219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 219

After Dunkirk: The French

Army’s Performance against ‘Case Red’, 25 May to 25 June 1940

Martin S. Alexander

The historiography of the German defeat of France and her allies in 1940 has focused mainly on the first fortnight of what was a six-week campaign.

Most writers have concentrated on either the German Wehrmacht’s breakthrough of the thin French defences on the River Meuse, on the evacuation of over 330 000 Allied troops from Dunkirk and the nearby beaches, or on the political level of an unravelling Anglo-French partnership. The continuing fight of the French armies, with some assistance from the British and others in the last month of operations ( c .25 May to 25 June), has been almost invisible, reduced to the status of an epilogue. This article re-examines questions of French command and control, force strength, and combat performance, focusing particularly on a series of case studies of French divisions that resisted the second-stage German offensive, Fall Rot (Case Red) from 5 June 1940. The evidence deployed offers a considerably more complex – and for the French, more creditable – picture of how resistance was reorganized after the shocks of May 1940. The German victory was not some kind of stroll in rural France, but came about only after very hard fighting that has been lost from sight in most evocations of the ‘fall of France’.

T he second phase of the western European campaign in 1940 – codenamed by the Germans ‘Case Red’ ( Fall Rot ) – has been neglected.

Most studies of the defeat of France focus overwhelmingly on the first three weeks – code-named ‘Case Yellow’ ( Fall Gelb ) – that commenced on 10 May 1940 and swiftly produced the Wehrmacht’s panzer breakthrough from Sedan and Monthermé to the Channel coast. But can we satisfactorily understand the events of 1940, and why they occurred, if the combats in late May and June continue to be dismissed as ‘a brief afterword’?

1

At the time of the fiftieth anniversary Eliot Cohen and

1

K.H. Frieser (with J.T. Greenwood), The Blitzkrieg Legend: The 1940 Campaign in the West

(Annapolis, MD, 2005), p. xiii; this first appeared as Blitzkriege-Legende: der Westfeldzug 1940

(Munich, 1995) and as Le Mythe de la guerre-éclair: la campagne de l’ouest, 1940 (Paris, 2003).

The work rests on extensive research from the German side and has exemplary maps.

War in History 2007 14 (2) 219–264 10.1177/0968344507075873 © 2007 SAGE Publications

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 220

220 Martin S. Alexander

John Gooch reaffirmed that France’s military performance was a ‘catastrophic failure’, without ‘even the smallest redeeming feature’.

2 This article challenges that judgement and the widespread dismissal of the significance of operations after Dunkirk and the elimination of the Allied forces north of the panzer ‘corridor’.

Although Case Red ended with German victory over France, an armistice taking effect on 25 June, the Germans did not have things all their own way. Indeed Case Red unfolded far less smoothly than Yellow. The

French army and its morale rallied impressively after the May disasters on the Meuse, in Belgium and in the Netherlands. French units fought tooth and claw in early–mid-June, as a recent book by Julian Jackson that presents events through a set of scenes and tableaux acknowledges.

3

Contrary to what Alistair Horne once affirmed, it was not simply a case of the Wehrmacht now being ‘free to mop up the French Army’ or that after Dunkirk ‘it became largely a matter of marching for the Germans’.

4

The contingency of the campaign in the west – and the innate frailties of the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe for extended war after late May 1940

– is not firmly grasped if the first fortnight of Germany’s Westfeldzug alone is examined.

Reconsideration of the familiar often occurs by means of a fresh perspective or a modified periodization. Both feature in this article. The dominant literature has it that operations were ‘over bar the shouting’ once Dunkirk was evacuated. For the Allies, in this reading, even if full time in the match had not been reached, the ‘scoreline’ of Wehrmacht successes – entire countries (the Netherlands, Belgium) forced to retire from the field – meant the game was up by 3 June at the latest.

5 Most literature on the French armies is limited to what its authors – Horne,

Claude Gounelle, Jeffery A. Gunsburg, Robert A. Doughty, Florian K.

Rothbrust, Jean Vanwelkenhuyzen, and Karl-Heinz Frieser – argue were the critical few days (12–16 May) on and just west of the River Meuse.

6

These works place overwhelming emphasis on Sedan and its aftermath,

3

4

2

5

6

E.A. Cohen and J. Gooch, Military Misfortunes. The Anatomy of Failure in War (New York,

1990, 1991), ch. 8, pp. 197–230: ‘Catastrophic Failure: The French Army and Air Force,

May–June 1940’ (quotation p. 220).

J. Jackson, The Fall of France: The Nazi Invasion of 1940 (Oxford, 2003), pp. 178–80.

A. Horne, ‘France, Fall of’, in I.C.B. Dear, ed., The Oxford Companion to the Second World

War (Oxford, 1995), pp. 408–14 (quotation p. 414).

This assumption colours R.E. Powaski’s Lightning War: Blitzkrieg in the West, 1940

(London, 2003); it also shapes the better-documented study by J.A. Gunsburg, Divided and Conquered: The French High Command and the Defeat of the West, 1940 (Westport, CT,

1979). Frieser’s Blitzkrieg Legend gives the three weeks after 31 May just three pages

(315–17), a perfunctory section subtitled: ‘Plan Red – Only an Epilogue’.

A. Horne, To Lose a Battle: France 1940 (London, 1969); C. Gounelle, Sedan, mai 1940

(Paris, 1965, repr. 1980); Gunsburg, Divided and Conquered ; R.A. Doughty, The Breaking

Point: Sedan and the Fall of France, 1940 (Hamden, CT, 1990); F.K. Rothbrust, Guderian’s

XIXth Panzer Corps and the Battle of France: Breakthrough in the Ardennes, May 1940 (New

York, 1990); J. Vanwelkenhuyzen, 1940: pleins feux sur un désastre (Brussels, 1997);

Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , esp. pp. 100–239; G. Chapman, Why France Collapsed (London,

1968); J. Williams, The Ides of May: The Defeat of France, May–June 1940 (London, 1968);

J.C. Cairns, ‘Some Recent Historians and the “Strange Defeat” of 1940’, Journal of

Modern History XLVI (1974), pp. 60–85.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 221

After Dunkirk 221 revealing that the Germans shared French surprise at the ease and speed of their breakthrough. Case Red operations after 4 June are mentioned only cursorily or not at all.

7 Other writers, chiefly British ones operating within a national historical discourse about Britain’s supposed ‘finest hour’, have understandably dwelt on the retreat to the Channel, the fight for Calais, and the rescue of 338 000 troops from Dunkirk.

8 The fierce and far more effective resistance offered in

June 1940 on the Somme, Aisne, and Moselle, on the Seine and Loire, has been left to a few non-academic writers and to local or regimental historians.

9

Yet even writers convinced that a decision in the west had been reached by the end of May, leaving no French lifeline to survival, perhaps owe us an explanation of why fighting continued and why French resistance was now more resolute than hitherto. For the French did not lay down their arms a day or two after Belgium did so (28 May).

Nor did they do so after the last evacuations at Dunkirk. On the contrary, the French armies made a Herculean effort to prepare for a new and more effective fight for France. The German staffs had to craft fresh plans to overcome a fast-reviving spirit. And the German troops met considerably more skilled military resistance. During June this resistance caused the Germans serious losses of soldiers, tanks, vehicles, and aircraft – but at a price to the French armies of only 27% of the

7

8

9

Frieser’s core argument is summarized in his chapter ‘La Légende de la blitzkrieg’, in

M. Vaïsse, ed., Mai–Juin 1940: défaite française, victoire allemande, sous l’œil des historiens

étrangers (Paris, 2000), pp. 75–86.

See M. Smith, Britain and 1940: History, Myth and Popular Memory (London and New

York, 2000); D. Reynolds, ‘Churchill and the British “Decision” to Fight on in 1940:

Right Policy, Wrong Reason’, in R.T.B. Langhorne, ed., Diplomacy and Intelligence during the Second World War: Essays in Honour of F.H. Hinsley (Cambridge, 1985), pp. 147–67.

A good short account of the evacuation is B.I. Gudmundsson, ‘Dunkirk’, Military History

Quarterly IX (1997), pp. 61–70. The controversies surrounding the evacuation are dissected in J. Vanwelkenhuyzen, Miracle à Dunkerque: la fin d’un mythe (Brussels, 1994).

See also Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 291–314; W.J.R. Gardner, ed., The Evacuation from

Dunkirk: Operation Dynamo, 26 May–4 June 1940 (London, 2000); R. Atkin, Pillar of Fire:

Dunkirk, 1940 (London, 1990); B. Bond, Britain, France and Belgium, 1939–1940

(London, 1990). Cf. Gen. J.-A. Doumenc, Dunkerque et la campagne de Flandre (Paris,

1947); Gen. J. Armengaud, Le Drame de Dunkerque (mai–juin 1940) (Paris, 1948); P. Le

Goyet and J. Foussereau, Calais 1940: la corde au cou (Paris, 1975); A. Neave, The Flames of Calais: A Soldier’s Battle, 1940 (London, 1972).

P. Nivet, ‘Les Soldats français sur la Somme (mai–juin 1940)’, in P. Nivet, ed., La Bataille en Picardie: combattre de l’antiquité au XXe siècle. Actes des colloques d’Amiens (16 mai 1998 et

29 mai 1999) (Amiens, 2000), pp. 221–38; P. Vasselle, La Bataille au sud d’Amiens

(Montdidier, 1948); idem, Les Combats de 1940, 18 mai – 9 juin: Haut-Somme et Santerre.

Ligne de l’Avre et de l’Ailette; VIIe Armée Frère, 1er et 24e Corps (Montdidier, 1970); idem,

Juin 1940 sur la Basse-Somme: Xe Armée Altmayer, 9e Corps d’armée, 13e DI, 5e DIC, 40e DI

(Montdidier, c .1973); R. Dietrich, ‘Le 24e RTS [Régiment de Tirailleurs Sénégalais] à la bataille de la Somme 1940’, in 24e RIMa: portes ouvertes, 25–26 juin 1988 (Perpignan,

1988); R. Macnab, For Honour Alone: The Cadets of Saumur in the Defence of the Cavalry

School, France, June 1940 (London, 1988). I am grateful to Dr William Philpott, Dept of

War Studies, King’s College, London, for the first four of these references and to

Randal Gray, formerly of Frank Cass Ltd, for the fifth. For an overview: Col. J. Vernet,

‘La Bataille de la Somme’, in C. Levisse-Touzé, ed., La Campagne de 1940: actes du colloque, 16 au 18 novembre 2000 (Paris, 2001), pp. 198–209.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 222

222 Martin S. Alexander deaths sustained in May (24 000 dead from 4–25 June as against 92 000 in the fortnight of 10–25 May).

Much evidence, then, stands against reading French defeat in 1940 as somehow predetermined – or even as an inevitably easy German triumph. In early June the Dunkirk evacuation was completed and both adversaries drew breath and paused. They now faced a second, different and considerably harder, phase of operations that would be known as the battle of France (see Figure 1). In this phase the key roles would be taken far less by the German panzer spearheads and the French B-series reservist divisions, but instead by the commonly overlooked bulk of the opposing armies – the infantry divisions and the artillery.

I. Fighting for France: Fresh Forces and

(Some) Fresh Ideas

By Dunkirk some friendly powers, to be sure, had fallen by the wayside – the Netherlands capitulated on 18 May and Belgium 10 days later.

10

However, new British formations were dispatched to aid France’s fight for survival by Winston Churchill, prime minister as well as minister of defence after 10 May, a more pugnacious and francophile individual than his predecessor, Neville Chamberlain.

11 Besides engineers there were lines-of-communication troops of General Lord Gort’s British

Expeditionary Force (BEF) in the lower Somme, Normandy, and

Brittany who had avoided the defeat in Belgium and the Nord.

12 The main surviving combat force from the original 10 BEF infantry divisions

10

11

12

See A. Ausems, ‘The Netherlands Military Intelligence Summaries, 1939–40, and the

Defeat in the Blitzkrieg of May 1940’, Military Affairs L (1986), pp. 190–199; idem, ‘Ten

Days in May 1940: The Netherlands Defense against “Fall Gelb”’, master’s thesis, San

Diego State University, 1983; D.J. Mol, ‘Feeding the Crocodile: The End of Dutch

Neutrality. Lessons in Intelligence and Small State Security from 1939–1940’,

MSc(Econ) diss., University of Wales Aberystwyth, 2002.

Cf. the view that from Churchill’s notorious 16 May visit to Gamelin and Reynaud in

Paris onwards the British leaders were accepting French defeat rather than trying to prevent it, and focusing on salvaging assets to help Britain fight on. See P.M.H. Bell,

‘Les Britanniques considéraient-ils la défaite française comme irrémédiable?’, in Vaïsse, ed., Mai–Juin 1940 , pp. 126–44; also P.M.H. Bell, France and Britain, 1900–1940: Entente and Estrangement (Harlow, 1996), pp. 232–50.

The British army was expanding to 55 divisions, as agreed in the winter of 1939–40 (an enlargement from earlier plans announced in spring 1939 for a 32-division army based on doubling the Territorial Army and reintroducing conscription). See D. French,

Raising Churchill’s Army: The British Army and the War against Germany, 1919–1945

(Oxford, 2000), pp. 157–59; M.S. Alexander, ‘“Fighting to the Last Frenchman”?

Reflections on the BEF Deployment to France and Strains in the Anglo-French

Alliance, 1939–40’, in J. Blatt, ed., The French Defeat of 1940: Reassessments (Providence and Oxford, 1998), pp. 296–326; B. Bond, British Military Policy between the Wars (Oxford,

1980), pp. 298–311; P. Dennis, Decision by Default: Peacetime Conscription and British

Defence, 1919–1939 (London, 1972), pp. 191–225; idem, The Territorial Army, 1907–1940

(Woodbridge, 1987), pp. 232–61; R.J. Minney, The Private Papers of Hore-Belisha (London,

1960), pp. 171–206; M. Glover, The Fight for the Channel Ports: Calais to Brest 1940, A Study in Confusion (London, 1985).

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 223

After Dunkirk 223

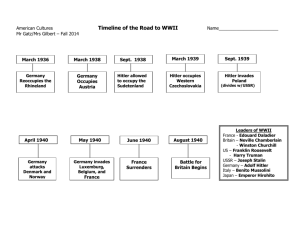

Figure 1 The battle of France

Source : Général Maxime Weygard, Mémoires , tome 3 (Paris, 1957). Map

© Editions Flammarion, Paris, whose permission for reproduction is hereby gratefully acknowledged.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 224

224 Martin S. Alexander was Major-General Victor Fortune’s 51st Highland Division.

13

This was supplemented by Major-General Roger Evans’s incomplete 1st Armoured

Division, assembling in Normandy in mid-May.

14

Two more British infantry divisions and a Canadian division, arriving through Cherbourg and

St Malo, supported the French 10th Army (General Robert Altmayer) west of Rouen in mid-June.

15

British units – if now few in number – were respected by the Germans for their ‘very high quality’ and were buttressed by two Polish divisions and a Polish tank brigade under General

Wladislaw Sikorski’s government in exile, a division of Czechs, and two new French corps headquarters with their staffs, artillery, engineers, and signals troops.

16

More significantly, the French had the defender’s advantage – seeking only to hold what they held. France’s intrinsic defensive doctrine stemmed from many factors, some political, others embedded in military thinking and conclusions drawn from operations in 1914–18.

First, satisfied by Versailles’s territorial terms in 1919 if not by the fragility of constraints on German rearmament, French voters and parliamentarians would not have financed an army had it trained in the

1920s and 1930s for revanchist offensives. Second, the defensive mindedness was buttressed and given literally concrete shape by the construction of the powerful fortified zones bordering the Saarland and

Baden-Wurtemburg after 1929 that became known as the Maginot Line.

Next, French war plans and military training followed from the sharp drop in available military manpower for France, 20 years after the fall in birth rate during 1914–18, so that the period from 1935 to 1939 was dubbed ‘the hollow years’ ( les années creuses ). Finally, like any organization cutting its coat according to its cloth, the French army regarded defensive combat, under firm top-down command, as most suited to its

13

14

15

16

On 10 May 1940 the Scotsmen were in Lorraine, each BEF division rotating there to gain acquaintance with French troops and a gentle baptism of fire. They became prisoners of Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division at St-Valéry-en-Caux on 12 June 1940. See

S. David, Churchill’s Sacrifice of the Highland Division, France 1940 (London, 1994);

B. Innes, St Valéry: The Impossible Odds (Edinburgh, 2004). On the ‘quiet’ Lorraine front in the Phoney War, see J.-P. Sartre (mobilized as a 34-year-old reservist in 1939), The War

Diaries of Jean-Paul Sartre, November 1939 – March 1940 , trans. Q. Hoare (London, 1984);

R. Felsenhardt, 1939–40 avec le 18e Corps d’armée (Paris, 1973), pp. 19–104.

Service historique de I’armée de terre (French Army Archives, at Vincennes: hereafter

SHAT), SHAT 7N2817: le général Albert Lelong (attaché militaire à Londres) à l’Etat-

Major de l’Armée (2e Bureau), no. 592/S, 5 October 1939.

Major-General Roger Evans, ‘The 1st Armoured Division in France, May–June 1940’

(privately produced, author’s collection); SHAT 32N476-81 (2nd DLC);

Vanwelkenhuyzen, Pleins feux , pp. 256, 285–86, 353–60; A. Danchev and D. Todman, eds., Field Marshal Lord Alanbrooke: War Diaries, 1939–1945 (London, 2001), pp. 73–88;

General Sir D. Fraser, Alanbrooke (London, 1983), pp. 160–71; General Sir J.H. Marshall-

Cornwall, Wars and Rumours of Wars: A Memoir (London, 1984), pp. 138–65; B. Karslake,

1940, The Last Act: The Story of British Forces in France after Dunkirk (London, 1979).

K.A. Maier, H. Rohde and B. Stegemann, Germany and the Second World War , trans. D.S.

McMurray and E. Osers, vol. 2 (Oxford, 1991), p. 234; J.-L. Crémieux-Brilhac, Les

Français de l’an 40 , 2 vols (Paris, 1990), vol. 2: Ouvriers et soldats , p. 644; SHAT 32N501-3

(war diaries of the Polish and Czech units).

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 225

After Dunkirk 225 short-service conscripts who did only 18 months with the colours from

1923 to 1928 and just 12 months from 1928 to 1936.

17

Also, a cautious recovery of faith that defensive battle could be staged with success began to flow through the French divisions rushing up and erecting strong points along the Somme, the St Quentin and Crozat canals, and the Aisne from 19 May onwards. Morale and confidence were recovering now that the disorderly retreats of mid-May were over.

The surviving armies were falling back onto shorter lines of communication, with easier access to tank repair shops, supply dumps, stores, and stockpiles. Most significantly, between 25 May and 5 June, the French army was gaining reinforcements with every passing day. One source of these was the initiative taken in November 1939 by General Maurice

Gamelin, the French commander-in-chief dismissed by Prime Minister

Paul Reynaud on 20 May, to expand the army through a ‘five month plan’. The scheme had generated three new infantry divisions, two additional ‘light’ divisions, a new colonial division, and three new North

African infantry divisions by the end of May 1940.

18

In addition there were 14 new ‘light’ infantry divisions, the divisions légères d’infanterie , in the process of establishment, 6 of them formed by

31 May, as well as the equivalent of 13 divisions of specialist fortress garrison units in the Maginot Line. Finally, around a quarter of the 112 000 or more French troops evacuated at Dunkirk fought again, once repatriated through the ports of Normandy and Brittany – notably General

Henri Vernillat’s 43rd Infantry Division, originally part of General

Henri Giraud’s 7th Army sent to the Netherlands and Belgium, around

Caen and Lisieux from 8 to 17 June.

19 Taken together, these formations were imperfect but significant substitutes for the 25 French divisions lost by the end of May.

20

Nor were all the new forces simply infantry, for the French refitted their armoured divisions quickly and made good the attrition sustained

17

18

19

20

These issues have generated an extensive literature. See, notably, R.A. Doughty, The Seeds of

Disaster: The Development of French Army Doctrine, 1919–1939 (Hamden, CT, 1985); Doughty,

Breaking Point , pp. 8–18, 27–30; E.C. Kiesling, Arming against Hitler: France and the Limits of

Military Planning (Lawrence, KS, 1996), esp. pp. 63–112, 136–39, 174–75; H. Dutailly,

Les Problèmes de l’armée de terre française, 1919–1939 (Paris, 1980), esp. pp. 39–41, 140–42,

176–87, 191–99, 202–204, 207–41; R.J. Young, ‘ La Guerre de Longue Durée : Some Reflections on French Strategy and Diplomacy in the 1930s’, in A. Preston, ed., General Staffs and

Diplomacy before the Second World War (Totowa, NJ, and London, 1978), pp. 41–64;

M.S. Alexander, ‘In Defence of the Maginot Line: Security Policy, Domestic Politics and the Economic Depression in France’, in R. Boyce, ed., French Foreign and Defence Policy,

1918–19: The Decline and Fall of a Great Power (London, 1998), pp. 164–94.

SHAT 1K224/7, dossier [hereafter, Dr.] titled ‘Le problème des effectifs’; ‘Grandes Unités nouvelles prévues au Programme des 5 Mois’, 15 February 1940; cf. SHAT 1N43, Gen.

Louis Colson (GOC interior depots and training camps): ‘Modifications prévues ou possibles progressivement dans l’organisation de l’Armée active à partir d’Octobre 1940’.

R. Looseley, ‘“Le Paradis après l’Enfer”: The French Soldiers Evacuated from Dunkirk in 1940’, MA diss., University of Reading, 2005; T. Richard, ‘La 43e Division d’Infanterie en Basse-Normandie: l’impossible renaissance, 4–26 juin 1940’, Revue Historique des

Armées CCXIX (2000), pp. 43–52; Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 246–51.

Cf. Vanwelkenhuyzen, Pleins feux , pp. 397–98, that these troops’ weaknesses made the remainder of the campaign merely ‘the management of inevitable defeat’.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 226

226 Martin S. Alexander in the first fortnight of operations. Both the 1st and 2nd DCRs ( divisions cuirassées de réserve , heavy armoured divisions) gained new and more talented commanders, General Marie-Joseph Welvert and Colonel Jean

Perré respectively, while their destroyed or abandoned tanks were swiftly replaced after 20 May.

21 Meanwhile the armoured force was strengthened by the deployment of the newly formed 4th DCR under Colonel

(later Brigadier-General) Charles de Gaulle. In a series of counterstrokes at Montcornet, Crécy-sur-Serre and Laon between 15 and 20

May, de Gaulle startled the Germans, trapping the XIX Panzer Corps commander, General Heinz Guderian, for some ‘uncomfortable hours’ in Holnon Wood.

22 But de Gaulle was less successful when he assaulted the German infantry and anti-tank bridgehead on the Somme’s south bank at Abbeville between 28 and 30 May, when many of the 4th DCR’s tanks were knocked out. Better results attended the more methodically prepared attacks of Perré’s 2nd DCR on 3 and 4 June.

23

When the Case Red offensive commenced at dawn on 5 June, 2nd

DCR had regrouped 25 km behind the River Bresle, south of the Somme.

Meanwhile 4th DCR was reassembling around Marseille-en-Beauvaisis. It had just received new tanks to make good its losses sustained at Abbeville and, with de Gaulle summoned to the side of the prime minister, Paul

Reynaud, and appointed to the government as under-secretary for war on

5 June, received a new commander, General de La Font, two days later.

24

French armour had been re-equipped with impressive speed by the first week of June 1940. Despite the damage sustained in May the spirits of the battalions in the arme blindée were high, and the tank crews fought with great heart and competence in the latter stages of the French campaign.

21

22

23

24

1st DCR lost 158 of its 174 tanks in a stern fight against 5th Panzer Division (von Hartlieb) and part of 7th Panzer Division (Rommel) at Anthée–Flavion–Florennes on 15 May, and then against 7th Panzer Division at Avesnes on 16 May (though more ran out of fuel and were abandoned than were knocked out by German fire). See SHAT 32N447: 1st DCR war diary; G. Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindée française , tome 1, Mai–Juin 1940: les blindés français dans la tourmente (Paris, 1998), pp. 101–103, 180–85; D. Lehmann, ‘The Battle of

Flavion in Belgium (15th May 1940): The French 1st DCR against the German 5.PzD and

7.PzD’, at www.militaryphotos.net/forums/archive/index.php/t-43180.html (accessed

14 July 2006); Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 236–39, 267–71; Crémieux-Brilhac, Français, vol. 2, pp. 596–97, 617; Vanwelkenhuyzen, Pleins feux , pp. 109–11. First-hand published accounts in M.-A. Fabre, Avec les héros de ‘40’ (Paris, 1946), p. 104; B.H. Liddell Hart, ed.,

The Rommel Papers (London, 1953), pp. 21–28.

P. Huard, Le Colonel de Gaulle et ses blindés: Laon, 15–20 mai 1940 (Paris, 1980);

J. Lacouture, De Gaulle: The Rebel (1890–1944) (London, 1990), pp. 180–83; Saint-

Martin, L’Arme blindée française , pp. 214–30; H. Guderian, Panzer Leader , trans.

C. Fitzgibbon (London, [1952] 1974), p. 111.

SHAT 32N461-9 (2nd DCR archives). H. de Wailly, De Gaulle sous la casque: Abbeville 1940

(Paris, 1990), is critical of de Gaulle’s plan, dispositions and stubbornness at Abbeville.

A commander of one of de Gaulle’s regiments equipped with Somua S35 tanks stated:

‘The equipment was very good; [but] our men’s lack of training with it prevented our obtaining satisfactory results’, adding that ‘The absence of communications sets rendered the regiment un-commandable [ incommandable ]’. Archives nationales de

France, Paris [hereafter AN], AN 496 (Daladier papers) 4DA7/Dr.3/sdr.c: ‘Témoignages sur le valeur de nos chars: 4e DCR: rapport du Colonel François, commandant le 3e

Régiment de Cuirassiers’; cf. Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindée française , pp. 178–79, 231–53.

Lacouture, De Gaulle , pp. 184–87, 189–207; Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindée française , p. 254.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 227

After Dunkirk 227

In the wider picture, too, not only were the formations available to

General Maxime Weygand, Gamelin’s successor as generalissimo, well armed, their morale was good. The attitude of French soldiers was markedly more combative from about 22 May onwards. Several reasons account for this upturn. One was that the divisions deploying to the

Aisne and Somme knew of German successes only by hearsay. A second was the growing confidence of French troops in their weapons, most of which were outperforming the Wehrmacht’s. The ‘resistance of the heavy French and British tanks to German shot, while at the same time they scored kills with their own guns, vindicated tanks that were both heavily armoured and well armed – particularly if they could be thrown into massed action’ (as occurred in a couple of isolated instances).

25 A third was that surviving battle-tried troops – such as the officers and men of the 1st, 2nd, and 4th DCRs, and the 23rd, 29th, 43rd, and 47th infantry divisions – had learnt crucial tactical lessons.

26 The French artillery in particular, as the Wehrmacht acknowledged, proved technically superior to its counterpart. This ‘redoubtable weapon’, as Jean-

Louis Crémieux-Brilhac has termed it, was put to telling use by gunnery officers whose ‘rapid adaptability’ to new tactics, such as deploying

75 mm field guns in an anti-tank role, was ‘remarkable’.

27

In terms of the infantry, though excellent divisions had been lost in the north, so had others of indifferent quality. About a third of the formations had been undermined by their incomplete provision with modern equipment and by their fragile morale. The weakest were the B-series reservist divisions of General André Corap’s 9th Army, formations that comprised the second echelon reserve generated by general mobilization. Each of the 20 peacetime ‘active’ infantry divisions in metropolitan

France shed half their regular officers and NCOs on the publication of the mobilization decree. These men formed the command cadres of two

‘spin-off’ formations, the A-series and B-series divisions, whose constitution tripled the size of the army. The A-series units gained most of these

‘cast-off’ professional officers and NCOs, while the B-series type received only 10%. In the latter divisions, as a result, even officers as senior as battalion commanders were often reservists.

28

25

26

27

28

K. Macksey, The Guinness Book of Tank Facts and Figures (Enfield, 1972), pp. 107–108.

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol.2, pp. 640–43; earlier, Gamelin had opined to his personal staff that ‘The crux of things is that troops like ours, not yet battle-hardened, should be able to withstand an all-out German onslaught.’ SHAT 1K224/9: Cabinet

Gamelin – Journal de marche, 14 October 1939.

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, p. 644; e.g. the order from the 23rd Infantry Division commander, Gen. Jeannel, on 28 May: ‘Remember that all 75 mm artillery must be placed in situations to intervene in an anti-tank defence role even if, for that, it must abandon its direct fire-support missions’, in SHAT 32N134: 23e Div. d’Infanterie (Etat-

Major: 3e Bureau), no. 1073 S/3: ‘Ordre général d’opérations’, 28 May 1940, p. 15.

AN 496 (Daladier papers), 4DA1/Dr.4/sdr.a: Etat-major de l’Armée paper M14, ‘Le Problème militaire français’, 1 June 1936: Annexe-Note no. 1; The National Archives/Public Record

Office, Kew, London [hereafter TNA/PRO], FO 371, 19870, Col. Bernard Paget, MI3a (War

Office Directorate of Intelligence): ‘General Note on French Army Strengths, Service and

Mobilization Arrangements’, 10 December 1935, pp. 2–4, 6; Dutailly, Problèmes , pp. 264–68; also F. Cochet, Les Soldats de la drôle de guerre, septembre 1939 – mai 1940 (Paris, 2004).

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 228

228 Martin S. Alexander

The B-series reservists were older men who had served as conscripts in the 1920s. Lacking martial spirit, their esprit de corps was weak, their morale brittle. A short annual summer exercise had been the limit of their more recent encounters with army life, and many among them struggled with the wirelesses, new weapons, and even motor vehicles they received in 1939–40.

29 In General Charles Huntziger’s 2nd Army on the Meuse at Sedan on 10 May were the 55th Infantry Division of

General Henri Lafontaine (disbanded in the First World War and only recently re-formed) and 71st Infantry Division of General Joseph Baudet.

Both were B-series divisions and have unjustly become synonymous with the entire French army of 1940.

30 Smashed by XIX Panzer Corps, their fate, and the destruction of several A-series divisions too, was part of the tragedy of May 1940 that bore little comparison to the far stiffer contest that unfolded when battle resumed against France’s remaining active and reservist formations from 5 June. Making for Tours the following week, the New Yorker ’s correspondent, A.J. Liebling, ‘soon met soldiers moving north to Paris as everybody else moved south. They seemed content with what they were doing. There were infantrymen in camions and motorcyclists on their machines, and their faces were strong and untroubled.’ 31

More damaging for the intended defence on the Somme and Aisne was the loss in Belgium and the southern Netherlands of the three

‘active’ series motorized infantry divisions and one armoured cavalry

DLM (light mechanized division) in Giraud’s 7th Army. These formations had paid the price of the ill-advised ‘Breda dash’, imposed by

Gamelin in a hazardous bid to link the Dutch army into Allied dispositions.

32 To 7th Army’s right was the BEF (less 51st Highland Division) and on its right, in central Belgium, General Georges Blanchard’s 1st

Army. This contained France’s other two DLM armoured cavalry divisions, forming General Jules Prioux’s mechanized corps, and three more motorized infantry divisions, 1st Moroccan Division and two North

African infantry divisions.

33

29

30

31

32

33

Dutailly, Problèmes, pp. 140–46; J. Vidalenc, ‘Les Divisions de série “B” dans l’armée française dans la campagne de France’, Revue Historique des Armées , IV (1980), pp. 106–26; Kiesling, Arming against Hitler , pp. 63–71, 86–106; Crémieux-Brilhac,

Français , vol. 2, pp. 502–506, 522–24.

On 55th and 71st Inf. Divs. at Sedan see Jackson, Fall of France , pp. 167–73; Doughty,

Breaking Point , pp. 102–106, 108–20, 197–200; Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 145–53;

Vanwelkenhuyzen, Pleins feux , pp. 59–64; Gen. C. Grandsard, Le 10e Corps d’armée dans la bataille, 1939–1940 (Paris, 1949); Col. P. Guinard, J.-C. Devos and J. Nicot for Ministère de la Défense, Etat-Major de l’Armée de Terre: Service Historique, Inventaire sommaire des archives de la guerre (série N, 1872–1919): introduction. Organisation de l’armée française.

Guide des sources. Bibliographie (Troyes, 1975), pp. 101, 103.

A.J. Liebling, The Road Back to Paris (New York, 1988), p. 94.

TNA/PRO, FO 371/32082, ‘Rapport Giraud: Les causes de la défaite; 26 July 1940;

B. Chaix, En mai 1940 fallait-il entrer en Belgique? Décisions stratégiques et plans opérationnels de la campagne de France (Paris, 2000); Col. R. Villatte, ‘L’Entrée des français en Belgique et en Hollande en mai 1940’, in [no author] La Campagne de France (mai–juin 1940) (Paris,

1953), pp. 60–76; M. Lerecouvreux, L’Armée Giraud en Hollande, 1939–1940 (Paris, 1951).

Gen. J. Prioux, Souvenirs de guerre, 1939–1943 (Paris, 1947), pp. 55–136.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 229

After Dunkirk 229

Much has correctly been made by writers of the significance of losing these forces in the north. Under the more limited defensive advance to the Scheldt (Escaut), the Franco-British plan of September–November

1939, 7th Army had been in general reserve near Reims. Had 7th Army remained in Champagne, there would have been a much better prospect of stopping the German push westwards from the Meuse in mid-May.

34

The Breda manoeuvre remains the fateful ‘gamble gone wrong’ of 1940, forever staining Gamelin’s record as a wartime commander-in-chief.

35

But despite these losses, 60 French divisions and 4 British remained to fight for France, along the line of the Somme–Oise–Ailette–Aisne.

Many of these formations had already begun by 20 May to transfer here, on Gamelin’s orders, from Alsace-Lorraine, the Jura, and the

Alps. Weygand accelerated the switch the moment he assumed command.

36 These divisions were fresh, well armed, and well supplied, with high morale, and they arrived rapidly, the French 4e Bureau exploiting interior lines of communication. In the crisis when the German armies approached Paris in 1914 a ‘secret weapon’ had been available to General Joseph Joffre, then the French commander-in-chief. This was

France’s highly efficient railway network, able to ‘move an entire corps from his right to his left in five or six days’.

37 The advantage remained in 1940, with civilian motor vehicles supplementing trains and military convoys. ‘The buses have disappeared’, recorded Alexander Werth,

Paris correspondent of the Manchester Guardian , on 16 May. This had startled French people: ‘Reminded them of the Battle of the Marne.

Many taxis have also disappeared, perhaps for the same reason.’ 38

Advance parties from the redeployed formations arrived on the

Somme with impressive speed. Mobile elements from the reconnaissance battalion of General Joseph Jeannel’s 23rd Infantry Division reached the river at Ham on 17 May. They immediately set up defensive positions, strengthened by the arrival with refugees from the north of a

Renault R35 tank and some 75 mm field artillery. At noon the next day the first German motorcycle detachments appeared and were repelled as infantry stragglers reported the Panzers heading northwest for the

34

35

36

37

38

Chaix, Fallait-il entrer en Belgique?

, pp. 95–199 and maps at pp. 317–28; cf. D.W. Alexander,

‘Repercussions of the Breda Variant’, French Historical Studies VIII (1974), pp. 459–88.

P. Le Goyet, Le Mystère Gamelin (Paris, 1976), pp. 292–350 (terming the days 10–20 May

‘Gamelin’s “real war”’); Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 90–93.

B. Destremau, Weygand (Paris, 1989), pp. 403–404. Weygand was a true generalissimo, with command authority over the chiefs of the French air force and navy – a remit beyond that previously enjoyed by Gamelin, who had been only commander-in-chief of all land forces.

R.A. Doughty, Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War

(Cambridge, MA, 2005), p. 99 (about 110 trains were required to move a twodivision corps); see also SHAT 34N1017, Dr. 5: GQG (Grand Quartier général, supreme command) Direction des Mouvements et Transports sur Route: Memento de service des mouvements et transports de route (Paris, March 1940) – a 168-pp. handbook issued to all divisional staffs based on the war of movement of autumn 1918 and experiences since September 1939.

A. Werth, The Last Days of Paris (London, 1940), p. 45.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 230

230 Martin S. Alexander coast. Despite a Luftwaffe raid on the railway at Chaulnes, Weygand’s great switch of forces from the right to left flanks was easily and swiftly completed. Trains and bus fleets disgorged men, munitions, artillery, and stores at Rouen, Noyon, Soissons, and Chantilly on 19 and 20 May, including the main formations of General Fougère’s XXIV Corps (23rd

Infantry Division, 29th Alpine Division, and 3rd Light Infantry Division).

The rest of the now reconstituted 7th Army, under a forceful new commander, General Aubert Frère, along with Altmayer’s new 10th Army to its west, arrived between 23 and 28 May.

39

Unfortunately on 20 May the 10th Panzer Division from Guderian’s

XIX Panzer Corps reached Péronne and helped beat off French attempts to take it back. A similar situation had unfolded lower down the Somme at Amiens, Picquigny, and Abbeville. Many of the arriving

French infantry therefore became temporary navvies, lending their muscle to the army’s corps of engineers. These men, the Génie militaire , were racing against the clock as they toiled to erect new defensive positions.

40 The Somme’s hamlets and villages, along with those of Picardy and Champagne, became demolition sites, their streets and squares echoing to the clang of pickaxes and crash of controlled demolitions.

The work at Rethonvillers, 5 km northeast of Roye, was recorded in the diary of Captain Paul de Lussan, adjutant of 34th GRDI ( Groupe de reconnaissance de division d’infanterie ), the reconnaissance battalion of

29th Alpine Division, on 29 May: ‘A big village with many routes in and out […] It took the entire day to set up its defence, construct barricades etc.’ 41

As the bastions took shape throughout a zone stretching 8 km to the rear of the Somme and Aisne, the local inhabitants fled, their exodus swelling the stream of refugees from Belgium, the Nord, and the

Meuse.

42 In the now-empty houses, farms, and ubiquitous sugar-beet factories the troops knocked out windows, sandbagged doorways, and sited machine-guns, along with 25 mm and 47 mm calibre anti-tank artillery, in mutually supporting strong points. Meanwhile roadblocks were set, covered by machine-gun nests and by the 75 mm and 105 mm

39

40

41

42

Vasselle, Les Combats de 1940 , pp. 12–13, 14–19.

Destremau, Weygand , pp. 455–56; Dutailly, Problèmes , p. 199.

SHAT 34N527: 29th DI [ division d’infanterie , Infantry Division] Alpine: Capt. Paul d’Audibert de Lussan, Adjutant, 34th GRDI, Carnets de route.

G. Sadoul, Journal de guerre, 1939–40 (Paris, 1977), p. 227: 36 years old in 1940,

Sadoul was a Communist Party activist and already a distinguished film historian and critic. The novelist Arthur Koestler saw ‘The muddy cars of the refugees from the north – mattresses on top, bicycles on the running-board, bulging with exhausted people – crossing Paris like a swarm of birds on their flight from a hurricane’

( Scum of the Earth , London, 1941, pp. 155–56). See also R. Vinen, The Unfree French:

Life under the Occupation (London, 2006), pp. 28–43. In-depth scholarly treatments are J. Vidalenc, L’Exode de mai–juin 1940 (Paris, 1957); N. Dombrowski, ‘Beyond the Battlefield: The French Civilian Exodus of May–June 1940’, PhD thesis,

New York University, 1995. Cf. comparisons in J.S. Torrie, ‘For Their Own Good:

Civilian Evacuations in Germany and France, 1939–1945’, PhD thesis, Harvard

University, 2002.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 231

After Dunkirk 231 calibre divisional and corps artillery to the rear.

43

Weygand’s plan was to construct a new, deep, but aggressive defensive system along the

Somme and Aisne, to restore a war of position. The village redoubts acquired the nickname ‘Weygand hedgehogs’. They presented an attacker with an uninvitingly spiky 360 degree position – no easy prey – and were inspired by the elastic defence of 1917 and 1918 that had proven superior to linear positions in channelling a breakthrough and choking its momentum.

44

Behind these strong points were more newly arriving infantry divisions, as well as the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th DLCs (light cavalry divisions), which were half-mechanized, and 2nd DCR on the Bresle, west of

Hornoy and Molliens-Vidame, with Evans’s 1st (British) Armoured Division deploying behind the Andelle, northwest of Forges-les-Eaux.

45

It was all the more unfortunate, then, that the new defences and their well-motivated defenders were compromised by the German lodgements gained on the Somme’s south bank.

46

Because the lodgements presented excellent assault bridgeheads, the French launched renewed attempts to eliminate them, making attacks with composite battle groups of fresh troops. One group consisted of Lieutenant-Colonel René Landriau’s

34th GRDI (reconnaissance battalion of 29th Alpine Division, whose main body was still in transit from Lorraine), accompanied by Foreign

Legionnaires from 97th GRDI (reconnaissance battalion of General

Barre’s 7th North African Infantry Division).

47

This battle group attacked the German advance guards in Péronne’s southern suburbs on 20 May, also fighting a sharp action that day at Villers-Carbonnel to the southeast. Landriau’s force showed that the French army had rediscovered its fighting spirit. Its troops, a mix of active-duty and reservist personnel, ‘conducted themselves splendidly, their calmness under fire comparing well with their Legion comrades’. The 34th GRDI was praised in a divisional citation for ‘knowing how to organize itself, use its weapons coolly, and maintain its self-belief’.

48

43

44

45

46

47

48

SHAT 32N218: 42nd Inf. Div. Journal de marche et opérations [French unit war diary, hereafter: JMO] génie divisionnaire (on the Aisne); 30N242: XXIV Corps engineering

JMO (9 February–10 July 1940) and ‘Notes sur la main d’oeuvre, février – juillet 1940’;

30N243: XXIV Corps, ‘Notes sur les ponts de la Somme, points de passage, destructions’; 30N62: VIII Corps, 4e Bureau papers and JMOs for corps artillery and engineers; 30N75: IX Corps, JMO de l’EM [Etat-Major, Military Staff] de Génie

(September 1939–July 1940); 30N216: XVIII Corps, Génie: travaux et notes relatives à la

DCA [Défense contre avions].

B.I. Gudmundsson, ‘The Hedgehogs of Amiens’, Military History Quarterly IX (1997), p. 67; Vasselle, Combats de 1940 , pp. 30–31; Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindée française , pp. 158–61; F.O. Miksche, Blitzkrieg (London, 1941).

Commandant [Major] Pierre Lyet, La Bataille de France, mai–juin 1940 (Paris, 1947), pp. 120–21 (map).

Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 252–69, 274–78.

Vanwelkenhuyzen, Pleins feux , pp. 261–65, 284–89; SHAT 32N385: 7th DINA [ Division d’infanterie North-Africaine , North African Division] war diary (20 March–11 July 1940);

32N386–9 for the rest of this division’s surviving papers.

SHAT 34N527: 29th DI Alpine: Capt. de Lussan’s carnets de route, incorporating 29e

DI/EM: ‘Note de Service’ no. 40/1, 22 mai 1940.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 232

232 Martin S. Alexander

But on 22 May the Germans repositioned General von Wietersheim’s

XIV Motorized Corps to guard this sector as Guderian’s XIX Panzer

Corps moved north to Dunkirk. Over the succeeding days Wehrmacht infantry at last caught up and reached the Somme river and bridgeheads.

49 The lodgements withstood the French attacks and remained as breaches in the integrity of the Weygand Line. ‘Duroc [a press briefer] at the War Office’, Werth noted on 2 June, ‘tells me they’re worried about the three German bridgeheads: at Amiens, Péronne and Ham’. Large

German infantry concentrations had been detected in the Péronne region. ‘He thinks the Germans will try to push towards Rouen and towards Reims: leaving Paris isolated’.

50 This was an accurate forecast of

Case Red, as a pause now occurred in operations, the lull limiting air as well as ground operations.

51

II. Fighting for France: The Impact of

Air Operations and Intelligence Problems

The Luftwaffe had flown bombing sorties in close support of

Wehrmacht ground units in the fighting west of the Meuse from 12 to

16 May.

52 But taking the six-week campaign as a whole, these Luftwaffe missions occurred with diminishing frequency as German air power concentrated on fighting for aerial mastery. Air activity tailed off markedly as the Luftwaffe paused after Dunkirk to repair damaged aircraft and relocate squadrons to forward airfields now in German hands in Belgium and northern France. In June 1940 operations would be conducted deeper into France, and were characterized by extensive aerial combat, operations against French road and rail networks to hamper troop redeployments, and attacks on refugee columns. There were few instances in June of the Luftwaffe playing the ‘flying artillery’ role, for all that this has become entrenched as a major ‘explanation’ for German victory in 1940.

53

Even in Poland the Luftwaffe had suffered 29% losses (560 aircraft destroyed of a total of 1929 engaged). This was a loss-rate far higher than expected, and was followed by further attrition during the Norway campaign in April 1940.

54 From 10 May to 3 June, first over Belgium and

49

50

51

52

53

54

Vasselle, Combats de 1940 , pp. 27–29.

Werth, Last Days of Paris , p. 119.

E. R. Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant: The Rise and Rise of the Luftwaffe (London, 1999), p. 242, table 23: ‘Attacks on French Targets, 10 May–8 June 1940’.

Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 44–54, 342–45; Doughty, Breaking Point , pp. 132–37;

J.S. Corum, The Luftwaffe: Creating the Operational Air War, 1918–1940 (Lawrence, KS,

1997), p. 277. Cf. sights witnessed by German follow-up infantry in de Wailly, De Gaulle sous la casque , pp. 34–35.

See, for example, Corum, Luftwaffe , pp. 278–80.

Figures from tables in Maier et al., Germany , vol. 2, pp. 86–87, 101, 106, 117–18, 121,

124–25. For the 1 September 1939 Luftwaffe order of battle see Hooton, Phoenix

Triumphant , pp. 281–88; on the Luftwaffe in Poland, Corum, Luftwaffe, pp. 272–77.

Cf. K.A. Maier, ‘The Luftwaffe’, in P. Addison and J.A. Crang, eds, The Burning Blue:

A New History of the Battle of Britain (London, 2000), pp. 15–21.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 233

After Dunkirk 233 the Champagne-Ardennes and then above Calais and Dunkirk, the

Royal Air Force and French fighter squadrons put up a lively fight for the skies.

55 French pursuit and interceptor squadrons, particularly those operating the new Dewoitine 520, took a heavy toll of the Luftwaffe.

56

Though French army units did collapse under the combination of heavy Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe attacks on the Meuse, and in the infamous ‘panic’ at Bulson on 13 May, anti-aircraft defences in late May and into June improved.

57 French fighters more often challenged German aircraft once the Luftwaffe flew deeper into French air space.

58 General

François d’Astier de la Vigerie, commanding the ZOAN (Zone of Air

Operations: North), was right to emphasize that ‘the sky was not empty’ of French aircraft.

59 The armée de l’air and the Luftwaffe fought

‘a battle of attrition which took place increasingly behind enemy

[French] lines’.

60 In all the Luftwaffe lost 26% of its in-service strength as of 4 May, during the six-week campaign over France and Belgium.

61

The attrition included 521 bombers lost by 25 June (of 1758 in squadron service on 4 May 1940), a 30% rate of destruction – a rate also sustained by the Messerschmitt Me 110 twin-engined two-seater Zerstörer and by the

Junkers Ju 87 dive-bomber force.

62 The skies were fiercely contested. As the distinguished German air-power historian Horst Boog notes, before the Luftwaffe could commence air war against Britain it ‘had to recover from the heavy losses incurred during the French campaign’.

63

61

62

63

55

56

57

58

59

60

For this phase of air operations and losses see Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , pp. 257–62; also Anon. [Paul Richey], Fighter Pilot: A Personal Record of the Campaign in France,

September 8th 1939 to June 13th 1940 (London, 1941), pp. 85–119.

In an extensive literature see especially: P. Facon, L’Armée de l’air dans la tourmente: la bataille de France, 1939–1940 (Paris, 1997); Gen. C. Christienne, ‘L’Armée de l’air dans la bataille de France’, in Les Armées françaises pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale,

1939–1945: actes du colloque de Paris, mai 1985 (Paris, 1986); P. Martin, Invisibles vainqueurs: exploits et sacrifices de l’Armée de l’air en 1940 (Paris, 1990); J.A. Gunsburg,

‘L’Armée de l’Air vs. the Luftwaffe, 1940’, Defence Update International XLV (1984), pp. 44–53; P. Buffotot and J. Ogier, ‘L’Armée de l’air française dans la campagne de

France, 10 mai–25 juin 1940: essai de bilan numérique d’une bataille’, Revue Historique de l’Armée (1975), pp. 88–117; D. Griffin, ‘The Role of the French Air Force: The Battle of France, 1940’, Aerospace Historian (1974), pp. 144–53. Cf. A. Ausems, ‘The Luftwaffe’s

Airborne Losses in May 1940: An Interpretation’, Aerospace Historian (1985), pp. 84–88;

W. Murray, Luftwaffe (Baltimore, 1985), pp. 39–46; Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , pp. 239–71; Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 44–54.

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, pp. 563–65, 574–89.

See Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 157–61, 174–83; Jackson, Fall of France, pp. 163–67;

For another case of mass flight or surrender by troops shattered by concentrated airarmour attack in mid-May see J. Minart, P.C. Vincennes: secteur 4 , 2 vols (Paris, 1945), vol. 2, pp. 221–22.

Gen. F. d’Astier de la Vigerie, Le Ciel n’était pas vide (Paris, 1952); Crémieux-Brilhac,

Français , vol. 2, pp. 652–56, 665–67.

Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , p. 247; also M. Smith, ‘The RAF’, in Addison and Crang,

Burning Blue , pp. 22–36, esp. 31–36.

Figures from tables and bar charts in Murray, Luftwaffe , pp. 44–45.

Op. cit.

H. Boog, ‘The Luftwaffe’s Assault’, in Addison and Crang Burning Blue , pp. 39–54

(quote, p. 40). Boog corroborates Murray, Luftwaffe , pp. 48–49, and Crémieux-Brilhac,

Français , vol. 2, pp. 659, 666–69; Luftwaffe availability rates in Maier et al., Germany, vol. 2, pp. 252–53, 278–79.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 234

234 Martin S. Alexander

Air-force influence on ground operations diminished as May closed.

On 26 May soldiers of the French 13th Infantry Division encountered a lorry driver from Corap’s 9th Army as they moved into the new ‘Weygand

Line’ southwest of Amiens. The driver had survived his parent formation’s collapse on the Meuse and had since been shuttling soldiers up to the new front. ‘At first we got bombed’, he reported, ‘but things are going better now. Our fighter aircraft have got into action at last. As soon as they meet a spot of resistance, the Germans pull back.’ 64

On 31 May the French chief of air staff, General Joseph Vuillemin, centralized command of all remaining French aviation and attempted to disrupt transfers of German land forces southwards in readiness for

Case Red.

65 To this end the Allies flew 454 bomber sorties between

28 May and 4 June (66% of them by the armée de l’air ). German troop movements, however, proceeded even in daylight ‘without a hitch’, in the words of Albert Kesselring, a Luftwaffe general.

66 On the French side, too, the ground forces suffered little more than sporadic strafing as they transformed the Somme and Aisne villages into ‘hedgehogs’.

67

The duels in the sky were intense and almost constant, however, with the result that Luftwaffe serviceability to support Case Red on 5 June remained 30% down on the aircraft available on 10 May. Flying over

300 sorties a day on 5, 6, 7, and 8 June, these days were ‘the French fighter arm’s finest hours’.

68

‘Allied inferiority in the air’, as Douglas Porch correctly notes, ‘was not the decisive element in the campaign.’ 69 But the Luftwaffe did manage two significant and under-recognized achievements. First, it prevented Allied generals gathering much-needed tactical intelligence about German dispositions during their preparatory phase to the assault on the Weygand Line. Second, it restricted the refuelling operations and manoeuvre of French armour from which counterstrokes would be required if Weygand’s improved fighting tactics were to do more than delay the Wehrmacht.

On the first of these effects, the Luftwaffe helped shroud the

Wehrmacht’s stage-by-stage redeployments southward from Dunkirk in a fog of war. Signals intercepts rarely cut through the murk in these early months of the war, ‘Enigma’ decrypts being fragmentary and of short duration owing to German code changes.

70 Aerial reconnaissance might

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

Sadoul, Journal de guerre , p. 228, 26 May 1940; cf. Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , pp. 257–58.

Facon, L’Armée de l’air , pp. 220–27; Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, pp. 652–54, 657–58.

Quoted in Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , p. 262; cf. Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , p. 343.

SHAT 34N527, 29e DI Alpine (34e GRDI): Capt. de Lussan, Carnets de route, p. 12,

30–31 May, 2–3 June 1940.

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, pp. 665–66; cf. Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , pp. 262,

264–66; Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 309–10, 343.

D. Porch, ‘Why Did France Fall?’, Military History Quarterly II (1990), pp. 30–41

(quote, p. 39).

Cohen and Gooch, Military Misfortunes , pp. 223–24; M.S. Alexander, Republic in Danger:

General Maurice Gamelin and the Politics of French Defence, 1933–1940 (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 323–26, 334–36; R.A. Doughty, ‘The French Armed Forces, 1918–1940’, in A.R. Millett and W. Murray, eds, Military Effectiveness , 3 vols (London, 1988), vol. 2, pp. 39–69, esp. 50–52.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 235

After Dunkirk 235 have produced more intelligence, given the blue skies and superb visibility on most days in May and June 1940. However, the French air force had dropped priority for reconnaissance and army support after winning independence in 1933. Its surviving reconnaissance aircraft – BCR

( bombardement–combat–reconnaissance ) machines from 1932–34 – were few in number and obsolete. Missions deeper than 11 km behind

German lines had been prohibited in November 1939, and would have been suicidal in the intense fighting of May–June 1940. ‘When I asked for and obtained some reconnaissance flights’, noted the 2nd DCR’s commander, Colonel Perré, ‘my requests were conscientiously and courageously met, but there was never any depth to their incursions over enemy territory.’ 71 Bereft of information, French generals were left guessing how best to deploy their units as these arrived on the Somme,

Oise, and Aisne. ‘Personally’, wrote General Baudouin, the commander of 13th Infantry Division, ‘the absence of intelligence and firm orders from the high command caused me dreadful anguish’.

72

Nor was it easy to obtain enemy soldiers to interrogate. Jeannel’s 23rd

Infantry Division took 13 prisoners when its leading echelons clashed with German reconnaissance forces, reaching the 23rd’s newly allotted defensive sector along the St Quentin canal from Ham through Jussy to

Tergnier on 19 May. But the Germans swiftly took steps to minimize their risk from raids. Patrols from 23rd Division probed the north bank of the canal during the night of 21–22 May but returned emptyhanded, finding ‘that the enemy left only very weak elements in contact during the hours of darkness’.

73 Jeannel’s men had slightly more success a week later, several patrols crossing the canal on 29 May during the day and after dark to reconnoitre the enemy’s positions, one of the night raids pulling off a coup de main that yielded four prisoners.

74

Most of the French infantry, however, were required for working parties to construct Weygand’s ‘hedgehogs’ the moment they arrived on the Somme and Aisne. Few could be spared for raiding and, in consequence, most officers taking charge of the forward defensive sectors were reliant on what their outposts saw or heard. The rumble of heavy traffic behind the German front line was reported on 31 May and

1 June, on the routes départementales from Péronne southeast to Tertry, and from Péronne to Athies. Identifying the enemy’s type and strength became almost impossible, however, when the German artillery that had been peppering the forward positions of 29th Alpine Division demolished the Pargny and Voyennes church towers on 1 June – vantage points in which 29th Division had set up observers.

75

73

74

75

71

72

AN 496 (Daladier papers) 4/DA7/Dr.3: compte-rendu de la 2e Div. Cuirassée, p. 15;

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, p. 652.

SHAT 32N77, Dr. 2: ‘Extrait du Carnet de notes du général de division Baudouin, commandant la 13e DI’, p. 13.

SHAT 32N134, Dr. 1: 23e DI – JMO (24 août 1939 au 11 juillet 1940), 19 and 22 May 1940.

Op. cit., 29 May.

SHAT 32N182: 29e DI Alpine – Général Gérodias, ‘Souvenirs de guerre, 1939–40’, p. 22.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 236

236 Martin S. Alexander

To disrupt intelligence-gathering further, Wehrmacht raids kept

French outposts busy in self-defence. On 2 June, just as a stream of

German vehicles, including lorries pulling tarpaulin-covered trailers, became visible on the Brie to Prusle road, German infantry suddenly emerged from the cemetery at the northern edge of the village of

Brisot and tried to rush the French strong point at Hill 82.

76

Though the attack was beaten off, the Germans tried a night-time infiltration at 02.00 on 3 June between Hill 82 and St Christ. Later on 3 June, 40

Minenwerfer rounds bombarded Epénancourt to keep French heads down.

77

The 29th Alpine Division’s outposts were strafed for 30 minutes that afternoon: ‘numerous aircraft sweeping in at very low altitude that machine-gunned Languevoisin in particular, and circled over the whole sector’.

78

The ‘aggressive behaviour’ of the German ground troops coincided with preparations visible through field glasses north of the Somme canal, while 23rd Infantry Division got ‘various indicators of important movements in the enemy rear areas’ on 2 June and

‘incessant noise signifying continuing movements in the enemy rear areas’ during the night of 3–4 June.

79

Lacking specific intelligence, however, the French could aim only general ‘harassing fire’ at the enemy, the 94th Mountain Artillery Regiment discharging 200 shells in five hours during the night of 3–4 June.

80

Positioning the precious French counter-attack reserves in particular – the DCR tank formations and half-mechanized DLCs – was little better than a lottery.

81

Army and corps staffs were as much in the dark as frontline officers whose men would receive the enemy blows. Baudouin, commanding 13th Infantry Division, recorded that: ‘we divisional generals, spread out along the Somme, had such poor intelligence that we thought ours was a covering and sacrificial role, to allow time to be won and a defence organized to the rear on the Oise, the Seine, the Loire perhaps’.

82

Such misapprehensions were the cause of much later bitterness.

The 29th Alpine’s chief of staff, Major Petetin, became so desperate for solid information about enemy preparations and order of battle that he ordered every infantry battalion in the division to prioritize tactical intelligence-gathering. Regimental intelligence officers were instructed to telephone reports at 05.00, 08.30 and 18.00 hours and provide a written intelligence briefing covering the previous 24 hours by 06.00 on 5 June.

83

80

81

82

83

76

77

78

79

SHAT 32N184, Dr. 4: 29e DI, Etat-Major: 2e Bureau, no. 215/3, 2 June 1940 – compterendu de situation no. 4.

Op. cit., Dr. 10: no. 532/2, 3 June 1940, compte-rendu de renseignements no. 5, du 2 juin, 8h, au 3 juin, 8h.

Op. cit., no. 534/2: compte-rendu de renseignements du 3 juin 1940 de 8h à 18h.

Op. cit., no. 236/3, 4 June 1940, 10h48: compte-rendu de situation no. 6, du 3 juin, 8h, au 3 juin, 20h; and 32N134, Dr. 1: 23e DI, JMO, 2 June 1940.

SHAT 32N184, no. 236/3.

SHAT 32N77, Dr. 2: ‘[…] notes du général de division Baudouin’, pp. 11, 12, 14, 16.

Op. cit., p. 12.

SHAT 32N184, Dr. 12: 29e DI (Etat-Major: 2e Bureau, no. 522/2), ‘Ordre particulier pour la recherche du renseignement pour les sous-secteurs’, 3 June 1940.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 237

After Dunkirk 237

Answers were not long in coming. They were delivered, however, not by

French voices down the telephone but by a torrent of German shells, bombs, and bullets.

On the Somme, Case Red commenced at 03.00 on 5 June. Along the length of 7th Army’s front the dawn sky ‘was lit by the flash and flare of a thunderous air and artillery bombardment’.

84 Masking the precise dispositions of the Wehrmacht over the previous 10 days was a significant and overlooked Luftwaffe contribution to the preparation of the offensive, one assisted by the German ground troops’ aggressive protection of their starting positions. Nor did events clarify themselves once fighting resumed. As Cohen and Gooch discerned: ‘The troops suffered […] while their leaders were unable to contact superior headquarters for orders and lacked all but the vaguest notion of the situation.’ 85 The archives confirm the problem. ‘Intelligence reaching me was piecemeal, fragmentary’, recorded General Baudouin; ‘it was difficult to arrive at an accurate picture of the situation. From higher command, from neighbouring units, I had no news.’ 86

The second way the Luftwaffe handicapped French military effectiveness was by interfering with their armoured and motorized infantry counter-attacks. Sometimes this was achieved by strafing and bombing the French units, at other times by forcing refuelling to take place in woods or after dark, leaving the French tanks and tracked-carriers immobilized or too far distant to relieve critically hard-pressed infantry bastions.

An example of the direct intervention occurred on the afternoon of

6 June south of Péronne. Here German infantry and tanks had battered 29th Alpine Division’s positions for a day and a half without success. To the left, however, a salient had been driven by late afternoon on 5 June between the 29th and the neighbouring formation, General

Fernand Lenclud’s 19th Infantry Division. Wehrmacht mechanized elements had ‘attained, attacked or outflanked’ the fortified hamlets of Fonchette, Fonche, Hattencourt, Etalon, Curchy, and Dreslincourt.

But a combined arms counter-attack at 18.00 that evening by a Renault

R35 tank company and a company of Major de Jankowitz’s 65th

Chasseurs alpins battalion recaptured Dreslincourt.

87

The success encouraged the sector’s senior commander, General

Théodore Sciard of I Corps, to attempt a larger-scale counterstroke at noon the next day, 6 June, and scatter the German attackers. As spearhead, Sciard selected Major Dufour’s 25th Battle-tank Battalion from

Welvert’s rebuilt 1st DCR.

88 Dufour had 30 B1bis and R35 tanks available

84

85

86

87

88

Williams, Ides of May , p. 274.

Cohen and Gooch, Military Misfortunes , p. 205.

SHAT 32N77, Dr. 2: 13e DI – ‘[…] notes du général de division Baudouin’, p. 15.

SHAT 34N527: 34th GRDI, Capt. de Lussan: Carnets de route, p. 13, 5 June 1940.

See SHAT 32N447: 1st DCR war diary; also SHAT 32N448 (1st DCR Etat-Major: bulletins de renseignements, studies of 1st DCR in Belgium, maps and aerial photographs of its zone of operations); Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 236–37, 270;

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, pp. 596–97.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 238

238 Martin S. Alexander in three companies. His orders were to roll back the Germans completely and relieve the undaunted alpins . Realizing that the French tanks were setting at risk the entire Case Red assault on the middle Somme, the

German ground commander summoned a ‘massive’ series of Ju 87 Stuka attacks from 12.30 that ‘continued all afternoon’. Dufour had no antiaircraft battery to drive away the air raids, and his two leading companies were forced to abandon their advance and scatter, or be destroyed.

89 The

25th Battalion’s third tank company, however, had manoeuvred meanwhile around Champien, site of 29th Alpine Division’s headquarters, and its nine tanks fought off the panzers till 17.30. Their action enabled the

29th’s staff to slip the German noose, keep the division under command and control, and direct their infantry battalions to begin a fighting retreat to the Oise at Pont-Ste-Maxence and thence eventually to the south of the Loire.

90

French tactics rested on aggressive defence and slowing down the

German operational tempo. Every encircled strong point, enjoined

Weygand’s operational order of 24 May, ‘must hold out at all cost while it awaits relief’ by tactical counter-attacks to sweep away the attackers.

General Frère’s 7th Army order of 29 May elaborated the techniques now felt to work best against Wehrmacht methods, and the evidence in the 7th Army case studies examined here – 13th Infantry Division and

29th Alpine Division – resembles a modernized variant of the flexible defence developed in 1918.

91 The Germans had no option but to make difficult and dangerous assaults. Time and again they had to pick their way through barbed-wire entanglements, anti-tank spikes and minefields, while under intense and pre-ranged fire from sandbagged and fortified buildings. These positions offered a more effective counter to the infiltration and breakthrough tactics than the linear defences that the Wehrmacht had easily unhinged in May. Adapting with impressive speed, French units relearnt war in under three weeks.

92

On the 29th Alpine Division’s eastern sector the French infantry were solidly dug in. For three days they resisted assaults by strong infantry forces backed by plentiful artillery, tanks, and aircraft. Despite their strength, the Germans made only limited inroads, their advance being measured in metres and dead bodies because of the uncompromising and sacrificial resistance of Colonel Mermet’s 6th Chasseurs alpins demi-brigade around Liancourt. Even when a salient was punched into the French lines between Voyennes and Offoy the breach was eliminated

89

90

91

92

AN 496 (Daladier papers) 4/DA7/Dr. 3/sdr.a: Rapport du Cdt. Dufour, 25e BCC

[Bataillon de Chars de Combat]; Saint-Martin notes how French armoured divisions were weakened by having no integral accompanying anti-aircraft batteries: L’Arme blindée française , p. 126.

SHAT 34N52: 34th GRDI – Capt. de Lussan, Carnets de route, pp. 12–16, 5–6 June

1940; Fabre, Avec les héros , pp. 90–92 (seven of the nine French tanks were destroyed);

Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindeé française, pp. 187–88.

SHAT 32N77, Dr. 2: 13e DI - ‘[…] notes du général de division Baudouin’, p. 11;

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, pp. 635–43.

Crémieux-Brilhac, Français , vol. 2, p. 644.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 239

After Dunkirk 239 when elements of 3rd Alpine Regiment and 24th Chasseurs alpins counterattacked and re-established liaison with the formation to 29th Alpine

Division’s east, General Duchemin’s 3rd Light Infantry Division.

93

Weygand visited the headquarters of General Besson, commanding

Army Group no. 3 (to which 29th Alpine Division and its parent formation, 7th Army, belonged) on the afternoon of 5 June. ‘The order I had given to the different key positions to hold their ground, even if encircled and by-passed by enemy tanks’, noted the generalissimo, ‘was hard and almost cruel’. He left Besson, however, having ‘reason to hope it was being respected’.

94

In June 1940 neither German air power nor mechanization was a magic wand to obviate the need for costly battles at close quarters by the ground troops.

95 General Hermann Hoth’s XV Panzer Corps

(Rommel’s 7th Panzer Division and von Hartlieb’s 5th) did, to be sure, wreak havoc below the lower Somme and Bresle that recalled the week from 12 to 19 May. But mostly it was hard and bloody work to dislodge

French resistance. ‘Further east’, in the evidence of a panzer force officer, ‘the German offensive did not go so smoothly. Panzergruppe

Kleist tried in vain to break out of the bridgeheads at Amiens and

Péronne; the French troops in this sector fought with extreme stubbornness and inflicted considerable losses.’ 96

The bulk of its strength being engaged in the aerial battles of 5–15

June, the Luftwaffe’s aid to the Wehrmacht in this stage of the campaign was mainly indirect. In several instances it dispersed French armour that had been ordered to relieve embattled infantry redoubts and delayed the armour’s return to combat. But it did not blast the French infantry, artillery, and combat engineers from their defences as it had often done three or four weeks earlier.

97 On 14 June the Germans entered Paris and their air force was, in a revealing directive, instructed ‘to help […] maintain momentum, hinder the retreat of enemy forces and disrupt the enemy rail network’.

98 Even in the final 10 days of operations in France, the battles on the ground had to be won by troops on the ground.

III. French Armour in 1940: Organization, Radius of

Action, and Communications Problems

The most serious effect of German air power was how it cramped manoeuvre by French reserves that feared air attack. This particularly

94

95

96

93

97

98

SHAT 32N182, Dr. 4: 29e Div. Alpine, no. 253/3: compte-rendu succinct des opérations, p. 3.

Gen. M. Weygand, Recalled to Service (London, 1952), p. 122.

Facon, L’Armée de l’air , pp. 228–36, on the aerial struggle of 5–15 June.

Maj.-Gen. F.W. von Mellenthin, Panzer Battles: A Study of the Employment of Armor in the

Second World War ([Norman, OK, 1956] New York, 1990), pp. 24–25.

AN 496 (Daladier papers) 4/DA7, Dr.3/sdr.a: Rapport du Commandant Dufour,

25e BCC.

Hooton, Phoenix Triumphant , p. 266.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 240

240 Martin S. Alexander affected tank forces. Weygand and his subordinate commanders needed their armour for fast and mobile counterstrokes. German spearheads overextended themselves at many points in the battle of France. This offered opportunities for French tanks and mechanized cavalry to hurt them and then pull back, without a battle of attrition. French armour was a defensive force-multiplier with significant combat advantages.

Most German tanks were puny, three-quarters being obsolete Panzer

Mk Is and Mk IIs.

99

On the French side, however, the Char B1bis was formidable. It packed a hard punch with a hull-mounted 75 mm gun and a turretmounted 47 mm gun. So did the Somua S35 with its 47 mm turret gun, while the Renault R35 and its uprated successor, the R40, were also tough opponents. In tank-on-tank encounters the French were better protected and usually more powerfully armed than their opponents

(the few Panzerkampfwagen Mk IVs with their 75 mm gun excepted).

100

Technical comparisons, however, hide part of the story. French ‘jab– move–jab’ counterstrokes were hampered by three other – interrelated – factors: insufficient concentrated tank forces, insufficient combat range for their key tank types, and insufficient radios to facilitate tactical control and fast, co-ordinated manoeuvre.

The insufficient concentration of French tanks in large formations

(brigades or divisions) reflected pre-war disputes whether tanks were primarily for infantry support, in defence or attack, or for employment en masse – with attached mechanized infantry and mobile artillery to secure the ground the tanks won and provide fire support. There were, in May–June 1940, three DLMs and three DCRs (with de Gaulle’s

4th DCR forming as battle commenced in May). This amounted to about 1200 tanks. Many more tanks remained dispersed: about 1800 tanks in 40 independent battle-tank battalions (BCCs: bataillons de chars de combat ).

101

In December 1939 General Gaston Billotte (general officer commanding Army Group no. 1 in May 1940) had recommended ‘increasing our number of large mechanized formations’ in case the battle ‘begins in

Belgium with a “rush” of German armoured divisions’. Billotte had stressed the need for time together to ‘give them the necessary cohesion and train commanders able to manoeuvre them’. The severe winter of

1940 left training time in very short supply, however, and the operations of May 1940 particularly exposed the ignorance of senior officers – corps and army commanders – about how to combine the mechanized

99

100

101

Their fast road speed came at the price of poor rough-terrain ability, thin armour-plate, and machine-gun armament; in French nomenclature they would not have been classed as tanks but only ‘auto-mitrailleuses’ – mechanized machine-gun carriers.

Frieser, Blitzkrieg Legend , pp. 35–44, concurs that ‘it was not the thickness of the armor and calibre of the gun […] but entirely different factors that determined the success of the German Panzer force’ (p. 44); cf. Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindée française , pp. 113–14, pp. 119–20. Macksey, Guinness Book of Tank Facts , pp. 71–72, 85–86, 96, 107–14.

Saint-Martin, L’Arme blindée française , pp. 81–83.

War in History 2007 14 (2)

219-264 WIH-075873.qxd 21/3/07 9:45 AM Page 241

After Dunkirk 241 and armoured divisions effectively with infantry formations and supporting corps artillery.

102

The second factor was the fear of the Luftwaffe. This stirred anxieties that tugged in the opposite direction to Billotte’s recommendation of more divisions combining tank battalions with mechanized infantry and integrated artillery, engineers, and anti-tank guns. With the risks of attack from the air weighing heavily on the minds of

French commanders, the distribution of the bulk of their tanks in

‘penny packets’ – individual tank battalions – was attractive. Dispersal presented Hermann Goering’s aircrews with fewer large and easy-tolocate targets.

The air threat, furthermore, intersected with the organization of

French armour via the so-called ‘radius of action’ dilemma. For range was crucial to tank manoeuvre and it was refuelling that gave the

French army 4e Bureau , the logisticians, its greatest headaches. These were most painful in respect of the Char B1bis and the Hotchkiss H39.