Essay

Effect of Minimum Wage on Employment

Bachir P. El-Rassi

Royal Military College

Abstract

This essay briefly reports on findings of research done on the effects of minimum wage on various

measures like employment (dis-employment), CPI, GDP and the age group of workers, industries

and skill level of workers most affected. Most research have contrasting results where some claim

that raising the minimum wage will have immediate negative effect on the employment of teens

and recent immigrants specifically the unskilled ones. Others like Card and Kreuger (1992 and

2000) showed that a raise in the minimum wage can have a positive impact on employment which

was supported by a later study but isolated to small restaurants and not fast-food chains.

2

1.

Introduction

A minimum wage is the lowest wage that employers may legally pay to workers. Minimum

wage has those who advocate for it and others who oppose it. The most obvious advocates are the

direct beneficiaries, the employees, at least the ones that do not lose their job as a consequence of

implementing or raising the minimum wage. The argument is that the raising of the minimum

wage will increase earnings, increase total demand for goods and services, reduce inequality and

reduce employee turnover (Bradley, p. 6). The opposition are the businesses that will now have

higher costs and lower profit margins or maybe even go bankrupt. The argument is that the raising

of the minimum wage will not reduce poverty, will reduce employment, will increase prices and

reduce profits. The government can be either an advocate or an opponent depending on whether it

raises the overall tax collection and / or it is used as a political move to appease the masses and

roll in more votes.

The rest of the paper is divided into sections. The second section will provide a brief general history

of the minimum wage followed by the history in the United States (US) and in Canada since these

two countries share many economic similarities, living standards and policies. The third section

contains a summary of recent literature from Canada, US and international academics that

evaluated the effects of minimum wage on employment. Two Canadian articles will be discussed

in more detail than others due to the fact that they do a comprehensive research on the effect of

minimum wage on employment in Canada. These are by “Rybczynski and Sen” and Shumakova.

The last section is the conclusion.

3

2.

History

2.1.

General

Wikipedia.org1 traces the history of the modern minimum wage laws to the Ordinance of

Labourers in 1349. After the black plague killed many people in 1348, labour shortage caused

wages to soar and the ordinance by King Edward III set a wage ceiling. In 1389, it was amended

to set wages to the price of food and kept on evolving until eventually King James I passed an act

to set a formal minimum wage for workers in the textile industry in 1604. As of 2013, the hourly

minimum wages in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)

developed countries range from $0.62 in Mexico, up to $15.61 in Australia. Canada’s was $9.85

which is just above the UK, Japan and US and just below some European countries. An interesting

and valuable ratio to consider is the minimum wage divided by the average wage for the same

OECD countries. Canada’s ratio is in the middle at 0.39 with Mexico and the US taking the lowest

spot at 0.27 and New Zealand leading with a ratio of 0.51.

2.2.

United States

Wikipedia2 says that New Zealand was the first country to enact a national minimum wage

in 1894 by the Industrial Coalition and Arbitration Act that established arbitration boards to

enforce compulsory arbitration. The Center for Poverty Research at the University of California

published on their website3 this brief history of the minimum wage in the US. In 1938, The Fair

Labor Standards Act (FLSA) was enacted nationally and it set the minimum wage initially at $0.25

per hour for covered workers. The FSLA provided a number of federal protections for the first

1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minimum_wage#Debate_over_consequences

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_minimum_wage

3

https://poverty.ucdavis.edu/faq/what-history-minimum-wage

2

4

time including: payment of the minimum wage, overtime pay for time worked over a set number

of hours in a work week, restrictions on the employment of children and recordkeeping

requirements. Interestingly, the Wikipedia site referenced earlier, mentions that the state of

Massachusetts set minimum wages for women and children in 1912 (26 years before the FSLA)

and other states followed suit.

As of July 2009, two years after the last amendment was enacted, the minimum wage is at

$7.25 after being raised 22 separate times. States can and do set their own minimum wage but

workers will get paid the minimum wage that is the higher of the FSLA or the minimum wage set

by the state (Bradley, p. 6). The National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) published the

following statistics about the minimum wage in each state on its website4. Eighteen states began

the 2018 New Year by increasing their minimum wages to automatically match the cost of living

(CPI) while eleven others increased their rate due to scheduled legislation. Currently, five states

have no minimum wage law, two have wage lower than the FSLA, 14 states match the FSLA and

29 states have minimum wage that is higher than the FSLA with the highest in D.C. at $13.25.

The FSLA does not cover the following workers: workers with disabilities, certain youth

workers, bona fide executives/administrative/professional employees, seasonal workers, state or

local government workers, farmers, small circulation newspapers, casual domestic service

workers, newspapers delivery workers, and certain employees in computer related occupations.

The FSLA allows payment of wages below the minimum wage to the following groups: youth,

learners, full time students, individuals with disabilities and tipped workers. In 1938, the FSLA

4

http://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/state-minimum-wage-chart.aspx

5

represented about 20 percent of the labor force but coverage has been expanded over time and now

covers approximately 130 million workers or 84 percent of the labor force (Bradley).

2.3.

Canada

The initial attempt was through the federal “Fair Wages Policy” in the 1900, which was

modified to become more comprehensive in the 1920 and by that time six provinces have passed

similar laws. Economists have for many years disagreed about their effectiveness, arguing that

they may price low-skilled workers out of the market and cause unemployment. The Canadian

minimum wage legislation was initially intended to prevent the exploitation of workers by firms

after which it was amended to ensure workers received a subsistence wage and eventually evolved

to protect the vulnerable groups (women, young workers and new immigrants) from

discrimination. By the mid-1950s, most Canadian provinces had enacted minimum wage

legislation for male employees. In 1996, the federal minimum wage was eliminated and the

provincial minimum wage was used for the federal employees in those specific provinces. The

Canada Labour Code applies to organizations under federal jurisdiction and it regulated minimum

wage, overtime pay, equal pay, child labour and record keeping (Schwind et al). Comparable to

the US minimum wage laws, the law covered some jobs but not executive, administrative,

professional and other employees. The Canada Labour Code was repealed and replaced by the

Canadian Human Rights Act in 1977.

The federal hourly minimum wage in Canada as reported by the Government of Canada5

was $1.65 in 1965 and steadily increased to $7.5 in 1996. The provinces set their own minimum

5

http://srv116.services.gc.ca/dimt-wid/sm-mw/rpt2.aspx

6

wage and as of 2018 it is: Alberta ($15.00), British Columbia ($12.65), Manitoba ($11.35), New

Brunswick ($11.25), Newfoundland and Labrador ($11.15), Northwest Territories ($13.46), Nova

Scotia ($11.00), Nunavut ($13.00), Ontario ($14.00), Prince Edward Island ($11.55), Quebec

($12.00), Saskatchewan ($11.06) and Yukon ($11.51).

Statistics Canada6 published the minimum wage from 1975 to 2014. Taking inflation into

account, the highest real minimum wage was in 1976 at $11 an hour where the average hourly

peaked at $24. Over the same time period, the average minimum wage is $10.39 per hour and the

average hourly wage is between $22.70 and $24.51 per hour depending on the data source. The

ratio of the real minimum wage to the average hourly earnings is always just under 0.5. The

proportion of employees paid at the minimum is lowest in Alberta and highest in Ontario while

the proportion for Canada is just over 7%. The proportion of the groups most likely to get paid

minimum wage did not change much from 1997 to 2014. These groups are youth (15-19 at 49%,

20-24 at 15%), women (9% compared to 6% for men), students (29%) and people with lower level

of education (20% compared with 3% of people with university degree).

3.

Literature Review

3.1.

United States

Bradley published the CRS Report “The Federal Minimum Wage: In Brief” in June 2017

and it was prepared for the members and committees of Congress. The report state that there are

approximately 2.2 million workers (2.7 %) with wages at or below the minimum wage and most

are female, above 20 years of age and work part time in the food industry. The report identified

6

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-630-x/11-630-x2015006-eng.htm

7

the characteristics of minimum wage workers by age, gender, work status (full or part time),

occupation and educational attainment. The age percentages are: 16-19 at 20.6 %, 20-24 at 24.8

%, 25-29 at 13.8 % and above 30 at 40.9 %. The gender percentages are: men at 35.7 % and women

at 64.3 %. The work status percentages are: full-time at 41.1 % and part-time at 58.9 %. The

occupation percentages are: service (healthcare, protective, food, building and ground

maintenance, personal care) at 66.5%, sales and office at 16.8 % and all other at 16.7 %. The

educational attainment percentages are: less than high school at 21.3 %, high school at 31.0 %,

some college at 27,.5 %, associate’s degree at 8.9 % and Bachelor’s and higher at 11.4 %.

Elwell summarized the real minimum wage in his report to the members and committees

of Congress. Because of inflation and the fact that the minimum wage is not indexed to the price

level, the real purchasing power is lost. Elwell calculated real minimum wages for every year there

was a minimum wage amendment and used 2013 dollars based on the CPI index (100 in 1984).

The year with the highest real minimum wage, $10.69, was 1968 which had a minimum wage of

$1.6 and a CPI of 34.3. The current minimum wage is $ 7.25 and in order to now have the same

purchasing power as in 1968, the minimum wage has to increase by $3.44 (47%) to $10.69.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) authorized a study in 2014 to determine “The

Effects of Minimum-Wage Increase on Employment and Family Income” (Elmendof, D., 2014).

The CBO’s mandate is to provide objective and impartial analysis so the report does not make any

recommendations. The overall result is that most low wage workers would have a higher family

income and some would rise above the poverty threshold; however, some other jobs for low wage

8

workers would probably be eliminated. The study considered two options to raise the minimum

wage to either $10.10 or $9.00.

The $10.10 option would see a loss of about 500,000 jobs (0.3 %) but could be larger up

to 1 million. About 16.5 million would have higher earnings and 900,000 would be moved above

the poverty line. There will be change to real income of about $5 billion (bn), $12 bn, $2 bn and

-$17 bn for families with income below, between 1 and 3 times, between 4 and 6 times and above

6 times the poverty threshold respectively. The net change is a $2 bn increase in family income.

The $9.00 option would see a loss of about 100,000 jobs (0.1 %) but could be larger up to

200,000. About 7.6 million would have higher earnings and 300,000 would be moved above the

poverty line. There will be change to real income of about $1 billion (bn), $3 bn, $1 bn and -$4 bn

for families with income below, between 1 and 3 times, between 4 and 6 times and above 6 times

the poverty threshold respectively. The net change is a $1 bn increase in family income.

3.2.

Canada

Brecher and Gross used a simple general-equilibrium model of perfect competition to show

that higher minimum wages may paradoxically lead to greater levels of total employment if the

income redistribution effect outweighs the substitution effects in production and consumption.

They argue that this outcome is possible because of a difference in the factor intensity between

industries and a taste difference between consumers as well as hiking the minimum wage

redistributes income between heterogeneous consumers. Simply put – since low income wage

9

earners spend almost all of their income in the economy, this money goes back into the economy

which leads to an increased demand for labour, which leads to more wages being earned.

Brouillette et al found that the consumer price index (CPI) inflation could be boosted by

about 0.1 % on average in 2018 and reduce the gross domestic product (GDP) by roughly 0.1 %

by early 2019 as a consequence of raising the minimum wage. As well, although the net impact on

labor income would be positive, employment would fall by 60,000 which is a number that lies in

the lower part of a range (30,000 - 140,000) obtained from an accounting exercise. Higher inflation

would cause an increase in interest rate which forces consumption to decline and that would more

than offset the higher labour income. A change of 0.1% in an index that varies between 1.5 and

2% will not cause an increase in interest rates as there are many other factors, including politics

that shape interest rate policies for national institutions such as the US Federal Reserve and the

Bank of Canada.

Galarneau and Fecteau’s study in 2014 state that teens account for half of all minimum

wage workers and that one in three teens work for the minimum wage. As well, the study found

that prime-aged (25-54) women, immigrants, and low educated workers constitute a

disproportionate percentage of minimum wage earners. The study looked at industries with

significant numbers of minimum wage employees between 1975 and 2013, and found that the

average hourly earnings are stable and range from $18 to $24 using 2013 dollars. The minimum

wage has steadily increased specifically over the last ten years and hence the ratio of the real

minimum wage to the real average hourly earnings steadily increased from around 40% in 2005 to

45% in 2013 mainly driven by minimum wage amendments.

10

Lau wrote the paper “Against the Minimum Wage” and was published by the “Frontier

Centre for Public Policy”. Lau claims that based on the best empirical research and basic economic

theory, the three consequences of raising the minimum wage are: an increase in poverty (or in the

best case no discernible effect on poverty), a decrease in employment especially among young

workers and finally reduced economic growth. Lau mentions a study by a government of Ontario

think tank that supports the first two consequences: poverty and unemployment. Lau quotes Nobel

Laureate Milton Freidman and what he said about minimum wage legislation: “about as clear a

case as one could hope to find of a measure whose effects are precisely the opposite of those

intended by the men of goodwill who support it”. Others are also impacted and those are the

businesses that have to close because they can’t absorb the higher labor costs and the consumers

who now have lost shopping option because of the closure. Lau recommends an immediate freeze

on minimum wages and ideally should be scrapped completely.

Riddell states in his paper, “The Labor Market in Canada, 2000 – 2016”, that Canada is

situated about halfway between the US and Europe when considering the extent of unionization

and the level of the minimum wage relative to the median wage. Riddell credits the resource boom

from the 1990s to 2014 as the reason behind Canada’s economy and labor market performing well.

During the researched period, 2000-2016, the economic downturns were much less pronounced

than earlier periods and milder than in the US and much of Europe. As well, real wage gains were

substantial, income equality has been stable and the male – female earnings gap has continued to

decline. There has been substantial labor reallocation due to job losses and unemployment in

resource rich regions since 2014. The substantial gains in real wages have been unevenly shared

with the lion’s share going to the top of the income distribution.

11

Rybczynski and Sen researched in 2017 the effects of the minimum wage by using panel

data from Canadian provinces as evidence. Although recent US studies offer conflicting evidence

on minimum wage impacts, the authors estimate a 10% increase in minimum wage is associated

with 1%-4% reduction in employment rates of both male and female teens and prime-aged

immigrants. The study used data from all Canadian provinces from 1981 to 2011 to research the

effects of 185 amendments to minimum wage on employment rates. The study makes use of crossprovince data and time-series variation with a large number of legislated amendments. The authors

estimated minimum wage effects across age groups, gender and with respect to immigrants. They

state that the Canadian data are appropriate to study the effects on immigrants because the

percentage of recent immigrants (less than 10 years) earning minimum wage has risen sharply

(6.9% in 1998 to 19.1% in 2011) since the late 1990s.

The results from Rybczynski and Sen’s paper were divided into four areas. The first area

contains the baseline estimates for teens and prime-aged adults using data from 1981-2011. The

second area contains the estimates for teens (15-19), older teens (18-19) and for immigrants (other

vulnerable groups) using data from 1990-2011. The third area contains the results of sensitivity

checks and finally the fourth area contains the results of Instrumental Variables (IV).

For the first area that contains the baseline estimates for teens and prime-aged adults using

data from 1981-2011, there was no statistically significant gender difference in the drop of teen

employment; however, the 10% increase in the minimum wage was found to be significantly

correlated with a 1%-4% reduction in employment rates for both genders. Put another way, the

coefficient estimates of the effects of the minimum wage on employment rates were negative and

12

statistically significant at either the 1% or 5% levels. The study conducted a robustness check by

employing province and year effects, province specific linear trends and quadratic trends and the

authors arrived at the same results stated earlier. There was small and statistically insignificant

effect of minimum wage on employment of prime-aged adult men and women. Additionally, there

was no evidence of disproportionate employment effects on women although women are more

likely to earn minimum wage than men.

The second area contains the results for teens, older teens and immigrant’s data from 19902011. Older teens will receive at least the adult minimum wage whether they have finished high

school or not. School enrollment will tend to be higher in a high unemployment economy in an

effort of workers to improve or acquire new skills. The authors calculated the coefficient estimates

at the baseline and a second set using the baseline plus the enrollment numbers. They used school

enrolment rate since enrolled students are very likely to work part time jobs which pay at or near

the minimum wage. Area one used data from 1981-2011 and area two used data from 1990-2011.

The results for teens using the data from 1990-2011 were larger (in the negative) and still

statistically significant at the 1% than those teens using data from 1981-2011. This indicates that

more teens are earning minimum wage post 1990. The results for older teens are similar to teens

and are larger for women than for men; however, they are less precise than those for teens. The

authors state that immigrants are overlooked and are becoming an increasingly relevant population

group. For young immigrants aged 16-24, the coefficient estimates are negative but statistically

insignificant. For prime-aged immigrants aged 25-54, the coefficient estimates are negative and

statistically significant except when using a quadratic in provincial linear trend. When using a

quadratic in provincial linear trend, the coefficient estimates are negative but statistically

13

insignificant which is expected given the small sample size of immigrants relative to the whole

population. The findings in this area for the prime-aged immigrants contrasts with the findings in

area one for prime-aged adults for the Canadian population as a whole.

In the third area, the authors performed sensitivity checks on teen employment rates only

since the sample data pool is large and the findings are robust (statistically significant at 1%).

To confirm their findings, the authors used leaded and lagged values of the minimum wage. That

is, they used values of the minimum wage from each of the 3 years following and the 3 years

lagging to determine if there is a statistically significant relationship between these values and the

current employment rate. After the inclusion of the leaded values, the coefficient estimates

remained statistically significant. Since it may take at least one year for the full effects of any

minimum wage amendment to manifest, the authors used the lagged values of employment rates

as well. The coefficient estimates of the effects of the minimum wage on lagged employment rates

were substantial, negative and statistically significant. Additionally, the authors used two other

methods to perform a sensitivity check. First, they researched the effect of the size of the change

of the minimum wage on employment rate and found that there is no differential impact on

employment outcomes if the minimum wage increase exceeds 5%. Given that two-thirds of

minimum-wage hikes are within 2.5% of the 5% level, the preceding result was not a surprise.

Second, the authors excluded the recessionary periods and concluded that the coefficient estimate

of the effect of the minimum wage on employment rate is negative, larger in magnitude and more

precise.

14

The fourth area of the study contains the results of introducing Instrumental Variables (IV)

to determine the robustness of the earlier findings and deal with the possible simultaneity bias. The

authors state the following about the simultaneity bias:

“If increases in the minimum wage are a policy response to increases in low-wage

unemployment, then least squares estimation will result in coefficient estimates that are biased

and inconsistent. Thus, IV estimation can be a possible strategy to address the concerns.”

The following IVs where introduced: regional average log real minimum wage,

Progressive Conservative Party (PC), Liberal Party (Lib), New Democratic Party (NDP) and three

additional instruments that are the proportion of seats held by the PC, Lib and NDP in each

province and in each year. The authors find that, using the IVs, the coefficient estimates of the

effects of the minimum wage on employment rate are negative, large and statistically significant.

The authors, Rybczynski and Sen, conclude that their results are robust and that an increase

in minimum wage is significantly correlated with unemployment for teens and that they did not

find significant gender differences in minimum wage effects. As well, they found that the effect

on prime-aged immigrants is as large as it is on teens.

Shumakova wrote the paper “The Effect of the Minimum Wage on the Employment Rate

in Canada, 1979 – 2016” as a requirement for an M.A. degree at the Department of Economics of

the University of Ottawa in 2017. Shumakova used the Canadian Labour Force Survey data from

1979-2016 in an econometric model that can account for minimum wage with or without lag. The

paper considers teens (16-19) and young adults (20-24) for both genders together and separately.

15

The overall result is that a raise in the minimum wage has a negative and statistically significant

dis-employment of teens with a smaller effect on young adults. Specifically, “a 10% increase in

the minimum wage decreases the teenage employment rate by approximately 1.4%” for teens and

0.7 % for young adults. When the lag was considered in the model, it was found that the effect on

teens takes from 12 to 18 months to manifest and around 6 months for young adults although the

magnitude of the effect is unchanged. The results were separated by gender and the results for

males were slightly larger. The results were found to be robust using different measures.

Stevens. In “The Fight for a $15 Minimum Wage in Saskatchewan”, Stevens paints a

picture of how some organizations (unions, rank-and-file workers, students and community

members) are asking to raise the minimum wage while others (Canadian Federation of Independent

Business (CFIB) and business owners) are asking to reduce it. As well, some researchers support

the increase while others don’t. The CFIB claims that an increase to $15 an hour would result in

the loss of jobs (7,500 to 17,000 youth jobs). This is based on the simple yet unsubstantiated

formula that every 10% increase in the minimum wage will result in at 3% to 6% reduction of

employment of workers aged 15 to 19 (Wong, Queenie, 2017)7. The Financial Accountability

Office (FAO) in Ontario and TD Bank have published their assessment of phasing in the $15 per

hour minimum wage in Ontario. The assessment says the following: “As a tool to fight poverty,

the FOA concludes, the $15 hair hour minimum wage falls short of its intended goal, despite

boosting wages for over 1 million workers.” The increase in minimum wage could result in the

loss of 50,000 jobs which is about 0.7% of total employment as a consequence of the increased

payroll costs. If the 0.7% is applied to Saskatchewan, it means a loss of 3,245 jobs as opposed to

7

http://www.cfib-fcei.ca/cfib-documents/rr3445.pdf

16

the 7,500-17,000 jobs lost as claimed by the CFIB. Stevens concludes his paper by stating that

“the $15 campaign needs to be couched in a broader set of anti-poverty initiatives” such as more

progressive set of labor rights reforms (access to collective bargaining, living wages and secure

employment) to address “nearly a quarter of the province’s workplace employed in what are

typically low wage industries and occupations.”

Yusuff (2012) wrote his paper “Effects of Minimum Wage on Youth Employment and

School Enrollment in Canada” as a requirement for an M.A. degree at the Department of

Economics of the University of Lethbridge in 2012. The data used was from the Public Use of

Microdata of Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics over the period 2005-2011. The author

concluded that a 10 % increase in the minimum wage induces about 3.96 % decrease in employment

of low skilled workers especially youth (16-19). As well, it was found that an increase in the minimum

wage has a statistically significant positive correlation with school enrollment.

3.3.

International

Aras analyzed the effect of minimum wage level on labor efficiency in the countries

belonging to the OECD. The study used data of minimum wage and labor productivity from the

years between 1995 and 2011 and the estimations were made by panel data analysis method. It

was found that changes in the minimum wage had statistically significant effects on the labor

productivity. The study concludes that “The increase in minimum wage can raise the social

welfare by increasing the labor productivity, or an increase in labor productivity can lead to an

increase in minimum wage”. This is the problem, so few employees are directly affected by

minimum wage increases so that macro measurements are hard to do.

17

Cueto discusses how very poor countries deliberately depress wages to attain higher

competitiveness in the global market. This policy distorts the comparative advantage and induces

lower purchasing power which leads to suboptimal consumption. Additionally, the living

conditions of the working poor is unacceptable and so it is unethical. Some companies increase

the wages but they lose the competitiveness if done unilaterally. The authors found that a global

lower bound for minimum represents a Pareto Improvement by enhancing the markets due to the

expansion in sales caused by the increase in real wages of most workers.

Hara Examined the effects of minimum wages on formal and informal firm-provided

training and worker-initiated training in Japan. It was observed that a 1% increase in the minimum

wage causes a 2.8% decrease in the firm provided formal training for workers affected by

minimum wage increases but there was no statistically significant decrease of informal training.

Increasing the minimum wage did not increase worker-initiated training and therefore the overall

effect was a decrease in skill development for workers affected by minimum wages.

Jales estimated the effects of the minimum wage in a developing country with an economy

comprised of formal and informal workers. Informal workers are those that are not subject to the

national social security scheme and they would not benefit from increases in minimum wage. The

minimum wage causes an increase of approximately 16% on average wages; however, the

minimum wage generates large unemployment effects. The decrease is due to the unemployment

effects, which is about 9% and the movement of workers from the formal to the informal sector

raising it by 39%. Collectively, it reduces by approximately 6% the tax revenue collected by the

government to support the social welfare system.

18

Knabe analyzed how minimum wage affects employment, wage inequality, public

expenditure and aggregate income in the low-wage sector in Germany. The government could

achieve better employment and income effects with wage subsidies than with minimum wages

given the same spending on unemployment and welfare benefits. Installing minimum wage would

cost over 800,000 low paid jobs and increase fiscal spending by about EUR 4 billion while

household income rises only by EUR 1.1 billion per year. Complementing the minimum wage

with a wage subsidy, which is known as the “French Approach”, is only suitable for moderate

(EUR 5) statutory minimum wages. Wage subsidy by itself is superior to either implementing a

minimum wage by itself or a minimum wage complemented by a wage subsidy.

Kronenberg investigated the correlation between minimum wage and mental health in the

UK. The paper’s results show that there is no impact of minimum wage on mental health of low

wage earners and this is contrary to earlier research by others. To confirm the findings, the author

conducted several robustness checks and used alternative definitions of treatment and control

groups. To improve mental health, the author recommends that policies “should either consider

the non-wage characteristics of employment or potentially larger wage increases.”

Majchrowska analyzed the impact of minimum wage increase on gender wage gap in

Poland. The authors analyzed the impact for different age and educational groups in the private

sectors excluding those in agriculture. Overall, a significant increase in the minimum wage has a

positive impact on all age and educational groups. Specifically, it significantly decreased the wage

gap among young workers but had negligible impact on the wage gap for middle-aged workers.

The impact on wage gap among education groups where much smaller still. The results are in-line

19

with previous studies for both developed and developing countries as well as with the authors

intuition that’s the minimum wage increase mainly affects the workers for whom the minimum

wage is binding: those with low labor market experience and relatively poor qualifications. As

such, minimum wage policy could be used to decrease the gender wage gap; however, potential

dis-employment effects should be considered.

Saari estimated the impact of minimum wages on poverty across ethnic groups in Malaysia.

Unlike other countries whose lower income groups are usually associated with the minority in the

population, in Malaysia, the Malays who constitute the largest ethnic group, receive a lower

income share than the other relatively smaller ethnic groups. In 2005, the Malays per capita

monthly income was 63% and 26% lower than the per capita incomes of Chinese and Indians.

About 2.8 million workers (28%) in Malaysia were paid a monthly basic wage that was below the

poverty line as per data from 2005 and that constitutes a strong reason to introduce minimum wage

legislation. It was found that minimum wages potentially increase wages of the poor people which

reduces poverty for all ethnic groups. The percentage of formal workers in each ethnic group are:

66 % Malays, 74.2 % Chinese, 74.5 % Indian and 56.3 % others (Saari, Table 2). Hence, the Indian

ethnic group would benefit the most since about two-thirds are employed in the formal sector. The

results of this paper are highly relevant for the short run and they may no longer hold for the long

run due to the following factors. First, the interpretation of these results is highly sensitive to the

definition of informal workers (workers that are not subject to the national social security scheme;

46 % formal and 54 % informal). Second, the income effects will vary subject to the compliance

of the employers with the minimum wages. Finally, only the wage effects were considered while

the dis-employment effect was ignored.

20

Weng’s article does not research the effect of instituting a minimum wage on the economy

but instead it is about, and appropriately titled, “Re-examining the Urban Civilization Using the

Minimum Wage Level as an Alternative Value-Evaluation Basis”. Countries are trying to increase

the growth level by increasing the per capita income or GDP but these indicators omit the real

value of the human life quality and the environmental / ecological systems. The author proposes

to utilize the minimum wage level as a conversion basis to adjust the mainstream economic

indicator. Weng considers several megacities in east Asia including Tokyo, Osaka, Seoul, Beijing,

Shanghai, Guangzhou, Taipei and Hong Kong. The following ratios were used: Annual per capita

GDP/ Annual per capita minimum wage (indicator I), Annual per capita disposable income/

Annual per capita minimum wage (indicator II) and Annual per capita consumption expenditure/

Annual per capita minimum wage (indicator III) to propose an alternative perspective to reexamine the current mainstream value of civilization.

Considering just the per capita GDP, Tokyo stands at USD $66,136 and it is quite superior

to the other cities in descending order: Hong Kong (40,215), Seoul (33,229) and the lowest is

Shanghai (15,851). In contrast to using just the GDP, the indicators I, II, and III for Tokyo, Osaka,

Seoul and Hong Kong are lower than Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Taipei. Weng states:

“Per capita disposal income in Tokyo, Osaka and Hong Kong might not satisfy the

subsistence level; with regard to indicator III in those cities, the minimum wage level

representing the subsistence level of income is actually smaller than the individual’s current

consumption expenditure, indicating that consumption desire might be suppressed.”

21

In contrast, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou and Taipei might consume too much

expenditure than the subsistence level. Weng introduces another indicator as the ratio of Annual

per Capita consumption indicator / Annual per capita disposable income (indicator IV) and finds

that there are no significant differences in the value of indicator IV among all cities. Weng used as

well the per capita municipal solid waste (MSW) as an environmental indicator and observed that

Tokyo, Osaka, Taipei and Hong Kong are more environmentally friendly than the other cities

Seoul, Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou.

4.

Conclusion

Even though many studies show that a raise in the minimum wage will have a dis-

employment effect, most countries are legislating minimum wage and more and more are

connecting the increase in the minimum wage to the CPI.

In the US, there are approximately 2.2 million workers (2.7 %) with wages at or below the

minimum wage and most are female, above 20 years of age and work part time in the food industry.

the CBO report in 2014 shows that raising the minimum wage to either $9.00 or $10.10 would see

a loss of about 100,000 jobs and 500,000 respectively. The job losses could be as high as double

the figures (200,000 and 1,000,000). Overall, the increase in the minimum wage will move

300,000 - 900,000 people above the poverty line and increase aggregate family income by about

$ 2,000,000,000.

22

In Canada, there was 1.57 million (10 %) individuals earning the minimum wage in the

first quarter of 2018 as per Statistics Canada8. This contrasts with the 953,000 (6 %) in the first

quarter of 2017. This is not surprising as many employees were getting paid more than the previous

minimum wage but less than the new minimum wage so they are now classified as minimum wage

earners. The proportion minimum wage employees under the age of 25 fell from 52 % to 43 % and

those aged 35 to 64 increased from 25 % to 31 %. Raising the minimum wage will have a disemployment effect from 1-6 % (Yusuff at 3.96%, Rybczynski and Sen from1-4%, Shumakova at

1.4%, and Stevens from 3-6 %). Assuming a 4 % dis-employment effect means about 40,000 to

60,000 jobs lost (4 % x 1 to 1.57 million) which is similar to the estimate by Brouillette et al.

The cost incurred by employers will depend on the industry. The small business website9

states that highly automated businesses might have labor costs less than 10 % (as a percentage of

gross income) while retail is higher at about 15-20 %. Restaurants average around 30 % and service

business go as high as 50%. A 10 % raise in the minimum wage will at most increase the labor

cost for a business by 10 % if all its employees earn the minimum wage. Taking a food business

as an example with $ 1 million sales will have $300,000 as labor cost at 30 % and an increase of a

maximum of $ 30,000 in labor cost (10 % of $300,000).

International research has similar findings. Aras found that it (an increase in minimum

wage) raises social welfare and Cueto recommends it to increase purchasing power. Hara found

that the overall effect was a decrease in skill development for workers affected by minimum wages.

Jales found that it moves worker to the informal section and reduces taxes collected. Knabe

8

9

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/75-006-x/2018001/article/54974-eng.htm

https://smallbusiness.chron.com/much-gross-revenue-should-payroll-18985.html

23

recommends a wage subsidy over minimum wage. Kronenberg’s results show that there is no

impact of minimum wage on mental health of low wage earners and this is contrary to earlier

research by others. Majchrowska showed that it significantly decreased the wage gap among young

workers but had negligible impact on the wage gap for middle-aged workers. Saari recommended

a minimum wage increase to move many of the 2.8 million (28 %) workers above the poverty line.

Weng used the minimum wage as a conversion basis to adjust the mainstream economic indicator.

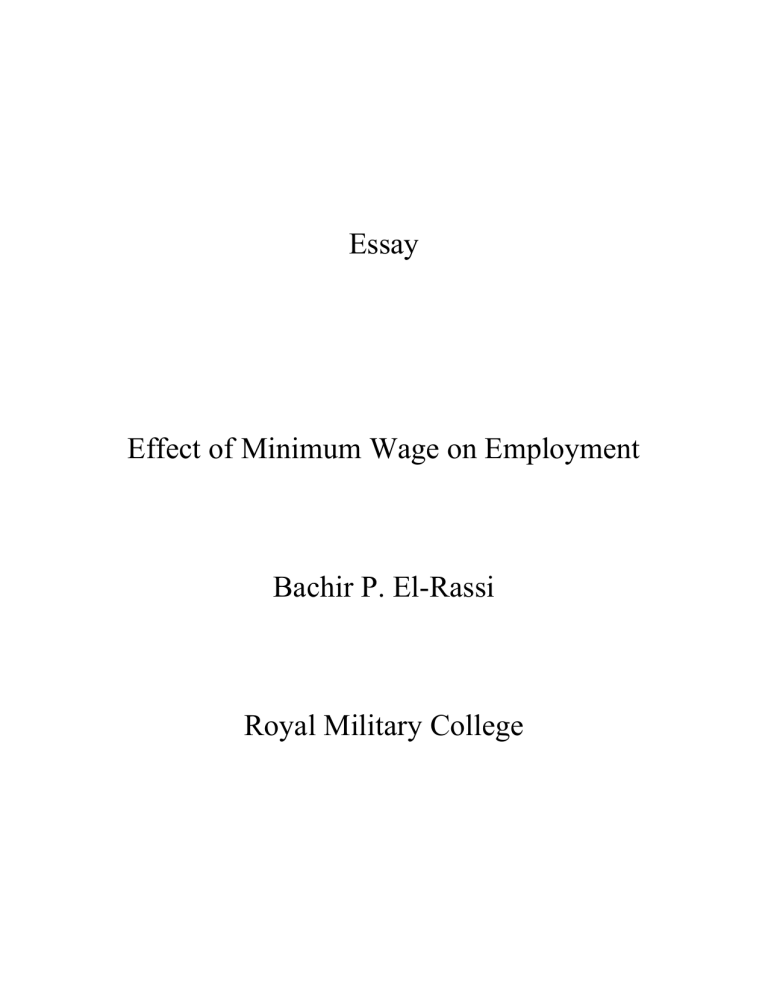

Table 1 below shows a summary of all the articles reviewed and what each article states

about the effects of raising the minimum wage on the various metrics. A “+” means that the author

found that a raise in the minimum wage positively affects that metric, a “0” (Zero) means neutral

effect and a “-” means it negatively affects that metric.

It seems the majority of the articles confirm that there is a dis-employment effect; however,

a wholistic approach that considers all the other metrics is best. Another point to note is that each

article had limitations on the data and the models they used to estimate the effect. Overall, an

increase in the minimum wage moves people above the poverty line and increases the family

income of those affected. Hiking a minimum wage redistributes income between heterogeneous

consumers (Brecher and Gross) and those minimum wage earners will spend their extra money

which stimulates the economy and increases demand.

24

Aras

Elmendorf, CBO

Knabe

+

Brecher

+

Brouillette

-

Cueto

-

-

Lau

-

Majchrowska

-

Rybczynski, Sen

-

Saari

-

Shumakova

-

Stevens

+

-

HARA

+

0

-

Jales

Kronenberg

0

+

+

Table 1 – Summary of articles’ findings

25

+

Social Welfare

Gender Wage Gap

Economic Growth

Poverty

Mental Health

Training, worker initiated

Training by Firm

Interest Rate

GDP

CPI

Employment

Labor Productivity

Taxes collected

+

In-Formal workers

+

Formal workers

+

+

-

References

Aras, E. 2015, Effect of minimum wage level on labor efficiency: An analysis on OECD countries,

Journal of International Management, Educational and Economics Perspectives 3 (2)

(2015) 1–11.

Bradley, D. (2017). The federal minimum age: in brief, USA Congressional Research Service 75700 -, R43089.

Brecher, R.A., Gross T. (2018). Employment gains from minimum-wage hikes under perfect

competition: A simple general-equilibrium analysis. Rev Int Econ., Wiley, 2018;26:165–

170. https://doi.org/10.1111/roie.12322, accessed 17 Dec 2018.

Brouillette D., Cheung C., Gao D., Gervais O. (2017). The impacts of minimum wage increase on

the Canadian economy, Bank of Canada, Staff Analytical Note 2017-26.

Cueto J.C. (2017). Reducing the race to the bottom: A primer on a global floor for minimum wages,

Investigacion Economica, vol LXXVI, num 300, abril-junio de 2017, pp. 33-51.

Elmendorf, D.W. (2014) CBO Director, The effects of a minimum-wage increase on employment

and family income, Congressional Budget Office, 44995

Elwell, C.K. (2014), Inflation and the real minimum wage: A fact sheet. USA Congressional

Research Service, 7-5700, www.crs.gov , R42973

Galarneau, D., Fecteau, E. (2014). The Ups and Downs of Minimum Wage.” Statistics Canada

Catalogue No. 75-006X. http://publications.gc.ca/site/eng/9.801310/publication.html

accessed 17 Dec 2018.

26

Hara, H. (2017). Minimum wage effects on firm-provided and worker-initiated training,

Department of Social and Family Economy, Faculty of Human Sciences and Design, Japan

Women's University, Labour Economics 47 (2017) 149–162.

Jales, H. (2016). Estimating the effects of the minimum wage in a developing country: A density

discontinuity design approach, Department of Economics and Center for Policy Research,

Syracuse University, DOI: 10.1002/jae.2586.

Knabe, A., Schöb, R. (2008). Minimum wage incidence: the case for Germany, Free University

Berlin, School of Business & Economics, CESifo Working Paper No. 2432.

Kronenberg, C., Jacobs, R., Zucchelli, E. (2017). The impact of the UK national minimum wage

on mental health, CINCH-Health Economics Research Center, University of DuisburgEssen, Germany, SSM - Population Health 3 (2017) 749–755.

Lau, M. (2018). Against the minimum wage, Bachelor of Commerce, specialization in finance and

economics, University of Toronto, Frontier Center for public policy, Winnipeg.

Majchrowska, M., Strawinski, P. (2018). Impact of minimum wage increase on gender wage gap:

case of Poland, Faculty of Economics and Sociology, Economic Modelling 70 (2018) 174–

185.

Riddel, W.C. (2016). The labor market in Canada, 2000–2016, University of British Columbia,

Canada, and IZA, Germany.

Rybczynski, K., Sen, A. (2017). Employment effects of the minimum wage: panel data evidence

from Canadian provinces, Contemporary Economic Policy, (ISSN 1465-7287) Vol. 36,

No. 1, January 2018, 116–135.

27

Saari, M.W., Affan Abdul Rahman, M., Hassan, A., Shah Habibullah, M. (2016). Estimating the

impact of minimum wages on poverty across ethnic groups in Malaysia, Faculty of

Economics and Agriculture, Economic Modelling 54 (2016) 490–502.

Shumakova, E. (2016). The effect of the minimum wage on the employment rate in Canada, 1979

– 2016, University of Ottawa, Department of Economics, M.A. paper (8494088).

Schwind, H.F., Uggerslev, K., Wagar, T.H., Fassina, N., Bulmash, J. (2016). Canadian Human

Resource Management, 11th Edition, McGrew Hill Education.

Stevens, A. (2017). The fight for a $15 minimum wage in Saskatchewan, University of Regina,

Associate professor.

Weng, Y.C. (2016). Re-examining the urban civilization using the minimum wage level as an

alternative value-evaluation basis, Procedia Engineering, Urban Transitions Conference,

Shanghai, 198 (2017) 1084 – 1091

Yusuff, O.M. (2012). Effects of minimum wage on youth employment and school enrollment in

Canada, Department of Economics, University of Lethbridge, Alberta.

28