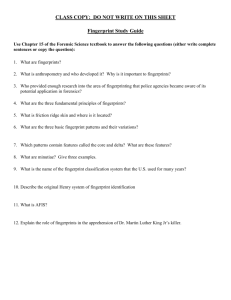

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS QUESTION & ANSWER FORUM - HELP WITH HOMEWORK The History of Fingerprints FINGERPRINT EXAMINATION Fingerprint History Chapter from The Fingerprint Sourcebook 100 Years of Fingerprint History published the Swiss Federal Police Webservant Updated 4 November 2019 Why Fingerprint Identification? Select Language Fingerprints offer a reliable means of personal identification. That is the essential explanation for fingerprints having replaced other methods of establishing the identities of persons reluctant to admit previous arrests. 1 Powered by Translate The science of fingerprint identification 5 stands out among all other forensic sciences for many reasons, including the following: Has served governments worldwide for over a century by providing accurate identification of persons. No two fingerprints have ever been found alike in many billions of human and automated computer comparisons. Fingerprints are the foundation for criminal history confirmation at police agencies worldwide. Established the first forensic professional organization, the International Association for Identification (IAI), in 1915. Established the first professional certification program for forensic scientists, the IAI's Certified Latent Print Examiner (CLPE) program in 1977. Never having claimed fingerprint experts are infallible, for over four decades the IAI's certification program has been issuing certification to those meeting stringent criteria and revoking certification for quality assurance problems such as erroneous identifications. Continues to expand as the primary method for accurately identifying persons in government record systems, with hundreds of thousands of persons added daily to fingerprint repositories worldwide. For more than a century, has remained the most commonly used forensic evidence worldwide - in most jurisdictions fingerprint examination cases match or outnumber all other forensic examination casework combined. Fingerprints harvested from crime "scenes lead to more suspects and generate more evidence in court than all other forensic laboratory techniques combined.2" Is relatively inexpensive for solving crime. Expense is an important factor because agencies must balance investigative resources to best satisfy timeliness and thoroughness, without sacrificing accuracy. For example, DNA is as ubiquitous as fingerprints at many crime scenes, but can cost 100 to 400 times more than fingerprint analysis for each specimen, and can require additional months or years before analysis is complete. Thus, while both fingerprints and DNA are typically harvested from serious crimes such as sexual assault and murder, fingerprints are often the primary evidence collected from lesser crimes such as burglaries and vehicle break-ins. Other visible human characteristics, such as facial features, tend to change considerably with age, but fingerprints are relatively persistent. Barring injuries or surgery causing deep scarring, or diseases such as leprosy damaging the formative layers of friction ridge skin, finger and palm print features have never been shown to move about or change their unit relationship throughout the life of a person (and injuries, scarring and diseases tend to exhibit telltale indicators of unnatural change). In earlier civilizations, branding or maiming (cutting off hands) were used to mark persons as criminals. The thief was deprived of the hand which committed the thievery. Ancient Romans employed the tattoo needle to identify and prevent desertion of mercenary soldiers from their ranks. Before the mid-1800s, law enforcement officers with extraordinary visual memories, so-called "camera eyes," identified previously arrested offenders by sight alone. Photography lessened the burden on memory, but was not the answer to the criminal identification problem. Personal appearances change. Around 1870, French anthropologist Alphonse Bertillon devised a system to measure and record the dimensions of certain bony parts of the body. These measurements were reduced to a formula which, theoretically, would apply only to one person and would not change during his/her adult life. Bertillon also invented the concept of arrest photographs or mugshots made at the same time bodily measurements and fingerprints were recorded. The Bertillon System was generally accepted for thirty years, however the anthropometric measurement system never recovered from the events of 1903, when a man named Will West was sentenced to the US Penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas. It was discovered there was already a prisoner at the penitentiary, whose Bertillon measurements were nearly the same, and his name was William West. Upon investigation, there were indeed two men who looked very similar. Their names were William and Will West. Their Bertillon measurements were similar enough to identify them as the same person. However, fingerprint comparisons quickly and correctly determined biometrics (fingerprints and face) were from two different people. (According to prison records publicized years later, the West men were apparently identical twin brothers and each had a record of correspondence with the same immediate family relatives.) Prehistoric Ancient artifacts with carvings similar to friction ridge skin have been discovered in many places throughout the world. Picture writing of a hand with ridge patterns was discovered in Nova Scotia. In ancient Babylon, fingerprints were used on clay tablets for business transactions. BC 200s - China Chinese records from the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) include details about using handprints as evidence during burglary investigations. Clay seals bearing friction ridge impressions were used during both the Qin and Han Dynasties (221 BC - 220 AD). AD 1400s - Persia The 14th century Persian book "Jaamehol-Tawarikh" (Universal History), attributed to Khajeh Rashiduddin Fazlollah Hamadani (1247-1318), includes comments about the practice of identifying persons from their fingerprints. 1600s In a "Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London" paper in 1684, Dr. Nehemiah Grew was the first European to publish friction ridge skin observations. 1685 - Bidloo Dutch anatomist Govard Bidloo's 1685 book, "Anatomy of the Human Body" included descriptions of friction ridge skin (papillary ridge) details. Table 4 from "Anatomy of the Human Body." In 1686, Marcello Malpighi, an anatomy professor at the University of Bologna, noted fingerprint ridges, spirals and loops in his treatise. A layer of skin was named after him; "Malpighi" layer, which is approximately 1.8 mm thick. No mention of friction ridge skin uniqueness or permanence was made by Grew, Bidloo or Malpighi. 1788 - Mayer German anatomist and doctor J. C. A. Mayer wrote the book Anatomical Copper-plates with Appropriate Explanations containing drawings of friction ridge skin patterns. Mayer wrote, “Although the arrangement of skin ridges is never duplicated in two persons, nevertheless the similarities are closer among some individuals. In others the differences are marked, yet in spite of their peculiarities of arrangement all have a certain likeness” (Cummins and Midlo, 1943, pp 12–13). Mayer was the first to declare that friction ridge skin is unique. 1823 - Purkinje In 1823, Jan Evangelista Purkinje, anatomy professor at the University of Breslau, published his thesis discussing nine fingerprint patterns. Purkinje also made no mention of the value of fingerprints for personal identification. Purkinje is referred to in most English language publications as John Evangelist Purkinje. 1856 - Welcker German anthropologist Hermann Welcker of the University of Halle, studied friction ridge skin permanence by printing his own right hand in 1856 and again in 1897, then published a study in 1898. 1858 - Herschel The English first began using fingerprints in July 1858 when Sir William James Herschel, Chief Magistrate of the Hooghly District in Jungipoor, India, first used fingerprints on native contracts. On a whim, and without thought toward personal identification, Herschel had Rajyadhar Konai, a local businessman, impress his hand print on a contract. The purpose was to "... to frighten [him] out of all thought of repudiating his signature." The native was suitably impressed and Herschel made a habit of requiring palm prints--and later, simply the prints of the right Index and Middle fingers--on every contract made with the locals. Personal contact with the document, they believed, made the contract more binding than if they simply signed it. Thus, the first wide-scale, modern-day use of fingerprints was predicated, not upon scientific evidence, but upon superstitious beliefs. Herschel's fingerprints recorded over a period of 57 years As his fingerprint collection grew, however, Herschel began to note that the inked impressions could, indeed, prove or disprove identity. While his experience with fingerprinting was admittedly limited, Sir William Herschel's private conviction that all fingerprints were unique to the individual, as well as permanent throughout that individual's life, inspired him to expand their use. 1863 - Coulier Professor Paul-Jean Coulier, of Val-de-Grâce in Paris, published his observations that (latent) fingerprints can be developed on paper by iodine fuming, explaining how to preserve (fix) such developed impressions and mentioning the potential for identifying suspects' fingerprints by use of a magnifying glass. 3, 4 1877 - Taylor American microscopist Thomas Taylor proposed that finger and palm prints left on any object might be used to solve crimes. The July 1877 issue of The American Journal of Microscopy and Popular Science included the following description of a lecture by Taylor: Hand Marks Under the Microscope. - In a recent lecture, Mr. Thomas Taylor, microscopist to the Department of Agriculture, Washington, D.C., exhibited on a screen & view of the markings on the palms of the hands and the tips of the fingers, and called attention to the possibility of identifying criminals, especially murderers, by comparing the marks of the hands left upon any object with impressions in wax taken from the hands of suspected persons. In the case of murderers, the marks of bloody hands would present a very favorable opportunity. This is a new system of palmistry. 1870s-1880 - Faulds During the 1870s, Dr. Henry Faulds, the British Surgeon-Superintendent of Tsukiji Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, took up the study of "skin-furrows" after noticing finger marks on specimens of "prehistoric" pottery. A learned and industrious man, Dr. Faulds not only recognized the importance of fingerprints as a means of identification, but devised a method of classification as well. In 1880, Faulds forwarded an explanation of his classification system and a sample of the forms he had designed for recording inked impressions, to Sir Charles Darwin. Darwin, in advanced age and ill health, informed Dr. Faulds that he could be of no assistance to him, but promised to pass the materials on to his cousin, Francis Galton. Also in 1880, Dr. Henry Faulds published an article in the Scientific Journal, "Nature" (nature). He discussed fingerprints as a means of personal identification, and the use of printers ink as a method for obtaining such fingerprints. He is also credited with the first fingerprint identification of a greasy fingerprint left on an alcohol bottle. 1882 - Thompson In 1882, Gilbert Thompson of the U.S. Geological Survey in New Mexico, used his own thumb print on a document to help prevent forgery. This is the first known use of fingerprints in the United States. Click the image below to see a larger image of an 1882 receipt issued by Gilbert Thompson to "Lying Bob" in the amount of 75 dollars. 1882 - Bertillon Alphonse Bertillon, a clerk in the Prefecture of Police of at Paris, France, devised a system of classification, known as anthropometry or the Bertillon System, using measurements of parts of the body. Bertillon's system included measurements such as head length, head width, length of the middle finger, length of the left foot; and length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger. Bertillon also established a system of photographing faces - what became known as mugshots. In 1888 Bertillon was made Chief of the newly created Department of Judicial Identity where he used anthropometry as the primary means of identification. He later introduced Fingerprints, but relegated them to a secondary role in the category of special marks. 1883 - Mark Twain (Samuel L. Clemens) In Mark Twain's book, "Life on the Mississippi", a murderer was identified by the use of fingerprint identification. In a later book, "Pudd'n Head Wilson", there was a dramatic court trial including fingerprint identification. A movie was made from this book in 1916 and a made-for-TV movie in 1984. 1888 - Galton Sir Francis Galton, British anthropologist and a cousin of Charles Darwin, began his observations of fingerprints as a means of identification in the 1880's. 1891 - Vucetich Juan Vucetich, an Argentine Police Official, began the first fingerprint files based on Galton pattern types. At first, Vucetich included the Bertillon System with the files. Right Thumb Impression and Signature of Juan Vucetich 1892 - Alvarez & Galton At Buenos Aires, Argentina in 1892, Inspector Eduardo Alvarez made the first criminal fingerprint identification. He was able to identify Francisca Rojas, a woman who murdered her two sons and cut her own throat in an attempt to place blame on another. Her bloody print was left on a door post, proving her identity as the murderer. Alvarez was trained by Juan Vucetich. Francisca Rojas' Inked Fingerprints Sir Francis Galton published his book, "Finger Prints" in 1892, establishing the individuality and permanence of fingerprints. The book included the first published classification system for fingerprints. In 1893, Galton published the book "Decipherment of Blurred Finger Prints," and 1895 the book "Fingerprint Directories." Galton's primary interest in fingerprints was as an aid in determining heredity and racial background. While he soon discovered that fingerprints offered no firm clues to an individual's intelligence or genetic history, he was able to scientifically prove what Herschel and Faulds already suspected: that fingerprints do not change over the course of an individual's lifetime, and that no two fingerprints are exactly the same. According to his calculations, the odds of two individual fingerprints being the same were 1 in 64 billion. Galton identified the characteristics by which fingerprints can be identified. A few of these same characteristics (minutia) are basically still in use today, and are sometimes referred to as Galton Details. 1897 - Haque & Bose On 12 June 1897, the Council of the Governor General of India approved a committee report that fingerprints should be used for the classification of criminal records. Later that year, the Calcutta (now Kolkata) Anthropometric Bureau became the world's first Fingerprint Bureau. Working in the Calcutta Anthropometric Bureau (before it became the Fingerprint Bureau) were Azizul Haque (shown above) and Hem Chandra Bose. Haque and Bose are the two Indian fingerprint experts credited with primary development of the Henry System of fingerprint classification (named for their supervisor, Edward Richard Henry). The Henry classification system is still used in English-speaking countries (primarily as the manual filing system for accessing paper archive files that have not been scanned and computerized). 1900 - E.R. Henry The United Kingdom Home Secretary Office conducted an inquiry into "Identification of Criminals by Measurement and Fingerprints." Mr. Edward Richard Henry (later Sir ER Henry) appeared before the inquiry committee to explain the system published in his recent book "The Classification and Use of Fingerprints." The committee recommended adoption of fingerprinting as a replacement for the relatively inaccurate Bertillon system of anthropometric measurement, which only partially relied on fingerprints for identification. 1901 The Fingerprint Branch at New Scotland Yard (Metropolitan Police) was created in July 1901. It used the Henry System of Fingerprint Classification. 1902 Dr. Henry Pelouze de Forest pioneered the idea for the first American fingerprinting file. The fingerprints were used to screen New York City civil service applicants. 1903 In 1903, the New York City Civil Service Commission, the New York State Prison System and the Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas were using fingerprinting. In 1903, Will and William West's fingerprints were compared at Leavenworth Penitentiary after they were found to have very similar Anthropometric measurements. 1904 The use of fingerprints began at the St. Louis Police Department. They were assisted by a Sergeant from Scotland Yard who had been on duty at the St. Louis World's Fair Exposition guarding the British Display. Sometime after the St. Louis World's Fair, the International Association of Chiefs of Police (IACP) created America's first national fingerprint repository, called the National Bureau of Criminal Identification. 1905 U.S. Army begins using fingerprints. U.S. Department of Justice forms the Bureau of Criminal Identification in Washington, DC to provide a centralized reference collection of fingerprint cards. Two years later the U.S. Navy started, and was joined the next year by the Marine Corp. During the next 25 years more and more law enforcement agencies join in the use of fingerprints as a means of personal identification. Many of these agencies began sending copies of their fingerprint cards to the National Bureau of Criminal Identification, which was established by the International Association of Police Chiefs. 1907 U.S. Navy begins using fingerprints. U.S. Department of Justice's Bureau of Criminal Identification moves to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary where it is staffed at least partially by inmates. 1908 U.S. Marine Corps begins using fingerprints. 1910 In 1910, Frederick Brayley published the first American textbook on fingerprints, "Arrangement of Finger Prints, Identification, and Their Uses." 1914 - Electronic Encoding of Fingerprints - Denmark Police In 1914, Hakon Jörgensen with the Copenhagen, Denmark Police lectures about the distant identification of fingerprints at the International Police Conference in Monaco. The process involved encoding fingerprint features for transmission to distant offices facilitating identification through electronic communications. In 1916, the book "Distant Identification" is published and used in Danish police training. The NIST (NBS) 1969 technical note reviewing Jörgensen's system is online here. The 1922 English version of a book describing Jörgensen's "Distant Identification" system is online here. 1915 Inspector Harry H. Caldwell of the Oakland, California Police Department's Bureau of Identification wrote numerous letters to "Criminal Identification Operators" in August 1915, requesting them to meet in Oakland for the purpose of forming an organization to further the aims of the identification profession. In October 1915, a group of twenty-two identification personnel met and initiated the "International Association for Criminal Identification" In 1918, the organization was renamed to the International Association for Identification (IAI) due to the volume of non-criminal identification work performed by members. Sir Francis Galton's right index finger appears in the IAI logo. The IAI's official publication is the Journal of Forensic Identification. The IAI's 100th annual educational conference was held in Sacramento, California, near the IAI's original roots. 1918 Edmond Locard wrote that if twelve points (Galton's Details) were the same between two fingerprints, it would suffice as a positive identification5. Locard's twelve points seems to have been based on an unscientific "improvement" over the eleven anthropometric measurements (arm length, height, etc.) used to "identify" criminals before the adoption of fingerprints. 1924 In 1924, an act of congress established the Identification Division of the FBI. The IACP's National Bureau of Criminal Identification and the US Justice Department's Bureau of Criminal Identification consolidated to form the nucleus of the FBI fingerprint files. During the decades since, the FBI's fingerprint national fingerprint support (both through Criminal Justice Information Services and the FBI Laboratory) has been indispensable in supporting American law enforcement. 1940s By the end of World War II, most American fingerprints experts agreed there was no scientific basis for a minimum number of corresponding minutiae to determine an "identification" and the twelve point rule was dropped from the FBI publication, "The Science of Fingerprints." 1946 By 1946, the FBI had processed over 100 million fingerprint cards in manually maintained files; and by 1971, 200 million fingerprint cards. With the introduction of automated fingerprint identification system (AFIS) technology, the files were later split into computerized criminal files and manually maintained civil files. Many of the manual files were duplicates though, the records actually represented somewhere in the neighborhood of 25 to 30 million criminals, and an unknown number (tens of millions) of individuals represented in the civil files. 1973 The International Association for Identification Standardization Committee authored a resolution stating that each identification is unique and no valid basis exists to require a minimum number of matching points in two friction ridge impressions to establish a positive identification. The resolution was approved by members at the 1973 annual conference. 1974 The Fingerprint Society In 1974, four employees of the Hertfordshire (United Kingdom) Fingerprint Bureau contacted fingerprint experts throughout the UK and began organization of that country's first professional fingerprint organization, the National Society of Fingerprint Officers. The organization initially consisted of only UK experts, but quickly expanded to international scope and was renamed The Fingerprint Society in 1977. The initials F.F.S. behind a fingerprint expert's name indicates they are recognized as a Fellow of the Fingerprint Society. The Society hosts annual educational conferences with speakers and delegates attending from many countries. In 2017, The Fingerprint Society merged with The Chartered Society of Forensic Sciences (CSFS) has since been known as the CSFS Fingerprint Division 1977 On 1 August 1977 at New Orleans, Louisiana, delegates to the 62nd Annual Conference of the International Association for Identification (IAI) voted to establish the world's first certification program for fingerprint experts. Since 1977, the IAI's Latent Print Certification Board has proficiency tested thousands of applicants, and periodically proficiency tests all IAI Certified Latent Print Examiners (CLPEs). Contrary to claims (since the 1990s) that fingerprint experts claim their body of practitioners never make erroneous identifications, the Latent Print Certification program proposed, adopted, and active since 1977 has specifically recognized such mistakes sometimes occur and must be addressed. During the past three decades, CLPE status has become a prerequisite for journeyman fingerprint expert positions in many US state and federal government forensic laboratories. IAI CLPE status is considered by many identification professionals to be a measurement of excellence. 1995 At the International Symposium on Latent Fingerprint Detection and Identification, conducted by the Israeli National Police Agency, at Neurim, Israel, June, 1995, the Neurim Declaration was issued. The declaration, (authored by Pierre Margot and a fingerprint expert from the US Army Crime Lab), states "No scientific basis exists for requiring that a pre-determined minimum number of friction ridge features must be present in two impression in order to establish a positive identification." The declaration was unanimously approved by all present, and later, signed by 28 persons from the following 11 countries: Australia, Canada, France, Holland, Hungary, Israel, New Zealand, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States. 2012 INTERPOL's Automated Fingerprint Identification System repository exceeds 150,000 sets of fingerprints for important international criminal records from 190 member countries. Over 170 countries have 24 x 7 interface ability with INTERPOL expert fingerprint services. 2015 - The International Association for Identification celebrated it's 100th Anniversary 2019 - America's Largest Databases The Department of Homeland Security's Office of Biometric Identity Management (OBIM was formerly US-VISIT), contains over 120 million persons' fingerprints, many in the form of two-finger records. The US Visit Program has been migrating from two flat (not rolled) fingerprints to ten flat fingerprints since 2007. "Fast capture" technology currently enables recording of ten simultaneous fingerprint impressions in as little as 15 seconds per person. As of July 2018, the FBI's Next Generation Identification (NGI) conducts more than 300,000 tenprint record searches per day against more than 140 million computerized fingerprint records (both criminal and civil applicant records). The 300,000 daily fingerprint searches support 18,000 law enforcement agencies and 16,000 non-law enforcement agencies7. At 70% more accurate that the FBI's previous version of automated latent print technology, NGI is the FBI's most valuable service to American law enforcement, providing accurate and rapid fingerprint identification support. FBI civil fingerprint files in NGI (mainly federal employees) have become searchable by all US law enforcement agencies in recent years. Many enlisted military service member fingerprint cards received after 1990, and most (officer, enlisted and civilian) military-related fingerprint cards received after 19 May 2000, have been computerized and are searchable. The FBI is continuing to expand their automated identification activities to include other biometrics such as palm, face, and iris. Face search capabilities in NGI are a reality for many US law enforcement agencies accessing NGI, and several are participating in iris pilot projects. All US states and many large cities have their own AFIS databases, each with a subset of fingerprint records that is not stored in any other database. Many also store and search palmprints. Law enforcement fingerprint interface standards are important to enable sharing records and reciprocal searches to identify criminals. International Sharing Many European nations currently leverage multiple fingerprint information sharing operations, including the following: Schengen Information System (SIS); Visa Information System (VIS); European Dactyloscopy (EURODAC); and Europol. Additionally, a biometric-based Entry Exit System (EES) is in planning stages. Many other countries exchanges searches/fingerprint records in a similar manner as Europe, with automated and non-automated interfaces existing in accordance with national/international privacy laws and the urgency/importance of such searches. 2019 - World's Largest Database The Unique Identification Authority of India is the world's largest fingerprint (and largest multi-modal biometric) system using fingerprint, face and iris biometric records. India's Unique Identification project is also known as Aadhaar, a word meaning "the foundation" in several Indian languages. Aadhaar is a voluntary program, with the goal of providing reliable national ID documents to most of estimated India's 1.25 billion residents. With a biometric database many times larger than any other in the world, Aadhaar's ability to leverage automated fingerprint and iris modalities (and potentially automated face recognition) enables rapid and reliable automated searching and identification impossible to accomplish with fingerprint technology alone, especially when searching children and elderly residents' fingerprints (children are fingerprinted and photographed as young as age 5). As of January 2017, the Authority has issued more than 1.11 billion (more than 111 crore) Aadhaar numbers. _______________________________________________________________________________ Like most attempts to document history, this page strives to balance what happened first with what matters. The result does not mean this fingerprint history page (or any other historical account) is complete or entirely accurate. This page is maintained by an American fingerprint expert, biased by English language scientific journals and historical publications. Other countries' experts (especially from non-English language countries) may have completed important fingerprint-related scientific accomplishments before the above dates. Please email recommended changes and citations for those modifications to ed "at" onin.com. Some of the above wording is credited to the writing of Greg Moore, from his previous fingerprint history page at http://www.brawleyonline.com/consult/history.htm (no longer there). Also, David L. von Minden, Ph.D. helped correct typos his students kept cutting and pasting into their homework. 1 Interpol, "General Position on Fingerprint Evidence," by the Interpol European Expert Group on Fingerprint Identification (accessed March 2010 at www.interpol.int/public/Forensic/fingerprints/WorkingParties/IEEGFI/ieegfi.asp#val). 2 3 Coulier, P.-J. Les vapeurs d'iode employees comme moyen de reconnaitre l'alteration des ecritures. In L'Annee scientiJique et industrielle; Figuier, L. Ed.; Hachette, 1863; 8, pp 157-160 at http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k7326j (as of March 2010). Margot, Pierre and Quinche, Nicolas, "Coulier, Paul-Jean (1824-1890): A Precursor in the History of Fingermark Detection and Their Potential Use for Identifying Their Source (1863)", Journal of forensic identification, 60 (2), March-April 2010, pp. 129-134, (published by the International Association for Identification). 4 As of 2016, the term positive identification (meaning absolute certainty) has been replaced in reports and testimony by most agencies/experts with more accurate terminology, including variations of wording such as the following: 5 Examination and comparison of similarities and differences between the impressions resulted in the opinion there is a much greater support for the impressions originating from the same source than there is for them originating from different sources. A related 2014 paper titled "Individualization is dead, long live individualization! Reforms of reporting practices for fingerprint analysis in the United States" by Simon Cole, Professor at University of California, Irvine is linked here. Herschel information is from a Fingerprint Identification presentation by T. Dickerson Cook at the annual meeting of the Texas Division, International Association for Identification, at Midland, Texas on 9 August 1954 (documented in Identification News, April 1964, pages 5-10). 6 7 Includes details from an August 2018 presentation by FBI Biometric Services/NGI Section Chief William G. McKinley at the International Association for Identification's annual educational conference. William and Will West images courtesy of Joshua L. Connelly, CLPE, whose research into fingerprint history archives continues to enlighten the friction ridge community. 8 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS FINGERPRINT EXAMINATION Fingerprinting Merit Badge Pages Webservant