Body Sensor Networks for Sport, Wellbeing and Health

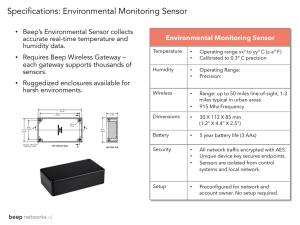

advertisement