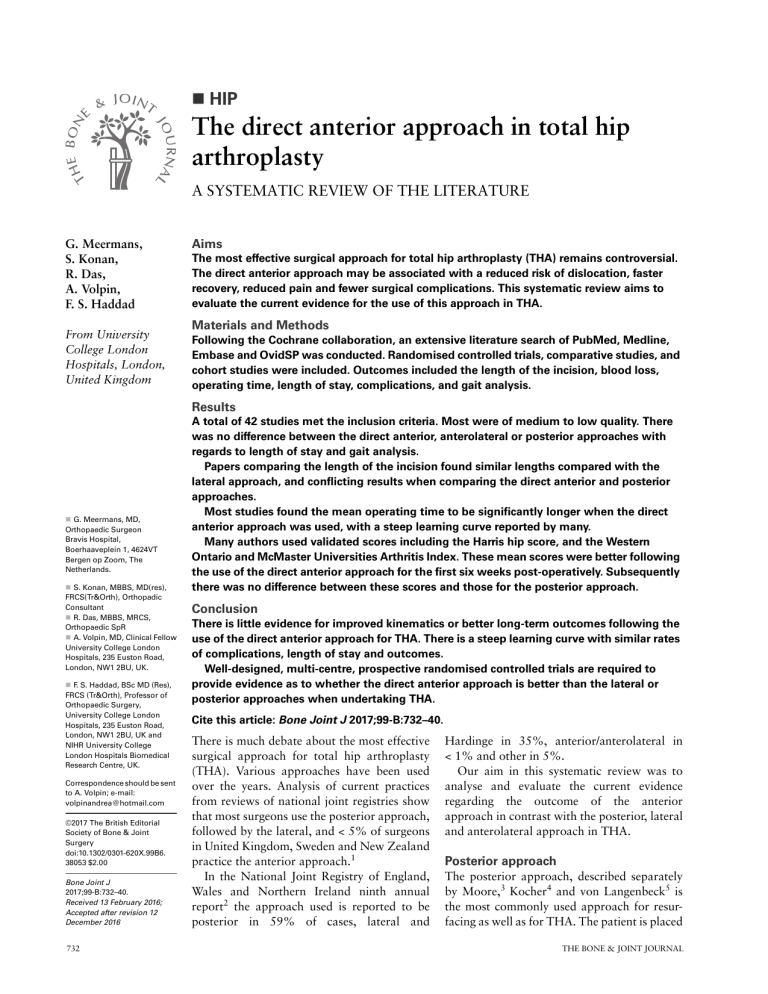

HIP The direct anterior approach in total hip arthroplasty A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE G. Meermans, S. Konan, R. Das, A. Volpin, F. S. Haddad From University College London Hospitals, London, United Kingdom Aims The most effective surgical approach for total hip arthroplasty (THA) remains controversial. The direct anterior approach may be associated with a reduced risk of dislocation, faster recovery, reduced pain and fewer surgical complications. This systematic review aims to evaluate the current evidence for the use of this approach in THA. Materials and Methods Following the Cochrane collaboration, an extensive literature search of PubMed, Medline, Embase and OvidSP was conducted. Randomised controlled trials, comparative studies, and cohort studies were included. Outcomes included the length of the incision, blood loss, operating time, length of stay, complications, and gait analysis. Results G. Meermans, MD, Orthopaedic Surgeon Bravis Hospital, Boerhaaveplein 1, 4624VT Bergen op Zoom, The Netherlands. S. Konan, MBBS, MD(res), FRCS(Tr&Orth), Orthopadic Consultant R. Das, MBBS, MRCS, Orthopaedic SpR A. Volpin, MD, Clinical Fellow University College London Hospitals, 235 Euston Road, London, NW1 2BU, UK. F. S. Haddad, BSc MD (Res), FRCS (Tr&Orth), Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery, University College London Hospitals, 235 Euston Road, London, NW1 2BU, UK and NIHR University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre, UK. Correspondence should be sent to A. Volpin; e-mail: volpinandrea@hotmail.com ©2017 The British Editorial Society of Bone & Joint Surgery doi:10.1302/0301-620X.99B6. 38053 $2.00 Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:732–40. Received 13 February 2016; Accepted after revision 12 December 2016 732 A total of 42 studies met the inclusion criteria. Most were of medium to low quality. There was no difference between the direct anterior, anterolateral or posterior approaches with regards to length of stay and gait analysis. Papers comparing the length of the incision found similar lengths compared with the lateral approach, and conflicting results when comparing the direct anterior and posterior approaches. Most studies found the mean operating time to be significantly longer when the direct anterior approach was used, with a steep learning curve reported by many. Many authors used validated scores including the Harris hip score, and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index. These mean scores were better following the use of the direct anterior approach for the first six weeks post-operatively. Subsequently there was no difference between these scores and those for the posterior approach. Conclusion There is little evidence for improved kinematics or better long-term outcomes following the use of the direct anterior approach for THA. There is a steep learning curve with similar rates of complications, length of stay and outcomes. Well-designed, multi-centre, prospective randomised controlled trials are required to provide evidence as to whether the direct anterior approach is better than the lateral or posterior approaches when undertaking THA. Cite this article: Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:732–40. There is much debate about the most effective surgical approach for total hip arthroplasty (THA). Various approaches have been used over the years. Analysis of current practices from reviews of national joint registries show that most surgeons use the posterior approach, followed by the lateral, and < 5% of surgeons in United Kingdom, Sweden and New Zealand practice the anterior approach.1 In the National Joint Registry of England, Wales and Northern Ireland ninth annual report2 the approach used is reported to be posterior in 59% of cases, lateral and Hardinge in 35%, anterior/anterolateral in < 1% and other in 5%. Our aim in this systematic review was to analyse and evaluate the current evidence regarding the outcome of the anterior approach in contrast with the posterior, lateral and anterolateral approach in THA. Posterior approach The posterior approach, described separately by Moore,3 Kocher4 and von Langenbeck5 is the most commonly used approach for resurfacing as well as for THA. The patient is placed THE BONE & JOINT JOURNAL THE DIRECT ANTERIOR APPROACH IN TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY 2654 potentially relevant studies identified and screened on title 2201 studies excluded after screening on title 453 potentially relevant studies screened on abstract 380 studies excluded after screening on abstract 76 studies screened on full text 42 studies included: - 3 with anterolateral approach as study contrast - 19 with lateral approach as study contrast - 20 with posterior approach as study contrast Fig. 1 Flowchart showing the selection of articles. in the lateral position and the incision is made over the posterior aspect of the greater trochanter. It has the benefit of not interfering with the abductor mechanism, however, there is a risk of damage to the sciatic nerve during dissection or compression under retractors, as it lies over the external rotator muscles. The inferior gluteal artery may be damaged as it leaves the pelvis beneath the piriformis and supplies the gluteus maximus muscle. The main disadvantage of this approach, reported in a meta-analysis of > 13 000 THAs is a rate of dislocation of about 3.23% for the posterior approach (3.95% without posterior repair and 2.03% with posterior repair), 2.18% for the anterolateral approach, and 0.55% for the direct lateral approach.6 Anterolateral and lateral approaches The anterolateral approach was described separately by Watson-Jones in 1936.7 The patient is placed in either the supine or lateral position and the plane between tensor fascia lata and gluteus medius is developed. The abductor mechanism must be released to allow adequate view of the anterior capsule of the hip. This release can be done either VOL. 99-B, No. 6, JUNE 2017 733 by a trochanteric osteotomy or a release of the gluteus medius. The direct lateral approach which was described by Hardinge in 19828 and also subsequently by Bauer et al,9 avoids the need for trochanteric osteotomy and the gluteus medius muscle is preserved. The risks associated with lateral approaches include injury to the superior gluteal nerve and heterotopic ossification.10 Direct anterior approach The direct anterior approach which was initially described by Hueter11 in 1870 and subsequently by Smith-Petersen et al12 and Judet and Judet,13 is associated with a reduced risk of dislocation, faster recovery, less pain and fewer surgical complications.14 With the patient in the supine position the interval between tensor fascia lata and sartorius is developed to access the hip. This avoids detachment of muscle from bone. The anterior approach is used commonly in paediatric surgery for developmental dysplasia of the hip. It is also being used increasingly for femoroacetabular impingement, hip resurfacing and to access the anterior aspect of the acetabulum.14,15 The disadvantages of the anterior approach are thought to include a steep learning curve and the need for further release of tendon and capsule,14,16 and the difficulty of using it in obese patients.15 Materials and Methods An extensive computerised literature search of EMBASE, MEDLINE OvidSP, Web of Science, Cochrane Central, PubMed Publisher and Google Scholar was conducted. The following combined key words were used: hip arthroplasty(ies)/replacement(s), minimally invasive/MIS/miniincision, and/or approach/anterior approach/direct anterior/Smith-Petersen/Hueter. The bibliographies of retrieved studies and other relevant publications, including reviews, were cross-referenced for additional potential articles. Inclusion criteria were: randomised controlled trials published in English; studies which included the anterior approach for THA and at least one of the following was assessed: surgical details including blood loss and operating time; length of in hospital stay; adverse events including complications; and radiographic outcomes including the number of acetabular components outside the desired alignment range. We excluded in vitro studies and cadaver studies. The selection was performed in two stages. The first, based on the title and abstract and taking into consideration the inclusion criteria, was independently performed by two reviewers (GM, RD). Disagreements were resolved by consensus (Fig. 1). Secondly, the quality of each study which was included was assessed by two independent reviewers (AV and SK). The risk of bias was investigated using a standardised set of 734 G. MEERMANS, S. KONAN, R. DAS, A. VOLPIN, F. S. HADDAD Table I. Quality assessment Question Response Is there a clearly stated aim? Did they have a “study question” or “main aim” or “objective”? The question addressed should be precise and relevant in light of available literature. To be scored adequate the aim of the study should be coherent with the “Introduction” of the paper. Did the authors say: “consecutive patients” or “all patients during period from … to….” or “all patients fulfilling the inclusion criteria”? Did the authors report the inclusion and exclusion criteria? Did they say “prospective”, “retrospective” or “follow-up”? Inclusion of consecutive patients A description of inclusion and exclusion criteria Prospective collection of data. Data were collected according to a protocol established before the beginning of the study The study is NOT PROSPECTIVE when: chart review, database review, clinical guideline, practical summaries. Surgical technique description Did they report the surgical technique description? Outcome measures Did they report outcome measures to evaluate patients after the operation? Unbiased assessment of the study outcome and determinants To be judged as adequate the following 2 aspects had to be positive: - Outcome and determinants had to be measured independently - Both for cases and controls the outcome and determinants had to be assessed in the same way Were the determinant measures used accurate (valid and For studies where the determinant measures are shown to be valid and reliable, the reliable)? question should be answered adequate. For studies, which refer to other work that demonstrates the determinant measures are accurate, the question should be answered as adequate. Loss to follow-up Did they report the losses to follow-up? Adequate statistical analysis Was an adequate statistical analysis performed? criteria based on modified questions of existing quality assessment tools (Table I). When the criterion was met in the study, one point was given, otherwise zero points. Zero points were also given when information concerning the specific criterion was not mentioned. A maximum score of ten points could be obtained; studies were considered of high methodological quality if a total score of more than six points was obtained. Each study was independently assessed for its design and methodology and level of evidence, assessed by two authors (AV and SK) (Supplementary Table i). The following data were extracted from each study: the authors, the journal and year of publication, the surgical approaches, use of traction table, intra-operative fluoroscopy, patient selection and the number of patients. Intraoperative details of length of incision, operating time, blood loss, post-operative details included pain, recovery from surgery, post-operative rehabilitation, length of stay, gait analysis, follow-up and complications were all analysed. There were significant differences in study design and outcome measures. We analysed each outcome measure separately. In order to compare studies, a review was undertaken in accordance with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines.16 A total of 42 studies were used for this systematic review, however several studies did not report all descriptive statistics for all outcomes, or did not include that particular outcome measure in the study. Case series studies were excluded. The studies which were included in the review are shown in Supplementary Table ii. Statistical analysis. In order to compare studies, effect sizes were, derived from means and standard deviations (SD), and Cohen’s kappa was calculated when all information was available. The latter were plotted as charts and tables. Results The assessment of the risk of bias. One study had a high risk of bias; the remaining had a low risk of bias (Table II).17-55 Incision. A number of authors compared the length of incision of the direct anterior and the lateral approaches. Hozak and Klatt17 found similar mean lengths of 10 cm. However, Sebečić et al18 and Sendtner et al19 noted shorter mean lengths of 7.5 cm and 8.5 cm, respectively in the direct anterior approach (p < 0.01). In the first retrospective non-randomised study20 there were 35 patients in each arm, while the second19 had 74 patients treated with the direct anterior approach and 60 patients treated with a lateral approach. We did not find any data comparing the lengths of the incisions in the anterolateral and direct anterior approaches. Studies comparing the direct anterior approach with the posterior approach have usually found the incision to be shorter in the direct anterior approach. Pilot et al20 compared ten patients in each arm of a prospective study and found that the mean length of the incision for the posterior approach was 17.5 cm versus 8.6 cm for the direct anterior approach (p < 0.001). Martin et al21 concurred, with a mean length of 19.2 cm for the posterior approach versus 11 cm for the direct anterior approach (p < 0.0001). There was evidence of selection bias in this study as patients with THE BONE & JOINT JOURNAL THE DIRECT ANTERIOR APPROACH IN TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY 735 Table II. The assessment of the risk of bias Study Criteria Hananouchi et al10 Barrett et al14 Nam et al15 Hozack and Klatt17 Sebečić et al18 Sendtner et al19 Pilot et al20 Martin et al21 Rodriguez et al22 Bergin et al23 Berend et al24 D'Arrigo et al25 Alecci et al26 Nakata et al27 Ilchmann et al28 Mayr et al29 Seng et al30 Wayne and Stoewe31 Rathod et al32 Schweppe et al33 Spaans et al34 Zawadsky et al35 Restrepo et al36 Pogliacomi et al37 Pogliacomi et al38 Taunton et al39 Amlie et al40 Maffiuletti et al41 Klausmeier et al42 Lamontagne et al43 Varin et al44 Ward et al45 Rathod et al46 Reininga et al47 Parvizi et al48 Baba et al49 Bremer et al50 Christensen et al51 Goebel et al52 Lugade et al53 Sugano et al54 Yi et al55 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 higher body mass index (BMI) were selected to have surgery using a posterior approach due to the difficulty of using direct anterior approach in the obese patient. The mean BMI was 34.1 in those in whom a posterior approach was used and 28.5 in those in whom a direct anterior approach was used (p < 0.0001). The studies comparing the direct anterior and the posterior approaches did not distinguish between an extended posterior approach and a modified minimally invasive posterior approach.22 The latter is more commonly used today.22 The length of the incision does not reflect the underlying soft-tissue trauma and caution should be exercised in its use as a marker for invasiveness. VOL. 99-B, No. 6, JUNE 2017 Total 3 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 4 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 5 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 6 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 7 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 0 0 8 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 9 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 0 10 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 6 10 8 7 5 8 7 9 10 7 7 9 8 9 7 8 6 6 8 8 9 7 9 7 6 9 8 7 9 9 7 6 8 9 7 6 7 6 8 8 6 6 Other studies comparing the direct anterior and posterior approaches had smaller margins of difference between the lengths of incision lengths. Barrett et al14 found that incisions were a mean of 1 cm shorter when the posterior approach was used. In a study of 57 patients, Bergin et al23 reported that the mean length of incision was 15.4 cm in the posterior approach and 12.1 cm in the direct anterior approach (p < 0.001). Operating time. The operating time was recorded in 25 studies10,14,18-38,48 and the consensus was that the direct anterior approach took longer than either the lateral, anterolateral or posterior approaches (Tables III and IV). Berend et al24 found that the operating times were initially 736 G. MEERMANS, S. KONAN, R. DAS, A. VOLPIN, F. S. HADDAD Table III. Mean operating time in minutes, direct anterior approach (DAA) versus anterolateral and lateral approaches (AL/L) (standard deviation if included) 180 160 Study DAA AL/L Hozack and Klatt17 Sebečić et al18 Sendtner et al19 Berend et al24 D’Arrigo et al25 Alecci et al26 Ilchmann et al28 Mayr et al29 Seng et al30 Wayne and Stoewe31 Restrepo et al36 Pogliacomi et al37 Pogliacomi et al38 Parvizi et al48 57 85 77 (16) 69 121 (23.6) 89 (19) 119 70 73 115 56 93 111 140 (27.38) 55 78 69 (25) 68 77 (15.1) 81 (15) 07 70 56 98 54 90 85 130 (24.68) DAA Lat AL Mean operative time (mins) 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Hozack17 Mayr29 Seng30 Berend24 Pogliacomi37 Sebeèiæ18 Alecci26 D’Arrigo25 IIchmann28 Restrepo36 Sendtner19 Wayne31 Parvizi48 Fig. 2 Graph showing mean operating times for the direct anterior approach (DAA) versus lateral (Lat) and anterolateral (AL) (standard deviation bars). longer but this difference disappeared during the study period and represented the learning curve of the technique. Their anterior supine intermuscular approach took a mean of 69 minutes versus 68 minutes for the less invasive direct lateral approach (p = 0.7). One study showed a high effect size for the difference in operating times between the direct anterior and posterior approaches. D'Arrigo et al25 reported a significantly increased operating time, again thought to be due to the learning curve associated with the direct anterior approach. They found a significantly longer operating time in the first ten cases than in the second ten cases (p = 0.013) (Figs 2 and 3).56 Blood loss. Blood loss was recorded in various ways, including change in serum haemoglobin level, intraoperative measurement of blood loss and the number of units of post-operative transfusion. Alecci et al26 recorded a difference between the mean levels of haemoglobin pre-operatively and on the first postoperative day of 3.5 g/dL (SD 1) in the lateral approach group versus 3.1 g/dL (SD 0.9) in the anterior approach group (p < 0.0005). They also recorded that 7.5% of patients in the lateral group had an intra-operative blood transfusion compared with 1.8% in the anterior group (p = 0.008). A total of 85 patients (40%) in the lateral groups had a post-operative blood transfusion and 44 THE BONE & JOINT JOURNAL THE DIRECT ANTERIOR APPROACH IN TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY 180 Mean operative time (mins) 160 737 DAA Post 140 120 100 80 60 40 20 0 Bergin23 Pilot20 Martin21 Ratho46 Schweppe35 Zawadsky35 14 10 27 Barrett Hananouchi Nakata Poehling- Rodriguez36 Spaans34 Monaghan56 Fig. 3 Graph showing mean operating times for the direct anterior approach (DAA) versus posterior (Post) (standard deviation bars). (19%) in the direct anterior group. There was a statistically significant difference between the two groups in the volumes of intra-operative colloid and crystalloid infusion (p < 0.0005). The use of intravenous fluids may clearly confound the reported blood loss. D'Arrigo et al25 recorded a mean blood loss of 1219 ml (SD 786.5) in the lateral minimally invasive (MIS) group, 1344 ml (SD 710.0) in the anterior MIS group, 1279 ml (SD 694.9) in the anterolateral MIS group and 1644 ml (SD 757.7) in standard lateral group for a total of 60 patients enrolled in the study. In the comparison of the first three groups, no statistically significant difference was found (p > 0.05), however they were all significantly less than the blood loss in the standard lateral group. The technique used to measure blood loss was from Rosencher et al.57 Nakata et al27 found a statistically significant increase in blood loss in the direct anterior group (99 hips). The mean intra-operative blood loss was 526.1 ml in the direct anterior group and 426.9 ml in the mini-posterior group (p= 0.46). This was thought to be due either to technical difficulties in femoral preparation or a steep learning curve. When compared with the posterior approach, Bergin et al,23 Hananouchi et al10 and Martin et al21 did not find a statistically significant difference in blood loss. No study considered the confounding factors that should be allowed for or kept consistent in both arms of the study. The pre-operative level of haemoglobin and medical comorbidities play a role in the loss of blood. It is not possible from these studies to draw conclusions about which of the surgical approaches is associated with the least blood loss (Table V). Length of stay. A total of 12 studies.17,18,22,24-28,30,32,34,36 looked into the effect of the surgical approach on the length of stay as a measure of recovery. Most concluded that the length of VOL. 99-B, No. 6, JUNE 2017 stay is not significantly related to the approach. Many authors reported a difference in length of stay of < 24 hours between various surgical approaches.17,22,24,26,28,30,33,34,36 The mean length of stay was between two and five days in most studies. The length of stay was significantly longer in the studies which reported a difference between approaches. Alecci et al26 reported a mean length of stay of ten days (SD 3.5) for THAs undertaken through a lateral approach and seven days (SD 2) for those undertaken through direct anterior approaches, which was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Nakata et al27 recorded a mean length of stay of 30.4 days (SD 1.2) for those undertaken using a posterior approach and 22.2 days (SD 1.4) for those using a direct anterior approach (p = 0.003). Sebečič et al18 reported that patients whose THA was undertaken through an anterior approach were discharged from hospital a mean of two days earlier than those undertaken through a lateral approach. Post-operative recovery. The most common measures of outcome which were used were the Harris hip score (HHS)17 and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC).37,59 These were used in 13 studies.14,18,19,22,25,28,30,34,36,37-40 Higher WOMAC scores indicate worse pain, stiffness and functional limitations. Amlie et al40 compared various indicators of outcome and found that the WOMAC score was comparable in patients whose THA had been undertaken using the direct anterior and posterior approaches and better than those using the anterolateral approach. The mean HHSs were better for the direct anterior approach in some studies.32,37,41 Seng et al30 reported a mean HHS of 81 in those with a direct anterior approach and 75 in those with a lateral approach. (p < 0.0001). Sebečič et al18 found similar mean HHSs in those 738 G. MEERMANS, S. KONAN, R. DAS, A. VOLPIN, F. S. HADDAD Table IV. Mean operating time in minutes, direct anterior approach (DAA) versus posterior (standard deviation if included) Study DAA Posterior Hananouchi et al10 Barrett et al14 Pilot et al20 Martin et al21 Rodriguez et al22 Bergin et al23 Nakata et al27 Rathod et al32 Schweppe et al33 Spaans et al34 Zawadsky et al35 129 84 (12.4) 99.5 141 (22) 90(15) 78 (17.9) 104.7 90 109 84 102.7 (20.9) 115 60 (12.4) 81 114 (22) 85 (14) 118 (19.4) 100.4 84 102 46 (9) 87.8 (20) Table V. Blood loss Barrett et al14 Bergin et al23 Nakata et al27 Spaans et al34 Pogliacomi et al37 Pogliacomi et al38 Effect size Cohen d 0.52 0.142 0.724 0.463 -0.105 -0.461 1.21 0.288 2.1 1.044 -0.211 -1.03 undertaken with a direct anterior approach and those with lateral approach (80 versus 69), two months postoperatively (p < 0.01). Four months post-operatively, this difference had narrowed to 92 versus 88 without statistical significance. Other authors concurred with the conclusion that the HHS improves initially, but these benefits are not continued into the longer term.8,24,39 Pogliacomi et al37 found a mean HHS of 91 in the direct anterior group versus 89 in the lateral group at one-year follow-up. Barrett et al14 compared the direct anterior and posterior approaches and also found initial improvements in the mean HHS, six weeks post-operatively (89.5 versus 81.4) (p < 0.0001). They suggested that the benefits of DAA might be seen only in the period immediately following surgery, in fact the mean scores were comparable at three months, six months and one year post-operatively. Taunton et al39 again found similar mean HHSs up to a year postoperatively in the direct anterior and posterior groups. The mean WOMAC scores were inferior in the posterior group (87.2 versus 91.5) (p = 0.043). Four other studies23,29,34,43 recorded similar functional scores between the direct anterior and posterior approaches. Gait analysis. Few authors recorded gait analysis.43-48 Klausmeier et al42 undertook a small non-randomised study with 12 patients having a THA using a direct anterior approach, 11 using an anterolateral approach and a control group of ten patients. Pre-operatively the patients in both the direct anterior and anterolateral groups had reduced strength of the hip and gait when compared with controls. There were no statistically significant differences between the two approaches for most of the measurements of isometric strength and dynamic measurements of gait at six or 16 weeks, post-operatively. The measurements of strength and gait in both groups were reduced when compared with the controls. There was no direct measurement of flexion of the hip which would be the most affected activity by the direct anterior approach and the follow-up was too short to draw conclusions. Two studies18,40reported that patients who have undergone THA have abnormal kinematics on climbing stairs, regardless of surgical approach. The group having a THA using a direct anterior approach, however, had fewer differences compared with a normal control group, and their magnitude was usually less than in those who had a THA using a direct lateral approach. Patients in the direct anterior group were slightly better at climbing stairs. This study was not randomised and there was a mean age difference of about six years between the two groups (60.5 in the direct anterior group and 66 in the lateral group) and different uncemented components were used in the two groups. Both are confounding variables. Four studies21,45-47 reported similar post-operative gait analyses between THAs undertaken using the direct anterior and posterior approaches. Various authors21,45-47 agree that prior to THA, patients change their pattern of gait to reduce the pain and this pre-operative adjustment and alteration of muscle mass will contribute to the post-operative function. Discussion In this study, we analysed studies from the literature dealing with the anterior, anterolateral and posterior approaches to the hip joint. Several criteria were analysed and we were not able to identify any superiority for the use of the direct anterior approach in THA. A previous review60 has compared the direct anterior and lateral and posterior approaches. A comparison with the anterolateral approach has been included in this review article. Many outcome measures were investigated. The length of the incision was used as a surrogate for an assessment of invasiveness. Soft-tissue dissection, release and inadvertent injury play an important role in the outcome following THA.42 Operating times varied and there was a statistically significant increase in operating time for the direct anterior approach. A steep learning curve for this approach has been described,40 leading to complications that were rarely seen in other approaches such as breaching the femoral canal.31 This may be related to a learning curve or simply to an inadequate exposure. The reporting of blood loss in nonrandomised studies showed no evidence of accounting for confounding variables. However, as reported by Parvizi et al,48 less blood loss is associated with an anterior approach compared with a direct lateral approach, in which the incision is longer with more soft-tissue dissection, and the abductor muscles are violated. With the use of modern anaesthetic techniques and the routine use of tranexamic acid there should be minimal THE BONE & JOINT JOURNAL THE DIRECT ANTERIOR APPROACH IN TOTAL HIP ARTHROPLASTY blood loss irrespective of the surgical approach. The nature of the rehabilitation protocol required for discharge varied throughout the studies. Length of stay is affected by many issues including local protocols, the decisions of the surgeon, enhanced recovery pathways, society’s culture and expectations, the requirements of insurance companies, the pressures on beds and the destination at discharge.61 Most studies concluded that the short-term results favoured the direct anterior approach. Amlie et al40 reported that 107 patients (25%) who underwent THA using a lateral approach described developing a limp postoperatively. This was more than twice as many as in those who underwent THA using the direct anterior or posterior approaches. Limping had a serious effect on the patients’ ability to return to recreation and sports. Moreover, as reported by Sebeči et al,18 patients whose THA was undertaken using an anterior approach could walk without crutches eight days after surgery. However, in the mid- and long-term this benefit was negligible. Most studies did not assess outcome more than one year post-operatively. The studies of gait analysis did not include pre-operative assessment or the analysis of patterns of muscle activation using electromyography. Lamontagne et al43 showed that patients whose THA was undertaken using a direct anterior approach had kinematics which were slightly closer to normal those whose operation was undertaken using a lateral approach. However, no comparison was made with the posterolateral approach. This review has several limitations. Our findings were similar to those of previous reviews,1,60 however, we included more studies and we attempted to compare the surgical approaches in this review article. The main limitation of this review is that the papers which were included were single centre studies with heterogeneity of surgical technique, length of follow-up and outcomes scores. More randomised large multi-centre controlled trials, comparing the three surgical approaches, might provide an answer to which is the best approach when performing a THA. In conclusion, the current evidence does not support the recent enthusiasm for the use of the direct anterior approach. It offers an intermuscular plane, but has a considerable learning curve. However, it seems that the anterolateral approach which compromises the abductor mechanism does not offer any particular advantage. The question that still remains unanswered is which of the abductor sparing direct anterior and posterior approaches offers a significant advantage to the patient. Take home message: - To date, there is no real evidence that the direct anterior approach of the hip represents a better approach compared with the lateral or posterior approaches for performing a THA. VOL. 99-B, No. 6, JUNE 2017 739 Supplementary material Tables showing levels of evidence and randomisation of direct anterior approach versus lateral and versus posterior approachs are available alongside the online version of this article at www.bjj.boneandjoint.org.uk Author contributions: G. Meermans: Participated in the conception and design of the study, Acquisition of data, Analysed and interpreted the data, Drafted the manuscript. S. Konan: Drafted and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. R. Das: Involved in the acquisition of data, Interpretation of the data, Drafted the manuscript. A. Volpin: Drafted and revised the manuscript. F. S. Haddad: Jointly conceived the study, Participated in its design, Interpreted the data, Drafted and revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. This research/study/project was supported by the National Institute for Health Research University College London Hospitals Biomedical Research Centre. No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party related directly or indirectly to the subject of this article. This article was primary edited by J. Scott. References 1. Yue C, Kang P, Pei F. Comparison of Direct Anterior and Lateral Approaches in Total Hip Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA). Medicine (Baltimore) 2015;94:2126. 2. No authors listed. National Joint Registry http://www.njrcentre.org.uk/njrcentre/ Portals/0/Documents/England/Reports/9th_annual_report/ NJR%209th%20Annual%20Report%202012.pdf (date last accessed 19 April 2017). 3. Moore AT. Metal hip joint; a new self-locking vitallium prosthesis. South Med J 1952;45:1015–1019. 4. Kocher T. Textbook of Operative Surgery. 3rd English Ed. Macmillan, New York;1911:33–34. 5. von Langenbeck B. Chirurgische Beobachtungen aus dem Kriege. Hirschwald, Berlin: 1874. 6. Masonis JL, Bourne RB. Surgical approach, abductor function, and total hip arthroplasty dislocation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;405:46–53. 7. Watson-Jones R. Fractures of the neck of the femur. Br J Surg 1936; 23:787–808. 8. Hardinge K. The direct lateral approach to the hip. J Bone Jointt Surg [Br] 1982;64:17–19. 9. Bauer R, Kerschbaumer F, Poisel S, Oberthaler W. The transgluteal approach to the hip joint. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1979;95:47–49. 10. Hananouchi T, Takao M, Nishii T, et al. Comparison of navigation accuracy in THA between the mini-anterior and -posterior approaches. Int J Med Robot 2009;5:20–25. 11. Hueter C. Grundriss der Chirurgie. 2. Leipzig: FCW Vogel; 1883:129–200. 12. Smith-Petersen MN, Larson CB, et al. Complications of old fractures of the neck of the femur; results of treatment of vitallium-mold arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1947;29-A:41–48. 13. Judet J, Judet H. Anterior approach in total hip arthroplasty. Presse Med 1985;14:1031–1033. (In French) 14. Barrett WP, Turner SE, Leopold JP. Prospective randomized study of direct anterior vs postero-lateral approach for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013;28:1634–1638. 15. Nam D, Sculco PK, Abdel MP, et al. Leg-length inequalities following THA based on surgical technique. Orthopedics 2013;36:395–400. 16. Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1–34. 17. Hozack W, Klatt BA. Minimally invasive two-incision total hip arthroplasty: is the second incision necessary? Semin Arthrop 2008;19:205–208. 18. Sebečić B, Starešinić M, Culjak V, Japjec M. Minimally invasive hip arthroplasty: advantages and disadvantages. Med Glas (Zenica) 2012;9:160–165. 19. Sendtner E, Borowiak K, Schuster T, et al. Tackling the learning curve: comparison between the anterior, minimally invasive and the lateral, transgluteal approach for primary total hip arthroplasty. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2011;131:597–602. 20. Pilot P, Kerens B, Draijer WF, et al. Is minimally invasive surgery less invasive in total hip replacement? A pilot study. Injury 2006;37:S17–S23. 740 G. MEERMANS, S. KONAN, R. DAS, A. VOLPIN, F. S. HADDAD 21. Martin CT, Pugely AJ, Gao Y, Clark CR. A comparison of hospital length of stay and short-term morbidity between the anterior and the posterior approaches to total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2013;28:849–854. 22. Rodriguez JA, Deshmukh AJ, Rathod PA, et al. Does the direct anterior approach in THA offer faster rehabilitation and comparable safety to the posterior approach? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:455–463. 23. Bergin PF, Doppelt JD, Kephart CJ. Comparison of minimally invasive direct anterior versus posterior total hip arthroplasty based on inflammation and muscle damage markers. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2011;93-A:1392–1398. 24. Berend KR, Lombardi AV Jr, Seng BE, Adams JB. Enhanced early outcomes with the anterior supine intermuscular approach in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2009;91-A:107–120. 25. D’Arrigo C, Speranza A, Monaco E, Carcangiu A, Ferretti A. Learning curve in tissue sparing total hip replacement comparison between different approaches. J Orthop Traumatol 2009;10:47–54. 26. Alecci V, Valente M, Crucil M, et al. Comparison of primary total hip replacements performed with a direct anterior approach versus the standard lateral approach: perioperative findings. Orthop Traumatol 2011;12:123–129. 27. Nakata K, Nishikawa M, Yamamoto K, Hirota S, Yoshikawa H. A clinical comparative study of the direct anterior with mini-posterior approach: two consecutive series. J Arthroplasty 2009;24:698–704. 28. Ilchmann T, Gersbach S, Zwicky L, Clauss M. Standard transgluteal versus minimal invasive anterior approach in hip arthroplasty: a prospective, consecutive, cohort study. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2013;5:31. 29. Mayr E, Nogler M, Benedetti MG, et al. A prospective randomized assessment of earlier functional recovery in THA patients treated by minimally invasive direct anterior approach: a gait analysis study. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2009;24:812–818. 30. Seng BE, Berend KR, Ajluni AF, Lombardi AV Jr. Anterior-supine minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty: defining the learning curve. Orthop Clin North Am 2009;40:343–350. 31. Wayne N, Stoewe R. Primary THA: a comparison of the lateral hardinge approach to an anterior mini-invasive approach. Orthop Rev (Pavia) 2009;1:27. 32. Rathod PA, Bhalla S, Deshmukh AJ, Rodriguez JA. Does fluoroscopy with anterior hip arthroplasty decrease acetabular cup variability compared with a nonguided posterior approach Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:1877–1885. 33. Schweppe ML, Seyler TM, Plate JF, Swenson RD, Lang JE. Does surgical approach in total hip arthroplasty affect rehabilitation, discharge disposition and readmission rate? Surg Technol Int 2013;23:219–227. 34. Spaans AJ, van den Hout JA, Bolder SB. High complication rate in the early experience of minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty by the direct anterior approach. Acta Orthop 2012;83:342–346. 35. Zawadsky MW, Paulus MC, Murray PJ, Johansen MA. Early outcome comparison between the direct anterior approach and the mini-incision posterior approach for primary total hip arthroplasty: 150 consecutive cases. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1256–1260. 36. Restrepo C, Parvizi J, Pour AE, Hozack WJ. Prospective randomized study of two surgical approaches for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2010;25:671–679. 37. Pogliacomi F, De Filippo M, Paraskevopoulos A, et al. Mini incision direct lateral approach versus anterior mini invasive approach in total hip replacements: results 1 year after surgery. Acta Biomed 2012; 83:114–121. 38. Pogliacomi F, Paraskevopoulos A, Costantino C, Marenghi P, Ceccarelli F. Influence of surgical experience in the learning of a new approach in hip replacement: anterior mini-invasive vs. standard lateral. Hip Int 2012;22:555–561. 39. Taunton MJ, Mason JB, Odum SM, et al. Direct anterior total hip arthroplasty yields more rapid voluntary cessation of all walking aids: a prospective, randomized clinical trial. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:169–172. 40. Amlie E, Havelin LI, Furnes O, et al. Worse patient-reported outcome after lateral approach than after anterior and posterolateral approach in primary hip arthroplasty. A cross-sectional questionnaire study of 1,476 patients 1-3 years after surgery. Acta Orthop 2014;85:463–469. 41. Maffiuletti NA, Impellizzeri FM, Widler K, et al. Spatiotemporal parameters of gait after total hip replacement: anterior versus posterior approach . Orthop Clin North Am 2009;40:407–415. 42. Klausmeier V, Lugade V, Jewett BA, Collis DK, Chou LS. Is there faster recovery with an anterior or anterolateral THA? Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:533–541. 43. Lamontagne M, Varin D, Beaulé PE. Does the anterior approach for total hip arthroplasty better restore stair climbing gait mechanics. J Ortho Res 2011;29:1412– 1417. 44. Varin D, Lamontagne M, Beaulé PE. Does the anterior approach for THA provide closer-to-normal lower-limb motion? J Arthroplasty 2013;28:1401–1407. 45. Ward SR, Jones RE, Long WT, Thomas DJ, Dorr LD. Functional recovery of muscles after minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty. Instr Course Lect 2008;57:249– 254. 46. Rathod PA, Orishimo KF, Kremenic IJ, Deshmukh AJ, Rodriguez JA. Similar improvement in gait parameters following direct anterior and posterior approach total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1261–1264. 47. Reininga IH, Stevens M, Wagenmakers R, et al. Comparison of gait in patients following a computer-navigated minimally invasive anterior approach and a conventional posterolateral approach for THA: a randomized controlled trial. J Ortho Res 2013;31:288–294. 48. Parvizi J, Rasouli MR, Jaberi M, et al. Does the surgical approach in one stage bilateral total hip arthroplasty affect blood loss. Int Orthop 2013;37:2357–2362. 49. Baba T, Homma Y, Takazawa N, et al. Is urinary incontinence the hidden secret complications after total hip arthroplasty? Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2014;24:1455–1460. 50. Bremer AK, Kalberer F, Pfirrmann CW, Dora C. Soft-tissue changes in hip abductor muscles and tendons after total hip replacement: comparison between the direct anterior and the transgluteal approaches. J Bone Joint Surg [Br] 2011;93-B:886–889. 51. Christensen CP, Karthikeyan T, Jacobs CA. Greater prevalence of wound complications requiring repoeration with direct anterior approach total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1839–1841. 52. Goebel S, Steinert AF, Schillinger J, et al. Reduced postoperative pain in total hip arthroplasty after minimal-invasive anterior approach. Int Orthop 2012;36:491–498. 53. Lugade V, Wu A, Jewett B, Collis D, Chou LS. Gait asymmetry following an anterior and anterolateral approach to total hip arthroplasty. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2010;25:675–680. 54. Sugano N, Takao M, Sakai T, et al. Comparison of mini-incision THA through an anterior approach and a posterior approach using navigation. Orthop Clin North Am 2009;40:365–370. 55. Yi C, Agudelo JF, Dayton MR, Morgan SJ. Early complications of anterior supine intermuscular total hop arthroplasty. Orthopedics 2013;36:276–281. 56. Poehling-Monaghan KL, Kamath AF, Taunton MJ, Pagnano MW. Direct anterior versus miniposterior THA with the same advanced perioperative protocols: surprising early clinical results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015;473:623–631. 57. Rosencher N, Kerkkamp HE, Macheras G, et al. Orthopedic surgery transfusion hemoglobin European overview (OSTHEO) study: blood management in elective knee and hip arthroplasty in Europe. Transfusion 2003;43:459–469. 58. Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1969;51-A:737–755. 59. Bellamy N, Campbell J, Stevens J, et al. Validation study of a computerized version of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities VA3.0 Osteoarthritis Index J Rheumatol 1997;24:2413–2415. 60. Higgins BT, Barlow DR, Heagerty NE, Lin TJ. Anterior vs. posterior approach for total hip arthroplasty, a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Arthroplasty 2015;30:419–434. 61. Malek IA, Royce G, Bhatti SU, et al. A comparison between the direct and anterior and posterior approaches for total hip arthroplasty: the role of an ‘enhanced recovery’ pathway. Bone Joint J 2016;98-B:754–760. THE BONE & JOINT JOURNAL