ASSESSMENT OF KNOWLEDGE, ATTITUDE, PRACTICE AND AVAILABILITY OF SAFETY MEASURES TOWARDS PREVENTION OF HEALTHCARE-ASSOCIATED INFECTIONS AMONG PRIMARY HEALTHCARE WORKERS IN NORTH CENTRAL ZONE, NIGERIA

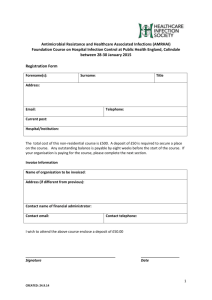

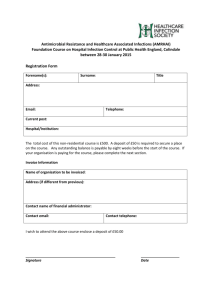

advertisement