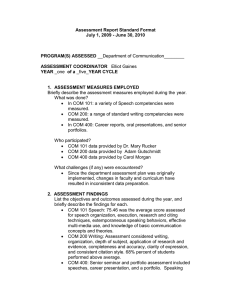

Portfolio Assessment A. The Nature of Portfolio Assessment The concept of portfolio assessment is not new. Portfolios originated with artists’ collections of their works and have long been used to demonstrate competencies. In response to the need for alternative and more authentic assessment practices, portfolios have become a common alternative to the traditional assessment methods (Mayers and Tusin, 1999). Portfolios assessment is a term with many meanings, and it is a process that can serve a variety of purposes. A portfolio is a collection of student work that can exhibit a student’s efforts, progress and achievement in various areas of the curriculum. A portfolios assessment can be an examination of student-selected samples of work experiences and documents related to outcomes being assessed and it can address and support progress toward achieving academic goals, including student efficacy. Portfolio assessments have been used for large-scale assessment and accountability purposes (e.g., the Vermont ad Kentucky statewide assessment system), for purposes of school-to-work transitions, and for purposes of certification. For example, portfolio assessments are used as part of the National Boards for Professional Teaching Standards assessment of expert teachers. Moreover, based on the constructivist theories, which advocate that learning has to be constructed by the learners themselves, rather that being impacted by the teachers, portfolio assessment requires student to provide selected evidence to show that learning relevant to the course objectives has taken place. They also have to justify the selected portfolio items with reference to the course objectives (Steffe and Gale, 1995). Biggs (1996) holds that the preparation of an assessment portfolio s an active process involving collecting, synthesizing and organizing possible relevant items to provide the best evidence of achievement of the learning objectives; a process that demands ongoing assessment, reflection and justification. There is also the assumption that during the process of preparing an assessment portfolio, learning is enhanced as students are encouraged to reflect on their experience, identify learning needs and initiate further learning (Harris, Dolan & Fairbairn, 2001). Such an assumption, however, should be supported with empirical evidence if the full potential of portfolio assessment s to be realized Genesse and Upshur (1996) define portfolio as follows: A portfolio is purposeful collection of students’ works that demonstrates to the students and others their efforts, progress and achievements in given areas. Students should have their own portfolios, which can be a conventional file folder, a small cardboard box, a section of a file drawer ow some other such receptacle (p.99). they maintain that the value of portfolios is in the assessment of student’s achievement. They are particularly useful in this respect because they provide a continuous record of students’ development that can be shared with others. Genesee and Upshur clearly state that reviewing portfolio can increase the students’ involvement in and ownership of their own learning. The positive effects of portfolios on student learning arise from the opportunities they afford students to become actively involved in assessment and learning. B. Theoretical Background of Portfolio Assessment The underlying philosophy of this alternative approach to evaluation is that student is encourage to become more autonomous and to take more responsibility for their work, including the evaluation of it. Belanoff (1944) believes that portfolio assessment promotes participation and autonomy by allowing students to select the work on which they will be evaluated to reflect on tier work to take control of revision and have the opportunity to produce substantive revision to be granted the time to grow as writers; to take risks with their writing and to seek advice from peers. The result is that evaluation becomes a positive force to encourage growth, maturity and independence rather than a means of pointing out deficiencies. C. Stages in Implementing Portfolio Assessment It is very essential discussing the stages in implementing the portfolios assessment. Because portfolio takes a very long time and needs much energy, the teacher should e focused and careful in implementing and assessing it. Therefore, it will be helpful by following these stages for saving the time and energy. 1. The first stage is identifying teaching goals to assess through portfolio. It is very important at this stage to be very clear about what the teacher hopes to achieve in teaching. These goals will guide the selection and assessment of students’ work for the portfolio. 2. The second stage is introducing the idea of portfolio. Portfolio assessment is a new thing for many students who are used to traditional setting. For this reason, it is important for the teacher to introduce the concept to the class. 3. The third stage is specification of portfolio content. Specify what and how much have to be included in portfolio – both core and options (it is important to include options as these enable self-expression and independence). Specify for each entry how it will be assessed. 4. The fourth stage is giving clear and detailed guidelines for portfolio presentation. There is tendency for students to present as many evidences of learning as they can when left on their own. The teacher must therefore set clear guidelines and detailed information on how the portfolios will be presented. 5. The fifth stage is informing key school officials, parents, and other stakeholders. Do not attempt to use the portfolio assessment method without notifying your department head, dean or principals. This will serve as a precaution in case students will later complain about your new assessment procedure. 6. The sixth stage is development of the portfolio. Support and encouragement are required by both teacher and students at this stage. Devote class-time to studentteacher conferences, to practicing reflection and self-assessment and to portfolio preparation. Then ensuring that the portfolio represents the students’ own works and giving guiding feedback to them. D. Types of Portfolios While portfolios have broad potential and can be useful for the assessments of students; performance for a variety of purposes core curriculum areas, the contents and criteria used to assess portfolios must be signed to serve those purposes. For example, showcase portfolios exhibit the best of student performance, while documentation portfolios may contain draft that students and teacher use to reflect on process. Progress portfolios contain multiple examples of the same type of work done over time and are used to assess progress. If cognitive processes are intended for assessment content and rubrics must be deigned to capture those processes. Portfolio assessments can provide both formative and summative opportunities for monitoring progress toward reaching identified outcomes. By setting criteria for content and outcomes, portfolios can communicate concrete information about what is expected of students in terms of the content and quality of performance in specific curriculum areas, while also providing a way of assessing their progress along the way. Depending on content and criteria, portfolios can provide teachers ad researchers with information relevant to the cognitive prosses that students use to achieve academic outcomes. E. Purposes of Portfolios Much of the literature on portfolio assessment has focused on portfolios as a way to integrate assessment and instruction and to promote meaningful classroom learning. Many advocates of his function believe that a successful portfolio assessment program requires the ongoing involvement of students in the creation and assessment process. Portfolio design should provide students with the opportunities to become more reflective about their own work, while demonstrating their abilities to learn and achieve in academics. For example, some feel it is important for teachers and students to work together to prioritize the criteria that will be used as a basis for assessing and evaluating student progress. During the instructional process students and teachers work together to identify significant pieces of work and the processes required for the portfolio. As students develop their portfolio, they are able to receive feedback from peers and teachers about their work. Because of the greater amount of time required for portfolio projects, there is a greater opportunity for introspection and collaborative reflection. This allows students to reflect and report about their own thinking processes as they monitor their own comprehension and observe their emerging understanding of subjects and skill. The portfolio process is dynamic and is affected by the interaction between students and teachers. Portfolio assessments can also serve summative assessment purposes in the classroom, serving as the basis for letter grades. Students conferences at key points during the year can also be part of the summative process. Such conferences involve the students and teacher (ad perhaps the parent) in joint review of the completion of the portfolio components, in querying the cognitive processes related to artifact selection, and in dealing with other relevant issues, such as students’ perceptions of individual progress in reaching academic outcomes. The use of portfolios for large-scale assessment and accountability purposes pose vexing measurement challenges. Portfolios typically require complex production and writing, task that can be costly to score and for which reliability problems have occurred. Generalizability and comparability can also be an issue in portfolio assessment, as portfolio tasks are unique and can vary in topic and difficulty from one classroom to the next. For example, Maryl Gearhart and Joan Herman (1995) have raised the question of comparability of scores because of differences in the help students may receive from their teachers, parents and peers within and across classrooms. To the extent student’s choice is involve, contents may even be different from one student to the next. Conditions of and opportunities for, performance thus vary from one student to another. These measurement issues take portfolio assessment outside of the domain of conventional psychometrics. The qualities of the most useful portfolios for instructional purposes-deeply embedded in instruction, involving students’ choices, and unique to each classroom and student-seem to contradict the requirements of sound psychometrics. However, this does not mean that psychometric methodology should be ignored, but rather that new ways should be created to further develop measurement theory to address reliability, validity and generalizability. F. Pros and Cons of Portfolio Assessment Pros: 1. Provides tangible evidence of the student's knowledge, abilities, and growth in meeting selected objectives which can be shared with parents, administration and others 2. Involves a considerable amount of student choice - student-centered 3. Involves an audience 4. Includes a student's explanation for the selection of products 5. Places responsibility on the students by involving them in monitoring and judging their own work 6. Encourages a link between instructional goals, objectives, and class activities 7. Offers a holistic view of student learning 8. Provides a means for managing and evaluating multiple assessment for each student. The portfolio provides the necessary mechanism for housing all the information available about a student’s learning. It includes a variety of entries including test scores, projects, audio tapes, video tapes, essays, rubrics, self-assessments, etc. 9. Allows students the opportunity to communicate, present, and discuss their work with teachers and parents. Cons: 1. Takes time 2. Present challenges for organization and management (Portfolio Assessment, 1999) G. Self-Assessment and Peer Assessment Portfolio assessment is the only methodology that responds directly to the goal of training students to assess their own success. It incorporates collecting and reviewing artifacts, understanding progress through record keeping, documenting interests and preferences, conferencing with teacher and peers. It also combines instruction with assessment that allows for self-reflection and self-evaluation. Students can become better learner when they engage in deliberate thought about what they are learning and how they engage in deliberate thought about what they are learning and how they are learning it, in this kind of reflection students step back from the learning process to think about their learning strategies and their progress as learners. Such self-assessment encourages students to become independent learners and can increase their motivation (McMullan, 2006). Moreover, Crooks (2001) also maintain that self-assessment provides students with the opportunity to understand the grading system. They can eliminate the controversy regarding subjective grading and gain ownership in their learning process. When students are involved with self-assessment, they are better able to work with other students, exchange ideas, get assistance when needed, and be more involved in cooperative and collaborative learning activities. As these students go about learning, they begin to construct meaning revise their understanding, and share meanings with others, the benefits of incorporation peer assessment into the regular assessment procedures have been discussed in a number of studies. Peer assessment is believed to enable learners to develop abilities and skills denied to them in a learning environment in which the teacher alone assesses their work. In other words, it provides learners with the opportunity to take responsibility for analyzing, monitoring, and evaluating aspects of both the learning process and product of their peers. Research studies examining this mode of assessment have revealed that it can work towards developing students’ higher order reasoning and higher-level cognitive thought, helping to nurture student-centered earning among undergraduate learners, encouraging active and flexible learning and facilitating a deep approach to learning rather than a surface approach (Gibbs, 1992). Peer assessment can act as a socializing force and enhances relevant skills and interpersonal relationships between learner groups, in addition Gallagher (2001) also maintains that reflection is a major component of portfolios as it helps students to learn from experience and practice, thereby helping them to bridge the theory-practice gap. He says through the reflective process students are able to identify gaps in knowledge and/or skills and competence, but also to reconfirm and document strength, skills and knowledge. H. Sample of Students Portfolios 1. Example of Portfolios for Different Subjects a. English/Language Arts: i. Reading log ii. Different types of writing 1. Poems 2. Essay 3. Letters iii. Test iv. Book summaries/reports v. Dramatizations vi. Student reflections b. Science: i. Charts, graphs created ii. Project, posters iii. Lab reports iv. Research reports v. Test vi. Students reflections 2. Rubrics Points 90-100 Required Items Concepts Reflection/Critique Overall Presentation All required items are Items clearly Reflection illustrate the Items are clearly included, with a demonstrate that the ability to effectively introduced, well significant number of desired learning critique work and to organized, and additions. outcomes for the term suggest constructive creatively displayed, have been achieved. The practical alternative. showing connection student has gained a between items significant understanding of the concepts and applications. 75-89 All required items are Items clearly Reflections illustrate Items are introduced and included, with a few demonstrate most of the the ability to critique well organized, showing additions. desired learning work, and to suggest connection between outcomes for the term. constructive practical items. The student has gained a alternatives. general understanding of the concepts and applications. 60-75 All items required are Items demonstrate some Reflections illustrate an Items are introduced and include. of the desired learning attempt to critique somewhat organized, outcomes for the term. work and to suggest showing some The student has gained alternatives connection between some understanding of items. the concepts and attempts to apply them. 40-59 A significant number of Item do not demonstrate Reflections illustrate a Items are not introduced required items are basic learning outcomes minimal ability to and lack of organization. missing. for the term. The student critique work has limited understanding of the concepts 0 No work submitted References Belaoff, P., & Dickson, M. (1991). Portfolios: Process and Product. Biggs, J. B. (1996). The Teaching Context: The Assessment Portfolio as a Tool for Learning. Crooks, T. (2001). The Validity of Formative Assessment. University of Leeds. Gallagher, P. (2001). An Evaluation of Standard-Based Portfolio. Nurse Education Today, 409-416. Gearhart, M., & Herman, J. L. (1995). Portfolio Assessment: Whose Work Is It? Issues in the Use of Classroom Assignments for Accountability. Evaluation Comment. Genesee, F., & Upshur, J. (1996). Classroom-based Evaluation in Second Language Education. Cambridge University Press. Gibbs, G. (1992). Down with Essay. The New Academic, 18-19. Harris, S., Dolan, G., & Fairbarn, G. (2001). Reflecting on the Use of Student Portfolios. Nurse Education Today, 278-286. Mayer, D. K., & Tusin, L. F. (1999). Pre-service Teachers' Perception of Porfolios: Process versus Product. Journal of Teacher Education, 131-139. McMullan, M. (2006). Students' Perception on the Use of Portfolios in Pre-registration Nursing Education: A Questionnaire Survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 333-343. Portfolio Assessment. (1999). Assessment, Articulation and Accountability, 178-208. Steffe, L., & Gale, J. (1995). Constructivism in Education. Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ.