See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233157862

Ethical Dilemmas for Clinical Psychologists in Conducting

Qualitative Research

Article in Qualitative Research in Psychology · January 2012

DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2012.630636

CITATIONS

15

2 authors:

Andrew R Thompson

The University of Sheffield

122 PUBLICATIONS 2,413 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

READS

1,511

Kate Russo

Queen's University Belfast

18 PUBLICATIONS 62 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Qualitative Research Methods in Mental Health and Psychotherapy: A Guide for Students and Practitioners View project

Learning Disability: Empowerment and Understanding View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Kate Russo on 19 July 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

This article was downloaded by: [Andrew R. Thompson]

On: 14 December 2011, At: 12:47

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Qualitative Research in Psychology

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uqrp20

Ethical Dilemmas for Clinical

Psychologists in Conducting Qualitative

Research

Andrew R. Thompson

a

& Kate Russo

b a

University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

b

Queens University Belfast, Belfast, UK

Available online: 14 Dec 2011

To cite this article: Andrew R. Thompson & Kate Russo (2012): Ethical Dilemmas for Clinical

Psychologists in Conducting Qualitative Research, Qualitative Research in Psychology, 9:1, 32-46

To link to this article:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2012.630636

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Qualitative Research in Psychology , 9:32–46, 2012

Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 1478-0887 print/1478-0895 online

DOI: 10.1080/14780887.2012.630636

Ethical Dilemmas for Clinical Psychologists in

Conducting Qualitative Research

ANDREW R. THOMPSON

1

AND KATE RUSSO

2

1 University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK

2 Queens University Belfast, Belfast, UK

Clinical psychologists often use qualitative methods to explore sensitive topics with vulnerable individuals, yet there has been little discussion of the specific ethical issues involved. For clinicians conducting qualitative research, there are likely to be ethical dilemmas associated with being both a researcher and a practitioner. We argue that this overarching issue frames all other ethical issues raised. This article provides an overview of the range of ethical issues that have been discussed in general in relation to qualitative research and considers the specific nature of these in relation to the discipline of clinical psychology. Such issues will be exemplified by reference to some of our own research and practice and the extant literature. We conclude with some suggestions for good practice, although our aim is to trigger debate rather than to establish prescriptive guidelines.

Keywords : clinical psychology; confidentiality; consent; dual-role; ethics; qualitative research

Introduction

The ability to be self-aware and to be able to reflect in relation to ethical dilemmas is a core competency of the clinical psychologist as both a scientist and as a reflective practitioner. However, many research participants, and some researchers, may have a limited understanding of what the term “ethics” actually means (Graham, Grewal & Lewis 2007).

In addition, qualitative methods have sometimes mistakenly been viewed as being “more ethical” than quantitative methods, perhaps because they are assumed to place greater emphasis on moral subjectivity. However, such “qualitative ethicism” (Hammersley 1999) is dangerous because it risks obscuring complex moral dilemmas that need to be actively reflected upon. Thus the aim in writing this article is to raise awareness of the specific ethical dilemmas that clinical psychologists may face when conducting qualitative research and to encourage reflection and discussion of how best to address these issues in the context of the discipline’s broader set of values.

To contextualise this, we will first say something about the nature of clinical psychology and then describe the qualitative research we have undertaken ourselves whilst employed within this role. The British Psychological Society (BPS) states that “clinical psychologists aim to reduce psychological distress and to enhance and promote psychological well-being by the systematic application of knowledge derived from psychological

Correspondence: Dr. Andrew R. Thompson, Reader in Clinical Psychology, Clinical Training

Research Director, Clinical Psychology Unit, Department of Psychology, University of Sheffield,

302 Western Bank, Sheffield, S10 2TN, United Kingdom. E-mail: a.r.thompson@sheffield.ac.uk

32

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research 33 theory and research” (BPS 2008a, p. 8). Both authors of this article are clinical psychologists working in split clinical and academic posts and contribute to the training of clinical psychologists, and both therefore have an active role in undertaking and supervising research in health settings. Andrew Thompson is employed in a health setting and has undertaken research largely in relation to chronic illness, particularly disfigurement

(e.g., Thompson, Kent & Smith 2002) and also in relation to the practice of mental health clinicians (e.g., Thompson, Donnison et al. 2008). Kate Russo is employed in a paediatric health setting, and her research has focused primarily on family adjustment to cystic fibrosis (Russo & Hogg 2004), specifically in relation to inpatient care and cross infection issues

(e.g., Russo, Donnelly & Reid 2006, 2008).

Highlighting, where appropriate, moral dilemmas that we have experienced in conducting research in clinical settings, we aim to outline the core ethical dilemmas associated with holding multiple roles as a clinical psychologist and as researcher. We recognise that many of these issues will be pertinent to other professionals and other branches of psychology. We will discuss these dilemmas within the context of the existing professional principles identified in the Code of Ethics and Conduct of the British Psychological Society

(British Psychological Society 2006).

What Are Ethics?

Ethics are moral principles and values which guide action. Such principles are frequently enshrined in codes of conduct developed for specific settings and professions, such as the four principles of respect, competence, responsibility and integrity laid down by the

BPS to cover the activities of being a professional psychologist (BPS Code of Ethics and

Conduct 2006). The concept of research ethics then focuses on the moral principles specifically needed to guide scientific investigation. Moral principles ultimately originate from philosophical positions, the most widely known and simplest of these being the distinction between deontological and consequentialist positions. Francis (2009) provides a useful summary of the philosophical positions in ethics as relevant to psychologists, detailed discussion of which is beyond the scope of this article. To simplify, the deontological position emphasises that the morality of an action must be assessed on its intrinsic qualities, independent of its consequences and outcome. This is contrasted with the utilitarian position, which places emphasis on the merits of the outcome. Both of these positions are evident in most modern ethical codes.

Researchers must understand and adhere to their professional codes and the codes of healthcare providers (Department of Health 2001, 2005; National Research Ethics Service

2001). However, ethical decision making is not a simple matter of slavishly following guidelines; instead, “variable factors are involved” (BPS Code of Ethics and Conduct 2006, p. 5). Each ethical dilemma is unique and has to be considered within its own social, theoretical and political milieu. This position itself is also derived from a long philosophical tradition that can be linked back to the contextual stance of Aristotle (see Brinkmann &

Kvale 2008 for further discussion). In line with this, we will shortly explore the ethical issues for clinical psychologists in conducting qualitative research against the backdrop of healthcare settings, where the focus is often on exploring sensitive issues with vulnerable participants. The majority of clinical psychology qualitative research has involved the use of interviews and we shall focus mainly upon this type of methodology in this article.

Ethical Scrutiny

There have been considerable developments in the guidance and regulation of healthcare research over the last few years. For example, in the United Kingdom, the Department of

34 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo

Health, partly in response to a number of research scandals (e.g., at Alder Hey Hospital), launched the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (Department of Health 2001, 2005). This framework covers all aspects of research including ethical scrutiny, financial probity, health and safety and the responsibilities of all stakeholders.

In addition, the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) was launched in 2001 to provide a standardised process for the ethical scrutiny of healthcare research in the United Kingdom

(NRES 2001).

It has been suggested that the application of rigid ethical frameworks and procedures has contributed to an objectification of ethics, which risks ethical issues being seen simply as a set of procedural tasks, before the “real” research starts (Small 2001). Several authors have questioned what they see as the constraining and paternalistic nature of biomedical ethical procedures and commented that such procedures are a form of “ethics creep” into social research (Haggerty 2004, p. 391; Holland 2007). NHS governance and ethics guidelines remain focused upon the issues associated with clinical trials, and as such it has been argued that they are not entirely appropriate for qualitative research or indeed social science research in general (BPS 2005; Haggerty 2004). Although there is now a focus upon

NHS ethics and governance committees to have qualitative research expertise and to work closely together to remove barriers to research (Department of Health 2007), there remain differences between NHS Trusts in relation to the processes involved in research governance. More particularly there remain unsuitable procedures for qualitative research that can hinder social science research.

Whilst we have sympathy for the “ethics creep” argument in relation to the appropriateness of existing principles for guiding clinical psychologists engaging in NHS qualitative research, it is also important to note that few alternative frameworks have been suggested. There is a risk that focusing upon what is unhelpful detracts from generating useful guidance. To generate useful discussion, we will now turn to the ethical issues that clinical psychologists are likely to face in conducting qualitative research.

What Are the Ethical Issues for Qualitative Researchers?

There have been two recent literature reviews conducted in relation to the ethical issues associated with qualitative research (Graham, Lewis & Nicolaas 2006; Allmark et al.

2009). They both note that there are a large number of discussion papers but few empirical studies. They identify several overlapping themes, including confidentiality and privacy, informed consent, harm, dual-role and overinvolvement and politics and power . The majority of these are fundamental moral concerns, which are equally applicable across disciplines and both quantitative and qualitative approaches.

The difference between the dilemmas for quantitative and qualitative researchers, as identified in these themes, is associated with the degree of interaction between participant and researcher. It is this relationship that has led some to see qualitative research as “saturated with ethical issues” (Brinkmann & Kvale 2008, p. 263). We would argue that, for clinical psychologists, this saturation occurs in the context of our primary role as healthcare practitioners / clinicians providing individual, group, and organisational intervention and consultation.

Clinical Psychologists — Multiple Roles and Ethical Dilemmas

Empirical studies across a number of professions have demonstrated that barriers to acting ethically commonly occur when professionals wear “too many hats” (Seider, Davis &

Gardner 2007). Issues associated with occupying multiple roles are central to the ethical

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research 35 dilemmas that are likely to arise for clinical psychologists, as well as for other applied researchers working in health settings, and this overarching issue frames all of the other ethical issues highlighted by recent reviews. Multiple role issues include not only direct overlaps of role as, for example, where a clinical psychologist conducts research within their employing organisation or with patients that they have worked with, but also includes issues associated with less direct overlap between the role of clinical psychologist per se and that of qualitative researcher. One obvious overlap is between the research interviewer and clinician.

The similarities and differences between therapy and qualitative interviews and the ethical dilemmas posed by this have been discussed by others to some extent (Brinkmann &

Kvale 2005, 2008) but have not been specifically related to the research and therapeutic practice of clinical psychologists. Studies that have explored the ethical issues present in psychotherapeutic practice demonstrate that therapists themselves are very concerned about ethical issues associated with “dual relationships” such as overinvolvement or sexual encounters (e.g., Lindsay & Colley 1995), whereas people receiving therapy maybe more concerned with confidentiality (Fennig et al. 2005) and autonomy (Martindale,

Chambers & Thompson 2009). Much less has been written about issues associated with dual relationships connected to the role of clinician-researcher. Yet qualitative research by its nature involves close engagement with participants, therefore providing the context for similar boundary issues to arise.

Clearly, clinical psychologists undertaking qualitative research need to reflect on the different purposes of the therapeutic encounter and the research encounter—one is a building block for longer-term contact, with a mandate of facilitating change, and the other has at its centre the aim of gaining information (which may often not be focused on the needs of the individual participant). This is an important distinction. Clinical psychologists should not usually intervene therapeutically whilst conducting qualitative research because they do not have the mandate to do so. It is therefore important to describe one’s role clearly to participants (e.g., as a clinical psychologist recruiting under that banner). This is particularly pertinent to research conducted in services where the psychologist is known and likely to encounter therapeutic expectations from participants.

Of course, some degree of therapeutic and communication skills are required by qualitative researchers. Such skills are undoubtedly helpful in managing the affect (and the risks) associated with exploring sensitive areas of a participant’s life. Indeed, all too often researchers set out with little practical training or prior experience of interviewing people. However, it is also important to be aware that these skills, which may have become second nature to many clinical psychologists, can also be misused (usually without conscious intent) to gain access to information which a participant may not wish to disclose

(Brinkmann & Kvale 2008). In short, sensitive exploration and maintaining a “therapeutic type interview alliance” may not only be facilitative of the research process but also may place implicit pressure on privacy boundaries. It is therefore important that an environment is maintained to facilitate participant autonomy in deciding whether or not to continue, so that the risks of harm caused by unwelcome intrusions into privacy are likely to be outweighed by the respondents’ ability to manage emotion.

Yanos and Ziedonis (2006) have made the useful distinction between internal and external blurring of roles. Internal role confusion, that is, where the psychologist feels the conflict between their researcher and clinician roles, is more likely to lead to situations where the research is compromised, as the needs of the participant are prioritised.

Supervision can be useful in order to identify and discuss the ethical and practical dilemmas that occur due to these blurred internal roles. External role confusion, where the research

36 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo participant confuses the role between the researcher and clinician, can be more difficult to manage as it occurs. Also, it arguably is more likely to lead to “harm” to the participant, albeit in relation to therapeutic expectation, and incursions into privacy. At the outset of research, it is imperative that the clinical psychologist describes the nature of research to potential participants and includes some discussion of different roles as well as examples of what is appropriate. Switching roles during the research process is likely to add to the role confusion experienced by participants and should only be done when careful consideration has been given to the ethical dilemmas that have occurred.

We shall now look in some detail at ethical dilemmas that fall under each of the four ethical principles described in the professional Code of Conduct of The British

Psychological Society (BPS 2006).

Four BPS Ethical Principles and Qualitative Research

The four BPS ethical principles constitute the main “domains of responsibility within which ethical issues are considered” (BPS 2006, p. 8). Each principle has an associated statement of values and a set of standards that can be used to guide ethical decision making. The principles aim to cover all actions and scenarios encountered by psychologists and are deliberately broad so as to encourage ethical decision-making to be led by the specifics of the situation. The drawback of this approach is that there is a lack of guidance for specific areas of practice, in this case qualitative research, and consequently there is a risk that some of the nuances of the ethical dilemmas may not be considered in the planning stage of research. Therefore, we discuss below the specific dilemmas in undertaking qualitative research as they relate to the existing principles, using examples from our own research.

Ethical Principle: Respect

The principle of Respect centres upon ensuring that people’s autonomy is maintained.

The BPS code specifically addresses standards concerning consideration of diversity and difference, privacy, confidentiality, informed consent and self-determination under this principle.

Diversity.

The BPS code states that psychologists should “respect individual, cultural and role differences” (p. 10), and it recognises that such differences span a large range of social identifiers (including but not exclusively concerned with age, gender, ethnicity, socio-economic status, and health). Conducting qualitative research with individuals from a different background to the researcher, for example, in relation to ethnicity, poses specific ethical and practical issues, full consideration of which is beyond the scope of this article but has also been largely ignored by existing ethical guidance (see Nazroo 2006 and Salway et al. 2009 for detailed recent discussion of the issues related to ethnicity research). This is of particular concern in clinical psychology, where the predominant position is white, middle class, young and female.

Salway et al. (2009) have recently provided a detailed set of collective social science ethics and ethnicity principles for discussion by social scientists. Many of their principles focus not only on procedure (such as ensuring that there is appropriate funding to cover the additional costs that often accompany undertaking ethnicity research) but also on consideration of the researcher’s position. For example, principle D3 reads: “Researchers should reflect critically on how their values and beliefs shape their research approach and seek to minimise ethnocentric bias in the identification of research topics and questions” (p. 74).

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research 37

For clinical psychologists conducting qualitative research there is a need to consider the biases in the theoretical models used generally, whether it be an ethnocentric bias or a focus on problematic functioning. Essentially this is an issue of reflexivity. However, it is also a point where the role of theory may contribute to ethical dilemmas; for example in implying to research participant that their experience is “abnormal.”

Much of Thompson’s research has explicitly been concerned with difference, in so far as he has explored issues of disfigurement. Conducting such research raises the question of “othering” or focusing on issues simply because there is a difference as perceived by the researcher (e.g., Shakespeare 1994). One way Thompson has sought to reflect on this is to actively seek out collaborations and guidance from charities such as Changing Faces and The Vitiligo Society and to seek peer supervision and consultation with service users, typically as part of a research steering group. This allows discussion to ensure that the research aims and focus are not just of value to the researcher.

Privacy and Confidentiality.

The code has greater detail in relation to privacy and confidentiality and includes specific guidance such as ensuring there is secure storage and consultation with colleagues prior to breeching confidence. However, the distinction between privacy and confidentiality is not clarified, and this is important when considering the implications for qualitative research. Put simply, privacy relates to areas of personal life that one is entitled to and wishes to keep private, whereas confidentiality relates to the protection of private information that one has chosen to give up for specific uses. There has been some discussion as to the issue of both privacy and confidentiality in relation to qualitative interviews (Thompson, Allmark et al. 2008; Allmark et al. 2009). A number of authors have commented on the potential for voyeurism, with others commenting on the potential for infringement into the privacy of other nonconsented individuals, as may be the case when asking about relationships, social support, or treatment (e.g., Forbat &

Henderson 2003).

Specific issues that relate to confidentiality include the difficulty in providing complete anonymity to participants who have provided detailed data. This comes from small samples, detailed biographical data and the provision of contextual background information so that even with the use of pseudonyms, readers may identify the source. This is of course an issue for all qualitative researchers but may be particularly likely when participants are recruited from professional groups, services or small participant populations (i.e., in the sorts of contexts where clinical psychologists primarily conduct qualitative research). For example, in some of the mental health research in which Thompson has been involved, small numbers of health worker participants have candidly discussed relationships with colleagues (note the link to the intrusion into others’ privacy), organisational difficulties and personal anxieties (e.g., Thompson, Powis & Carradice 2008; Donnison et al. 2009).

Some journals recognise this risk to protection of participant identity and stipulate strict guidelines to authors to ensure manuscripts not only use pseudonyms for participants’ names but also disguise recruitment sites and services (e.g., see the detailed submission guidance for Qualitative Health Research ). However, despite such precautions, some risk of identifying participants remains, and removal of too much contextual information potentially compromises the meaningfulness of the findings, creating another ethical dilemma.

One solution Thompson and colleagues have deployed is to involve participants in reviewing the excerpts which are to be reported. For example, in the Donnison et al. (2009) study, participants were sent all of the individual quotes that were proposed to be used in the thesis (this study was conducted as part of postgraduate studies) and subsequently in the journal article. The participants were asked to provide further consent for the use of the

38 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo material. This approach is distinct from member validation, which is primarily concerned with attempting to ensure credibility of the interpretations or conclusions drawn and is not suitable for all types of qualitative enquiry (Emerson & Pollner 1988). Rather the aim here is to seek further permission to use specific material. This is just one solution that also poses further dilemmas and is not necessarily suitable for all studies. Certainly, participants should be aware as to what detail will be reported and where it will be reported at the time of consent being sought.

An additional issue for those conducting research in health services is a potential for clashes between biomedical and social science perceptions of risk and confidentiality. This was highlighted during Kate Russo’s research exploring the experience of a new cross infection policy in cystic fibrosis. The NHS ethics committee considered it essential that participation in the research interviews should be noted in the medical record. Pseudonyms were used during dissemination activities, but the members of the specialist medical team could easily have identified any of the participants due to their awareness of who had participated, thus compromising confidentiality and anonymity. Further, the practice of including a note of participation in medical records relates to management of the risk associated with participation in biomedical studies where medics may need to know that a drug has been taken or a procedure has been conducted. Conversely, there is usually no need to know that someone has spoken about their experience. Thus, guidelines arising from clinical trials, where the treatment team need to know when someone is participating, may unnecessarily compromise the confidentiality of participants in qualitative research.

Other confidentiality issues specific to qualitative research include the increased likelihood of participants disclosing risk towards others. Israel (2004) discusses extreme examples of such dilemmas in conducting forensic research, and the risk to research if participants are unable to talk with immunity. However, these dilemmas are also present in other settings. For example, Russo was faced with a dilemma when her participants in the cystic fibrosis segregation study disclosed “rule-breaking” behaviour. This was particularly challenging due to the multiple roles which Russo held. During the research interviews, both young people with cystic fibrosis and their carers confided that they engaged in behaviours that were “against the rules.” For example, carers revealed the use of mobile phones in the hospital setting, which at the time was against hospital policy, and that they encouraged their child to hide their mobiles from staff. Although this caused unease about dual roles, the participants’ confidentiality was respected in this matter because there was no direct harm to others, and the information had been provided whilst Russo was in researcher role. Clearly these disclosures were useful to the findings of the research, particularly in relation to the practical recommendations that followed from the study, and could easily have been lost had participants perceived Russo to be acting entirely in her clinical role. Spending time with potential participants to clarify one’s role is important in ensuring that there is a shared understanding of the boundaries of the researcher-participant relationship.

Informed Consent and Self-determination.

The BPS code offers detailed guidance on gaining informed consent and fostering self-determination. These are related concepts and will be dealt with jointly here. Informed consent follows from an understanding of the nature, purpose and consequence of the research. Self-determination is discussed, in relation to capacity to consent and also in relation to the right to withdraw either one’s contributed data, or one’s continuing participation. Some degree of mental competence is required by participants in order to be able to engage in the decision-making necessary to give informed consent. The Mental Capacity Act (2005) has established a legal framework for people

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research 39 lacking the capacity to make decisions for themselves and the BPS provides guidance

(BPS 2008b) as to how to enhance consent and capacity to facilitate participant decision making in relation to research participation. This process is acknowledged as requiring a set of skills. The documentation is essential reading for qualitative researchers, particularly those engaging with children and vulnerable adults.

It can be difficult to guarantee privacy before an interview, simply because, in explorative qualitative research, both the participant and the researcher are unlikely to know precisely what they will end up discussing. For example, one of Thompson’s (Thompson &

Broom 2009) explorative studies involved interviews with participants living with a disfigurement, who were self-selected on the basis that they were coping well with the intrusive actions of others, and yet participants actually reported experiencing episodes of distress.

Whilst participants need to know the privacy and confidentiality “guidelines,” there will be uncertainty about what is actually going to happen. As a consequence, some have argued for an ongoing or “processual” form of consent, which facilitates participants’ option to opt out at any point (Rosenblatt 1995). However, this involves problems related to the pressures-to-continue which may be experienced by both the researcher and participant.

For the clinical psychology researcher there maybe organisational or academic demands and for the participant (particularly where there is a dual relationship) there may be a sense of duty.

For clinical psychologists who undertake research in their area of expertise, it is likely that past or current patients will fulfil the research inclusion criteria. Russo faced this dilemma during her segregation research. Excluding these potential participants would have removed the opportunity for them to have their say about their experiences, and would have effectively silenced those that were struggling with segregation, the very issue that was being researched. However, Russo was mindful of not taking advantage of the therapeutic trust that had developed in her clinical role for research gain. Russo found supervision to be essential to explore these issues, and careful exploration of roles, boundaries, and confidentiality was required to ensure informed consent.

In our experience, undertaking research in a health setting can potentially compromise voluntariness. For example, Russo was aware that in conducting interviews with young people with cystic fibrosis who were being treated in isolation, the decision as to whether to consent or not might be influenced by a drive for interaction, or even to relieve boredom.

Similarly, carers may have consented to their child being involved in the research as they were reassured that their child would not be on their own when they were unable to visit them on the ward.

Graham et al. (2006) note that whilst there is an extensive literature on experiences of participation in treatment based randomised control trials, which has explored consent in detail, there has been little study of the experience of participation in interview based studies. This was the motivation for the “Ethical Relations Study” recently reported by the

National Centre for Social Research (NatCen: Graham et al. 2007). However, the empirical research on decision-making about participation in qualitative studies is in its infancy and is somewhat equivocal. Some studies have reported participants taking a utilitarian stance derived from a sense of wanting to contribute to the area under study (Dyregrov et al. 2000;

Scott et al. 2002); others report participants simply viewing the experience neutrally (Peel et al. 2006). Conversely, some studies report participants feeling compelled by a sense of moral obligation (e.g., Ruzek & Zatzick 2000). One important finding is that many of the studies report that decision making about participation is made on the basis of the belief that it will have some function and will be disseminated (Graham et al., 2007). This is very much a belief shared by us.

40 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo

Ethical Principle: Competence

The BPS code sets out the values of competence to include reflection maintenance of high standards and covers the need for continuing professional development, supervision and the ability to address ethical dilemmas. This principle also covers the standards of recognition of the limitations of one’s own competences.

Recognition of Limitations.

Arguably clinical psychology as a profession has been somewhat slow to engage in qualitative methods (see Harper, this issue, for a discussion of qualitative methods and the profession of clinical psychology). We are trained from an empirical stance, and there is some lack of awareness of how to engage in reflexivity in research. Both of us have reflected for some time on the ethical dilemmas associated with having dual roles and have found both giving and receiving supervision to be essential in considering our limitations, an essential aspect of ethical research practice.

Ethical Principle: Responsibility

The values concerning responsibility as set out in the BPS code emphasise that psychologists should avoid harm and prevent the misuse of psychology in society.

Responsibility to Avoid Harm and Maintain Continuity of Care.

Potential harm can occur to both participant and researcher. Some of the issues have already been touched upon regarding consent and confidentiality. We will now elaborate on the dilemmas associated with harm that face clinical psychologists when conducting qualitative research. Research on participants’ experience of discussing emotive subjects is somewhat equivocal, with some studies indicating that this is distressing, and others reporting that this may be beneficial (Ruzek & Zatzick 2000; Scott et al. 2002). At a minimum, researchers should ensure that participants are debriefed at the end of the research to ensure that any emotional distress experienced during the interview has reduced, and that participants are aware of where they can access additional emotional support if needed. Graham et al. (2007) conducted

50 interviews with participants who had recently participated in NatCen (social policy) research and found that participants showed no aversion to discussing painful issues provided they felt the study was worthwhile. One implication here is that harm may be done, if participants feel that their contribution has not been useful or has not been appropriately utilised. In particular Thompson has experience of being a research participant as well as a researcher, having participated in a qualitative study that sought to explore parents’ experience of spiritual and religious needs following stillbirth and neonatal death. Having participated in this research, Thompson was keen for the findings to be disseminated.

Caution is needed in extrapolating the findings of Graham et al.’s study to qualitative clinical psychology research because the participants had participated in social policy studies, involving explorations of less personal topics, such as expectations of travel in later life.

Clearly, psychological studies may differ from policy studies in focusing upon sensitive areas of experience, may be more theoretically orientated and may use a greater amount of interpretation in the analysis. Certainly, it would be helpful to replicate this study with a sample of participants who have been involved in qualitative clinical psychology research.

Protection of Research Participants.

In section 3.3 of the BPS code the “standard of protection of research participants” is addressed, but there is no discussion of dual role despite some direct reference to overlaps between clinical and research competencies.

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research 41

For example, psychologists are advised to “inform research participants when evidence is obtained of a psychological or physical problem of which they are apparently unaware, if it appears that failure to do so may endanger their present or future well-being” and to

“arrange for assistance as needed,” yet to “exercise particular caution when responding to requests for advice” and “take particular care when discussing outcomes with research participants, as seemingly evaluative statements may carry unintended weight” (BPS 2006, p. 19).

In the following excerpt, the clash between clinician and researcher is explored in relation to a dilemma for KR in providing information whilst conducting a research interview.

The participant, a mother (M) of a girl with cystic fibrosis was explaining her views and experiences about cross infection. She was angry about the ward isolation policy. There appeared to be a misunderstanding about how bacteria were spread generally, and she was seemingly unaware of the risks of a CF person-to-person spread of bacteria which underpinned the rationale for the segregation policy. Russo, in her clinical role, felt the provision of information was needed, yet was aware that this was outside of the researcher role:

M: “

. . .

you know there’s no point, I mean (almost shouting) putting children in the room is the worst possible thing you could do for the child anyway, you know. They could be doing different things first like, um, you know, washing hands and wearing aprons and wearing gloves and that, you know, for nurses and staff. The physios do it now, but you know, the nurses don’t even do it. If the doctors are coming in, in the morning doing the ward round they do it, but nurses don’t do it. (annoyed) I’m sorry, but they just don’t do it”

KR: “You seem very concerned about the risk you see from the staff

. . .

”

M: “(interrupting) I just feel that the risk of it being passed between two [CF] children talking in the corridor is far less than someone serving dinner who’s going in and out of the bedrooms or a nurse”

KR: “Well we can talk a little bit more when the tape is off about the . . .

”

M: “(interrupting) And they are not allowed at the shop after 2, so that means if I am not in here after 2 she can’t go to the shop, she can’t get anything.

I mean, the chances of meeting someone in the shop from upstairs [a

CF child with a more severe bacteria like cepacia], is just so, it’s just so stupid”

KR: “I’m going to come back to that one when we finish to explain reasons why

. . .

”

M: “(interrupting) and there has been circumstances where (child) has asked for a nurse to go to the shop, and they don’t have time to go to the shop.

It’s not the nurse’s fault, but if this is to be done it should be done properly. You know, as a baby all the treatment she had, all the handling and all the feeding you know as a baby she was probably prone to get a lot more off the nurse, I would have thought, than another [CF] child, really.

I don’t know what the chances would be of actually passing something between a CF child and another CF child in a conversation. What are the chances, the risks?” (KR turns tape off)

As the mother appeared to be unaware that people with CF can easily spread bacteria to each other, some of the new rules of segregation seemed illogical and unfair, and resulted in her feeling angry about her daughter’s experiences in hospital. Russo reported feeling discomfort in this situation as a clinician - being aware of the nature of this person’s distress

42 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo and simply listening (rather than facilitating change with the provision of information) was difficult. Such dilemmas may occur more frequently for clinical psychologists conducting research in areas where they have expertise. To address this, Russo attempted to place boundaries upon the discussion by first suggesting returning to the topic later and then when the situation remained inflamed, terminating the research interview to switch into clinical role. Researchers may not always detect discomfort and participants can be empowered to take control of the situation themselves by making it explicit that it is perfectly acceptable for them to switch off the recording equipment.

Role blurring can also be perceived by participants. Thompson has experienced this on several occasions when, in purposively recruiting people who are likely to be experiencing distress, they have actively requested intervention. Where this happens it is important to assess the degree to which the person actually wishes to participate. This is not always clear. For example, Russo was just about to commence an interview with a mother in her cystic fibrosis study, when the participant disclosed personal difficulties adjusting to her husband’s death several years ago, and expressed concern of the impact that this was having on her child. She reported that she was glad to have contact with a clinical psychologist, as she wanted to ask advice on ways forward. Although the mother had consented to the interview, KR made the decision to not go ahead and instead gave priority to these concerns.

Ethical Principle: Integrity

The values highlighted under this principle focus on honesty, accuracy, clarity and fairness.

Section 4.2 of the code explicitly covers avoidance of exploitation and conflicts of interest, and it is here that “problems that may result from dual role or multiple relationships” (BPS

2006, p. 21) are raised. However, the subtle issues discussed in this article in relation to dilemmas arising from the interaction of researcher and clinician role are not addressed in the code.

One additional issue we have thus far not discussed is that of maintaining an open mind in seeing that conducting qualitative research in areas where we have clinical and organisational responsibilities is not skewed by political and clinical pressures. Again this calls for a high degree of reflexivity. For example, when Russo started the cystic fibrosis project, she had a view that segregation would be a negative experience and detrimental to the young patients and their families. However, recognition of this perspective allowed consideration of its influence on the emergent data which eventually led to a change in

KR’s perspective - as most people welcomed segregation despite the difficulties.

Concluding Comments and Recommendations

In this article, we have discussed some of the ethical dilemmas for clinical psychologists in conducting qualitative research, and further discussion of these issues in relation to conducting qualitative research more generally in the mental health arena can be found in Thompson and Chambers (2012). However, we recognise that many of these dilemmas will also be of relevance to others conducting qualitative research, particularly in related disciplines such as medicine, nursing and psychotherapy.

Whilst there are benefits for the qualitative researcher in also being a clinical psychologist, such as competency in empathetically addressing distress, and understanding of the clinical context, dilemmas can arise that do create uncertainty and internal conflict, as we have highlighted. Further, we have raised the need for considering one’s own positions and the influence of these on all stages of the research process.

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research

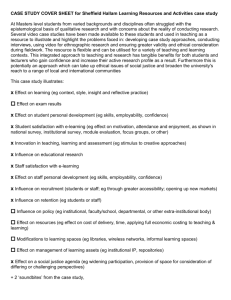

Table 1

Recommendations for facilitating ethical research practice of clinical psychologists conducting qualitative research

43

Research planning phase – and throughout the project

• Obtain appropriate supervision to ensure discussion of ethical practice, moral dilemmas and to clarify dual relationships in the context of immediate clinical roles, organisational roles, and clinical skills.

• Use a reflective diary or journal to ensure adequate consideration of ethical concerns and dilemmas, to outline decision-making processes, and to reflect upon the possible differing viewpoints from the perspective of each role held.

•

Ensure NHS ethics committees are informed of any potential challenges to confidentiality and anonymity when doing social research in a clinical setting.

Recruitment phase

• Consider factors that may influence voluntariness of participants, especially when there has been prior or current contact.

• Ensure potential participants are aware of the noninterventionist role of researcher versus the active role of the practitioner, to avoid therapeutic expectation.

•

Facilitate informed consent by providing multiple opportunities for participants to gain information about the study.

•

Check out the potential participants’ assumptions about research in advance, including perceived impact, dissemination, and use.

Data collection phase

• Facilitate understanding of confidentiality and privacy. For example, participants could be shown examples of how the information they provide will appear.

•

Ensure there is a shared understanding of the boundaries of researcher-participant relationship. For example, consider the issue of immunity and prepare for circumstances when immunity is not appropriate (i.e., when there is a risk to self or others).

•

Facilitate understanding of dual roles, if relevant. Clarify the role of the clinician versus researcher so the participant is clear. For example, explain that the research role is purely to listen to people’s experiences and not to address difficulties or explore change. If the research follows an action research model, or is linked to an intervention, explain clearly what the limits of any interventions will be, and who will be responsible for them.

•

Facilitate processual consent (the opportunity for participants to provide consent in an ongoing fashion).

• Empower the participant to have control in relation to terminating data collection without having to provide reason (this may be achieved, for example, by making it explicit that the participant can switch off recording equipment at any point without asking).

Analysis phase

•

Ensure interpretations are grounded in the participants’ accounts from the research interview and not from information obtained from other roles.

•

Consider what it will be like for participants to read or see the work in its completed form.

( Continued )

44 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo

Table 1

(Continued)

Dissemination phase

• Provide feedback and disseminate in an accessible fashion and in a way that is useful to all stakeholders (i.e., participants, staff, organisations, charitable groups, fund holders). As validation may be a motivation for participation, providing feedback could be more routinely expected, and when it is not provided, the reasons for doing so should be made explicit

•

Enhance anonymity (unless negotiated otherwise) by guarding against the use of lengthy excerpts and the use of specific personal demographic details of participants.

We have presented a number of examples from our own research practice. Others reading these anecdotes may feel that there were more appropriate ways of managing these dilemmas related to dual roles. The important issue is that these dilemmas are raised and considered. We have also discussed some of the problems associated with guidelines and the issues associated with qualitative ethicism. Consequently, in Table 1 we make a number of recommendations (most of which have been discussed above) that we hope will not only be useful to clinical psychologists but also to qualitative researchers more generally. These recommendations are derived from our experience as researchers and supervisors and our awareness of literature, and we do not assume that they are by any means definitive.

References

Allmark, P, Boote, J, Chambers, E, Clarke, A, McDonnell, A, Thompson, AR & Tod, A 2009,

‘Ethical issues in the use of in-depth interviews: literature review and discussion’, in Research

Ethics Review , vol. 5, pp. 48–54.

Brinkmann, S & Kvale, S 2005, ‘Confronting the ethics of qualitative research’, in Journal of

Constructivist Psychology , vol. 18, pp. 157–81.

Brinkmann, S & Kvale, S 2008, ‘Ethics in qualitative psychological research’, in C Willig &

W Stainton-Rogers (eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology , Sage

Publications, London.

British Psychological Society 2005, Good practice guidelines for the conduct of psychological research within the NHS , British Psychological Society, Leicester, UK.

British Psychological Society 2006, Code of ethics and conduct , British Psychological Society,

Leicester, UK.

British Psychological Society 2008a, Criteria for accreditation of postgraduate training programmes in clinical psychology , British Psychological Society, Leicester, UK.

——— 2008b, Conducting research with people not having the capacity to consent to their participation: a practical guide for researchers , British Psychological Society, Leicester, UK.

Department of Health 2001, Research governance framework for health and social care

[Browsable version], viewed 30 June 2009,

< http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/

Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4008777

>

Department of Health 2005, Research governance framework for health and social care, 2nd edn

[Browsable version], viewed 30 June 2009,

< http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/

Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_4008777

>

Department of Health: Research & Development Directorate 2007, Best research for best health: a new national health research strategy [Browsable version], viewed 30 June 2009,

< http://www.

dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/Browsable/

DH_4127225

>

Ethical Dilemmas in Conducting Qualitative Research 45

Donnison, J, Thompson, AR & Turpin, G 2009, ‘A qualitative study of the conceptual models employed by community mental health team staff’, International Journal of Mental Health

Nursing , vol. 18, pp. 310–7.

Dyregrov, K, Dyregrov, A & Raundalen, M 2000, ‘Refugee families’ experience of research participation’, Journal of Trauma and Stress , vol. 13, pp. 413–26.

Emerson, RM & Pollner, M 1988, ‘On the use of members’ responses to researchers accounts’,

Human Organization , vol. 47, pp. 189–98.

Fennig, S, Secker, A, Treves, I, Yakar, M, Farina, J, Roe, D, Levkovitz, Y & Fennig, S 2005,

‘Ethical dilemmas in psychotherapy: comparison between patients, therapists and laypersons’,

Israel Journal of Psychiatry & Related Sciences , vol. 42, pp. 251–7.

Forbat, L & Henderson, J 2003, ‘“Stuck in the middle with you”: the ethics and process of qualitative research with two people in an intimate relationship’, Qualitative Health Research , vol. 13, pp. 1453–62.

Francis, RD 2009, Ethics for psychologists , 2nd edn, BPS Blackwell, Oxford.

Graham, J, Grewal, I & Lewis, J 2007, Ethics in social research: the views of research participants ,

NatCen, London.

Graham, J, Lewis, J & Nicolaas, G 2006, A review of literature on empirical studies of ethical requirements and research participation , ESRC

/

NatCen, London.

Haggerty, KD 2004, ‘Ethics creep: governing social science research in the name of ethics’,

Qualitative Sociology , vol. 27, pp. 391–414.

Hammersley, M 1999, ‘Some reflections on the current state of qualitative research’, Research

Intelligence , vol. 70, pp. 16–18.

Harper, D 2008, ‘Clinical psychology’, in C Willig & W Stainton-Rogers (eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research in psychology , Sage Publications, London.

Holland, K 2007, ‘The epistemological bias of ethics review: constraining mental health research’,

Qualitative Inquiry , vol. 13, pp. 895–913.

Isreal, M 2004, ‘Strictly confidential? Integrity and the disclosure of criminological and socio-legal research’, British Journal of Criminology , vol. 44, pp. 715–40.

Lindsay, G & Colley, A 1995, ‘Ethical dilemmas of members of the society’, The Psychologist , vol.

8, pp. 448–51.

Martindale, SJ, Chambers, E & Thompson, AR 2009, ‘Clinical psychology service users’ experiences of confidentiality and informed consent: a qualitative analysis’, Psychology,

Psychotherapy & Research , doi: 10.1348

/

147608309X444730.

National Research Ethics Service 2001, Governance arrangements for NHS research ethics committees , NHS National Patient Safety Agency, London.

Nazroo, JY 2006, Health and social research in multiethnic societies , Routledge, London.

Peel, E, Parry, O, Douglas, M & Lawton, J 2006, ‘“It’s no skin off my nose”: why people take part in qualitative research’, Qualitative Health Research , vol. 16, pp. 1335–49.

Rosenblatt, PC 1995, ‘Ethics of qualitative interviewing with grieving families’, Death Studies , vol. 19, pp. 139–55.

Russo, K, Donnelly, M & Reid, AJ 2006, ‘Segregation – the perspectives of young patients and their parents’, Journal of Cystic Fibrosis , vol. 5, pp. 93–9.

Russo, K, Donnelly, M & Reid, AJ 2008, ‘New challenges faced by carers during their child’s hospital admission under segregation’, Journal of Cystic Fibrosis , vol. 7, Proceedings of the 31st

European Cystic Fibrosis Conference, Prague.

Russo, K & Hogg, M 2004, ‘Coping with cystic fibrosis in the family – experiences of healthy siblings’, Journal of Cystic Fibrosis , vol. 3, Proceedings of the 27th European Cystic Fibrosis

Conference, Birmingham.

Ruzek, J & Zatzick, D 2000, ‘Ethical considerations in research participation among acutely injured trauma survivors: an empirical investigation’, General Hospital Psychiatry , vol. 22, pp. 27–36.

Salway, S, Allmark, P, Barley, R, Higgenbottom, G, Gerrish, K & Ellison, TH 2009, ‘Social research for a multiethnic population: do the research ethics and standards guidelines of UK learned societies address this challenge?’, 21st Century Society , vol. 4, pp. 53–81.

46 A. R. Thompson and K. Russo

Scott, D, Valery, P, Boyle, F & Bain, C 2002, ‘Does research into sensitive areas do harm?

Experiences of research participation after a child’s diagnosis with Ewing’s sarcoma’, Medical

Journal of Australia , vol. 177, pp. 507–10.

Seider, S, Davis, K & Gardner, H 2007, ‘Good work in psychology’, The Psychologist , vol. 20, pp.

672–6.

Shakespeare, T 1994, ‘Cultural representations of disabled people: dustbins for disavowal’, Disability and Society , vol. 9, pp. 283–99.

Small, R 2001, ‘Codes are not enough: what philosophy can contribute to the ethics of educational research’, Journal of Philosophy of Education , vol. 35, pp. 387–406.

Thompson, AR, Allmark, P, Todd, A, McDonnell, A & Clarke, A 2008, ‘Ethical dilemmas in conducting, analysing and reporting on qualitative interviews’, Invited oral presentation at the British

Psychological Society Annual Conference, Dublin.

Thompson, AR & Broom, L 2009, ‘Positively managing intrusive reactions to disfigurement: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of naturalistic coping’, Diversity in Health Care , vol. 6, pp. 171–80.

Thompson, AR & Chambers, E 2012, ‘Ethical issues in qualitative mental health research’, in D Harper & AR Thompson (eds.), Qualitative research methods in mental health and psychotherapy: a guide for students and practitioners, pp. 23–38, Wiley, London.

Thompson, AR, Donnison, J, Warnock-Parkes, E, Turpin, G, Turner, J & Kerr, I 2008, ‘An evaluation of the impact of a six month ‘skills level’ training course in cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) with multidisciplinary community mental health team (CMHT) staff’, International Journal of Mental

Health Nursing , vol. 17, pp. 129–35.

Thompson, AR, Kent, G & Smith, JA 2002, ‘Living with vitiligo: dealing with difference’, British

Journal of Health Psychology , vol. 7, pp. 213–25.

Thompson, AR, Powis, J & Carradice, A 2008, ‘Community mental health nurses’ experiences of working with people who engage in deliberate self-harm: an interpretative phenomenological analysis’, International Journal of Mental Health Nursing , vol. 17, pp. 151–9.

Yanos, PT & Ziedonis, DM 2006, ‘The patient-oriented clinician-researcher: advantages and challenges of being a double agent‘, Psychiatric Services , vol. 57, pp. 249–53.

About the Authors

Andrew R. Thompson is a Reader in Clinical Psychology and a Registered

/

Chartered

Clinical Psychologist and Health Psychologist. He is Director of Research Training on the

Clinical Psychology Training Programme, University of Sheffield, UK. He has an interest in the use of qualitative methods in clinical psychology research and a substantive research interest in adjustment to chronic illnesses and conditions affecting appearance.

Kate Russo , a Chartered Clinical Psychologist, is a Paediatric Clinical Psychologist at the

Royal Belfast Hospital for Sick Children and specialises in cystic fibrosis. She is also

Assistant Course Director for the DClinPsych program at Queens University Belfast. She has an interest in the use of qualitative methods to improve service delivery in health settings.