[

research report

]

H. JAMES PHILLIPS, PT, PhD1 • JOSEPH BILAND, PT, DPT2 • RICARDO COSTA, PT, DPT3 • REGINE SOUVERAIN, PT, DPT4

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on June 20, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

Five-Position Grip Strength Measures

in Individuals With Clinical Depression

C

linicians involved in the measurement of muscular strength

are often concerned with the sincerity of effort in their patients.

One test purported to identify sincerity of effort is 5-position (or

5-rung) grip strength dynamometry. First described by Stokes

in 1983,20 the dynamometer allows adjustment of a single handle in

each of 5 positions, ranging from a very close grip to a very wide grip.

Based on muscle length-tension relationships, patients offering true

maximal effort should produce a skewed,

bell-shaped curve, plotted as force output against handle position, while those

exerting less than maximal effort should

produce an erratic or “flat” force curve.

TTSTUDY DESIGN: Case-control study.

the participants’ diagnosis.

TTOBJECTIVES: To compare the results of

5-position grip strength testing between a group of

individuals newly diagnosed with clinical depression and a group of age-matched and sex-matched

individuals without depression.

TTBACKGROUND: Clinicians often employ 5-position (or 5-rung) grip strength dynamometry as a

measure of sincerity of effort. However, patients

with clinical depression are known to show altered

performance on motor skill tests. Therefore, the

results of 5-position grip strength dynamometry

in the clinically depressed may be subject to

misinterpretation.

TTMETHODS: Consecutive patients newly

Several subsequent studies have verified

the original claim of Stokes that the test

is an effective measure of sincerity of effort,7,11,14,15,21 while others have questioned

the claim,1,18 suggesting that factors other

diagnosed with clinical depression (n = 45) and

age- and sex-matched individuals without clinical

depression (n = 45) were recruited over a 3-month

period. Each group underwent identical 5-position

grip strength testing of both hands. Measures

were analyzed using a statistical analysis method

based on an 8.5-lb (3.83-kg) SD cutoff and visual

analysis of force curve plots by clinicians naïve to

TTRESULTS: Participants with clinical depression

had an SD equal to or less than 8.5 lb in 60 of 90

hands tested, while the participants in the control

group had an SD equal to or less than 8.5 lb in 1

of 90 hands. Clinicians who analyzed force plots

considered participants with depression to have

exerted “limited effort” in 70% of cases and those

who were not depressed to have exerted limited

effort in 18% of cases.

TTCONCLUSION: A high percentage of individuals

diagnosed with clinical depression produced

statistical and graphical representations of 5-position grip strength measures that suggested poor

volitional effort, which is often interpreted as lack

of sincerity of effort. Clinicians unaware of the

presence of clinical depression in patients could

misinterpret the results of 5-position grip strength

testing in this population. J Orthop Sports Phys

Ther 2011;41(3):149-154, Epub 2 February 2011.

doi:10.2519/jospt.2011.3328

TTKEY WORDS: dynamometry, hand, sincerity

of effort

than effort may influence the shape of the

force output curve.5,8,18,22

One group of patients known to have

altered performance on motor skill tests

are those with clinical depression.4,17

Studies have shown ease of fatigability

and lack of asymmetry of grip strength

among depressed boys,4 generally reduced force output among depressed individuals compared to age-matched and

sex-matched nondepressed persons,17 and

a correlation of improved grip strength to

improved affect following intervention.13

However, to the authors’ knowledge,

5-position grip strength testing has never

been administered to clinically depressed

individuals.

The interpretation of results of 5-position grip strength testing has been questioned. In a review of related literature,

Shechtman et al18 found no less than 4

different methods of interpretation: (1)

visual inspection of the force curve for the

skewed, bell-shaped curve; (2) analysis

of variance (ANOVA), with a significant

interaction between handle and effort

deemed as an indicator of maximal effort;

(3) calculation of SD of the 5 scores, with

a significantly smaller SD expected for

those exerting submaximal effort; and (4)

normalization of the 5 scores, expressed

as a percentage of the third position, or

maximum score, plotted by handle position. Shechtman et al18 investigated

these 4 interpretation methods among

individuals asked to exert full effort, then

feign weakness, in both their injured and

1

Associate Professor, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ. 2Adjunct Instructor, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ. 3Staff Physical Therapist, MSI Physical Therapy,

Kenilworth, NJ. 4Staff Physical Therapist, Memorial Sloan Kettering, New York, NY. The protocol of this study was approved by The Institutional Review Board of Seton Hall

University. Address correspondence to Dr H. James Phillips, Department of Physical Therapy, Seton Hall University, South Orange, NJ 07079. E-mail: howard.phillips@shu.edu

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 41 | number 3 | march 2011 |

41-03 Phillips.indd 149

149

2/24/2011 4:36:52 PM

METHODS

Participants

O

ne hundred consecutive individuals, newly diagnosed but untreated for clinical depression at a

single private psychiatry practice, were

A

Force (lb)*

uninjured hands. On visual inspection

of the 5-position curve, they found no

difference between the uninjured hand

feigning weakness and the injured hand

exerting full effort. They did, however,

see significant differences using the SD

method, which suggested that individuals

exerting true maximal effort might have

greater differences among grip positions,

thus a higher SD, and those offering less

than maximal effort might have less difference among positions, thus a lower

SD. In a separate study, Gutierrez and

Shectman8 found that an SD cutoff of 8.5

lb (3.83 kg) provided optimum sensitivity and specificity in detecting insincere

effort (0.70 and 0.83, respectively). But

they also found a strength-dependent

correlation, with stronger individuals

producing typical bell-shaped curves and

weaker individuals producing somewhat

flatter curves, and cautioned against the

use of this test as a measure of sincerity of

effort. However, Hoffmaster et al11 found

differences in the 5-position curve pattern between sincere and feigned efforts

that supported the original paradigm of

Stokes. An acknowledged shortcoming of

these studies is that the participants were

asked to feign weakness by exerting 50%

or less effort, whereas individuals intentionally feigning weakness may behave

quite differently.

The purpose of this study was to have

individuals newly diagnosed with clinical

depression, but not yet treated, undergo

5-position grip strength testing and compare their results to age-matched and

sex-matched individuals without depression. Both the results of visual inspection

of plotted 5-position graphs by clinicians

from various disciplines in rehabilitation

medicine and the SD method were used

for comparison between groups.

research report

130

120

110

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

Hand Position

B

Force (lb)*

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on June 20, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

[

130

120

110

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1

2

3

4

5

Hand Position

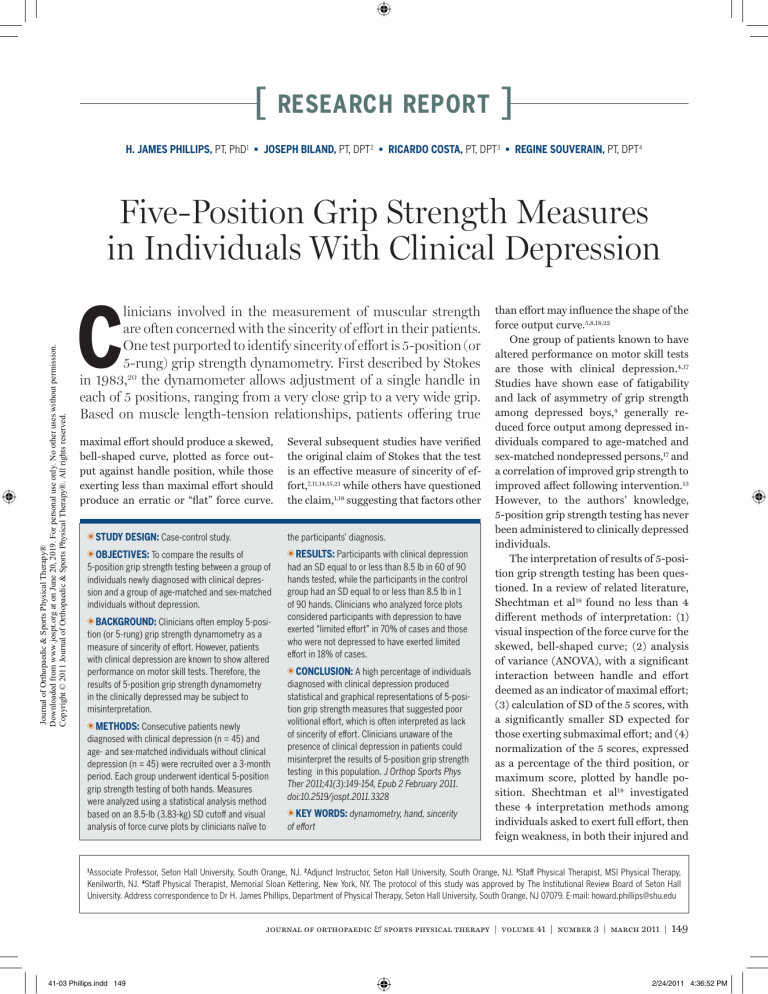

FIGURE. Sample 5-position graphs for clinician

sorting. (A) Right-hand grip, 40-year-old, righthanded male. Example of participant with depression

producing a “flat” force curve, resulting in clinician

sorting as “less than full effort.” (B) Left hand

grip, 55-year-old, right-handed male. Example of a

participant in the control group, producing a typical

bell-shaped curve, resulting in clinician sorting as

“full effort.” *1 lb is equivalent to 0.45 kg.

invited to participate in the study, 45 of

whom agreed to participate. The psychiatry practice was located in a major

Northeast inner city, with a largely Spanish and Portuguese population. Investigators working with the participants in

the study were fluent in English, Spanish,

and Portuguese. All diagnoses were made

by a single board-certified psychiatrist

with over 35 years of clinical practice.

To be eligible for the study, individuals

had to have been diagnosed with major depressive disorder (DSM IV 296.3)

and to have presented with “moderate”

symptoms. Those with “mild” or “severe”

symptoms were excluded. To prevent the

possibility of coercion, the treating physician was then blinded to the individuals’ participation in the 5-position grip

]

strength testing study. Forty-five agematched and sex-matched individuals

without clinical depression were recruited as a control group. Age matching for

each participant in the control group was

within 0 to 5 years of a participant with

depression. Individuals in the control

group were from a sample of convenience

and represented a diverse ethnic population recruited via flyer on the campus of

Seton Hall University. All participants in

the control group were naïve to the purpose of the 5-position grip strength testing (no healthcare practitioners or health

professions students were recruited) and

deemed to represent the general campus community. Informed consent was

obtained from all participants in accordance with the policies and procedures

of the Seton Hall University Institutional

Review Board. Exclusion criteria included pregnancy, rheumatoid arthritis or

other systemic arthritis affecting joints

of the upper extremities, any neurological

or musculoskeletal disorders that could

affect arm function, and any psychological comorbidities other than clinical

depression.

Setting

Grip strength testing for all individuals

newly diagnosed with clinical depression

was conducted in a single private psychiatry office on the day of their diagnosis.

Individuals without clinical depression

were tested in various settings but always

following the identical methodology described below.

Instruments/Procedure

A single JAMAR 5-position grip strength

dynamometer (Sammons Preston,

Bolingbrook, IL) was calibrated according to the manufacturer’s specifications

and used for all testing.10 Individuals

newly diagnosed with depression but not

yet treated were invited to join the study

on the day of their initial psychiatric examination. Individuals were encouraged

to sit upright in an armless chair, with

their elbow bent to 90° and forearm in

neutral position. One measure represent-

150 | march 2011 | volume 41 | number 3 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

41-03 Phillips.indd 150

2/24/2011 4:36:53 PM

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on June 20, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

ing a maximal effort was taken for each of

the 5 positions for each hand, beginning

with the narrowest and progressing to the

widest position of the dynamometer, with

individuals alternating hands at each grip

setting. Results were recorded in tabular

form in 1-lb (0.45-kg) increments for

later statistical and graphic analyses.

The clinicians participating in this study

used pounds, rather than kilograms, because they indicated that this was the

most common measure used, particularly when producing 5-position graphs

for visual examination. Age-matched and

sex-matched individuals without clinical

depression were tested in the same manner in various settings but always with

similar seating, identical commands, and

the same calibrated dynamometer.

The SD for the force produced in the 5

handle positions for each hand was determined, with a cutoff of less than or equal

to 8.5 lb8 considered an exertion of less

than full effort. Grip strength measures

were plotted against hand position, using

a separate line graph for the right and left

hands of each individual (FIGURE). Grip

dynamometer measures were recorded

in 1-lb (0.45-kg) increments and rounded

to the nearest 10-lb (4.5-kg) increment to

facilitate graphing. Each graph was plotted by a single investigator and received

a numeric code, known only by the primary author, to identify the participant

as clinically depressed or not depressed.

Left- and right-hand graphs for each participant were printed on separate pages,

with gender, age, and handedness noted.

The pages were stapled together for later

interpretation by clinicians.

Next, 4 clinical rehabilitation specialists (TABLE 1) familiar with interpretation

of 5-position grip strength graphs were

asked to sort the graphs according to

whether they considered the participant

to have exerted full effort or less than full

effort. Each clinician indicated that they

routinely used graphical interpretation of

5-position grip strength testing in clinical

practice, usually with data measured in

pounds and plotted in 10-lb increments.

They received no further instruction in

TABLE 1

Profiles of the Practitioners Who

Visually Sorted 5-Position Graphs

Practitioner

CHT

Years Experience

Practice Setting

Physical therapist

No

22

Private practice

Occupational therapist

Yes

30

Private practice

Physiatrist

No

24

Private practice

Psychologist

No

28

Veteran’s hospital

Abbreviation: CHT, certified hand therapist.

TABLE 2

Groups

Number of Participants in Each Group

With an SD Less Than or Equal to,

and Above, 8.5-lb (3.83-kg) Cutoff

Less Than or Equal to 8.5-lb SD

Greater Than 8.5-lb SD

Depressed, right hand (n = 45)

29

16

Depressed, left hand (n = 45)

31

14

Nondepressed, right hand (n = 45)

1

44

Nondepressed, left hand (n = 45)

0

45

how to interpret the graphs, relying on

past experience for interpretation rather

than a new construct. Raters were instructed to designate the participant as

exerting “less than full effort” if either the

left- or right-hand graph suggested less

than full effort. Raters were naïve to the

purpose of the study and the psychological disposition of the participants, and

did not have access to results of the SD

calculations. Each clinician rater calculated the percentage of those deemed less

than full effort out of the total number of

participants (n = 90). Reliability among

the 4 raters was calculated using percent

agreement.

RESULTS

U

sing the SD method with a cutoff of less than or equal to 8.5 lb

(3.83 kg), we found that individuals with depression had a SD score of 8.5

or less in 60 of 90 cases (66.6%), while

those without depression had scores of

8.5 or less in just 1 of 90 cases (1.1%)

(TABLE 2).

Results of clinician sorting of graphs

are shown in TABLE 3. Overall, for the

group recently diagnosed with clinical

depression, clinicians perceived 70%

(67% to 76%, depending on the clinician) of the graphs as representing less

than full effort, compared to 18% (11% to

24%, depending on the clinician) of the

graphs for those without clinical depression. Percent agreement among the 4 raters was 88.2%.

Given the observable differences between the 2 diagnostic groups using

both methods, tables of relative risk of

misidentifying an individual with depression as volitionally exerting less than

full effort were developed (TABLES 4 and

5). On average, clinicians selected individuals with clinical depression as exerting less than full effort 4 times as often

as individuals in the control group. Using the SD method, with a cutoff of less

than or equal to 8.5 lb, the relative risk

of misidentifying individuals with clinical depression as exerting less than full

effort was 60 times that of misidentifying

individuals without clinical depression.

DISCUSSION

T

he aim of this study was to determine if individuals with clinical

depression would perform differ-

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 41 | number 3 | march 2011 |

41-03 Phillips.indd 151

151

2/24/2011 4:36:54 PM

[

TABLE 3

research report

Results of Clinicians Asked to Sort

5-Position Graphs as Limited or Full Effort*

Groups

Depressed (n = 45)

Nondepressed (n = 45)

Physical therapist, limited effort

34 (76%)

7 (16%)

Occupational therapist, limited effort

30 (67%)

9 (20%)

Physiatrist, limited effort

30 (67%)

5 (11%)

Psychologist, limited effort

31 (69%)

11 (24%)

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on June 20, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

*Values are n (%). Overall rate of individuals with depression sorted as performing a limited effort

was 69.75%. Overall rate of individuals without depression sorted as performing a limited effort was

17.75%.

TABLE 4

Relative Risk of Persons With

Clinical Depression Labeled as Providing

“Less Than Full Effort” by Clinician Raters*

Depressed (n = 45)

Nondepressed (n = 45)

Less than full effort

32

8

Full effort

13

37

*Relative risk: 4.0; 95% CI: 1.7, 9.6.

TABLE 5

Relative Risk of Persons

With Clinical Depression Labeled

as Providing “Less Than Full Effort” Using

the 8.5-lb (3.83-kg) Cutoff SD Method*

Depressed (n = 90 hands)

Nondepressed (n = 90 hands)

SD Less than or equal to 8.5†

60

1

SD greater than 8.5

30

89

*Relative risk: 60.0; 95% CI: 8.2, 440.

†

An SD less than or equal to 8.5 is considered less than full effort.

ently than individuals without depression

when tested with 5-position grip strength

testing. While decreased motor output

among individuals with clinical depression has been previously described,4,13,17

to our knowledge, this is the first time

5-position grip strength testing has been

utilized for this population.

Using the criterion of an SD cutoff of

less than or equal to 8.5 lb, we observed a

difference in individuals newly diagnosed

with clinical depression: they fell below

8.5 lb in 66% of cases, compared to just

1% of cases in those without depression.

Similarly, clinicians naïve to the psychological disposition of the participants,

who visually analyzed the 5-position force

curves, categorized those with depression

as exerting less than full effort in 67% to

76% of cases. Calculated another way,

persons with clinical depression had a

relative risk of being identified as exerting less than full effort 4 times more often

than those without depression by clinicians using interpretation of graphs, and

60 times more often by clinicians using

the method of SD less than or equal to

8.5 lb.

As such, patients with undiagnosed or

undisclosed clinical depression might be

misidentified as “malingerers” or “symptom magnifiers” by clinicians admin-

]

istering this test. This finding may be

important, as Haggman et al9 found that

physical therapists often missed signs of

clinical depression in patients presenting

with low back pain and suggested implementation of a simple screening device

that would alert them to this common

malady. In a recent editorial, Ross and

Boissonnault16 identified clinical depression as a condition that can adversely influence the prognosis of individuals seen

by physical therapists but may not receive

the attention of clinicians, who may be

otherwise focused on screening for red

flags that suggest more serious pathology.

Study Limitations

Because some individuals with clinical

depression declined participation in the

study (55 of 100 consecutive patients declined), a level of self-selection occurred.

While all potential participants with clinical depression were diagnosed with major depressive disorder (DSM IV 296.3)

with moderate symptoms, there is a spectrum of behavioral presentations in this

cohort. According to the 1 investigator

(R.C.) who collected grip strength data

for this group, patients who appeared to

have the highest level of depression often

declined participation, indicating that

they were unwilling to participate and

simply wanted to be treated. However, we

have no objective criteria to definitively

differentiate between those who participated and those who declined. Therefore,

we can only speculate that those who

participated might have had less severe

symptoms of depression than those who

declined. Had those with a more significant presentation of depression participated, we speculate that the differences

between groups would have been even

greater than that shown.

Age- and sex-matched participants

in the comparison group were not specifically screened for depression due to

Institutional Review Board concerns. As

such, some of these individuals might

have had unknown clinical depression

that affected their performance. However, this would have resulted in groups

152 | march 2011 | volume 41 | number 3 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

41-03 Phillips.indd 152

2/24/2011 4:36:55 PM

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on June 20, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

having more similar results rather than

the differences seen.

One potential limitation in methodology is that the researcher plotting

the force curves was not blinded to the

participant group assignment, which

presents a possible bias in producing the

graphs. However, the graphs consisted of

a simple plotting of numeric data, rounded to the nearest 10 lb and marked as an

x. Accuracy of the plots was left to the

integrity of the researcher. Additionally,

rounding to the nearest 10-lb increment

might have caused a “flattening” of the

force curves, particularly for those with

lower measures. However, changing the

scale to 5-lb (2.27-kg) increments, for

example, would only have resulted in a

1- or 2-mm difference in the placement

of the marks, producing minimal change

in the “flatness” or curvilinear shape of

the curve.

Another potential limitation is that

participants were tested on the same day

that they were diagnosed with clinical depression. Their reaction to this new diagnostic label might have affected their

behavior, including the grip strength testing. However, keeping “time living with

diagnosis” the same for all participants

had the benefit of standardizing this potential covariate.

As noted previously, individuals with

clinical depression were of largely Spanish and Portuguese ethnicity, while those

in the control group were a more mixed

ethnic group. However, the investigators

are not aware of any studies that show

any differences among ethnic groups with

regard to grip strength testing outcomes.

Percent agreement among the 4 clinicians analyzing the graphs was calculated

at 88.2%. Considering that the dichotomous choices of full effort and less than

full effort spread over 4 raters would

produce agreement of 20% by chance

alone, this represents fairly good reliability among the clinicians. To the authors’

knowledge, this is the first time that clinicians’ rating of 5-position graphs was

conducted, which suggests that more research is needed in this area.

Finally, clinical depression, ease of fatigue, and volitional limitation of effort

are not mutually exclusive. For instance,

persons undergoing grip strength testing may be clinically depressed and consciously self-limit their effort for a variety

of known and unknown reasons. Patients

seen for physical therapy care may present with a cluster of physical and psychological conditions, making any one

assessment tool insufficient for clinical

determination of sincerity of effort.

CONCLUSION

A

large percentage of individuals newly diagnosed with clinical

depression were erroneously considered to have provided less than full effort on the basis of their performance on

the 5-position hand grip strength test. t

KEY POINTS

FINDINGS: A large percentage of indi-

viduals newly diagnosed with clinical

depression were erroneously considered

as providing less than full effort on the

basis of their performance on the 5-position hand grip strength test.

IMPLICATION: Individuals with clinical

depression asked to perform 5-position

grip strength testing as a measure of

sincerity of effort could easily be mislabeled as volitionally self-limiting effort

by clinicians unaware of their mental

condition. Clinicians need to consider

the mental health status of persons

undergoing this form of testing before

reaching clinical decisions.

CAUTION: This study only looked at 5-position grip strength and was limited

to individuals newly diagnosed with

clinical depression on the day of their

diagnosis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We thank William Mahalchick, PT, OCS, Mary Grossman, OTR,

CHT, Peter Schmaus, MD, and Lawrence

Weinberger, PhD for their assistance in serving as clinician interpreters of the 5-position

grip strength graphs.

REFERENCES

1. B

ohannon RW. Is it legitimate to characterize muscle strength using a limited number of measures? J Strength Cond Res.

2008;22:166-173. http://dx.doi.org/10.1519/

JSC.0b013e31815f993d

2. Carney CE, Ulmer C, Edinger JD, Krystal AD,

Knauss F. Assessing depression symptoms in

those with insomnia: an examination of the beck

depression inventory second edition (BDI-II). J

Psychiatr Res. 2009;43:576-582. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.09.002

3. Dubowitz H, Feigelman S, Lane W, et al. Screening for depression in an urban pediatric primary

care clinic. Pediatrics. 2007;119:435-443. http://

dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2010

4. Emerson CS, Harrison DW, Everhart DE, Williamson JB. Grip strength asymmetry in depressed

boys. Neuropsy Neuropsy Be. 2001;14:130-134.

5. Ghori AK, Chung KC. A decision-analysis model

to diagnose feigned hand weakness. J Hand

Surg Am. 2007;32:1638-1643. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.09.010

6. Golden J, Conroy RM, O’Dwyer AM. Reliability

and validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Beck Depression Inventory

(Full and FastScreen scales) in detecting depression in persons with hepatitis C. J Affect Disord.

2007;100:265-269. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

jad.2006.10.020

7. Goldman S, Cahalan TD, An KN. The injured

upper extremity and the JAMAR five-handle

position grip test. Am J Phys Med Rehabil.

1991;70:306-308.

8. Gutierrez Z, Shechtman O. Effectiveness

of the five-handle position grip strength

test in detecting sincerity of effort in men

and women. Am J Phys Med Rehabil.

2003;82:847-855. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.

PHM.0000083667.25092.4E

9. Haggman S, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. Screening for symptoms of depression by physical

therapists managing low back pain. Phys Ther.

2004;84:1157-1166.

10. Harkonen R, Harju R, Alaranta H. Accuracy of the Jamar dynamometer. J Hand Ther.

1993;6:259-262.

11. Hoffmaster E, Lech R, Niebuhr BR. Consistency

of sincere and feigned grip exertions with repeated testing. J Occup Med. 1993;35:788-794.

12. Homaifar BY, Brenner LA, Gutierrez PM, et al.

Sensitivity and specificity of the Beck Depression Inventory-II in persons with traumatic brain

injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:652-656.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2008.10.028

13. Neuberger GB, Aaronson LS, Gajewski B, et al.

Predictors of exercise and effects of exercise

on symptoms, function, aerobic fitness, and

disease outcomes of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57:943-952. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1002/art.22903

14. Niebuhr BR, Marion R. Detecting sincerity of

journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy | volume 41 | number 3 | march 2011 |

41-03 Phillips.indd 153

153

2/24/2011 4:36:56 PM

[

effort when measuring grip strength. Am J Phys

Med. 1987;66:16-24.

15. Niebuhr BR, Marion R. Voluntary control of submaximal grip strength. Am J Phys Med Rehabil.

1990;69:96-101.

16. Ross MD, Boissonnault WG. Red flags: to

screen or not to screen? J Orthop Sports Phys

Ther. 40:682-684. http://dx.doi.org/10.2519/

jospt.2010.0109

17. Russo A, Cesari M, Onder G, et al. Depression and physical function: results from

the aging and longevity study in the Sirente

geographic area (ilSIRENTE Study). J Geriatr

research report

18.

19.

20.

21.

Psychiatry Neurol. 2007;20:131-137. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1177/0891988707301865

Shechtman O, Gutierrez Z, Kokendofer E. Analysis of the statistical methods used to detect submaximal effort with the five-rung grip strength

test. J Hand Ther. 2005;18:10-18. http://dx.doi.

org/10.1197/j.jht.2004.10.004

Shechtman O, Mann WC, Justiss MD, Tomita M.

Grip strength in the frail elderly. Am J Phys Med

Rehabil. 2004;83:819-826.

Stokes HM. The seriously uninjured hand--weakness of grip. J Occup Med. 1983;25:683-684.

Stokes HM, Landrieu KW, Domangue B,

]

Kunen S. Identification of low-effort patients

through dynamometry. J Hand Surg Am.

1995;20:1047-1056. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/

S0363-5023(05)80158-3

22. Watson J, Ring D. Influence of psychological

factors on grip strength. J Hand Surg Am.

2008;33:1791-1795. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.

jhsa.2008.07.006

@

MORE INFORMATION

WWW.JOSPT.ORG

Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®

Downloaded from www.jospt.org at on June 20, 2019. For personal use only. No other uses without permission.

Copyright © 2011 Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy®. All rights reserved.

PUBLISH Your Manuscript in a Journal With International Reach

JOSPT offers authors of accepted papers an international audience. The

Journal is currently distributed to the members of the following

organizations as a member benefit:

• APTA's Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy Sections

• Sports Physiotherapy Australia (SPA) Titled Members

• Physio Austria (PA) Sports Group

• Belgische Vereniging van Manueel Therapeuten-Association Belge des

Thérapeutes Manuels (BVMT-ABTM)

• Comitê de Fisioterapia Esportiva do Estado do Rio de Janeiro

(COFEERJ)

• Canadian Physiotherapy Association (CPA) Orthopaedic Division

• Sociedad Chilena de Kinesiologia del Deporte (SOKIDE)

• Suomen Ortopedisen Manuaalisen Terapian Yhdistys ry (SOMTY)

• German Federal Association of Manual Therapists (DFAMT)

• Hellenic Scientific Society of Physiotherapy (HSSPT) Sports

Injury Section

• Chartered Physiotherapists in Sports and Exercise Medicine (CPSEM)

and Chartered Physiotherapists in Manipulative Therapy (CPMT)

of the Irish Society of Chartered Physiotherapists (ISCP)

• Israeli Physiotherapy Society (IPTS)

• Gruppo di Terapi Manuale (GTM), a special interest group

of Associazione Italiana Fisioterapisti (AIFI)

• New Zealand Sports and Orthopaedic Physiotherapy Association

• Norwegian Sport Physiotherapy Group of the Norwegian Physiotherapist

Association

• Portuguese Sports Physiotherapy Group (PSPG) of the Portuguese

Association of Physiotherapists

• Orthopaedic Manipulative Physiotherapy Group (OMPTG) of the

South African Society of Physiotherapy (SASP)

• Swiss Sports Physiotherapy Association (SSPA)

• Association of Turkish Sports Physiotherapists (ATSP)

In addition, JOSPT reaches students and faculty, physical therapists and

physicians at more than 1,400 institutions in the United States and around the

world. We invite you to review our Information for and Instructions

to Authors at www.jospt.org and submit your manuscript for peer review at

http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/jospt.

154 | march 2011 | volume 41 | number 3 | journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy

41-03 Phillips.indd 154

2/24/2011 4:36:57 PM