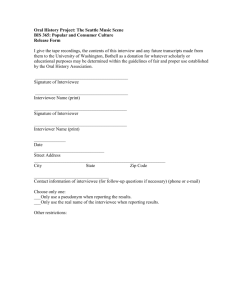

2013 Become a Better Interviewer Become 8/7/19, 4)08 PM a Better Interviewer Well-formed questions and attentive listening skills can help auditors separate truth from deception during interviews. James Ratley June 01, 2013 Imagine that while auditing your organization’s accounts payable process, you find some anomalies that indicate that certain controls involved in the process might not be functioning as intended. You decide to interview Phil, the employee responsible for approving invoices and processing payments. After a brief introduction, you begin asking Phil about the area of concern. Consider the difference between these two opening questions: Is it correct that, once you receive an invoice, you pull the related purchase order and receiving report before approving it? What is your role in the accounts payable process? Although the first question might elicit helpful information, it would encourage Phil to address only that particular piece of the overall function or simply agree with your assertion. The second question, in contrast, prompts Phil to describe his role in the context of the overall process. His response would provide information not only about invoice approval procedures, but also about what Phil views as the important points of his job and even about other areas where the controls need to be shored up — information that would likely be missed if the first question were posed. Now imagine your audit procedures indicate that Phil is actually circumventing the controls intentionally — possibly to conceal a scheme in which he is approving invoices from, and cutting checks to, a shell company that he owns. Which of the two questions would be less likely to clue Phil in as to why you are asking about his area of responsibility? Most internal auditors spend much of their time asking similar questions of staff https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 1 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM members and others to gather information. These interviews are conducted for numerous reasons, including to understand the day-to-day operations of an area, assess internal controls, identify fraud risks, or follow up on tips of potential fraud. However, unlike other evidence-gathering methods, such as reviewing documents and analyzing data, interviewing is a dynamic process that requires auditors to identify often fleeting or subtle pieces of evidence, as well as to be able to adjust their approach quickly in response to new information they uncover. Asking Good Questions Often, how a question is asked is equally important as — or more important than — what is asked. Effective questions allow auditors to obtain the information they seek, identify new areas to explore, and watch for signs of misinformation or deception in responses, all while retaining control of the interview and not providing the interviewee with information indicating what the auditor does or does not know. In contrast, poorly constructed questions can result in the auditor failing to uncover important information, missing opportunities to expand the interview, potentially overlooking warning signs of fraud, and inadvertently revealing the limit of the auditor’s knowledge to the interviewee. Learning the art of effective interviewing takes patience, practice, and planning. This does not mean all questions must be mapped out in advance; many successful interviews are conducted organically, with questions asked off-the-cuff, based on the responses received. However, whether they are crafting interview questions in advance or on the fly, auditors should keep several guidelines in mind. Focus on Clarity Some auditors try to gather as much information using as few questions as possible and end up receiving convoluted or vague responses. Others seek confirmation of every detail, which can quickly turn an interview into an unproductive probing of minutia. Balancing thoroughness and efficiency is imperative to obtaining the necessary and relevant facts without overburdening the interviewee. Because the location of this line varies by interviewee, auditors can find this balance most effectively by ensuring they ask clear questions throughout the interview. Consider, for example, the effectiveness of these two questions in asking about a procurement employee’s purchasing authorization limits: https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 2 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM When you make a purchase, what is the process, and what sort of authorization limits do you have? Can you authorize purchases of more than US $5,000, or do you need a supervisor’s approval to do so? Both questions appear to address the issue, but neither does so effectively. The first is overly broad and requires a complex answer (or two answers), while the second question could be answered accurately with both a “yes” and a “no” and likely would require follow up by the auditor. Convoluted or overly vague questions enable an interviewee to avoid providing false or incriminating information while still responding to a portion of the question that is in his or her comfort zone. Conversely, a clear, direct inquiry, such as “Please tell me about any authorization limits in the purchasing process,” leaves much less room for avoiding the truth. Be Polite Yet Assertive Some individuals might respond to a question in a way that doesn’t provide a direct answer or that veers off topic. Sometimes these responses are innocent; sometimes they are not. To make the most of an interview, auditors must remain in control of the situation, regardless of how the interviewee responds. Being assertive does not require being impolite, however. In some instances, wording questions as a subtle command (e.g., “Tell me about…” or “Please describe…”) can help establish the interview relationship. Additionally, remaining in control does not mean dissuading the interviewee from exploring pertinent topics that are outside the planned discussion points. For example, if an interviewee starts to wander into a different topic that is relevant to the interview but not directly related to the issue in question, the auditor might respond with “I heard you mention Y, and I want to learn more about that. But first, can you continue telling me about X?” In such instances, the interviewer must be mindful of interrupting, as individuals often provide useful information during their digressions. Nonetheless, if the person is not staying remotely on point, the interviewer should not hesitate to bring him or her back on track. Use the Right Types of Questions Interview questions can be structured in several ways, each with its own strengths, weaknesses, and ideal usage. Open questions ask the interviewee to describe or explain something. Most audit interviews should rely heavily on open questions, as https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 3 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM these provide the best view of how things actually operate and the perspective of the staff member involved in a particular area. They also enable the auditor to observe the interviewee’s demeanor and attitude, which can provide additional information about specific issues. However, if the auditor believes an individual might not stay on topic or may avoid providing certain information, open questions should be used cautiously. In contrast, closed questions can be answered with a specific, definitive response — most often “yes” or “no.” They are not meant to provide the big picture but can be useful in gathering details such as amounts and dates. Auditors should use closed questions sparingly in an informational interview, as they do not encourage the flow of information as effectively as open questions. Occasionally, the auditor might want to direct the interviewee toward a specific point or evoke a certain reply. Leading questions can be useful in such circumstances by exploring an assumption — a fact or piece of information — that the interviewee did not provide previously. When used appropriately, such questions can help the auditor confirm facts that the interviewee might be hesitant to discuss. Examples of leading questions include: “So there have been no changes in the process since last year?” and “You sign off on these exception reports, correct?” If the interviewee does not deny the assumption, then the fact is confirmed. However, before using leading questions, the auditor should raise the topic with open questions and allow the interviewee the chance to volunteer information. Listening vs. Hearing If the auditor fails to fully absorb an interviewee’s response, even the best-worded question will be rendered useless. And absorbing the response entails more than hearing what is said; it requires actively listening—that is, paying attention to, interpreting, understanding, and reacting to the interviewee’s meaning, not just his or her words. As with all in-person communication, both parties in an interview use verbal and nonverbal signals to convey messages to each other. Some of these signals are intentional; others are involuntary. Successful interviewers know how to read these signals and adjust their own signals accordingly to encourage the other party to communicate openly. https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 4 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM Communication Facilitators and InhibitorsKnowing what factors can facilitate and inhibit communication can help the auditor put the interviewee at ease (see “Facilitator and Inhibitor Examples” below). Facilitators of communication open the flow of conversations between individuals and motivate them to continue interacting. Other situational factors have the opposite effect; they inhibit communication by making one party unable or unwilling to provide relevant information. By maximizing facilitators and minimizing inhibitors, an auditor can improve the dynamics of interviews and encourage others to provide information openly. Active Participation Active listening is imperative to encouraging interviewee participation. The interviewer’s active participation through verbal and nonverbal cues conveys interest and promotes rapport, thereby increasing the interviewee’s engagement. Some indicators of active participation that can help auditors connect with an interviewee, facilitate communication, and understand the individual’s responses include: Eye contact. The auditor should establish and maintain an appropriate level of eye contact with the interviewee throughout the interview to personalize the interaction and build rapport. However, the appropriate level of eye contact varies by culture and even by person; consequently, the auditor should pay attention to the interviewee to determine the level of eye contact that makes him or her comfortable. Mirroring. People tend to mirror each other’s body language subconsciously as a way of bonding and creating rapport. Auditors can help put interviewees at ease by subtly reflecting their body language. Further, the skilled interviewer can assess the level of rapport established by changing posture and watching the interviewee’s response. This information can help auditors determine whether to move into sensitive areas of questioning or continue establishing a connection with the individual. Confirmation. Confirming periodically that the auditor is listening can encourage interviewees to continue talking. For example, the auditor can provide auditory confirmation with a simple “mmm hmmm” and nonverbal confirmation by nodding or leaning toward the interviewee during his or her response. Attentive echo. When the interviewee finishes a narrative response, the auditor can encourage additional information by echoing back the last point the person made. This confirms that the auditor is actively listening and absorbing the information, and it provides a starting point for the person to continue the response. Periodic summarization. Occasionally, the auditor might summarize the https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 5 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM information provided to that point so that the interviewee can affirm, clarify, or correct the auditor’s understanding. The Interviewer's Role An integral part of internal auditing involves obtaining information from people. Regardless of the interview’s objective, auditors should embrace the role of interviewer and use time-tested techniques. But asking the right questions does not necessarily ensure key information will be uncovered; an effective interviewer also recognizes the need to separate truth from deception. Consequently, crafting effective questions, understanding the communication dynamics at play, actively participating in the interview process, and remaining alert to signs of deception will help auditors increase the effectiveness and efficiency of their interviews and their overall engagements. Facilitator and Inhibitor Examples There are numerous factors that can facilitate or inhibit communication during audit interviews. Examples of communication facilitators include: Recognition. All human beings desire the recognition and esteem of others and often will “perform” in exchange for such acknowledgment. The skillful interviewer takes advantage of every opportunity to give the respondent sincere recognition. Altruism. Many individuals have a deep need to identify with a higher value or cause beyond immediate self-interest. Auditors can call on an individual’s altruism to reinforce the importance of helping the organization and explain how the interview process serves this purpose. Sympathy. People have an inherent desire to share their joys, fears, successes, and failures with others who understand them. Effective interviewers exhibit a sympathetic attitude and encourage the interviewee to open up. Catharsis. Catharsis is the process by which a person obtains a release from unpleasant emotional tension by talking about its source. Auditors who listen to what might be considered inconsequential or egocentric talk will likely find the interviewee more willing to share important information. Examples of communication inhibitors include: Competing demands for time. When conflicting demands for time are https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 6 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM present, the interviewee does not necessarily place a negative value on being interviewed, but weighs the value of being interviewed against doing something else. In such circumstances, the auditor must convince the individual that the interview is a good use of time. Threats to ego. In some cases, the interviewee might withhold information because of a perceived threat to his or her self-esteem. Such threats might be internal (e.g., repression of information that does not conform to the individual’s values or expectations), or the interviewee might fear the disapproval of the auditor or others. Etiquette. An etiquette barrier occurs when providing an answer could be perceived by the interviewee as inappropriate (i.e., he or she believes that answering candidly would be considered in poor taste or evidence of a lack of proper etiquette). Often, etiquette considerations can be avoided by selecting the appropriate interviewer and setting for the interview. Trauma. Trauma is common when talking to victims of crimes or other stressful events. The unpleasant feeling is often brought to the surface when the individual recounts the traumatic experience. Auditors must be particularly sensitive in how they handle such circumstances during interviews. Forgetfulness. The inability to recall certain information is a much more frequent obstacle than most interviewers expect. Three primary factors contribute to recollection of an event: the event’s original emotional impact, the time that has elapsed since the event, and the nature of the interview situation. Knowledge of these factors can help the interviewer anticipate potential problems. James Ratley James Ratley, CFE, is president and CEO of the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in Austin, Texas. Copyright © 2019 The Institute of Internal Auditors. All rights reserved. | Privacy Policy https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer Page 7 of 8 2013 Become a Better Interviewer https://iaonline.theiia.org/become-a-better-interviewer 8/7/19, 4)08 PM Page 8 of 8