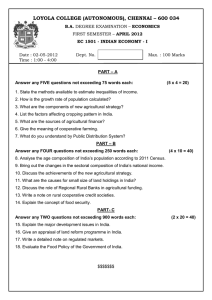

SSC4604 week 7: Governing for global food security M.Juntti@mdx.ac.uk Learning objectives • Food security and the prevalent threats (the problem) and sustainable food • Food sovereignty as an alternative paradigm (the critique) and food ethics • The global agri-food commodity networks (the context) • The right to food • Some potential future scenarios The four pillars of food security • Availability – Supply: production, stocks, trade • Access – Incomes, markets, prices • Utilization – Ability to benefit from a range of nutrients – Determined by care, feeding practices, food preparation methods, dietary diversity, intra household food distribution • Stability – Fluctuation in the above over time THE PROBLEM Global food production will need to meet the requirement of a 60% increase in the production of staple foods to meet the projected increase in demand over the coming decades to 2050 (FAO, 2013). The FAO measures food security with the Food Insecurity Index which is based on household surveys and other secondary data gathered in 140 countries world wide. So where does sustainability come in? • Sustaining availability of course… • Sustaining productive resources – Land – desertification – Water – droughts and depletion of ground water resources • Sustaining the other functions that these resources support – Biodiversity, habitats and ecosystems more broadly • Mitigating the climate impact of food production – CO2 and MH4 emmissions Critique of food secruity: food sovereignty • “the right of individuals, communities, peoples and countries to their own agricultural, labour, fishing, food and land policies which are ecologically, socially, culturally and economically appropriate to their unique circumstances”. www.foodethicscouncil.org Food security and sovereignty locally • • • • Food intake – nutrition, safety and cultural preferences Food production – who profits, environmental impacts Trade security – food self-sufficiency, food availability at origin Agricultural potential – self-sufficiency in domestic foods • A NORTH-SOUT DIVIDE IN LOCAL LEVEL FOOD SECURITY GLOBALLY… • In developed countries: maintaining food production and market access but also • Exporting capacity, quality of products and environmental impact of production are concerns associated with food security Pressures: prices and productivity Global agri-food commodity network • The interdependencies of global food production • Large growers > marketing organisations > export/import agencies > supermarkets > consumers • National polices and international food health, safety and sustainability standards Agricultural imports form developing countries (million euros) • Commodity networks as webs of interdependence – Commodity exchange relationships – Supported by information and technology which bind in further agents – Eg. research; development; NGOs; consumer groups... • Power in commodity networks – ‘Core’ establishes guidelines / codes of practice / demand that is imposed over the ‘periphery’ The HVF network linking the UK and South Africa The production sphere • Sites of import, export and production • Governed by possible national legislation – Employees rights, wages, safety etc. – Health and quality of products – Environmental • National and international advocacy and advisory agents • Export and import standards – Phytosanitary and sanitary standards – International retailers’ quality standards • Export and import levies • Intermediaries (small scale producers) – Contracts with ‘distributors’ – Auction houses – Non-appoinetd agents who offer cash at farm gates... Source: Grievink 2003 OECD conference presentation The influence on agricultural practices • The dis-embeddedness of agriculture – The immediate relationship with the local ecosystem • Mutual dependence • Creating the countryside – The need to meet societal demands • From food shortages to • Consumer trust – The agrarian question: the needs and prospects of farmers and agricultural labour • Viable livelihood • Rural communities • Shift from the regime of regional farming styles to a sociotechnical regime - Detachment from the 3 aspects of embeddedness Logic of disembedded finance capital The hollowing out of the state The power of wholesalers and retailers in the food chain The role of commodity speculation in food prices • Soft commodities market based on a system of predicting stock availability and price – buying and selling, mainly by large investors, in order to gain profit. • Speculative pricing, rather than based on certain knowledge of harvest and market conditions. – Based on changes in other market conditions such as price of oil or speculative buying • High Frequency (HF) or algorithmic trading – super-fast computers monitor minuscule movements to interest rates, prices and other market conditions and execute deals often with minimal human interference • Contributes to price increases and increases volatility of prices which is bad for farmers / a stable production base Pressures: climate change and land degradation Projected changes in agricultural productivity to 2080 -50% +35% Vulnerability to climate change Pressures: changes in land use • Neo-productivism: biofuels – Many countries subsidise – Potential conflict with food security • Climate change mitigation and adaptation – Rural industries (agriculture) as sources of GHG – The role of rural ES in adaptation (buffering the impact of climate change) Solutions / responses Solutions and responses I: subsidies The CAP • A system of farm support that carries with it a set of standards for production methods and certain aspects of the quality of production • Influential for farming, agricultural markets and rural areas within Europe – – – Influences farm income through the Single Farm payment (SFP), production quotas, subsidy ceiling Influences imports and exports and increasingly, the value of the countryside in terms of the environmental goods it consists of. • Both objectives and instruments have evolved in its 50+ year lifetime • The CAP influences the use and management of some 180 million hectares of land across 27 EU Member States • Cumbersome decision-making, fraud The scene at the birth of the CAP (1957) • Post war Europe (EC6) of food shortages and even famine • Low levels of production and low income • Long pre-war traditions of state intervention in agriculture The 4 motives of the CAP defined in the Treaty of Rome in 1957 • Food security, in terms of sufficient quantity rather than quality • Increasing agricultural productivity through technical progress • Agricultural market stabilisation • Reasonable standard of living for European farmers • Combination of productivist and social motivations justify the special treatment granted to agriculture The 5 initial principles of operation • Free circulation of agricultural commodities within the EU • Guarantee of single minimum prices for each agricultural commodity within the Union (the intervention or floor price) • Preference to products from within the boundaries of the Union (import taxes) • Support for exports to compensate for the difference of the EU floor price and the world price of the product in question (restitution payments) • ‘Financial solidarity amongst Member States’ – EAGGF (European Agricultural Guarantee and Guidance Fund) financed from – The income from levies on imports of agricultural products into the EU and of – Direct contributions from each Member State, based on each country’s annual Value-Added-Tax yield. The CAP instruments today - compulsory • The Basic Payment Scheme (BPS) – annual lump sum allocated according to ‘entitlements’ based on previous production and land area. • Green direct payments (30% of direct payment envelope) – conditional on maintenance of grassland; crop diversification and up to 7% under ecological focus (fostering benefits for the environment, improve biodiversity and maintain attractive landscapes such as landscape features, buffer strips, afforested areas, fallow land, areas with nitrogen-fixing crops). • Young farmers scheme – top up for new starters under 40yrs • All CAP payments subject to cross compliance: compulsory compliance with – food safety, animal health, plant health, the climate, the environment, the protection of water resources and animal welfare. – Maintenance of “Good Agricultural and Environmental Condition” of farmland. Decoupled subsidies Who is involved in the CAP and how? • The governments of the Member States • The European Commission • The agricultural policy sectors of the individual Member States • Farm organisations in the Member States and the EU farmers’ union federation (COPA) – Make decisions on levels and forms of subsidies in the Agricultural Council of the EU – Take part in management committees of each CMO – An administrative body – Guard the interest of agriculture in the development of the CAP – Lobby and in many cases hold constitutional rights of consultation • Environmental agencies and NGOs • Agricultural buyers, processors and traders • The consumers / taxpayers • Individual farmers! – Lobby and advice on environmental issues – Profit most from the export subsidies and the price support! – Fund the CAP through taxes Diverse interests promoting diverse policy objectives • • • • • • Fostering world trade; Managing market risks; Contributing to global food security; Ensuring food safety; Providing renewable feedstocks; and Safeguarding water quality and biodiversity. Solutions and responses II: Trade agreements • For example the TTIP: what is this and how does it potentially impact food security? • The new alliance on food security is a US led G8 countries’ commitment to address food security in Africa with the help of private companies: you can read the fact sheet here – What do you know about this alliance? Solutions and responses III: The right to food • The obligation to respect existing access to adequate food requires States parties not to take any measures that result in preventing such access. • The obligation to protect requires measures by the State to ensure that enterprises or individuals do not deprive individuals of their access to adequate food. • The obligation to fulfill (facilitate) means the State must pro-actively engage in activities intended to strengthen people's access to and utilization of resources and means to ensure their livelihood, including food security. • Mainstreaming the right to food in Africa The FAO • Three main goals are: – the eradication of hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition; – the elimination of poverty and the driving forward of economic and social progress for all; and, – the sustainable management and utilization of natural resources, including land, water, air, climate and genetic resources for the benefit of present and future generations. Emerging food governance actors: indigenous people • 2015 was the ‘year of soils’ and FAO has initiated collaborations with indigenous people to mark this – “Many advances in agriculture, forestry and fisheries production are born from indigenous practices and the knowledge of indigenous people” (Director General Da Silva, FAO) • A combination of traditional knowledges and knowhow and new technologies are seen as a key to sustainable development. • 3/4 of world’s agricultural holdings are smallholdings (farms of less than 1 hectares in size) The responses to increasing global food insecurity: 3 models for agricutlure • Productivism – Technological development and large scale efficient production as the solution to the increasing demands for food by an ever growing global population with increasingly homogeneous tastes. – This agenda is driven by actors such as the World Trade Organisation (WTO) where the free movement of goods in the market is seen as leading to efficiency maximising wellbeing and food security overall. • Multifunctional agriculture – Driven by smaller global actors such as NGOs and individual governments, which emphasises the implications this neo-liberal approach has on smaller and marginal actors such as family and subsistence farmers, the global poor. – Promotes a model of agriculture relying on shorter commodity chains, smaller scale production and more decision-making power at the operative level of producers and consumers. • Sustainable productivism ► The dominant food regime causes negative side-effects. ► Agro-ecological approaches can contribute to meeting future food demands, especially in developing countries. ► Agro-ecological approaches can contribute to a ‘real green revolution’; but this requires a move to a new type of agrifood eco-economy. ► Real ecological modernisation can be up-scaled; but this depends on three major conditions.: 1. developing an understanding of how existing contextual solutions can be translated into other environments 2. developing ‘enabling’ policy and building new alliances 3. Building the agri-ecological paradigm through enhanced and engaging research and development What should consumers do: ethical food What lessons for governance? • Supporting sustainable local food • Ethical trade agreements – Fairtrade? • • • • Transparent commodity networks Checks on supermarket pricing mechanisms Food labelling Checks on biofuel imports Further reading • Bergius et al. 2018 Expanding large scale agriculture in the name of the green economy in Tanzania. https://greenmentality.org/2018/05/10/expanding-large-scale-agriculturein-the-name-of-the-green-economy-in-tanzania/ • Gallent N., Hamiduddin I., Juntti M., Kidd S. and Shaw D. (2015) Introduction to Rural Planning. Routledge. • HLPE 2012 Food security and climate change. A report by the High Level Panel of Experts on Food Security and Nutrition for the Commission of the Committee of World Food Security. FAO: Rome. • Horlings L. and Marsden T. (2011) Towards the real green revolution? Exploring the conceptual dimensions of a new ecological modernisation of agriculture that could ‘feed the world’. Global Environmental Change 21: 441-452 • McDonagh J. (2015) Rural Geography II: discourses of food and sustainable rural futures. Progress in Human Geography 38(6): 838-844