial biopsy procedure Management © 2019 Aquifer 4/9 Benefits & Risks of Hormone Therapy Benefits of Menopausal Hormonal Therapy The primary function of menopausal hormonal therapy (HT) is to treat the bothersome symptoms of menopause. Systemic estrogen is the most effective treatment for hot flashes, or vasomotor symptoms. Patients with an intact uterus must also be treated with progesterone to decrease the risk of endometrial cancer related to unopposed estrogen. Estrogen, especially when used topically, is also the most effective treatment for symptoms of atrophic vaginitis, including vaginal dryness and dyspareunia, and may improve urinary symptoms such as urge incontinence and recurrent urinary tract infections. Topical estrogens (available as an insert, cream, ring) are safe in low doses and in low doses probably do not require coverage with progesterone even in women with an intact uterus. Menopausal hormonal therapy, especially when started in the first five years after menopause, helps prevent osteoporosis by maintaining bone density. For many years, HT was used extensively for this purpose. While osteoporosis prevention may be a benefit of HT used to treat menopausal symptoms, it is not recommended as an agent for the purpose of osteoporosis prevention. The USPSTF gives this a D rating as the harms outweigh the benefits. It is still considered an option for certain women when the risk and benefit ratio favor it over other treatments. Research on the use of HT for other quality of life issues, including cognitive and depressive symptoms which commonly occur in perimenopausal and postmenopausal women, is less clear. Risks of Menopausal Hormonal Therapy While the particular risks for groups of women are still being defined, recent reviews of the available evidence have provided some key practice recommendations including: 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Combined estrogen and progestogen use beyond three years increases the risk of breast cancer. Use of unopposed systemic estrogen in females with a uterus increases endometrial cancer risk. Beginning HT after age 60 increases the risk of coronary artery disease. HT increases the risk of stroke at least for the first one to two years of use. HT for menopausal symptoms should use the lowest effective doses for the shortest possible times. Hormone therapy includes use of estrogen alone or use of estrogen combined with progesterone. It can improve health-related quality of life by improving vasomotor and atrophic symptoms caused by menopause. Routine use of HT for menopausal women decreased when research, including the Women's Health Initiative (WHI), revealed greater than expected risks associated with HT for the women in their study. But it remains an acceptable consideration in younger women before the age of 60 with few risk factors. Risks and Benefits of HRT Combined Estrogen/Progesterone Estrogen Alone Harms per 10,000 person years Harms per 10,000 person years Breast Cancer 9 Dementia 12 CAD 8 Gallbladder Disease 30 Dementia 22 Stroke 11 Gallbladder disease 21 DVT 11 Stroke 9 Incontinence 1,261 DVT 21 Incontinence 876 Benefits per 10,000 person years Benefits per 10,000 person years Diabetes -7 Breast Cancer -7 Fractures -53 Fractures -53 Colorectal Cancer -19 Diabetes -19 Table adapted from: Hormone Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Chronic Conditions in Postmenopausal Women. US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2017;318(22):2224-2233. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.18261 How to Decide When to Use Hormonal Therapy © 2019 Aquifer 5/9 Hormone therapy can be helpful for the symptoms of hot flashes and it will help delay bone loss, but it can increase the risk of breast cancer, heart attack, and stroke. Whether or not to use HT can be a difficult decision and must be individualized for each patient. There is not a right answer for all patients, and our answers change as new evidence becomes available. Our role as providers is use the best evidence we have to help patients identify their own unique risks for adverse effects from HT. Then, we can help the patient weigh the potential benefits against her personal risks. Risk factors to consider include: age family and personal history of heart disease, stroke, breast cancer, blood clots, or osteoporosis medications Quality of life plays a large role in this decision. How bothersome are the menopausal symptoms? What are the patient's preferences in taking medication vs. herbal preparations? What are her fears? Shared decision-making: In these situations where there is no right answer, the role of the physician is more of a counselor and to provide information. The responsibility of decision-making shifts to the patient, as only she can balance her quality of life against the risks she's willing to accept. In general, HT for menopausal symptoms should use the lowest effective doses for the shortest possible time which means we should discuss the risks and benefits of continuing the therapy with patients frequently. Osteoporosis Treatment Biphosphonates are potent inhibitors of bone resorption and reduce bone turnover, resulting in increase in bone mineral density. Biphosphonates have been shown to decrease the risk of vertebral and non-vertebral fractures. Alendronate (Fosamax) and risedronate (Actonel) are available in generic form, making them more affordable. Ibandronate (Boniva) is only available in trade name and the cost may be prohibitive to some patients. Zoledronic acid, an intravenous preparation, is given annually and can be used in patients who do not tolerate the oral bisphosphonates. Parathyroid hormone (Forteo) is an anabolic drug and is approved by the FDA for those with osteoporosis at high risk for fracture. It is given subcutaneously and has been shown to decrease fracture risk by 50% to 65%. It does not have demonstrated efficacy and safety beyond two years and is quite costly. Raloxifene is a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) which is used if bisphosphonates are not tolerated, but only work to prevent vertebral fractures. Calcitonin has been shown to reduce vertebral fractures, but not hip or other fractures. For most women, more effective treatments are available. Management of Hot Flashes Hormone therapy still has a role for the treatment of hot flashes and other menopausal symptoms in women at low risk for hormone-related diseases, but should be used at the minimum effective dose for the least amount of time. Other prescription medications, including the antidepressants SSRIs and SNRIs , and clonidine and gabapentin, although less effective than HT for vasomotor symptoms, can be beneficial in selected patients. The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) is the Federal Government's lead agency for scientific research on the diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine. NCCIH identified some weak evidence to support the use of hypnotherapy and mindfulness for the management of menopausal symptoms, but outlines specific concerns and recommends against the use of compounded hormones marketed as bioidentical hormone replacement therapy and against the use of DHEA. Furthermore, natural medicines, such as phytoestrogens and botanicals, have not been shown to be clearly safe and effective according to usual standards for prescription medications. Information from The National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) publication Menopausal Symptoms and Complementary Health Practices: Yoga, tai chi, qi gong, and acupuncture : There is inconsistent evidence to support their effectiveness. Phytoestrogens are found in certain plants such as soy and red clover: There is inconsistent evidence to support their use and they may be harmful in certain women, particularly those with cancer. Products made from these plants can act like estrogen in the body, but more research needs to be done before they can be widely recommended for the treatment of menopausal symptoms. They may not be safe for women at risk for hormonally related diseases. "The 2005 NIH panel found no consistent or conclusive evidence that red clover leaf extract reduces hot flashes." The scientific literature includes mixed results on soy extracts for hot flashes. Some studies find benefits, but others do not." (p6). Botanicals such as black cohosh, don quai, and kava: Black cohosh (Actaea racemosa, Cimicifuga racemosa): "Has been extensively studied for its effects on menopausal symptoms, but has not clearly shown benefit and it may not have estrogen-like effects as once thought. There is a potential relationship between black cohosh and liver problems" (p5). Dong quai (Angelica sinensis): "The only randomized clinical study of dong quai did not demonstrate benefit for hot flashes. Dong quai © 2019 Aquifer 6/9 interacts with warfarin and can cause bleeding problems" (p5). Kava (Piper methysticum): "According to the 2005 NIH panel, there is no evidence that kava decreases hot flashes, although it may decrease anxiety." There is a potential relationship between kava and liver problems (p6). Bioidentical hormone replacement therapy and DHEA: Bioidentical hormone replacement therapy is a marketing term for hormone containing medicines prepared in special pharmacies. Their content isn't regulated in the way that prescription medications are, and they have not been tested or approved by the FDA. Their safety cannot be assumed and they lack clear prescribing guidelines. DHEA is sold as a dietary supplement and is metabolized into estrogen and testosterone in the body. It has not been proven to be safe or effective and may increase the risk of hormone-related diseases. Studies Evaluation of Postmenopausal Abnormal Bleeding in Women Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) TVUS may be the most cost-effective initial test in women at low risk for endometrial cancer who have abnormal uterine bleeding. It will tell us the thickness of the endometrium. If the endometrium is less than 4 mm (some sources say < 5 mm) on ultrasound, it is reassuring and more workup may not be necessary unless the bleeding continues. Besides endometrial thickening, transvaginal ultrasonography may reveal leiomyoma (fibroids) or focal uterine masses, and may also reveal ovarian pathology. Although this imaging modality may miss endometrial polyps and submucosal fibroids, it is highly sensitive for the detection of endometrial cancer (96%) and endometrial abnormality (92%). Endometrial biopsy A histologic evaluation of the endometrium after dilation and curettage (D&C) is the traditional gold standard for the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding and for abnormal bleeding in younger women at high risk for endometrial cancer. Office-based sampling using the Pipelle device is now widely used for this purpose and has sensitivity for detecting endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women as high as 99%. An endometrial biopsy will obtain a tissue sample that will be sent to Pathology to look for evidence of endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer. Complete blood count A complete blood count might be helpful to demonstrate the absence of anemia and thrombocytopenia. An abnormal result would trigger further systemic evaluation. Thyroid-stimulating hormone level Thyroid disorders may cause abnormal uterine bleeding and are associated with an increased risk for endometrial cancer. We assess thyroid function via the thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH). This is an inexpensive test. FSH and LH level: During menopause, as aging ovarian follicles become more resistant to gonadotropin (FSH and LH) stimulation, the ovarian granulosa cells produce less inhibin. The major role of inhibin is the negative feedback regulation of the pituitary FSH secretion and synthesis. Therefore, with less inhibin production, circulating FSH and luteinizing hormone (LH) levels increase. Sufficiently elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels are sometimes used to confirm menopause, but are not useful to diagnose bleeding. Clinical Reasoning Differential of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding Most Important / Most Likely Diagnoses Cervical polyps Most common in postpartum and perimenopausal women ; rare in pre-menstrual and post-menopausal women. Although cervical polyps are rare in post-menopausal women, they can occur and if present, can cause vaginal bleeding. With or without atypia can cause bleeding. Endometrial hyperplasia Simple hyperplasia progresses to cancer in less than 5% of patients; atypical complex hyperplasia is a premalignant lesion that has a 25% probability of progressing to cancer. Therefore, careful monitoring and treatment is important with this disorder. Rare. Hormoneproducing ovarian tumors Most ovarian cancers do not cause postmenopausal bleeding or other significant symptoms, but postmenopausal bleeding is one of several symptoms associated with a higher risk for ovarian cancer (6.6 fold increased risk) . Other possible symptoms of ovarian cancer include pelvic or abdominal pain, increase in abdominal size or bloating, and difficulty eating or feeling full. The fourth most common cancer in women , and the main diagnosis that must be considered in a woman presenting © 2019 Aquifer 7/9 with postmenopausal bleeding. Endometrial cancer Also must be considered in women over the age of 35 with symptoms suggestive of anovulatory bleeding (spotting, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia). Ninety percent of patients with endometrial cancer have abnormal vaginal bleeding. Normal response to estrogen stimulation in premenopausal women. Proliferative endometrium Occasionally postmenopausal patients, particularly those in higher estrogen states, can produce a similar endometrial response. On biopsy, this condition may be hard to differentiate from simple hyperplasia. Other possible causes of abnormal uterine bleeding Other possible causes of abnormal uterine bleeding across the age spectrum are: medications (including anticoagulants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics, corticosteroids, and hormonal medications) and disorders involving the thyroid, hematologic, hepatic, adrenal, pituitary, and hypothalamic systems. References AAFP. Endometrial Biopsy, Information from your doctor. Am Fam Physician. 2001 Mar 15;63(6):1137-1138. Accessed April 29, 2017. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 141: management of menopausal symptoms. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014, Vol.123(1),202-16. Accessed January 14, 2019. Albers JR, Hull SK, Wesley RM. Abnormal Uterine Bleeding. Am Fam Physician. April 15, 2004;69:1915-26, 1931-2. Accessed April 29, 2017. American Cancer Society. American Cancer Society Guideline for Colorectal Cancer Screening. For people at average risk . Accessed December 4, 2018. American Cancer Society. Guidelines for the Early Detection of Cancer. Breast cancer . Accessed April 29, 2017. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG. Practice Bulletin No. 122. Breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Aug;118(2 Pt 1):372-82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c98e5. Accessed December 4, 2018. Assessing and Improving Measures of Hot Flashes . Accessed November 14, 2016. Bachmann GA, Nevadunsky NS. Diagnosis and Treatment of Atrophic Vaginitis. Am Fam Physician. May 15, 2000;61:3090-3096. Accessed April 29, 2017. Brunader R, Shelton D. Radiologic Bone Assessment in the Evaluation of Osteoporosis. Am Fam Physician. 2002 Apr 1;65(7):1357-1365 . Accessed April 29, 2017. Buchanan EM, Weinstein LC, Hillson C. Endometrial Cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(10):1075-1080, 1087-1088. Accessed April 29, 2017. Buchanan EM, Weinstein LC, Hillson C. Endometrial Cancer. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80(10):1075-1080, 1087-1088. Accessed December 5, 2018. Cervical Cancer Screening Guidelines for Average-Risk Women . Accessed November 14, 2016. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis . Accessed April 29, 2017. Committee on Practice Bulletins. Practice Bulletin Number 179: Breast Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening in Average-Risk Women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jul;130(1):e1-e16. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002158. Accessed on December 4, 2018. Cosman F, de Beur SJ, LeBoff MS, et al. Clinician's Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Osteoporosis Int. 2014;25(10):2359-2381. doi:10.1007/s00198-014-2794-2. Accessed April 29, 2017. Daley A, Stokes-Lampard H et al. Exercise for vasomotor menopausal symptoms. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Library, 2009 July 20;63(3):176-180. Accessed December 5, 2018. Furness, S. Roberts, H. Majoribanks, J, Lthaby, Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women and risk of endometrial hyperplasia. The Cochrane Library. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000402.pub4. Up to date: 27 Jan. 2012.. Accessed December 4, 2018. Grad R et al. Shared decision making in preventive health care: what it is and what it is not. Can Fam Physician 217. 63(9) 682- 684 . Accessed December 4, 2018. Hill D. A., Crider M., Hill S. Hormone Therapy and Other Treatments for Symptoms of Menopause. Am Fam Physician. 2016 Dec 1;94(11):884-889 . Accessed February 28, 2017. Hill DA, Hill SR, Counseling patients about hormone therapy and alternatives for menopausal symptoms, Am Fam Physician. Oct 1:82(7):801-807. Accessed April 29, 2017. Hippisley-Cox J, Coupland C. Identifying women with suspected ovarian cancer in primary care: deriviation and validation of algorithm. BMJ. 2012;344:d8009.Accessed December 5, 2018. How Do I Prevent Osteoporosis? . Accessed April 29, 2017. Jeremiah MP, Unwin BK, Greenawald MH, Casiano VE. Diagnosis and Management of Osteoporosis. Am Fam Physician. 2015 Aug 15;92(4):261-268. Accessed April 29, 2017. © 2019 Aquifer 8/9 Jillian T. Henderson, PhD; Elizabeth M. Webber, MS; George F. Sawaya, MD. Screening for Ovarian Cancer Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. AMA. 2018;319(6):595-606. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.21421. Accessed December 4, 2018. Langlois J, Nashelsky J. How useful is ultrasound to evaluate patients with postmenopausal bleeding? J Fam Pract. 2004 Dec;53(12):1005-6 . Accessed December 5, 2018. Lethaby AE, Brown J, Marjoribanks J, Kronenberg F, Roberts H, Eden J. Phytoestrogens for vasomotor menopausal symptoms; Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Library. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD001395. Accessed December 5, 2018. Maness DL, Reddy A, Harraway-Smith CL, Mitchell G, Givens V. How to best manage dysfunctional uterine bleeding. J Fam Pract. 2010 Aug;59(8):449458.Accessed December 5, 2018. McCluggage WG. My approach to the interpretation of endometrial biopsies and curettings. J Clin Path. 2006 Aug; 59(8); 801-812 .Accessed December 5, 2018. NIH. NIAMS. Osteoporosis Overview. Accessed April 29, 2017. NIH. Office of Dietary Supplements. Calcium Fact Sheet for Health Professionals . Updated: November 17, 2016. Accessed April 29, 2017. National Cancer Institute. Breast Cancer Risk Assessment Tool, http://www.cancer.gov/bcrisktool/ Updated May 16, 2011. Accessed April 29, 2017. National Institutes of Health. National Institutes of Health State-of-the-Science Conference statement: Management of menopause-related symptoms. Ann Intern Med. 2005 Jun 21;142(12):1003-1013. Accessed April 29, 2017. Nelson HD, Haney EM, et al, Screening for Osteoporosis: An Update for the USPSTF. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153 . Accessed December 5, 2018. Nucleus Medical Art. 3D Medical Animation: Endometrial Biopsy of the Uterus . Accessed April 28, 2017. Oeffinger KC, et al. American Cancer Society. Breast Cancer Screening for Women at Average Risk: 2015 Guideline Update From the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015 Oct 20;314(15):1599-614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12783. Accessed December 4, 2018. Rao S, Singh M, Parkar M, Sugumaran R. Health Maintenance for Postmenopausal Women; Am Fam Physician. 2008 Sep 1;78(5):583-591. Accessed April 29, 2017. Saslow D, Solomon D, Lawson H, et al, American Cancer Society, American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and American Society for Clinical Pathology Screening Guidelines for the Prevention and Early Detection of Cervical Cancer. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2012;16(3):1-29. Accessed December 4, 2018. Schmidt P. The 2012 hormone therapy position statement of the North American Menopause Society. Menopause, 2012 Mar;19(3):257 . Accessed December 4, 2018. Therapeutic Research Faculty. Natural Medicines in the Clinical Management of Menopausal Symptoms; Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database . Accessed April 29, 2017. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. AHRQ Prevention and Screening, Task Force working group encourages patient-provider partnership in making decisions about preventive care, February 2004. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. Colorectal Cancer: Screening. June 2016. Accessed June 7, 2017. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Final Recommendation Statement Osteoporosis to Prevent Fractures: Screening . Accessed December 4, 2018. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for Breast Cancer. January 2016 . Accessed June 7, 2017. US Preventive Services Task Force. Hormone Therapy for the Primary Prevention of Chronic Conditions in Postmenopausal Women US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA.2017;318(22):2224–2233. Accessed December 4, 2018. US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions to Prevent Falls in Community-Dwelling Older Adults US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(16):1696–1704. Accessed December 4, 2018. US Preventive Services Task Force. Vitamin D, Calcium, or Combined Supplementation for the Primary Prevention of Fractures in Community-Dwelling Adults US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2018;319(15):1592–1599. Accessed December 4, 2018. USPSTF. Vitamin D and Calcium to Prevent Fractures: Preventive Medication. February 2013 . Accessed April 29, 2017. WHO. FRAX: WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool . Accessed April 28, 2017. Zuber TJ. Endometrial Biopsy. Am Fam Physician. March 15, 2001;63:1131-35, 1137-41. Accessed April 28, 2017. © 2019 Aquifer 9/9