Factors affecting consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit product: Empirical study in the Malaysian market by Farzana Quoquab, Sara Pahlevan, Jihad Mohammad, Ramayah Thurasamy.

advertisement

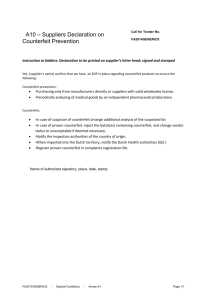

Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics Factors affecting consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit product: Empirical study in the Malaysian market Farzana Quoquab, Sara Pahlevan, Jihad Mohammad, Ramayah Thurasamy, Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Article information: To cite this document: Farzana Quoquab, Sara Pahlevan, Jihad Mohammad, Ramayah Thurasamy, (2017) "Factors affecting consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit product: Empirical study in the Malaysian market", Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 29 Issue: 4, pp.837-853, https:// doi.org/10.1108/APJML-09-2016-0169 Permanent link to this document: https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-09-2016-0169 Downloaded on: 13 September 2017, At: 09:44 (PT) References: this document contains references to 83 other documents. To copy this document: permissions@emeraldinsight.com The fulltext of this document has been downloaded 81 times since 2017* Users who downloaded this article also downloaded: (2016),"Consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit sporting goods in Singapore and Taiwan", Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 28 Iss 1 pp. 23-36 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/ APJML-02-2015-0031">https://doi.org/10.1108/APJML-02-2015-0031</a> (2017),"Predictors of purchase intention toward green apparel products: A cross-cultural investigation in the USA and China", Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management: An International Journal, Vol. 21 Iss 1 pp. 70-87 <a href="https://doi.org/10.1108/JFMM-07-2014-0057">https://doi.org/10.1108/ JFMM-07-2014-0057</a> Access to this document was granted through an Emerald subscription provided by Token:Eprints:V3SDE2MAYIN5DVSETNZG: For Authors If you would like to write for this, or any other Emerald publication, then please use our Emerald for Authors service information about how to choose which publication to write for and submission guidelines are available for all. Please visit www.emeraldinsight.com/authors for more information. About Emerald www.emeraldinsight.com Emerald is a global publisher linking research and practice to the benefit of society. The company manages a portfolio of more than 290 journals and over 2,350 books and book series volumes, as well as providing an extensive range of online products and additional customer resources and services. Emerald is both COUNTER 4 and TRANSFER compliant. The organization is a partner of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) and also works with Portico and the LOCKSS initiative for digital archive preservation. *Related content and download information correct at time of download. The current issue and full text archive of this journal is available on Emerald Insight at: www.emeraldinsight.com/1355-5855.htm Factors affecting consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit product Empirical study in the Malaysian market Empirical study in the Malaysian market 837 Farzana Quoquab IBS, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Sara Pahlevan and Jihad Mohammad Received 13 September 2016 Revised 8 November 2016 4 December 2016 Accepted 6 December 2016 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) IBS, Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Skudai, Malaysia, and Ramayah Thurasamy Faculty of Management, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Minden, Malaysia Abstract Purpose – Most of the past studies have considered social and personal factors in relation to counterfeit product purchase intention. However, there is a dearth of research that linked ethical aspects with such kind of product purchase intention. Considering this gap, the purpose of this paper is to investigate the direct as well as indirect effect of ethical aspects on the attitude of consumers’ counterfeit product purchase in the Malaysian market. Design/methodology/approach – A total of 737 questionnaires were distributed in China Town, Low Yat Plaza, as well as a few “pasar malam” (night markets), which yielded 400 completed usable responses. Partial Least Square Smart PLS software and SPSS were utilised in order to analyse the data. Findings – The results revealed that the ethical aspect in term of religiosity, ethical concern, and perception of lawfulness directly and indirectly affect consumers’ behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit products. Practical implications – It is expected that the study findings will enhance the understanding of marketers as well as policymakers about consumers’ purchase intention of such fake products. Eventually, it will help them to come up with better marketing strategies to purchase counterfeit products and to encourage them to purchase the original product. Originality/value – This is relatively a pioneer study that examines the effect of ethical aspects of consumers in term of their religiosity, ethical concern, and perception of lawfulness on their attitude towards buying counterfeit products. Additionally, this study examines the mediating role of consumer attitude to purchase counterfeit product between ethical aspects and behavioural intention, which is comparatively new to the existing body of knowledge. Last, but not the least, this research has examined these relationships in a new research context i.e., Malaysian market, which can advance the knowledge about consumer behaviour in the East Asian context. Keywords Counterfeit product purchase, Ethical concern, Lawfulness, Malaysian consumers, Religiously Paper type Research paper Introduction In recent years, counterfeit product purchase became a global issue due to its threat to the global economy, as well as to the social and cultural aspect. Counterfeit products are unauthorised products that use other registered goods’ trademark (Chaudhry and Zimmerman, 2009). Counterfeit products can be categorised into different aspects, such as CDs and DVDs, watches and accessories, shoes and handbags, clothes, electronic products, medicines, textiles, and pesticides Chaudhry and Zimmerman (2009). Such fake products abuse the high brand value, logo, package, and trademark of the original brand. The International Chamber of Commerce reported that by adding the amount of pirated digital instruments to counterfeit goods, the sum was worth $650 billion in 2008 alone (Marcelo, 2011). Furthermore, research conducted by The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) (2009) showed that international counterfeit products’ value will increase to $1.7 trillion by 2016, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics Vol. 29 No. 4, 2017 pp. 837-853 © Emerald Publishing Limited 1355-5855 DOI 10.1108/APJML-09-2016-0169 APJML 29,4 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) 838 which is equal to 2 per cent of the current global economic output. Moreover, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, 2009) estimated that the counterfeit market’s value is 5 to 7 per cent of the global trade. Another negative impact of counterfeit products is the unemployment rate which is associated with missing tax revenues. The unemployment cost, missing taxes revenue, and welfare spending due to counterfeit trade was $125 billion in developed countries. Statistics from the US Chamber of Commerce in 2006 mentioned that more than 750,000 individuals were unemployed due to the counterfeit product business (Marcelo, 2011). Considering threatening impact on the global economy and sociocultural aspects, the counterfeit product purchase phenomenon received significant research attention (see Kassim et al., 2016; Tang et al., 2014). Therefore, the present study attempts to investigate the factors that can influence customers’ purchase intention towards counterfeit products in the Malaysian market. Although the sales and purchase of counterfeit products became a global issue, the reasons for consumers’ behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit product is not fully uncovered yet. Most of the prior studies examined the counterfeit product purchase intention in relation to social factors as well personal factors (Cheng et al., 2011). However, there is a dearth of studies that have examined this phenomenon in relation to religiosity and consumers’ ethical concern. It was argued that religious people tend to be more cautious regarding the cost, price, and quality effectiveness of counterfeit products compared to less religious individuals (Vida et al., 2012). In another study, Vitell and Paolillo (2003) indicated that intrinsic religiosity could affect personal belief significantly. Again, it was also suggested that individual tend to support moral philosophies that are idealistic rather than relativistic (Forsyth et al., 2008). In another study, Casidy et al. (2016a, b) found significant differences between religious and less religious individuals in terms of their attitude towards digital piracy. Therefore, it is expected that religiosity, ethical concern, and perception towards lawfulness can be considered as the drivers of consumers’ counterfeit product purchase intention. It is reported that China, Thailand, India and Malaysia are named as “Home for piracy” and “world’s worst violator of intellectual property rights and worst counterfeit offender” (Haque et al., 2009). Havoscope Global Market Index study (2010) shows that, in Malaysia counterfeit product value has increased to RM 378 million by recent years. On the other hand, Congressional International Anti-Piracy “Top 10 Copyright Piracy Nations” meeting announced Malaysia as “precedence copyright fake watch list for extra scrutiny to seize the counterfeit products” (Top 10 Copyright Piracy Nations, 2010). However, Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs Ministry has taken serious steps in order to increase the awareness about fake products through main media and advertisements. But demand of counterfeit products did not change which is a big threat for Malaysian economy. Considering this, the present study aims to predict the direct and indirect effects of religiosity, ethical concern, and attitude towards lawfulness in relation to consumers’ attitude towards buying counterfeit products. The rest of the paper is organised as follows. First, relevant literature is reviewed and the conceptual framework is developed. Next, the adopted methodology is discussed followed by the results, findings, and discussion. Lastly, a conclusion is made and implications, limitations, and future research directions are highlighted. Theoretical framework and hypotheses development Counterfeit products Counterfeit goods are unauthorised products with low quality and standards that the original producer did not manufacture (Nordin, 2009; Staake et al., 2009). These kind of fake products affect authorised companies’ products by decreasing their profit, devaluing their R&D research, and incurring legal fees (Nash, 1989). The range of product categories that were counterfeited has also shifted from luxury goods as practiced a few decades ago to all kinds of consumer goods, including not only software, music, spare parts for vehicles and Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) aircraft, cosmetics, razor blades, washing powder, and clothes, but also food and pharmaceuticals, DVDs, CDs, electronic devices, textiles, military items, wine, cigarettes, pesticides, and fertilisers (Mohamed, 2012). The present study focusses on fashion and electronic devices. This is because the purchase of counterfeit electronics devices has increased significantly in the last decade (Haque et al., 2009; Taylor et al., 2009). Moreover, fashion has the highest rank of being counterfeited. There are different qualities in the counterfeiting of designer brands in the fashion industry. Most of the time, the purpose is only to fool the unsuspecting buyer who only sees what is written on the label, but there are occasions in which the forger tries to imitate the details for which the particular designer is famous (Nordin, 2009; Yoo and Lee, 2009). It is common knowledge among forgers that the buyer does not really care about the originality, but only wants to buy branded-looking products with comparatively cheap price (Hidayat and Diwasasri, 2013). According to Prendergast et al. (2002), counterfeiting is classified into two main categories: deceptive (when a consumer is not aware of buying unauthorised and fake goods and he/she thinks that the product is original), and non-deceptive (when consumers purchase counterfeit goods intentionally and knowingly). In the first type of counterfeiting, the consumer cannot be included for measuring behaviour and attitude towards buying counterfeit goods because the consumer is not aware about the fact (Bian and Moutinho, 2011). Therefore, for the present study, the non-deceptive counterfeiting issue is considered. In the East Asian Region, Malaysia is one of the countries that have a high potential risk for producing, exporting, and selling counterfeit products. The counterfeit product business is a significant threat to Malaysia due to its economic and unemployment rate. By considering its bad impact, the domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs Ministry of Malaysia has attempted to control counterfeit products by implementing and enforcing strict rules and regulation. For example, if the police arrests a seller who is selling unlicensed software, he/she has to pay a fine of 10,000 Malaysian Ringgit or face a sentence of up to five years in jail, or both. Despite knowing the low quality and danger of using counterfeit products, there are still high demands for counterfeit products among the consumer (Albers-Miller, 1999). Therefore, it is pivotal to understand consumers’ attitude as well as behavioural intention towards buying counterfeit products in the Malaysian market. Consumer’s attitude and behavioural intention towards counterfeit products Attitude is a learned predisposition to behave in a consistently favourable or unfavourable manner with respect to a given object (Ajzen, 1991). In general, the relationship between attitude and behavioural intention can be supported theoretically by the Theory of Planned Behaviour (TPB) (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980). According to this theory, attitude is correlated with an individual’s intentions, thus it could be a predictor to estimate the behaviour (Ajzen, 1991; Phau et al., 2015). Following this norm, the present study assumes that when the attitude towards counterfeit product is favourable, it is likely that a person will buy counterfeit products; however, if the attitude towards counterfeit products is unfavourable, the person may not buy counterfeit products. This relationship is verified in many studies in various disciplines (Chiu and Leng, 2016; Jee and Ernest, 2013; Allameh et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2012). Nevertheless, there is a dearth of studies that has examined this relationship in an Asian context, such as Malaysia. Therefore, the present study assumes that a consumer who has a favourable attitude towards counterfeits ( fashion and electronic devise) is more likely to buy it. Based on this assumption, the following hypothesis was developed: H1. Consumers’ attitude towards purchase of counterfeit product will be positively related to his/her behavioural intention. Empirical study in the Malaysian market 839 APJML 29,4 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) 840 Antecedent of consumers’ attitude toward buying counterfeit products Ajzen and Fishbein (1975) are the ones who have suggested a positive direct link between attitude and behaviour. The theory advocates that beliefs affect attitude which in turn affect intention. Various beliefs have been developed around counterfeit products that influence the attitude towards these products For example, social factors, personal factors, and product factors (Phau et al., 2009; Riquelme et al., 2012; Tom et al., 1998; Wong and Ahuvia, 1998). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of studies that examined the effect of ethical aspects on consumers’ attitude towards purchasing counterfeit product. As such, the current study focusses on addressing this gap in the literature. The ethics of buyers could be known as moral rules, standards and principals that lead individual behaviour in the purchase, selection, usage, sales of goods and services (Vitell and Muncy, 1992). For this study, three kinds of ethical aspects were considered: religiosity, ethical concern, and consumer’s perception towards lawfulness. Religiosity Worthington et al. (2003) defined religiosity as individual’s adherence to his/her religious’ beliefs, values and practices and to which extent he/she uses them in every aspect of his/her life. Religiosity is considered an important personal aspect based on the model pioneered by Hunt and Vitell (1993). In this model, religiosity is assumed to have impact on the ethical beliefs of consumers in a positive manner. It implies that the ones who have higher spirituality/religiosity are likely to be more ethical in relation to their ideas and beliefs. It is evident that religion has a key ethical role in contemporary living (Graafland, 2015). Indeed, all of the deity’s laws are considered to be pure, which forms the whole life of a person. Faith instead of reason, secular knowledge and institution are the basics of moral life in all religions (Shukor and Jamal, 2013). Giorgi and Marsh (1990) demonstrated that both religion and the degree of an individual’s religious fervour have a positive impact on their personal ethics. Moreover, McCabe and Trevino (1993) noted that unethical behaviour is negatively related to severity for penalties, such as the ones in the hereafter. Therefore, fear of God’s punishment in life and afterlife causes religious people to maintain morality and virtue. Again, Kennedy and Lawton (1998) identified a negative relation between religion and desire to do unethical actions (Vitell et al., 1993). Therefore, it is expected that fear of God’s punishment prevents individuals in this life from choosing an unethical path. Based on this assumption, the present study proposes that religiosity is negatively related to consumer attitude toward buying counterfeit products. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed: H2. Religiosity will be negatively related to consumers’ attitude towards purchasing counterfeit products. Ethical concern The notion of ethics could be mentioned as principles, moral rules, or the standards that guide the behaviour of a group or person in the purchase, selection, selling and use of services or products (Riquelme et al., 2012; Vitell et al., 1993; Vitell and Paolillo, 2003). An individual’s ethical concern helps decrease unethical behaviour by considering the ethical aspect. It is a value that a person possesses and could be interpreted to be the enduring idea (Schwartz, 2001). It can be defined as the degree to which the buyers believe the questionable behaviours are not wrong or wrong, or unethical and ethical (Vitell and Muncy, 1992). Individual’s ethical concerns in business arebeing studied since 1970s (Wilkes, 1978). However, the ethical aspect of consumer behaviour has not received significant research attention. Based on a different level of ethical concern, different individuals perceive the same act differently. For example, in one study, it is reported that some consumers do not Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) find buying counterfeit products to be unethical (Lysonski and Durvasula, 2008). Contrastingly, Swami et al. (2009) found that older respondents were highly concerned and had less intention to buy counterfeits compared to younger individuals. For the present study, it is assumed that if an individual holds a high level of ethic related to idealism, he/she will realise that purchasing counterfeit products is a wrong doing. Considering this, the following hypothesis was developed: Empirical study in the Malaysian market H3. Ethical concern will be negatively related to consumers’ attitude towards purchasing counterfeit products. 841 Perception towards lawfulness Individual’s perception towards lawfulness is linked with his/her moral rules, standards, and principals that lead the behaviour of an individual and/or group to purchase, select, use, and sell goods and services (Phau et al., 2009). According to Kohlberg (1976), consumers’ personal behaviour is the function of their sense of subjective justice. This means, the higher the level of a person’s moral judgment, the lesser that person will conduct unethical behaviour for personal gain or for business purposes. In regard to counterfeit product purchasing, it is assumed that if a consumer’s perception towards lawfulness is high, then there is a possibility that he/she will exert a negative attitude towards buying the counterfeit brands of luxury goods (Phau et al., 2009). Conversely, if the consumer’s perception towards lawfulness is not strong enough, he/she will tend to buy the counterfeit brands of luxury goods. Therefore, the following hypothesis is developed: H4. Consumer’s perception towards lawfulness will be negatively related to consumers’ attitude towards purchasing counterfeit products. Mediating role of attitude The proposed mediating role of attitude can be justified based on Ajzen’s and Fishbein (1975) theory. According to this theory, beliefs influence attitude that in turn affect intention. If consumer has positive beliefs about counterfeit products he/she is likely to develop favourable attitudes towards counterfeits. As consequences there are more chances to form favourable intention to purchase the counterfeit goods. Conversely, if the consumer holds negative beliefs about this type of product, he/she is more inclined to develop unfavourable attitudes. In each instance there are fewer chances to form favourable intention to purchase the counterfeit goods. Beside theoretical justification empirical, evidences also exist. For example, past studies found that attitude towards buying counterfeit products mediate the relationship between social, personal, and product factors and consumer intention to purchase counterfeit products (Ang et al., 2001; Bian and Moutinho, 2009; Chaudhry and Stumpf, 2011; Phau et al., 2009). Nevertheless, there is a paucity of research that has examined the mediating role of attitude between ethical aspects and consumer intention to purchase counterfeit products. Therefore, the following hypotheses are developed: H5. Attitude toward buying counterfeit products mediate the relationship between religiosity and consumer’s intention to purchase counterfeit product. H6. Attitude toward buying counterfeit products mediates the relationship between ethical concern and consumer’s intention to purchase counterfeit product. H7. Attitude toward buying counterfeit products mediates the relationship between perception toward lawfulness and consumer’s intention to purchase counterfeit product. APJML 29,4 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) 842 Conceptual framework The proposed relationships among the study variables are shown in Figure 1. Methodology Measurement of the variables All scales to measure the study variables were borrowed from past literature (see Appendix). Behavioural intention was measured by using a five-item scale adapted from Zeithaml et al. (1996), whereas attitude was borrowed from Phau et al. (2009). The religiosity was measured by using five items adapted from Shukor and Jamal (2013). This scale was developed at two stages: first, qualitative data were collected using face-to-face interview; and second, a quantitative data was collected using a survey questionnaire. The findings of this study revealed that religiosity can be measured as unidimensional construct that consist of five items. This scale found to be valid and reliable and can be used by consumer researchers. Contrastingly, ethical concern and perception toward lawfulness scales were borrowed from Chaudhry and Stumpf (2011) and Lichtenstein et al. (1990), rrespectively. All scales are showed in Table AI. A seven-point Likert scale was utilised, which ranged from 1 ¼ “strongly disagree” to 7 ¼ “strongly agree”. Study location The primary data for this study were obtained through the questionnaire survey. This study focussed on two major categories of counterfeit products, i.e., fashion and electronic devices. The study was carried in China Town or alternatively known as, “Paradise of fake products” (named by tourists), Low Yat Plaza; and a variety of local markets (pasar malam or night market, day market, etc.). In these markets, one can find plenty of branded and also pirated footwear, bags, clothes, toys, accessories, watches, and electronic devices. Data collection procedure Since it was difficult to get a list of all elements of the population, non-probability sampling more specifically judgmental sampling was employed. Using this type of sampling is a good choice because it permits a theoretical generalisation of the findings (Calder et al., 1981; Mohammad et al., 2010). With respect to sample size, Churchill (1991) contended that the number of surveys in a regional consumer study should range between 200-500 responses. Since this study chose individual as the sampling unit, the sample size was needed to fall within that range. Therefore, obtaining 400 valid questionnaires would be sufficient to analyse the data. Additionally, respondents were required to be at least 18 years old since this group is sufficiently knowledgeable to make decisions and have purchasing power (Norzalita et al., 2009). Moreover, it is expected that respondents who are 18 years old are well informed about counterfeit products in different ways, such as media, friends, Ethical aspect: • Religiosity (RE) • Ethical concern (EC) Figure 1. Proposed conceptual framework • Attitude towards lawfulness (ATL) Attitude towards buying counterfeit products (ATT) Behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit products (INT) advertismnet, etc. In total, 737 questionnaires were distributed, in which 450 questionnaires were returned and finally, 400 valid questionnaires were found usable for further analysis. SPSS version 21 and SmartPLS 3 were utilised to run the analysis. Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Profile of the respondents As shown in Table I, the male frequency is 199 or 49.8 per cent of the total, while female frequency is 201 or 50.2 per cent. The minimum frequency from the total 400 respondents is equal to 32, and relevant to the age group of 56 and higher. In addition, the highest level of frequency was 128 for the group aged from 26 to 35. The next question of demographics is for the educational background according to six different groups. The minimum level of frequency from the total 400 participants is 10 from the doctorates. In addition, the highest level of frequency is 125 from the diploma/technical school certificate group. Empirical study in the Malaysian market 843 Result SmartPLS 3.0 software was used (Ringle et al., 2015) to analyse the model developed. Following the recommended two-stage analytical procedures by Anderson and Gerbing (1988), Number of respondents (N ¼ 400) % Gender Male Female 199 201 49.8 50.2 Age Below 25 26-35 36-45 46-55 56 and above 80 128 104 56 32 20.0 32.0 26.0 14.0 8.0 Ethnicity Malay Chinese Indian Others 201 123 53 23 50.2 30.8 13.2 5.8 Marital status Single Married Divorced Widow/widower 168 203 22 7 42.0 50.8 5.5 1.8 Educational background Primary school certificate Secondary school certificate Diploma/technical school certificate Bachelor degree or equivalent Master degree Doctoral degree 75 83 125 81 26 10 18.8 20.8 31.2 20.2 6.5 2.5 Income Below 2,000 2,001-3,000 3,001-4,000 4,001-5,000 Above 5,001 65 126 108 67 34 16.2 31.5 27.0 16.8 8.5 Demographics Table I. Demographic profile of the respondents APJML 29,4 844 this study tested the measurement model and the structural model (see Hair et al., 2014; Mohammad et al., 2015; Ramayah et al., 2013). In order to test the significance of the path coefficients and the loadings, a bootstrapping (resampling ¼ 5,000) method was used (Chua et al., 2016; Hair et al., 2014). Common method variance needs to be examined when data are collected via self-reported questionnaires and in particular, both the predictor and criterion variables are obtained from the same person (Podsakoff et al., 2003). Harman’s single factor test was used, whereby all items are loaded in a factor analysis and if one factor emerges explaining the majority of the variance, then common method variance exist. Our analysis returned a 5-factor solution ( χ2 ¼ 25,679.91, po0.01) explaining a total variance of 73.107 per cent. The first factor only captured 32.32 per cent variance, thus we can conclude that method variance is not a serious problem in this study. Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Measurement model First, convergent validity was confirmed when the loadings (W0.70), composite reliability (W 0.7) and average variance extracted ( W0.5) as suggested by Hair et al. (2014) and as shown in Table II were achieved. Next, discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell and Larcker (1981) method, which requires the square root of the variance extracted to be higher than the correlations. This was also achieved in Table II. Therefore, with these two tests, we have shown that the measures in this study have sufficient convergent and discriminant validity. Structural model Assessing the structural model involves evaluating R2, β, and the corresponding t-values with predictive relevance (Q2) (Hair et al., 2014; Mohammad et al., 2016). The R2 of attitude was 0.508, i.e. all of the predictors explained 50.8 per cent of the variance in attitude, whereas Intention had an R2 of 0.685, which indicates that attitude can explain 68.5 per cent of the variance in intention. First we looked at the predictors of attitude, religiosity ( β ¼ −0.225, p o0.01), ethical concern ( β ¼ −0.220, po 0.01), and perception towards lawfulness ( β ¼ −0.212, p o0.01) were negatively related to attitude. Attitude was positively ( β ¼ 0.525, p o0.01) related to intention to purchase. Therefore, H1, H2, H3, H4, were supported. Next we looked at the mediation effect of attitude on the IV-DV relationship. Religiosity → attitude → intention ( β ¼ −0.118, p o 0.01, BC0.95 LL ¼ −0.0189 and UL ¼ −0.043), ethical concern → attitude → intention ( β ¼ −0.116, p o 0.01, BC0.95 LL ¼ −0.165 and UL ¼ −0.046) and perception towards lawfulness → attitude → intention ( β ¼ −0.111, po 0.01, BC0.95 LL ¼ −0.190 and UL ¼ −0.042) were significantly mediated by attitude. Moreover, as suggested by Preacher and Hayes (2004, 2008), the indirect effects did not straddle a 0 in between, indicating that there is mediation. Therefore, we can conclude Mean Table II. Descriptive, convergent and discriminant validity of measures 1. ATL 2. ATT 3. EC 4. INT 5. RE Note: Values SD AVE CR 3.73 1.39 0.67 0.89 4.43 1.09 0.51 0.86 3.69 1.31 0.70 0.87 3.94 1.39 0.68 0.91 3.78 1.46 0.74 0.85 in the diagonal italicized are square root of 1 2 3 4 5 0.82 0.66 0.71 0.81 0.56 0.83 0.62 0.52 0.50 0.82 0.8 0.62 0.76 0.60 0.86 AVE while the offdiagonals are correlations Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) that the mediation effect is statistically significant, indicating that H5, H6, H7, were supported (Table III). Hair et al. (2014) suggested that the blindfolding procedure should only be applied to endogenous constructs that have a reflective measurement (multiple items or single item). If the Q2 value is larger than 0, the model has predictive relevance for a certain endogenous construct and otherwise if the value is less than 0 (Hair et al., 2014; Fornell and Cha, 1994). In this study we can see that all of the Q2 values are more than 0 for attitude (Q2 ¼ 0.325) and intention (Q2 ¼ 0.167), suggesting that the model has sufficient predictive relevance. Empirical study in the Malaysian market 845 Discussion The objective of this study was to investigate the factors that affect consumers’ attitude and behavioural intention towards purchasing counterfeit products in the Malaysian counterfeit market. To address this crucial matter, a research model based on the TPB was developed to provide a more comprehensive understanding about the effect of ethical aspects on consumer intention to purchase counterfeit products. Additionally, the relationship between attitude and behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit products was also examined. From the results, the ethical beliefs that impact attitudes towards counterfeits among Malaysian consumers who have purchased counterfeits are: religiously, ethical concern, and attitude toward lawfulness. Overall, the findings of this research indicate that all hypotheses were supported, and were consistent with the findings of other studies regarding counterfeit products using TPB (Hernan et al., 2012; Perez et al., 2010). Moreover, the predictors of consumer attitude to purchase counterfeit product explained 0.508 per cent of the variance, while the predictor of behavioural intention explained 0.685 per cent of the variance. In explaining hypotheses, data demonstrated supports for the link between beliefs, attitudes, and behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit products, which is consistent with TPB and past studies (Ajzen and Fishbein, 1980; Phau et al., 2014). It implies that consumers’ attitude towards buying counterfeit products is an important factor that has significant and positive impact on behavioural intention to purchase. In the context of counterfeits, it is expected that consumers with a more favourable attitude toward buying counterfeit products will have more favourable behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit goods. This study hypothesised that the ethical aspect in terms of religiosity, ethical concern, and perception towards lawfulness to be the antecedents of consumers’ attitude toward purchasing counterfeit products. The finding demonstrated that all of these aspects have a significant negative relation on consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit product. In other words, the higher the level of an individual’s moral judgment, a consumer is less likely to purchase the counterfeit product. This is in line with the TPB. This theory assumes that individuals’ attitude towards a certain behaviour depends on his/her beliefs. More clearly, religious and ethical individuals are more likely to restrain themselves from performing any action that is Hypothesis Relationship Std β SE t-value Decision BC 95% LL BC 95% UL H1 Attitude → intention H2 Religiosity → attitude H3 EC → attitude H4 ATL → attitude H5 Religiosity → Attitude → intention H6 EC → attitude → intention H7 ATL → Attitude → intention Notes: *p o0.05; **p o 0.01 0.52 −0.22 −0.22 −0.21 −0.11 −0.11 −0.11 0.03 13.35** Supported 0.06 3.34** Supported 0.05 3.94** Supported 0.06 3.09** Supported 0.03 3.17** Supported 0.02 3.99** Supported 0.03 2.92** Supported 0.46 0.07 0.31 0.09 0.18 0.16 0.19 0.61 0.32 0.08 0.36 0.04 0.04 0.04 Table III. Hypotheses testing APJML 29,4 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) 846 against their principles. Furthermore, the result of this study is in agreement with past studies that found religious and ethical people to be more motivated to show positive and ethical behaviour in terms of citizenship behaviour, commitment, satisfaction, and avoiding unethical products and services, such as counterfeit products, drugs, alcohol, night clubs, etc. (see Cohen and Johnson, 2016; Giorgi and Marsh, 1990; Mohammad et al., 2015; Osafo et al., 2013; Sawatzky et al., 2009; Tan, 2002; Tufail et al., 2016). The ethical aspect works as the moral rules, standards, and principals that lead individual behaviour or a group in the purchase, selection, usage, and sales of goods and services (Vitell and Muncy, 1992). As suggested by Hunt and Vitell (1986, 1993), spirituality/religiosity is an important aspect that held on the ethical beliefs of consumers in a positive approach. It indicates that the ones who hold higher spirituality/religiosity may be more ethical in relation to purchasing counterfeit products. A possible explanation for this result can be due to the fact that religious and ethical individuals have constructive views and opinions that influence their attitudes positively in terms of love, respect, appreciation, and fear of God, society, and law. These feelings restrain them from committing unethical behaviour, such as lying, cheating, and/or promoting, buying, and using illegal products and/or services. It was also found that consumers’ attitude mediates the relationship between personal aspects, ethical concern and consumers’ intention. This is consistent with the TPB, which postulated that intention always mediates the relationship between attitude and behaviour. The result was also in line with past studies that confirmed that behavioural intention can mediate the relationship between attitude and actual behaviour (see Riquelme et al., 2012; Chua et al., 2016). More particularly, religious, and ethical consumers are inclined to develop a negative attitude about the counterfeit products since it is against and contradicts their values and beliefs, and ultimately, they will not purchase these types of fake products. Theoretical and practical contribution This study contributes significantly to the theory and practice alike. Theoretically, this study has developed relatively new linkages, i.e. the effect of religiosity, ethical concern, and lawfulness on consumer attitude to purchase counterfeit products. Additionally, this is a comparatively new study that tested the mediating role of consumer attitude between ethical aspects and behavioural intention to purchase counterfeit products. This is likely to contribute significantly to the theory of consumer behaviour regarding the consumption of these types of goods in a non-western context. Most importantly, this study contributed to the TPB by incorporating ethical beliefs as antecedent of consumer attitude. Past studies focussed on three types of beliefs, i.e., normative beliefs, behavioural beliefs, and control beliefs and less attention was given to ethical beliefs. Practically, this study has tested the direct and indirect relationships in a new research context, i.e., Malaysian counterfeit market. The output of this study emphasised on the crucial role of ethical aspects in preventing a consumer from purchasing these types of fake products that can have a harmful effect on individuals, groups, and all nations socially and economically. Religious organisations in Malaysia, such as mosques, churches, and temples are encouraged to practice their main duties in inculcating and cultivating the religious values and beliefs that stress on implementing and practicing ethical behaviour, as well as avoiding unethical deeds. Moreover, government, legislators, and decision makers in Malaysia are recommended strongly to instil the ethical values, beliefs, and behaviour through the education system at the school, college, and university level, to ensure better behaviour from the current and future generations that can enhance, improve, and advance the quality of life in Malaysia. Additionally, conferences, seminars, and public talks can be organised by private and public organisations to address this phenomenon and to come up with some strategies that can help to control and minimise its effects. Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Conclusion Currently, counterfeit products are an important global issue because counterfeit and pirated products are not only a threat to the global economy, as well as social and cultural welfare, but are also harmful and dangerous to those who are not able to differentiate the fake from the original. Increasing counterfeit products in the international trade market has led to different problems around the world, and this issue is more significant because counterfeit products have shifted from simple items, such as shoes and handbags to chemical products, such as medicines and pesticides. In this instance, the present study investigates the factors that affect consumers’ attitude and behavioural intention towards buying counterfeit products. It is hoped that both academicians and practitioners can benefit from this study finding. As mentioned before, even with awareness of all the issues related to using unauthorised goods, the number of consumers of counterfeit products is rising around the world. It is expected that this study would help the original marketers to have a better understanding of the consumers’ needs and wants, which will eventually help them to better strategize their marketing efforts. Although the present study has its merits in regard to testing reasonably new linkages and to providing some useful findings regarding this issue, it is not beyond of some limitations. However, the limitations of this study may serve as the future research directions for other studies in the field. As suggestions for future studies, one could test the model presented here in different product categories (such as CDs, DVDs, food, toys, etc.) and examine for possible differences. It is also recommended that other variables can be included in the model as moderator, such as consumer involvement with the product, gender and ethnicity. This is because when consumers are more involved with the product, he/she should be more worried about the buying decision and have a higher risk aversion. In a nutshell, this study opens up the avenue for future researchers and calls for more relevant studies to be conducted in this field. References Ajzen, I. (1991), “The theory of planned behaviour”, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, Vol. 50 No. 2, pp. 179-211. Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1975), Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research, Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA. Ajzen, I. and Fishbein, M. (1980), Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ. Albers-Miller, N.D. (1999), “Consumer misbehavior: why people buy illicit goods”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 16 No. 3, pp. 273-287. Allameh, S.M., Pool, J.K., Jaberi, A., Salehzadeh, R. and Asadi, H. (2015), “Factors influencing sport tourists’ revisit intentions: the role and effect of destination image, perceived quality, perceived value and satisfaction”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 27 No. 2, pp. 191-207. Anderson, J.C. and Gerbing, D.W. (1988), “Structural equation modeling in practice: a review and recommended two step approach”, Psychological Bulletin, Vol. 103 No. 3, pp. 411-423. Ang, S.H., Cheng, P.S., Lim, E.A. and Tambyah, S.K. (2001), “Spot the difference: consumer responses towards counterfeits”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 18 No. 3, pp. 219-235. Bian, X. and Moutinho, L. (2009), “An investigation of determinants of counterfeit purchase consideration”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 62 No. 3, pp. 368-378. Bian, X. and Moutinho, L. (2011), “Counterfeits and branded products: effects of counterfeit ownership”, Journal of Product & Brand Management, Vol. 20 No. 5, pp. 379-393. Empirical study in the Malaysian market 847 APJML 29,4 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) 848 Calder, B.J., Phillips, L.W. and Tybout, A.M. (1981), “Designing research for application”, Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 197-207. Casidy, R., Phau, I. and Lwin, M. (2016a), “Religiosity and digital piracy: an empirical examination”, Services Marketing Quarterly, Vol. 37 No. 1, pp. 1-13. Casidy, R., Phau, I. and Lwin, M. (2016b), “The role of religious leaders on digital piracy attitude and intention”, Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, Vol. 32, September, pp. 244-252. Chaudhry, P.E. and Zimmerman, A. (2009), The Economics of Counterfeit Trade: Governments Consumers, Pirates and Intellectual Property Rights, Springer Science & Business Media, Heidelberg. Chaudhry, P.E. and Stumpf, S.A. (2011), “Consumer complicity with counterfeit products”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 139-151. Cheng, S., Fu, H.-H. and Tu, L.T.C. (2011), “Examining customer purchase intentions for counterfeit products based on a modified theory of planned behavior”, International Journal of Humanities and Social Science, Vol. 1 No. 10, pp. 278-284. Chiu, W. and Leng, H.K. (2016), “Consumers’ intention to purchase counterfeit sporting goods in Singapore and Taiwan”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 28 No. 1, pp. 23-36. Chua, K.B., Quoquab, F., Mohammad, J. and Basiruddin, R. (2016), “The mediating role of new ecological paradigm between value orientations and pro-environmental personal norm in the agricultural context”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 323-349. Churchill, G.A. Jr (1991), Research Realities in Marketing Research: Methodological Foundation, 5th ed., The Dryden Press, Fort Worth, TX. Cohen, A.B. and Johnson, K.A. (2016), “The Relation between religion and well-being”, Applied Research in Quality of Life, Vol. 11 No. 1, pp. 1-15. Fornell, C. and Cha, J. (1994), “Partial least squares”, in Bagozzi, R.P. (Ed.), Advanced Methods in Marketing Research, Blackwell, Cambridge, pp. 52-78. Fornell, C. and Larcker, D.F. (1981), “Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol 18 No. 1, pp. 39-50. Forsyth, D.R., O’Boyle, E.H. Jr and McDaniel, M.A. (2008), “East meets west: a meta-analytic investigation of cultural variations in idealism and relativism”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 83 No. 4, pp. 813-833. Giorgi, L. and Marsh, C. (1990), “The protestant work ethic as a cultural phenomenon”, European Journal of Social Psychology, Vol. 20 No. 6, pp. 499-517. Graafland, J. (2015), “Religiosity, attitude, and the demand for socially responsible products”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 76 No. 2, pp. 1-18. Hair, J.F., Sarstedt, M. and Hopkins, L. (2014), “Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM): an emerging tool in business research”, European Business Review, Vol. 26 No. 2, pp. 106-112. Haque, A., Khatibi, A. and Rahman, S. (2009), “Factors influencing buying behavior of piracy products and its impact to Malaysian market”, International Review of Business Research Papers, Vol. 5 No. 2, pp. 383-401. Hernan, E.R., Abbas, E.M.S. and Rios, R.E. (2012), “Intention to purchase fake products in an Islamic country”, Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 6-22. Hidayat, A. and Diwasasri, A.H.A. (2013), “Factors influencing attitudes and intention to purchase counterfeit luxury brands among indonesian consumers”, International Journal of Marketing Studies, Vol. 5 No. 4, pp. 144-151. Hunt, S.D. and Vitell, S.J. (1986), “A general theory of marketing ethics”, Journal of Macromarketing, Vol. 6 No. 1, pp. 5-16. Hunt, S.D. and Vitell, S.J. (1993), “The general theory of marketing ethics: a retrospective and revision”, in Smith, N.C. and Quelch, J.A. (Eds), Ethics in Marketing, Irwin, Homewood, IL, pp. 775-784. Jee, T.W. and Ernest, C.R. (2013), “Consumers’ personal values and sales promotion preferences effect on behavioural intention and purchase satisfaction for consumer product”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 25 No. 1, pp. 70-101. Kassim, N., Bogari, N., Salamah, N. and Zain, M. (2016), “The relationships between collective oriented values and materialism, product status signaling and product satisfaction: a two-city study”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 28 No. 5, pp. 765-779. Kennedy, E.J. and Lawton, L. (1998), “Religiousness and business ethics”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 17 No. 2, pp. 163-175. Kohlberg, L. (1976), “Moral stage and moralization: the cognitive-developmental approach”, in Lickona, T. (Ed.), Moral Development and Behavior, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York, NY, pp. 31-53. Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Lichtenstein, D.R., Netemeyer, R.G. and Burton, S. (1990), “Distinguishing coupon proneness from value consciousness: an acquisition-transaction utility theory perspective”, The Journal of Marketing, Vol. 54 No. 3, pp. 54-67. Lysonski, S. and Durvasula, S. (2008), “Digital piracy of MP3s: consumer and ethical predispositions”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 25 No. 3, pp. 167-178. McCabe, D.L. and Trevino, L.K. (1993), “Academic dishonesty: honor codes and other contextual influences”, Journal of Higher Education, Vol. 64, September-October, pp. 522-538. Marcelo, C. (2011), “The crimes of fashion: the effects of trademark and copyright infringement in the fashion industry”, a senior thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University, Spring. Mohammad, J., Habib, F.Q.B. and Alias, M.A.B. (2010), “Organizational justice and organizational citizenship behavior in higher education institution”, Global Business and Management Research, Vol. 2 No. 1, pp. 13-32. Mohammad, J., Quoquab, F., Rahman, N.M.N.A. and Idris, F. (2015), “Organisational citizenship behaviour in the Islamic financial sector”, International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, Vol. 10 No. 1, pp. 1-27. Mohammad, J., Quoquab, F., Makhbul, Z.M. and Ramayah, T. (2016), “Bridging the gap between justice and citizenship behaviour behavior in Asian culture”, Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, Vol. 23 No. 4. Mohamed, K. (2012), “Trademark counterfeiting: comparative legal analysis on enforcement within Malaysia and the United Kingdom and at their borders”, thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of doctor of philosophy in law at Newcastle law school, Newcastle University. Nash, T. (1989), “Only imitation? The rising cost of counterfeiting”, Director, pp. 64-69. Nordin, N. (2009), “A study on consumers’ attitude towards counterfeit products in Malaysia”, unpublished master thesis, Universito Tenaga Nasional, Kuala Lumpur, available at: http:// repository.um.edu.my/846/1/CGA070109.pdf (accessed 13 December 2016). Norzalita, A.A., Yasin, N.M. and Tajuddin, N. (2009), “Antecedents of customer loyalty in the mobile telecommunication services market in Malaysia”, in Salleh, A.H.M., Ariffin, A.A.M., Poon, J.M.L. and Aman, A. (Eds), Services Management and Marketing: Studies in Malaysia, UKM-Graduate School of Business, Bangi, pp. 325-360. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) (2009), “The economic impact of counterfeiting”, available at: www.oecd.org/industry/ind/2090589.pdf (accessed 21 December 2016). Osafo, J., Knizek, B.L., Akotia, C.S. and Hjelmeland, H. (2013), “Influence of religious factors on attitudes towards suicidal behaviour in Ghana”, Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 52 No. 2, pp. 488-504. Perez, M.E., Castaño, R. and Quintanilla, C. (2010), “Constructing identity through the consumption of counterfeit luxury goods”, Qualitative Market Research: An International Journal, Vol. 13 No. 3, pp. 219-235. Empirical study in the Malaysian market 849 APJML 29,4 Phau, I., Sequeira, M. and Dix, S. (2009), “To buy or not to buy a ‘counterfeit’ Ralph Lauren polo shirt: the role of lawfulness and legality toward purchasing counterfeits”, Asia-Pacific Journal of Business Administration, Vol. 1 No. 1, pp. 68-80. Phau, I., Lim, A., Liang, J. and Lwin, M. (2014), “Engaging in digital piracy of movies: a theory of planned behaviour approach”, Internet Research, Vol. 24 No. 2, pp. 246-266. 850 Phau, I., Teah, M. and Chuah, J. (2015), “Consumer attitudes towards luxury fashion apparel made in sweatshops”, Journal of Fashion Marketing and Management, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 169-187. Podsakoff, P.M., MacKenzie, S.B., Lee, J.Y. and Podsakoff, N.P. (2003), “Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies”, Journal of Applied Psychology, Vol. 88 No. 5, pp. 879-903. Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Preacher, K.J. and Hayes, A.F. (2004), “SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models”, Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, Vol. 36 No. 4, pp. 717-731. Preacher, K.J. and Hayes, A.F. (2008), “Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models”, Behavior Research Methods, Vol. 40 No. 3, pp. 879-891. Prendergast, G., Chuen, L.H. and Phau, I. (2002), “Understanding consumer demand for non-deceptive pirated brands”, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, Vol. 20 No. 7, pp. 405-416. Ramayah, T., Yeap, J.A.L. and Ignatius, J. (2013), “An empirical inquiry on knowledge sharing among academicians in higher learning institutions”, Minerva: A Review of Science, Learning and Policy, Vol. 51 No. 2, pp. 131-154. Ringle, C.M., Wende, S. and Will, S. (2015), SmartPLS 3.0 (M3) Beta, University of Hamburg, Hamburg. Riquelme, H.E., Mahdi Sayed Abbas, E. and Rios, R.E. (2012), “Intention to purchase fake products in an Islamic country”, Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, Vol. 5 No. 1, pp. 6-22. Sawatzky, R., Gadermann, A. and Pesut, B. (2009), “An investigation of the relationships between spirituality, health status and quality of life in adolescents”, Applied Research in Quality of Life, Vol. 4 No. 1, pp. 5-22. Schwartz, M. (2001), “The nature of the relationship between corporate codes of ethics and behaviour”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 32 No. 3, pp. 247-262. Shukor, S.A. and Jamal, A. (2013), “Developing scales for measuring religiosity in the context of consumer research”, Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research, Vol. 13 No. 1, pp. 69-74. Staake, T., Thiesse, F. and Fleisch, E. (2009), “The emergence of counterfeit trade: a literature review”, European Journal of Marketing, Vol. 43 Nos 3/4, pp. 320-349. Swami, V., Chamorro-Premuzic, T. and Furnham, A. (2009), “Faking it: personality and individual difference predictors of willingness to buy counterfeit goods”, The Journal of Socio-Economics, Vol. 38 No. 5, pp. 820-825. Tan, B. (2002), “Understanding consumer ethical decision making with respect to purchase of pirated software”, Journal of Consumer Marketing, Vol. 19 No. 2, pp. 96-111. Tang, F., Tian, V. and Zaichkowsky, J. (2014), “Understanding counterfeit consumption”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 26 No. 1, pp. 4-20. Taylor, S.A., Ishida, C. and Wallace, D.W. (2009), “Intention to engage in digital piracy a conceptual model and empirical test”, Journal of Service Research, Vol. 11 No. 3, pp. 246-262. The International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) (2009), “The economic impacts of counterfeiting and piracy – report prepared for BASCAP and INTA”, available at: https://iccwbo.org/publication/ economic-impacts-counterfeiting-piracy-report-prepared-bascap-inta/ (accessed 15 December 2016). Tom, G., Garibaldi, B., Zeng, Y. and Pilcher, J. (1998), “Consumer demand for counterfeit goods”, Psychology & Marketing, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 405-421. Top 10 Copyright (2010), “Top 10 Copyright Piracy Nations”, available at: www.blogtactic.com/2010/05/ top-10-copyright-piracy-nations.html (accessed 1 December 2015). Tufail, U., Ahmad, M.S., Ramayah, T., Jan, F.A. and Shah, I.A. (2016), “Impact of Islamic work ethics on organisational citizenship behaviours among female academic staff: the mediating role of employee engagement”, Applied Research in Quality of Life, Vol 11 No. 4, pp. 1-25. Vida, I., Koklic, M.K., Kukar-Kinney, M. and Penz, E. (2012), “Predicting consumer digital piracy behavior: the role of rationalization and perceived consequences”, Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing, Vol. 6 No. 4, pp. 298-313. Vitell, S.J. and Muncy, J. (1992), “Consumer ethics: an empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgments of the final consumer”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 11 No. 8, pp. 585-597. Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Vitell, S.J., Nwachukwu, S.L. and Barnes, J.H. (1993), “The effects of culture on ethical decision-making: an application of Hofstede’s typology”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 12 No. 10, pp. 753-760. Vitell, S.J. and Paolillo, J.G. (2003), “Consumer ethics: the role of religiosity”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 46 No. 2, pp. 151-162. Wilkes, R.E. (1978), “Fraudulent behavior by consumers”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 42 No. 4, pp. 67-75. Wong, N.Y. and Ahuvia, A.C. (1998), “Personal taste and family face: luxury consumption in Confucian and Western societies”, Psychology and Marketing, Vol. 15 No. 5, pp. 423-441. Worthington, E.L. Jr, Wade, N.G., Hight, T.L., Ripley, J.S., McCullough, M.E., Berry, J.W., Schmitt, M.M., Berry, J.T., Bursley, K.H. and O’connor, L. (2003), “The religious commitment Inventory – 10: development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counselling”, Journal of Counseling Psychology, Vol. 50 No. 1, p. 84. Yang, H.C., Liu, H. and Zhou, L. (2012), “Predicting young Chinese consumers’ mobile viral attitudes, intents and behaviour”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 24 No. 1, pp. 59-77. Yoo, B. and Lee, S.-H. (2009), “Buy genuine luxury fashion products or counterfeits”, Advances in Consumer Research, Vol. 36 No. 1, pp. 280-228. Zeithaml, V.A., Berry, L.L. and Parasuraman, A. (1996), “The behavioral consequences of service quality”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 60 No. 2, pp. 31-46. Further reading Li, J., Mizerski, D., Lee, A. and Liu, F. (2009), “The relationship between attitude and behavior: an empirical study in China”, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 232-242. Muncy, J.A. and Vitell, S.J. (1992), “Consumer e thics: an empirical investigation of factors influencing ethical judgements of the final consumer”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 11 No. 8, pp. 585-597. Ramayah, T., Ai Leen, J.P. and Wahid, N.B. (2002), “Purchase preference and view: the case of counterfeit goods”, The Proceeding of the UBM Conference, pp. 1-13. (The Appendix follows overleaf.) Empirical study in the Malaysian market 851 APJML 29,4 Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) 852 Appendix Ethical concern 1 2 3 4 Counterfeiting infringes on intellectual property rights Counterfeiting damages the original industry Obtaining counterfeit goods is illegal Obtaining counterfeit goods is unethical Religiosity 4 6 7 8 9 I believe in God I carefully avoid shameful acts I always perform my duty to God It is important for me to follow God’s commandments conscientiously Religious beliefs influence all my dealings with everyone Attitude toward lawfulness 10 11 12 13 A person should obey the laws no matter how much they interfere with personal ambitions A person should tell the truth in court, regardless of the consequences A person is justified in giving a false testimony to protect a friend on trial It is all right for a person to break the law if he or she does not get caught Attitude toward buying counterfeit product 14 Generally speaking, counterfeit products have satisfying quality 15 Generally speaking, counterfeit products are practical 16 Generally speaking, counterfeit products are reliable 17 For me, to buy/use counterfeit products is virtue of thrift (economics) 18 For me, to buy/use counterfeit products is convenient 19 For me, to buy/use counterfeit products is wise 20 For me, to buy/use counterfeit products is proud 21 For me, to buy/use counterfeit products is guiltless Table AI. Adapted items to measure the study variables Behavioural intention 22 23 24 25 26 I say positive things about the counterfeit product to other people I recommend counterfeit product to someone who seeks my advice I encourage friends and relatives to buy counterfeit products I consider counterfeit product as my first choice to buy compared to other expensive original product I shall buy more counterfeit products in future About the authors Farzana Quoquab is a Senior Lecturer at the International Business School, UTM. She has received her Doctorate of Business Administration Degree from the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. She has presented papers at international and national conferences and published articles in peer-reviewed international journals such as Economics and Technology Management Review, Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics and Asian Academy of Management Journal. Sara Pahlevan is an MBA Student at the International Business School, UTM. Her focus of the research is consumer behaviour. Jihad Mohammad is a Senior Lecturer at the International Business School, UTM. He has received his DBA Degree from Universiti Kebangsaan, Malaysia. He has presented papers at various international and national conferences and published articles in peer-reviewed international journals. He has versatile career exposure. His current research interest includes organisational citizenship behaviour, work ethics, and consumer behaviour. Jihad Mohammad is the corresponding author and can be contacted at: jihad@ibs.utm.my Downloaded by 210.195.118.220 At 09:44 13 September 2017 (PT) Ramayah Thurasamy is a Professor at the School of Management in USM. He teaches mainly courses in Research Methodology and Business Statistics and has also conducted training courses for the local government (research methods for candidates departing overseas for higher degree, Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam). Apart from teaching, he is an Avid Researcher, especially in the areas of technology management and adoption in business and education. His publications have appeared in Computers in Human Behavior, Resources Conservation and Recycling, Journal of Educational Technology & Society, Direct Marketing: An International Journal, Information Development, Journal of Project Management ( JoPM), Management Research News (MRN), International Journal of Information Management, International Journal of Services and Operations Management (IJSOM), Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management (ECAM) and North American Journal of Psychology. For instructions on how to order reprints of this article, please visit our website: www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/licensing/reprints.htm Or contact us for further details: permissions@emeraldinsight.com Empirical study in the Malaysian market 853