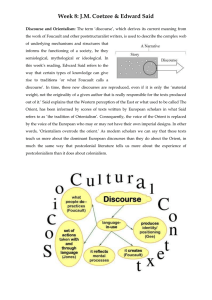

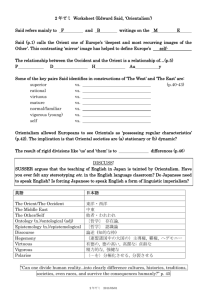

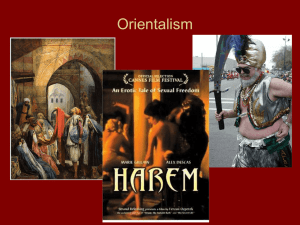

ORIENTALISM. By Edward W. Said. New York: Pantheon Books, 1978. In Orientalism, Edward Said offers a critique of the study of Eastern cultures and the discourse of Orientalism in Western scholarship. Said examines the Baconian themes of knowledge and power, arguing that much of the study of the Orient, or the East, is not objectively represented. Western scholarship asserts the existence and value of Western civilisation and subsequently acts as a justification for "dominating, restricting and having authority over the Orient" (p. 3). Constructed by the ‘Occident', or the West, Orientalism is a discourse in which binary relations of the dominant and fundamentally dissimilar West is different to the East (p.67-68). The history of European colonial rule and political domination of Eastern civilisations has distorted the intellectual objectivity and cultural representations of Western authors (p. 32). To Said, the history of the Orient has not just been given it's "intelligibility and identity" by the Occident, but it has also "created the Orient" (p. 40). In Chapter II, Said goes on to present eighteenth century French and English perspectives of Orient by looking at European confrontation with the Orient, particularly by exploring Edward William Lane's Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), which accounts Lane's experiences in Egypt. In his final chapter, Said explores nineteenth and twentieth-century European attitudes toward Islam and Arab culture, both believing in the Orient's ‘latent inferiority' (p. 208) to Western civilisation. At the outset, Said gives three distinct designations to the term Orientalism. Firstly, an academic discipline, ordinarily "Anyone who teaches, writes about, or researches the Orient" (p. 2). Secondly, Said labels Orientalism "as style of thought based upon ontological and epistemological distinction made between ‘the Orient' and ‘the Occident" (p. 2). Lastly, from the late eighteenth-century, Orientalism has been "discussed and analysed as a corporate institution for dealing with the Orient". In other words, dominating and having authority over the Orient. Moreover, Said argues that "because of Orientalism the Orient was not (and is not) a free subject of thought or action." In sum, Said believes Western studies contribute to the West's power thus making power relationships an important part of the thesis (p. 3). Said expounds, claiming this colonial aggrandisement later came to embody "a systemic discipline of accumulation. And far from this being exclusively an intellectual or theoretical feature, it made Orientalism fatally tend towards the systematic accumulation of human beings and 1 territories." Said's thesis is clear: the fundamental nature of Orientalism is the ineffaceable distinction between Occidental superiority and Oriental inferiority. Such distinction grants the explicable convergence between Orientalism and Imperialism, ultimately culminating in the Western colonial rule. Despite criticising Orientalists for failing to be intellectually objective, Said has fallen victim to the fallacy of historiographical Whiggism or reading present values onto past ages. Presenting the past as an inevitable progression toward decolonisation and the expansion of liberal democracy, Said criticises early twentieth-century proponents of imperialism for not fully envisioning decolonisation (p. 39), including Arthur Balfour and Lord Cromer. Aware of the collapse of the British Empire after the Second World War, Said projects his values onto such individuals and seemingly searches for an antiimperialist and anti-Orientalist within history. Furthermore, Said's application of the word Orientalism also draws attention to his frequent substitution of imperialism for the term Orientalism, even going as far as racism, "Every European, in what he could say about the Orient... was a racist, an imperialist, and almost totally ethnocentric (p. 204). Orientalism transforms from being a critical approach to representations of the 'Orient' to a flexible term which is applied to cultural imperialism imposed upon the 'Orient'. To suit Orientalism's polemical purposes, Said manipulates historical evidence in numerous ways. Said firstly chooses to focus only on scholars from the major imperial powers who had colonised the ‘Orient', Britain, France and later America (pp. 15-19) despite the fact German and Hungarian Orientalists dominated Oriental studies in the 19th century with some such as Goldziher being notably anti-imperialist. Curiously, Said readily admitted in the introduction that Germany and Hungary did not fit the "Orientalist Pattern" (p. 20) due to its lack of imperial history in the ‘Orient'. Thus, Said deprives himself of potential sources from Orientalists who would have perhaps challenged his thesis. However, such scholars would have likely weakened his argument and detracted from his hypothesis. Moreover, Said mostly restricts his analysis to the Middle East and overlooks European approaches to former Western colonies such as India and China. There is an issue of reductionism as Said, therefore, implies that they did not differ to Arabs in the Middle East. As a public intellectual, Said was perhaps more interested in putting forth political arguments and reaching a polemical conclusion than practising 2 scholarly rigour. On the other hand, as a Palestinian and supporter of Yasir Arafat's Palestine Liberation Organisation, Said himself was associated politically with the struggle of Arab and Palestinian nationalism, an important aspect of Orientalism. Evidently, Israel and the domination of Arabs and Palestinians was of high political interest to Said. The exclusion of German and Hungarian scholarship and significant parts of the ‘Orient' increases the applicability of Said's thesis and fits his preconceived political agenda. Similarly, Said claims Western knowledge is implicated in Orientalist representations of the 'Other' with the genealogy of Orientalism being rooted in classical Greek thought and eighteenthcentury European ideas. This transhistorical argument clearly suggests that there is a homogeneous Western discourse. Said thus makes compounding deductions of representations about a long span of history in a short book. It is apparent Said has tailored his argument to fit his pre-conceived political agenda to assert Western discourse has remained unchanged for over two thousand years. Consequently, Said makes a generalising sweep of history but fails to address individual episodes. Said's political agenda is perhaps why Orientalism is wrought with such instances of ahistoricism, particularly evident with the methodological issue of his duplicitous approach to historical sources. This method often manifests with the cherry-picking of evidence. Although Said often makes use of primary sources, he frequently omits words and often refutes the intended implication of a source. For instance, Said manipulates quotes from Edward William Lane's Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptions (1836) to frame his work as denigrating the ‘Orient’. By not directly quoting Lane, Said often misconstructs his work and unfairly represents him as a “racist” and “privileged European” (p. 161), the latter an ad hominem response. Said's manipulation of evidence creates a dramatic effect but ultimately invalidates the argument. Nevertheless, one of the few commendable qualities of Orientalism is its readability. Although Said's style can be turgid at times, it does, for the most part, boast clarity and lucidity, therefore, making it accessible to the general public and not only academics. Conversely, Orientalism demonstrates a limited use for historians by not taking the approach of historicism. As a professor of literature and an author dedicated to literary criticism, it is unsurprising Said does not approach 3 Orientalism as historical research. Reviving the debate of Orientalism as both a concept and construct, Said often approaches it as a discourse of power and as a "fictional reality" that has been configured by the West to dominate the East (p. 54). Approaching orientalism in this way, Said has extended the historical debate. However, Said does make it clear that it is not the history of ideas that interests him but the literary-rhetorical aspects of the discourse. Said, therefore, argues the "things to look at [in literature] are style, figures of speech, setting, narrative devices, historical and social circumstances, not the correctness of the representation nor its fidelity to some great original." In sum, Said is mostly interested in "the internal consistency of Orientalism and its ideas about the Orient…despite or beyond any correspondence, or lack thereof, with a "‘real' Orient'" (p. 48). Refusing to make references to Arab literature on Orientalism, the Middle East does not have a voice in the construction of their identity. Said only focuses on the selected Western works by authors such as Giambattista Vico and Antonio Gramsci. The partiality for Western sources combined with an attempt to undertake an extensive period of history thus misleads the reader with the sources Said has used. While Edward Said does offer an excellent insight into the discourse of Orientalism and makes intellectual connections with literature, there are a plethora of profound methodological flaws that renders Orientalism mostly unsuitable for educational purposes and ultimately detracts from the book's central thesis. Moreover, it is evident that Said constructed his overall argument with an anti-Western agenda arrived at by mostly approaching Orientalism as a discourse of power therefore making Orientalism more appropriate for a student of literature or linguistics. On the other hand, it would be unfair not to praise Said's book for drawing the reader's attention to the "Western approach to the Orient". The problem with Western scholarship remains especially relevant as the maxims and acumens of Said's analysis still manifest in the contemporary outlook toward Islam and the Arab ‘Other', making it appropriate for the general public. 4

![Orientalism PPT[1].](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009508903_1-bf40dd03912d19b9c9baea1f12c90f25-300x300.png)